Eastern Bloc economies: Difference between revisions

Ceaușescu |

→Housing quality: Making changes according to cited source, see talk page. |

||

| Line 458: | Line 458: | ||

|align=left|[[People's Republic of Poland|Poland]] || 50.0% (1980) || 47.3% || 22.2% || 33.4% || 83.0% |

|align=left|[[People's Republic of Poland|Poland]] || 50.0% (1980) || 47.3% || 22.2% || 33.4% || 83.0% |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|align=left|[[People's Republic of Romania|Romania]] || 50.0% (1980) || |

|align=left|[[People's Republic of Romania|Romania]] || 50.0% (1980) || 12.3% (1966) || n/a || n/a || 81.5% |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|align=left|Soviet Union || 50.0% (1980) || n/a || n/a || n/a || n/a |

|align=left|Soviet Union || 50.0% (1980) || n/a || n/a || n/a || n/a |

||

Revision as of 23:29, 16 May 2012

The examples and perspective in this article may not include all significant viewpoints. (May 2010) |

| Eastern Bloc |

|---|

|

After the Soviet Union's occupation of much of the Eastern Bloc during World War II, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin implemented socioeconomic transformations of each of the Eastern Bloc economies that comported with the Soviet Communist economic model. As with the economy of the Soviet Union, government planners in the Eastern bloc were directed by the resulting Five Year Plans which followed paths of extensive rather than intensive development, focusing upon heavy industry as the Soviet Union had done, leading to inefficiencies and shortage economies.[1]

Agricultural collectivization proceeded more smoothly in the Eastern Bloc satellite states than it had in the Soviet Union. Severe stagnation in economic growth occurred, with Eastern Bloc economies lagging far behind their western European counterparts. Housing shortages also arose, which led to the erection of large quantities of often substandard pre-fabricated apartment blocks.

Background

Creation of the Eastern Bloc

Bolsheviks took power following the Russian Revolution of 1917. During the Russian Civil War that followed, coinciding with the Red Army's entry into Minsk in 1919, Belarus was declared the Socialist Soviet Republic of Byelorussia. After more conflict, the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic was declared in 1920. With the defeat of the Ukraine in the Polish-Ukrainian War, after the March 1921 Peace of Riga following the Polish-Soviet War, central and eastern Ukraine were annexed into the Soviet Union as the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. In 1922, the Russian SFSR, Ukraine SSR, Byelorussian SSR and Transcaucasian SFSR were officially merged as republics creating the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, or Soviet Union.

At the end of World War II, all eastern and central European capitals were controlled by the Soviet Union.[2] During the final stages of the war, the Soviet Union began the creation of the Eastern Bloc by directly annexing several countries as Soviet Socialist Republics that were originally effectively ceded to it by Nazi Germany in the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact.

These included Eastern Poland (incorporated into the Ukrainian and Byelorussian SSRs),[3] Latvia (became Latvia SSR),[4][5] Estonia (became Estonian SSR),[4][5] Lithuania (became Lithuania SSR),[4][5] part of eastern Finland (became Karelo-Finnish SSR)[6] and northeastern Romania (part of which became the Moldavian SSR).[7][8]

By 1945, these additional annexed countries totaled approximately 180,000 additional square miles, or slightly more than the area of West Germany, East Germany and Austria combined.[9] Other states were converted into Soviet Satellite states, such as the People's Republic of Poland, the People's Republic of Hungary,[10] the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic,[11] the People's Republic of Romania, the People's Republic of Albania,[12] and later East Germany from the Soviet zone of German occupation.[13] The Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia was also sometimes considered part of the Bloc, although not participating in either Warsaw Pact or COMECON,[14][15] though a Tito-Stalin split occurred in 1948[16] followed by the formation of the Non-Aligned Movement.

Conditions in the Eastern Bloc

As a consequence of German and Soviet aggression in Eastern Europe, much of the region was subjected to enormous destruction of industry, infrastructure and loss of civilian life. In Poland alone the policy of plunder and exploitation inflicted enormous material losses to Polish industry (62% of which was destroyed)[17]), agriculture, infrastructure and cultural landmarks, the cost of which has been estimated as approximately €525 billion or $640 billion in 2004 exchange values[18] Post-war reconstruction was also hampered by the loss of 6 million citizens during the war, many of whom were highly educated professionals[19][20]. In the USSR, where over 27 million people had lost their lives as a result of the Nazi invasion, material losses were also immense, with whole villages burnt to the ground and many urban areas reduced to the rubble. In general, Eastern Europe emerged as more devastated by the war, than Western Europe[21]

Throughout the Eastern Bloc, both in the Soviet Socialist Republic and the rest of the Bloc, Russia was given prominence, and referred to as the naibolee vydajuščajasja nacija (the most prominent nation) and the rukovodjaščij narod (the leading people).[9] The Soviets promoted the reverence of Russian actions and characteristics, and the construction of Soviet Communist structural hierarchies in the other countries of the Eastern Bloc.[9]

The defining characteristic of communism implemented in the Eastern Bloc was the unique symbiosis of the state with society and the economy, resulting in politics and economics losing their distinctive features as autonomous and distinguishable spheres.[22] Initially, Stalin directed systems that rejected Western institutional characteristics of market economies, democratic governance (dubbed "bourgeois democracy" in Soviet parlance) and the rule of law subduing discretional intervention by the state.[23]

The Soviets mandated expropriation and etatization of private property.[24] The Soviet-style "replica regimes" that arose in the Bloc not only reproduced Soviet command economies, but also adopted the brutal methods employed by Joseph Stalin and Soviet secret police to suppress real and potential opposition.[24]

Communist regimes in the Eastern Bloc saw even marginal groups of opposition intellectuals as a potential threat because of the bases underlying Communist power therein.[25] The suppression of dissidence and opposition was a central prerequisite for the security of Communist power within the Eastern Bloc, though the degree of opposition and dissident suppression varied by country and time throughout the Eastern Bloc.[25]

In addition, media in the Eastern Bloc were organs of the state, completely reliant on and subservient to the Communist Party, with radio and television organizations being state-owned, while print media was usually owned by political organizations, mostly by the local Communist Party.[26] While over 15 million Eastern Bloc residents migrated westward from 1945 to 1949,[27] emigration was effectively halted in the early 1950s, with the Soviet approach to controlling national movement emulated by most of the rest of the Eastern Bloc.[28]

Initial changes

Transformations billed as reforms

For Soviet Socialist Republics, because of strict Soviet secrecy under Joseph Stalin, for many years after World War II, even the best informed foreigners did not effectively know about the operation of the Soviet economy.[29] Stalin had sealed off outside access to the Soviet Union since 1935 (and until his death), effectively permitting no foreign travel inside the Soviet Union such that outsiders did not know of the political processes that had taken place therein.[30] During this period, and even for 25 years after Stalin's death, the few diplomats and foreign correspondents permitted inside the Soviet Union were usually restricted to within a few miles of Moscow, their phones were tapped, their residences were restricted to foreigner-only locations and they were constantly followed by Soviet authorities.[30]

The Soviets also modeled economies in the rest of Eastern Bloc outside the Soviet Union along Soviet command economy lines.[31] Before World War II, the Soviet Union used draconian procedures to ensure compliance with directives to invest all assets in state planned manners, including the collectivisation of agriculture and utilizing a sizeable labor army collected in the gulag system.[32] This system was largely imposed on other Eastern Bloc countries after World War II.[32] While propaganda of proletarian improvements accompanied systemic changes, terror and intimidation of the consequent ruthless Stalinism obfuscated feelings of any purported benefits.[33]

Stalin felt that socioeconomic transformation was indispensable to establish Soviet control, reflecting the Marxist-Leninist view that material bases, the distribution of the means of production, shaped social and political relations.[34] Moscow trained cadres were put into crucial power positions to fulfill orders regarding sociopolitical transformation.[34] Elimination of the bourgeoisie's social and financial power by expropriation of landed and industrial property was accorded absolute priority.[35] These measures were publicly billed as reforms rather than socioeconomic transformations.[35] Throughout the Eastern Bloc, except for Czechoslovakia, "societal organizations" such as trade unions and associations representing various social, professional and other groups, were erected with only one organization for each category, with competition excluded.[35] Those organizations were managed by communist cadres, though during the initial period, they allowed for some diversity.[36]

Asset relocation

At the same time, at the war's end, the Soviet Union adopted a "plunder policy" of physically transporting and relocating east European industrial assets to the Soviet Union.[37] Eastern Bloc states were required to provide coal, industrial equipment, technology, rolling stock and other resources to reconstruct the Soviet Union.[38] Between 1945 and 1953, the Soviets received a net transfer of resources from the rest of the Eastern Bloc under this policy of roughly $14 billion, an amount comparable to the net transfer from the United States to western Europe in the Marshall Plan.[38][39] "Reparations" included the dismantling of railways in Poland and Romanian reparations to the Soviets between 1944-48 valued at $1.8 billion concurrent with the domination of SovRoms.[32]

In addition, the Soviets reorganized enterprises as joint-stock companies in which the Soviets possessed the controlling interest.[39][40] Using that control vehicle, several enterprises were required to sell products at below world prices to the Soviets, such as uranium mines in Czechoslovakia and East Germany, coal mines in Poland, and oil wells in Romania.[41]

Trade and COMECON

The trading pattern of the Eastern Bloc countries was severely modified.[42] Before World War II, no greater than 1% – 2% of those countries' trade was with the Soviet Union.[42] By 1953, share of such trade had jumped from to 37%.[42] In 1947, Stalin had also denounced the Marshall Plan and forbade all Eastern Bloc countries from participating in it.[43]

Soviet dominance further tied other Eastern Bloc economies, except for Yugoslavia,[42] to Moscow via the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (CMEA) or COMECON, which determined countries' investment allocations and the products that would be traded within Eastern Bloc.[44] Although COMECON was initiated in 1949, its role became ambiguous because Stalin preferred more direct links with other party chiefs than the indirect sophistication of the Council; it played no significant role in the 1950s in economic planning.[45]

Initially, COMECON served as cover for the Soviet taking of materials and equipment from the rest of the Eastern Bloc, but the balance changed when the Soviets became net subsidizers of the rest of the Bloc by the 1970s via an exchange of low cost raw materials in return for shoddily manufactured finished goods.[46] While resources such as oil, timber and uranium initially made gaining access to other Eastern Bloc economies attractive, the Soviets soon had to export Soviet raw materials to those countries to maintain cohesion therein.[32] Following resistance to COMECON plans to extract Romania's mineral resources and heavily utilize its agricultural production, in 1964 Romania began to take a more independent stance.[47] While it did not repudiate COMECON, it took no significant role in its operation, especially after the rise to power of Nicolae Ceauşescu.[47]

Command economy elements

Five Year Plans

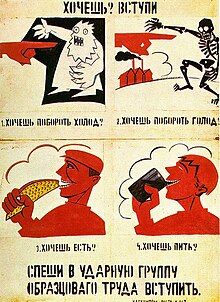

"1. You want to overcome cold?

2. You want to overcome hunger?

3. You want to eat?

4. You want to drink?

Hurry to enter shock brigades!"

Economic activity was governed by Five year plans, divided into monthly segments, with government planners frequently attempting to meet plan targets regardless of whether a market existed for the goods being produced.[48] Little coordination existed between departments such that cars could be produced before filling stations or roads were built, or a new hospital in Warsaw in the 1980s could stand empty for four years waiting for the production of equipment to fill it.[48] Nevertheless, if such political objectives had been met, propagandists could boast of increased vehicle production and the completion of another new hospital.[48]

Inefficient bureaucracies were frequently created, with for instance, Bulgarian farms having to meet at least six hundred different plan fulfillment figures.[48] Socialist product requirements produced distorted black market consequences, such that broken light bulbs possessed significant market values in Eastern Bloc offices because a broken light bulb was required to be submitted before a new light bulb would be issued.[49]

Factory managers and foremen could hold their posts only if they were cleared under the nomenklatura list system of communist party-approved cadres.[49] All decisions were constrained by the party politics of what was considered good management.[49] For laborers, work was assigned on the pattern of "norms", with sanctions for non-fulfillment.[49] However, the system really served to increase inefficiency, because if the norms were met, management would merely increase them.[49] The stakhanovite system was employed to highlight the achievements of successful work brigades, and "shock brigades" were introduced into plants to show the others how much could be accomplished.[49]

Also, "Lenin shifts" or "Lenin Saturdays" were introduced, requiring extra work time for no pay.[50] However, the emphasis on the construction of heavy industry provided full employment and social mobility through the recruitment of young rural workers and women.[51] While blue-collar workers enjoyed that they earned as much or more than many professionals, the standard of living did not match the pace of improvement in Western Europe.[51]

Only Yugoslavia (and later Romania and Albania) engaged in their own industrial planning, though they enjoyed little more success than that of the rest of the Bloc.[44] Albania, which had remained strongly Stalinist in ideology well after de-Stalinization, was politically and commercially isolated from the other Eastern Bloc countries and the west.[52] By the late 1980s, it was the poorest country in Europe, and still lacked sewerage, piped water, and piped gas.[52]

Heavy industry emphasis and shortage economies

Because of the lack of market signals in such economies, they experienced mis-development by central planners resulting in those countries following a path of extensive (large mobilization of inefficiently used capital, labor, energy and raw material inputs) rather than intensive (efficient resource use) development to attempt to achieve quick growth.[53][54] The Eastern Bloc countries were required to follow the Soviet model overemphasizing heavy industry at the expense of light industry and other sectors.[49]

Since that model involved the prodigal exploitation of natural and other resources, it has been described as a kind of "slash and burn" modality.[54] While the Soviet system strove for a dictatorship of the proletariat, there was little existing proletariat in many eastern European countries, such that to create one, heavy industry needed to be built.[49] Each system shared the distinctive themes of state-oriented economies, including poorly defined property rights, a lack of market clearing prices and overblown or distorted productive capacities in relation to analogous market economies.[22]

Major errors and waste occurred in the over-centralized resource allocation and distribution systems.[55] Because of the party-run monolithic state organs, these systems provided no effective mechanisms or incentives to control costs, profligacy, inefficiency and waste.[55] Heavy industry was given priority because of its importance for the military-industrial establishment and for the engineering sector.[56]

Factories were sometimes inefficiently located, incurring high transport costs, while poor plant organization sometimes resulted in production hold ups and knock-on effects in other industries dependent on monopoly suppliers of intermediates.[57] For example, each country, including Albania, built steel mills regardless of whether they lacked the requisite resource of energy and mineral ores.[49] A massive metallurgical plant was built in Bulgaria despite that its ores had to be imported from the Soviet Union and carried for 200 miles from the port at Burgas.[49] A Warsaw tractor factory in 1980 had a 52 page list of unused rusting, then useless, equipment.[49]

The emphasis on heavy industry diverted investment from the more practical production of chemicals and plastics.[44] In addition, the plans' emphases on quantity rather than quality made Eastern Bloc products less competitive in the world market.[44] High costs passed though the product chain boosted the 'value' of production on which wage increases were based, but made exports less competitive.[57] Planners rarely closed old factories even when new capacities opened elsewhere.[57]

For example, the Polish steel industry retained a plant in Upper Silesia despite the opening of modern integrated units on the periphery while the last old Siemens-Martin process furnace installed in the 19th century was not closed down immediately.[57]

Producer goods were favored over consumer goods, causing consumer goods to be lacking in quantity and quality in the shortage economies that resulted.[54][54][58]

By the mid-1970s, budget deficits rose considerably and domestic prices widely diverged from the world prices, while production prices averaged 2% higher than consumer prices.[59] Many premium goods could be bought only in special stores using foreign currency generally inaccessible to most Eastern Bloc citizens, such as Intershop in East Germany,[60] Beryozka in the Soviet Union,[61] Pewex in Poland,[62][63] Tuzex in Czechoslovakia[64] and Corecom in Bulgaria. Much of what was produced for the local population never reached its intended user, while many perishable products became unfit for consumption before reaching their consumers.[55]

Moreover, Stasi reports complained about individuals who had been given privileged access to travel to the West for work with "stories of the 'overwhelming range of commodities available . . . or with reports of East German goods on sale there at knock-down prices."[65] Resulting consumer good shortages, in some cases, distorted non-market behavior, such as in Czechoslovakia, where abortion became the most common form of contraception because periodic shortages of birth control pills and intrauterine devices made these systems unreliable.[66]

Black markets

As a result, black markets were created that were often supplied by goods stolen from the public sector.[50][67] A saying in Czechoslovakia was "if you do not steal from the state, you are robbing your own family."[50] This second "parallel economy" flourished throughout the Bloc because of rising unmet state consumer needs.[68] Black and gray markets for foodstuffs, goods, and cash arose.[68] Goods included household goods, medical supplies, clothes, furniture, cosmetics, and toiletries in chronically short supply through official outlets.[63]

Many farmers concealed actual output from purchasing agencies to sell it illicitly to urban consumers.[63] Hard foreign currencies were highly sought after, while highly valued Western items functioned as a medium of exchange or bribery in Communist countries, such as in Romania, where Kent cigarettes served as an unofficial extensively used currency to buy goods and services.[69] Some service workers "moonlighted" illegally providing services directly to customers for payment.[69]

Urbanization

The extensive production industrialization that resulted was not responsive to consumer needs and caused a neglect in the service sector, unprecedented rapid urbanization, acute urban overcrowding, chronic shortages and massive recruitment of women into mostly menial and/or low-paid occupations.[55] The consequent strains resulted in the widespread used of coercion, repression, show trials, purges and intimidation.[55] By 1960, massive urbanization occurred in Poland (48% urban) and Bulgaria (38%), which increased employment for peasants, but also caused illiteracy to skyrocket when children left school for work.[55]

Cities became massive building sites, resulting in the reconstruction of some war-torn buildings but also the construction of drab dilapidated system-built apartment blocks.[55] Urban living standards plummeted because resources were tied up in huge long-term building projects, while industrialization forced millions of former peasants to live in hut camps or grim apartment blocks close to massive polluting industrial complexes.[55]

Purges and protest

While unable to effectuate substantial change, workers sometimes expressed rising discontent over stagnating standards of living through informal means such as slowdowns at the workplace, high rates of absenteeism, and cynicism about promises of socialist gains.[51] Worker participation in official activities and organizations diminished.[51] As economic growth slowed, demands for more and better consumer goods mushroomed.[51] Broad social purges were often carried out to control discontent, but they also caused severe economic dislocations.[70] The purges often coincided with the introduction of the first Five Year Plans in the non-Soviet members of the Eastern Bloc.[71]

The objectives of the plans were considered beyond political reproach even when such objectives were irrational, such that workers that did not fulfill targets were targeted and blamed for economic woes, while at the same time, the ultimate responsibility for the economic shortcomings would be placed on prominent victims of the political purge.[71] In Romania, Gheorghiu-Dej admitted that 80,000 peasants had been accused of siding with the class enemy because they resisted collectivization, while purged party elite Ana Pauker was blamed for this "distortion".[71]

Huge construction projects were launched with insufficient capital such that unpaid prisoners sometimes had to serve in place of modern equipment.[70] Disruption of the trained administrative and management elites also caused harm.[70] So many workers were dismissed from established professions in purges that they often had to be replaced by hastily trained younger workers, who did not possess questionable class origins.[70] A Czechoslovakian noted:[70]

The highly qualified professional people are laying roads, building bridges and operating machines, and the dumb clots—whose fathers used to dig, sweep or bricklay—are on top, telling the others where to lay the roads, what to produce and how to spend the country's money. The consequence is the roads look like plowed fields, we make things we can’t sell and the bridges can’t be used for traffic…. Then they wonder why the economy is going downhill like a ten-ton lorry with the brakes off.

Isolation and planned career progressions were frequent. For example, when a British student asked one of the few Romanians who would approach him why Romanians did not attend the summer schools complex at which he was staying, he laughed, looked around to see that he was not being watched and responded "You see, we live in a Socialist country and here the state maps out your life for you from birth. You are assigned a school, you are assigned a job and you are assigned a place to live. Conformity is the rule, you do what you are told and if your expectations are limited and you don't step out of line, then you will be satisfied. And to make sure that you don't step out of line they have the Securitate."[72]

At times, the moving "norm" requirements of plans provoked overt public outrage. In 1953, with East Germany already losing tremendous numbers of its citizens through the only "loophole" in the Eastern Bloc emigration restrictions—the Berlin sector border—the East German government raised "norms" by 10%.[73] When a union newspaper printed this, the already disaffected remaining East German population that could view the relative economic successes of West Germany across the Berlin city sector border became enraged.[73]

In what was termed the Uprising of 1953 in East Germany, angry building workers on construction sites initiated street protests, and were soon joined by others in a march to the trade union headquarters.[73] While no official spoke to them there, by 2:00 p.m., the East German government agreed to withdraw the "norm" increases.[74] The crisis had already escalated to the point where the demands were now political, including free elections, disbanding of the army and resignation of the government.[74] Within one week, strikes were recorded in 317 locations involving approximately 400,000 workers.[74] When strikers set ruling SED party buildings aflame and tore the flag from the Brandenburg Gate, SED General Secretary Walter Ulbricht decided to leave Berlin.[74]

A major emergency was declared and the Soviet Red Army stormed some important buildings.[74] A few hours later, tanks were employed, but they did not fire upon workers.[74] Rather, a gradual pressure was applied.[74] However, bloodshed could not be entirely avoided, with the official death toll standing at 21, while it was more likely much higher.[74] Thereafter, 20,000 arrests took place along with 40 executions.[74]

With the exception of Poland, labor discontent never reached a point where it threatened to overturn the ruling regimes.[51] But ruling Communists toward the end of the Eastern Bloc's existence never again were able to command the loyalty they attained in the early postwar period.[51] When Communist governments finally toppled in 1989, labor disaffection was apparent and workers in no country rose to defend falling regimes.[51]

Agricultural collectivization

Collectivization is a process pioneered by Joseph Stalin in the late 1920s by which Marxist-Leninist regimes in the Eastern Bloc and elsewhere attempted to establish an ordered socialist system in rural agriculture.[75] It required the forced consolidation of small scale peasant farms and larger holdings belonging to the landed classes for the purpose of creating larger modern "collective farms" owned, in theory, by the workers therein or the state.[75]

In addition to eradicating the perceived inefficiencies associated with small-scale farming on discontiguous land holdings, collectivization also purported to achieve the political goal of removing the rural basis for resistance to communist regimes.[75] A further justification given was the need to promote industrial development by facilitating the state's procurement of agricultural products and transferring "surplus labor" from rural to urban areas.[75] In short, agriculture was reorganised in order to proletarianise the peasantry and control production at prices determined by the state.[76]

The Eastern Bloc possesses substantial agricultural resources, especially in southern areas, such as Hungary's Great Plain, which offered good soils and a warm climate during the growing season.[76] Rural collectivization proceeded differently in non-Soviet Eastern Bloc countries than it did in the Soviet Union in the 1920s and 1930s.[77] Because of the need to conceal of the assumption of control and the realities of an initial lack of control, no Soviet dekulakization-style liquidation of rich peasants could be carried out in the non-Soviet Eastern Bloc countries.[77]

Nor could they risk mass starvation or agricultural sabotage (e.g., holodomor) with a rapid collectivization through massive state farms and agricultural producers' cooperatives (APCs).[77] Instead, collectivization proceeded more slowly and in stages from 1948 to 1960 in Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary, Czechoslovakia and East Germany, and from 1955 to 1964 in Albania.[77] Collectivization in the Baltic republics of the Lithuanian SSR, Estonian SSR and Latvian SSR took place between 1947 and 1952.[78]

Unlike Soviet collectivization, neither massive destruction of livestock nor errors causing distorted output or distribution occurred in the other Eastern Bloc countries.[77] More widespread use of transitional forms occurred, with differential compensation payments for peasants that contributed more land to APCs.[77] Because Czechoslovakia and East Germany were more industrialized than the Soviet Union, they were in a position to furnish most of the equipment and fertilizer inputs needed to ease the transition to collectivized agriculture.[54] Instead of liquidating large farmers or barring them from joining APCs as Stalin had done through dekulakization, those farmers were utilized in the non-Soviet Eastern Bloc collectivizations, sometimes even being named farm chairman or managers.[54] Massive industrialization eventually caused young men to move to urban centers, depressing agricultural productivity.[citation needed]

Collectivization often met with strong rural resistance, including peasants frequently destroying property rather than surrendering it to the collectives.[75] Strong peasant links with the land through private ownership were broken and many young people left for careers in industry.[76] In Poland and Yugoslavia, fierce resistance from peasants, many of whom had resisted the Axis, led to the abandonment of wholesale rural collectivization in the early 1950s.[54] In part because of the problems created by collectivization, agriculture was largely de-collectivized in Poland in 1957.[75]

The fact that Poland nevertheless managed to carry out large-scale centrally planned industrialization with no more difficulty than its collectivized Eastern Bloc neighbors further called into question the need for collectivization in such planned economies.[54] Only Poland's "western territories", those eastwardly adjacent to the Oder-Neisse line that were annexed from Germany, were substantially collectivized, largely in order to settle large numbers of Poles on good farmland which had been taken from German farmers.[54]

Stagnation

Developmental stagnation

Communist Europe effectively missed the information and electronics revolution of the 1970s and 1980s, though its development gap in this area compared to Western Europe was smaller than that of other developing countries.[79] By the 1980s, nearly all the economies of the region had stagnated, falling behind the technological advances of the West.[44] The systems, which required party-state planning at all levels, ended up collapsing under the weight of accumulated economic inefficiencies, with various attempts at reform merely contributing to the acceleration of crisis-generating tendencies.[80]

Western loans for technology transfer failed to boost productivity in state-owned enterprises built to hoard labor.[57] Western travelers across the German border to East Germany were often surprised by the effect on the environment of outmoded heating systems operating on cheap coal, industrial facilities without filters and smoke emanating from two-stroke car engines that provided a perceived distinct "GDR-smell." [81]

Transport in the Eastern Bloc was characterized by poor infrastructural maintenance.[82] The road network suffered from inadequate load capacity, poor surfacing and deficient roadside servicing.[82] While roads were resurfaced, few new roads were built and there were very few divided highway roads, urban ring roads or bypasses.[83] Private car ownership remained low by Western standards.[83]

Vehicle ownership increased in the 1970s and 1980s with the production of inexpensive cars in East Germany such as Trabants and the Wartburgs.[83] However, the wait list for the distribution of Trabants was ten years in 1987 and up to fifteen years for Soviet Lada and Czechoslovakian Škoda cars.[83] Soviet-built aircraft exhibited deficient technology, with high fuel consumption and heavy maintenance demands.[82] Telecommunications networks were overloaded.[82]

Adding to mobility constraints from the inadequate transport systems were bureaucratic mobility restrictions.[84] While outside of Albania, domestic travel eventually became largely regulation-free, stringent controls on the issue of passports, visas and foreign currency made foreign travel difficult inside the Eastern Bloc.[84] Countries were inured to isolation and initial post-war autarky, with each country effectively restricting bureaucrats to viewing issues from a domestic perspective shaped by that country's specific propaganda.[84]

Severe environmental problems arose through urban traffic congestion, which was aggravated by pollution generated by poorly maintained vehicles.[84] Large thermal power stations burning lignite and other items became notorious polluters, while some hydro-electric systems performed inefficiently because of dry seasons and silt accumulation in reservoirs.[85] Kraków, Poland was covered by smog 135 days per year, while Wrocław was covered by a fog of chrome gas.[specify][86]

Several villages were evacuated because of copper smelting at Głogów.[86] Further rural problems arose from piped water construction being given precedence over building sewerage systems, leaving many houses with only inbound piped water delivery and not enough sewage tank trucks to carry away sewage.[87] The resulting drinking water became so polluted in Hungary that over 700 villages had to be supplied by tanks, bottles and plastic bags.[87] Nuclear power projects were prone to long commissioning delays.[85]

The catastrophe at the Chernobyl nuclear plant in the Ukrainian SSR was caused by the use of an old flawed design,[88] some operators lacking an even basic understanding of the reactor's processes and authoritarian Soviet bureaucracy, valuing party loyalty over competence, that kept promoting incompetent personnel and choosing cheapness over safety.[89][90] The consequent release of fallout resulted in the evacuation and resettlement of over 336,000 people[91] leaving a massive desolate Zone of alienation containing extensive still-standing abandoned urban development.

Tourism from outside the Eastern Bloc was neglected, while tourism from other communist countries grew within the Eastern Bloc.[92] Tourism drew investment, relying upon tourism and recreation opportunities existing before World War II.[93] By 1945, most hotels were run-down, while many which escaped conversion to other uses by central planners were slated to meet domestic demands.[93] Authorities created state companies to arrange travel and accommodation.[93] In the 1970s, investments were made to attempt to attract western travelers, though momentum for this waned in the 1980s when no long-term plan arose to procure improvements in the tourist environment, such as an assurance of freedom of movement, free and efficient money exchange and the provision of higher quality products with which these tourists were familiar.[92]

Catering to western visitors required creating an environment of an entirely different standard than that used for the domestic populace, which required concentration of travel spots including the building of relatively high-quality infrastructure in travel complexes, which could not easily be replicated elsewhere.[92] In Albania, because of a desire to preserve ideological discipline and the fear of the presence of wealthier foreigners engaging in differing lifestyles, Albania segregated travelers.[94] Because of the worry of the subversive effect of the tourist industry, travel was restricted to 6,000 visitors per year.[95]

Lagging growth

Growth rates within the bloc experienced relative decline.[96] Meanwhile, West Germany, Austria, France and other Western European nations experienced increased economic growth in the Wirtschaftswunder ("economic miracle") Trente Glorieuses ("thirty glorious years") and the post-World War II boom. Overall, the inefficiency of systems without competition or market-clearing prices became costly and unsustainable, especially with the increasing complexity of world economics.[97]

From the end of the World War II to the mid-1970s, the economy of the Eastern Bloc steadily increased at the same rate as the economy in Western Europe, with the least none-reforming communist nations of the Eastern Bloc having a stronger economy then the reformist-communist states.[98] While most western European economies essentially began to approach the per capita Gross Domestic Product (GDP) levels of the United States during the late 1970s and early 1980s, the Eastern Bloc countries did not,[96] with per capita GDPs falling significantly below their comparable western European counterparts, for example (Eastern bloc countries are in red):[79]

| Per Capita GDP (1990 $) | 1938 | 1990 |

|---|---|---|

| Austria | $1,800 | $19,200 |

| Czechoslovak Socialist Republic | $1,800 | $3,100 |

| Finland | $1,800 | $16,100 |

| Italy | $1,300 | $16,800 |

| People's Republic of Hungary | $1,100 | $2,800 |

| People's Republic of Poland | $1,000 | $1,700 |

| Spain | $900 | $10,900 |

| Portugal | $800 | $4,900 |

| Greece | $800 | $6,000 |

| People's Republic of Romania | $700 | $1,600 |

| People's Republic of Bulgaria | $700 | $2,200 |

| Per Capita GDP 1989 Deutsche Marks[99] | 1989 |

|---|---|

| West Germany | 35,877 DM |

| East Germany | 15,318 DM |

| Per Capita GDP 1990 Dollars[100] | 1973 | 1990 |

|---|---|---|

| United States | $16,689 | $23,214 |

| USSR (all) | $6,058 | $6,871 |

| Russian SFSR | $6,577 | $7,762 |

| Ukrainian SSR | $4,933 | $5,995 |

| Byelorussian SSR | $5,234 | $7,153 |

| Estonian SSR | $8,656 | $10,733 |

| Latvian SSR | $7,780 | $9,841 |

| Lithuanian SSR | $7,589 | $8,591 |

| Moldavian SSR | $5,379 | $6,211 |

While, arguably the World Bank estimates of GDP used for 1990 figures above underestimate Eastern Bloc GDP because of undervalued local currencies, per capita incomes are undoubtedly lower than in their counterparts.[79] East Germany was the most advanced industrial nation of the Eastern bloc.[60] Until the 1961 Berlin Wall erection, East Germany was considered a weak state, hemorrhaging skilled labor to the West such that it was referred to as "the disappearing satellite."[101] Only after the wall sealed in skilled labor was East Germany able to ascend to the top economic spot in the Eastern Bloc.[101] Thereafter, its citizens enjoyed a higher quality of life and less good supply shortages than those in the Soviet Union, Poland or Romania.[60]

While official statistics painted a relatively rosy picture, the East German economy had eroded because of increased central planning, economic autarky, the use of coal over oil, investment concentration in a few selected technology-intensive areas and labor market regulation.[102] As a result, a large productivity gap of nearly 50% per worker existed between East and West Germany.[102][103] However, that gap does not measure the quality of design of goods or service such that the actual per capita rate may be as low as 14 to 20 per cent.[103] Average gross monthly wages in East Germany were around 30% of those in West Germany, though after accounting for taxation, the figures approached 60%.[104]

Moreover, the purchasing power of wages grossly differed, with only about half of East German households owning either a car or a color television set as late as 1990, both of which had been standard possessions in West German households.[104] The Ostmark was only valid for transactions inside East Germany, could not be legally exported or imported[104] and could not be used in the East German Intershops which sold premium goods.[60] In 1989, 11% of the East German labor force remained in agriculture, 47% was in the secondary sector and only 42% in services.[103]

Using Switzerland's economy as a European base for comparison across time, where the GDP for Switzerland is 100 for all periods (Eastern Bloc countries are in red), yields for five Eastern Bloc countries:[105][106]

| Per Capita GDP (index) | 1938 | 1948 | 1990 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Switzerland | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Austria | 58.5 | 35.6 | 79.2 |

| Czechoslovak Socialist Republic | 44.5 | 44.2 | 38.5 |

| West Germany | 93.5 | 36.3 | 87.1 |

| People's Republic of Hungary | 37.5 | 22.2 | 28.9 |

| Italy | 45.8 | 23.8 | 76.3 |

| People's Republic of Poland | 30.9 | 32.0 | 21.1 |

| People's Republic of Romania | 28.5 | -- | 15.1 |

| Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia | 28.2 | -- | 25.3 |

A further comparison beginning several years after occupation, in 1950, using different GDP figures shows per capita GDP:[100]

| Per Capita GDP (1990 $) | 1950 | 1973 | 1990 | highest and year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | $3,706 | $11,235 | $16,895 | na |

| Italy | $3,502 | $10,634 | $16,320 | na |

| Czechoslovak Socialist Republic | $3,501 | $7,041 | $8,513 | $8,768 (1989) |

| Soviet Union | $2,841 | $6,059 | $6,894 | $7,112 (1989) |

| People's Republic of Hungary | $2,480 | $5,596 | $6,459 | $7,031 (1989) |

| Spain | $2,189 | $7,661 | $12,055 | na |

| Portugal | $2,086 | $7,063 | $10,826 | na |

| Greece | $1,915 | $7,655 | $10,015 | na |

| People's Republic of Bulgaria | $1,651 | $5,284 | $5,597 | $6,430 (1984) |

| Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia | $1,551 | $4,361 | $5,646 | $6,522 (1986) |

| People's Republic of Romania | $1,182 | $3,477 | $3,511 | $4,215 (1986) |

Once installed, the economic system was difficult to change given the importance of politically reliable management and the prestige value placed on large enterprises.[57] Performance declined during the 1970s and 1980s due to inefficiency when industrial input costs, such as energy prices, increased.[57] Though growth lagged behind the west, it did occur.[44] Consumer goods started to become more available by the 1960s.[44]

Before the Eastern Bloc's dissolution, some major sectors of industry were operating at such a loss that they exported products to the West at prices below the real value of the raw materials.[107] Hungarian steel costs doubled those of western Europe.[107] In 1985, a quarter of Hungary's state budget was spent on supporting inefficient enterprises.[107] Tight planning in Bulgaria industry meant continuing shortages in other parts of its economy.[107]

Population

The communist economical and political system produced further consequences such as, for example, in Baltic states, where the population was approximately half of what it should have been compared with similar countries such as Denmark, Finland and Norway over the years 1939–1990. Poor housing was one factor leading to severely declining birth rates throughout the Eastern Bloc.[108] However, birth rates were still higher than in Western European countries. A reliance upon abortion, in part because periodic shortages of birth control pills and intrauterine devices made these systems unreliable,[66] also depressed the birth rate and forced a shift to pro-natalist policies by the late 1960s, including severe checks on abortion and propagandist exhortations like the 'heroine mother' distinction bestowed on those Romanian women who bore ten or more children.[109]

In October 1966, artificial birth control was proscribed in Romania and regular pregnancy tests were mandated for women of child-bearing age, with severe penalties for anyone who was found to have terminated a pregnancy.[110] Despite such restrictions, birth rates continued to lag, in part, because of unskilled induced abortions.[109] Population in Eastern Bloc countries was as follows:[111][112]

|

Housing

A housing shortage existed throughout the Eastern Bloc, especially after a severe cutback in state resources available for housing starting in 1975.[113] Cities became filled with large system-built apartment blocks[55] Western visitors from places like West Germany expressed surprise at the perceived shoddiness of new, box-like concrete structures across the border in East Germany, along with a relative greyness of the physical environment and the often joyless appearance of people on the street or in stores.[81] Housing construction policy suffered from considerable organizational problems.[114] Moreover, completed houses possessed noticeably poor quality finishes.[114]

Policy development

During the years 1957-65 housing policy underwent several institutional changes with industrialization and urbanization had not been matched by an increase in housing after World War II.[115] Housing shortages in the Soviet Union were worse than in the rest of the Eastern Bloc due to a larger migration to the towns and more wartime devastation, and were worsened by Stalin's pre-war refusals to invest properly in housing.[115] Because such investment was generally not enough to sustain the existing population, apartments had to be subdivided into increasingly smaller units, resulting in several families sharing an apartment previously meant for one family.[115]

The prewar norm became one Soviet family per room, with the toilets and kitchen shared.[115] The amount of living space in urban areas fell from 5.7 square meters per person in 1926 to 4.5 square meters in 1940.[115] In the rest of the Eastern Bloc during this time period, the average number of people per room was 1.8 in Bulgaria (1956), 2.0 in Czechoslovakia (1961), 1.5 in Hungary (1963), 1.7 in Poland (1960), 1.4 in Romania (1966), 2.4 in Yugoslavia (1961), and 0.9 in 1961 in East Germany.[115]

After Stalin's death in 1953, forms of an economic "New Course" brought a revival of private house construction.[115] Private construction peaked in 1957–1960 in many Eastern Bloc countries and then declined simultaneously along with a steep increase in state and co-operative housing.[115] By 1960, the rate of house-building per head had picked up in all countries in the Eastern Bloc.[115] Between 1950 and 1975, worsening shortages were generally caused by a fall in the proportion of all investment made housing.[116] However, during that period the total number of dwellings increased.[117]

During the last fifteen years of this period (1960 to 1975), an emphasis was made for a supply side solution, which assumed that industrialized building methods and high rise housing would be cheaper and quicker than traditional brick-built, low-rise housing.[117] Such methods required manufacturing organizations to produce the prefabricated components and organizations to assemble them on site, both of which planners assumed would employ large numbers of unskilled workers-with powerful political contacts.[117] The lack of participation of eventual customers, the residents, constituted one factor in escalating construction costs and poor quality work.[118] This led to higher demolition rates and higher costs to repair poorly constructed dwellings.[118] In addition, because of poor quality work, a black market arose for building services and materials that could not be procured from state monopolies.[118]

In most countries, completions (new dwellings constructed) rose to a high point between 1975 and 1980 and then fell, as a result presumably of worsening international economic conditions.[119] This occurred in Bulgaria, Hungary, East Germany, Poland, Romania (with an earlier peak in 1960 also), Czechoslovakia, and Yugoslavia, while the Soviet Union peaked in 1960 and 1970.[119] While between 1975 and 1986, the proportion of investment devoted to housing actually rose in most of the Eastern Bloc, general economic conditions resulted in total investment amounts falling or becoming stagnant.[116]

The employment of socialist ideology in housing policy declined in the 1980s, which accompanied a shift in authorities looking at the need of residents to an examination of potential residents' ability to pay.[116] Yugoslavia was unique in that it continuously mixed private and state sources of housing finance, stressed self-managed building co-operatives along with central government controls.[116]

Shortages

The initial year that shortages were effectively measured and shortages in 1986 were as follows:[120]

|

These are official housing figures and may be low. For example, in the Soviet Union, the figure of 26,662,400 in 1986 almost certainly underestimates shortages for the reason that it does not count shortages from large Soviet rural-urban migration; another calculation estimates shortages to be 59,917,900.[121] By the late 1980s, Poland had an average 20 year wait time for housing, while Warsaw had between a 26 and 50 year wait time.[107][122] In the Soviet Union, widespread illegal subletting occurred at exorbitant rates.[123] Toward the end of the Eastern Bloc allegations of misallocations and illegal distribution of housing were raised in Soviet CPSU Central Committee meetings.[123]

In Poland, housing problems were caused by slow rates of construction, poor home quality (which was even more pronounced in villages), and a large black market.[114] In Romania, social engineering policy and concern about the use of agricultural land forced high densities and high-rise housing designs.[124] In Bulgaria, a prior emphasis on monolithic high-rise housing lessened somewhat in the 1970s and 1980s.[124] In the Soviet Union, housing was perhaps the primary social problem.[124] While Soviet housing construction rates were high, quality was poor and demolition rates were high, in part because of an inefficient building industry and lack of both quality and quantity of construction materials.[124]

East German housing suffered from a lack of quality and a lack of skilled labor, with a shortage of materials, plot and permits.[52] In staunchly Stalinist Albania, housing blocks (panelka) were spartan, with six story walk-ups being the most frequent design.[52] Housing was allocated by workplace trade unions and built by voluntary labor organized into brigades within the workplace.[52] Yugoslavia suffered from fast urbanization, uncoordinated development and poor organization resulting from a lack of hierarchical structure and clear accountability, low building productivity, the monopoly position of building enterprises, and irrational credit policies.[52]

Housing quality

The near-total emphasis on large apartment blocks was a common feature of Eastern Bloc cities in the 1970s and 1980s.[125] East German authorities viewed large cost advantages in the construction of Plattenbau apartment blocks such that the building of such architecture on the edge of large cities continued until the dissolution of the Eastern Bloc.[125] These buildings, such as the Paneláks of Czechoslovakia and Panelház of Hungary, contained cramped concrete apartments that broadly lined Eastern Bloc streets, leaving the visitor with a "cold and grey" impression.[125] Wishing to reinforce the role of the state in the 1980s, Nicolae Ceaușescu redeveloped part of Bucharest, Romania with Systematization of constructing such buildings (Blocs) after the demolition of extensive private housing.[125]

Even by the late 1980s, sanitary conditions in most Eastern bloc countries were generally far from adequate.[126] For all countries for which data existed, 60% of dwellings had a density of greater than one person per room between 1966 and 1975.[126] The average in western countries for which data was available approximated 0.5 persons per room.[126] Problems were aggravated by poor quality finishes on new dwellings often causing occupants to undergo a certain amount of finishing work and additional repairs.[126] Housing quality figures for the Eastern Bloc are as follows:[127]

|

|

The worsening shortages of the 1970s and 1980s occurred during an increase in the quantity of dwelling stock relative to population from 1970 to 1986.[128] Even for new dwellings, average dwelling size was only 61.3m2 in the Eastern Bloc compared with 113.5m2 in ten western countries for which comparable data was available.[128] Space standards varied considerably, with the average new dwelling in the Soviet Union in 1986 being only 68 per cent the size of its equivalent in Hungary.[128] Apart from exceptional cases, such as East Germany in 1980–1986 and Bulgaria in 1970–1980, space standards in newly-built dwellings rose before the dissolution of the Eastern Bloc.[128] The figures are as follows:[129]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Poor housing was one of four factors leading to severely declining birth rates throughout the Eastern Bloc.[108] Homelessness was the most obvious effect of the housing shortage, though it was hard to define and measure in the Eastern Bloc.[122]

See also

Notes

- ^ For an overview, see Myant, Martin (2010). Transition Economies: Political Economy in Russia, Eastern Europe, and Central Asia. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 1–46. ISBN 978-0-470-59619-7.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Wettig 2008, p. 69

- ^ Roberts 2006, p. 43

- ^ a b c Wettig 2008, p. 21

- ^ a b c Senn, Alfred Erich, Lithuania 1940 : revolution from above, Amsterdam, New York, Rodopi, 2007 ISBN 978-90-420-2225-6

- ^ Kennedy-Pipe, Caroline, Stalin's Cold War, New York : Manchester University Press, 1995, ISBN 978-0-7190-4201-0

- ^ Roberts 2006, p. 55

- ^ Shirer 1990, p. 794

- ^ a b c Graubard 1991, p. 150

- ^ Granville, Johanna, The First Domino: International Decision Making during the Hungarian Crisis of 1956, Texas A&M University Press, 2004. ISBN 978-1-58544-298-0

- ^ Grenville 2005, pp. 370–71

- ^ Cook 2001, p. 17

- ^ Wettig 2008, pp. 96–100

- ^ Crampton 1997, pp. 216–7

- ^ Eastern bloc, The American Heritage New Dictionary of Cultural Literacy, Third Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2005.

- ^ Wettig 2008, p. 156

- ^ Historia Polski 1918-1945: Tom 1 Czesław Brzoza, Andrzej Sowa, page 697, Wydawnictwo Literackie, 2006

- ^ Poles Vote to Seek War Reparations, Deutsche Welle, 11 September 2004

- ^ Historia Polski, 1939-1947 Józef Ryszard Szaflik, p. 171; Wydawnictwa Szkolne i Pedagogiczne, 1987

- ^ Historia Polski 1918-1945: Tom 1 Czesław Brzoza, Andrzej Sowa, p. 697, Wydawnictwo Literackie, 2006

- ^ The European economy 1914-2000 Derek Howard Aldcroft,Steven Morewood,page 241, Routledge 2001

- ^ a b Hardt & Kaufman 1995, p. 11

- ^ Hardt & Kaufman 1995, p. 12

- ^ a b Roht-Arriaza 1995, p. 83

- ^ a b Pollack & Wielgohs 2004, p. xiv

- ^ O'Neil, Patrick (1997). Post-communism and the Media in Eastern Europe. Routledge. p. 15–25. ISBN 978-0-7146-4765-4.

- ^ Böcker 1998, pp. 207–9

- ^ Dowty 1989, p. 114

- ^ Laqueur 1994, p. 23

- ^ a b Laqueur 1994, p. 22

- ^ Turnock 1997, p. 23

- ^ a b c d Turnock 2006, p. 267

- ^ Turnock 2006, p. 270

- ^ a b Wettig 2008, p. 36

- ^ a b c Wettig 2008, p. 37

- ^ Wettig 2008, p. 38

- ^ Pearson 1998, pp. 29–30

- ^ a b Bideleux & Jeffries 2007, p. 461

- ^ a b Black et al. 2000, p. 86

- ^ Crampton 1997, p. 211

- ^ Black et al. 2000, p. 87

- ^ a b c d Black et al. 2000, p. 88

- ^ Black et al. 2000, p. 82

- ^ a b c d e f g Frucht 2003, p. 382

- ^ Turnock 1997, p. 26

- ^ Turnock 1997, p. 27

- ^ a b Crampton 1997, pp. 312–3

- ^ a b c d Crampton 1997, p. 250

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Crampton 1997, p. 251

- ^ a b c Crampton 1997, p. 252

- ^ a b c d e f g h Frucht 2003, p. 442

- ^ a b c d e f Sillince 1990, p. 4

- ^ Hardt & Kaufman 1995, p. 15

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Bideleux & Jeffries 2007, p. 474

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Bideleux & Jeffries 2007, p. 475

- ^ Turnock 1997, p. 29

- ^ a b c d e f g Turnock 1997, p. 24

- ^ Dale 2005, p. 85

- ^ Zwass 1984, p. 12

- ^ a b c d Zwass 1984, p. 34

- ^ Adelman, Deborah, The "children of Perestroika" come of age: young people of Moscow talk about life in the new Russia, M.E. Sharpe, 1994, ISBN 978-1-56324-287-8, page 162

- ^ Nagengast, Carole, Reluctant Socialists, Rural Entrepreneurs: Class, Culture, and the Polish State, Westview Press, 1991, ISBN 978-0-8133-8053-7,page 85

- ^ a b c Bugajski & Pollack 1989, p. 189

- ^ Graubard, Stephen R., Eastern Europe, Central Europe, Europe, Westview Press, 1991, ISBN 978-0-8133-1189-0, page 130

- ^ Dale 2005, p. 86

- ^ a b Frucht 2003, p. 851

- ^ Frucht 2003, p. 204

- ^ a b Bugajski & Pollack 1989, p. 188

- ^ a b Bugajski & Pollack 1989, p. 190

- ^ a b c d e Crampton 1997, p. 272

- ^ a b c Crampton 1997, p. 271

- ^ Deletant 1995, p. xvii

- ^ a b c Crampton 1997, p. 278

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Crampton 1997, p. 279

- ^ a b c d e f Frucht 2003, p. 144

- ^ a b c Turnock 1997, p. 34

- ^ a b c d e f Bideleux & Jeffries 2007, p. 473

- ^ O'Connor 2003, p. xx-xxi

- ^ a b c Hardt & Kaufman 1995, p. 17

- ^ Hardt & Kaufman 1995, p. 10

- ^ a b Philipsen 1993, p. 9

- ^ a b c d Turnock 1997, p. 42

- ^ a b c d Turnock 1997, p. 41

- ^ a b c d Turnock 1997, p. 43

- ^ a b Turnock 1997, p. 39

- ^ a b Turnock 1997, p. 63

- ^ a b Turnock 1997, p. 64

- ^ NEI Source Book: Fourth Edition (NEISB_3.3.A1)

- ^ Medvedev, Grigori (1989). The Truth About Chernobyl. VAAP. First American edition published by Basic Books in 1991. ISBN 978-2-226-04031-2.

- ^ Medvedev, Zhores A. (1990). The Legacy of Chernobyl. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-30814-3.

- ^ "Geographical location and extent of radioactive contamination". Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation. (quoting the "Committee on the Problems of the Consequences of the Catastrophe at the Chernobyl NPP: 15 Years after Chernobyl Disaster", Minsk, 2001, p. 5/6 ff., and the "Chernobyl Interinform Agency, Kiev und", and "Chernobyl Committee: MailTable of official data on the reactor accident")

- ^ a b c Turnock 1997, p. 45

- ^ a b c Turnock 1997, p. 44

- ^ Turnock 2006, p. 350

- ^ Turnock 1997, p. 48

- ^ a b Hardt & Kaufman 1995, p. 16

- ^ Hardt & Kaufman 1995, p. 1

- ^ Teichova, & Matis 2003, p. 152

- ^ Teichova & Matis 2003, p. 724

- ^ a b Madison 2006, p. 185

- ^ a b Graubard 1991, p. 8

- ^ a b Lipschitz & McDonald 1990, p. 52

- ^ a b c Teichova & Matis 2003, p. 72

- ^ a b c Lipschitz & McDonald 1990, p. 53

- ^ Butschek 1994, pp. 29–30

- ^ note the list shows statistics before the erection of the bloc, at the beginning and its economic collapse

- ^ a b c d e Turnock 1997, p. 25

- ^ a b Sillince 1990, p. 35

- ^ a b Turnock 1997, p. 17

- ^ Crampton 1997, p. 355

- ^ Turnock 1997, p. 15

- ^ Andreev, E.M., et al., Naselenie Sovetskogo Soiuza, 1922–1991. Moscow, Nauka, 1993. ISBN 978-5-02-013479-9

- ^ Sillince 1990, p. 1

- ^ a b c Sillince 1990, p. 2

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Sillince 1990, pp. 36–7

- ^ a b c d Sillince 1990, p. 748

- ^ a b c Sillince 1990, p. 49

- ^ a b c Sillince 1990, p. 50

- ^ a b Sillince 1990, p. 7

- ^ Sillince 1990, pp. 11–12

- ^ Sillince 1990, p. 17

- ^ a b Sillince 1990, p. 27

- ^ a b Sillince 1990, p. 33

- ^ a b c d Sillince 1990, p. 3

- ^ a b c d Turnock 1997, p. 54

- ^ a b c d Sillince 1990, p. 18

- ^ Sillince 1990, pp. 19–20

- ^ a b c d Sillince 1990, p. 14

- ^ Sillince 1990, p. 15

References

- Beschloss, Michael R (2003), The Conquerors: Roosevelt, Truman and the Destruction of Hitler's Germany, 1941–1945, Simon and Schuster, ISBN 978-0-7432-6085-5

- Butschek, Felix (1994), "External Shocks And Long-Term Patterns of Economic Growth in Central and Eastern Europe", in Good, David F. (ed.), Economic Transformations in East and Central Europe: Legacies from the Past and Policies for the Future, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-11266-6

- Bideleux, Robert; Jeffries, Ian (2007), A History of Eastern Europe: Crisis and Change, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-36626-7

- Black, Cyril E.; English, Robert D.; Helmreich, Jonathan E.; McAdams, James A. (2000), Rebirth: A Political History of Europe since World War II, Westview Press, ISBN 978-0-8133-3664-0

- Böcker, Anita (1998), Regulation of Migration: International Experiences, Het Spinhuis, ISBN 978-90-5589-095-8

- Bugajski, Janusz; Pollack, Maxine (1989), East European Fault Lines: Dissent, Opposition, and Social Activism, Westview Press, ISBN 978-0-8133-7714-8

- Cook, Bernard A. (2001), Europe Since 1945: An Encyclopedia, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 978-0-8153-4057-7

- Crampton, R. J. (1997), Eastern Europe in the twentieth century and after, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-16422-1

- Dale, Gareth (2005), Popular Protest in East Germany, 1945–1989: Judgments on the Street, Routledge, ISBN 071465408

{{citation}}: Check|isbn=value: length (help) - Deletant, Dennis (1995), Ceauşescu and the Securitate: coercion and dissent in Romania, 1965–1989, M.E. Sharpe, ISBN 978-1-56324-633-3

- Dowty, Alan (1989), Closed Borders: The Contemporary Assault on Freedom of Movement, Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-04498-0

- Frucht, Richard C. (2003), Encyclopedia of Eastern Europe: From the Congress of Vienna to the Fall of Communism, Taylor & Francis Group, ISBN 978-0-203-80109-3

- Graubard, Stephen R. (1991), Eastern Europe, Central Europe, Europe, Westview Press, ISBN 978-0-8133-1189-0

- Grenville, John Ashley Soames (2005), A History of the World from the 20th to the 21st Century, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-28954-2

- Grenville, John Ashley Soames; Wasserstein, Bernard (2001), The Major International Treaties of the Twentieth Century: A History and Guide with Texts, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 978-0-415-23798-7

- Hardt, John Pearce; Kaufman, Richard F. (1995), East-Central European Economies in Transition, M.E. Sharpe, ISBN 978-1-56324-612-8

- Laqueur, Walter (1994), The dream that failed: reflections on the Soviet Union, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-510282-6

- Lipschitz, Leslie; McDonald, Donogh (1990), German unification: economic issues, International Monetary Fund, ISBN 978-1-55775-200-0

- Maddison, Angus (2006), The world economy, OECD Publishing, ISBN 978-92-64-02261-4

- Myant, Martin; Drahokoupil, Jan (2010), Transition Economies: Political Economy in Russia, Eastern Europe, and Central Asia, Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 978-0-470-59619-7

- O'Connor, Kevin (2003), The history of the Baltic States, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0-313-32355-3

- O'Neil, Patrick (1997), Post-communism and the Media in Eastern Europe, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-7146-4765-4

- Pearson, Raymond (1998), The Rise and Fall of the Soviet Empire, Macmillan, ISBN 978-0-312-17407-1

- Philipsen, Dirk (1993), We were the people: voices from East Germany's revolutionary autumn of 1989, Duke University Press, ISBN 978-0-8223-1294-9

- Pollack, Detlef; Wielgohs, Jan (2004), Dissent and Opposition in Communist Eastern Europe: Origins of Civil Society and Democratic Transition, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., ISBN 978-0-7546-3790-5

- Roberts, Geoffrey (2006), Stalin's Wars: From World War to Cold War, 1939–1953, Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-11204-7

- Roht-Arriaza, Naomi (1995), Impunity and human rights in international law and practice, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-508136-7

- Shirer, William L. (1990), The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich: A History of Nazi Germany, Simon and Schuster, ISBN 978-0-671-72868-7

- Sillince, John (1990), Housing policies in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-02134-0

- Teichova, Alice; Matis, Herbert (2003), Nation, State, and the Economy in History, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-79278-3

- Turnock, David (1997), The East European economy in context: communism and transition, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-08626-4

- Turnock, David (2006), The economy of East Central Europe 1815-1989: stages of transformation in a peripheral region, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-18053-5

- Wettig, Gerhard (2008), Stalin and the Cold War in Europe, Rowman & Littlefield, ISBN 978-0-7425-5542-6

- Zwass, Adam (1984), The Economies of Eastern Europe in a Time of Change, M.E. Sharpe, ISBN 978-0-87332-245-4