Kingdom of Bavaria: Difference between revisions

| Line 139: | Line 139: | ||

In 1914, a clash of alliances occurred over [[Austria-Hungary]]'s invasion of [[Serbia]] following the assassination of Austrian [[Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria|Archduke Franz Ferdinand]] by a [[Bosnian Serb]] militant. Germany went to the side of its former rival-turned-ally, Austria-Hungary, while France, Russia, and the United Kingdom declared war on Austria-Hungary and Germany. Initially, in Bavaria and all across Germany, recruits flocked enthusiastically to the German Army. At the outbreak of World War I King Ludwig III sent an official dispatch to Berlin to express Bavaria's solidarity. Later Ludwig even claimed annexations for Bavaria (Alsace and the city of Antwerp in Belgium, to receive an access to the sea). His hidden agenda was to maintain the balance of power between Prussia and Bavaria within the German Empire after a victory. Over time, with a stalemated and bloody war on the western front, Bavarians, like many Germans, grew weary of a continuing war. |

In 1914, a clash of alliances occurred over [[Austria-Hungary]]'s invasion of [[Serbia]] following the assassination of Austrian [[Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria|Archduke Franz Ferdinand]] by a [[Bosnian Serb]] militant. Germany went to the side of its former rival-turned-ally, Austria-Hungary, while France, Russia, and the United Kingdom declared war on Austria-Hungary and Germany. Initially, in Bavaria and all across Germany, recruits flocked enthusiastically to the German Army. At the outbreak of World War I King Ludwig III sent an official dispatch to Berlin to express Bavaria's solidarity. Later Ludwig even claimed annexations for Bavaria (Alsace and the city of Antwerp in Belgium, to receive an access to the sea). His hidden agenda was to maintain the balance of power between Prussia and Bavaria within the German Empire after a victory. Over time, with a stalemated and bloody war on the western front, Bavarians, like many Germans, grew weary of a continuing war. |

||

In 1917, when Germany's situation had gradually worsened due to [[World War I]], the Bavarian Prime Minister [[Georg von Hertling]] became German Chancellor and Prime Minister of Prussia and [[Otto Ritter von Dandl]] was made new Prime Minister of Bavaria. Accused of showing blind loyalty to Prussia, Ludwig III became increasingly unpopular during the war. In 1918, the kingdom attempted to negotiate a separate peace with the allies but failed. By 1918, civil unrest was spreading across Bavaria and Germany; Bavarian defiance to Prussian hegemony and Bavarian separatism being key motivators. In November 1918, [[William II, German Emperor|William II]] abdicated the throne of Germany, and Ludwig III, along with the other German monarchs, issuing the [[Anif declaration]], followed in abdication shortly afterwards. With this, the [[House of Wittelsbach|Wittelsbach]] dynasty came to an end, and the former Kingdom of Bavaria became the [[Free State of Bavaria]], which it is still named today. |

In 1917, when Germany's situation had gradually worsened due to [[World War I]], the Bavarian Prime Minister [[Georg von Hertling]] became German Chancellor and Prime Minister of Prussia and [[Otto Ritter von Dandl]] was made new Prime Minister of Bavaria. Accused of showing blind loyalty to Prussia, Ludwig III became increasingly unpopular during the war. In 1918, the kingdom attempted to negotiate a separate peace with the allies but failed. By 1918, civil unrest was spreading across Bavaria and Germany; Bavarian defiance to Prussian hegemony and Bavarian separatism being key motivators. In November 1918, [[William II, German Emperor|William II]] abdicated the throne of Germany, and Ludwig III, along with the other German monarchs, issuing the [[Anif declaration]], followed in abdication shortly afterwards. With this, the [[House of Wittelsbach|Wittelsbach]] dynasty came to an end, and the former Kingdom of Bavaria became the [[Free State of Bavaria]], which it is still named today. The funeral of Lugwig III in 1921 was feared or hoped to spark a [[Monarchism in Bavaria after 1918|restoration of the monarchy]]. Despite the abolition of the monarchy, the former King was laid to rest in front of the royal family, the Bavarian government, military personnel, and an estimated 100,000 spectators, in the style of royal funerals. Prince Rupprecht did not wish to use the occasion of the passing of his father to reestablish the monarchy by force, preferring to do so by legal means. [[Michael von Faulhaber]], [[Archbishop of Munich]], in his funeral speech, made a clear commitment to the monarchy while Rupprecht only declared that he had stepped into his birthright.<ref>[http://www.historisches-lexikon-bayerns.de/artikel/artikel_44449 Beisetzung Ludwigs III., München, 5. November 1921] {{de icon}} Historisches Lexikon Bayerns – Funeral of Ludwig III, accessed: 1 July 2011</ref> |

||

==Geography, administrative regions and population== |

==Geography, administrative regions and population== |

||

Revision as of 16:23, 28 April 2012

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2009) |

Kingdom of Bavaria Königreich Bayern | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1806–1918 | |||||||||||||

| Anthem: Königsstrophe "Kings stanze" | |||||||||||||

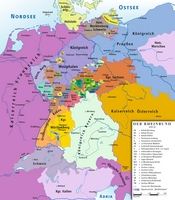

The Kingdom of Bavaria within the German Empire. | |||||||||||||

| Status | State of the Confederation of the Rhine (1806–1813) State of the German Confederation (1815–1866) Federated state of the German Empire (1871–1918) | ||||||||||||

| Capital | Munich | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | Austro-Bavarian, Swabian-German | ||||||||||||

| Religion | Evangelical, Roman Catholic | ||||||||||||

| Government | Constitutional Monarchy | ||||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||||

• 1806–1825 | Maximilian I Joseph | ||||||||||||

• 1825–1848 | Ludwig I | ||||||||||||

• 1848–1864 | Maximilian II | ||||||||||||

• 1864–1886 | Ludwig II | ||||||||||||

• 1886–1913 | Otto | ||||||||||||

• 1913–1918 | Ludwig III | ||||||||||||

| Prince Regent | |||||||||||||

• 1886–1912 | Luitpold Karl | ||||||||||||

• 1912–1913 | Ludwig Luitpold | ||||||||||||

| Minister-President | |||||||||||||

• 1806–1817 | Maximilian von Montgelas | ||||||||||||

• 1917–1918 | Otto Ritter von Dandl | ||||||||||||

| Legislature | Landtag | ||||||||||||

• Upper Chamber | Herrenhaus | ||||||||||||

• Lower Chamber | Abgeordnetenhaus | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | Napoleonic Wars / WWI | ||||||||||||

| 26 December 1805 | |||||||||||||

• Established | 01 January 1806 | ||||||||||||

| 08 October 1813 | |||||||||||||

| 30 May 1814 | |||||||||||||

| 18 January 1871 | |||||||||||||

| 09 November 1918 | |||||||||||||

| 12 November 1918 | |||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||

| 1910 | 75,865 km2 (29,292 sq mi) | ||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||

• 1910 | 6,524,372 | ||||||||||||

| Currency | Bavarian Gulden, (1806–1873) German Goldmark, (1873–1914) German Papiermark (1914–1918) | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

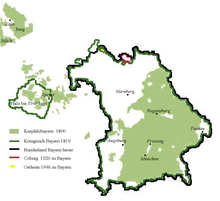

The Kingdom of Bavaria (German: Königreich Bayern) was a German state that existed from 1806 to 1918. The Bavarian Elector Maximilian IV Joseph of the House of Wittelsbach became the first King of Bavaria in 1806 as Maximilian I Joseph. The monarchy would remain held by the Wittelsbachs until the kingdom's dissolution in 1918. Most of Bavaria's modern-day borders were established after 1814 with the Treaty of Paris, in which Bavaria ceded Tyrol and Vorarlberg to the Austrian Empire while receiving Aschaffenburg and parts of Hesse-Darmstadt. As a state within the German Empire, the kingdom was second in size only to the Kingdom of Prussia. Since the unification of Germany in 1871, Bavaria has remained part of Germany.

History

Foundation

On 30 December 1777, the Bavarian line of the Wittelsbachs became extinct, and the succession on the Electorate of Bavaria passed to Charles Theodore, the elector palatine. After a separation of four and a half centuries, the Palatinate, to which the duchies of Jülich and Berg had been added, was thus reunited with Bavaria. In 1792 French revolutionary armies overran the Palatinate; in 1795 the French, under Moreau, invaded Bavaria itself, advanced to Munich — where they were received with joy by the long-suppressed Liberals — and laid siege to Ingolstadt. Charles Theodore, who had done nothing to prevent wars or to resist the invasion, fled to Saxony, leaving a regency, the members of which signed a convention with Moreau, by which he granted an armistice in return for a heavy contribution (7 September 1796). Between the French and the Austrians, Bavaria was now in a bad situation. Before the death of Charles Theodore (16 February 1799) the Austrians had again occupied the country, in preparation for renewing the war with France.

Maximilian IV Joseph (of Zweibrücken), the new elector, succeeded to a difficult inheritance. Though his own sympathies, and those of his all-powerful minister, Maximilian von Montgelas, were, if anything, French rather than Austrian, the state of the Bavarian finances, and the fact that the Bavarian troops were scattered and disorganized, placed him helpless in the hands of Austria; on 2 December 1800 the Bavarian arms were involved in the Austrian defeat at Hohenlinden, and Moreau once more occupied Munich. By the Treaty of Lunéville (9 February 1801) Bavaria lost the Palatinate and the duchies of Zweibrücken and Jülich. In view of the scarcely disguised ambitions and intrigues of the Austrian court, Montgelas now believed that the interests of Bavaria lay in a frank alliance with the French Republic; he succeeded in overcoming the reluctance of Maximilian Joseph; and, on 24 August, a separate treaty of peace and alliance with France was signed at Paris.

The 1805 Peace of Pressburg recognized Maximilian I's claim to be King of Bavaria. The elector declared himself to be king on 1 January 1806, officially changing the Electorate of Bavaria to being the Kingdom of Bavaria. The King still served as an Elector until Bavaria left the Holy Roman Empire (1 August 1806). The duchy of Berg was ceded to Napoleon only in 1806. The new kingdom faced challenges from the outset of its creation, relying on the support of Napoleonic France and having to change its constitution in accordance with France's wishes. The kingdom faced war with Austria in 1808 and from 1810 to 1814, lost territory to Württemberg, Italy, and then Austria.

However with the defeat of Napoleon's France in 1814, Bavaria was compensated for some of its losses, and received new territories such as the Grand Duchy of Würzburg, the Archbishopric of Mainz (Aschaffenburg), parts of the Grand Duchy of Hesse, and in 1816, the Rhenish Palatinate from France.

Between 1799 and 1817 the leading minister Count Montgelas followed a strict policy of modernisation and laid the foundations of administrative structures that survived even the monarchy and are (in their core) valid until today. On 1 February 1817, Montgelas had been dismissed; and Bavaria had entered on a new era of constitutional reform.

Constitution

On 26 May 1818, the constitution of the Kingdom of Bavaria was proclaimed. The Landtag would have two houses, an upper house (Herrenhaus) comprising the aristocracy and noblemen, including the high-class hereditary landowners, government officials and nominees of the crown. The second house, a lower house (Abgeordnetenhaus), would include representatives of small landowners, the towns and the peasants. The rights of Protestants were safeguarded in the constitution with articles supporting the equality of all religions, despite opposition by supporters of the Roman Catholic Church. The initial constitution almost proved disastrous for the monarchy, with controversies such as the army having to swear allegiance to the new constitution. The monarchy appealed to the Kingdom of Prussia and the Austrian Empire for advice, the two refused to take action on Bavaria's behalf, but the debacles lessened and the state stabilized with the accession of Ludwig I to the throne following the death of Maximilian in 1825.

Ludwig I, Maximilian II and the Revolutions

In 1825, Ludwig I ascended to the throne of Bavaria. Under Ludwig, the arts flourished in Bavaria, and Ludwig personally ordered and financially assisted the creation of many neoclassical buildings and architecture across Bavaria. Ludwig also increased Bavaria's pace towards industrialization under his reign. In foreign affairs under Ludwig's rule, Bavaria supported the Greeks during the Greek War of Independence with his second son, Otto being elected King of Greece in 1832. As for politics, initial reforms advocated by Ludwig were both liberal and reform-oriented. However, after the Revolutions of 1830, Ludwig turned to conservative reaction. In 1837, the Roman Catholic-supported clerical movement, the Ultramontanes, came to power in the Bavarian parliament and began a campaign of reform to the constitution, which removed civil rights that had earlier been granted to Protestants, as well as enforcing censorship and forbidding the free discussion of internal politics. This regime was short-lived due to the demand by the Ultramontanes of the naturalization of Ludwig I's Irish mistress, which was resented by Ludwig, and the Ultramontanes were pushed out.

Following the Revolutions of 1848 and Ludwig's low popularity, Ludwig I abdicated the throne to avoid a potential coup, and allowed his son, Maximilian II, to become the King of Bavaria. Maximilian II responded to the demands of the people for a united German state by attending the Frankfurt Assembly, which intended to create such a state. Maximilian II stood alongside Bavaria's ally, the Austrian Empire, in opposition to Austria's enemy, the Kingdom of Prussia, which was to receive the imperial crown of a united Germany. This opposition was resented by many Bavarian citizens, who wanted a united Germany, but in the end Prussia declined accepting the crown and the constitution of a German state they perceived to be too liberal and not in Prussia's interests.

In the aftermath of the failure of the Frankfurt Assembly, Prussia and Austria continued to debate over which monarchy had the inherent right to rule Germany. A dispute between Austria and the Electoral Prince of Hesse-Kassel (or Hesse-Cassel) was used by Austria and its allies (including Bavaria) to promote the isolation of Prussia in German political affairs. This diplomatic insult almost led to war when Austria, Bavaria and other allies moved troops through Bavaria towards Hesse-Kassel in 1850. However the Prussian army backed down to Austria and caved in to the acceptance of dual leadership. This event was known as the Punctation of Olmütz but also known as the "Humiliation of Olmütz" by Prussia. This event solidified the Bavarian kingdom's alliance with Austria against Prussia. Attempts by Prussia to reorganize the loose and un-led German Confederation were opposed by Bavaria and Austria, with Bavaria taking part in its own discussions with Austria and other allies in 1863, in Frankfurt, without Prussia and its allies attending.

Austro-Prussian War

In 1864, Maximilian II died early, and his eighteen year-old son, Ludwig II, arguably the most famous of the Bavarian kings, became King of Bavaria as escalating tensions between Austria and Prussia grew steadily. Prussia's Minister-President Otto von Bismarck, recognizing the immediate likelihood of war, attempted to sway Bavaria towards neutrality in the conflict. Ludwig II refused Bismarck's offers and continued Bavaria's alliance with Austria. In 1866, violence erupted between Austria and Prussia and the Austro-Prussian War began. Bavaria and most of the south German states, with the exception of Austria and Saxony, contributed far less to the war effort against Prussia. Austria quickly faltered after its defeat at the Battle of Königgrätz and was totally defeated shortly afterward. Austria was humiliated by defeat and was forced to concede control, and its sphere of influence, over the south German states. Bavaria was spared harsh terms in the peace settlement, however from this point on it and the other south German states steadily progressed into Prussia's sphere of influence.

Ludwig II and the German Empire

With Austria's defeat in the Austro-Prussian War, the northern German states quickly unified into the North German Confederation, with Prussia's King leading the state. Bavaria's previous inhibitions towards Prussia changed, along with those of many of the south German states, after French emperor Napoleon III began speaking of France's need for "compensation" from its loss in 1814 and included Bavarian-held Palatinate as part of its territorial claims. Ludwig II joined an alliance with Prussia, in 1870, against France, which was seen by Germans as the greatest enemy to a united Germany. At the same time, Bavaria increased its political, legal, and trade ties with the North German Confederation. In 1870, war erupted between France and Prussia in the Franco-Prussian War. The Bavarian Army was sent under the command of the Prussian crown prince against the French army.

With France's defeat and humiliation against the combined German forces, it was Ludwig II who proposed that Prussian King Wilhelm I be proclaimed German Emperor or "Kaiser" of the German Empire ("Deutsches Reich"), which occurred in 1871 in German occupied Versailles, France. The territories of the German Empire were declared, which included the states of the North German Confederation and all of the south German states, with the major exception of Austria. The Empire also annexed the formerly French territory of Alsace-Lorraine, due in large part to Ludwig's desire to move the French frontier away from the Palatinate.

Bavaria's entry into the German Empire changed, from jubilation over France's defeat, to dismay shortly afterward, over the direction of Germany under the new German Chancellor and Prussian Prime Minister, Otto von Bismarck. The Bavarian delegation under Count Otto von Bray-Steinburg had secured a privileged status of the Kingdom of Bavaria within the German Empire (Reservatrechte). Within the Empire the Kingdom of Bavaria was even able to retain its own diplomatic body and its own army, which would fall under Prussian command only in times of war.

In the years following German unification, Bismarck initiated a persecution of the Catholic Church in the so-called Kulturkampf. Although this persecution was limited to Prussia and never extended to Bavaria or the other predominantly Catholic southern German states, it caused considerable estrangement between Bavaria and Prussia. Due in part to co-operation between the Bavarian Patriotic Party and German Centre Party in the Reichstag, Bismarck was eventually compelled to moderate his anti-Catholic policies.

After Bavaria's unification into Germany, Ludwig II became increasingly detached from Bavaria's political affairs and spent vast amounts of money on personal projects, such as the construction of a number of fairytale-like castles and palaces, the most famous being the Wagnerian-style Castle Neuschwanstein. Although Ludwig used his personal wealth to finance these projects instead of state funds, the construction projects landed him deeply in debt. These debts caused much concern among Bavaria's political elite, who sought to persuade Ludwig to cease his building; he refused, and relations between the government's ministers and the crown deteriorated.

At last, in 1886, the crisis came to a head: the Bavarian ministers deposed the king, organizing a medical commission to declare him insane, and therefore incapable of executing his governmental powers. A day after Ludwig's deposition, the king died mysteriously after asking the commission's chief psychiatrist to go on a walk with him along Lake Starnberg (then called Lake Würm). Ludwig and the psychiatrist were found dead, floating in the lake. An autopsy listed cause of death as suicide by drowning, but some sources claim that no water was found in Ludwig's lungs. While these facts could be explained by dry drowning, they have also led to some conspiracy theories of political assassination.

Regency

The crown passed to Ludwig's brother Otto I, but since Otto had a clear history of mental illness, the duties of the throne actually rested in the hands of the brothers' uncle, Prince Luitpold, serving as regent.

During the regency of Prince-Regent Luitpold, from 1886 to 1912, relations between Bavarians and Prussians remained cold, with Bavarians remembering the anti-Catholic agenda of Bismarck's Kulturkampf, as well as Prussia's strategic dominance over the empire. Bavaria protested Prussian dominance over Germany and snubbed the Prussian-born German Emperor, Wilhelm II, in 1900, by forbidding the flying of any other flag other than the Bavarian flag on public buildings for the Emperor's Birthday, but this was swiftly modified afterwards, allowing the German imperial flag to be hung side by side with the Bavarian flag. With the Centre politician Georg von Hertling the Prince-Regent appointed to the head of government for the first time a representative of the Landtag's majority.

In 1912, Luitpold died, and his son, Prince-Regent Ludwig, took over as regent of Bavaria. A year later, the regency ended when Ludwig declared himself King of Bavaria and from that point on was known as Ludwig III.

World War I and the end of the Kingdom

In 1914, a clash of alliances occurred over Austria-Hungary's invasion of Serbia following the assassination of Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand by a Bosnian Serb militant. Germany went to the side of its former rival-turned-ally, Austria-Hungary, while France, Russia, and the United Kingdom declared war on Austria-Hungary and Germany. Initially, in Bavaria and all across Germany, recruits flocked enthusiastically to the German Army. At the outbreak of World War I King Ludwig III sent an official dispatch to Berlin to express Bavaria's solidarity. Later Ludwig even claimed annexations for Bavaria (Alsace and the city of Antwerp in Belgium, to receive an access to the sea). His hidden agenda was to maintain the balance of power between Prussia and Bavaria within the German Empire after a victory. Over time, with a stalemated and bloody war on the western front, Bavarians, like many Germans, grew weary of a continuing war.

In 1917, when Germany's situation had gradually worsened due to World War I, the Bavarian Prime Minister Georg von Hertling became German Chancellor and Prime Minister of Prussia and Otto Ritter von Dandl was made new Prime Minister of Bavaria. Accused of showing blind loyalty to Prussia, Ludwig III became increasingly unpopular during the war. In 1918, the kingdom attempted to negotiate a separate peace with the allies but failed. By 1918, civil unrest was spreading across Bavaria and Germany; Bavarian defiance to Prussian hegemony and Bavarian separatism being key motivators. In November 1918, William II abdicated the throne of Germany, and Ludwig III, along with the other German monarchs, issuing the Anif declaration, followed in abdication shortly afterwards. With this, the Wittelsbach dynasty came to an end, and the former Kingdom of Bavaria became the Free State of Bavaria, which it is still named today. The funeral of Lugwig III in 1921 was feared or hoped to spark a restoration of the monarchy. Despite the abolition of the monarchy, the former King was laid to rest in front of the royal family, the Bavarian government, military personnel, and an estimated 100,000 spectators, in the style of royal funerals. Prince Rupprecht did not wish to use the occasion of the passing of his father to reestablish the monarchy by force, preferring to do so by legal means. Michael von Faulhaber, Archbishop of Munich, in his funeral speech, made a clear commitment to the monarchy while Rupprecht only declared that he had stepped into his birthright.[1]

Geography, administrative regions and population

When Napoleon abolished the Holy Roman Empire, and Bavaria became a kingdom in 1806, its area reduplicated. Tyrol (1805–1814) and Salzburg (1810–1815) were temporarily reunited with Bavaria but finally ceded to Austria. In return the Rhenish Palatinate and Franconia were annexed to Bavaria in 1815.

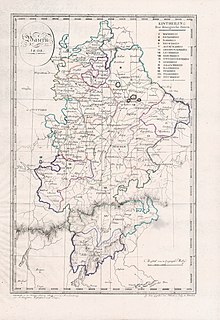

The Kingdom of Bavaria was divided from 1837 into 8 administrative regions called Regierungsbezirke (singular Regierungsbezirk). The regions ("Kreis") were named after its main rivers before, but King Ludwig I reorganized the administrative regions of Bavaria in 1837 and re-introduced the old names Upper Bavaria, Lower Bavaria, Franconia, Swabia, Upper Palatinate and Palatinate. He changed his royal titles to Ludwig, King of Bavaria, Duke of Franconia, Duke in Swabia and Count Palatinate of the Rhine. His successors kept these titles. Ludwig's plan to reunite also the eastern part of the Palatinate with Bavaria could not be realized. The Electorate of the Palatinate, a former dominion of the Wittelsbach, had been split up in 1815, the eastern bank of the Rhine with Mannheim and Heidelberg was given to Baden, only the western bank was granted to Bavaria. Here Ludwig founded the city of Ludwigshafen as a Bavarian rival to Mannheim.

After the lost Austro-Prussian War (1866) the Kingdom of Bavaria had to cede several Lower Franconian districts to Prussia. The duchy of Coburg was never part of the Kingdom of Bavaria since it was united with Bavaria only in 1920. Also Ostheim was added to Bavaria (1945) after the end of the monarchy.

Statistics

- Area = 75,865 km² (1900)

- Population = 3,707,966 (1818) / 4,370,977 (1840) / 6,176,057 (1900) / 6,524,372 (1910)

- Regions (1806–1837):

- Altmühlkreis (1806-1810 / dissolved)

- Eisackkreis (1806-1810 / ceded to Italy)

- Etschkreis (1806-1810 / ceded to Italy)

- Illerkreis (1806-1817 / dissolved)

- Innkreis (1806-1814 / ceded to Austria)

- Isarkreis (1806–1837 / transformed into Upper Bavaria)

- Lechkreis (1806-1810 / dissolved)

- Mainkreis (1806–1837 / transformed into Upper Franconia)

- Naabkreis (1806-1810 / dissolved)

- Oberdonaukreis (1806–1837 / transformed into Lower Bavaria)

- Pegnitzkreis (1806-1810 / dissolved)

- Regenkreis (1806–1837 / transformed into Upper Palatinate)

- Rezatkreis (1806–1837 / transformed into Middle Franconia)

- Rheinkreis (1815-1837 / transformed into Palatinate)

- Salzachkreis (1810–1815 / ceded to Austria)

- Unterdonaukreis (1806–1837 / transformed into Swabia)

- Untermainkreis (1817-1837 / transformed into Lower Franconia )

- Regions (1837–1918):

- Upper Franconia (German: Oberfranken) (Capital:Bayreuth)

- Middle Franconia ([Mittelfranken] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)) (Capital:Ansbach)

- Lower Franconia ([Unterfranken] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)) (Capital:Würzburg)

- Swabia ([Schwaben] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)) (Capital:Augsburg)

- Palatinate ([Pfalz] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)) (Capital:Speyer)

- Upper Palatinate ([Oberpfalz] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)) (Capital:Regensburg)

- Upper Bavaria ([Oberbayern] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)) (Capital:Munich)

- Lower Bavaria ([Niederbayern] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)) (Capital:Landshut)

See also

- King of Bavaria

- List of Minister-Presidents of Bavaria

- Bavaria

- History of Bavaria

- History of Germany

External links

![]() Media related to Kingdom of Bavaria at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Kingdom of Bavaria at Wikimedia Commons

- ^ Beisetzung Ludwigs III., München, 5. November 1921 Template:De icon Historisches Lexikon Bayerns – Funeral of Ludwig III, accessed: 1 July 2011