Hydro-Québec: Difference between revisions

Reverted 1 edit by 68.61.114.236; POV — 2nd time. (TW) |

|||

| Line 33: | Line 33: | ||

[[File:MLH & P - monteurs de ligne.jpg|thumb|left|''Montreal Light, Heat and Power'' linesmen.]] |

[[File:MLH & P - monteurs de ligne.jpg|thumb|left|''Montreal Light, Heat and Power'' linesmen.]] |

||

In the fall of 1943, the Godbout government [[bill (proposed law)| |

In the fall of 1943, the Godbout government [[bill (proposed law)|tabled a bill]] to take control of MLH&P, the company running the gas and electric distribution in and around [[Montreal]], Quebec's largest city. On April 14, 1944, the [[National Assembly of Quebec|Quebec Legislative Assembly]] passed Bill 17, creating a publicly-owned commercial venture, the ''Quebec Hydroelectric Commission'', commonly referred to as ''Hydro-Québec''. The [[Statute|act]] granted the new Crown corporation an electric and [[gas distribution]] [[government monopoly|monopoly]] in the Montreal area and mandated Hydro-Québec to serve its customers "at the lowest rates consistent with a sound financial management", to restore the substandard electric grid and to speed up [[rural electrification]] in areas with no or limited electric service.<ref name="Gallichan"/><ref name="Siecle">{{cite book|last=Hogue |first=Clarence |last2=Bolduc |first2=André |last3=Larouche |first3=Daniel |title=Québec : un siècle d'électricité |location=Montreal |publisher=Libre Expression |year=1979 |pages=405 |isbn=2-89111-022-6}}</ref> |

||

MLH&P was [[takeover|taken over]] the next day, April 15, 1944. The new [[management]] quickly realized that it would need to rapidly increase the company's 600-megawatt generation capacity in the next few years in order to meet growing demand. By 1948, Hydro-Québec had started the expansion of the Beauharnois power station.<ref>{{cite book|publisher=Presses de l'Université du Québec |chapter=Cinquante ans au service du consommateur |title=Hydro-Québec : Autres temps, autres défis |first=Robert A. |last=Boyd |authorlink=Robert A. Boyd |language=French |city=Sainte-Foy, Quebec|year=1995|isbn=2-7605-0809-9|pages=97-103}}</ref> It then set its eyes on the [[Betsiamites River|Bersimis]] near [[Forestville]], on the [[Côte-Nord|North Shore]] of the [[Saint Lawrence River]], located {{convert|700|km|mi}} east of Montreal. The Bersimis-1 and Bersimis-2 generating stations were built between 1953 and 1959 and were widely considered to be a [[bench trial]] for the fledgling company. They also offered a preview of the large developments that occurred over the next three decades in Northern Quebec.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.histoiresoubliees.ca/article/labrieville-le-grand-defi/les-barrages-de-la-riviere-bersimis |title=Les barrages de la rivière Bersimis |author=Productions Vic Pelletier |accessdate=2009-03-15 |language=French}}</ref>. |

MLH&P was [[takeover|taken over]] the next day, April 15, 1944. The new [[management]] quickly realized that it would need to rapidly increase the company's 600-megawatt generation capacity in the next few years in order to meet growing demand. By 1948, Hydro-Québec had started the expansion of the Beauharnois power station.<ref>{{cite book|publisher=Presses de l'Université du Québec |chapter=Cinquante ans au service du consommateur |title=Hydro-Québec : Autres temps, autres défis |first=Robert A. |last=Boyd |authorlink=Robert A. Boyd |language=French |city=Sainte-Foy, Quebec|year=1995|isbn=2-7605-0809-9|pages=97-103}}</ref> It then set its eyes on the [[Betsiamites River|Bersimis]] near [[Forestville]], on the [[Côte-Nord|North Shore]] of the [[Saint Lawrence River]], located {{convert|700|km|mi}} east of Montreal. The Bersimis-1 and Bersimis-2 generating stations were built between 1953 and 1959 and were widely considered to be a [[bench trial]] for the fledgling company. They also offered a preview of the large developments that occurred over the next three decades in Northern Quebec.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.histoiresoubliees.ca/article/labrieville-le-grand-defi/les-barrages-de-la-riviere-bersimis |title=Les barrages de la rivière Bersimis |author=Productions Vic Pelletier |accessdate=2009-03-15 |language=French}}</ref>. |

||

Revision as of 13:53, 21 July 2009

| File:Hydro-Québec Logo.svg | |

| Company type | Crown corporation |

|---|---|

| Industry | Electricity generation, transmission and distribution |

| Founded | April 14, 1944 |

| Headquarters | , |

Area served | Quebec |

Key people | Thierry Vandal, President & CEO[1] |

| Services | Electricity |

| Revenue | C$12.72 billion (2008) |

| C$5.46 billion (2008) | |

| C$3.14 billion (2008) | |

| Total assets | C$66.77 billion (2008)[2] |

| Total equity | C$22.06 billion (2008)[2] |

| Owner | Government of Quebec |

Number of employees | 23,345 (2008)[2] |

| Website | www.hydroquebec.com |

Hydro-Québec is a government-owned public utility established in 1944 by the Government of Quebec. The company is in charge of the generation, transmission and distribution of electricity across Quebec. Its head office is located in Montreal.

With fifty-nine hydroelectric and one nuclear generating stations, Hydro-Québec is the largest electricity generator in Canada and the world's largest hydroelectric generating company.[3] The combined capacity of its power stations was 36,429 megawatts in 2008.

History

In the years after the Great Depression, voices were raised in Quebec asking for a government takeover in the electricity business. Many of the criticisms leveled at the so-called "electricity trust" focused on high rates and excessive profits. Inspired by the example of Adam Beck, who had nationalized much of the electric sector in Ontario 20 years earlier, local politicians, such as Philippe Hamel and Télesphore-Damien Bouchard, strongly advocated moving Quebec towards a similar system. Soon after being elected Premier of Quebec in 1939, Adélard Godbout warmed to the concept of a state-owned utility. Godbout was outraged by the inefficient power system dominated by Anglo-Canadian economic interests and the collusion between the Montreal Light, Heat & Power (MLH&P) and the Shawinigan Water & Power Company, the two main companies involved. At one point, he even called the duopoly an "economic dictatorship, crooked and vicious".[4]

The two-step takeover

In the fall of 1943, the Godbout government tabled a bill to take control of MLH&P, the company running the gas and electric distribution in and around Montreal, Quebec's largest city. On April 14, 1944, the Quebec Legislative Assembly passed Bill 17, creating a publicly-owned commercial venture, the Quebec Hydroelectric Commission, commonly referred to as Hydro-Québec. The act granted the new Crown corporation an electric and gas distribution monopoly in the Montreal area and mandated Hydro-Québec to serve its customers "at the lowest rates consistent with a sound financial management", to restore the substandard electric grid and to speed up rural electrification in areas with no or limited electric service.[4][5]

MLH&P was taken over the next day, April 15, 1944. The new management quickly realized that it would need to rapidly increase the company's 600-megawatt generation capacity in the next few years in order to meet growing demand. By 1948, Hydro-Québec had started the expansion of the Beauharnois power station.[6] It then set its eyes on the Bersimis near Forestville, on the North Shore of the Saint Lawrence River, located 700 kilometres (430 mi) east of Montreal. The Bersimis-1 and Bersimis-2 generating stations were built between 1953 and 1959 and were widely considered to be a bench trial for the fledgling company. They also offered a preview of the large developments that occurred over the next three decades in Northern Quebec.[7].

Other construction projects started in the Maurice Duplessis era included a second upgrade of the Beauharnois project and the construction of the Carillon generating station on the Ottawa River.[5] Between 1944 and 1962, Hydro-Québec's installed capacity increased six-fold, from 616 to 3,661 megawatts.[8]

The onset of the Quiet Revolution in 1960 did not stop the construction of new dams. On the contrary, it brought a new momentum to the company's development under the tutelage of a young and energetic Hydraulic Resources minister. René Lévesque, a 38-year-old former television reporter and a bona fide star of the new Lesage government, was appointed to the Hydro-Québec portfolio as part of the liberal Premier's "équipe du tonnerre" (English: "Dream Team"). Lévesque quickly approved continuation of the ongoing construction work and put together a team to nationalize the 11 remaining private companies that still controlled a substantial share of the electricity generation and distribution business in Quebec.

On February 12, 1962, Lévesque started his public campaign for nationalization. In a speech to the Quebec Electric Industry Association he bluntly called the whole electric business an "unbelievably costly mess".[9] The minister then toured the province in order to reassure the population and refute the arguments of the Shawinigan Water & Power Company, the main opponent of the proposed takeover.[5] On September 4 and 5, 1962, Lévesque finally convinced his liberal cabinet colleagues to go ahead with the plan during a working retreat at a fishing camp north of Quebec City. The issue topped the liberal agenda during a snap election called two years early, and their chosen theme, "Maîtres chez nous" (in English: "Master in our Own Homes"), had a strong nationalist undertone.[10]

The Lesage government was reelected on November 14, 1962 and Lévesque went ahead with the plan. On Friday, December 28, 1962 at 6 pm, Hydro-Québec launched an hostile takeover, offering to buy all of the stock in 11 companies at a set price, that was slightly above market value. After hedging their bets for a few weeks, management of the firms advised their shareholders to accept the C$604 million government offer.[11] In addition to buying the 11 companies, most electric co-operatives and municipally-owned utilities were also taken over and merged with the existing Hydro-Québec operations, which became the largest electric company in Quebec on May 1, 1963.[5]

The 1960s and 1970s

Following the 1963 nationalization Hydro-Québec had to deal with three problems simultaneously. It first had to reorganize in order to seamlessly merge the new subsidiaries into the existing structure, while standardizing dozens of networks in various state of disrepair and upgrading large parts of the Abitibi system from 25 to 60 Hz.[12][5]

All of this had to be done while construction of the Manic-Outardes Complex was underway on the North Shore. By 1959, thousands of workers were building 7 new hydroelectric stations, including the 1,314-metre (4,311 ft) wide Daniel Johnson dam, the largest of its kind in the world. Construction on the Manicouagan and Outardes rivers was completed in 1978 with the inauguration of the Outardes-2 generating station.

These large projects raised a new problem that occupied company engineers for a few years: the transmission of the large amounts of power produced by generating stations located hundreds of kilometres away from the urban centers in southern Quebec in an economical fashion. A young engineer named Jean-Jacques Archambault drafted a plan to build 735 kV power lines, a much higher voltage than what was used at the time. Archambault persisted and managed to convince his colleagues and major equipment suppliers of the viability of his plan. The first 735 kV power line was put into commercial service on November 29, 1965.[13][14]

When it bought the Shawinigan Water & Power Company, Hydro-Québec acquired a 20% share of a planned hydroelectric facility at Hamilton Falls[note 1] in Labrador, a project led by a consortium of banks and industrialists, the British Newfoundland Corporation Limited (Brinco). After years of hard bargaining, the parties reached a deal on May 12, 1969 to finance the construction of the power plant. The agreement committed Hydro-Québec to buy most of the plant's output at one-quarter of a cent per kilowatt-hour for 65 years, and to enter into a risk-sharing agreement. Hydro-Québec would cover part of the interest risk and buy some of Brinco's debt, in exchange for a 34.2% share in the company owning the plant, the Churchill Falls (Labrador) Corporation Limited.[2] The 5,428-megawatt Churchill Falls generating station delivered its first kilowatts on December 6, 1971.[15] Its 11 turbines were fully operational by June 1974.

In the aftermath of the 1973 oil crisis, the Newfoundland government, unhappy with the terms of the agreement, bought all of the shares in the Churchill Falls company that were not held by Hydro-Québec. The Newfoundland government then asked to reopen the contract, a demand refused by Hydro-Québec. After a protracted legal battle between the two neighboring provinces, the contract's validity was twice affirmed by the Supreme Court of Canada, in 1984 and 1988.[16][17]

"The Project of the Century"

Almost a year to the day after his April 1970 election, Quebec Premier Robert Bourassa launched a project which he hoped would help him fulfill a campaign promise to create 100,000 new jobs. On April 30, 1971, in front of a gathering of loyal liberal supporters, he announced plans for the construction of a 10,000-megawatt hydroelectric complex in the James Bay area. After assessing three possible options, Hydro-Québec and the government chose to build three new dams on La Grande River, named LG-2, LG-3 and LG-4.

On top of the technical and logistical challenges posed by a public works project of this scope in a harsh and remote setting, the man in charge, Société d'énergie de la Baie James president Robert A. Boyd, had to face the opposition of the 5,000 Cree residents of the area, who had grave concerns about the project's impact on their traditional lifestyle. In November 1973, the Crees got a preliminary injunction that temporarily stopped the construction of the basic infrastructure needed to build the dams, forcing the Bourassa government to negotiate with them.[19]

After a year of difficult negotiations, the Quebec and Canadian governments, Hydro-Québec, the Société d'énergie de la Baie James and the Grand Council of the Crees signed the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement on November 11, 1975. The agreement granted the Crees financial compensation and the management of health and education services in their communities in exchange for the continuation of the project.

Between 14,000 and 18,000 tradesmen were employed on various James Bay construction sites in the period stretching from 1977 to 1981.[20] Inaugurated on October 27, 1979, the LG-2 generating station, an underground powerhouse with a peak capacity of 5,616 megawatts is the most powerful of its kind in the world. The station, the dam and the associated reservoir were renamed in honor of Premier Bourassa a few weeks after his death in 1996.[21] The construction of the first phase of the project was completed with the commissioning of LG-3 in June 1982 and of LG-4 in 1984.[22][23] A second phase of the project was built between 1987 and 1996, adding five more power plants to the complex.

The 1980s and 1990s

After two consecutive decades of sustained growth, the late 1980s and the 1990s were much more difficult for Hydro-Québec, especially on the environmental front. A new hydroelectric development and the construction of a direct current high voltage line built to export power to New England faced strong opposition from the Crees as well as environmental groups from the US and Canada.

In order to export power from the James Bay Project to New England, Hydro-Québec planned the construction of a 1,200-kilometre (750 mi) long direct current power line, with a capacity of 2,000 megawatts, the so-called "Réseau multiterminal à courant continu" (English: Direct Current Multiterminal Network). Construction work on the line went without a problem except at the location where the power line had to cross the Saint Lawrence River, between Grondines and Lotbinière.[24]

Facing strong opposition from local residents to other options, Hydro-Québec built a 4-kilometre (2.5 mi) tunnel under the river, at a cost of C$144 millions,[25] which delayed the project completion by two and a half years. The line was finally commissioned on November 1, 1992.[26][24]

Hydro-Québec and the Bourassa government had a much harder time circumventing the next hurdle in northern Quebec. Robert Bourassa was reelected in late 1985 after a 9-year hiatus. Shortly after taking office he announced yet another hydro development in the James Bay area. The C$12.6 billion Great Whale Project involved the construction of three new generating stations with a combined capacity of 3,160 megawatts. It was to produce 16.3 terawatt-hours of energy each year by the time it was completed in 1998–1999.[27]

The plan immediately proved controversial. As they had in 1973, the Cree people opposed the project and filed lawsuits against Hydro-Québec in Quebec and Canada to prevent its construction, and also took action in many US states to prevent sales of the electricity there.[28][29]

The Crees succeeded in getting the Canadian federal government to establish a parallel environmental assessment process in order to delay construction. Cree leaders also got support from US-based environmental groups and launched a public relation campaign in the US and in Europe, attacking the Great Whale Project, Hydro-Québec and Quebec in general. Launched in the months following the failure of the Meech Lake Accord and the Oka Crisis, the campaign prompted a coalition of Quebec-based environmental groups to dissociate themselves from the Cree campaign.[30][31]

However, the Cree campaign was successful in New York State, where the New York Power Authority canceled a US$5 billion power contract signed with Hydro-Québec in 1990.[32] Two months after the 1994 general election, the new Premier, Jacques Parizeau, announced the suspension of the Great Whale Project, declaring it unnecessary in order to meet Quebec's energy needs.[33]

The moratorium on new hydro projects in northern Quebec after the Great Whale cancellation forced the company's management to develop new sources of electricity to meet increasing demand. In September 2001, Hydro-Québec announced its intention to build a new combined cycle gas turbine plant—the Centrale du Suroît plant—in Beauharnois, southwest of Montreal, stressing the pressing need to secure additional electricity supply to mitigate against any shortfall in the water cycle of its reservoirs.[34] Hydro's rationale also stressed the cost-effectiveness of the plant and the fact that it could be built within a two year period.[35]

The announcement came at a bad time since attention was drawn to the ratification by Canada of the Kyoto Protocol. With estimated emissions levels of 2.25 Mt of carbon dioxide per year, the Suroît plant would have increased the provincial CO2 emissions by nearly 3%.[35] Faced with a public uproar—a poll conducted in January 2004 found that two of every three Quebecers were opposed to it[35]—the Jean Charest government abandoned the project in November 2004.[36]

Battling the elements

During the same period, Hydro-Québec had to deal with three major disruptions to its electric transmission system that were primarily caused by natural disasters. The incidents highlighted a major weakness of Hydro's system: the great distances between the generation facilities and the main markets of southern Quebec.[37]

On April 18, 1988 at 2:05 am, all of Quebec and parts of New England and New Brunswick lost power because of an equipment failure at a critical substation on the North Shore, between Churchill Falls and the Manicouagan area.[38] The blackout, which lasted for up to 8 hours in some areas, was caused by ice deposits on transformation equipment at the Arnaud substation.[39]

Less than a year later, on March 13, 1989 at 2:44 am, a large geomagnetic storm caused variations in the earth's magnetic field, tripping circuit breakers on the transmission network. The James Bay network went off line in less than 90 seconds, giving Quebec its second blackout in 11 months.[40] The power failure lasted 9 hours,[41] and forced Hydro-Québec to implement a program to reduce the risks associated with geomagnetically induced currents.[42]

In January 1998, five consecutive days of heavy freezing rain caused the largest power failure in Hydro-Québec's history. The weight of the ice collapsed 600 kilometres (370 mi) of high voltage power lines and over 3,000 kilometres (1,900 mi) of medium and low voltage distribution lines in southern Quebec. Up to 1.4 million Hydro-Québec customers were forced to live without power for up to five weeks.[43]

Part of the Montérégie region, south of Montreal, was the worst hit area and became known as the Triangle of Darkness (French: Triangle noir) by the media and the population. Ice accumulation exceeded 100 millimetres (4 in) in some locations.[44] Customers on the Island of Montreal and in the Outaouais region were also hit by the power outage, causing significant concerns since many Quebec households use electricity for heating. Hydro-Québec immediately mobilized all crews, including retirees, and asked for the assistance of utility crews from Eastern Canada and the northeastern US. The Canadian Army was also involved in the restoration of power. More than 10,000 workers had to rebuild a significant portion of the network one pylon at a time.[45] At the height of the crisis, on January 9, 1998, the island of Montreal was fed by a single power line. The situation was so dire the Quebec government temporarily resorted to rolling blackouts in downtown Montreal in order to maintain the city's drinking water supply.[45]

Electric service was fully restored on February 7, 1998, 34 days later. The storm cost Hydro-Québec C$725 million in 1998[43] and over C$1 billion was invested in the following decade to strengthen the power grid against similar events.[46] However, part of the operation needed to close the 735 kV loop around Montreal was approved at the height of the crisis without prior environmental impact assessmentand quickly ran into opposition from residents of the Val Saint-François area in the Eastern Townships. The opponents went to court to quash the order-in-council authorizing the power line.[47] Construction work resumed after the National Assembly passed a law[48] retroactively approving the work done in the immediate aftermath of the ice storm, but it also required public hearings on the remaining projects.[47] Construction of the Hertel-Des Cantons high voltage line was properly approved in July 2002 and commissioned a year later.[49]

The 2000s

On February 7, 2002, Premier Bernard Landry and Ted Moses, the head of the Grand Council of the Crees, signed an agreement allowing the construction of new hydroelectric projects in northern Quebec. The Paix des Braves agreement clarified some provisions of the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement, granted a C$4.5 billion compensation to the Cree Nation to be paid over a 50 year period, established a special wildlife and forestry regime, and gave assurances that Cree businesses and workers would get a share of the economic spin offs of future construction projects in the area.[50]

In return, the Cree nation agreed not to challenge new construction projects in the area, such as the Eastmain-1 generating station—authorized by the government in March 1993[51]—and the partial diversion of the Rupert River to the Robert-Bourassa Reservoir, subject to a number of provisions regarding the protection of the natural and social environment.[52]

Construction on the first 480-megawatt plant started in the spring of 2002 with a road linking the project site to the Nemiscau substation 80 kilometres (50 mi) away. In addition to the plant, built on the left bank of the Eastmain River, the project required the construction of a 890-metre (2,920 ft) wide and 70-metre (230 ft) tall dam, 33 smaller dams and a spillway. The three generating units of Eastmain-1 entered into service in the spring of 2007. The plant has an annual output of 2.7 terawatt-hours.[53]

These projects are part of Quebec's 2006–2015 energy strategy. The document called for the development of 4,500 megawatts of new hydroelectric generation, the integration 4,000 megawatts of wind power, increased electricity exports and the implementation of new energy efficiency programs.[54]

Corporate structure and financial results

Corporate structure

Like its counterparts in the North American utility industry, Hydro-Québec was reorganized in the late 1990s to comply with the electricity deregulation in the United States. While still a vertically-integrated company, Hydro-Québec has created separate business units dealing with the generation, transmission and distribution aspects of the business.

The transmission division, TransÉnergie, was the first to be spun-off in 1997, in response to the U.S. Federal Energy Regulatory Commission's publication of Orders 888 and 888A. The restructuring was completed in the year 2000 with the adoption of Bill 116, which amended the Act respecting the Régie de l'énergie (R.S.Q. c. R-6.01),[55] to enact the functional separation of Hydro-Québec's various business units.

This functional separation and the creation of a so-called "heritage pool" (French: volume patrimonial) of electricity echoed a recommendation of a Merrill Lynch study commissioned by the Lucien Bouchard government. The January 2000 study was aimed at finding a way to deregulate the electricity market in a way that was consistent with continental trends while maintaining the "Quebec social pact", namely low, uniform and stable rates across the province, "particularly in the residential sector".[56]

Legislation passed in 2000 forces the generation division, Hydro-Québec Production, to provide the distribution division, Hydro-Québec Distribution, a yearly heritage pool of up to 165 terawatt-hours of energy plus ancillary services—including an extra 13.9 terawatt-hours for losses and a guaranteed peak capacity of 34,342 megawatts[57]—at a set price of 2.79¢ per kilowatt-hour.

Hydro-Québec Distribution has to buy the remainder of the power and energy it needs—approximately 8.2 terawatt-hours in 2007[58]—by calling for tenders for long-term contracts open to all suppliers, including Hydro-Québec Production, or targeted towards suppliers of a particular energy source, like wind or gas power. For instance, Hydro-Québec Distribution launched calls for tenders in 2003 and 2005, for 1,000 and 2,000 megawatts of wind power respectively. Early deliveries started in 2006 and should be completely on-line by December 2015.

The TransÉnergie and distribution divisions remain regulated by the the Régie de l'énergie du Québec (Quebec energy board), an administrative tribunal established to set retail rates for electricity and natural gas for residential, commercial and industrial service in the province based on a cost-of-service approach. The Régie also has extended powers, including approval authority over every transmission and distribution-related capital expenditure project exceeding C$10 million; approval of the terms of service and of long-term supply contracts; dealing with customer complaints; and the setting and enforcement of safety and reliability standards for the electric grid.[59]

The Hydro-Québec Production division is not subject to regulation by the Régie. However, it must still submit every new construction project to a full environmental impact process, including the release of extensive environmental studies. The release of the studies are followed by a public hearing process conducted by the Bureau d'audiences publiques sur l'environnement.

The Société d'énergie de la Baie James (SEBJ) was established in 1971 to build electricity-related infrastructure in the La Grande River area, which supplies approximately half the electricity produced in Quebec. A research institute,[clarification needed] the Institut de recherche d'Hydro-Québec (IREQ) is a world leader in the electric research and development field, since its inception in 1967. IREQ operates facilities in Varennes, on Montreal's South Shore and in Shawinigan, north of Trois-Rivières.[60]

Hydro-Québec employed 23,345 people in 2008,[2] including 2,060 engineers, making the company the largest employer of engineers in Quebec.[61]

Financial results

| 2008 | 2007 | 2006 | 2005 | 2004 | 2003 | 2002 | 2001 | 2000 | 1999 | 1998 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Revenue | 12,717 | 12,330 | 11,161 | 10,887 | 10,341 | 10,197 | 13,002 | 12,578 | 11,429 | 9,608 | 8,879 |

| Net earnings | 3,141 | 2,907 | 3,741 | 2,252 | 2,435 | 1,938 | 1,526 | 1,108 | 1,078 | 906 | 679 |

| Dividends declared | 2,252 | 2,095 | 2,342 | 1,126 | 1,350 | 965 | 763 | 554 | 539 | 453 | 279 |

| Total assets | 66,774 | 64,852 | 63,254 | 60,431 | 58,072 | 57,823 | 59,078 | 59,861 | 59,038 | 56,808 | 57,336 |

| Long-term debt | 36,415 | 34,534 | 34,427 | 33,007 | 33,401 | 35,550 | 36,699 | 37,269 | 34,965 | 36,016 | 37,833 |

For the year ending on December 31, 2008, Hydro-Québec posted net earnings of C$3.141 billion, up 8.0% over the previous year and the best results in the company's 65-year history.[2] Revenue rose by 3.4% in 2008 to C$12.717 billion, while expenditures amounted to C$7.26 billion, up by C$326 million from 2007, with most of it—C$285 million—due to a water royalties increase charged to Hydro-Québec Production by the government.[2]

The company has assets of C$66.774 billion, $C54.987 billion of which are tangible assets. Its long-term debt stood at C$36.415 billion, and the company reported a capitalization rate of 37.7% in 2008. Bonds issued by Hydro-Québec are backed by the Quebec government. On December 31, 2008, long-term securities of Hydro-Québec were rated Aa2 stable by Moody's, AA-positive by Fitch Ratings and A+ by Standard & Poor's.[2]

In 2008, Hydro-Québec paid a $C2.252 billion dividend to its sole shareholder, the Government of Quebec. Between 2004 and 2008, the company paid a total of $C9.2 billion in dividends.[2]

Privatization debate

In 1981 the Parti Québécois government redefined Hydro-Québec's mission by modifying the terms of the social pact of 1944. The government issued itself 43 million shares worth 100 Canadian dollars each, and the amended statute stated that Hydro-Québec would now pay one half of its net earnings in dividends. This amendment to the Hydro-Québec Act started an episodic debate on whether Hydro-Québec should be fully or partially privatized. In recent years, economist Marcel Boyer and businessman Claude Garcia—both associated with the conservative think tank The Montreal Economic Institute—have often raised the issue, claiming that the company could be better managed by the private sector and that the proceeds from a sale would lower public debt.[64][65]

Without going as far as Boyer and Garcia, Mario Dumont, the head of the Action démocratique du Québec, briefly discussed the possibility of selling a minority stake of Hydro-Québec during the 2008 election campaign.[66] Commenting on the issue on Guy A. Lepage's talk show, former PQ Premier Jacques Parizeau estimated that such an idea would be quite unpopular in public opinion, adding that Hydro-Québec is often seen by Quebecers as a national success story and a source of pride.[67] This could explain why various privatization proposals in the past have received little public attention. The liberal government has repeatedly stated that Hydro-Québec is not for sale.[68]

Like many other economists[69][70], Yvan Allaire, from Montreal's Hautes études commerciales business school, advocates increased electricity rates as a way to increase the government's annual dividend without resorting to privatization.[71] Others, like columnist Bertrand Tremblay of Saguenay's Le Quotidien, claim that privatization would signal a drift to the days when Quebec's natural resources were sold in bulk to foreigners at ridiculously low prices. "For too long, Tremblay writes, Quebec was somewhat of a banana republic, almost giving away its forestry and water resources. In turn, those foreign interests were exporting our jobs associated with the development of our natural resources with the complicity of local vultures".[72]

Left-wing academics, such as UQAM's Léo-Paul Lauzon and Gabriel Sainte-Marie, have demonstrated that privatization would be done at the expense of residential customers, who would pay much higher rates. Privatization would also be a betrayal of the social pact between the people and its government. In addition, the province would be short-selling itself by divesting of a choice asset for a minimal short term gain.[73][74]

Activities

Power generation

On December 31, 2008, Hydro-Québec Production owned and operated 58 hydro plants—including 12 of over 1,000 megawatt capacity—and 26 major reservoirs.[2] These facilities are located in 13 of Quebec's 430 watersheds,[75] including the Saint Lawrence, Betsiamites, La Grande, Manicouagan, Ottawa, Outardes, and Saint-Maurice rivers.[76] These plants provide the bulk of electricity generated and sold by the company. Hydro-Québec also reached a tentative agreement on March 13, 2009 to buy the 60% stake owned by AbitibiBowater in the McCormick plant (335 megawatts), located at the mouth of the Manicouagan River near Baie-Comeau, for C$615 million.[77]

Non-hydro plants include the 675-megawatt Gentilly nuclear generating station (a CANDU-design reactor), four thermal plants and an experimental 2-megawatt wind farm, for a total installed capacity of 36,429 megawatts in 2008.[2] The company also buys the bulk of the output of the 5,428-megawatt Churchill Falls generating station in Labrador, under a long term contract expiring in 2041.[2]

| Plant | River | Capacity (MW) |

|---|---|---|

| Robert-Bourassa | La Grande | 5,616 |

| La Grande-4 | La Grande | 2,779 |

| La Grande-3 | La Grande | 2,417 |

| La Grande-2-A | La Grande | 2,106 |

| Beauharnois | Saint Lawrence | 1,903 |

| Manic-5 | Manicouagan | 1,596 |

| La Grande-1 | La Grande | 1,436 |

| Manic-3 | Manicouagan | 1,244 |

| Bersimis-1 | Betsiamites | 1,178 |

| Manic-2 | Manicouagan | 1,123 |

| Manic-5-PA | Manicouagan | 1,064 |

| Outardes-3 | aux Outardes | 1,026 |

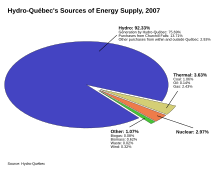

In 2007, the energy supply sold by Hydro-Québec to its customers came primarily from hydroelectric sources (92.33%). Emissions of carbon dioxide (21,390 tonnes/terawatt-hour), sulfur dioxide (74 tonnes/terawatt-hour) and nitrogen oxides (35 tonnes/terawatt-hour) were between 12 and 17 times lower than the industry average in northeastern North America. Imported electricity bought in neighboring markets was responsible for almost all of these emissions.[78]

Transmission network

Hydro-Québec's expertise at building and operating a very high voltage electrical grid spreading over long distances has long been recognized in the electrical industry.[79][80][81] TransÉnergie, Hydro-Québec's transmission division, operates the largest electricity transmission network in North America. It acts as the independent system operator and reliability coordinator for the Québec interconnection of the North American Electric Reliability Corporation system, and is part of the Northeast Power Coordinating Council (NPCC). TransÉnergie manages the flow of energy on the Quebec network and ensures non-discriminatory access to all participants involved in the wholesale market.[82] The non-discriminatory access policy allows a company such as Nalcor to sell some of its share of power from Churchill Falls on the open market in the State of New York using TransÉnergie's network, upon payment of a transmission fee.[83][84]

In recent years, TransÉnergie's Contrôle des mouvements d'énergie (CMÉ) unit has been acting as the reliability coordinator of the bulk electricity network for Quebec as a whole, under a bilateral agreement between the Régie de l'énergie du Québec and the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission of the United States.[85]

TransÉnergie high voltage network stretches over 33,058 kilometres (20,541 mi), including 11,422 kilometres (7,097 mi) of 765 and 735 kV lines,[2] and a network of 510 substations. It is connected to neighboring Canadian provinces and the United States by 18 ties, with a maximum reception capacity of 9,575 megawatts[note 2] and a maximum transmission capacity of 7,100 megawatts.[86]

The TransÉnergie's network operates asynchronously from that of its neighbors on the Eastern Interconnection. Although Quebec uses the same 60 Hz frequency as the rest of North America, the Quebec network does not use the same phase than surrounding networks.[87] TransÉnergie mainly relies on back to back HVDC converters to export or import electricity from other jurisdictions.

This feature of the Quebec network allowed Hydro-Québec to remain unscathed during the Northeast Blackout of August 14, 2003, with the exception of 5 hydro plants on the Ottawa river that are directly connected to the Ontario grid.[88] A new 1250-megawatt back to back HVDC tie is currently under construction at the Outaouais substation, in L'Ange-Gardien, near the Ontario border. The new interconnection and 315 kV line will be fully operational in 2010.[87]

One detail of the TransÉnergie network involves the the long distances between the generation sites and the main consumer markets. For instance, the Radisson substation links the James Bay project plants to Nicolet, south of the Saint Lawrence, over 1,200 kilometres (750 mi) away.[89]

In 2008, TransÉnergie invested C$1.1 billion in capital expenditures, including C$559 million for the expansion of its network.[2] In addition to the new tie with Ontario, the company plans to build a new 1200-megawatt direct current link between the Eastern Townships and New Hampshire. The line would be built in partnership with two US distributors, NSTAR and Northeast Utilities but must first receive regulatory approval in Quebec and the United States. The proposed transmission line could be in operation as early as 2014.[90]

Distribution

The distribution division of Hydro-Québec is in charge of retail sales to customers in Quebec. It operates a network of 110,127 kilometres (68,430 mi) of medium and low voltage lines[2] across the province, with the exception of a dozen municipal distribution networks—in Alma, Amos, Baie-Comeau, Coaticook, Joliette, Magog, Saguenay, Sherbrooke and Westmount—and the electric cooperative of Saint-Jean-Baptiste de Rouville.[91]

Hydro-Québec Distribution buys most of its power from the 165 terawatt-hours heritage pool provided by Hydro-Québec Production at 2.79¢/kilowatt-hour. The division usually purchases additional power by entering into long-term contracts after a public call for tenders. For shorter term needs, it also buys power from the neighboring systems at market prices. As a last resort, Hydro-Québec Production can also provide short-term relief.[62] Supply contracts must be approved by the Régie de l'énergie du Québec and their costs are passed on to customers.

The division signed one natural gas cogeneration agreement for 507 megawatts in 2003, three forest biomass deals (47.5 megawatts) in 2004 and 2005, and ten contracts for wind power (2,994 megawatts) in 2005 and 2008, all with private sector producers. It also signed two flexible contracts with Hydro-Québec Production (600 megawatts) in 2002.[92]

Hydro-Québec Distribution is also responsible for the production of power in remote communities not connected to the main power grid. It operates 23 small diesel power plants and an hydroelectric dam on the Lower North Shore, in the Magdalen Islands, in Haute-Mauricie and in Nunavik.[clarification needed]

Other activities

Construction

The Hydro-Québec Équipement division acts as the company's main contractor on major construction sites, with the exception of work conducted on the territory covered by the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement, which are assigned to the Société d'énergie de la Baie James subsidiary.

After a pause in the 1990s, Hydro-Québec restarted its construction activities in the early years of the 21st century. Recent projects include the Sainte-Marguerite-3 (SM-3) station in 2004 (884 megawatts); Toulnustouc in 2005 (526 megawatts); Eastmain-1 in 2007 (480 megawatts);[93] Peribonka (385 megawatts)[94] and Mercier in 2008 (50.5 megawatts), Rapides-des-Cœurs (76 megawatts) and Chute-Allard (62 megawatts) in 2009.[95]

In the James Bay area, two new plants, Eastmain-1-A (768 megawatts) and Sarcelle (125 megawatts), and the partial diversion of the Rupert River to the Robert-Bourassa Reservoir, are under construction and should be operating at full power by 2011.[96]

The construction of a complex of four hydroelectric projects on the Romaine River (1,550 megawatts) began on May 13, 2009.[97] The plants are scheduled to be built and commissioned between 2014 and 2020.[98]

In his March 2009 inaugural speech, Quebec Premier Jean Charest announced that his government intends to develop the hydroelectric potential of another river on the North Shore, the Petit-Mécatina River.[99]

Research and Development

Since 1967, Hydro-Québec has made significant investments in research and development. In addition to funding university research, the company is the only electric utility in North America to operate a large scale research center, the Institut de recherche d'Hydro-Québec (IREQ) in Varennes, a suburb on the South Shore of Montreal[60]. The research center, established by Lionel Boulet, specializes in the areas of high voltage, mechanics and thermomechanics, network simulations and calibration.[100]

Research conducted by scientists and engineers at IREQ has helped to extend the life of dams, improve water turbine performance, automate network management and increase the transmission capacity of high voltage power lines.[101]

Another research center, the Laboratoire des technologies de l'énergie (LTE) in Shawinigan, was opened in 1988[102] to adapt and develop new products while helping industrial customers improve their energy efficiency.[103]

Hydro-Québec has been criticized for not having taken advantage of some of its innovations. An electric wheel motor concept that struck a chord with Quebecers,[104] first prototyped in 1994 by Pierre Couture, an engineer and physicist working at IREQ, is one of these.[105][106] The heir to the Couture wheel motor is now marketed by TM4, a subsidiary that has made deals with France's Dassault and Heuliez to develop an electric car, the Cleanova, of which prototypes were built in 2006.[107] Hydro-Québec announced in early 2009 at the Montreal International Auto Show that its engine had been chosen by Tata Motors to equip a demonstration version of its Indica model, which will be road tested in Norway.[108][109]

IREQ's researchers are also working on developing new battery technologies for electric cars. Current research is focusing on technologies to increase range, improve performance in cold weather and reduce charging time.[110]

International ventures

Hydro-Québec first forays outside its borders began in 1978. A new subsidiary, Hydro-Québec International, was created to market the company's know-how abroad in the fields of distribution, generation and transmission of electricity. The new venture leveraged the existing pool of expertise in the parent company.

During the next 25 years, Hydro-Québec was particularly active abroad with investments in electricity transmission networks and generation: Transelec in Chile,[111] the Cross Sound Cable in the United States[81], the Consorcio Transmantaro in Peru, Hidroelectrica Rio Lajas in Costa Rica, Murraylink in Australia and the Fortuna generating station in Panamá.[112]

The Crown corporation briefly held a 17% share in SENELEC, Senegal's electric utility, when the Senegalese government decided to sell part of the company to a consortium led by the French company Elyo, a subsidiary of Group Suez Lyonnaise des Eaux, in 1999.[113] The transaction was canceled the following year.[114]

The same year, Hydro-Québec International acquired a 20% stake in the Meiya Power Company in China for C$83 million,[113] which was sold in July 2004.[115] The company's expertise was sought by several hydroelectric developers throughout the world, including the Three Gorges Dam, where Hydro's employees trained Chinese engineers in the fields of management, finance and dams.[116]

Hydro-Québec gradually withdrew from the international business between 2003 and 2006, and sold off all of its foreign investments for a profit. Proceeds from these sales were paid to the government's Generations Fund, a trust fund set up by the province to alleviate the impact of public debt on future generations.[117]

Environment

The construction and operation of electric generation, transmission and distribution facilities has environmental impacts and Hydro-Québec's activities are no exception. Hydroelectric development has an impact on the natural environment where facilities are built and on the people living in the area. For instance, the development of new reservoirs increases the level of mercury in lakes and rivers, which goes up the food chain.[119] It temporarily increases the emission of greenhouse gases from reservoirs[120] and contributes to shoreline erosion.

In addition, hydroelectric facilities transform the human environment. They create new obstacles to navigation, flood traditional hunting and trapping grounds, force people to change their eating habits due to the elevated mercury content of some species of fish, destroy invaluable artifacts that would help trace the human presence on the territory, and disrupt the society and culture of Aboriginal people living near the facilities.

Since the early 1970s, Hydro-Québec has been aware of the environmental externalities of its operations. The adoption of a Quebec statute on environmental quality in 1972, the cancellation of Champigny Project, a planned pumped storage plant in the Jacques-Cartier River valley in 1973, and the James Bay negotiations leading to the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement in 1975, forced the company to reconsider its practices.[121]

To address environmental concerns, Hydro-Québec established a environmental protection committee in 1970 and an Environmental Management unit in September 1973. Its mandate is to study and measure the environmental impacts of the company, prepare impact assessment, and develop mitigation strategies for new and existing facilities, while conducting research projects in these areas, in cooperation with the scientific community.

Impacts on the natural environment

In 1978 the company setup a network of monitoring stations to measure the impacts of the James Bay Project[121] which provide a wealth of data on northern environments. The first 30 years of studies in the James Bay area have confirmed that mercury levels in fish increase by 3 to 6 times over the first 5 to 10 years after the flooding of a reservoir, but then gradually revert to their initial values after 20 to 30 years. These results confirm similar researches conducted elsewhere in Canada, the United States and Finland.[122] Research also found that it is possible to reduce human exposure to mercury even when fish constitutes a significant part of a population's diet. Exposure risks can be mitigated without overly reducing the consumption of fish, simply by avoiding certain species and fishing spots.[122]

Despite the fact that the transformation of a terrestrial environment into an aquatic environment constitutes a major change and that flooding leads to the displacement or death of nonmigratory animals, the riparian environments lost through flooding are partially replaced by new ones on the exposed banks of reduced-flow rivers. The biological diversity of reservoir islands is comparable to other islands in the area and the reservoir drawdown zone is used by a variety of wildlife. The population of migratory species of interest such as the caribou have even increased to the point where the hunt has been expanded.[123]

Emissions of greenhouse gases (GHG) rise significantly for a few years after impoundment, and then stabilize after 10 years to a level similar to that of surrounding lakes.[120] Gross GHG emissions of reservoirs in the James Bay area fluctuate around 30,000 tonnes of CO2 equivalent per terawatt-hour of generated power.[124] Hydro-Québec claims its hydroelectric plant emissions release 35 times less GHG than comparable gas-fired plants and 70 times less than coal-fired ones and that they constitute the "option with the best performance" overall.[120]

Social impacts and sustainable development

Another major environmental concern relates to the population of areas affected by hydroelectric development, specifically the Innu of the North Shore and the Cree and Inuit in Northern Quebec. The hydroelectric developments of the last quarter of the 20th century have accelerated the settling process among Aboriginal populations that started in the 1950s. Among the reasons cited for the increased adoption of a sedentary lifestyle among these peoples are the establishment of Aboriginal businesses, the introduction of paid labor, and the flooding of traditional trapping and fishing lands by the new reservoirs, along with the operation of social and education services run by the communities themselves under the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement.[123]

Some native communities, particularly the Crees, have come to a point "where they increasingly resemble the industrialized society of the South", notes an Hydro-Québec report summarizing the research conducted in the area between 1970 and 2000. The report adds that a similar phenomenon was observed after the construction of roads and hydroelectric plants near isolated communities in northern Canada and Scandinavia. However, growing social problems and rising unemployment have followed the end of the large construction projects in the 1990s. The report concludes that future economic and social development in the area "will largely depend on the desire for cooperation among the various players".[123]

After the strong rejection of the the Suroît project and its subsequent cancellation in November 2004, Hydro-Québec, under the leadership of its new CEO Thierry Vandal, reaffirmed Hydro-Québec's commitment towards energy efficiency, hydropower and development of alternative energy.[125] Since then, Hydro-Québec regularly stresses three criteria for any new hydroelectric development undertaken by the company: projects must be cost effective, environmentally acceptable and well-received by the communities.[62] Hydro-Québec has also taken part in a series of sustainable development initiatives since the late 1980s. Its approach is based on three principles: economic development, social development and environmental protection.[126] Since 2007 the company adheres to the Global Reporting Initiative,[127] which governs the collection and publication of sustainability performance information. The company employs 250 professionals and managers in the environmental field and has implemented an ISO 14001-certified environmental management system.[128]

Rates and customers

Quebec market

| Number of customers |

Sales in Quebec (GWh) |

Revenue (M C$) |

Average annual consumption (kWh) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residential and agricultural | 3,603,330 | 60,747 | 4,300 | 16,974 |

| General and institutional | 296,504 | 25,228 | 2,687 | 118,209 |

| Industrial | 10,111 | 69,144 | 3,174 | 6,379,775 |

| Others | 3,499 | 5,278 | 284 | 1,521,257 |

| Total | 3,913,444 | 170,397 | 10,445 |

At the end of 2008, Hydro-Québec served 3,913,444 customers[2] grouped into three broad categories: residential and farm (D Rate), commercial and institutional (G Rate) and industrial (M and L rates). The Other category includes public lighting systems.

About a dozen distribution rates are set annually by the Régie de l'énergie after public hearings. Pricing is based on the cost of delivery, which includes depreciation on fixed assets and provisions for the maintenance of facilities, customer growth and a profit margin.

Rates are uniform throughout the province and are based on consumer type and volume of consumption. All rates vary in block to mitigate any cross-subsidization effect between residential, commercial and industrial customers.

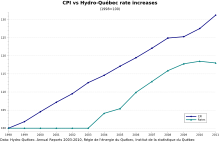

After a five-year rate freeze, between May 1, 1998 and January 1, 2004,[129] the Régie granted 7 rate increases between 2004 and 2009.[130] However, Hydro-Québec rates are still among the lowest in North America.[131]

Residential customers

The average consumption of residential and agricultural customers is relatively high, at 16,974 kilowatt-hours per year, because of the widespread use of electric heating (68% of residences).[132] Hydro-Québec estimates that heating accounts for more than one half of the power used in the residential sector.[133]

This preference for electric heating makes electricity demand more unpredictable, but offers some environmental benefits. Despite Quebec's very cold climate in winter, greenhouse gases emissions in the residential sector accounted for only 5.5% (4.65 Mt eq. CO2) of all emissions in Quebec in 2006. Emissions from the residential sector in Quebec fell by 30% between 1990 and 2006.[134]

Residential use of electricity fluctuates from one year to another, and is strongly correlated with the weather. Contrary to the trend in neighboring networks, Hydro-Québec's system is winter-peaking. A new consumption record was set on January 16, 2009 at 7 am, with a load of 37,220 megawatts.[135] The temperature recorded in Quebec City at the time was −31.8 °C (−25.2 °F).[136] The previous record of 36,268 megawatts was established on January 15, 2004, during another cold spell.[137]

The price of electricity for residential and agricultural customers, in effect since April 1, 2009, includes a 40.64¢ daily subscription fee, and two price levels depending on consumption. Customers pay 5.45¢/kilowatt-hour for the first 30 daily kilowatt-hours, while the extra power is sold at 7.46¢/kilowatt-hour.[138] The average monthly bill for a typical residential customer was approximately C$100 in 2008.[139]

Electric meter readings are usually conducted every two months and bills are bimonthly. However, the company offers an optional Equalized Payment Plan allowing residential customers to pay their annual electricity costs in 12 monthly installments, based on past consumption patterns of the current customer address and the average temperature in that location.[140]

In 2007, Hydro-Québec pulled out of a Canadian government initiative to install smart meters across the province, stating that it would be "too costly to deliver real savings".[141]

Industrial customers

For more than a century, industrial development in Quebec has been stimulated by the abundance of hydraulic resources. Energy represents a significant expenditure in the pulp and paper and aluminum sectors, two industries with long-standing traditions in Quebec. In 2007, industrial customers purchased 69.1 terawatt-hours from Hydro-Québec, representing 40.6% of all electricity sold by the company on the domestic market.[2]

Large industrial users pay a lower rate than the domestic and commercial customers, because of lower distribution costs. In 2008, the largest industrial users, the Rate L customers, were paying an average of 4.57¢/kilowatt-hour.

The Quebec government uses low electricity rates to attract new business and consolidate existing jobs. Despite its statutory obligation to sell electric power to every person who so requests, the province has reserved the right to grant large load allocations to companies on a case by case basis since 1974. The threshold was set at 175 megawatts from 1987 to 2006[142] and was reduced to 50 megawatts in the government's 2006–2015 energy strategy.[54]

In 1987, Hydro-Québec and the Quebec government agreed to a series of controversial deals with aluminum giants Alcan and Alcoa. These so-called "risk sharing" contracts set the price of electricity based on a series of factors, including aluminum world prices and the value of the Canadian dollar[143] Those agreements are gradually being replaced by one based on published rates.

On May 10, 2007, the Quebec government signed an agreement with Alcan. The agreement, which is still in force despite the company's merger with Rio Tinto Group, renews the water rights concession on the Saguenay and Peribonka rivers. In exchange, Alcan has agreed to invest in its Quebec facilities and to maintain jobs and its corporate headquarters in Montreal.[144]

On December 19, 2008, Hydro-Québec and Alcoa signed a similar agreement. This agreement, which expires in 2040, maintains the provision of electricity to Alcoa's three aluminum smelters in the province, located in Baie-Comeau, Bécancour and Deschambault-Grondines. In addition, the deal will allow Alcoa to modernize the Baie-Comeau plant which will increase its production capacity by 110,000 tonnes a year, to a total of 548,000 tonnes.[145]

Several economists, including Université Laval's Jean-Thomas Bernard and Gérard Bélanger, have challenged the government's strategy and argue that sales to large industrial customers are very costly to the Quebec economy. In an article published in 2008 the researchers estimate that, under the current regime, a job in a new aluminum smelter or an expansion project costs the province between C$255,357 and C$729,653 a year, when taking into consideration the money that could be made by selling the excess electricity on the New York market.[146]

This argument is disputed by large industrial customers, who point out that data from 2000 to 2006 indicate that electricity exports prices get lower when quantities increase, and vice versa. "We find that the more we export, the less lucrative it gets", said Luc Boulanger, the head of the association representing Quebec's large industrial customers. In his opinion, the high volatility of electricity markets and the transmission infrastructure physical limitations reduce the quantities of electricity that can be exported when prices are higher.[147]

Export markets

| 2008 | 2007 | 2006 | 2005 | 2004 | 2003 | 2002 | 2001 | 2000 | 1999 | 1998 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exports (GWh)[note 3] | 21,299 | 19,624 | 14,458 | 15,342 | 14,392 | 15,786 | 54,199 | 42,389 | 36,907 | 24,230 | 18,565 |

| Revenue (M C$) | 1,919 | 1,617 | 1,149 | 1,464 | 1,084 | 1,345 | 3,467 | 3,082 | 2,349 | 1,016 | 814 |

Hydro-Québec sells part of its surplus electricity to neighboring systems in Canada and the United States under long term contracts and transactions on the New England, New York and Ontario bulk energy markets. Two subsidiaries, Marketing d'énergie HQ and HQ Energy Services (U.S.) are engaged in the electricity trade on behalf of the company. In 2008, Hydro-Québec exported 21.3 terawatt-hours of electricity, and the brokerage business generated revenues of C$1.9 billion.[2]

Although most export sales are now short-term transactions, Hydro-Québec has signed long-term contracts in the past. In 1990, the company signed a 328-megawatt deal with a group of 13 electric distributors in Vermont. The contract with the Vermont Joint Owners will expire in 2015 and negotiations are underway to renew it.[149] Exports from Hydro-Québec account for 28% of all power used in the state.[150] A second contract has been signed with Cornwall Electric, a subsidiary of Fortis Inc., a utility serving 23,000 customers in the Cornwall, Ontario area. The contract was renewed in 2008 and will be in force until 2019.[151]

The company has several advantages in its dealings in export markets. First, its costs are not affected by the fluctuations of fossil fuel prices, since hydropower require no fuel. Also, Hydro-Québec has a lot of flexibility in matching supply and demand, so it can sell electricity at higher prices during the day and replenish its reservoirs at night, when wholesale prices are lower. Third, the Quebec power grid peaks in winter because of heating, unlike most neighboring systems, where peak demand occur on very warm days in the summer, due to the air conditioning needs of homes and offices.[152]

The election of Barack Obama—a supporter of renewable energy, greenhouse gas emissions trading and the development of electric cars—as president of the United States in 2008 was seen as a positive development for the company's outlook. Despite the success of the current policy of short-term sales on neighboring energy markets, the minister in charge of Hydro-Québec, Claude Béchard, recently asked the company's management to write a new strategic plan that would prioritize long-term sale agreements with US distributors, as was the case after the commissioning of the James Bay Project.[153]

See also

- Édifice Hydro-Québec

- James Bay Project

- Hydro-Québec's electricity transmission system

- Timeline of Quebec history

Footnotes

- ^ The falls were renamed to honor the late British Prime Minister, Sir Winston Churchill, soon after his passing, in 1965.

- ^ This number includes the 5200-megawatt Churchill Falls lines, which have no export capability.

- ^ Numbers include energy brokerage on the markets. This energy has not necessarily been produced by Hydro-Québec's plants.

Notes

- ^ Hydro-Québec (2008). "Hydro-Québec organizational chart" (pdf). Retrieved 2009-05-04.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Hydro-Québec (2009). Powering Our Future : Annual Report 2008 (pdf). Montreal. p. 125. ISBN 978-2-550-55046-4.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Ed Crooks (2009). "Using Russian hydro to power China". Financial Times. Retrieved 2009-07-07.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Gallichan, Gilles. "De la Montreal Light, Heat and Power à Hydro-Québec". Hydro-Québec : Autres temps, autres défis (in French). Sainte-Foy: Presses de l'Université du Québec. pp. 63–70. ISBN 2-7605-0809-9.

- ^ a b c d e Hogue, Clarence; Bolduc, André; Larouche, Daniel (1979). Québec : un siècle d'électricité. Montreal: Libre Expression. p. 405. ISBN 2-89111-022-6.

- ^ Boyd, Robert A. (1995). "Cinquante ans au service du consommateur". Hydro-Québec : Autres temps, autres défis (in French). Presses de l'Université du Québec. pp. 97–103. ISBN 2-7605-0809-9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|city=ignored (|location=suggested) (help) - ^ Productions Vic Pelletier. "Les barrages de la rivière Bersimis" (in French). Retrieved 2009-03-15.

- ^ Jobin, Carol (1978). Les enjeux économiques de la nationalisation de l'électricité (1962-1963) (in French). Montreal: Éditions coopératives Albert Saint-Martin.

- ^ Brassard, Jacques (2000). "Pacte social et modernité réglementaire : des enjeux réconciliables - Allocution de monsieur Jacques Brassard, ministre des Ressources naturelles, à l'occasion du déjeuner conférence de l'Association de l'industrie électrique du Québec" (in French). Retrieved 2009-03-15.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Bélanger, Michel. "Les actions d'Hydo-Québec à vendre ?". Hydro-Québec : Autres temps, autres défis. Sainte-Foy: Presses de l'Université du Québec. pp. 89–95. ISBN 2-7605-0809-9.

- ^ Tremblay, Joël; Gaudreau, Serge. "Bilan du siècle : 28 décembre 1962 - Nationalisation de onze compagnies d'électricité par la Commission hydroélectrique du Québec" (in French). Université de Sherbrooke. Retrieved 2009-03-14.

- ^ Linteau, Paul-André (1993–1994). "Hydro-Québec and Québec society: Fifty years of shared history". Forces. No. 104. pp. 14–17. ISSN 0015-6957.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ Sood, Vijay K. (2006). "IEEE Milestone : 40th Anniversary of 735 kV Transmission System" (pdf). IEEE Canadian Review. pp. 6–7. Retrieved 2009-03-14.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Trinôme Inc. Chantiers : La route des pylônes. Documentary broadcast on the Historia channel. 2006.

- ^ Green, Peter. "The History of Churchill Falls". IEEE Canada. Retrieved 2009-03-16.

- ^ Supreme Court of Canada (1984). "Reference re Upper Churchill Water Rights Reversion Act, (1984) 1 S.C.R. 297". Retrieved 2009-03-14..

- ^ Supreme Court of Canada (1988). "Hydro-Québec v. Churchill Falls (Labrador) Corp., (1988) 1 S.C.R. 1087". Retrieved 2009-03-14..

- ^ Turgeon, Pierre (1992). La Radissonie, le pays de la baie James (in French). Montreal: Libre-Expression. p. 191. ISBN 2-89111-502-3.

- ^ Godin, Pierre (1994). "Robert Bourassa : les mégaprojets. À mille kilomètres de Montréal, arracher des milliards de kilowatts à une région nordique fabuleuse et hostile...". Le Devoir (in French). p. E7.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Société d'Énergie de la Baie James (1987). Le complexe hydroélectrique de La Grande Rivière - Réalisation de la première phase (in French). Montreal: Société d'Énergie de la Baie James / Éditions de la Chenelière. p. 416. ISBN 2-89310-010-4.

- ^ Commission de toponymie du Québec (2009). "Centrale Robert-Bourassa". Topos sur le web (in French). Retrieved 2009-03-22.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Radio-Canada (2007). "La grande aventure de la baie James : Détourner les eaux". Radio-Canada Archives (in French). Retrieved 2008-08-03.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Radio-Canada (2007). "La grande aventure de la baie James : Lancement des premières turbines". Radio-Canada Archives (in French). Retrieved 2008-08-03.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Fleury, Jean Louis (1999). Les coureurs de lignes : l'histoire du transport de l'électricité au Québec (in French). Montreal: Stanké. p. 507. ISBN 2-7604-0552-4.

- ^ Gingras, Pierre (1990). "Sans être spectaculaire, la ligne de Grondines n'en est pas moins unique au monde". La Presse (in French). p. G2.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Presse canadienne (1992). "Grondines : la ligne électrique sous-fluviale est terminée". La Presse (in French). p. H1.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Bernard, Jean-Thomas; Genest-Laplante, Éric; Laplante, Benoit (1992). "Le coût d'abandonner le projet Grande-Baleine" (pdf). Canadian Public Policy (in French). 18 (2): 153–167. Retrieved 2009-03-16.

- ^ Parent, Rollande (1990). "Ventes d'électricité : la contestation des Cris tourne court". La Presse (in French). Canadian Press. p. D9.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Tremblay, Frédéric (1992). "Les Cris perdent la bataille du Vermont". Le Devoir (in French). Canadian Press. p. A5.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Pelchat, Martin (1992). "Hydro et des écologistes québécois dénoncent une organisation américaine". La Presse (in French). p. A5.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Francoeur, Louis-Gilles (1992). "Écologistes québécois et américains ajustent leur tir sur Grande-Baleine". Le Devoir (in French). p. 3.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Presse canadienne. "NYPA annule un contrat important". Le Soleil (in French). p. B8.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|année=ignored (|date=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Francoeur, Louis-Gilles (1994). "Parizeau gèle le projet Grande-Baleine". Le Devoir (in French). p. A1.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Hydro-Québec Production (2004). "Réponses d'Hydro-Québec Production à la demande de renseignements N° 1 de la Régie au Producteur en date du 5 mars 2004 (HQP-3, document 1)" (pdf) (in French). Régie de l'énergie du Québec. p. 51. Retrieved 2009-03-29.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|série=ignored (|series=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Boutin, Vicky (2004). "La saga du Suroît". L'annuaire du Québec 2005 (in French). Montreal: Fides. pp. 554–557. ISBN 2-7621-2568-5.

- ^ "Communiqué c4483: Centrale du Suroît : le gouvernement du Québec retire son autorisation de réaliser le projet" (Press release) (in French). Quebec Department of Natural Resources and Wildlife. 2004. Retrieved 2009-03-21.

{{cite press release}}: Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Munich Re (2003). Failure of Public Utilities : Risk Management and Insurance (pdf). Munich. pp. 6–7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Bisson, Bruno (1988). "Panne d'électricité majeure : le Québec dans le noir". La Presse (in French). p. A1.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Lamon, Georges (1988). "Hydro-Québec : retour à la normale après la panne d'électricité qui aura duré jusqu'à huit heures" (in French). p. A1.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|périodique=ignored (|publisher=suggested) (help) - ^ Morin, Michel; Sirois, Gilles; Derome, Bernard (1989). "Le Québec dans le noir" (in French). Radio-Canada. Retrieved 2009-03-21.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Hydro-Québec. "Electricity in nature - March 1989". Retrieved 2009-03-15.

- ^ Bonhomme, Jean-Pierre (1991). "La tempête géomagnétique n'a pas perturbé le réseau d'Hydro-Québec". La Presse (in French). pp. A18.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Hydro-Québec (1999). Rapport annuel 1998. Pour aujourd'hui et pour demain (in French). Montreal. ISBN 2-550-34164-3 (PDF).

{{cite book}}:|archive-url=requires|archive-date=(help);|format=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Phillips, David (2002). "The worst icestorm in Canadian history?". Environment Canada. Retrieved 2009-03-16.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Lévesque, Kathleen (2008). "Autopsie d'un cauchemar de glace". Le Devoir (in French). Retrieved 2009-03-16.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Turcotte, Claude (2008). "L'après-crise aura coûté deux milliards". Le Devoir (in French). Retrieved 2009-03-16.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Bureau d'audiences publiques sur l'environnement (2000). Rapport 144. Ligne à 735 kV Saint-Césaire–Hertel et poste de la Montérégie (pdf) (in French). Quebec City. p. 111. ISBN 2-550-36846-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ National Assembly of Quebec (1999). "Loi concernant la construction par Hydro-Québec d'infrastructures et d'équipements par suite de la tempête de verglas survenue du 5 au 9 janvier 1998". Projet de loi no 42 (1999, chapitre 27) (pdf) (in French). Quebec City: Éditeur officiel du Québec. p. 6.

- ^ Radio-Canada (1998). "Non à la ligne Hertel Des Cantons". Radio-Canada Archives (in French). Retrieved 2009-03-23.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Radio-Canada (2002). "La paix des braves est signée" (in French). Retrieved 2009-03-15.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Hydro-Québec. "Eastmain-1 Hydroelectric Development - See the Schedule" (in French). Retrieved 2009-03-15.

- ^ Hydro-Québec. "Eastmain-1-A-Sarcelle-Rupert Project - Partnership with the Crees". Retrieved 2009-03-17.

- ^ Hydro-Québec. "Eastmain-1 Hydroelectric Project. Read a Summary". Retrieved 2009-03-17.

- ^ a b Gouvernement of Quebec (2006). Using energy to build the Québec of tomorrow (pdf). Quebec City: Quebec Department of Natural Ressources and Wildlife. ISBN 2-550-46952-6..

- ^ National Assembly of Quebec. "An Act respecting the Régie de l'énergie, R.S.Q. c. R-6.01". Retrieved 2009-03-14.

- ^ Trabandt, Charles A. (2000). Le tarif de fourniture d'électricité au Québec et les options possibles pour introduire la concurrence dans la production d'électricité (in French). New York: Merrill Lynch. p. 114.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Hydro-Québec Distribution (2008). "Respect du critère de fiabilité en puissance - bilan du Distributeur pour l'année 2008-2009" (pdf). Régie de l'énergie du Québec. p. 12. Retrieved 2009-03-27.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Hydro-Québec Distribution (2008). "Approvisionnements — Demande R-3677-2008 à la Régie de l'énergie du Québec, document HQD-2, document 2" (pdf) (in French). Retrieved 2009-03-19.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Régie de l'énergie du Québec (2008). 2007-2008 Annual Report. Montréal. p. 4. ISBN 978-2-550-53010-7.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Gauthier, Johanne (2007). "L'IREQ : leader de l'innovation technologique à Hydro-Québec" (pdf). Choc (in French). Vol. 25, no. 2. pp. 26–29. Retrieved 2009-03-20.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Morazain, Jeanne (2008). "Top 45 - Hydro-Québec". Plan - La revue de l'Ordre des Ingénieurs du Québec (in French). p. 14. ISSN 0032-0536.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d Hydro-Québec (2008). 2007 Annual Report : Green Energy (pdf). Montreal. p. 124. ISBN 978-2-550-52014-6.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Hydro-Québec (2003). Rapport annuel 2002. Les grands métiers de l'électricité (in French). Montreal. p. 115. ISBN 2-550-40535-8 (PDF).

{{cite book}}:|archive-url=requires|archive-date=(help);|format=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Boyer, Marcel; Garcia, Claude (2007). "Privatising Hydro-Québec : An idea worth exploring" (pdf). Montreal Economic Institute. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Garcia, Claude (2009). "How would the privatisation of Hydro-Québec would make Quebecers richer ?" (pdf). Montreal Economic Institute. ISBN 2-922687-25-2. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Radio-Canada (2008). "Faut-il privatiser Hydro ?". Québec 2008 (in French). Retrieved 2009-03-18.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Lepage, Guy A. (2008). "Tout le monde en parle (interview)". Radio-Canada. Retrieved 2009-04-11.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Lessard, Denis (2009). "Privatisation d'Hydro : « pas dans les cartons du gouvernement »". La Presse (in French). Retrieved 2009-03-19.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Fortin, Pierre (2008). "Vive l'électricité plus chère !". L'actualité (in French). Retrieved 2009-03-31.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Le marché québécois de l'électricité : à la croisée des chemins" (PDF). Groupe de recherche en économie de l'énergie, de l'environnement et des ressources naturelles (GREEN). Université Laval. 2005. p. 17. Retrieved 2009-04-11.

{{cite web}}:|first=missing|last=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|name=ignored (help) - ^ Allaire, Yvan (2007). "Privatiser Hydro-Québec ?". Le Devoir (in French). Retrieved 2009-03-18.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Tremblay, Bertrand (2009). "Non à la privatisation". Le Quotidien (in French). Retrieved 2009-03-31.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Lauzon, Léo Paul (1994). "Continuer à privatiser Hydro-Québec, ou consolider ses opérations" (pdf). Retrieved 2009-03-18.

- ^ Sainte-Marie, Gabriel (2009). "Vendre Hydro ne règle rien". Le Soleil (in French). Retrieved 2009-03-18.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Government of Quebec (2002). Water. Our Life. Our Future. Quebec Water Policy (pdf). Quebec City: Quebec Department of Sustainable Development, the Environment and Parks. ISBN 2-550-40076-3..

- ^ Hydro-Québec. "Discover our Hydroelectric Facilities". Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- ^ Turcotte, Claude (2009). "AbitibiBowater annonce un plan de recapitalisation - La forestière vend à Hydro-Québec la centrale Manicouagan". Le Devoir (in French). Retrieved 2009-03-14.