Jun Tsuji: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

| era = [[20th century philosophy]] |

| era = [[20th century philosophy]] |

||

| school_tradition = [[Nihilism]], [[Individualist anarchism]], [[Dada]] |

| school_tradition = [[Nihilism]], [[Individualist anarchism]], [[Dada]] |

||

| main_interests = Creative Nothing, the ''Unmensch'', vagabondage, [[Dada]] as [[philosophy]], [[Japanese Buddhism]] |

| main_interests = Creative Nothing, the ''Unmensch'', vagabondage, [[Dada]] as [[philosophy]], [[Japanese Buddhism]] |

||

| influences = [[Max Stirner]], [[Kōtoku Shūsui]], Hirose Izen, [[Goethe]], [[Oscar Wilde]], [[Takahashi Shinkichi]] |

| influences = [[Max Stirner]], [[Kōtoku Shūsui]], Hirose Izen, [[Goethe]], [[Oscar Wilde]], [[Takahashi Shinkichi]] |

||

| influenced = [[Ito Noe]], [[Yoshiyuki Eisuke]], [[Hagiwara Kyōjiro]], [[Miyajima Sukeo]] |

| influenced = [[Ito Noe]], [[Yoshiyuki Eisuke]], [[Hagiwara Kyōjiro]], [[Miyajima Sukeo]] |

||

| Line 24: | Line 22: | ||

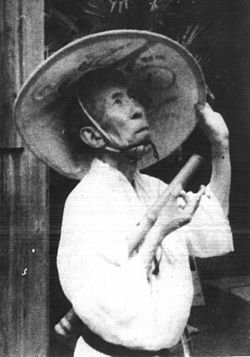

{{nihongo|'''Jun Tsuji''', later Ryūkitsu Mizushima |辻 潤|Tsuji Jun|extra=October 4, 1884 – November 24, 1944}} was a [[Japanese author]]: a [[poet]], [[essay]]ist, [[playwright]], and [[translator]]. He has also been described as a [[Dada|Dadaist]], [[nihilist]], [[epicurean]], [[shakuhachi]] [[music]]ian, [[actor]], [[translator]], [[feminist]], and [[bohemian]]. He [[translation|translated]] [[Max Stirner]]'s ''[[The Ego and Its Own]]'' and [[Cesare Lombroso]]'s ''The Man of Genius'' into [[Japanese language|Japanese]]. |

{{nihongo|'''Jun Tsuji''', later Ryūkitsu Mizushima |辻 潤|Tsuji Jun|extra=October 4, 1884 – November 24, 1944}} was a [[Japanese author]]: a [[poet]], [[essay]]ist, [[playwright]], and [[translator]]. He has also been described as a [[Dada|Dadaist]], [[nihilist]], [[epicurean]], [[shakuhachi]] [[music]]ian, [[actor]], [[translator]], [[feminist]], and [[bohemian]]. He [[translation|translated]] [[Max Stirner]]'s ''[[The Ego and Its Own]]'' and [[Cesare Lombroso]]'s ''The Man of Genius'' into [[Japanese language|Japanese]]. |

||

[[Tōkyō]]-born Tsuji Jun sought escape in literature from a childhood he described as "nothing but destitution, hardship, and a series of traumatizing difficulties".<ref>1982. Tsuji, Jun ed. Nobuaki Tamagawa. ''Tsuji Jun Zenshū'', v. 1. Tokyo: Gogatsushobo. 313.</ref> He became interested in [[Tolstoy]]an [[Humanism]], [[Kōtoku Shūsui]]'s [[socialist anarchism]], and the literature of [[Oscar Wilde]] and [[Voltaire]], among many others. Later, in 1920 Tsuji was introduced to Dada and became a self-proclaimed first Dadaist of Japan, a title also claimed by Tsuji's contemporary, [[Takahashi Shinkichi]] ([[:ja:高橋新吉|高橋 新吉]]). Tsuji became a fervent proponent of [[Stirnerite]] [[Egoist anarchism]], which would become a point of contention between himself and Takahashi. |

[[Tōkyō]]-born Tsuji Jun sought escape in literature from a childhood he described as "nothing but destitution, hardship, and a series of traumatizing difficulties".<ref>1982. Tsuji, Jun ed. Nobuaki Tamagawa. ''Tsuji Jun Zenshū'', v. 1. Tokyo: Gogatsushobo. 313.</ref> He became interested in [[Tolstoy]]an [[Humanism]], [[Kōtoku Shūsui]]'s [[socialist anarchism]], and the literature of [[Oscar Wilde]] and [[Voltaire]], among many others. Later, in 1920 Tsuji was introduced to Dada and became a self-proclaimed first Dadaist of Japan, a title also claimed by Tsuji's contemporary, [[Takahashi Shinkichi]] ([[:ja:高橋新吉|高橋 新吉]]). Tsuji became a fervent proponent of [[Stirnerite]] [[Egoist anarchism]], which would become a point of contention between himself and Takahashi. He wrote one of the prologues for famed [[feminist]] poet [[Hayashi Fumiko]]'s 1929 ''Ao Uma wo Mitari'' (『蒼馬を見たり』). |

||

Tsuji wrote during the 1920s, a dangerous period in Japanese history for controversial writers, during which he experienced the wages of censorship through police harassment and vicariously through the persecution of close associates such as his former wife, [[anarcho-feminist]] [[Ito Noe]], who was murdered in the [[Amakasu Incident]]. In 1932 Tsuji was institutionalized in a [[psychiatric hospital]] after what would become known as the "[[Tengu]] Incident". <ref>1932. “Tsuji Jun Shi Tengu ni Naru”, ''Yomiuri Shimbun'' (Newspaper), April 11th Morning Edition. </ref> He was diagnosed as having experienced a temporary psychosis probably resulting from his chronic [[alcoholism]]. Thereafter the once prolific Tsuji gave up his writing career, and he returned to his custom of vagabondage in the fashion of a [[Komusō]] [[monk]]. <ref>1949. ''Shinchō'', v. 80. Tokyo: Shinchōsha. 310.</ref> He is remembered for having helped found Dadaism in Japan along with contemporaries such as [[Murayama Tomoyoshi]], MAVO, [[Yoshiyuki Eisuke]], and [[Takahashi Shinkichi]]. Moreover, he was one of the most prominent Japanese contributors to Nihilist philosophy prior to [[World War II]]. Tsuji is now buried in Tokyo's Saifuku Temple. <ref>1971. Tamagawa, Nobuaki. ''Tsuji Jun Hyōden.'' Tōkyō: Sanʻichi Shobō. 335.</ref> He is also remembered as the father of prominent Japanese painter, Makoto Tsuji ([[:ja:辻まこと|辻 まこと]]). |

Tsuji wrote during the 1920s, a dangerous period in Japanese history for controversial writers, during which he experienced the wages of censorship through police harassment and vicariously through the persecution of close associates such as his former wife, [[anarcho-feminist]] [[Ito Noe]], who was murdered in the [[Amakasu Incident]]. In 1932 Tsuji was institutionalized in a [[psychiatric hospital]] after what would become known as the "[[Tengu]] Incident". <ref>1932. “Tsuji Jun Shi Tengu ni Naru”, ''Yomiuri Shimbun'' (Newspaper), April 11th Morning Edition. </ref> He was diagnosed as having experienced a temporary psychosis probably resulting from his chronic [[alcoholism]]. Thereafter the once prolific Tsuji gave up his writing career, and he returned to his custom of vagabondage in the fashion of a [[Komusō]] [[monk]]. <ref>1949. ''Shinchō'', v. 80. Tokyo: Shinchōsha. 310.</ref> He is remembered for having helped found Dadaism in Japan along with contemporaries such as [[Murayama Tomoyoshi]], MAVO, [[Yoshiyuki Eisuke]], and [[Takahashi Shinkichi]]. Moreover, he was one of the most prominent Japanese contributors to Nihilist philosophy prior to [[World War II]]. Tsuji is now buried in Tokyo's Saifuku Temple. <ref>1971. Tamagawa, Nobuaki. ''Tsuji Jun Hyōden.'' Tōkyō: Sanʻichi Shobō. 335.</ref> He is also remembered as the father of prominent Japanese painter, Makoto Tsuji ([[:ja:辻まこと|辻 まこと]]). |

||

Revision as of 23:46, 8 August 2010

Tsuji Jun Mizushima Ryūkitsu | |

|---|---|

Tsuji Jun | |

| Born | October 4, 1884 |

| Died | November 24, 1944 (aged 60) Tōkyō, Japan |

| Cause of death | Starvation |

| Occupation(s) | Dadaist, writer, and vagabond |

| Era | 20th century philosophy |

| Spouse | Ito Noe |

Jun Tsuji, later Ryūkitsu Mizushima (辻 潤, Tsuji Jun, October 4, 1884 – November 24, 1944) was a Japanese author: a poet, essayist, playwright, and translator. He has also been described as a Dadaist, nihilist, epicurean, shakuhachi musician, actor, translator, feminist, and bohemian. He translated Max Stirner's The Ego and Its Own and Cesare Lombroso's The Man of Genius into Japanese.

Tōkyō-born Tsuji Jun sought escape in literature from a childhood he described as "nothing but destitution, hardship, and a series of traumatizing difficulties".[1] He became interested in Tolstoyan Humanism, Kōtoku Shūsui's socialist anarchism, and the literature of Oscar Wilde and Voltaire, among many others. Later, in 1920 Tsuji was introduced to Dada and became a self-proclaimed first Dadaist of Japan, a title also claimed by Tsuji's contemporary, Takahashi Shinkichi (高橋 新吉). Tsuji became a fervent proponent of Stirnerite Egoist anarchism, which would become a point of contention between himself and Takahashi. He wrote one of the prologues for famed feminist poet Hayashi Fumiko's 1929 Ao Uma wo Mitari (『蒼馬を見たり』).

Tsuji wrote during the 1920s, a dangerous period in Japanese history for controversial writers, during which he experienced the wages of censorship through police harassment and vicariously through the persecution of close associates such as his former wife, anarcho-feminist Ito Noe, who was murdered in the Amakasu Incident. In 1932 Tsuji was institutionalized in a psychiatric hospital after what would become known as the "Tengu Incident". [2] He was diagnosed as having experienced a temporary psychosis probably resulting from his chronic alcoholism. Thereafter the once prolific Tsuji gave up his writing career, and he returned to his custom of vagabondage in the fashion of a Komusō monk. [3] He is remembered for having helped found Dadaism in Japan along with contemporaries such as Murayama Tomoyoshi, MAVO, Yoshiyuki Eisuke, and Takahashi Shinkichi. Moreover, he was one of the most prominent Japanese contributors to Nihilist philosophy prior to World War II. Tsuji is now buried in Tokyo's Saifuku Temple. [4] He is also remembered as the father of prominent Japanese painter, Makoto Tsuji (辻 まこと).

Tsuji was depicted in the 1969 film Eros Plus Massacre and has been the subject of several Japanese books and articles. Tsuji's friend and contemporary anarchist, Hagiwara Kyōjirō (萩原 恭次郎), described Tsuji as follows:

This person, “Tsuji Jun”, is the most interesting figure in Japan today... He is like a commandment-breaking monk, like Christ...

Vagrants and labourers of the town gather about him. The defeated unemployed and the penniless find in him their own home and religion... his disciples are the hungry and the poor of the world. Surrounded by these disciples he passionately preaches the Good News of Nihilism. But he is not Christlike, and he preaches but drunken nonsense. Then the disciples call him merely “Tsuji” without respect and sometimes hit him on the head. This is a strange religion...

But here Tsuji has regrettably been portrayed as a religious character. It sounds contradictory, but Tsuji is a religious man without a religion... As art is not a religion, neither is Tsuji's life religious. But in a sense it is... Tsuji calls himself an Unmensch... If Nietzsche's Zarathustra is religious... then Tsuji's teaching would be a better religion than Nietzsche's, for Tsuji lives in accord with his principles as himself...

Tsuji is a sacrifice of modern culture... In the Japanese literary world Tsuji can be considered a rebel. But this is not because he is a drunkard, nor because he lacks manners, nor because he is an anarchist. It is because he puts forth his dirty ironies as boldly as a bandit... Tsuji himself is very shy and timid in person... but his clarity and self-respect exposes the falsities of the famous in the literary world... [though] to many he really comes across as an anarchistic rogue...The literary world only sees him as having been born in this world to provide a source for gossip, but he is like Chaplin producing seeds of humour in their rumours... The common Japanese literati do not understand that the laugh of Chaplin is a contradictory tragedy... In a society of base, closed-minded people idealists are always taken as madmen or clowns.

Tsuji Jun is always drunk. If he doesn't drink he can't stand the suffering and sorrow of life. On the rare occasion he is sober... he does look the part of an incompetent and Unmensch-ian fool. Then his faithful disciples bring him saké in place of a ceremonial offering, pour electricity back into his robot heart, and wait for him to start moving... In this way the teaching of the Unmensch begins. It is a religion for the weak, the proletariat, the egoists, and those of broken personalities, and at the same time-- it is a most pure, a most sorrowful religion for modern intellectuals.External links

- Select e-texts of Tsuji's works. at Aozora bunko (Japanese)

- Tsuji Jun no Hibiki. (Japanese)

- ^ 1982. Tsuji, Jun ed. Nobuaki Tamagawa. Tsuji Jun Zenshū, v. 1. Tokyo: Gogatsushobo. 313.

- ^ 1932. “Tsuji Jun Shi Tengu ni Naru”, Yomiuri Shimbun (Newspaper), April 11th Morning Edition.

- ^ 1949. Shinchō, v. 80. Tokyo: Shinchōsha. 310.

- ^ 1971. Tamagawa, Nobuaki. Tsuji Jun Hyōden. Tōkyō: Sanʻichi Shobō. 335.

- ^ 1982. Tsuji, Jun ed. Nobuaki Tamagawa. Tsuji Jun Zenshū, v. 9. Tokyo: Gogatsushobo. 219-223.