Black Saturday bushfires: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 124.176.108.138 (talk) to last version by Bidgee |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Infobox wildfire |

{{Infobox wildfire |

||

|title= Black Saturday bushfires<!--This must be the same name as |

|title= Black Saturday bushfires<!--This must be the same name as t hello my name is mini he article. Do not change unless the article is moved.--> |

||

|image= February 7 Victoria Bushfires - MODIS Aqua.jpg |

|image= February 7 Victoria Bushfires - MODIS Aqua.jpg |

||

|caption= [[w:Moderate-Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer|MODIS]] [[w:Aqua (satellite)|Aqua]] satellite image of smoke and [[pyrocumulus cloud]] northeast of [[Melbourne]] during the afternoon of 7 February.<ref>{{cite news |last=Gorman |first=Paul |title=Heat wave fails to arrive |work=[[The Press]] |publisher=Fairfax New Zealand |date=9 February 2009 |url=http://www.stuff.co.nz/stuff/thepress/4841601a6009.html |accessdate=9 February 2009}}</ref> |

|caption= [[w:Moderate-Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer|MODIS]] [[w:Aqua (satellite)|Aqua]] satellite image of smoke and [[pyrocumulus cloud]] northeast of [[Melbourne]] during the afternoon of 7 February.<ref>{{cite news |last=Gorman |first=Paul |title=Heat wave fails to arrive |work=[[The Press]] |publisher=Fairfax New Zealand |date=9 February 2009 |url=http://www.stuff.co.nz/stuff/thepress/4841601a6009.html |accessdate=9 February 2009}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 04:47, 22 March 2010

| Black Saturday bushfires | |

|---|---|

MODIS Aqua satellite image of smoke and pyrocumulus cloud northeast of Melbourne during the afternoon of 7 February.[1] | |

| Date(s) | 7 February – 14 March 2009 |

| Location | Victoria, Australia |

| Statistics | |

| Burned area | Over 4,500 km² (450,000 hectares, 1.1 million acres)[2] |

| Land use | Urban/Rural Fringe Areas, Farmland, and Forest Reserves/National Parks |

| Impacts | |

| Deaths | 173[3][4] |

| Non-fatal injuries | 414[5] |

The Black Saturday bushfires,[11] were a series of bushfires that ignited or were burning across the Australian state of Victoria on and around Saturday 7 February 2009 during extreme bushfire-weather conditions, resulting in Australia's highest ever loss of life from a bushfire.[12] 173 people died as a result of the fires[3][13] and 414 were injured.

As many as 400 individual fires were recorded on 7 February. Following the events of 7 February 2009, that date has since been referred to as Black Saturday.

Overview

Conditions

The majority of the fires ignited and spread on a day of some of the worst bushfire-weather conditions ever recorded. Temperatures in the mid to high 40s (°C, approx. 110–120°F) and wind speeds in excess of 100 kilometres per hour (62 mph), precipitated by an intense heat wave, fanned the fires over large distances and areas, creating several large firestorms and pyrocumulus systems, particularly north-east of Melbourne, where a single firestorm accounted for 120 of the 173 deaths. A cool change hit the state in the early evening, bringing with it gale-force south-westerly winds in excess of 120 kilometres per hour (75 mph). This change in wind direction caused the long eastern flanks of the fires to become massive fire fronts that burned with incredible speed and ferocity towards towns that had earlier escaped the fires.

Effects

The fires destroyed over 2,029 houses, 3,500+ structures in total[14] and damaged thousands more. Many towns north-east of the state capital Melbourne were badly damaged or almost completely destroyed, including Kinglake, Marysville, Narbethong, Strathewen and Flowerdale.[15][16] Many houses in the towns of Steels Creek, Humevale, Wandong, St Andrews, Callignee, Taggerty and Koornalla were also destroyed or severely damaged, with several fatalities recorded at each location. The fires affected 78 individual townships in total and displaced an estimated 7,562 people,[14] many of whom sought temporary accommodation, much of it donated in the form of spare rooms, caravans, tents and beds in community relief centres.

Causes

The majority of the fires were ignited by fallen or clashing power lines or were deliberately lit .[7] Other suspected ignition sources include lightning,[8] cigarette butts,[17] and sparks from a power tool.[10] More distantly implicated was a major drought that has persisted for more than a decade, as well as a domestic 50-year warming trend that has been linked to human-induced climate change.[18][19] By early-mid March, favourable conditions aided containment efforts and extinguished the fires.

Background

A week before the fires, an exceptional heat wave affected south-eastern Australia. From 28-30 January, Melbourne broke records by sweltering through three consecutive days above 43 °C (109 °F), with the temperature peaking at 45.1 °C (113.2 °F), the third hottest day in the city's history.

The heatwave was caused by a slow moving high-pressure system that settled over the Tasman Sea, with a combination of an intense tropical low located off the North West Australian coast and a monsoon trough over Northern Australia, which produced ideal conditions for hot tropical air to be directed down over south-eastern Australia.[20]

The February fires commenced on a day when several localities across the state, including Melbourne, recorded their highest temperatures since records began in 1859.[21] On 6 February 2009—the day before the fires started—the Premier of Victoria John Brumby issued a warning about the extreme weather conditions expected on 7 February: "It's just as bad a day as you can imagine and on top of that the state is just tinder-dry. People need to exercise real common sense tomorrow".[22] The Premier went on to state that it was expected to be the "worst day [of fire conditions] in the history of the state".[22]

Events of Saturday 7 February

3582 firefighting personnel were deployed across the state on the morning of 7 February in anticipation of the extreme conditions. By mid-morning, hot northwesterly winds in excess of 100 kilometres per hour (62 mph) hit the state, accompanied by extremely high temperatures and extremely low humidity. Also a total fire ban for the entire state was declared.

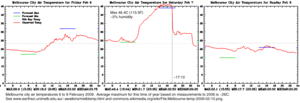

As the day progressed, all-time record temperatures were being reached, 46.4 °C (115.5 °F) in Melbourne, the hottest temperature ever recorded in an Australian capital city[21] and humidity levels dropped to as low as 6%. The McArthur Forest Fire Danger Index reached unprecedented levels, ranging from 120 to over 200. This was higher than the fire weather conditions experienced on Black Friday in 1939 and Ash Wednesday in 1983.[23]

By midday, windspeeds were reaching their peak and by 12:30pm, powerlines were felled in Kilmore East by the high winds, sparking a bushfire that would later generate extensive pyrocumulus cloud and become the largest, deadliest and most intense firestorm ever experienced in Australia's post-European history. The overwhelming majority of fire activity occurred between midday and 7pm, when windspeed and temperature were at their highest and humidity at its lowest.

Chronology

- Wednesday 28 January 2009

- Delburn fire commences in West Gippsland, arson suspected.[24]

- Wednesday 4 February

- Bunyip State Park fire commences.[25]

- Saturday 7 February (Black Saturday)

- Mid morning - Bunyip State Park fire jumps containment lines, no other major fire activity.

- Late morning - Many fires spring up simultaneously as windspeeds increase and temperature rises.

- 11:20am - Powerlines are felled in high winds igniting a fire at Kilmore East (Kinglake/Whittlesea Area). The fire is fanned by 125 kilometres per hour (78 mph)* winds, enters pine plantation, grows in intensity and rapidly heads southeast through the Wandong area.[26]

- 12:30pm - Horsham fire commences.[27]

- Early afternoon - ABC Radio receive calls from residents of affected areas supplying immediate up-to-date information on fire activity.

- 2:55pm - Murrindindi Mill (Marysville Area) fire first spotted from Mt Despair fire tower.[28],[29]

- 3:04pm - Temperature in Melbourne peaks at 46.4 °C (115.5 °F)

- 4:20pm - Kilmore East fire front arrives at Strathewen.[30]

- 4:20pm - Fire impacts Narbethong

- Mid afternoon - Smoke from Kilmore East firestorm prevents planes from mapping the fire edge.

- 4:30pm - Number of individual fires across the state increases into the hundreds.

- 4:30pm - Fire commences at Eaglehawk, near Bendigo[30]

- 4:45pm - Kilmore East fire front arrives at Kinglake.

- 5:00pm - Wind direction changes from northwesterly to southwesterly in Melbourne (see Fawkner Beacon Wind chart for February 7, 2009)

- 5:10pm - Air temperature in Melbourne drops from over 45 to around 30 in 15 minutes.

- 5:30pm - Wind change arrives at Kilmore East and Murrindindi Mill (Kinglake/Marysville) fire fronts.

- 5:45pm - Kilmore East fire front arrives in Flowerdale.

- 6:00pm - Beechworth fire commences.[31]

- 6:00pm - Kilmore East fire (Kinglake area) smoke plume and pyrocumulus cloud reaches 15 km (9.3 mi) high.

- 6:45pm - Murrindindi Mill Fire front arrives at Marysville[32][33]

- 8:30pm - Victorian Health Emergency Co-ordination Centre notifies Melbourne hospitals to prepare for burn victims.

- 8:57pm - CFA chief officer first notified that casualties had been confirmed.

- 10:00pm - Victoria Police announce an initial estimate of 14 fatalities.

- Sunday 8 February

- Kilmore and Murrindindi Mill fires merge to form the Kinglake fire complex.[34]

- Wilsons Promontory fire ignited by lightning.[35]

- Victoria Police increase estimate to 25 fatalities.

- Tuesday 10 February

- Spot fires from Kinglake Complex fires merge to form the Maroondah/Yarra complex.

- Tuesday 17 February

- Six fires still burn out of control with another 19 contained.[36]

- Containment lines surround 85 per cent of the Kinglake-Murrindindi complex.[36]

- The Kilmore East-Murrindindi Complex South fire burns in Melbourne's O'Shannassy and Armstrong Creek water catchments.[36]

- The Bunyip and Beechworth fires close to being contained.[36]

- Thursday 19 February

- Victoria Police increase estimate to 208 fatalities.

- Monday 23 February

- Temperatures in the mid 30s Celsius (mid 90s Fahrenheit), northerly winds and a cool change precipitated a flare up of many of the fires and ignited several new fires, the most major being in the southern Dandenong Ranges near Upwey, south of Daylesford and the Otway Ranges, and directs previously burning fires in the Yarra Ranges towards settlements in the upper Yarra Valley, but the fires are of a low intensity and are quickly contained.

- Friday 27 February

- The Bunyip fire still burning within control lines in the Bunyip State Park and State Forest areas[37]

- The Kilmore East-Murrindindi Complex North fire burns within containment lines on the South Eastern flank.[38]

- The Kilmore East-Murrindindi Complex South Fire activity continues in areas close to several towns in the Yarra Valley and the Warburton Valley.[39]

- The Wilsons Prom Cathedral Fire 24,150 ha (59,700 acres) in size and still burning.[40]

- The French Island fire slowly burning in uninhabited grass and scrub bushland on the North East end of the island.[41]

- Tuesday 3 March 2009

- Extreme bushfire conditions predicted for Monday night and early Tuesday morning, involving very strong northerlies, with a change to arrive by Tuesday morning. Approximately 3 million SMS messages warning of extreme fire danger conditions are sent by the mobile phone companies, on behalf of Victoria Police to Victorians and Tasmanians with mobile phones as a technology trial.[42]

- Wednesday 4 March

- Cooler conditions and rain from the 4-6 March enable firefighters to control and contain several fires; the Kilmore-Murrindindi Complex South being completely contained. Predictions for favourable weather signal the easing of the threat to settlements from the major fires that have been burning since 7 February.

- Mid March

- Favourable conditions aided containment efforts and extinguished many of the fires.

Major fires

Kinglake-Marysville fires

The Kinglake fire complex was named after two earlier fires, the Kilmore East fire and the Murrindindi Mill fire, merged following the wind change on the evening of 7 February.[43] The complex was the largest of the many fires burning on Black Saturday, destroying over 330,000 ha (820,000 acres) [44] It was also the most destructive, with over 1,800 houses destroyed and 159 lives lost in the region.

Kinglake area (Kilmore East fire)

Just before midday on 7 February, high winds felled a 2 km (1.2 mi) section of power lines owned by SP AusNet in Kilmore East, sparking a fire in open grasslands that adjoin pine plantations. The fire was fanned by extreme north-westerly winds, and traveled 50 km (31 mi) south-east in a narrow fire front through Wandong, Clonbinane, into Kinglake National Park and onto the towns of Humevale, Kinglake West, Strathewen and St Andrews.[45]

The cool change passed through the area around 5:30pm, bringing strong south-westerly winds. The wind change turned the initial long and narrow fire band into a wide firefront that moved in a north-east direction through Kinglake, Steels Creek, Chum Creek, Toolangi, Hazeldene and Flowerdale.[46]

The area become the worst impacted in the state, with a total of 120 deaths[3] and more than 1,200 homes destroyed.[47]

Marysville area (Murrindindi Mill fire)

According to eyewitnesses, the Murrindindi Mill fire started at 2:55pm.[48] Victoria Police have twice told the Royal Commission that it commenced at "about 2.30pm".[49],[50] It burned south-east across the Black Range, parallel to the Kilmore fire, towards Narbethong. Experienced Air Attack Coordinator Shaun Lawlor reported flame heights of "at least 100 metres" as the fire traversed the Black Range.[51] At Narbethong, it destroyed 95 per cent of the town's houses[52]. When the southerly change struck, it swept towards the town of Marysville.[53]

Late in the afternoon of 7 February, residents had anticipated that the fire front would bypass Marysville.[53] At about 5:00pm, power was lost to the town. Around 5:30pm, the wind died away; minutes later it returned from a different direction, bringing the fire up the valley with it.[54] A police sergeant said that the main street in Marysville had been destroyed: "The motel at one end of it partially exists. The bakery has survived. Don't ask me how. Everything else is just nuked."[55] Reports on 11 February estimated that around 100 of the town's approximate population of 500 had believed to have perished, and that only "a dozen" buildings were left. Premier Brumby described: "There's no activity, there's no people, there's no buildings, there's no birds, there's no animals, everything's just gone. So the fatality rate will be very high."[56] 34 fatalities were eventually confirmed in the Marysville area, with all but 14 of over 400 buildings destroyed. Other localities severely affected included Buxton and Taggerty.[57]

To the south of the fire complex, visitors and residents were stranded at Yarra Glen when fire surrounded the town on three sides.[58] Houses just to the north of Yarra Glen were destroyed and large areas of grassy paddocks burnt.

Investigators strongly believe that the cause of the fire that originated near the Murrundindi Mill and swept through Narbethong and Marysville was arson, with several suspects under investigation.[59] On 1 April, Victoria Police confirmed their view that the cause was arson.[60]

Beechworth fire

In Beechworth, a fire burnt over 30,000 hectares (74,000 acres) and threatened the towns of Yackadandah, Stanley, Bruarong, Dederang, Kancoona, Kancoona South, Coralbank, Glen Creek and Running Creek.[61] The fire ignited from a felled power line at around 6 pm[31] on 7 February, 3 km (1.9 mi) south of Beechworth, before being driven south through pine plantations by hot northerly winds.[62]

The fire destroyed an unknown number of buildings at Mudgegonga, south-east of Beechworth; with two residents confirmed dead.[63] Dense smoke and cloud cover had hindered assessment of the Beechworth fire, but as conditions cleared late on 8 February, aerial crews were able to commence surveys of the situation.[64]

Strong winds fuelled the fire on the night of 8 February, and lightning ignited a new fire near Kergunyah around midday on 9 February.[65] More than 440 personnel worked to contain a separate front that threatened Gundowring and Eskdale, having jumped the Kiewa River; late on the night of 9 February the greatest threat was to Eskdale, and fires were also burning in pine plantations 8 kilometres (5.0 mi) from the large town of Myrtleford, at the opposite, western end of the fire area.[65] While smaller towns to the east, including Gundowring and Kergunyah, remained under threat, the CFA said that there was no immediate danger to the larger towns of Beechworth and Yackandandah on the northern fringe of the fire area.[66]

By 10 February, firefighters had completed a 115 km (71 mi) containment line around the Beechworth fire, and sought to construct 15 km (9.3 mi) more, though the fire continued to burn out of control.[67] By that afternoon, threat messages for the area had been downgraded, though firefighters were tackling a separate fire near Koetong, to the east of the main Beechworth fire, of between 50 to 80 ha (120 to 200 acres).[68] Residents of Beechworth and surrounding towns were advised on the evening of 10 February to expect increased smoke cover as 250 firefighters would be undertaking backburning to eliminate fuel within the control lines.[69]

The Beechworth Correctional Centre minimum-security prison offered up to thirty of its inmates to provide assistance to firefighters; a local DSE manager said that though untrained personnel would not be allowed at the fire front, the prisoners would be welcome in support roles.[67]

Bendigo fire

A fire to the west of the city of Bendigo burned out 500 hectares (1,200 acres).[70] The fire broke out at about 4:30 pm on the afternoon of 7 February, and burned through Long Gully and Eaglehawk, coming within 2 km (1.2 mi) of central Bendigo, before it was brought under control late on 7 February.[70] It destroyed around 61 houses[71] in Bendigo's western suburbs, and damaged an electricity transmission line, resulting in blackouts to substantial parts of the city.[72] One Long Gully resident, ill and confined to his house, was killed in the fire despite the efforts of his neighbours to rescue him.[72] The fire changed direction late on 7 February with the cool change, and headed back towards Eaglehawk; it was contained at 9:52 PM, though it was still burning within containment lines well into February 8.[73]

A relief centre was set up at Kangaroo Flat Senior Citizens Centre.[74] During the fire, residents from Long Gully, Eaglehawk, Maiden Gully, California Gully and West Bendigo were evacuated and advised to assemble at the centre.[75] A town meeting was held for the affected residents on 8 February.[70] On the same day, the Victoria Police indicated that they were investigating whether arson was the cause of the fire.[70]

The CFA initially suspected that the most likely cause was a cigarette butt discarded from a car or truck along Bracewell Street in Maiden Gully.[76] However, the arson squad and local Bendigo detectives spent 9 February investigating the fire scene, and while they could not determine exactly what had caused the fire as of 10 February, they suspected arson.[77] On 10 June 2009, Victoria Police announced that they were 'completely satisfied' that the fire had been deliberately lit.[78]

On 2 February 2010, police announced that the taskforce investigating the arson had arrested two youths in relation to the Bendigo fires. The youths, aged 14 and 15, were each charged with arson causing death, deliberately lighting a bushfire, lighting of a fire on a day of total fire ban, and lighting of a fire in a country area during extreme weather conditions. They were also charged with multiple counts of using telecommunications systems to menace, harass and offend and 135 counts each of arson.[79]

Redesdale fire

In Redesdale, a fire starting 9 km (5.6 mi) west of the town burnt 10,000 ha (25,000 acres) and destroyed 12 houses and various outbuildings. The fire threatened the towns of Baynton and Glenhope.[citation needed] Glenhope was threatened again on 9 February from a smaller fire that broke away from the main front, resulting in extra fire crews being brought in from Bendigo and Kyneton.[80] The fire was contained by February 10.[80]

Bunyip State Park fire

A fire started at Bunyip Ridge in the Bunyip State Park on 4 February, originating near walking tracks; it was thought to have been deliberately lit.[25] By 6 February, the fire had burned out 123 hectares (300 acres), and emergency services personnel engaged in fighting the fire feared, despite efforts to establish containment lines in the park, that once the extreme weather conditions of 7 February arrived the fire would escape the confines of the park and threaten surrounding towns.[81]

By the morning of 7 February, the fire had broken through containment lines.[82] According to the DSE incident controller for the fire, the weather conditions deteriorated much more quickly than predicted, stating that "conditions overnight and in the early hours are usually mild, but our firefighters are reporting strong winds and flame heights of five to 10 metres".[83] Ground-based fire crews had to retreat from the fire front, as the escalating conditions made firefighting in the bushland terrain impossible.[84] The fire broke out of the park around 4:00pm, and by 6:00pm had burnt out 2,400 hectares (5,900 acres) of forest and farmland, threatening the towns of Labertouche, Tonimbuk, Drouin and Longwarry, and embers were starting spot fires up to 20 km (12 mi) to the south.[85]

The fire destroyed approximately a dozen houses at Labertouche, Tonimbuk and Drouin West,[86] in addition to various outbuildings and a factory.[87] The progress of the fire had been stopped by the afternoon of 9 February, though it had burned through 24,500 hectares (61,000 acres).[88] DSE crews conducted backburning operations to ensure containment of the fire on 9 February, warning residents of areas between Pakenham and Warragul about smoke from those fires.[87]

The fire was controlled and co-ordinated at the Pakenham ICC in the Combined Emergency Services building, with CFA and DSE personnel running the operation depending on where the fire was at the time. Pakenham VICSES, who shared the building, also provided assistance during the fire operation.

West Gippsland fires

The West Gippsland bushfires began in a pine plantation 1 km (1,100 yd) south-east of Churchill at about 1:30pm on the afternoon of 7 February.[89] Within 30 minutes it had spread to the south-east, threatening Hazelwood South, Jeeralang, and Budgeree East; by late afternoon the fire was approaching Yarram and Woodside on the south Gippsland coast.[89] The cool change came through the area about 6:00pm, but the south-westerly winds it brought pushed the fire north-east through Callignee (destroying 57 of its 61 homes),[90] Koornalla and Traralgon South, and towards Gormandale and Willung South on the Hyland Highway.[89] About 500 evacuees from the area sheltered at an emergency centre established in a theatre in Traralgon.[89]

The fire threatened the Loy Yang Power Station, particularly the station's open-cut coal mine.[91] On the night of 7 February, the fire approached the mine's overburden dump, but did not damage any infrastructure, nor did it affect the station's operations.[92] Several small fires broke out in the bunker storing raw coal from the mine, but were contained with no damage.[92] The threat eased by the evening of 8 February as temperatures cooled and some light rain fell; one small spot fire broke out to the south of the power station, but it was contained by water bombing aircraft.[91]

By 9 February, the Churchill fire complex was still burning out of control, with fronts through the Latrobe Valley and the Strzelecki Ranges.[93] By late that afternoon, the complex had burnt out 32,860 hectares (81,200 acres) and had killed eleven people.[94] Wind changes that evening exacerbated parts of the Churchill complex, causing the CFA to issue further warnings to residents at Won Wron and surrounding areas.[95]

Investigators revealed that they strongly believed arson is the most likely cause of the Churchill fire.[59] A man from Churchill was arrested by police in relation to the Churchhill fires at 4:00pm on 12 February and was questioned at the Morwell police station, before being charged with one count each of arson causing death, intentionally lighting a bushfire and possession of child pornography the next day.[96] On 16 February, a suppression order was lifted and the accused arsonist was named in the media as Churchill resident Brendan Sokaluk, 39.[97]

Dandenong Ranges fire

In Upper Ferntree Gully, a fire damaged the rail track and caused the closure of the Belgrave railway line as well as all major roads.[98] The fire, which was contained by CFA crews within three hours, burned at least 2 ha (4.9 acres) along the railway.[99]

In the southern Dandenong Ranges, bushfires ignited around Narre Warren, one of which was caused by sparks from a power tool.[100] Six homes were destroyed in Narre Warren South and three in Narre Warren North.[101].

In the weeks following Black Saturday, fires were started in bushland along Terrys Avenue in Belgrave (which was contained and extinguished thanks to a speedy response from the CFA), and Lysterfield State Forest in Upwey; among other things destroyed was the few days old Upper Ferntree Gully Tanker 1 of the CFA.

Wilsons Promontory fire

On 8 February lightning sparked a fire in Wilsons Promontory which has as of the 17th burnt more than 11,000 ha (27,000 acres).[102] This fire posed no immediate threat to campers but due to excessive fuel and inaccessibility authorities chose to evacuate the park, with some campers being evacuated by boat.[103]

At a community meeting on 11 February, DSE and Parks Victoria authorities revealed a plan to backburn across the entrance to the promontory, in order to prevent any possibility of the fire burning out of the park and into farmland and towards the towns of Yanakie and Sandy Point.[104] Crikey reported that locals were divided on the merits of the plan, some concerned as to why the backburning had not been carried out earlier, and some worried at the large scale of the proposed burns, that were reportedly to be larger than both the existing fire and also the April 2005 fires that affected the park[105] Strong easterly winds on 12 February, however, forced authorities to postpone the proposed burns lest they themselves pose a danger to surrounding communities, though they did proceed with preparatory work.[106].

As of 16 February, the fire had advanced to be 7.5 kilometres (4.7 mi) away from the park entrance, but was not threatening any towns.[107].

Maroondah/Yarra fires

The Maroondah/Yarra complex was a combination of several fires that had earlier been burning to the east of Healesville and Toolangi on 10 February, as part of the greater 'Kilmore-Murrindindi Complex South'.[108] By late that morning, the complex had burned out 505 hectares (1,250 acres), with 184 personnel and 56 tankers responding to the fires.[108] A CFA spokesperson said that while temperatures had cooled, strong winds were proving problematic, with towns in the area being threatened by embers blown from the fires.[108] Around midday, the immediate threat to property in the areas around Healesville was downgraded, though a DSE spokesperson said that residents should be mindful of localised changes in the weather.[109]

Horsham fire

The Horsham fire burnt 5,700 ha (14,000 acres), including the golf club and eight homes.[45] The Dimboola fire ute was also destroyed.[110]

The fire was ignited at 12.30 pm on 7 February when strong winds initiated the failure of a 40-year-old tie wire, felling a power line at Remlaw, west of the city,[111] before heading south-west and then south-east, across the Wimmera Highway and Wimmera River to the Horsham Golf Course and then to Haven, south of the city.[112] Firefighters managed to save the general store, town hall and school at Haven, though flames came within metres of those buildings.[113] Winds of up to 90 km/h (56 mph), that changed direction three times throughout the day, produced conditions described by the local CFA incident controller as the worst he had ever seen.[111] To the south-west of Horsham, a taxi driver collected his fare, an 82-year-old wheelchair-bound woman and her daughter, from her house as the fire was no more than 100 m (110 yd) away; the house was alight as the taxi drove off, and burned down within minutes.[114]

At 3 pm more than 400 personnel were engaged in fighting the fire,[112] as well as two water-bombing aircraft, 54 Country Fire Authority (CFA) tankers and 35 Department of Sustainability and the Environment (DSE) units.[113] By 6 pm the front had moved east, and as the wind changed, was then pushed north-east across the Western Highway to Drung, east of Horsham.[112]

Coleraine fire

Shortly before 12:30pm on 7 February 2009 a fire started on farmland, 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) north-west of Coleraine in western Victoria.[115] In gusting winds, a corroded tie wire holding a 48 year old SWER conductor to an insulator failed due to metal fatigue.[115] The insulator was atop Pole 337°34′51.7″S 141°38′28.8″E / 37.581028°S 141.641333°E on the 12,700-volt Colfitz North spur line. The galvanised steel conductor swung free in the wind, suspended by poles 2 and 4, a span of 540 metres. It is not believed to have touched the ground but was pushed into a nearby eucalyptus tree by the strong prevailing wind. Burning gumleaves fell to the ground and ignited grass. The fire grew extremely rapidly in the hot, dry and windy conditions.[115] Over 230 firefighters, with 43 appliances and two water bombing aircraft, worked to contain the fire which burnt 770 ha (1,900 acres).[116] The fire destroyed one house, two haysheds, three tractors, the Coleraine Avenue of Honour and 200 km of fences [115] as well as injuring livestock, but firefighters were able to save six other homes, including that of the parents of Victorian Premier John Brumby.[116] The fire threatened to burn through the township, but a wind change around 2pm pushed the fire to the north-east instead.[117] The regional CFA operations officer said of the wind change that "[a]ll that happened within about an hour and we were lucky; we thought it would go through Coleraine, but it headed off at the last minute."[117] At about 6pm the fire was controlled.[117]

A local man was badly burned while helping a farmer move livestock out of harms way; the man was caught when the same wind change that saved the town pushed the fire in his direction, and suffered burns to 50% of his body.[116] Within a month the man was making a good recovery after extensive skin grafting by burns specialists.[118]

Weerite fire

At Weerite, east of Camperdown, a fire burnt 1,300 ha (3,200 acres), and damaged the rail line between Geelong and Warrnambool.[119] Approximately 3000 sleepers were burnt across a 4-kilometre (2.5 mi) section of track.[120] The rail line was re-opened by Monday 16 February.[121]

The fire caused unquantified losses of stock, and destroyed several outbuildings, but all houses under threat were saved by CFA firefighters.[122] The fire is thought to have been started by sparking felled power lines along the Princes Highway, which carried restricted speeds for a short time due to the heavy smoke in the area.[123]

Investigations

Investigations began almost immediately following the fires to determine a wide variety of things including; identification of victims, cause of ignition sources, authority response assessments and much else. In April, a Royal Commission into the Black Saturday bushfires began hearing, a process that is intended to determine the true nature of circumstances, chronology, etc of the events in question.

Forensic

Chief Commissioner of the Victoria Police, Christine Nixon, formed a taskforce to assist in identifying victims, coordinated by Inspector Greg Hough.[124][125] Around 40 police from interstate and overseas are assisting with Disaster Victim Identification. The police are from Tasmania, New South Wales, Australian Federal Police, Queensland, Northern Territory, Western Australia, New Zealand and Indonesia. New Zealand police have provided four victim identification dogs and handlers.[126] New Zealand has also sent a team of DVI-trained police officers on a three-week assignment.[127]

Criminal

Some of the fires are suspected to have been deliberately lit by arsonists — whose action has been described as "mass murder" by the Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd.[128]

Chief Commissioner Nixon stated on 9 February that all fire sites would be treated as crime scenes.[129] On that day a man was arrested in connection with the fires at Narre Warren; it was alleged by police that he had been operating a power tool, sparks from which ignited a grass fire, destroying two houses.[129]

On 12 February, two people were arrested in connection with the fires, having been observed by members of the public acting suspiciously in areas between Yea and Seymour; although they were both released without charges laid.[130]

A man from Churchill was arrested by police on 12 February, in relation to the Churchill fires, and was questioned at the Morwell police station, before being charged on 13 February with one count each of arson causing death, intentionally lighting a bushfire and possession of child pornography.[96] At a file hearing in the Magistrates' Court in Melbourne on 16 February, the man was remanded in custody ahead of a committal hearing scheduled for 26 May.[131] Following the hearing, a suppression order on the 39-year-old man's identity was lifted, though the order remained in force with respect to publishing his address or any images of him.[131] Despite the order, several members of the social networking website Facebook published the man's photograph (obtained from his MySpace profile) and address on the site, and others made threats of violence against him.[132] The man's lawyer said that, as a consequence of that information being published, threats were made against the man's family.[133] The man's ex-girlfriend and her family were also harassed after the Herald Sun newspaper published a photograph and a story about her.[134] On 17 February, after requests from Victoria Police, the man's MySpace profile was removed; Facebook commenced deleting postings containing threats, and deleted a photo from one group.[133]

Royal Commission

Premier John Brumby announced that there will be a Royal Commission into the fires, which will examine "all aspects of the government's bushfire strategy",[135][136] including whether climate change contributed to the severity of the fires.

Consequences

Casualties

A total of 173 people were confirmed to have died as a result of the fires.[3][137] The figure was originally estimated at 14 on the night of February 7, and steadily increased over the following 2 weeks to 210.[3] It was feared that it could rise as high as 240-280,[138] but these figures were later revised down to 173 after further forensic examinations of remains, and after several people previously believed to be missing were accounted for.[137]

A temporary morgue was established at the Coronial Services Centre at Southbank, capable of holding up to three hundred bodies, which the Victorian Coroner compared to a similar facility established after the July 2005 London bombings.[139] By the morning of February 10, 101 bodies had been transported to the temporary morgue.[139] The Victorian Institute of Forensic Medicine stated that it may well be impossible to positively identify many of the remains.[140]

On February 11, fire authorities estimated that as many as 100 of Marysville's 519 residents could have perished.[141] This figure was later downgraded to 34 after a large group of residents who remained unaccounted for were officially located.

By February 16, over 150 forensic investigators were still engaged in searching the ruins of Marysville, which was almost completely destroyed in the fires.[142] A senior lecturer in fire ecology from the University of Melbourne estimated that the fires may have been burning at temperatures of 1,200 °C (2,190 °F), and concluded that as a result, the remains of some people caught in the fires may have been obliterated.[142]

Among the dead in the Kinglake West area were former Seven Network and Nine Network television personality, Brian Naylor and his wife Moiree.[143][144][145] Actor Reg Evans and his partner, artist Angela Brunton, residing on a small farm in the St Andrews area, also died in the Kinglake area fire.[146][147] Ornithologist Richard Zann perished in the Kinglake fire, together with his wife Eileen and daughter Eva.[148]

66 of those killed in the fires had been positively identified by March 20, 2009.

Foreign nationals killed in the bushfire included citizens of:

- Greece - 2 [149]

- Philippines - 2 [150]

- Indonesia - 2 [citation needed]

- Chile - 1 [151]

- New Zealand - 1 [152]

- United Kingdom - 1 [153]

Injuries

A total of 414 people were injured during the Black Saturday bushfires. Due to the intensity and speed of the fires, most people injured in the bushfires either died or survived with minor injuries, with significantly fewer major burns than previous bushfires such as Ash Wednesday. Of the people who presented to medical treatment centres and hospitals, there were 22 with serious burns and 390 with minor burns and other bushfire-related injuries. National and statewide burns disaster plans were activated. 22 patients with major burns presented to the state’s burns referral centres, of which 18 were adults. One patient admitted to the Royal Children’s Hospital and 2 at The Alfred died from their injuries. Adult burns patients at The Alfred spent 48.7 hours in theatre in the first 72 hours. There were a further 390 bushfire-related presentations across the state in the first 72 hours. Most patients with serious burns were triaged to and managed at burns referral centres. Throughout the disaster, burns referral centres continued to have substantial surge capacity.[5]

Fatalities

- Kinglake/Whittlesea Area (120)

- 38 – Kinglake

- 27 – Strathewen

- 12 – St Andrews

- 10 – Steels Creek

- 10 – Hazeldene

- 6 – Humevale

- 4 – Kinglake West

- 2 – Flowerdale

- 2 – Whittlesea

- 2 – Toolangi

- 2 – Arthurs Creek

- 1 – Clonbinane

- 1 – Heathcote Junction

- 1 – Strath Creek

- 1 – Upper Plenty

- 1 – Yarra Glen

- Marysville Area (39)

- 34 – Marysville

- 4 – Narbethong

- 1 – Camberville (ACT firefighter)

- West Gippsland (11)

- Beechworth (2)

- 2 – Mudgegonga

- Bendigo (1)

- 1 – Eaglehawk

Statistics

- Out of the 173 deaths, 100 were male and 73 were female.

- 164 people died in the fires themselves, 5 died later in hospital and 4 died from other causes including car crashes.

- 7 of the deaths occurred in bunkers of both fire-specific and non-fire-specific design.

- Location:[155]

- 113 - inside houses

- 27 - outside houses

- 11 - in vehicles

- 6 - in garage

- 5 - near vehicle

- 5 - on roadway

- 4 - attributed to or associated with the fire but not within fire location

- 1 - on reserve

- 1 - in shed

Firefighter fatality

An ACT firefighter was killed near Cambarville on the night of 17 February, when a burnt-out tree collapsed onto his fire tanker.[156] He was the only working firefighter killed during the 2009 Victorian bushfires.

Overall Statistics

- 450,000 ha (1,100,000 acres) burnt

- 414 people injured

- 7,562 people displaced

- Over 3,500 structures destroyed, including;

- 2,029+ houses

- 59 commercial properties (shops, pubs, service stations, golf clubs, etc)

- 12 community buildings (including 2 police stations, 3 schools, 3 churches, 1 fire station)

- 399 machinery sheds, 729 other farm buildings, 363 hay sheds

- 19 dairies, 26 woolsheds

- Structures damaged

- 25,600 tonnes (25,200 long tons; 28,200 short tons) of stored fodder and grain

- 190 ha (470 acres) of standing crops

- 168,000 ha (420,000 acres) of pasture

- 735 ha (1,820 acres) of fruit trees, olives and vines

- 7,000 ha (17,000 acres) of plantation timber

- 3,921 ha (9,690 acres) of private bushland

- 2,150 sheep, 1,207 cattle, and an unknown number of horses, goats, alpacas, poultry and pigs[157]

- Over 10,000 kilometres (6,200 mi) of boundary and internal fencing destroyed or damaged[158]

- Over 55 businesses destroyed

- About 211,000 tonnes (208,000 long tons; 233,000 short tons) of hay destroyed

- Over 11,000 livestock killed or injured

- The electricity supply was disrupted to 60,000 residents

- Several mobile phone base stations and telephone exchanges damaged or destroyed

- 950 local parks, 70 national parks and reserves, and over 600 cultural sites and historic places were destroyed[158]

- The amount of energy released during the firestorm in the Kinglake-Marysville area was equivalent to the amount of energy released by 1,500 Hiroshima-sized atomic bombs.

| Area | |||||

| Kinglake Area | |||||

| Marysville Area | |||||

| West Gippsland | |||||

| Beechworth | |||||

| Bunyip State Park | |||||

| Wilsons Promontory | |||||

| Redesdale | |||||

| Horsham | |||||

| Weerite | |||||

| Coleraine | |||||

| Maroondah/Upper Yarra | |||||

| Bendigo | |||||

| Dandenong Ranges | |||||

| Totals | |||||

International context

The Black Saturday bushfires were the 8th deadliest singular bushfire/wildfire event in recorded history:

- 1871 - Peshtigo, Wisconsin, USA - 1200

- 1918 - Cloquet, Minnesota, USA - 453

- 1894 - Hinckley, Minnesota, USA - 418

- 1881 - Thumb region, Michigan, USA - ~300

- 1916 - Matheson, Ontario, Canada - 282

- 1997 - Sumatra, Kalimantan, Indonesia - 250

- 1987 - Greater Hinggan, China - 213

- 2009 - Victoria, Australia - 173

Responses

Responses to the Black Saturday bushfires included immediate community response, donations and later, international aid efforts, Government inquiries including a Royal Commission and recommendations and discussions from a wide variety of bodies, organisations, authorities and communities. Several of these responses are currently ongoing as of September 2009.

In September 2009 it was revealed that Australia's most prominent fire ecologist, Kevin Tolhurst, is developing a new course for the University of Melbourne on fire behaviour.[159] Later that month the City of Manningham announced it was developing the state's first integrated fire management plan in conjunction with the interim findings of the Royal Commission.[160] Eventually all Victorian councils responsible for both urban and rural land will need to develop such plans, which define fire risks in open space areas, along major roads, and in parkland.

In September/October 2009, it was announced that a new fire hazard system would replace the previous one. The new system involves a 6-tier scale to advise those in affected areas of the level of risk, activity of the fire, etc. On the highest risk days, residents will be advised to leave the potentially affected areas.

Subsequent events and issues

Environmental impacts

Millions of animals are estimated to have been killed by the bushfires.[161] Additionally, of the surviving wildlife, many more have suffered from severe burns. For example, large numbers of kangaroos were afflicted with burned feet due to territorial instincts that drew them back to the recently-burned and smoldering homes.[161] The affected area, particularly around Marysville, contains the only known habitat of Leadbeater's Possum, Victoria's faunal emblem.[162]

Forested catchment areas supplying five of Melbourne's nine major dams were affected by the fires, with the worst affected being Maroondah Reservoir and O'Shannassy Reservoir.[163] As of 17 February, over ten billion litres of water had been shifted out of affected dams into others.[163] A Melbourne Water spokesperson said that affected dams may need to be decommissioned if the contamination from ash and other material were serious enough, and also said that forest regrowth in the burnt-out catchment areas could reduce runoff yields by up to 30% over three decades.[163][164]

In early March 2009, smoke from the fires was discovered in the atmosphere over Antarctica at record altitudes.[165]

Economic impact

The general insurance industry has received approximately 8,150 claims with an estimated insurable cost of $1.02 billion. However the full extent of costs to the communities will not be known for a considerable period of time.[166] Some claims adjusters suggested that the total insurance costs for the fires could amount to $1.5 billion.[167] Other industry analysts suggested that the fires would lead to rises in insurance premiums, so that insurers might recover some of their losses.[168] At the close of trading on 9 February, Suncorp Metway shares had dropped by more than a quarter, and IAG shares were down nearly ten per cent.[166]

Deputy Prime Minister Julia Gillard called on insurers to respond in a sensitive fashion to claims relating to the fires, saying "I am sure that anybody from an insurance company that has looked at their TV screens today is going to see the devastation and understand it is going to trigger claims and that those claims need to be responded to sympathetically and quickly."[166]

An economist from Goldman Sachs JBWere said that an upside of the fire situation was that reconstruction efforts were likely to produce a stimulus effect on the economy of between 0.25 and 0.4 per cent of GDP over 18 months, saying that "As tragic as the events of the past two days have been, the rebuilding phase will provide a catalyst for economic growth in coming months, even if the personal and environmental cost takes years to recover".[169]

Looting

By the morning of 11 February, reports of looting had been posted. Witnesses reported seeing acts of looting occurring at a property at Heathcote Junction, shortly after the removal of the body of a victim from the property.[170] That evening, via a report on ABC Local Radio, a number of residents of Kinglake who had been allowed back into the area to inspect the damage, revealed that a "Looters Will Be Shot" sign had been posted in the town, after a number of suspicious people and vehicles were seen moving through the town.

On 12 February, a small number of arrests were made, and charges laid against people in relation to "looting offences", as announced by Police Chief Commissioner Christine Nixon.[171]

Lawsuits

A class action lawsuit was initiated in the Supreme Court of Victoria on 13 February by Slidders Lawyers against electricity distribution company SP AusNet, in relation to the Kilmore East fire that became part of the Kinglake complex, and the Beechworth fires.[172] A partner at the firm indicated that the claim would centre on alleged negligence by SP AusNet in its management of electricity infrastructure.[172] On 12 February police had taken away a section of power line as well as a power pole from near Kilmore East, part of a two-kilometre section of line that fell on the morning of 7 February and was believed to have started the fire there.[172]

A separate class action claim was expected to be commenced by Gadens Lawyers some time after 16 February, and Slater & Gordon indicated that they were awaiting the report of the to-be-established Royal Commission, expected in late 2010, before initiating any claims.[172]

Also on 13 February, five law firms from Victoria's Western Districts held a meeting to discuss a potential class action in relation to the Horsham fire, which was also thought to have been started by fallen power lines.[172]

Climate change

While it is difficult to attribute an individual weather event, such as the current extended drought in southeastern Australia, to an overall climatic pattern such as global warming, it is possible to correlate patterns with other patterns. Although the current drought could be the result of natural weather pattern variability, it is embedded in a 50-year warming trend that can be attributed with confidence to human-induced increases in greenhouse gas emissions.[18][173]

This warming trend is, in turn, expected to continue in proportion to an increase in the intensity and frequency of Australian fires.[18][173] Following the fires, commentators such as Tim Flannery,[174] a popular scientist, Greens politician Bob Brown,[173] and leading and volunteer firefighters[175][176]argued that the number of extreme fire days in Australia is likely to increase substantially due to climate change and that governments should therefore invest more energy combating it. A recent study by the Australian Bureau of Meteorology and the CSIRO which found that fire-weather risk is likely to increase at most sites considered from 2020 to 2050 was cited in support.[177] A report by Greenpeace and a firefighters union found that "mega-fires" could occur once every three years in the bush around Melbourne.[178]

However, a study completed after the bushfires by the CSIRO found that the Indian Ocean Dipole was at least partially to blame [179] [180]. As the bushfires were largely as a result of extreme temperatures and dryness, the phenomenon has also been to blame for the long drought that Australia has suffered for many years [181], hence resulting in the same conclusions being reached. [182]

Fire policy

In the wake of the fires, and the mounting casualty toll, there was debate about policies for dealing with bushfires.

In announcing that the fires would be investigated by a Royal Commission, Victorian Premier John Brumby suggested that the long-standing 'stay-and-defend-or-leave-early' policy would be reviewed, saying that while it had proven reliable during normal conditions, the conditions on 7 February had been exceptional.[183] Brumby said that "There were many people who had done all of the preparations, had the best fire plans in the world and tragically it didn't save them."[184] However, Commissioner Nixon defended the policy, saying that it was "well thought of and well based and has stood the test of time and we support it."[185] Similarly, Commissioner of the New South Wales Rural Fire Service Shane Fitzsimmons said that "Decades of science, practice and history show that a well-prepared home provides the best refuge in the event of fire".[183] Nixon also dismissed potential policies involving forced evacuations, saying "There used to be policies where you could make people leave but we're talking about adults".[185] Former Victorian police minister Pat McNamara argued that forced evacuations could have worsened the death toll, as many of the dead appeared to have been killed while attempting to evacuate the fire areas by car.[184]

Naomi Brown, chief executive of the Australasian Fire and Emergency Services Authorities Council, argued that the high number of fatalities in these fires, as opposed to earlier fires such as the Ash Wednesday fires, was partly attributable to increased population densities at Melbourne's fringes.[184] David Packham, research fellow at Monash University, argued that high fuel loads in bushland led to the destructive intensity of the fires, saying that "There has been total mismanagement of the Australian forest environment".[184] Federal member of parliament and former forestry minister Wilson Tuckey also identified high fuel loads as a key contributor to the destruction, saying "Governments who choose to lock up these forests and... treat them with benign contempt, well, others pay the penalty".[186] Tuckey put the blame for fuel loads on the two major parties – Labor and the Coalition – asserting that they "go running around putting in more reserves to get Green preferences".[186] Nationals Senator Ron Boswell also argued for changes to forestry management policies, saying that "I'm not blaming anyone for this, I just think we need to look at some areas we turn into parks and then can't defend them".[187]

Building codes debate

The Victorian government intends to debate new fire related planning and building code standards. In response to the Victorian bushfires new building regulations for bushfire-prone areas have been fast tracked by Standards Australia.[188][189] Victoria has no separate building code for bushfire-prone areas. In New South Wales building laws for bushfire-prone areas are incorporated in planning legislation using a 1090 Kelvin(K) (817 °C (1,503 °F)*) level as the assumed temperature to which houses are subject when hit by bushfire. A draft national building code for bushfire-prone areas is proposing to use 1000K (727 °C (1,341 °F)*) as the standard. Fire engineers say that standards should be based on a 1090K (817°C) temperature. The temperature of fires can peak at approximately 1600K/1,300 °C (2,370 °F)*.[190]

Banning housing in highest risk areas

An expert panel recommended in 2010, that the state government ban housing in the highest fire risk areas, which are some of the most dangerous in the world. [2]

Pr. Michael Buxton of RMIT said that after the 1983 Ash Wednesday fires, the government bought back tens of thousands of lots across the Dandenong Ranges, because they were extremely high fire risk areas. [3]

The International Planning expert, Pr. Roz Hansen said that in other parts of the Asia-Pacific region, people have been forcibly moved out of high risk cyclone and flooding areas. [4]

Russian waterbombers

In October 2009, at the Royal Commission, the Russian Ambassador to Australia said that the Russian Government had offered the Australian Government two advanced Ilyushin Il-76 waterbombers to help put out the bushfires. The offer was forwarded to the Victorian authorities, but the DSE declined it due to the aircraft not being suitable for the conditions in Victoria and the time it would have taken for approval from aviation authorities.[191] Ilyushin Il-76 waterbombers have the capacity to drop 42,000 litres of water in a single pass.[192]

Gallery

-

Damage to a carport in Steels Creek, February 10

-

Property damage in Yarra Glen, February 10

-

Acheron Way, showing regrowth, April 10

-

Lake Mountain toboggan run, April

See also

References

- ^ Gorman, Paul (9 February 2009). "Heat wave fails to arrive". The Press. Fairfax New Zealand. Retrieved 9 February 2009.

- ^ COLLINS, PÁDRAIG (12 February 2009). "Rudd criticised over bush fire compensation". Irish Times. Retrieved 19 February 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f "Bushfires death toll". Victoria Police. 30 March 2009. Event occurs at 1707. Retrieved 31 March 2009.

- ^ "Toll capped at 210". Herald Sun. 22 March 2009. Event occurs at 12:00. Retrieved 22 March 2009.

- ^ a b Australian Medical Journal article abstract

- ^ Marysville fire deliberately lit: police Reko Rennie (1 April 2009) theage.com.au

- ^ a b "Bushfires in Victoria kill 35, fears death toll will rise". Herald Sun. 8 February 2009. Retrieved 8 February 2009.

- ^ a b "State Summary Overview - 9th Feb 2009 - 2115 hrs" (PDF). Victorian Government. Country Fire Authority. 9 February 2009. Retrieved 9 February 2009.

- ^ "Lightning starts new bushfires in Grampians". ABC News. 8 February 2009. Retrieved 9 February 2009.

- ^ a b "Police track arsonists responsible for Victoria bushfires". The Australian. 10 February 2009. Retrieved 14 February 2009.

- ^ "Counting the terrible cost of a state burning". The Age. 9 February 2009. Retrieved 15 February 2009.

- ^ "Horrific, but not the worst we've suffered". Sydney Morning Herald. 11 February 2009. Retrieved 11 February 2009.

- ^ "Bushfire death toll revised down". News.com.au. 30 March 2009. Retrieved 30 March 2009.

- ^ a b "Victorian Bushfires". Parliament of New South Wales. 13 March 2009. Retrieved 14 December 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|published=ignored (help) - ^ "Marysville almost destroyed in Victorian bushfires". Sydney Morning Herald. 8 February 2009. Retrieved 8 February 2009.

- ^ "'Absolute devastation': Victoria gutted by deadly bushfires". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 8 February 2009. Retrieved 7 February 2009.

- ^ "Cigarette butt blamed for West Bendigo fire; two dead, 50 homes lost". News.com.au. 9 February 2009. Retrieved 9 February 2009.

- ^ a b c "Q&A: Victorian bushfires (fact sheet)". CSIRO. 12 February 2009. Retrieved 18 February 2009.

- ^ FACTBOX: The world's water and climate change (Reporting by Ed Stoddard, editing by Mary Milliken)(9 March 2009)Reuters

- ^ "The exceptional January-February 2009 heatwave in south-eastern Australia" (PDF). Bureau of Meteorology. National Climate Centre. 12 February 2009. Retrieved 18 November 2009.

- ^ a b Townsend, Hamish (7 February 2009). "City swelters, records tumble in heat". The Age. Retrieved 7 February 2009.

- ^ a b Moncrief, Mark (6 February 2009). "'Worst day in history': Brumby warns of fire danger". The Age. Retrieved 11 February 2009.

- ^ Karoly, David (16 Feb 2009). "Bushfires and extreme heat in south-east Australia". Real Climate. Retrieved 17 February 2009.

- ^ "Gippsland faces third fire". Weekly Times. 29 January 2009. Retrieved 11 February 2009.

{{cite news}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ a b Miller, Elisa (12 February 2009). "Battle to control Bunyip State Park blaze". Berwick & District Journal. Retrieved 22 February 2009.

- ^ "Hill paddock is pinpointed as area where fire started". Herald Sun. 12 February 2009. Retrieved 17 February 2009.

- ^ "Horsham fire: The latest report". The Wimmera Mail-Times. Fairfax Media. 8 February 2009. Retrieved 18 February 2009.

- ^ "transcript page 8208, Victorian Bushfires Royal Commission". Victorian Government. 6 October 2009. Retrieved 10 February 2010.

- ^ "The trail of destruction ... and the outlook". The Age. Fairfax Media. 9 February 2009. Retrieved 18 February 2009.

- ^ a b Stewart, Cameron (14 February 2009). "How the battle with Victoria's bushfires was fought and lost". The Australian. News limited. Retrieved 17 February 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) Cite error: The named reference "australian how the battle" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ a b "Beechworth Area Fire - Community Update Newsletter" (PDF). Country Fire Authority. 13 February 2009. Event occurs at 9 am. Retrieved 18 February 2009.

- ^ Strong, Geoff (5 March 2009). "Marysville residents recall Black Saturday for police probe". The Age. Retrieved 7 March 2009.

- ^ Milovanovic, Selma (6 April 2009). "Marysville residents 'should have been warned to leave town". The Age. Retrieved 10 April 2009.

- ^ "Yarra Valley tourist town Marysville devastated by bushfire". Herald Sun. 8 February 2009. Retrieved 22 February 2009.

- ^ "Tidal River camping ground evacuated as fire spreads". ABC News. 9 February 2009. Retrieved 22 February 2009.

- ^ a b c d "Winds cause nervous moments for Healesville". The Age. 17 February 2009. Retrieved 17 February 2009.

- ^ CFA Awareness Message - Bunyip Ridge Track Fire 7.00pm, 27/02/2009

- ^ CFA Downgrade Message - Alert to Awareness-Kilmore East Murrindindi Complex North Fire, 27/02/2009

- ^ CFA Awareness Message - Kilmore East - Murrindindi Complex South Fire 7.20 pm, 27/02/2009

- ^ CFA Awareness Message - Wilsons Prom Cathedral Fire 6.00pm, 27/02/2009

- ^ Awareness Message - French Island Fire 6.50pm, 27/02/2009

- ^ Dobbin, Marika (3 March 2009). "Victorians receive fire text warning". The Age. Retrieved 3 March 2009.

- ^ "Reports of major casualties at Kinglake". Geelong Advertiser. 8 February 2009. Retrieved 9 February 2009.

- ^ "At a glance: where bushfires are burning". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 8 February 2009. Retrieved 9 February 2009.

- ^ a b "Death toll may reach more than 40: police". The Age. 7 February 2009. Retrieved 7 February 2009.

- ^ "Kilmore fires cause grave concern". Geelong Advertiser. 8 February 2009. Retrieved 9 February 2009.

- ^ "Grieving Victoria takes stock as toll nears 100". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 9 February 2009. Retrieved 9 February 2009.

- ^ "transcript pages 8208, 8225 & 8246, Victorian Bushfires Royal Commission". Victorian Government. Retrieved 10 February 2010.

- ^ "Detective Superintendent Paul Hollowood's witness statement paragraph 65". Victorian Government. Retrieved 10 February 2010.

- ^ "Detective Superintendent Paul Hollowood's supplementary witness statement, paragraph 20". Victorian Government. Retrieved 10 February 2010.

- ^ "transcript page 8261, Victorian Bushfires Royal Commission". Victorian Government. Retrieved 10 February 2010.

- ^ "Wiped out: Towns destroyed by killer fires". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 7 February 2009.

- ^ a b Cowan, Jane (8 February 2009). "Wiped out: Town destroyed by killer fires". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 9 February 2009.

- ^ Davies, Julie-Anne (9 February 2009). "Razed township fears for missing". The Australian. Retrieved 9 February 2009.

- ^ Coslovich, Gabriella (9 February 2009). "Sickening wait for proof of life, or death". The Age. Retrieved 9 February 2009.

- ^ "Bushfires toll at 181. Marysville toll may be one in five". Herald Sun. 11 February 2009. Retrieved 11 February 2009.

- ^ "Yea-Murrundindi map" (PDF). CFA. Retrieved 8 February 2009.

- ^ "'We can see flames': people stranded in Yarra Glen". The Age. 8 February 2008. Retrieved 8 February 2009.

- ^ a b "Arsonists my have lit Marysville fire - Nixon". The Age. 12 February 2009. Retrieved 12 February 2009.

- ^ http://www.theage.com.au/national/marysville-fire-deliberately-lit-police-20090401-9j39.html

- ^ "Smoke, cloud restrict Beechworth fire info". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 8 February 2009. Retrieved 8 February 2009.

- ^ "Fast-moving blaze hit with little warning". Herald Sun. 9 February 2009. Retrieved 9 February 2009.

{{cite news}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ "Buildings destroyed near Beechworth". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 8 February 2009. Retrieved 8 February 2009.

- ^ "Smoke, cloud restrict Beechworth fire info". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 8 February 2009. Retrieved 8 February 2009.

- ^ a b Pilcher, Georgie (10 February 2009). "Fresh fire jumps river and threatens towns". Herald Sun. Retrieved 10 February 2009.

- ^ "Inquiry ordered into Victoria bushfires, hunt for arsonists begins". The Australian. 10 February 2009. Retrieved 10 February 2009.

{{cite news}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ a b "Prisoners help fight Beechworth blaze". Canberra Times. 10 February 2009. Retrieved 10 February 2009.

- ^ "North-east residents urged to remain on fire alert". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 10 February 2009. Retrieved 10 February 2009.

- ^ "Smoke increases with Beechworth backburning". Border Mail. 10 February 2009. Retrieved 10 February 2009.

- ^ a b c d "Meeting held for fire-affected Bendigo residents". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 9 February 2009. Retrieved 9 February 2009.

- ^ http://www.bendigoadvertiser.com.au/news/local/news/general/inferno-warning-cfa/1435265.aspx

- ^ a b "The man up the road is on fire". Herald Sun. 9 February 2009. Retrieved 9 February 2009.

- ^ Kennedy, Peter (9 February 2009). "'Fire had a mind of its own, like a beast'". The Age. Retrieved 9 February 2009.

- ^ "Downgrade Message - Urgent Threat to Final Advice Bracewell Fire (Bendigo), 2.30 am". CFA. Retrieved 8 February 2009.

- ^ "BENDIGO BATTLES WALL OF FLAMES". Bendigo Advertiser. 8 February 2009. Retrieved 9 February 2009.

- ^ Perkin, Corrie (9 February 2009). "Cigarette butt blamed for West Bendigo fire; two dead, 50 homes lost". News Limited. News.com.au. Retrieved 9 February 2009.

- ^ "Arson suspected in deadly Bendigo blaze". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 10 February 2009. Retrieved 10 February 2009.

- ^ Cooper, Mex (10 July 2009). "Black Saturday: Bendigo fatal fire 'arson'". The Age. Retrieved 14 December 2009.

- ^ "Two charged for Bendigo arson". Victoria Police. 02 February 2010. Retrieved 02 February 2010.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ a b "Arson suspected in deadly Bendigo blaze". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 10 February 2009. Retrieved 10 February 2009.

- ^ "Bushfire threatens to break free". The Australian. 6 February 2009. Retrieved 22 February 2009.

- ^ "Residents warned as fire breaks lines". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 7 February 2009. Retrieved 22 February 2009.

- ^ "Residents on high alert as fire nears". The Australian. 7 February 2009. Retrieved 22 February 2009.

- ^ "Fire crews forced to retreat". The Australian. 7 February 2009. Retrieved 22 February 2009.

- ^ "Inferno terrorises communities as it rages out of control". The Age. 7 February 2009. Retrieved 22 February 2009.

{{cite news}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ White, Leslie (11 February 2009). "Rain the only fire hope". Weekly Times. Retrieved 22 February 2009.

- ^ a b Wotherspoon, Sarah (9 February 2009). "Dozens of towns on high alert as strong winds fan flames". Herald Sun. Retrieved 9 February 2009.

- ^ "At a glance: fires of concern". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 9 February 2009. Retrieved 9 February 2009.

- ^ a b c d Jackson, Nicole (9 February 2009). "Blaze claims lives". Latrobe Valley Express. Retrieved 9 February 2009.

- ^ McGourty, John (2009). Black Saturday. Harper Collins. ISBN 9780732290108.

- ^ a b "Victoria's power 'secure but under threat'". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 8 February 2009. Retrieved 9 February 2009.

- ^ a b "Loy Yang on alert". Latrobe Valley Express. 9 February 2009. Retrieved 9 February 2009.

- ^ "Gippsland fires continue to rage". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 9 February 2009. Retrieved 9 February 2009.

- ^ "Bushfire races towards Loy Yang power station". Geelong Advertiser. 9 February 2009. Retrieved 9 February 2009.

- ^ "Shifting winds flare up fire fronts". Herald Sun. 9 February 2009. Retrieved 9 February 2009.

- ^ a b Silvester, John (13 February 2009). "Churchill arson suspect arrested". The Age. Retrieved 13 February 2009.

- ^ "Bushfire fatal arson accused named as Brendan Sokaluk". Herald-Sun. 16 February 2009. Retrieved 16 February 2009.

- ^ "Gippsland, Seymour & Warrnambool lines ~ Services suspended due to bushfires ~ Sun 8 Feb". V/Line. 8 February 2009. Retrieved 8 February 2009.

- ^ "Owners flee as fires gut homes". Herald Sun. 8 February 2009. Retrieved 9 February 2009.

- ^ "Many may be trapped in homes". Sydney Morning Herald. 8 February 2009. Retrieved 8 February 2009.

- ^ "Fire crews mop up after Narre Warren South blaze". Dandenong Leader. 8 February 2009. Retrieved 8 February 2009.

- ^ "Crews unable to slow Wilsons Promontory blaze". ABC News. 17 February 2009. Retrieved 18 February 2009.

- ^ "Tidal River camping ground evacuated as fire spreads". ABC News. 9 February 2009. Retrieved 10 February 2009.

- ^ Millar, Royce (12 February 2009). "National park at forefront of backburning debate". The Age. Retrieved 16 February 2009.

- ^ Elmore, Lionel (12 February 2009). "Parks Victoria uses the fire crisis to light up the Prom again". Crikey. Retrieved 16 February 2009.

- ^ "Winds force change to backburning plans". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 12 February 2009. Retrieved 16 February 2009.

- ^ "Prepare for day of mourning". Herald Sun. 16 February 2009. Retrieved 16 February 2009.

- ^ a b c Smith, Britt (10 February 2009). "Fires threaten Yarra Valley". The Age. Retrieved 10 February 2009.

- ^ Grace, Robyn (10 February 2009). "Healesville fire threat downgraded". The Age. Retrieved 10 February 2009.

- ^ "Horsham assesses bushfire damage". ABC South East SA. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 8 February 2009. Retrieved 20 February 2009.

- ^ a b Thom, Greg (9 February 2009). "It's frightening in the firing line". Herald Sun. Retrieved 9 February 2009.

- ^ a b c "Horsham fire: The latest report". Wimmera Mail-Times. 8 February 2009. Retrieved 8 February 2009.

- ^ a b "Haven school, hall, general store saved". Wimmera Mail-Times. 7 February 2009. Retrieved 7 February 2009.

- ^ Flitton, Daniel (9 February 2009). "Molly flees the scene of 61 good years in a cab". The Age. Retrieved 9 February 2009.

- ^ a b c d "Counsel Assisting submission re Coleraine fire". 2009 Bushfires Royal Commission. 23 December 2009. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ a b c Johnson, Alex (9 February 2009). "Man badly burnt when wind gust changes blaze direction". Warrnambool Standard. Retrieved 17 February 2009.

- ^ a b c "Coleraine saved from fire devastation". The Border Watch. 9 February 2009. Retrieved 17 February 2009.

- ^ "Bushfire burns victim takes first steps in recovery". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 9 March 2009. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ "Urgent travel advice - Train disruptions to continue on Sunday due to bush fires". VLine. VLine. Retrieved 8 February 2009.

- ^ "Rail services to get back on track". ABC Local Radio. Retrieved 11 February 2009.

- ^ "Warrnambool services - Full train service has returned". V/Line. Retrieved 17 February 2009.

- ^ "BREAKING NEWS: Fire races through Pombo". Warrnambool Standard. 8 February 2009. Retrieved 8 February 2009.

- ^ "Bush Fires - Road Closures: VicRoads". VicRoads. VicRoads. Retrieved 9 February 2009.

- ^ Moncrieff, Mark (8 February 2009). "Emotional Premier gives fire warning". The Age. Retrieved 8 February 2009.

- ^ "Months to identify bodies in Victorian bushfires, police say". The Herald Sun (from AAP). 9 February 2009. Retrieved 9 February 2009.

- ^ Victoria Police Media Release 17 February 2009. http://www.police.vic.gov.au/content.asp?Document_ID=19541

- ^ "Kiwis to help identify victims". New Zealand Herald. APN News & Media. 11 February 2009. Retrieved 11 February 2009.

- ^ "Rudd angrily denounces 'mass murder' arsonists". ABC News. 9 February 2009. Retrieved 9 February 2009.

- ^ a b "Police track arsonists responsible for Victoria bushfires". The Australian. 10 February 2009. Retrieved 10 February 2009.

{{cite news}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ Grace, Robyn (12 February 2009). "Arson suspects arrested". The Age. Retrieved 12 February 2009.

- ^ a b Rennie, Reko (16 February 2009). "Churchill arson accused fails to face court". The Age. Retrieved 16 February 2009.

- ^ Moses, Asher (16 February 2009). "Vigilantes publish alleged arsonist's image online". The Age. Retrieved 16 February 2009.

- ^ a b Moses, Asher (17 February 2009). "'Arsonist' online threats taken down". The Age. Retrieved 17 February 2009.

- ^ "Family of Brendan Sokaluk's ex-girlfriend calls for calm". The Australian. 17 February 2009. Retrieved 17 February 2009.

- ^ "Brumby announces bushfires Royal Commission". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 9 February 2009. Retrieved 9 February 2009.

- ^ "Victorian fires royal commission". Daily Telegraph. Daily Telegraph. 9 February 2009. Retrieved 9 February 2009.

- ^ a b "Victorian bushfires death toll slashed to 173". The Age. 30 March 2009. Retrieved 30 March 2009.

- ^ Dobbin, Marika (26 February 2009). "Missing may lift death toll to 240". The Age. Retrieved 26 February 2009.

- ^ a b Smith, Bridie (11 February 2009). "Identity may not be possible for all". The Age. Retrieved 11 February 2009.

- ^ "Fifty bodies may never be identified in Victoria fires". The Australian. 10 February 2009. Retrieved 11 February 2009.

- ^ "Bushfires toll at 181. Marysville toll may be one in five". Herald Sun. 11 February 2009.

- ^ a b Murdoch, Lindsay (16 February 2009). "Fire's intensity leaves no trace of victims". The Age. Retrieved 16 February 2009.

- ^ "Bushfire death toll reaches 84". Geelong Advertiser. 8 February 2009. Retrieved 8 February 2009.

- ^ "Brian Naylor and wife die in [[Kinglake, Victoria|Kinglake]] inferno". Geelong Advertiser. 9 February 2009. Retrieved 9 February 2009.

{{cite news}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help) - ^ "TV legend Brian Naylor found dead". The Herald Sun. 9 February 2009. Retrieved 9 February 2009.

- ^ "Veteran actor Reg Evans and partner feared dead". Herald Sun. 10 February 2009. Retrieved 10 February 2009.

- ^ "TV star dies with partner in Victorian Bushfires". The Australian. 11 February 2009. Retrieved 11 February 2009.

- ^ Trounson, Andrew (12 February 2009). "Birdsong expert was ready for Victoria bushfires but it was no use". The Australian. Retrieved 12 February 2009.

- ^ "Fire in Australia Kills two Greeks". Retrieved 12 February 2009.

- ^ "Two Filipinos killed in bushfires in Australia". Retrieved 12 February 2009.

- ^ "Chilena muere en incendios de Australia". Retrieved 21 February 2009.

- ^ "TBushfires claim first NZ victim". Retrieved 13 February 2009.

- ^ "BRITISH FAMILY'S GRIEF OVER BUSHFIRE VICTIMS". Retrieved 13 February 2009.

- ^ Victoria Police, Press conference: Bushfires death toll revised to 173, Release date: Mon 30 March 2009 http://www.police.vic.gov.au/content.asp?Document_ID=20350

- ^ Black Saturday data reveals where victims died, May 28, 2009, The Age

- ^ ACT firefigher killed near Marysville

- ^ The Land, "Farmers do their bit, Peter J Austin, p.12, Rural Press, 19-2-2009

- ^ a b Norther Daily Leader, 18 May 2009, "Steady progress on bushfire clean-up", p. 8

- ^ Costigan, Justine (September 2009). "Responding to Tragedy". Melbourne University Magazine. pp. 15–17. Retrieved 3 September 2009.

- ^ Crowe, Danielle (9 September 2009). "Hotspots register". Manningham Leader. p. 5. Retrieved 22 September 2009.

- ^ a b Gelineau, Kristen (11 February 2009). "Millions of animals dead in Australia fires". Associated Press. Retrieved 11 February 2009.

- ^ Last captive Leadbeater's possum dies. ninemsn.com.au. 15 April 2006.

- ^ a b c Ker, Peter (17 February 2009). "Dash to save Melbourne's drinking water". The Age. Retrieved 17 February 2009.

- ^ Roberts, Greg (17 February 2009). "Vic bushfires may affect water supplies". The Age. Retrieved 14 December 2009.

- ^ "Bushfire aftermath: smoke trapped over Antarctica". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 28 May 2009. Retrieved 14 December 2009.

- ^ Nichols, Nick (11 February 2009). "Insurance bills set to rocket". goldcoast.com.au. Retrieved 11 February 2009.

- ^ Boreham, Tim (10 February 2009). "IAG (IAG) $3.24 Sucorp Metway (SUN) $5.31". The Australian. Retrieved 11 February 2009.

- ^ "Looters move in to rob the dead at Heathcote Junction". Herald Sun. 11 February 2009.

- ^ "Alleged looters charged in bushfire aftermath". ABC Online. 13 February 2009.

- ^ a b c d e "Huge fire class action launched". The Age. 15 February 2009. Retrieved 15 February 2009.

{{cite news}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ a b c Walsh, Bryan (9 February 2009). "Why Global Warming May Be Fueling Australia's Fires". Time. Retrieved 12 February 2009.

- ^ "Australian bushfires: when two degrees is the difference between life and death". Guardian. 10 February 2009. Retrieved 18 February 2009.

- ^ Marshall, Peter (2009-02-12). "Face global warming or firefighters' lives will be ever at risk". The Age: p. 25. Retrieved 2009-02-18.

- ^ McDonald, Shaun (2009-09-09). "Government fiddles while bush burns". Green Left Weekly (809): pp. 3, 6. Retrieved 2009-09-22.

- ^ Hennessy, K (December 2005). "Climate change impacts on fire-weather in south-east Australia" (PDF). CSIRO Marine and Atmospheric Research, Bushfire CRC and Australian Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 13 February 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Adair, Kieran (2010-02-17). "Firefighters warn of climate risk". Green Left Weekly. No. 826. p. 3. Retrieved 2010-02-19.

- ^ "Australias killer bushfires have their origins in Indian Ocean". Thaindian News. Retrieved 22 November 2009.

- ^ "Indian Ocean temperature link to bushfires". CSIRO. Retrieved November 22, 2009.

- ^ "Indian Ocean driving Australia's big dry: study". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 22 November 2009.

- ^ "Indian Ocean causes Big Dry: drought mystery solved". University of New South Wales, Faculty of Science. Retrieved 22 November 2009.

- ^ a b "Stay-at-home policy best, says NSW fire commissioner". The Australian. 9 February 2009. Retrieved 10 February 2009.

- ^ a b c d Rood, David (10 February 2009). "Forest strategies questioned". The Age. Retrieved 10 February 2009.

- ^ a b "Nixon defends fire policy". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 9 February 2009. Retrieved 10 February 2009.

- ^ a b "Tuckey points finger at parties". Sydney Morning Herald. 10 February 2009. Retrieved 10 February 2009.