Secular humanism: Difference between revisions

ClueBot NG (talk | contribs) m Reverting possible vandalism by 203.82.80.100 to version by 174.111.21.235. False positive? Report it. Thanks, ClueBot NG. (192806) (Bot) |

|||

| Line 252: | Line 252: | ||

*[[Secularism]] |

*[[Secularism]] |

||

*[[Transhumanism]] |

*[[Transhumanism]] |

||

*[[Naturalistic pantheism]] |

|||

==Further reading== |

==Further reading== |

||

Revision as of 23:45, 16 January 2011

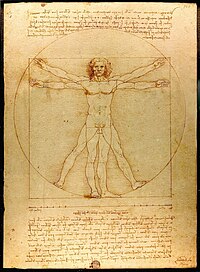

| Part of a series on |

| Humanism |

|---|

|

| Philosophy portal |

Secular Humanism is a secular philosophy that espouses reason, ethics, and the search for human fulfillment, and specifically rejects supernatural and religious dogma as the basis of morality and decision-making. Secular Humanism is a life stance that focuses on the way human beings can lead happy and functional lives.

Secular Humanism is distinguished from various other forms of humanism. Though Secular Humanism posits that human beings are capable of being ethical and moral without religion, or God, that is not to say it assumes humans to be inherently or innately good. Nor does it present humans as "above nature" or superior to it; by contrast, the humanist life stance emphasises the unique responsibility facing humanity and the ethical consequences of human decisions.

The term "Secular Humanism" was coined in the 20th century, and was adopted by non-religious humanists in order to make a clear distinction from "religious humanism". Secular Humanism is also called "scientific humanism". Biologist E. O. Wilson called it "the only worldview compatible with science's growing knowledge of the real world and the laws of nature".[1]

Fundamental to the concept of Secular Humanism is the strongly held belief that ideology—be it religious or political—must be examined by each individual and not simply accepted or rejected on faith.[2] Along with this belief, an essential part of Secular Humanism is a continually adapting search for truth, primarily through science and philosophy.

Tenets

Secular Humanism describes a world view with the following elements and principles:[3]

- Need to test beliefs – A conviction that dogmas, ideologies and traditions, whether religious, political or social, must be weighed and tested by each individual and not simply accepted by faith.

- Reason, evidence, scientific method – A commitment to the use of critical reason, factual evidence and scientific methods of inquiry in seeking solutions to human problems and answers to important human questions.

- Fulfillment, growth, creativity – A primary concern with fulfillment, growth and creativity for both the individual and humankind in general.

- Search for truth – A constant search for objective truth, with the understanding that new knowledge and experience constantly alter our imperfect perception of it.

- This life – A concern for this life (as opposed to an afterlife) and a commitment to making it meaningful through better understanding of ourselves, our history, our intellectual and artistic achievements, and the outlooks of those who differ from us.

- Ethics – A search for viable individual, social and political principles of ethical conduct, judging them on their ability to enhance human well-being and individual responsibility.

- Building a better world – A conviction that with reason, an open exchange of ideas, good will, and tolerance, progress can be made in building a better world for ourselves and our children.

A Secular Humanist Declaration was issued in 1980 by The Council for Democratic and Secular Humanism (CODESH), now the Council for Secular Humanism (CSH). It lays out ten ideals: Free inquiry as opposed to censorship and imposition of belief; separation of church and state; the ideal of freedom from religious control and from jingoistic government control; ethics based on critical intelligence rather than that deduced from religious belief; moral education; religious skepticism; reason; a belief in science and technology as the best way of understanding the world; evolution; and education as the essential method of building humane, free, and democratic societies.[4]

Modern context

While secular humanist organizations are found in all parts of the world, one of the largest humanist organizations in the world (relative to population) is Norway's Human-Etisk Forbund,[5] which had over 70,000 members out of a population of around 4.6 million in 2004.[6]

In certain areas of the world, Secular Humanism finds itself in conflict with religious fundamentalism, especially over the issue of the separation of church and state. Secular humanists may judge religions as superstitious, regressive, and/or closed-minded, while religious fundamentalists see Secular Humanism as a threat to the values set out in their sacred texts.[7]

Comparison with religious humanism

There are a number of ways in which secular and religious humanism can differ:[8]

- Some religious humanists may seek profound "religious" experiences, such as those that others would associate with the presence of God, despite interpreting these experiences differently. Secular humanists would generally not pursue such experiences solely for their own sake.[8]

- Some varieties of nontheistic religious humanism may conceive of the word divine as more than metaphoric even in the absence of a belief in a traditional God; they may believe in ideals that transcend physical reality; or they may conceive of some experiences as numinous or uniquely religious. Secular Humanism regards all such terms as, at best, metaphors for truths rooted in the material world.

- Some varieties of religious humanism, such as Christian humanism include belief in God, traditionally defined. Secular humanists reject the idea of God and the supernatural as irrational and believe that these are not useful concepts for addressing human problems.

Ethics

Secular Humanism does not prescribe a specific theory of morality or code of ethics. As stated by the Council for Secular Humanism,

- It should be noted that Secular Humanism is not so much a specific morality as it is a method for the explanation and discovery of rational moral principles. [9]

Secular Humanism affirms that with the present state of scientific knowledge, dogmatic belief in an absolutist moral/ethical system (e.g. Kantian, Islamic, Christian) is unreasonable. However, it affirms that individuals engaging in rational moral/ethical deliberations can discover some universal "objective standards".

- We are opposed to absolutist morality, yet we maintain that objective standards emerge, and ethical values and principles may be discovered, in the course of ethical deliberation. [9]

Some secular humanists believe that universal moral standards are required for the proper functioning of society. However, they believe such necessary universality can and should be achieved by developing a richer notion of morality through reason, experience and scientific inquiry rather than through faith in a supernatural realm or source.

- Fundamentalists correctly perceive that universal moral standards are required for the proper functioning of society. But they erroneously believe that God is the only possible source of such standards. Philosophers as diverse as Plato, Immanuel Kant, John Stuart Mill, George Edward Moore, and John Rawls have demonstrated that it is possible to have a universal morality without God. Contrary to what the fundamentalists would have us believe, then, what our society really needs is not more religion but a richer notion of the nature of morality. [10]

Humanism in general is known to adopt principles of the Golden Rule, as in the quotation by Oscar Wilde: "Selfishness is not living as one wishes to live, it is asking others to live as one wishes to live." This emphasizes the respect for others' identity and ideals.

History

The term secularism was coined in 1851[11] by George Jacob Holyoake in order to describe "a form of opinion which concerns itself only with questions, the issues of which can be tested by the experience of this life."[12] Once a staunch Owenite, Holyoake was strongly influenced by Auguste Comte, the founder of positivism and of modern sociology. Comte believed human history would progress in a 'law of three stages' from a 'theological' phase, to the 'metaphysical', toward a fully-rational 'positivist' society. In later life, Comte had attempted to introduce a 'religion of humanity' in light of growing anti-religious sentiment and social malaise in revolutionary France. This 'religion' would necessarily fulfil the functional, cohesive role that supernatural religion once served. Whilst Comte's religious movement was unsuccessful, the positivist philosophy of science itself played a major role in the proliferation of secular organizations in the 19th century.

Historical use of the term humanism (reflected in some current academic usage), is related to the writings of pre-Socratic philosophers. These writings were lost to European societies until Renaissance scholars rediscovered them through Muslim sources and translated them from Arabic into European languages.[13] Thus the term humanist can mean a humanities scholar, as well as refer to The Enlightenment/ Renaissance intellectuals, and those who have agreement with the pre-Socratics, as distinct from secular humanists.

In the 1930s, "humanism" was generally used in a religious sense by the Ethical movement in the United States, and not much favoured among the non-religious in Britain. Yet "it was from the Ethical movement that the non-religious philosophical sense of Humanism gradually emerged in Britain, and it was from the convergence of the Ethical and Rationalist movements that this sense of Humanism eventually prevailed throughout the Freethought movement." [14]

See the article on humanism for additional history of this term.

The meaning of the phrase "Secular Humanism" has evolved over time. This phrase was first known to have been used in the 1930s [15], and in 1943, the then Archbishop of Canterbury, William Temple, was reported as warning that the "Christian tradition... was in danger of being undermined by a Secular Humanism which hoped to retain Christian values without Christian faith." [16].

During 1960s and 1970s the term was embraced by some humanists who considered themselves anti-religious [17], as well as those who, although critical of religion in its various guises, preferred a non-religious approach.[3]

The release in 1980 of A Secular Humanist Declaration by the newly formed Council for Democratic and Secular Humanism ("CODESH") gave Secular Humanism an organisational identity.

Negative portrayal by religious right

Starting in the mid-20th century, religious fundamentalists and the religious right began using the term in hostile fashion. Francis A. Schaeffer, (1912–1984), an American theologian based in Switzerland, seizing upon the exclusion of the divine from most humanist writings, argued that rampant secular humanism would lead to moral relativism and ethical bankruptcy in his book How Should We Then Live: The Rise and Decline of Western Thought and Culture (1976). Schaeffer portrayed secular humanism as pernicious and diabolical, and warned it would undermine the moral and spiritual tablet of America. His themes have been very widely repeated in Fundamentalist preaching in North America[18]. Toumey (1993) found that Secular Humanism is typically portrayed as a vast evil conspiracy, deceitful and immoral, responsible for feminism, pornography, abortion, homosexuality, and New Age spirituality[19].

Legal mentions in the United States

The issue of whether and in what sense Secular Humanism might be considered a religion, and what the implications of this would be has become the subject of legal maneuvering and political debate in the United States. The first reference to "Secular Humanism" in a US legal context was in 1961, although church-state separation lawyer Leo Pfeffer had referred to it in his 1958 book, Creeds in Competition.

Case law

Torcaso v. Watkins

The phrase "Secular Humanism" became prominent after it was used in the United States Supreme Court case Torcaso v. Watkins. In the 1961 decision, Justice Hugo Black commented in a footnote, "Among religions in this country which do not teach what would generally be considered a belief in the existence of God are Buddhism, Taoism, Ethical Culture, Secular Humanism, and others."

Fellowship of Humanity v. County of Alameda

The footnote in Torcaso v. Watkins referenced Fellowship of Humanity v. County of Alameda,[20] a 1957 case in which an organization of humanists[21] sought a tax exemption on the ground that they used their property "solely and exclusively for religious worship." Despite the group's non-theistic beliefs, the court determined that the activities of the Fellowship of Humanity, which included weekly Sunday meetings, were analogous to the activities of theistic churches and thus entitled to an exemption.[citation needed]

The Fellowship of Humanity case itself referred to Humanism but did not mention the term Secular Humanism. Nonetheless, this case was cited by Justice Black to justify the inclusion of Secular Humanism in the list of religions in his note. Presumably Justice Black added the word secular to emphasize the non-theistic nature of the Fellowship of Humanity and distinguish their brand of humanism from that associated with, for example, Christian humanism.[citation needed]

Washington Ethical Society v. District of Columbia

Another case alluded to in the Torcaso v. Watkins footnote, and said by some to have established secular humanism as a religion under the law, is the 1957 tax case of Washington Ethical Society v. District of Columbia, 249 F.2d 127 (D.C. Cir. 1957). The Washington Ethical Society functions much like a church, but regards itself as a non-theistic religious institution, honoring the importance of ethical living without mandating a belief in a supernatural origin for ethics. The case involved denial of the Society's application for tax exemption as a religious organization. The U.S. Court of Appeals reversed the Tax Court's ruling, defined the Society as a religious organization, and granted its tax exemption.

The Society terms its practice Ethical Culture. Though Ethical Culture is based on a humanist philosophy, it is regarded by some as a type of religious humanism. Hence, it would seem most accurate to say that this case affirmed that a religion need not be theistic to qualify as a religion under the law, rather than asserting that it established generic secular humanism as a religion.

In the cases of both the Fellowship of Humanity and the Washington Ethical Society, the court decisions turned not so much on the particular beliefs of practitioners as on the function and form of the practice being similar to the function and form of the practices in other religious institutions.

Peloza v. Capistrano School District

The implication in Justice Black's footnote that Secular Humanism is a religion has been seized upon by religious opponents of the teaching of evolution, who have made the argument that teaching evolution amounts to teaching a religious idea.

The claim that Secular Humanism could be considered a religion for legal purposes was examined by the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit in Peloza v. Capistrano School District, 37 F.3d 517 (9th Cir. 1994), cert. denied, 515 U.S. 1173 (1995). In this case, a science teacher argued that, by requiring him to teach evolution, his school district was forcing him to teach the "religion" of Secular Humanism. The Court responded, "We reject this claim because neither the Supreme Court, nor this circuit, has ever held that evolutionism or Secular Humanism are 'religions' for Establishment Clause purposes." The Supreme Court refused to review the case.

The decision in a subsequent case, Kalka v. Hawk et al., offered this commentary:[21]

- The Court's statement in Torcaso does not stand for the proposition that humanism, no matter in what form and no matter how practiced, amounts to a religion under the First Amendment. The Court offered no test for determining what system of beliefs qualified as a "religion" under the First Amendment. The most one may read into the Torcaso footnote is the idea that a particular non-theistic group calling itself the "Fellowship of Humanity" qualified as a religious organization under California law.

Controversy

Some religious groups argue that Secular Humanism—and, by association, secularism—have a religion-like legal status despite the separation of church and state, that secularism in government and in the schools constitutes state favoritism towards a particular religion (namely, the denial of theism), and a double standard is used in granting protections to these groups.

The U.S. courts, however, have consistently rejected this interpretation. Often the discussion is not clearly framed. However, the rationale for believing there is no contradiction appears to include the following:

- Beliefs involved are about more than secularism: Religious status has been granted to various non-theistic humanist organizations. Such organizations typically favor various aspects of secularism. However, humanism embraces a variety of ideas which are not part of secularism, for example, affirming human dignity. Even if a particular brand of humanism were to be regarded as a religion, that would not necessarily make particular positions, such as secularism, religious, as religious status could be based on other considerations.[citation needed]

- Beliefs of a religious group can be non-religious: Even if a group did assert secularism in isolation to be its religion (no instances of this are known), this would not mean that secularism is in general a religious idea. ("Just because people count something in what they say is their religion does not make it inherently religious. If some people start worshipping chairs, chairs shouldn't be kept out of school."[citation needed])

- Court rulings have not been about beliefs: No court rulings on particular non-theistic groups being religious have ever actually ruled that the ideas of these groups were religious per se. Instead, rulings have generally said the groups in question functionally acted like other religious institutions and therefore were entitled to similar protections. (This fact has been obscured by imprecise comments, such as those of Justice Black, but is reflected in the text of particular rulings.)

- Most advocates are not religious: Advocates generally subscribe to scientific ideas, such as the scientific method, as opposed to inherently religious ideas based on religious texts.[citation needed]

Decisions about tax status have been based on whether an organization functions like a church. On the other hand, Establishment Clause cases turn on whether the ideas or symbols involved are inherently religious. An organization can function like a church while advocating beliefs that are not necessarily inherently religious.

Author Marci Hamilton has pointed out: "Moreover, the debate is not between secularists and the religious. The debate is believers and non-believers on the one side debating believers and non-believers on the other side. You've got citizens who are...of faith who believe in the separation of church and state and you have a set of believers who do not believe in the separation of church and state."[22]

In a mockery of an Alabama judge's reference to Secular Humanism as a religion, the musician Frank Zappa, who was also a free speech advocate, established the "Church of American Secular Humanism."[23] The fact that the initials of the organization formed the acronym "CASH" was part of the joke. In 1981, the humorous columnist Art Buchwald wrote a piece entitled, "Secular Humanists: Threat or Menace?" In it, he poked fun at alarm about Secular Humanism.[24]

Legislation

Hatch amendment

The Education for Economic Security Act of 1984 included a section, Section 20 U.S.C.A. 4059, which initially read: "Grants under this subchapter ['Magnet School Assistance] may not be used for consultants, for transportation or for any activity which does not augment academic improvement." With no public notice, Senator Orrin Hatch tacked on to the proposed exclusionary subsection the words "or for any course of instruction the substance of which is Secular Humanism." Implementation of this provision ran into practical problems because neither the Senator's staff, nor the Senate's Committee on Labor and Human Resources, nor the Department of Justice could propose a definition of what would constitute a "course of instruction the substance of which is secular Humanism." So, this determination was left up to local school boards.

The provision provoked a storm of controversy which within a year led Senator Hatch to propose, and Congress to pass, an amendment to delete from the statute all reference to Secular Humanism.

While this episode did not dissuade fundamentalists from continuing to object to what they regarded as the "teaching of Secular Humanism," it did point out the vagueness of the claim.

Notable people

Some notable secular humanists:

- Steve Allen

- Isaac Asimov

- Jeremy Bentham

- Steve Benson Pulitzer Prize-winning liberal editorial cartoonist for The Arizona Republic.

- Albert Camus

- Noam Chomsky

- Sir Arthur C. Clarke

- Aaron Copland [25]

- Brian Cox [1]

- Richard Dawkins

- Daniel Dennett

- Roger Ebert

- Umberto Eco

- Sanal Edamaruku

- Albert Einstein

- Karl Marx

- Friedrich Engels

- Scott Fellows

- Tom Flynn, Senior Editor of Free Inquiry magazine.[26].

- E. M. Forster (see in particular his "What I Believe")

- Daniel Handler

- Sam Harris

- Hubert Harrison

- Andreas Heldal-Lund

- Nat Hentoff

- Christopher Hitchens

- Julian Huxley – first President of the IHEU, a major Humanist organisation

- Penn Jillette

- Paul Kurtz – founding President of the Council for Secular Humanism

- Corliss Lamont

- John Lennon

- Bill Maher

- Terence McKenna

- Taslima Nasrin

- Kathleen Nott

- Gary Numan

- Linus Pauling

- Steven Pinker

- Terry Pratchett

- Philip Pullman

- James Randi

- Winwood Reade

- Gene Roddenberry – inspired Star Trek theme of self-styled gods exposed as impostors

- Salman Rushdie

- Bertrand Russell

- Carl Sagan

- Charles M. Schulz

- Michael Shermer

- Peter Singer

- Linda Smith

- Jon Stewart

- Rodrigue Tremblay

- Neil DeGrasse Tyson

- Björn Ulvaeus

- Kurt Vonnegut

- Ibn Warraq

- James D. Watson

- Joss Whedon

- E. O. Wilson

- Thom Yorke

- Frank Zappa

Manifestos

There are numerous Humanist Manifestos and Declarations, including the following:

- Humanist Manifesto I (1933)

- Humanist Manifesto II (1973)

- A Secular Humanist Declaration (1980)

- A Declaration of Interdependence (1988)

- IHEU Minimum Statement on Humanism (1996)

- HUMANISM: Why, What, and What For, In 882 Words (1996)

- Humanist Manifesto 2000: A Call For A New Planetary Humanism (2000)

- The Affirmations of Humanism: A Statement of Principles

- Amsterdam Declaration (2002)

- Humanism and Its Aspirations

- Humanist Manifesto III (Humanism And Its Aspirations) (2003)

See also

Related Organisations

- American Atheists

- American Humanist Association

- Brights

- British Humanist Association

- Camp Quest

- Center for Inquiry

- City Congregation for Humanistic Judaism

- Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal

- Council for Secular Humanism (formerly CODESH)

- Freedom From Religion Foundation

- Godless Americans PAC (political action committee)

- Humani (the Humanist Association of Northern Ireland)

- Humanist Association of Canada

- Humanist Association of Ireland

- Humanist Society of Scotland

- Institute for Humanist Studies

- International Humanist and Ethical Union

- Internet Infidels

- Military Association of Atheists and Freethinkers

- National Center for Science Education

- New Zealand Association of Rationalists and Humanists

- Quackwatch

- Scouting for All

- Skeptics Society

- Secular Student Alliance

- Secular Web

- Society for Humanistic Judaism

Related philosophies

- Empiricism

- Epicureanism

- Eupraxsophy

- Extropianism

- Freethought

- Humanism

- Morality without religion

- Objectivism

- Philosophical naturalism

- Rationalism

- Religious humanism

- Secularism

- Transhumanism

- Naturalistic pantheism

Further reading

- Bullock Alan. The Humanist Tradition in the West (1985), by a leading historian.

- Friess Horace L. Felix Adler and Ethical Culture (1981).

- Pfeffer, Leo. "The 'Religion' of Secular Humanism," Journal of Church and State, Summer 1987, Vol. 29 Issue 3, pp 495–507

- Radest, Howard B. The Devil and Secular Humanism: The Children of the Enlightenment (1990) online edition a favorable account

- Toumey, Christopher P. "Evolution and secular humanism," Journal of the American Academy of Religion, Summer 1993, Vol. 61 Issue 2, pp 275–301, focused on fundamentalist attacks

Primary sources

- Adler Felix. An Ethical Philosophy of Life (1918).

- Ericson Edward L. The Humanist Way 1988.

- Frankel Charles. The Case for Modern Man (1956).

- Hook Sidney. Out of Step: An Unquiet Life in the 20th Century (1987).

- Huxley Julian. Essay of a Humanist (1964).

- Russell Bertrand. Why I Am Not a Christian (1957).

Footnotes

- ^ (Harvard Magazine December 2005, p. 33.)

- ^ Free Speech on Evolution Campaign Main Page Discovery Institute, Center for Science and Culture.

- ^ a b "What Is Secular Humanism?". Council for Secular Humanism.

- ^ the Council for Secular Humanism (1980). "A Secular Humanist Declaration". the Council for Secular Humanism. Retrieved 2008-11-27.

- ^ Human-Etisk Forbund

- ^ Members of religious and philosophical communities outside the Church of Norway. 1990–2004

- ^ IslamWay Radio

- ^ a b Council for Secular Humanism – "Religious and Secular Humanism: What's the difference?"

- ^ a b A Secular Humanist Declaration

- ^ http://www.secularhumanism.org/index.php?section=library&page=schick_17_3 Morality Requires God ... or Does It? by Theodore Schick, Jr.

- ^ Holyoake, G.J. (1896). The Origin and Nature of Secularism. London: Watts & Co., p.50.

- ^ Secularism 101: Defining Secularism: Origins with George Jacob Holyoake

- ^ Islamic political philosophy: Al-Farabi, Avicenna, Averroes

- ^ Walter, Nicolas (1997). Humanism: what's in the word? London: RPA/BHA/Secular Society Ltd, p.43.

- ^ See "Unemployed at service: church and the world", The Guardian, 25 May 1935, p.18: citing the comments of Rev. W.G. Peck, rector of St. John the Baptist, Hulme Manchester, concerning "The modern age of secular humanism". Guardian and Observer Digital Archive

- ^ "Free Church ministers in Anglican pulpits. Dr Temple's call: the South India Scheme." The Guardian, 26 May 1943, p.6 Guardian and Observer Digital Archive

- ^ See Mouat, Kit (1972) An Introduction to Secular Humanism. Haywards Heath: Charles Clarke Ltd. Also, The Freethinker began to use the phrase "secular humanist monthly" on its front page masthead.

- ^ Randall Balmer, Encyclopedia of Evangelicalism 2002 p. 516

- ^ Christopher P. Toumey, "Evolution and secular humanism," Journal of the American Academy of Religion, Summer 1993, Vol. 61 Issue 2, pp 275–301

- ^ Fellowship of Humanity v. County of Alameda, 153 Cal.App.2d 673, 315 P.2d 394 (1957).

- ^ a b Ben Kalka v Kathleen Hawk, et al. (US D.C. Appeals No. 98-5485, 2000)

- ^ Point of Inquiry podcast (17:44), February 3, 2006.

- ^ Church of American Secular Humanism – Zappa Wiki Jawaka

- ^ Secular Humanists: threat or menace, reprinted in Williamette Freethinker, May 1998

- ^ To all appearances, and by all accounts, he was what many might call a secular humanist." Professor Leon Botstein writes: "He emerged as an adult without an ongoing connection to religion."

- ^ Flynn, Tom (June–July 2008). "Secularization Renewed?". Free Inquiry. 29 (4): 14–15.

External links

Related to topic 'religion'

- Secular Humanism in U. S. Supreme Court Cases

- Ben Kalka v Kathleen Hawk, et al. (US D.C. Appeals No. 98-5485, 2000)

- Is Secular Humanism a Religion? by Austin Clyne, a Regional Director for the Council for Secular Humanism