Didinium: Difference between revisions

Makecat-bot (talk | contribs) m r2.7.3) (Robot: Adding ca:Didinium |

→Didinium nasutum: removed distracting & unnecessary links |

||

| Line 25: | Line 25: | ||

==''Didinium nasutum''== |

==''Didinium nasutum''== |

||

[[File:Didinium nasutum consuming a paramecium.jpg|thumb|320px|left|''Didinium nasutum'' consuming a paramecium. Illustration by S. O. Mast, 1909]] |

[[File:Didinium nasutum consuming a paramecium.jpg|thumb|320px|left|''Didinium nasutum'' consuming a paramecium. Illustration by S. O. Mast, 1909]] |

||

Much of what has been published about this genus is based on numerous studies of a single species, ''Didinium nasutum''. A voracious |

Much of what has been published about this genus is based on numerous studies of a single species, ''Didinium nasutum''. A voracious predator, ''D. nasutum'', uses specialized structures called [[toxicysts]] to ensnare and paralyze its ciliate prey. Once captured, the prey is engulfed through Didinium's expandible cytostome.<ref> {{cite journal | title = The Reactions of Didinium nasutum (Stein) with Special Reference to the Feeding Habits and the Function of Trichocysts | journal = Biological Bulletin | date = Feb 1909 | first = S. O. | last = Mast | volume = 16 | issue = 3 | pages = 96-112 | url = http://www.jstor.org/stable/1536126 . | accessdate = 04/09/2012}}</ref> |

||

While ''D. nasutum'' is sometimes described as feeding exclusively upon Paramecium, it has been shown that the organism will readily devour other ciliate species, including ''[[Colpoda]]'', ''Colpidium campylum'', ''[[Tetrahymena pyriformis]]'', ''[[Coleps|Coleps hirtus]]'' and ''[[Lacrymaria olor]]''.<ref> {{cite journal | title = The Feeding Behavior of Didinium nasutum on an Atypical Prey Ciliate (Colpidium campylum) | journal = Transactions of the American Microscopical Society | date = Oct 1979 | first = Jacques | last = Berger | volume = 98 | issue = 4 | pages = 487-94 | url = http://www.jstor.org/stable/3225898?origin=JSTOR-pdf | accessdate = 2012-09-07}}</ref> <ref> {{cite journal | title = The Reactions of Didinium nasutum (Stein) with Special Reference to the Feeding Habits and the Function of Trichocysts | journal = Biological Bulletin | date = Feb 1909 | first = S. O. | last = Mast | volume = 16 | issue = 3 | pages = 114 | url = http://www.jstor.org/stable/1536126 . | accessdate = 04/09/2012}}</ref> Moreover, strains of ''Didinium'' raised on a ''Colpidium campylum'' will actually show a preference for a diet made up of that species, as well as a diminished ability to kill and ingest Paramecia.<ref> {{cite journal | title = The Feeding Behavior of Didinium nasutum on an Atypical Prey Ciliate (Colpidium campylum) | journal = Transactions of the American Microscopical Society | date = Oct 1979 | first = Jacques | last = Berger | volume = 98 | issue = 4 | pages = 487-94 | url = http://www.jstor.org/stable/3225898?origin=JSTOR-pdf | accessdate = 2012-09-07}}</ref> |

While ''D. nasutum'' is sometimes described as feeding exclusively upon Paramecium, it has been shown that the organism will readily devour other ciliate species, including ''[[Colpoda]]'', ''Colpidium campylum'', ''[[Tetrahymena pyriformis]]'', ''[[Coleps|Coleps hirtus]]'' and ''[[Lacrymaria olor]]''.<ref> {{cite journal | title = The Feeding Behavior of Didinium nasutum on an Atypical Prey Ciliate (Colpidium campylum) | journal = Transactions of the American Microscopical Society | date = Oct 1979 | first = Jacques | last = Berger | volume = 98 | issue = 4 | pages = 487-94 | url = http://www.jstor.org/stable/3225898?origin=JSTOR-pdf | accessdate = 2012-09-07}}</ref> <ref> {{cite journal | title = The Reactions of Didinium nasutum (Stein) with Special Reference to the Feeding Habits and the Function of Trichocysts | journal = Biological Bulletin | date = Feb 1909 | first = S. O. | last = Mast | volume = 16 | issue = 3 | pages = 114 | url = http://www.jstor.org/stable/1536126 . | accessdate = 04/09/2012}}</ref> Moreover, strains of ''Didinium'' raised on a ''Colpidium campylum'' will actually show a preference for a diet made up of that species, as well as a diminished ability to kill and ingest Paramecia.<ref> {{cite journal | title = The Feeding Behavior of Didinium nasutum on an Atypical Prey Ciliate (Colpidium campylum) | journal = Transactions of the American Microscopical Society | date = Oct 1979 | first = Jacques | last = Berger | volume = 98 | issue = 4 | pages = 487-94 | url = http://www.jstor.org/stable/3225898?origin=JSTOR-pdf | accessdate = 2012-09-07}}</ref> |

||

In the absence of food, ''D. nasutum'' will encyst, lying [[dormancy|dormant]] within a protective |

In the absence of food, ''D. nasutum'' will encyst, lying [[dormancy|dormant]] within a protective coating.<ref> {{cite journal | title = Encystment and the Life Cycle in the Ciliate Didinium nasutum | journal = Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences | date = 15 Sept 1925 | first = C. Dale | last = Beers | volume = 11 | issue = 9 | pages = 525 | id = PMID PMC1086111}}</ref> In the laboratory, other environmental stimuli, such as the age of the growth medium or the accumulation of certain metabolic waste products, can also trigger [[encystment]].<ref> {{cite journal | title = Factors involved in encystment in the ciliate didinium nasutum | journal = Journal of Morphology | date = March 1927 | first = C. Dale | last = Beers | volume = 43 | issue = 2 | pages = 499-520 | doi = 10.1002/jmor.1050430208}}</ref> When the encysted form of ''D. nasutum'' is exposed to a vigorous culture of ''Paramecium'', it will excyst, reverting to its active, swimming form.<ref> {{cite journal | title = Conjugation and encystment in Didinium nasutum with especial reference to their significance | journal = Journal of Experimental Zoology | date = July 1917 | first = S. O. | last = Mast | volume = 23 | issue = 2 | pages = 340 | doi = 10.1002/jez.1400230206}}</ref> |

||

Didinium [[cyst]]s have been shown to remain viable for at least 10 years.<ref> {{cite journal | title = The Viability of Ten-Year-Old Didinium Cysts (Infusoria) | journal = The American Naturalist | date = Sept-Oct 1937 | first = C. Dale | last = Beers | volume = 71 | issue = 736 | pages = 521-4 | url = http://www.jstor.org/stable/2457306}}</ref> |

Didinium [[cyst]]s have been shown to remain viable for at least 10 years.<ref> {{cite journal | title = The Viability of Ten-Year-Old Didinium Cysts (Infusoria) | journal = The American Naturalist | date = Sept-Oct 1937 | first = C. Dale | last = Beers | volume = 71 | issue = 736 | pages = 521-4 | url = http://www.jstor.org/stable/2457306}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 14:30, 10 February 2013

| Didinium | |

|---|---|

| |

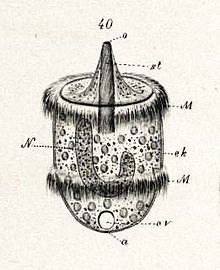

| Didinium nasutum as illustrated by Schewiakoff, 1896 | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | |

| Superphylum: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Didinium Stein, 1859

|

Didinium is a genus of unicellular ciliate protists with at least ten accepted species. All are free-living carnivores. Most are found in fresh and brackish water, but three marine species are known. Their diet consists largely of Paramecium, although they will also attack and consume other ciliates.[1] Some species, such as D. gargantua, also feed on non-ciliate protists, including dinoflagellates, cryptomonads, and green algae. [2]

Appearance and reproduction

Didinia are rounded, oval or barrel-shaped and range in length from 50 to 150 micrometres. [3] The cell body is encircled by two ciliary bands, or pectinelles. This distinguishes them from the related genus Monodinium, which have only a single band, except during cell division.[4] The pectinelles are used to move Didinium through water by rotating the cell around its axis.[5] At the anterior end, a cone-shaped structure protrudes, supported by a palisade of stiff microtubular rods (nematodesmata). This cone encloses the cytostome or "mouth" opening, as in other haptorian ciliates. The dimensions of this protuberance vary among the different species.

The macronucleus is long, and may be curved, horseshoe-shaped or twisted into a shape resembling a figure eight.[6] A contractile vacuole and anal aperture are in the posterior of the cell.[7]

Like all ciliates, Didinia reproduce asexually via binary fission, or sexually through conjugation.

Didinium nasutum

Much of what has been published about this genus is based on numerous studies of a single species, Didinium nasutum. A voracious predator, D. nasutum, uses specialized structures called toxicysts to ensnare and paralyze its ciliate prey. Once captured, the prey is engulfed through Didinium's expandible cytostome.[8]

While D. nasutum is sometimes described as feeding exclusively upon Paramecium, it has been shown that the organism will readily devour other ciliate species, including Colpoda, Colpidium campylum, Tetrahymena pyriformis, Coleps hirtus and Lacrymaria olor.[9] [10] Moreover, strains of Didinium raised on a Colpidium campylum will actually show a preference for a diet made up of that species, as well as a diminished ability to kill and ingest Paramecia.[11]

In the absence of food, D. nasutum will encyst, lying dormant within a protective coating.[12] In the laboratory, other environmental stimuli, such as the age of the growth medium or the accumulation of certain metabolic waste products, can also trigger encystment.[13] When the encysted form of D. nasutum is exposed to a vigorous culture of Paramecium, it will excyst, reverting to its active, swimming form.[14]

Didinium cysts have been shown to remain viable for at least 10 years.[15]

History and classification

Didinium was discovered by the eighteenth-century naturalist O.F. Müller and described in his Animalcula Infusoria under the name Vorticella nasuta.[16] In 1859, Samuel Friedrich Stein moved the species to the newly created genus Didinium, which he placed within the order Peritricha, alongside other ciliates which have a ciliary fringe at the anterior of the cell, (such as Vorticella and Cothurnia.[17] Later in the century, under the taxonomical scheme created by Otto Bütschli, Didinium was removed from among the Peritrichs, and placed in the order Holotricha.[18] In 1974, John. O. Corliss created the order Haptorida, within the subclass Haptoria, for "rapacious carnivorous forms" such as Didinium, Dileptus and Spathidium.[19] This group has since been placed in the class Litostomatea Small & Lynn, 1981.

Genetic analysis of Haptorian ciliates has shown that they do not form a monophyletic group.[20][21]

List of Species

Didinium alveolatum Kahl, 1930

Didinium armatum Penard, 1922

Didinium balbianii Fabre-Domergue, 1888

Didinium bosphoricum Hovasse, 1932

Didinium chlorelligerum Kahl, 1935

Didinium faurei Kahl, 1930

Didinium gargantua Meunier, 1910

Didinium impressum Kahl, 1926

Didinium minimum

Didinium nasutum(Müller, 1773) Stein, 1859

References

- ^ Berger, Jacques (Oct 1979). "The Feeding Behavior of Didinium nasutum on an Atypical Prey Ciliate (Colpidium campylum)". Transactions of the American Microscopical Society. 98 (4): 487–94. Retrieved 2012-09-07.

- ^ "Didinium Gargantua". Planktonic Ciliate Project on the Internet. University of Liverpool School of Biological Sciences. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- ^ Kahl, Alfred (1930–35). Urtiere oder Protozoa I: Wimpertiere oder Ciliata (Infusoria) In: Die Tierwelt Deutschlands. Vol. 1. Allgemeiner teil und Prostomata. Jena: G. Fischer. pp. 123–6.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ Lee, John J.; et al. (2000). An Illustrated Guide to the Protozoa: organisms traditionally referred to as protozoa, or newly discovered groups. Vol. 1 (2 ed.). Lawrence, Kansas: Society of Protozoologists. pp. 480–1. ISBN 1-891276-22-0.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Explicit use of et al. in:|first1=(help); Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ Mast, S. O. (Feb 1909). . "The Reactions of Didinium nasutum (Stein) with Special Reference to the Feeding Habits and the Function of Trichocysts". Biological Bulletin. 16 (3): 92–3. Retrieved 04/09/2012.

{{cite journal}}: Check|url=value (help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Mast, S. O. (Feb 1909). . "The Reactions of Didinium nasutum (Stein) with Special Reference to the Feeding Habits and the Function of Trichocysts". Biological Bulletin. 16 (3): 92. Retrieved 04/09/2012.

{{cite journal}}: Check|url=value (help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Kent, William Saville (1881-2). A Manual of the Infusoria. Vol. 2. London: David Bogue. pp. 638–9.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Mast, S. O. (Feb 1909). . "The Reactions of Didinium nasutum (Stein) with Special Reference to the Feeding Habits and the Function of Trichocysts". Biological Bulletin. 16 (3): 96–112. Retrieved 04/09/2012.

{{cite journal}}: Check|url=value (help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Berger, Jacques (Oct 1979). "The Feeding Behavior of Didinium nasutum on an Atypical Prey Ciliate (Colpidium campylum)". Transactions of the American Microscopical Society. 98 (4): 487–94. Retrieved 2012-09-07.

- ^ Mast, S. O. (Feb 1909). . "The Reactions of Didinium nasutum (Stein) with Special Reference to the Feeding Habits and the Function of Trichocysts". Biological Bulletin. 16 (3): 114. Retrieved 04/09/2012.

{{cite journal}}: Check|url=value (help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Berger, Jacques (Oct 1979). "The Feeding Behavior of Didinium nasutum on an Atypical Prey Ciliate (Colpidium campylum)". Transactions of the American Microscopical Society. 98 (4): 487–94. Retrieved 2012-09-07.

- ^ Beers, C. Dale (15 Sept 1925). "Encystment and the Life Cycle in the Ciliate Didinium nasutum". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 11 (9): 525. PMID PMC1086111.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Beers, C. Dale (March 1927). "Factors involved in encystment in the ciliate didinium nasutum". Journal of Morphology. 43 (2): 499–520. doi:10.1002/jmor.1050430208.

- ^ Mast, S. O. (July 1917). "Conjugation and encystment in Didinium nasutum with especial reference to their significance". Journal of Experimental Zoology. 23 (2): 340. doi:10.1002/jez.1400230206.

- ^ Beers, C. Dale (Sept-Oct 1937). "The Viability of Ten-Year-Old Didinium Cysts (Infusoria)". The American Naturalist. 71 (736): 521–4.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Müller, O.F. Animalcula Infusoria, Fluvia Tilia et Marina. 1786. Hauniae, Typis N. Mölleri. pp. 268-9.

- ^ Stein, Friedrich (1859, 1867). Der Organismus der Infusionsthiere (1859) (PDF). Leipzig: W. Engelmann.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Bütschli, Otto (1887-9). ERSTER BAND. PROTOZOA. Vol. III. Leipzig & Heidelberg: C. F. Winter,. p. 1688.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help); Check date values in:|year=(help); Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Corliss, John O. (May 1974). "Remarks on the Composition of the Large Ciliate Class Kinetofragmophora de Puytorac et al., 1974, and Recognition of Several New Taxa Therein, with Emphasis on the Primitive Order Primociliatida N. Ord". Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiolog. 21 (2). doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.1974.tb03643.x.

- ^ Gao, S (Nov–Dec 2008). "Phylogeny of six genera of the subclass Haptoria (Ciliophora, Litostomatea) inferred from sequences of the gene coding for small subunit ribosomal RNA". Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. 55 (6): 562–6. PMID 19120803.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ Vd'ačný, Peter (2011). "Phylogeny and Classification of the Litostomatea (Protista, Ciliophora), with Emphasis on Free-Living Taxa and the 18S rRNA Gene". Mol Phylogenet Evol. 59 (2): 510–22. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2011.02.016. PMID 21333743.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)