Longevity: Difference between revisions

| Line 115: | Line 115: | ||

*[[Hayflick limit]] |

*[[Hayflick limit]] |

||

*[[Indefinite lifespan]] |

*[[Indefinite lifespan]] |

||

*[[Immortalist Institute |

*[[imminst.org]] The Immortalist Institute |

||

*[[Life extension]] |

*[[Life extension]] |

||

*[[List of last survivors of historical events]] |

*[[List of last survivors of historical events]] |

||

Revision as of 21:39, 25 January 2012

The word "longevity" is sometimes used as a synonym for "life expectancy" in demography or known as "long life", especially when it concerns someone or something lasting longer than expected (an ancient tree, for example).

Reflections on longevity have usually gone beyond acknowledging the brevity of human life and have included thinking about methods to extend life. Longevity has been a topic not only for the scientific community but also for writers of travel, science fiction, and utopian novels.

There are many difficulties in authenticating the longest human life span ever by modern verification standards, owing to inaccurate or incomplete birth statistics. Fiction, legend, and folklore have proposed or claimed life spans in the past or future vastly longer than those verified by modern standards, and longevity narratives and unverified longevity claims frequently speak of their existence in the present.

A life annuity is a form of longevity insurance.

History

A remarkable statement mentioned by Diogenes Laertius (c. 250 AD) is the earliest (or at least one of the earliest) references about plausible centenarian longevity given by a scientist, the astronomer Hipparchus of Nicea (c. 185 – c. 120 BC), who, according to the doxographer, was assured that the philosopher Democritus of Abdera (c. 470/460 – c. 370/360 BC) lived 109 years. All other accounts given by the ancients about the age of Democritus appear, without giving any specific age, to agree that the philosopher lived over 100 years. This possibility is likely, given that many ancient Greek philosophers are thought to have lived over the age of 90 (e.g., Xenophanes of Colophon, c. 570/565 – c. 475/470 BC, Pyrrho of Ellis, c. 360 – c. 270 BC, Eratosthenes of Cirene, c. 285 – c. 190 BC, etc.). The case of Democritus is different from the case of, for example, Epimenides of Crete (7th, 6th centuries BC), who is said to have lived 154, 157 or 290 years, as has been said about countless elders even during the last centuries as well as in the present time. These cases are not verifiable by modern means.

Present life expectancy

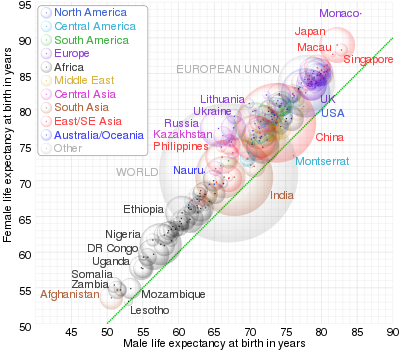

Various factors contribute to an individual's longevity. Significant factors in life expectancy include gender, genetics, access to health care, hygiene, diet and nutrition, exercise, lifestyle, and crime rates. Below is a list of life expectancies in different types of countries:[3]

- Developed countries: 77–83 years (e.g. Canada: 81.29 years, 2010 est.)

- Developing countries: 32–80 years (e.g. Mozambique: 41.37 years, 2010 est.)

Population longevities are increasing as life expectancies around the world grow:[3][4]

- Spain: 79.08 years in 2002, 81.07 years in 2010

- Australia: 80 years in 2002, 81.72 years in 2010

- Italy: 79.25 years in 2002, 80.33 years in 2010

- France: 79.05 years in 2002, 81.09 years in 2010

- Germany: 77.78 years in 2002, 79.41 years in 2010

- UK: 77.99 years in 2002, 79.92 years in 2010

- USA: 77.4 years in 2002, 78.24 years in 2010

Long-lived individuals

The Gerontology Research Group validates current longevity records by modern standards, and maintains a list of supercentenarians; many other unvalidated longevity claims exist. Record-holding individuals include:

- Jeanne Calment (1875–1997, 122 years, 164 days): the oldest person in history whose age has been verified by modern documentation. This defines the modern human life span, which is set by the oldest documented individual who ever lived.

- Sarah Knauss (1880–1999, 119 years, 97 days): The second oldest documented person in modern times and the oldest American.

- Christian Mortensen (1882–1998, 115 years, 252 days): the oldest man in history whose age has been verified by modern documentation.

- Besse Cooper (1896–): Celebrated her 115th birthday in August 2011, currently the oldest living person.

Longevity and lifestyle

Evidence-based studies indicate that longevity is based on two major factors, genetics and lifestyle choices.[5] Twin studies have estimated that approximately 20-30% of an individual’s lifespan is related to genetics, the rest is due to individual behaviors and environmental factors which can be modified.[6] In addition, it found that lifestyle plays almost no factor in health and longevity after the age of 80, and that almost everything in advanced age is due to genetic factors.

In preindustrial times, deaths at young and middle age were common, and lifespans over 70 years were comparatively rare. This is not due to genetics, but because of environmental factors such as disease, accidents, and malnutrition, especially since the former were not generally treatable with pre-20th century medicine. Deaths from childbirth were common in women, and many children did not live past infancy. In addition, most people who did attain old age were likely to die quickly from the above-mentioned untreatable health problems. Despite this, we do find a large number of examples of pre-20th century individuals attaining lifespans of 75 years or greater, including Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, Cato the Elder, Thomas Hobbes, Eric of Pomerania, Christopher Polhem, and Michaelangelo. This was also true for poorer people like peasants or laborers. Genealogists will almost certainly find ancestors living to their 70s, 80s and even 90s several hundred years ago.

For example, an 1871 census in the UK (the first of its kind) found the average male life expectancy as being 44, but if infant mortality is subtracted, males who lived to adulthood averaged 75 years. The present male life expectancy in the UK is 77 years for males and 81 for females (the United States averages 74 for males and 80 for females).

Studies have shown that African-American males have the shortest lifespans of any group of people in the US, averaging only 69 years (white females average the longest). This reflects overall poorer health and greater prevalence of heart disease, obesity, diabetes, and cancer among African-American men.

Women normally outlive men, and this was as true in pre-industrial times as today. Theories for this include smaller bodies (and thus less stress on the heart), a stronger immune system (since testosterone acts as an immunosuppressant), and less tendency to engage in physically dangerous activities. It is also theorized that women have an evolutionary reason to live longer so as to help care for grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

Study of the regions of the world known as blue zones,[7] where people commonly live active lives past 100 years of age, have speculated that longevity is related to a healthy social and family life, not smoking, eating a plant-based diet, frequent consumption of legumes and nuts, and engaging in regular physical activity. In another well-designed cohort study, the combination of a plant based diet, frequent consumption of nuts, regular physical activity, normal BMI, and not smoking accounted for differences up to 10 years in life expectancy.[8] The Alameda County Study hypothesized three additional lifestyle characteristics that promote longevity: limiting alcohol consumption, sleeping 7 to 8 hours per night, and not snacking (eating between meals).[9]

Longevity traditions

Longevity traditions are traditions about long-lived people (generally supercentenarians), and practices that have been believed to confer longevity.[10][11] A comparison and contrast of "longevity in antiquity" (such as the Sumerian King List, the genealogies of Genesis, and the Persian Shahnameh) with "longevity in historical times" (common-era cases through twentieth-century news reports) is elaborated in detail in Lucian Boia's 2004 book Forever Young: A Cultural History of Longevity from Antiquity to the Present and other sources.[12]

The Fountain of Youth reputedly restores the youth of anyone who drinks of its waters. The New Testament, following older Jewish tradition, attributes healing to the Pool of Bethesda when the waters are "stirred" by an angel.[13] After the death of Juan Ponce de León, Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo wrote in Historia General y Natural de las Indias (1535) that Ponce de León was looking for the waters of Bimini to cure his aging.[14] Traditions that have been believed to confer greater human longevity also include alchemy,[15] such as that attributed to Nicolas Flamel. In the modern era, the Okinawa diet has some reputation of linkage to exceptionally high ages.[16]

More recent longevity claims are subcategorized by many editions of Guinness World Records into four groups: "In late life, very old people often tend to advance their ages at the rate of about 17 years per decade .... Several celebrated super-centenarians (over 110 years) are believed to have been double lives (father and son, relations with the same names or successive bearers of a title) .... A number of instances have been commercially sponsored, while a fourth category of recent claims are those made for political ends ...."[17] The estimate of 17 years per decade was corroborated by the 1901 and 1911 British censuses.[17] Mazess and Forman also discovered in 1978 that inhabitants of Vilcabamba, Ecuador, claimed excessive longevity by using their fathers' and grandfathers' baptismal entries.[17][18] Time magazine considered that, by the Soviet Union, longevity had been elevated to a state-supported "Methuselah cult".[19] Robert L. Ripley regularly reported supercentenarian claims in Ripley's Believe It or Not!, usually citing his own reputation as a fact-checker to claim reliability.[20]

Future

The U.S. Census Bureau view on the future of longevity is that life expectancy in the United States will be in the mid-80s by 2050 (up from 77.85 in 2006) and will top out eventually in the low 90s, barring major scientific advances that can change the rate of human aging itself, as opposed to merely treating the effects of aging as is done today. The Census Bureau also predicted that the United States would have 5.3 million people aged over 100 in 2100. The United Nations has also made projections far out into the future, up to 2300, at which point it projects that life expectancies in most developed countries will be between 100 and 106 years and still rising, though more and more slowly than before. These projections also suggest that life expectancies in poor countries will still be less than those in rich countries in 2300, in some cases by as much as 20 years. The UN itself mentioned that gaps in life expectancy so far in the future may well not exist, especially since the exchange of technology between rich and poor countries and the industrialization and development of poor countries may cause their life expectancies to converge fully with those of rich countries long before that point, similarly to the way life expectancies between rich and poor countries have already been converging over the last 60 years as better medicine, technology, and living conditions became accessible to many people in poor countries. The UN has warned that these projections are uncertain, and cautions that any change or advancement in medical technology could invalidate such projections.[21]

Recent increases in the rates of lifestyle diseases, such as obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and heart disease, may drastically slow or reverse this trend toward increasing life expectancy in the developed world.

Scientist Olshansky examined how much mortality from various causes would have to drop in order to boost life expectancy and concluded that most of the past increases in life expectancy occurred because of improved survival rates for young people. He states that it seems unlikely that life expectancy at birth will ever exceed 85 years.[22]

However, since 1840, record life expectancy has risen linearly for men and women, albeit more slowly for men. For women the increase has been almost three months per year. In light of steady increase, without any sign of limitation, the suggestion that life expectancy will top out must be treated with caution. Scientists Oeppen and Vaupel observe that experts who assert that "life expectancy is approaching a ceiling ... have repeatedly been proven wrong." It is thought that life expectancy for women has increased more dramatically owing to the considerable advances in medicine related to childbirth.[23]

Mice have been genetically engineered to live twice as long as ordinary mice. Drugs such as deprenyl are a part of the prescribing pharmacopia of veterinarians specifically to increase mammal lifespan. A large plurality of research chemicals have been described at the scientific literature that increase the lifespan of a number of species.

Some argue that molecular nanotechnology will greatly extend human life spans. If the rate of increase of life span can be raised with these technologies to a level of twelve months increase per year, this is defined as effective biological immortality and is the goal of radical life extension.

Non-human biological longevity

Currently living:

- Methuselah: 4,800-year-old bristlecone pine in the White Mountains of California, the oldest currently living organism known.

Non-living:

- Possibly 250 million year-old bacteria, bacillus permians, were revived from stasis after being found in sodium chloride crystals in a cavern in New Mexico. Russell Vreeland, and colleagues from West Chester University in Pennsylvania, reported on October 18, 2000 that they had revived the halobacteria after bathing them with a nutrient solution. Having supposedly survived for 250 million years, they would be the oldest living organisms ever recorded.[24] However, their findings have not been universally accepted.[25]

- A bristlecone pine nicknamed "Prometheus", felled in the Great Basin National Park in Nevada in 1964, found to be about 4,900 years old, is the longest-lived single organism known.[26]

- A quahog clam (Arctica islandica), dredged from off the coast of Iceland in 2007, was found to be from 400 to 410 years old, the oldest animal documented. Other clams of the species have been recorded as living up to 374 years.[27]

- Lamellibrachia luymesi, a deep-sea cold-seep tubeworm, is estimated to reach ages of over 250 years based on a model of its growth rates.[citation needed]

- Hanako (Koi Fish) was the longest-lived vertebrate ever recorded at 226 years.

- A Bowhead Whale killed in a hunt was found to be approximately 211 years old (possibly up to 245 years old), the longest lived mammal known.[28]

- Tu'i Malila, a radiated tortoise presented to the Tongan royal family by Captain Cook, lived for over 185 years. It is the oldest documented reptile. Adwaitya, an Aldabra Giant Tortoise, may have lived for up to 250 years.

Biological immortality

Certain exotic organisms do not seem to be subject to aging and can live indefinitely. Examples include Tardigrades and Hydras. That is not to say that these organisms cannot die, merely that they only die as a result of disease or injury rather than age-related deterioration (and that they are not subject to the Hayflick limit).

See also

- Actuarial Science

- Alameda County Study

- Alliance for Aging Research

- Biodemography

- Biodemography of human longevity

- Calorie restriction

- List of centenarians

- DNA damage theory of aging

- Gerontology Research Group

- Hayflick limit

- Indefinite lifespan

- imminst.org The Immortalist Institute

- Life extension

- List of last survivors of historical events

- Lloyd Demetrius

- Maximum life span

- Methuselah Foundation

- Mitohormesis

- Oldest viable seed

- Reliability theory of aging and longevity

- Research into centenarians

- Resveratrol

- Senescence

- Strategies for Engineered Negligible Senescence

Notes

- ^ [1]

- ^ [2]

- ^ a b The US Central Intelligence Agency, 2010, CIA World Factbook, retrieved 12 Jan. 2011, https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/index.html

- ^ The US Central Intelligence Agency, 2002, CIA World Factbook, retrieved 12 Jan. 2011, http://www.theodora.com/wfb/2002/index.html

- ^ Marziali, Carl (7 December 2010). "Reaching Toward the Fountain of Youth". USC Trojan Family Magazine. Retrieved 7 December 2010.

- ^ Hjelmborg, J.; Skytthe, Axel; Vaupel, James W.; McGue, Matt; Koskenvuo, Markku; Kaprio, Jaakko; Pedersen, Nancy L.; Christensen, Kaare; et al. (2006). "Genetic influence on human lifespan and longevity". Human Genetics. 119 (3): 312–321. doi:10.1007/s00439-006-0144-y.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|last2=(help) - ^ Buettner, D. (2008). The Blue Zones. Washington, DC: National Geographic Society.

- ^ Fraser, Gary E.; Shavlik, David J. (2001). "Ten Years of Life: Is It a Matter of Choice?". Archives of Internal Medicine. 161 (13): 1645–1652. doi:10.1001/archinte.161.13.1645. PMID 11434797.

- ^ Kaplan, George A.; Seeman, Teresa E.; Cohen, Richard D.; Guralnik, J; et al. (1987). "Mortality Among the Elderly in the Alameda County Study: Behavioral and Demographic Risk Factors". American Journal of Public Health. 77 (3): 307–312. doi:10.2105/AJPH.77.3.307.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|last4=(help) - ^ Ni, Maoshing (2006). Secrets of Longevity. Chronicle Books. ISBN 9780811849494.

Chuan xiong ... has long been a key herb in the longevity tradition of China, prized for its powers to boost the immune system, activate blood circulation, and relieve pain.

- ^ Fulder, Stephen (1983). An End to Ageing: Remedies for Life. Destiny Books. ISBN 9780892810444.

Taoist devotion to immortality is important to us for two reasons. The techniques may be of considerable value to our goal of a healthy old age, if we can understand and adapt them. Secondly, the Taoist longevity tradition has brought us many interesting remedies.

- ^ Vallin, Jacques; Meslé, France (February 2001). "Living Beyond the Age of 100" (PDF). Bulletin Mensuel d'Information de l'Institut National d'Etudes Demographiques: Population & Sociétés (365). Institut National d'Etudes Demographiques.

- ^ John 5:4.

- ^ Fernández de Oviedo, Gonzalo. Historia General y Natural de las Indias, book 16, chapter XI.

- ^ Kohn, Livia (2001). Daoism and Chinese Culture. Three Pines Press. pp. 4, 84. ISBN 9781931483001.

- ^ Willcox, Willcox, and Suzuki. The Okinawa program: Learn the secrets to healthy longevity. p. 3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Guinness Book of World Records. 1983. pp. 16–19.

- ^ Leaf, Alexander (January 1973). "Search for the Oldest People". National Geographic. pp. 93–118.

- ^ "No Methuselahs". Time Magazine. 1974-08-12. Retrieved 2009-05-13.

- ^ Ripley Enterprises, Inc. (September 1969). Ripley's Believe It or Not! 15th Series. New York City: Pocket Books. pp. 112, 84, 56.

The Old Man of the Sea / Yaupa / a native of Futuna, one of the New Hebrides Islands / regularly worked his own farm at the age of 130 / He died in 1899 of measles — a children's disease ... Horoz Ali, the last Turkish gatekeeper of Nicosia, Cyprus, lived to the age of 120 ... Francisco Huppazoli (1587–1702) of Casale, Italy, lived 114 years without a day's illness and had 4 children by his 5th wife — whom he married at the age of 98

- ^ World Population to 2300, United Nations

- ^ Jennifer Couzin-Frankel (29 July 2011). "A Pitched Battle Over Life Span". Science. 333 (6042): 549–50. doi:10.1126/science.333.6042.549. PMID 21798928.

- ^ Oeppen, Jim (2002-05-10). "Broken Limits to Life Expectancy". Science. 296 (5570). Washington, D.C.: American Association for the Advancement of Science: 1029–1031. doi:10.1126/science.1069675. PMID 12004104. Retrieved 2009-05-17.

{{cite journal}}: Check|authorlink=value (help); External link in|authorlink=|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ 250-Million-Year-Old Bacillus permians Halobacteria Revived. October 22, 2000. Bioinformatics Organization. J.W. Bizzaro. [3]

- ^ "The Permian Bacterium that Isn't". Oxford Journals. 2001-02-15. Retrieved 2010-11-16.

- ^ Hall, Carl. "Staying Alive". San Francisco Chronicle, 23 August 1998.

- ^ Bangor University: 400 year old Clam Found(retrieved 29 October 2007) BBC News: Ming the clam is 'oldest animal' (retrieved 29 October 2007)

- ^ Rozell (2001) "Bowhead Whales May Be the World's Oldest Mammals", Alaska Science Forum, Article 1529 (retrieved 29 October 2007)

References

- Leonid A. Gavrilov & Natalia S. Gavrilova (1991), The Biology of Life Span: A Quantitative Approach. New York: Harwood Academic Publisher, ISBN

- John Robbins' Healthy at 100 garners evidence from many scientific sources to account for the extraordinary longevity of Abkhasians in the Caucasus, Vilcabambans in the Andes, Hunzas in Central Asia, and Okinawans.

- Gavrilova N.S., Gavrilov L.A. Search for Mechanisms of Exceptional Human Longevity. Rejuvenation Research, 2010, 13(2-3): 262-264.

- Beyond The 120-Year Diet, by Roy L. Walford, M.D.

- Gavrilova N.S., Gavrilov L.A. Can exceptional longevity be predicted? Contingencies [Journal of the American Academy of Actuaries], 2008, July/August issue, pp. 82-88.

- Forever Young: A Cultural History of Longevity from Antiquity to the Present Door Lucian Boia,2004 ISBN 1861891547

- Gavrilova N.S., Gavrilov L.A. Search for Predictors of Exceptional Human Longevity: Using Computerized Genealogies and Internet Resources for Human Longevity Studies. North American Actuarial Journal, 2007, 11(1): 49-67

- James R. Carey & Debra S. Judge: Longevity records: Life Spans of Mammals, Birds, Amphibians, reptiles, and Fish. Odense Monographs on Population Aging 8, 2000. ISBN 87-7838-539-3

- Gavrilov LA, Gavrilova NS. Reliability Theory of Aging and Longevity. In: Masoro E.J. & Austad S.N.. (eds.): Handbook of the Biology of Aging, Sixth Edition. Academic Press. San Diego, CA, USA, 2006, 3-42.

- James R. Carey: Longevity. The biology and Demography of Life Span. Princeton University Press 2003 ISBN 0-691-08848-9

- Gavrilova, N.S., Gavrilov, L.A. Human longevity and reproduction: An evolutionary perspective. In: Voland, E., Chasiotis, A. & Schiefenhoevel, W. (eds.): Grandmotherhood - The Evolutionary Significance of the Second Half of Female Life. Rutgers University Press. New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 2005, 59-80.

External links

This article's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. (August 2010) |

- The British Longevity Society

- American Federation for Aging Research

- Alliance for Aging Research

- Longevity and Pensions, Allianz Knowledge Site, February 2008

- The Longevity Project

- International Longevity Center

- International Longevity Centre - UK

- The Okinawa Centenarian Study

- Longevity and Aging of Animals

- Longevity Science

- Mechanisms of Aging

- International Research Centre for Healthy Ageing & Longevity (IRCHAL)

- HOW TO LIVE FOREVER | Documentary featuring interviews with the world's oldest people.