Homo: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Geoffspear (talk | contribs) Undid revision 507435851 by 86.29.43.86 (talk) |

||

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

The advent of ''Homo'' was thought to coincide with the first evidence of [[stone tool]]s (the [[Oldowan]] industry), and thus by definition with the beginning of the [[Lower Palaeolithic]]; however, recent evidence from Ethiopia now places the earliest evidence of stone tool usage at before 3.39 million years ago.<ref>McPherron, S. P., Z. Alemseged, C. W. Marean, J. G. Wynn, D. Reed, D. Geraads, R. Bobe, and H. A. Bearat. 2010. Evidence for stone-tool-assisted consumption of animal tissues before 3.39 million years ago at Dikika, Ethiopia. ''Nature'' 466:857-860.</ref> The emergence of ''Homo'' coincides roughly with the onset of [[Quaternary glaciation]], the beginning of the current [[ice age]]. |

The advent of ''Homo'' was thought to coincide with the first evidence of [[stone tool]]s (the [[Oldowan]] industry), and thus by definition with the beginning of the [[Lower Palaeolithic]]; however, recent evidence from Ethiopia now places the earliest evidence of stone tool usage at before 3.39 million years ago.<ref>McPherron, S. P., Z. Alemseged, C. W. Marean, J. G. Wynn, D. Reed, D. Geraads, R. Bobe, and H. A. Bearat. 2010. Evidence for stone-tool-assisted consumption of animal tissues before 3.39 million years ago at Dikika, Ethiopia. ''Nature'' 466:857-860.</ref> The emergence of ''Homo'' coincides roughly with the onset of [[Quaternary glaciation]], the beginning of the current [[ice age]]. |

||

All species of the genus except ''[[Human|Homo sapiens]]'' (modern humans) are extinct. ''[[Homo neanderthalensis]]'', traditionally considered the last surviving relative, died out about 24,000 years ago, though a recent discovery suggests another species, ''[[Homo floresiensis]]'', discovered in |

All species of the genus except ''[[Human|Homo sapiens]]'' (modern humans) are extinct. ''[[Homo neanderthalensis]]'', traditionally considered the last surviving relative, died out about 24,000 years ago, though a recent discovery suggests another species, ''[[Homo floresiensis]]'', discovered in 2003, may have lived as recently as 12,000 years ago. The other extant [[Homininae]]—the [[chimpanzee]]s and [[gorilla]]s—have a limited geographic range. In contrast, the evolution of humans is a history of migrations and admixture. According to [[genetics|genetic studies]], modern humans bred with "at least two groups" of [[ancient humans]]: [[Neanderthals]] and [[Denisovans]].<ref name="NYT-01302012">{{cite news |last=Mitchell |first=Alanna |title=DNA Turning Human Story Into a Tell-All |url=http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/31/science/gains-in-dna-are-speeding-research-into-human-origins.html |date=January 30, 2012 |publisher=[[NYTimes]] |accessdate=January 31, 2012 }}</ref> Humans repeatedly left Africa to populate Eurasia and finally the Americas, Oceania, and the rest of the world. |

||

According to scientists in June 2012, early humans, such as [[Australopithecus sediba]], may have lived in [[savanna]]s but ate [[fruits]] and other foods from the [[forest]] - behavior similar to modern-day savanna [[chimpanzees]].<ref name="Nature-20120627">{{cite journal |last1=Henry |first1=Amanda G. |last2=Ungar |first2=Peter S. |last3=Passey |first3=Benjamin H. |last4=Sponheimer |first4=Matt |last5=Rossouw |first5=Lloyd |last6=Bamford |first6=Marion |last7=Sandberg |first7=Paul |last8=de Ruiter |first8=Darryl J. |last9=Berger |first9=Lee |title=The diet of Australopithecus sediba |url=http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/vaop/ncurrent/full/nature11185.html |date=June 27, 2012 |journal=[[Nature (journal)]] |doi=10.1038/nature11185 |accessdate=June 28, 2012 }}</ref><ref name="MSNBC-20120627">{{cite web |last=Boyle |first=Alan |title=This pre-human ate like a chimp |url=http://cosmiclog.msnbc.msn.com/_news/2012/06/27/12430341-this-pre-human-ate-like-a-chimp |date=June 27, 2012 |publisher=[[MSNBC]] |accessdate=June 28., 2012 }}</ref><ref name="NYT-20120628">{{cite news |last=Wilford |first=John Noble |title=Some Prehumans Feasted on Bark Instead of Grasses |url=http://www.nytimes.com/2012/06/28/science/australopithecus-sediba-preferred-forest-foods-fossil-teeth-suggest.html |date=June 28, 2012 |newspaper=[[New York Times]] |accessdate=June 28, 2012 }}</ref> |

According to scientists in June 2012, early humans, such as [[Australopithecus sediba]], may have lived in [[savanna]]s but ate [[fruits]] and other foods from the [[forest]] - behavior similar to modern-day savanna [[chimpanzees]].<ref name="Nature-20120627">{{cite journal |last1=Henry |first1=Amanda G. |last2=Ungar |first2=Peter S. |last3=Passey |first3=Benjamin H. |last4=Sponheimer |first4=Matt |last5=Rossouw |first5=Lloyd |last6=Bamford |first6=Marion |last7=Sandberg |first7=Paul |last8=de Ruiter |first8=Darryl J. |last9=Berger |first9=Lee |title=The diet of Australopithecus sediba |url=http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/vaop/ncurrent/full/nature11185.html |date=June 27, 2012 |journal=[[Nature (journal)]] |doi=10.1038/nature11185 |accessdate=June 28, 2012 }}</ref><ref name="MSNBC-20120627">{{cite web |last=Boyle |first=Alan |title=This pre-human ate like a chimp |url=http://cosmiclog.msnbc.msn.com/_news/2012/06/27/12430341-this-pre-human-ate-like-a-chimp |date=June 27, 2012 |publisher=[[MSNBC]] |accessdate=June 28., 2012 }}</ref><ref name="NYT-20120628">{{cite news |last=Wilford |first=John Noble |title=Some Prehumans Feasted on Bark Instead of Grasses |url=http://www.nytimes.com/2012/06/28/science/australopithecus-sediba-preferred-forest-foods-fossil-teeth-suggest.html |date=June 28, 2012 |newspaper=[[New York Times]] |accessdate=June 28, 2012 }}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 21:30, 14 August 2012

| Homo Temporal range: Pliocene–present

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Homo habilis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Hominidae |

| Subfamily: | Homininae |

| Tribe: | Hominini |

| Subtribe: | Hominina |

| Genus: | Homo Linnaeus, 1758 |

| Type species | |

| Homo sapiens Linnaeus, 1758

| |

| Species | |

Homo is the genus that includes modern humans and species closely related to them. The genus is estimated to be about 2.3 to 2.4 million years old,[1][2] having evolved from australopithecine ancestors with the appearance of Homo habilis. Specifically, H. habilis is assumed to be the direct descendant of Australopithecus garhi, which lived about 2.5 million years ago. However, in May 2010 H. gautengensis was discovered, a species believed to be even older than H. habilis.[3]

The most salient physiological development between the two species is the increase in cranial capacity, from about 450 cc (27 cu in) in A. garhi to 600 cc (37 cu in) in H. habilis. Within the Homo genus, cranial capacity again doubled from H. habilis through Homo ergaster or H. erectus to Homo heidelbergensis by 0.6 million years ago. The cranial capacity of H. heidelbergensis overlaps with the range found in modern humans.

The advent of Homo was thought to coincide with the first evidence of stone tools (the Oldowan industry), and thus by definition with the beginning of the Lower Palaeolithic; however, recent evidence from Ethiopia now places the earliest evidence of stone tool usage at before 3.39 million years ago.[4] The emergence of Homo coincides roughly with the onset of Quaternary glaciation, the beginning of the current ice age.

All species of the genus except Homo sapiens (modern humans) are extinct. Homo neanderthalensis, traditionally considered the last surviving relative, died out about 24,000 years ago, though a recent discovery suggests another species, Homo floresiensis, discovered in 2003, may have lived as recently as 12,000 years ago. The other extant Homininae—the chimpanzees and gorillas—have a limited geographic range. In contrast, the evolution of humans is a history of migrations and admixture. According to genetic studies, modern humans bred with "at least two groups" of ancient humans: Neanderthals and Denisovans.[5] Humans repeatedly left Africa to populate Eurasia and finally the Americas, Oceania, and the rest of the world.

According to scientists in June 2012, early humans, such as Australopithecus sediba, may have lived in savannas but ate fruits and other foods from the forest - behavior similar to modern-day savanna chimpanzees.[6][7][8]

Naming

In biological sciences, particularly anthropology and palaeontology, the common name for all members of the genus Homo is "human".

The word homo is Latin, in the original sense of "human being", or "man" (in the gender-neutral sense). The word "human" itself is from Latin humanus, an adjective cognate to homo, both thought to derive from a Proto-Indo-European word for "earth" reconstructed as *dhǵhem-.[9]

The binomial name Homo sapiens is due to Carl Linnaeus[10] (1758).

Names for other species were coined beginning in the second half of the 19th century (H. neanderthalensis 1864, H. erectus 1892).

Species

Species status of Homo rudolfensis, H. ergaster, H. georgicus, H. antecessor, H. cepranensis, H. rhodesiensis and H. floresiensis remains under debate. H. heidelbergensis and H. neanderthalensis are closely related to each other and have been considered to be subspecies of H. sapiens. Recently, nuclear DNA from a Neanderthal specimen from Vindija Cave has been sequenced, as well, using two different methods that yield similar results regarding Neanderthal and H. sapiens lineages, with both analyses suggesting a date for the split between 460,000 and 700,000 years ago, though a population split of around 370,000 years is inferred. The nuclear DNA results indicate about 30% of derived alleles in H. sapiens are also in the Neanderthal lineage. This high frequency may suggest some gene flow between ancestral humans and Neanderthal populations.[11]

| Lineages | Temporal range (kya) |

Habitat | Adult height | Adult mass | Cranial capacity (cm3) |

Fossil record | Discovery | Publication of name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H. habilis membership in Homo uncertain |

2,100–1,500[a][b] | Tanzania | 110–140 cm (3 ft 7 in – 4 ft 7 in) | 33–55 kg (73–121 lb) | 510–660 | Many | 1960 | 1964 |

| H. rudolfensis membership in Homo uncertain |

1,900 | Kenya | 700 | 2 sites | 1972 | 1986 | ||

| H. gautengensis also classified as H. habilis |

1,900–600 | South Africa | 100 cm (3 ft 3 in) | 3 individuals[14][c] | 2010 | 2010 | ||

| H. erectus | 1,900–140[15][d][16][e] | Africa, Eurasia | 180 cm (5 ft 11 in) | 60 kg (130 lb) | 850 (early) – 1,100 (late) | Many[f][g] | 1891 | 1892 |

| H. ergaster African H. erectus |

1,800–1,300[18] | East and Southern Africa | 700–850 | Many | 1949 | 1975 | ||

| H. antecessor | 1,200–800 | Western Europe | 175 cm (5 ft 9 in) | 90 kg (200 lb) | 1,000 | 2 sites | 1994 | 1997 |

| H. heidelbergensis early H. neanderthalensis |

600–300[h] | Europe, Africa | 180 cm (5 ft 11 in) | 90 kg (200 lb) | 1,100–1,400 | Many | 1907 | 1908 |

| H. cepranensis a single fossil, possibly H. heidelbergensis |

c. 450[19] | Italy | 1,000 | 1 skull cap | 1994 | 2003 | ||

| H. longi | 309–138[20] | Northeast China | 1,420[21] | 1 individual | 1933 | 2021 | ||

| H. rhodesiensis early H. sapiens |

c. 300 | Zambia | 1,300 | Single or very few | 1921 | 1921 | ||

| H. naledi | c. 300[22] | South Africa | 150 cm (4 ft 11 in) | 45 kg (99 lb) | 450 | 15 individuals | 2013 | 2015 |

| H. sapiens (anatomically modern humans) |

c. 300–present[i] | Worldwide | 150–190 cm (4 ft 11 in – 6 ft 3 in) | 50–100 kg (110–220 lb) | 950–1,800 | (extant) | —— | 1758 |

| H. neanderthalensis |

240–40[25][j] | Europe, Western Asia | 170 cm (5 ft 7 in) | 55–70 kg (121–154 lb) (heavily built) |

1,200–1,900 | Many | 1829 | 1864 |

| H. floresiensis classification uncertain |

190–50 | Indonesia | 100 cm (3 ft 3 in) | 25 kg (55 lb) | 400 | 7 individuals | 2003 | 2004 |

| Nesher Ramla Homo classification uncertain |

140–120 | Israel | several individuals | 2021 | ||||

| H. tsaichangensis possibly H. erectus or Denisova |

c. 100[k] | Taiwan | 1 individual | 2008(?) | 2015 | |||

| H. luzonensis |

c. 67[28][29] | Philippines | 3 individuals | 2007 | 2019 | |||

| Denisova hominin | 40 | Siberia | 2 sites | 2000 |

2010[l] |

Migration and admixture

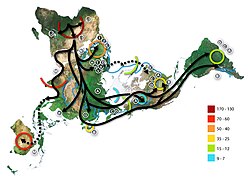

H. habilis, which is considered the first member of the genus Homo, gave rise to H. ergaster. Some of H. ergaster migrated to Asia, where they are named Homo erectus, and to Europe with Homo georgicus. H. ergaster in Africa and H. erectus in Eurasia evolved separately for almost two million years and presumably separated into two different species. Homo rhodesiensis, who were descended from H. ergaster, migrated from Africa to Europe and became Homo heidelbergensis and later (about 250,000 years ago) Homo neanderthalensis and the Denisova hominin in Asia. The first Homo sapiens, descendants of H. rhodesiensis, appeared in Africa about 250,000 years ago. About 100,000 years ago, some H. sapiens sapiens migrated from Africa to the Levant and met with resident Neanderthals, with some admixture.[30] Later, about 70,000 years ago, perhaps after the Toba catastrophe, a small group left the Levant to populate Eurasia, Australia and later the Americas. A subgroup among them met the Denisovans[31] and, after further admixture, migrated to populate Melanesia. In this scenario, non-African people living today are mostly of African origin ("Out of Africa model"). However, there was also some admixture with Neanderthals and Denisovans, who had evolved locally (the "multiregional hypothesis"). Recent genomic results from the group of Svante Pääbo also show that 30,000 years ago at least three major subspecies coexisted: Denisovans, Neanderthals and Cro-magnons.[32] Today, only H. sapiens sapiens remains, with no other extant species or subspecies.

See also

- Red Deer Cave people — tentative, unconfirmed as a separate species of cave dweller

References

- ^ Stringer, C.B. (1994). "Evolution of early humans". The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Human Evolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 242. ISBN 0-521-32370-3.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) Also ISBN 0-521-46786-1 (paperback) - ^ McHenry, H.M (2009). "Human Evolution". Evolution: The First Four Billion Years. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. p. 265. ISBN 978-0-674-03175-3.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ "Toothy Tree-Swinger May Be Earliest Human"

- ^ McPherron, S. P., Z. Alemseged, C. W. Marean, J. G. Wynn, D. Reed, D. Geraads, R. Bobe, and H. A. Bearat. 2010. Evidence for stone-tool-assisted consumption of animal tissues before 3.39 million years ago at Dikika, Ethiopia. Nature 466:857-860.

- ^ Mitchell, Alanna (January 30, 2012). "DNA Turning Human Story Into a Tell-All". NYTimes. Retrieved January 31, 2012.

- ^ Henry, Amanda G.; Ungar, Peter S.; Passey, Benjamin H.; Sponheimer, Matt; Rossouw, Lloyd; Bamford, Marion; Sandberg, Paul; de Ruiter, Darryl J.; Berger, Lee (June 27, 2012). "The diet of Australopithecus sediba". Nature (journal). doi:10.1038/nature11185. Retrieved June 28, 2012.

- ^ Boyle, Alan (June 27, 2012). "This pre-human ate like a chimp". MSNBC. Retrieved June 28., 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Wilford, John Noble (June 28, 2012). "Some Prehumans Feasted on Bark Instead of Grasses". New York Times. Retrieved June 28, 2012.

- ^ dhghem The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language: Fourth Edition. 2000.

- ^ Note: In 1959, Linnaeus was designated as the lectotype for Homo sapiens (Stearn, W. T. 1959. "The background of Linnaeus's contributions to the nomenclature and methods of systematic biology", Systematic Zoology 8 (1): 4-22, p. 4) which means that following the nomenclatural rules, Homo sapiens was validly defined as the animal species to which Linnaeus belonged.

- ^ Biological Anthropology: 2nd Edition. 2009. Craig Stanford et al.

- ^ Schrenk F, Kullmer O, Bromage T (2007). "The Earliest Putative Homo Fossils". In Henke W, Tattersall I (eds.). Handbook of Paleoanthropology. Vol. 1. In collaboration with Thorolf Hardt. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. pp. 1611–1631. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-33761-4_52. ISBN 978-3-540-32474-4.

- ^ DiMaggio EN, Campisano CJ, Rowan J, Dupont-Nivet G, Deino AL, Bibi F, et al. (March 2015). "Paleoanthropology. Late Pliocene fossiliferous sedimentary record and the environmental context of early Homo from Afar, Ethiopia". Science. 347 (6228): 1355–9. Bibcode:2015Sci...347.1355D. doi:10.1126/science.aaa1415. PMID 25739409. S2CID 43455561.

- ^ Curnoe D (June 2010). "A review of early Homo in southern Africa focusing on cranial, mandibular and dental remains, with the description of a new species (Homo gautengensis sp. nov.)". Homo. 61 (3): 151–77. doi:10.1016/j.jchb.2010.04.002. PMID 20466364.

- ^ Haviland WA, Walrath D, Prins HE, McBride B (2007). Evolution and Prehistory: The Human Challenge (8th ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth. p. 162. ISBN 978-0-495-38190-7.

- ^ Ferring R, Oms O, Agustí J, Berna F, Nioradze M, Shelia T, et al. (June 2011). "Earliest human occupations at Dmanisi (Georgian Caucasus) dated to 1.85-1.78 Ma". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 108 (26): 10432–6. Bibcode:2011PNAS..10810432F. doi:10.1073/pnas.1106638108. PMC 3127884. PMID 21646521.

- ^ Indriati E, Swisher CC, Lepre C, Quinn RL, Suriyanto RA, Hascaryo AT, et al. (2011). "The age of the 20 meter Solo River terrace, Java, Indonesia and the survival of Homo erectus in Asia". PLOS ONE. 6 (6): e21562. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...621562I. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0021562. PMC 3126814. PMID 21738710.

- ^ Hazarika M (2007). "Homo erectus/ergaster and Out of Africa: Recent Developments in Paleoanthropology and Prehistoric Archaeology" (PDF). EAA Summer School eBook. Vol. 1. European Anthropological Association. pp. 35–41.

Intensive Course in Biological Anthrpology, 1st Summer School of the European Anthropological Association, 16–30 June, 2007, Prague, Czech Republic

- ^ Muttoni G, Scardia G, Kent DV, Swisher CC, Manzi G (2009). "Pleistocene magnetochronology of early hominin sites at Ceprano and Fontana Ranuccio, Italy". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 286 (1–2): 255–268. Bibcode:2009E&PSL.286..255M. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2009.06.032.

- ^ Ji Q, Wu W, Ji Y, Li Q, Ni X (25 June 2021). "Late Middle Pleistocene Harbin cranium represents a new Homo species". The Innovation. 2 (3): 100132. doi:10.1016/j.xinn.2021.100132. PMC 8454552. PMID 34557772.

- ^ Ni X, Ji Q, Wu W, Shao Q, Ji Y, Zhang C, Liang L, Ge J, Guo Z, Li J, Li Q, Grün R, Stringer C (25 June 2021). "Massive cranium from Harbin in northeastern China establishes a new Middle Pleistocene human lineage". The Innovation. 2 (3): 100130. doi:10.1016/j.xinn.2021.100130. PMC 8454562. PMID 34557770.

- ^ Dirks PH, Roberts EM, Hilbert-Wolf H, Kramers JD, Hawks J, Dosseto A, et al. (May 2017). "Homo naledi and associated sediments in the Rising Star Cave, South Africa". eLife. 6: e24231. doi:10.7554/eLife.24231. PMC 5423772. PMID 28483040.

- ^ Callaway, Ewan (7 June 2017). "Oldest Homo sapiens fossil claim rewrites our species' history". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2017.22114. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- ^ Posth C, Wißing C, Kitagawa K, Pagani L, van Holstein L, Racimo F, et al. (July 2017). "Deeply divergent archaic mitochondrial genome provides lower time boundary for African gene flow into Neanderthals". Nature Communications. 8: 16046. Bibcode:2017NatCo...816046P. doi:10.1038/ncomms16046. PMC 5500885. PMID 28675384.

- ^ Bischoff JL, Shamp DD, Aramburu A, et al. (March 2003). "The Sima de los Huesos Hominids Date to Beyond U/Th Equilibrium (>350 kyr) and Perhaps to 400–500 kyr: New Radiometric Dates". Journal of Archaeological Science. 30 (3): 275–280. doi:10.1006/jasc.2002.0834. ISSN 0305-4403.

- ^ Dean D, Hublin JJ, Holloway R, Ziegler R (May 1998). "On the phylogenetic position of the pre-Neandertal specimen from Reilingen, Germany". Journal of Human Evolution. 34 (5): 485–508. doi:10.1006/jhev.1998.0214. PMID 9614635.

- ^ Chang CH, Kaifu Y, Takai M, Kono RT, Grün R, Matsu'ura S, et al. (January 2015). "The first archaic Homo from Taiwan". Nature Communications. 6: 6037. Bibcode:2015NatCo...6.6037C. doi:10.1038/ncomms7037. PMC 4316746. PMID 25625212.

- ^ Détroit F, Mijares AS, Corny J, Daver G, Zanolli C, Dizon E, et al. (April 2019). "A new species of Homo from the Late Pleistocene of the Philippines" (PDF). Nature. 568 (7751): 181–186. Bibcode:2019Natur.568..181D. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1067-9. PMID 30971845. S2CID 106411053.

- ^ Zimmer C (10 April 2019). "A new human species once lived in this Philippine cave – Archaeologists in Luzon Island have turned up the bones of a distantly related species, Homo luzonensis, further expanding the human family tree". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- ^ Green RE, Krause J, et al. A draft sequence of the Neandertal genome. Science. 2010 May 7;328(5979):710-22. doi:10.1126/science.1188021 PMID 20448178

- ^ ^ Reich D, Green RE, Kircher M, et al. (December 2010). "Genetic history of an archaic hominin group from Denisova Cave in Siberia". Nature 468 (7327): 1053–60. doi:10.1038/nature09710. PMID 21179161.

- ^ Reich D ., et al. Denisova admixture and the first modern human dispersals into southeast Asia and Oceania. Am J Hum Genet. 2011 Oct 7;89(4):516-28, doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.09.005 PMID 21944045.

- Serre; et al. (2004). "No evidence of Neandertal mtDNA contribution to early modern humans". PLoS Biology. 2 (3): 313–7. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020057. PMC 368159. PMID 15024415.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link)

External links

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).