French Foreign Legion: Difference between revisions

→English: suggests a more likely translation |

m →World War II: slightly better wording |

||

| Line 90: | Line 90: | ||

===World War II=== |

===World War II=== |

||

[[File:LEG 13DBLE 1942.jpg|thumb|left|100px|Uniform of the Légionnaires during the [[Battle of Bir Hakeim]] (1942).]] |

[[File:LEG 13DBLE 1942.jpg|thumb|left|100px|Uniform of the Légionnaires during the [[Battle of Bir Hakeim]] (1942).]] |

||

The Foreign Legion played a smaller role in [[World War II]], though having a part in the Norwegian, Syrian and North African campaigns. The [[13th Demi-Brigade]] was deployed in the [[Battle of Bir Hakeim]]. Reflecting the divided loyalties of the time, part of the Legion joined the [[Free French]] movement while another part served the [[Vichy France|Vichy]] government. A battle in the [[Syria-Lebanon campaign]] of June 1941 saw legionnaire fighting legionnaire as the 13th Demi-Brigade (D.B.L.E.) clashed with the 6th Régiment Etranger d'Infanterie at Damas in Syria. Later, 1,000 of the rank and file of the Vichy Legion unit joined the 13th D.B.L.E. of the Free French forces as a third battalion. Following the war, many former German soldiers joined the Legion to pursue a military career with an elite unit, an option that was no longer possible in Germany. |

The Foreign Legion played a smaller role in [[World War II]], though having a part in the Norwegian, Syrian and North African campaigns. The [[13th Demi-Brigade]] was deployed in the [[Battle of Bir Hakeim]]. Reflecting the divided loyalties of the time, part of the Legion joined the [[Free French]] movement while another part served the [[Vichy France|Vichy]] government. A battle in the [[Syria-Lebanon campaign]] of June 1941 saw legionnaire fighting legionnaire as the 13th Demi-Brigade (D.B.L.E.) clashed with the 6th Régiment Etranger d'Infanterie at Damas in Syria. Later, 1,000 of the rank and file of the Vichy Legion unit joined the 13th D.B.L.E. of the Free French forces as a third battalion. Following the war, many former German soldiers joined the Legion to pursue a military career with an elite unit, an option that was no longer possible in Germany. To this day, Germans constitute a strong presence in the Legion. |

||

===First Indochina War=== |

===First Indochina War=== |

||

Revision as of 20:43, 10 January 2011

| French Foreign Legion | |

|---|---|

The Legion emblem. | |

| Active | 10 March 1831—present |

| Country | France |

| Branch | French Army |

| Role | Military force |

| Size | c. 7,700 men in eleven regiments and one sub-unit |

| Garrison/HQ | Aubagne (Headquarters) Metropolitan France (5 regiments) French Guiana (3rd Infantry Regiment) Djibouti (13th Demi-Brigade) Mayotte (Detachment) |

| Motto(s) | "Legio Irus Actica" (The Legion is our Strength) "Legio Patria Nostra" (The Legion is our Motherland) |

| Colours | Red and green |

| March | Le Boudin |

| Anniversaries | Camerone Day (30 April) and Christmas[citation needed] |

| Commanders | |

| Current commander | Brigade General Alain Bouquin |

The French Foreign Legion (French: Légion étrangère) is a unique military unit in the French Army established in 1831. The legion was specifically created for foreign nationals wishing to serve in the French Armed Forces. Commanded by French officers, it is also open to French citizens, who amounted to 24% of the recruits as of 2007.[1]

The Legion is today known as an elite military unit whose training focuses not only on traditional military skills but also on its strong esprit de corps. As its men come from different countries with different cultures, this is a widely accepted solution to strengthen them enough to work as a team. Consequently, training is often described as not only physically challenging, but also extremely stressful psychologically.

History

The French Foreign Legion was created by Louis Philippe, the "King of the French", on 10 March 1831. The direct reason was that foreigners were forbidden to serve in the French Army after the 1830 July Revolution, so the Legion was created to allow the government a way around this restriction.[2] The purpose of the Legion was to remove disruptive elements from society and put them to use fighting the enemies of France. Recruits included failed revolutionaries from the rest of Europe, soldiers from the disbanded foreign regiments, and troublemakers in general, both foreign and French. Algeria was designated as the Legion's home.

In late 1831, the first Legionnaires landed in Algeria, the country that would be the Legion's homeland for 130 years and shape its character. The early years in Algeria were hard for Legionnaires because they were often sent to the worst postings, received the worst assignments and were generally uninterested in the new colony of the French.[3] The Legion's first service in Algeria came to an end after only four years, as it was needed elsewhere.

The Legion was primarily used to protect and expand the French colonial empire during the 19th century, but it also fought in almost all French wars including the Franco-Prussian War and both World Wars. The Foreign Legion has remained an important part of the French Army, surviving three Republics, The Second French Empire, two World Wars, the rise and fall of mass conscript armies, the dismantling of the French colonial empire and the French loss of the legion's base, Algeria.

Spain

To support Isabella's claim to the Spanish throne against her uncle, the French government decided to send the Legion to Spain. On 28 June 1835, the unit was handed over to the Spanish government. The Legion landed at Tarragona on 17 August with around 4,000 men who were quickly dubbed Los Argelinos (the Algerians) by locals because of their previous posting.

The Legion's commander immediately dissolved the national battalions to improve the esprit de corps. Later, he also created three squadrons of lancers and an artillery battery from the existing force to increase independence and flexibility. The Legion was dissolved on 8 December 1838, when it had dropped to only 500 men. The survivors returned to France, many reenlisting in the new Legion along with many of their former Carlist enemies.

Mexico

It was in Mexico on 30 April 1863 that the Legion earned its legendary status. A company led by Capitaine Danjou, numbering 62 soldiers and 3 officers, was escorting a convoy to the besieged city of Puebla when it was attacked and besieged by two thousand revolutionaries,[4] organised in three battalions of infantry and cavalry, numbering 1,200 and 800 respectively. The patrol was forced to make a defence in Hacienda Camarón, and despite the hopelessness of the situation, fought nearly to the last man. When only six survivors remained, out of ammunition, a bayonet charge was conducted in which three of the six were killed. The remaining three were brought before the Mexican general, who allowed them to return to France as an honour guard for the body of Capitaine Danjou. The captain had a wooden hand which was stolen during the battle; it was later returned to the Legion and is now kept in a case in the Foreign Legion museum at Aubagne, and paraded annually on Camerone Day. It is the Legion's most precious relic.

Franco-Prussian War

According to French law, the Legion was not to be used within Metropolitan France except in the case of a national invasion, and was consequently not a part of Napoleon III’s Imperial Army that capitulated at Sedan. With the defeat of the Imperial Army, the Second French Empire fell and the Third Republic was created.

The new Third Republic was desperately short of trained soldiers in the Franco-Prussian War, so the Legion was ordered to provide a contingent. On 11 October 1870 two provisional battalions disembarked at Toulon, the first time the Legion had been deployed in France itself. They attempted to lift the Siege of Paris by breaking through the German lines. They succeeded in re-taking Orléans, but failed to break the siege.

19th century colonial warfare

During the Third Republic, the Legion played a major role in French colonial expansion. They fought in North Africa (where they established their headquarters at Sidi Bel Abbès in Algeria), Benin, Madagascar, Indochina and Taiwan.

Tonkin campaign and Sino-French War

The Legion's 1st Battalion (Lieutenant-Colonel Donnier) was sent to Tonkin in the autumn of 1883, during the period of undeclared hostilities that preceded the Sino-French War (August 1884 to April 1885), and formed part of the attack column that stormed the western gate of Son Tay on 16 December. The 2nd and 3rd infantry battalions (chef de bataillon Diguet and Lieutenant-Colonel Schoeffer) were also deployed to Tonkin shortly afterwards, and were present in all the major campaigns of the Sino-French War. Two Legion companies led the defence at the celebrated Siege of Tuyen Quang (24 November 1884 to 3 March 1885). In January 1885 the Legion's 4th Battalion (chef de bataillon Vitalis) was deployed to the French bridgehead at Keelung (Jilong) in Formosa (Taiwan), where it took part in the later battles of the Keelung Campaign. The battalion played an important role in Colonel Jacques Duchesne's offensive in March 1885 that captured the key Chinese positions of La Table and Fort Bamboo and disengaged Keelung.

In December 1883, during a review of the 2nd Legion Battalion on the eve of its departure for Tonkin to take part in the Bac Ninh campaign, General François de Négrier pronounced a famous mot: Vous, légionnaires, vous êtes soldats pour mourir, et je vous envoie où l’on meurt! ('You, Legionnaires, you are soldiers in order to die, and I'm sending you to where one dies!')

World War I

In World War I, the Legion fought in many critical battles of the war, on the Western Front including Artois, Champagne, Somme, Aisne, Verdun (in 1917) and also suffered heavy casualties during 1918. The Legion was also in the Dardanelles and Macedonian front, and the Legion was highly decorated for its efforts. Many young foreigners, including Americans like Fred Zinn, volunteered for the Legion when the war broke out in 1914. There were marked differences between such idealistic volunteers as the poet Alan Seeger and the hardened mercenaries of the old Legion, making assimilation difficult. Nevertheless, the old and the new men of the Legion fought and died in vicious battles on the Western front, including Belloy-en-Santerre during the Battle of the Somme, where Seeger, after being mortally wounded by machine gun fire, cheered on the rest of his advancing battalion.[5]

As most European countries and the US were drawn into the War, many of the newer "duration only" volunteers who managed to survive the first years of the war were generally released from the Legion to join their respective national armies. Citizens of the Central Powers serving with the Legion on the outbreak of war were normally posted to garrisons in North Africa to avoid problems of divided loyalties.

Between the World Wars

In 1932, the Legion comprised 30,000 men in 6 multi-battalion regiments:

- 1st - Algeria and Syria

- 2d, 3d, and 4th - Morocco

- 5th - Indochina

- 1st Cavalry - Tunisia and Morocco.

World War II

The Foreign Legion played a smaller role in World War II, though having a part in the Norwegian, Syrian and North African campaigns. The 13th Demi-Brigade was deployed in the Battle of Bir Hakeim. Reflecting the divided loyalties of the time, part of the Legion joined the Free French movement while another part served the Vichy government. A battle in the Syria-Lebanon campaign of June 1941 saw legionnaire fighting legionnaire as the 13th Demi-Brigade (D.B.L.E.) clashed with the 6th Régiment Etranger d'Infanterie at Damas in Syria. Later, 1,000 of the rank and file of the Vichy Legion unit joined the 13th D.B.L.E. of the Free French forces as a third battalion. Following the war, many former German soldiers joined the Legion to pursue a military career with an elite unit, an option that was no longer possible in Germany. To this day, Germans constitute a strong presence in the Legion.

First Indochina War

During the First Indochina War (1946–54), the Legion saw its numbers swell due to the incorporation of Second World War veterans that couldn't adapt to civilian life. Even so, although the Legion distinguished itself, it also took a heavy toll during the war: constantly being deployed in operations, it even reached the point that whole units were annihilated in combat, in what was a traditional Legion battlefield. Units of the Legion were also involved in the defence of Dien Bien Phu and lost a large number of men in the battle.

Algerian War

The Algerian War of Independence (1954–62) was a highly-traumatic conflict for the Legion. Constantly on call throughout the country, heavily engaged in fighting against the National Liberation Front and the Armée de Libération Nationale (ALN), the war brought the Legion to the brink of extinction after some officers, men and the highly-decorated 1st Foreign Parachute Regiment took part in the Generals' putsch. Notable operations included the Suez Crisis, the Battle of Algiers and various offensives launched by General Maurice Challe including Operations Oranie and Jumelles.

Post-colonial Africa

By 1962 the morale of the Legion was at an all-time low; it had lost its traditional and spiritual home (Algeria), elite units had been disbanded, in addition, many officers and men were arrested or deserted to escape persecution. General deGaulle considered disbanding it altogether. But after downsizing it to 8,000 men, stripping it of all heavy weaponry, the Legion was spared, packed up and re-headquartered in metropolitan France.[6]

The Legion now had a new role as a rapid intervention force to preserve French interests not only in its former African colonies but in other nations as well; it was also a return to its roots of being a unit always ready to be sent to hot-spots all around the world. Some notable operations include: the Chadian-Libyan conflict in 1969-72 (the first time that the Legion was sent in operations after the Algerian War), 1978–79, and 1983–87; Kolwezi in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo in May 1978; Rwanda in 1990-94; and the Côte d'Ivoire (the Ivory Coast) in 2002 to the present.

1962–1991

- 1969–1971: interventions in Chad

- 1978 : Battle of Kolwezi (Zaïre)

Gulf War

In September 1990, the 1e REC, the 2e REI, and the 6e REG were sent to the Persian Gulf as a part of Opération Daguet. They were a part of the French 6th Light Armoured Division, whose mission was to protect the coalition's left flank. After a four-week air campaign, coalition forces launched the ground campaign. It quickly penetrated deep into Iraq, with the Legion taking the Al Salman airport, meeting little resistance. The war ended after a hundred hours of fighting on the ground, which resulted in very light casualties for the Legion.

1991-Present

- 1991 : Evacuation of French citizens and foreigners in Rwanda, Gabon and Zaire.

- 1992 : Cambodia and Somalia

- 1993 : Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina

- 1995 : Rwanda

- 1996 : Central African Republic

- 1997 : Congo-Brazzaville

- Since 2001 : Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan

- 2002-2003 : Operation Licorne in Côte d’Ivoire

- 2008 : EUFOR Tchad/RCA in Chad.

Membership

Open to people of any nationality, most Legionnaires still come from European countries but a growing percentage comes from Latin America, 24%. Most of the Legion's commissioned officers are French with approximately 10% being former Legionnaires who have risen through the ranks.

Membership of the Legion is often a reflection of political shifts: specific national representations generally surge whenever a country has a political crisis and tend to subside once the crisis is over and the flow of recruits dries up. After the First World War, many (Tsarist) Russians joined. Immediately before the Second World War, Czechs, Poles and Jews from Eastern Europe fled to France and ended up enlisting in the Legion. Following the break-up of Yugoslavia, there were many Serbian nationals. Also in the 1990s, the collapse of the Soviet Union, and the changes in the former Warsaw Pact countries, led to an increase in recruitment from Poland and from the former republics of the USSR.

In addition to the fluctuating numbers of political refugees, asylum seekers and economic migrants from a wide variety of nations, there has been, since the end of World War Two, a strong core from Germany and Britain. The Legion appears to have become as much a part of these two nations' culture as a French institution, and a certain stability in recruitment levels has developed.

During the late 1980s, the Legion saw a large intake of trained soldiers from the UK. These men had left the British Army following its restructuring and the Legion's parachute unit was a popular destination. At one point, the famous 2eme REP had such a large number of British citizens amongst the ranks that it was a standing joke that the unit was really called '2eme PARA', a reference to the 2nd Battalion, the Parachute Regiment of the British Army.

While no serious studies have been made of the motives for enlistment over the years, the majority in the Legion's ranks were either those transient souls in need of escape and a regular wage, or refugees from countries undergoing crises. In recent years, the improved conditions and professionalism of the Legion have in turn attracted a new kind of 'vocational' recruit, from middle-class backgrounds in stable and prosperous countries, such as the US, Britain and France itself.

In the past, the Legion had a reputation for attracting criminals on the run and would-be mercenaries, but the admissions process is now severely restricted and background checks are performed on all applicants. Generally speaking, convicted felons are prohibited from joining the service. Legionnaires must enlist under a pseudonym ("declared identity"). This disposition exists in order to allow people who want to start their lives over to enlist. French citizens can enlist under a declared, fictitious, foreign citizenship (generally, a francophone one, often that of Canada or Monaco). After one year's service, Legionnaires can regularise their situation under their true identity. After serving in the Legion for three years, a legionnaire may apply for French citizenship.[7] He must be serving under his real name, must no longer have problems with the authorities, and must have served with “honour and fidelity”. Furthermore, a soldier who becomes injured during a battle for France can apply for French citizenship under a provision known as “Français par le sang versé” ("French by spilled blood").

Officially, there has been only one woman member, Briton Susan Travers who joined Free French Forces during the Second World War and became a member of the Legion after the war, serving in Vietnam during the First Indochina War.[8] The Foreign Legion will, on occasion, induct honourary members into its ranks. During the siege of Dien Bien Phu this honour was granted to General Christian de Castries, Colonel Pierre Langlais, Geneviève de Galard ("The Angel of Dien Bien Phu") and Marcel Bigeard, the OIC of the 6th BPC. Norman Schwarzkopf is also an honorary member.

Ranks

Soldats du rang (Ordinary Legionnaires)

All volunteers in the French Foreign Legion begin their careers as basic legionnaires with one in four eventually becoming a Sous-Officier (NCO).

^ †: No further promotions are given on attaining the rank of Caporal Chef.

Table note: Command insignia in the Legion use gold indicating Foot Arms in the French Army. But the Légion étrangère service color is green not red (Infantry), as shown.

Sous-Officiers (Non-commissioned Officers)

Sous-officiers (NCOs) account for 25% of the current legion's total manpower.

| Legion rank | Equivalent rank | Period of service | Insignia |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sergent | Sergeant | After 3 years of service. | |

| Sergent Chef | Senior Sergeant | After 3 years as Sergent and between 7 to 14 years of service. | |

| Adjudant | Warrant Officer | After 3 years as Sergent Chef. | |

| Adjudant Chef | Senior Warrant Officer | After 4 years as Adjutant and at least 14 years service. | |

| Major ‡ | Regimental Sergeant Major | Appointment by either: (i) passing an examination (ii). promotion after a minimum of 14 years service without an examination. |

^ ‡: Since 1st January 2009, the French military rank of Major has been attached to the Sous-officiers. Prior to this, Major was an independent rank between NCOs and commissioned officers. It is an executive position within a regiment or demi-brigade responsible for senior administration, standards and discipline.

Officiers (Officers)

Most officers are seconded from the French Army, though roughly 10% are former NCOs promoted from the ranks of la Légion.

| Legion rank | Equivalent rank | Command responsibility | Insignia |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aspirant | Cadet | - | |

| Sous-Lieutenant | Second Lieutenant | Junior section leader | |

| Lieutenant | First Lieutenant | A section. | |

| Capitaine | Captain | A company. | |

| Commandant | Major | A battalion. | |

| Lieutenant-Colonel | Lieutenant-Colonel | Junior régiment or demi-brigade leader. | |

| Colonel | Colonel | A régiment or demi-brigade . | |

| Général de Brigade | Brigadier General | Entire French Foreign Legion |

Traditions

As the Legion is composed of soldiers of different nationalities and backgrounds, it needed to develop an intense Esprit de Corps which is carried out by the development of camaraderie, specific traditions, the high sense of loyalty of its légionnaires, the quality of their training and the pride of being a soldier of an élite unit.

Code of Honour

Every Legionnaire must know by heart the "Legionnaire's Code of Honour". The Legionnaires spend many hours learning it, reciting it, and then getting the vocal synchronisation together:

| French | English |

|---|---|

|

|

Mottoes

Honneur et Fidélité

Unlike any other French unit, the motto of the Legion's regimental flags is not Honneur et Patrie (Honour and Motherland) but Honneur et Fidélité (Honour and Fidelity).

Legio Patria Nostra

| « Legio Patria Nostra » |

Legio Patria Nostra (The Legion is our Fatherland) is the motto of the Legion. The adoption of the Legion as a new fatherland does not imply the repudiation by the légionnaire of his first nationality. The French Foreign Legion respects the original fatherland of the légionnaires who are totally free to preserve their nationalities. The Legion even asks the agreement of any légionnaire who could be sent in a military operation where his country of origin would be committed

Regimental mottoes

- 2nd REP : More Majorum (According to the traditions of our ancestors)

- 3rd REI : Legio Patria Nostra

- 13th DBLE : More Majorum

- 2nd REI : Être prêt (Be ready)

- DLEM : Pericula ludus (Danger is my pleasure)

- 1st REC : Nec pluribus impar (No other equal)

- 1st REG : Ad unum (To the end)

- 2nd REG : Rien n'empêche (Nothing prevents)

Pionniers of the Legion

The Pionniers (pioneers) are the combat engineers and a traditional unit of the Legion. The sapeurs traditionally sport large beards, wear leather aprons and gloves and hold axes. The sappers were very common in the French army and in other European armies during the Napoleonic era but progressively disappeared in the 19th century, except in the Legion.

In the French Army, since the 18th century, every grenadier battalion had a small unit of sappers. They had the mission to advance, under the enemy's fire, in order to destroy with their axes the obstacles drawn by the enemy and to clear the way for the rest of the infantry. The danger of such missions and their short life expectancies, allowed them certain privileges, such as the authorization to wear beards.

The current pioneer unit of the Legion reintroduced the symbols of the Napoleonic sappers: the beard, the axe, the leather apron, the crossed-axes insignia and the leather gloves. If the parades of the Legion are opened by this unit, it is to commemorate the traditional role of the sappers "opening the way" for the troops.

Marching step

Also notable is the marching pace of the Legion. In comparison to the 120-step-per-minute pace of other French units, the Legion has an 88-step-per-minute marching speed. It is also referred to by Legionnaires as the "crawl." This can be seen at ceremonial parades and public displays attended by the Legion, particularly while parading in Paris on 14 July (Bastille Day Military Parade). Because of the impressively slow pace, the Legion is always the last unit marching in any parade. The Legion is normally accompanied by its own band which traditionally plays the march of any one of the regiments comprising the Legion, except that of the unit actually on parade. The regimental song of each unit and "Le Boudin" is sung by Legionnaires standing at attention. Also, because the Legion must always stay together, it does not break formation into two when approaching the presidential grandstand, as other French military units do, in order to preserve the unity of the Legion.

Contrary to popular belief, the adoption of the Legion's slow marching speed was not due to a need to preserve energy and fluids during long marches under the hot Algerian sun. Its exact origins are somewhat unclear, but the official explanation is that although the pace regulation does not seem to have been instituted before 1945, it hails back to the slow, majestic marching pace of the Ancien Régime, and its reintroduction was a "return to traditional roots".[9] This was in fact, the march step of the Legion's ancestor units - the Régiments Étrangers or Foreign Regiments of the Ancien Régime French Army, the Grande Armée's foreign units, and the pre-1831 foreign regiments.

"Le boudin"

"Le Boudin" is the French Foreign Legion's marching song.

Chorus

Tiens, voilà du boudin, voilà du boudin, voilà du boudin

Pour les Alsaciens, les Suisses et les Lorrains,

Pour les Belges y'en a plus (bis)

Ce sont des tireurs au cul

Pour les Belges y'en a plus (bis)

Ce sont des tireurs au cul.

Bridge I

Nous sommes des dégourdis, nous sommes des lascars,

Des types pas ordinaires,

Nous avons souvent notre cafard,

Nous sommes des Légionnaires.

1

Au Tonkin, la Légion immortelle

A Tuyen-Quang illustra notre Drapeau.

Héros de Camerone et frères modèles

Dormez en paix dans vos tombeaux.

Bridge II

Nos anciens ont su mourir

Pour la Gloire de la Légion,

Nous saurons bien tous périr

Suivant la tradition.

2

Au cours de nos campagnes lointaines,

Affrontant la fièvre et le feu,

Nous oublions avec nos peines

La mort qui nous oublie si peu

Nous, la Légion.

English

Chorus

Here you are, some blood pudding, some blood pudding, some blood pudding

for the Alsatians, Swiss and Lorrains

For the Belgians, There's none left (2x)

They're lazy shirkers (Repeat last two lines)

Bridge 1

We're always at ease, we're rough and tough, no ordinary guys

We've often got our black moods, for we are Legionnaires

1

In Tonkin, the Legion immortal

At Tuyen Quiang our flag we honored

Heroes of Camerone and model brothers, sleep at peace in your tombs

Bridge 2

Our ancestors died, for the Legion's glory

We will soon all perish according to tradition

2

During our far-off campaigns, facing fever and fire

Our sadnesses we forget with

Death's which so little we forget, for we are the Legion

Other marches

|

|

Composition

Previously, the Légion was not stationed in mainland France except in wartime. Until 1962, the Legion headquarters were located in Sidi Bel Abbès, Algeria. Nowadays, some units of the Légion are in Corsica or overseas possessions ( mainly in French Guiana , guarding Guiana Space Center ), while the rest are in the south of mainland France. Current headquarters are in Aubagne, France, just outside Marseille.

- Mainland France

- 1st Foreign Cavalry Regiment (1e REC), based in Orange, Vaucluse (armoured troops)

- 1st Foreign Engineer Regiment (1e REG), based in Laudun

- 1st Foreign Regiment (1e RE), based in Aubagne

- 2nd Foreign Engineer Regiment (2e REG), based in St Christol

- 2nd Foreign Infantry Regiment (2e REI), based in Nîmes

- 4th Foreign Regiment (4e RE), based in Castelnaudary (training)

- Corsica

- 2nd Foreign Parachute Regiment (2e REP), based in Calvi, Corsica

- French Overseas Territories and Overseas Collectives

- 3rd Foreign Infantry Regiment (3e REI), based in French Guiana

- Foreign Legion Detachment in Mayotte (DLEM)

- Africa

- 13th Foreign Legion Demi-Brigade (13 DBLE), based in Djibouti.

-

COMLE -

1er RE -

1er REC -

1er REG -

2e REI -

2e REG -

2e REP -

3e REI -

4e RE -

13e DBLE -

DLEM -

GRLE

Disbanded unit and attempted coup

The 1st Foreign Parachute Regiment (1e Régiment Étranger Parachutiste, 1e REP) was established in 1955 during the Algerian War and disbanded in April 1961 as the entire regiment rose against the French government of Charles de Gaulle (Algiers Putsch), in protest against moves to negotiate an end to the Algerian War and providing Algeria's independence from France.

Following the independence of Algeria in 1962, the Legion was reduced in numbers but not disbanded, unlike most other units comprising the Armée d’Afrique: Zouaves, Tirailleurs, Meharistes, Harkis, Goums, Chasseurs d'Afrique and all but one of the Spahi regiments. The effect was to retain the Foreign Legion as a professional force which could be used for military interventions outside France and not involve the politically unpopular use of French conscripts. The subsequent abolition of conscription in France in 2001 and the creation of an entirely professional army might be expected to put the Legion's long-term future at risk but as of 2009 this has not been the case.

Current deployments

These deployments are current as of December 2008:[10]

Note: English names for countries or territories are in parentheses.

- Opérations extérieures (other than at home bases or on standard duties)

- Guyane (French Guiana) Mission de presence sur l’Oyapok - Protection - 3e REI Protection CSG ; 2e REP / CEA; 2e REI / 4° compagnie

- Afghanistan Intervention 1e REC / 3° escadron (1 peloton); 2e REI / 4° compagnie OMLT; 2e REG / 1ère compagnie

- Mayotte (Departmental Collectivity of Mayotte) Prevention DLEM Mission de souveraineté

- Djibouti Prevention 13 DBLE; 1e REC / 1° escadron; 1e REG / 3° compagnie

- Gabon Prevention 2e REP / 3° compagnie - 4° compagnie

| Acronym | French Name | English Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| CEA | Compagnie d'éclairage et d'appuis | Reconnaissance and Support Company |

| CAC | Compagnie anti-char | Anti-Tank Company |

| UCL | Unité de commandement et de logistique | Unit of Command and Logistics |

| EMT | État-major tactique | Tactical Command Post |

| NEDEX | Neutralisation des explosifs | Neutralisation and Destruction of Explosives |

| OMLT | Operational Monitoring and Liaison Team (The official name for this branch is in English) | |

Recruitment process

| First Day | In a Legion Information Center. Reception, Information, and Terms of contract |

| Pre-selection | 1 to 3 days in a Legion Recruitment Center (Paris - Aubagne). Confirmation of motivation, initial medical check-up, finalising enlistment papers and signing of 5-year service contract. |

| Selection | 1 to 10 days in the Recruitment and Selection Center in Aubagne. Psychological and personality tests, logic tests (no education requirements), medical exam, physical condition tests, motivation and security interviews. Confirmation or denial of selection. |

| Final Selection | 7 days: Signing and handing-over of the five-year service contract. Incorporation into the Legion as a trainee. |

Legion basic training

Basic training is conducted in the 4th Foreign Regiment with a duration of 15 weeks:

- Initial training of 4 weeks - initiation to military lifestyle; outdoor and field activities; learning legion traditions, learning French language.

- March "Képi Blanc" and graduation ceremony - 1 week.

- Technical and practical training (alternating with barracks and field training) - 3 weeks.

- Mountain training (Chalet at Formiguière in the French Pyrenees) - 1 week.

- Technical and practical training (alternating barracks and field training) - 2 weeks.

- Examinations and obtaining of the elementary technical certificate (CTE) - 1 week.

- March ending basic training - 1 week.

- Light vehicle / trucks school - 1 week.

- Return to Aubagne before reporting to the assigned regiment - 1 week.

Recruitment chart

The following is a chart showing the national origin of the more than 600,000 Legionaries of the force from 1831 to 1961, which was compiled in 1963. It should be noted that, at a given moment, principal original nationalities of the foreign legion reflect the events in history at the time they join. The legion allows men to escape from the worries of war, especially if their native country has lost. The large numbers of Germans joining in the wake of WWII led to the misconception that the Legion was full of former Waffen SS and Wehrmacht personnel. It is not surprising to see that a large number of German enlistments in the period following WWII, but the figures do not show whether or not the post-WWI period had a similar boost. Bernard B. Fall, who was a supporter of the French government, writing in the context of the First Indochina War, has called the notion that the Foreign Legion was mainly German at that time:

"a canard . . . with the sub variant that all those Germans were at least SS generals and other much wanted war criminals. As a rule, and in order to prevent any particular nation from making the Legion into a Praetorian guard, any particular national component is kept at about 25 percent of the total. Even supposing (and this was the case, of course) that the French recruiters, in the eagerness for candidates would sign up Germans enlisting as Swiss, Austrian, Scandinavian and other nationalities of related ethnic background, it is unlikely that the number of Germans in the Foreign Legion ever exceeded 35 percent. Thus, without making an allowance for losses, rotation, discharges, etc., the maximum number of Germans fighting in Indochina at any one time reached perhaps 7 000 out of 278 000. As to the ex-Nazis, the early arrivals contained a number of them, none of whom were known to be war criminals. French Intelligence saw to that.

Since, in view of the rugged Indochinese climate, older men without previous tropical experience constituted more a liability than an asset, the average age of the Legion enlistees was about 23. At the time of the battle of Dien Bien Phu, any Legionnaire of that age group was at the worst, in his "Hitler Youth" shorts when the [Third] Reich collapsed.[11]

.

When looking at the overall recruitment chart, one must keep in mind that the Legion accepts people enlisting under a nationality that is not their own. The large number of Swiss and Belgians are actually more likely than not Frenchmen who wish to avoid detection.[12] In addition many Alsatians are said to have joined the Legion when Alsace was part of the German Empire, and may have been recorded as German while considering themselves French.

| Rank | Country of origin | Total numbers |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 210,000 | |

| 2 | 60,000 | |

| 3 | 50,000 | |

| 4 | 50,000 | |

| 5 | 40,000 | |

| 6 | 30,000 | |

| 7 | 10,000 | |

| 8 | 6,000 | |

| 9 | 5,000 | |

| 10 | 4,000 | |

| 11 | 4,000 | |

| 12 | 4,000 | |

| 13 | 3,000 | |

| 14 | 3,000 | |

| 15 | 2,300 | |

| 16 | 1,500 | |

| 17 | 1,500 | |

| 18 | 1,300 | |

| 19 | 1,000 | |

| 20 | 1,000 | |

| 21 | 700 | |

| 22 | 500 | |

| 23 | 500 | |

| 24 | 500 | |

| 25 | 500 | |

| 26 | 200 | |

| 27 | 200 | |

| 28 | 200 | |

| 29 | 100 | |

| 30 | 100 | |

| 31 | 100 | |

| 32 | 100 | |

| 33 | 100 | |

| 34 | 100 | |

| 35 | 100 | |

| 36 | 100 | |

| 37 | 65 | |

| 38 | 25 |

Regarding recruitment conditions within the Foreign Legion, please see the official page (in English) dedicated to the subject:.[13] With regard to age limits, recruits can be accepted from ages ranging from 17 ½ (with parental consent) to 40 years old.

Uniforms

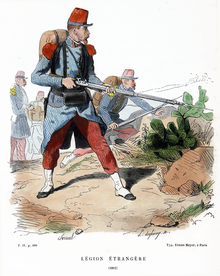

From its foundation until World War I the Legion normally wore the uniform of the French line infantry for parade with a few special distinctions. The field uniform was often modified under the influence of the extremes of climate and terrain in which the Legion served. Shakos were soon replaced by the light cloth kepi which was far more suitable for North African conditions. The practice of wearing heavy capotes (greatcoats) on the march and vestes (short hip-length jackets) as working dress in barracks was followed by the Legion from its establishment.[14]

One short lived aberration was the wearing of green uniforms in 1856 by Legion units recruited in Switzerland for service in the Crimean War. In the Crimea itself (1854–59) a hooded coat and red or blue waist sashes were adopted for winter dress, while during the Mexican Intervention (1863–65) straw hats or sombreros were sometimes substituted for the kepi. When the latter was worn it was usually covered with a white "havelock" - the predecessor of the white kepi that was to become a symbol of the Legion. Legion units serving in France during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71 were distinguishable only by minor details of insignia from the bulk of the French infantry. However subsequent colonial campaigns saw an increasing use of special garments for hot weather wear such as collarless keo blouses in Tonkin 1884-85, khaki drill jackets in Dahomey (1892) and drab covered topees worn with all-white fatigue dress in Madagascar (1895).[15]

In the early 20th century the Legionnaire wore a red kepi with blue band and piping, dark blue tunic with red collar, red cuff patches, and red trousers. The most distinctive features were the green epaulettes (replacing the red of the line) worn with red woollen fringes; plus the embroidered Legion badge of a red flaming grenade, worn on the kepi front instead of a regimental number. In the field a light khaki cover was worn over the kepi, sometimes with a protective neck curtain attached. The standard medium-blue double breasted greatcoat (capote) of the French infantry was worn, usually buttoned back to free the legs for marching. Around the waist was a broad blue sash, copied from that of the Zouaves. The blue sash provided warmth and support as well as (supposedly) preventing intestinal diseases. White linen trousers tucked into short leather leggings were substituted for red serge in hot weather. This was the origin of the "Beau Geste" image of the Legion.

In barracks a white bleached kepi cover was often worn together with a short dark blue jacket ("veste") or white blouse plus white trousers. The original kepi cover was khaki and due to constant washing turned white quickly. The white or khaki kepi cover was not unique to the Legion at this stage but was commonly seen amongst other French units in North Africa. It later became particularly identified with the Foreign Legion as the unit most likely to serve at remote frontier posts (other than locally recruited tirailleurs who wore fezzes or turbans). The variances of climate in North Africa led the French Army to the sensible expedient of letting local commanders decide on the appropriate "tenue de jour" (uniform of the day) according to circumstances. Thus a Legionnaire might parade or walk out in blue tunic and white trousers in hot weather, blue tunic and red trousers in normal temperatures or wear the blue greatcoat with red trousers under colder conditions. The sash could be worn with greatcoat, blouse or veste but not with the tunic. Epaulettes were a detachable dress item worn only with tunic or greatcoat for parade or off duty wear.

Officers wore the same dark blue (almost black) tunics as those of their colleagues in the French line regiments, except that black replaced red as a facing colour on collar and cuffs. Gold fringed epaulettes were worn for full dress and rank was shown by the number of gold rings on both kepi and cuffs. Trousers were red with black stripes or white according to occasion or conditions. All-white or light khaki uniforms (from as early as the 1890s) were often worn in the field or for ordinary duties in barracks. Non-commissioned officers were distinguished by red or gold diagonal stripes on the lower sleeves of tunics, vestes and greatcoats. Small detachable stripes were buttoned on to the front of the white shirt-like blouse.

Prior to 1914 units in Indo-China wore white or khaki Colonial Infantry uniforms with Legion insignia, to overcome supply difficulties. This dress included a white sun helmet of a model that was also worn by Legion units serving in the outposts of Southern Algeria, though never popular with the wearers. During the initial months of World War I Legion units serving in France wore the standard blue greatcoat and red trousers of the French line infantry, distinguished only by collar patches of the same blue as the capote, instead of red. After a short period in sky-blue the Legion adopted khaki with steel helmets, from early 1916. A mustard shade of khaki drill had been worn on active service in Morocco from 1909, replacing the classic blue and white. The latter continued to be worn in the relatively peaceful conditions of Algeria throughout World War I, although increasingly replaced by khaki drill. The pre-1914 blue and red uniforms could still be occasionally seen as garrison dress in Algeria until stocks were used up about 1919.

During the early 1920s plain khaki drill uniforms of a standard pattern became universal issue for the Legion with only the red and blue kepi (with or without a cover) and green collar braiding to distinguish the Legionnaire from other French soldiers serving in North African and Indo-China. The neck curtain ceased to be worn from about 1915, although it survived in the newly raised Foreign Legion Cavalry Regiment into the 1920s. The white blouse (bourgeron) and trousers dating from 1882 were retained for fatigue wear until the 1930s.

At the time of the Legion's centennial in 1931, a number of traditional features were reintroduced at the initiative of the then commander Colonel Rollet. These included the blue sash and green/red epaulettes. In 1939 the white covered kepi won recognition as the official headdress of the Legion to be worn on most occasions, rather than simply as a means of reflecting heat and protecting the blue and red material underneath. The 3rd REI adopted white tunics and trousers for walking out dress during the 1930s and all Legion officers were required to obtain full dress uniforms in the pre-war colours of black and red from 1932 to 1939.

During World War II the Legion wore a wide range of uniform styles depending on supply sources. These ranged from the heavy capotes and Adrian helmets of 1940 through to British battledress and US field uniforms from 1943 to 1945. The white kepi was stubbornly retained whenever possible.

The white kepis, together with the sash and epaulettes survive in the Legion's modern parade dress. Since the 1990s the modern kepi has been made wholly of white material rather than simply worn with a white cover. Officers and senior NCOs still wear their kepis in the pre-1939 colours of dark blue and red. A green tie and (for officers) a green waistcoat recall the traditional branch colour of the Legion. From 1959 a green beret became the ordinary duty headdress of the Legion, with the kepi reserved for parade and off duty wear. Other items of dress are the standard issue of the French Army. Officers seconded to the Foreign Legion reportedly retain one Legion button on the vests of their dress uniforms upon returning to their original regiments.

Equipment

The Foreign Legion is basically equipped with the same equipment as similar units elsewhere in the French Army. These include:

- The FAMAS assault rifle, a French-made automatic bullpup-style rifle, most of which were designed for the 5.56x45mm NATO round. In bullpup-style firearms, the action and magazine are located behind the trigger which increases the barrel length relative to the overall weapon length. This permits shorter weapons for the same barrel length, saves weight and improves ease of handling.

References in popular culture

Beyond its reputation as an elite unit often engaged in serious fighting, the recruitment practices of the French Foreign Legion have also led to a romantic view of it being a place for a wronged man to leave behind his old life to start a new one, yet also full of scoundrels and men escaping justice.

Emulation by other countries

Spanish Legion

The Spanish Legion was created in 1920, in emulation of the French one, and had a significant role in Spain's colonial wars in Morocco and in the Spanish Civil War on the Nationalist side. Unlike its French model, the number of non-Spanish recruits never exceeded 25%, most of these from Latin America. It now only recruits Spanish nationals.

Israeli Mahal

In Israel, Mahal (Hebrew: מח"ל, an acronym for Mitnadvei Hutz LaAretz which means Volunteers from outside the Land[of Israel]) is a term designating non-Israelis serving in the Israeli military. The term originates with the (approximately) 4,000 both Jewish and non-Jewish volunteers who went to Israel to fight in the 1948 Arab-Israeli War including Aliyah Bet.[16] The original Mahalniks were mostly World War II veterans from American and British armed forces.

Today, there is a department within the Israeli Ministry of Defense which administers the enlistment of non-Israeli citizens in the country's armed forces.

Netherlands KNIL Army

Though not named "Foreign Legion", the Dutch Koninklijk Nederlandsch-Indische Leger (KNIL), or Royal Netherlands-Indian Army (in reference to the Dutch East Indies, now Indonesia), was created in 1830, a year before the French legion, and is therefore not an emulation but an entirely original idea and had a similar recruitment policy. It stopped being a foreign legion around 1900 when recruitment was restricted to Dutch citizens and to the indigenous peoples of the Dutch East Indies. The KNIL was finally disbanded on 26 July 1950, seven months after the Netherlands formally recognised Indonesia as a sovereign state, and almost five years after Indonesia declared its independence.

See also

- Régiments de marche de volontaires étrangers

- List of Foreign Legionnaires

- Foreign legion

- Spanish Legion

- International Legion

- Memorial to the American Volunteers, Paris

- Lafayette Escadrille

Notes

References

- ^ Jean-Dominique Merchet, La Légion s'accroche à ses effectifs

- ^ Porch p. 2-4

- ^ Porch p. 17-18

- ^ "About the Legion". Retrieved 9 March 2007.

- ^ Shortly before his death, Seeger wrote, "I have a rendez-vous with Death, at some disputed barricade...And I to my pledged word am true, I shall not fail that rendevous."

- ^ http://www.legionofthelost.com/gallery.html

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions About the Legion (French)". Retrieved 10 September 2008.

- ^ http://www.amazon.com/Tomorrow-Be-Brave-Memoir-Foreign/dp/0743200020/

- ^ Szecsko, P.17

- ^ http://www.legion-etrangere.info/index.php?post/2008/12/D%C3%A9cembre-2008

- ^ Bernard B. Fall, Street Without Joy, pp. 279-280

- ^ Evan McGorman, Life in the French Foreign Legion, p. 21

- ^ http://www.legion-recrute.com/en/condition.php

- ^ Martin Windrow, page 16 "Uniforms of the French Foreign Legion, ISBN 0 7137 1010 1

- ^ Martin Windrow, pages 26-56 "Uniforms of the French Foreign Legion, ISBN 0 7137 1010 1

- ^ Benny Morris, 1948, 2008, p.85.

Bibliography

- Geraghty, Tony. March or Die: A New History of the French Foreign Legion, 1987, ISBN 0-8160-1794-8

- McGorman, Evan. Life in the French Foreign Legion: How to Join and What to Expect When You Get There. Hellgate Press, 2000. ISBN 1-55571-633-4

- Porch, Douglas. The French Foreign Legion. New York: Harper Collins, 1991. ISBN 0-06-092308-3

- The French Foreign Legion in Kolwezi Roger Rousseau, 2006. ISBN 2-9526927-1-8

- Szecsko, Tibor. Le Grand Livre des Insignes de la Légion Etrangère. Aubagne, I.I.L.E / S.I.H.L.E, 1991. ISBN 2-9505938-0-1

External links

- Official Website

- Official Recruitment Office of the Foreign Legion

- Le Musée de la Légion étrangère (legion museum)

- French Foreign Legion forum

- Photo gallery: Training with the French Foreign

- Website about french Daguet Division (First Gulf War 1990-1991)

- Books

- In the Foreign Legion (1910) - by Erwin Rosen (b. 1876)

- Books about the Foreign Legion 1905-1992

- [1]