Lovastatin: Difference between revisions

| Line 199: | Line 199: | ||

*Altocor |

*Altocor |

||

*Altoprev |

*Altoprev |

||

}} |

|||

==Other applications== |

==Other applications== |

||

Revision as of 14:49, 6 June 2013

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Mevacor |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a688006 |

| Routes of administration | oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | <5% |

| Protein binding | >95% |

| Metabolism | hepatic (CYP3A substrate) |

| Elimination half-life | 1.1-1.7 hours |

| Excretion | negligible |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.115.931 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

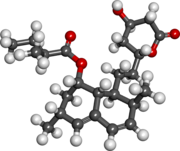

| Formula | C24H36O5 |

| Molar mass | 404.54 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Lovastatin (Merck's Mevacor) is a member of the drug class of statins, used in combination with diet, weight-loss, and exercise for lowering cholesterol (hypolipidemic agent) in those with hypercholesterolemia to reduce risk of cardiovascular disease. Lovastatin is a naturally occurring drug found in food such as oyster mushrooms[1] and red yeast rice.[2]

Medical uses

The primary uses of lovastatin is for the treatment of dyslipidemia and the prevention of cardiovascular disease.[3] It is recommended to be used only after other measures, such as diet, exercise, and weight reduction, have not improved cholesterol levels.[3]

History

Compactin and lovastatin, natural products with a powerful inhibitory effect on HMG-CoA reductase, were discovered in the 1970s, and taken into clinical development as potential drugs for lowering LDL cholesterol.[5][6]

In 1982, some small-scale clinical investigations of lovastatin, a polyketide-derived natural product isolated from Aspergillus terreus, in very high-risk patients were undertaken, in which dramatic reductions in LDL cholesterol were observed, with very few adverse effects. After the additional animal safety studies with lovastatin revealed no toxicity of the type thought to be associated with compactin, clinical studies continued.

Large-scale trials confirmed the effectiveness of lovastatin. Observed tolerability continued to be excellent, and lovastatin was approved by the US FDA in 1987.[7] It was the first statin approved by the FDA.[8]

Lovastatin at its maximal recommended dose of 80 mg daily produced a mean reduction in LDL cholesterol of 40%, a far greater reduction than could be obtained with any of the treatments available at the time. Equally important, the drug produced very few adverse effects and was easy for patients to take, so was rapidly accepted by prescribers and patients. The most significant adverse effect is rhabdomyolysis; this is rare and may occur with the use of any HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor.

Lovastatin is also naturally produced by certain higher fungi, such as Pleurotus ostreatus (oyster mushroom) and closely related Pleurotus spp.[9] Research into the effect of oyster mushroom and its extracts on the cholesterol levels of laboratory animals has been extensive,[10][11][9][12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20] although the effect has been demonstrated in a very limited number of human subjects.[21]

In 1998, the FDA placed a ban on the sale of dietary supplements derived from red yeast rice, which naturally contains lovastatin, arguing that products containing prescription agents require drug approval.[citation needed] This ban was subsequently rescinded, in light of law that upholds that natural products are not patentable.

Mechanism of action

Lovastatin is an inhibitor of 3-hydroxy-3methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase (HMG-CoA reductase), an enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of HMG-CoA to mevalonate.[22] Mevalonate is a required building block for cholesterol biosynthesis and lovastatin interferes with its production by acting as a reversible competitive inhibitor for HMG-CoA, which binds to the HMG-CoA reductase. Lovastatin, being inactive in the native form, the form in which it is administered, is hydrolysed to the β-hydroxy acid form in the body; this is the active form.

Discovery, biochemistry and biology

An elevated concentration of plasma cholesterol, especially low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, is now generally accepted as a major risk factor for the development of coronary heart disease.[23] The objective is to decrease excess levels of cholesterol to an amount consistent with maintenance of normal body function. Cholesterol is biosynthesized in a series of more than 25 separate enzymatic reactions that initially involves three successive condensations of acetyl-CoA units to form the six-carbon compound 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG CoA). This is reduced to mevalonate and then converted in a series of reactions to the isoprenes that are building-blocks of squalene, the immediate precursor to sterols, which cyclizes to lanosterol (a methylated sterol) and further metabolized to cholesterol. A number of early attempts to block the synthesis of cholesterol resulted in agents that inhibited late in the biosynthetic pathway between lanosterol and cholesterol. A major rate-limiting step in the pathway is at the level of the microsomal enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of HMG CoA to mevalonic acid, and that has been considered to be a prime target for pharmacologic intervention for several years.[22]

HMG CoA reductase occurs early in the biosynthetic pathway and is among the first committed steps to cholesterol formulation. Inhibition of this enzyme could lead to accumulation of HMG CoA, a water-soluble intermediate that is, then, capable of being readily metabolized to simpler molecules. This inhibition of reductase would lead to accumulation of lipophylic intermediates with a formal sterol ring.

Lovastatin was the first specific inhibitor of HMG CoA reductase to receive approval for the treatment of hypercholesterolemia. The first breakthrough in efforts to find a potent, specific, competitive inhibitor of HMG CoA reductase occurred in 1976, when Endo et al. reported the discovery of mevastatin, a highly functionalized fungal metabolite, isolated from cultures of Penicillium citrium.[24] Mevastatin was demonstrated to be an unusually potent inhibitor of the target enzyme and of cholesterol biosynthesis. Subsequent to the first reports describing mevastatin, efforts were initiated to search for other naturally occurring inhibitors of HMG CoA reductase. This led to the discovery of a novel fungal metabolite – lovastatin. The structure of lovastatin was determined to be different from that of mevastatin by the presence of a six alphamethyl group in the hexahydronaphthalene ring.

Key points from the study of the biosynthesis of lovastatin:

- Lovastatin is composed of two polyketide chains derived from acetate, two and four carbons long, coupled in head-to-tail fashion.

- The six alphamethyl group and the methyl group on the four-carbon side-chain are derived from the methyl group of methionine.

- The six alphamethyl group is added before closure of the rings.

This implies that lovastatin is a unique compound synthesized by A. terreus and that mevastatin is not an intermediate in its formation.

Biosynthesis using Diels-Alder catalyzed cyclization

In vitro formation of a triketide lactone using a genetically modified protein derived from 6-deoxyerythronolide B synthase has been demonstrated. Witter and Vederas observed, "the stereochemistry of the molecule supports the intriguing idea that an enzyme-catalyzed Diels-Alder reaction may occur during assembly of the polyketide chain. It, thus, appears that biological Diels-Alder reactions may be triggered by generation of reactive triene systems on an enzyme surface."[25]

Total synthesis

A major bulk of work in the synthesis of lovastatin was done by M. Hirama in the 1980s.[26] [27] Hirama synthesized compactin and used one of the intermediates to follow a different path to get to lovastatin. The synthetic sequence is shown in the schemes below. The γ-lactone was synthesized using Yamada methodology starting with glutamic acid. Lactone opening was done using lithium methoxide in methanol and then silylation to give a separable mixture of the starting lactone and the silyl ether. The silyl ether on hydrogenolysis followed by Collins oxidation gave the aldehyde. Stereoselective preparation of (E,E)-diene was accomplished by addition of trans-crotyl phenyl sulfone anion, followed by quenching with Ac2O and subsequent reductive elimination of sulfone acetate. Condensation of this with lithium anion of dimethyl methylphosphonate gave compound 1. Compound 2 was synthesized as shown in the scheme in the synthetic procedure. Compounds 1 and 2 were then combined together using 1.3 eq sodium hydride in THF followed by reflux in chlorobenzene for 82 hr under nitrogen to get the enone 3.

Simple organic reactions were used to get to lovastatin as shown in the scheme.

Pharmacology and dose

The mode of action of statins is HMG-CoA reductase enzyme inhibition. This enzyme is needed by the body to make cholesterol.

Lovastatin causes cholesterol to be lost from LDL, but also reduces the concentration of circulating LDL particles. Apolipoprotein B concentration falls substantially during treatment with lovastatin. Lovastatin's ability to lower LDL is thought to be due to a reduction in VLDL, which is a precursor to LDL. Also, lovastatin may increase the number of LDL receptors on the surface of cell membranes, and thus increase the breakdown of LDL.

Lovastatin can also produce slight to moderate increases in HDL, and slight to moderate decreases in triglycerides. Both of these effects are typically beneficial to a patient with a poor lipid profile.

Both lovastatin and its b-hydroxyacid metabolite are highly bound (>95%) to human plasma proteins. Animal studies demonstrated that lovastatin crosses the blood-brain and placental barriers.[28] Elderly patients, or those with renal insufficiency, may have higher plasma concentrations of lovastatin after administration and may require a lower dose. The usual recommended starting dose is 20 mg once a day given with the evening meal, and the dose range is 10–80 mg a day in a single dose, or divided into two doses.

Lovastatin and other statins have recently been studied for their chemopreventive and chemotherapeutic effects in certain cancers. However, based on clinical evidence, such effects could not be demonstrated.[29] In principle, independent of their hydroxymethyl glutaryl (HMG)-CoA reductase inhibition, lovastatin and other statins reduce proteasome activity, leading to an accumulation of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors p21 and p27, and G1 phase arrest in breast cancer cell lines. For that purpose, lovastatin is also used experimentally.[30]

Side effects and contraindications

Lovastatin is usually well tolerated. As with all statin drugs, it can rarely cause myopathy or rhabdomyolysis. This can be life-threatening if not recognised and treated in time, so any unexplained muscle pain or weakness whilst on lovastatin should be promptly mentioned to the prescribing doctor. Other uncommon side effects that should be promptly mentioned to either the prescribing doctor or an emergency medical service include:[31]

These less serious side effects should still be reported if they persist or increase in severity:[31]

Contraindications, conditions that warrant withholding treatment with lovastatin, include pregnancy, breast feeding, and liver disease. Lovastatin is contraindicated during pregnancy (Pregnancy Category X); it may cause birth defects such as skeletal deformities or learning disabilities. Due to its potential to disrupt infant lipid metabolism, lovastatin should not be taken while breastfeeding.[32] Patients with liver disease should not take lovastatin.[33]

Drug interactions

As with atorvastatin, simvastatin, and other statin drugs metabolized via CYP3A4, drinking grapefruit juice during lovastatin therapy may increase the risk of side effects. Components of grapefruit juice, the flavonoid naringin, or the furanocoumarin bergamottin inhibit CYP3A4 in vitro,[34] and may account for the in vivo effect of grapefruit juice concentrate decreasing the metabolic clearance of lovastatin, and increasing its plasma concentrations.[35]

Lovastatin at doses higher than 20 mg per day should not be used in conjunction with gemfibrozil (Lopid) or other fibrates, niacin, or cyclosporine, because of the significantly increased risk of rhabdomyolysis. Additional drugs that should not be taken alongside lovastatin include, but are not limited to: cholestyramine (Questran), colestipol (Colestid), and danazol (Danocrine).[33]

Pharmacopoeia information

Lovastatin tablets are preserved when stored in well-closed, light-resistant containers in a cool place or at controlled room temperature.

Lovastatin tablets are tested for dissolution and assay as per the USP.

Limit for dissolution – Not less than 80% (Q) of the labeled amount of lovastatin is dissolved in 30 minutes.

Limit for assay – Each tablet contains not less than 90% and not more than 110% of the labeled amount of lovastatin, tested by HPLC analysis.

Brand names

Other applications

In plant physiology, lovastatin has occasionally been used as inhibitor of cytokinin biosynthesis.[36]

Lovastatin is currently in phase one of clinical trial (NCT00352599) to evaluate safety for treatment of cognitive deficits in patients with neurofibromatosis type I. This drug has been shown to reverse spatial deficits in mice.[37]

See also

References

- ^ .

Gunde-Cimerman N, Cimerman A. (1995). "Pleurotus fruiting bodies contain the inhibitor of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase-lovastatin". Exp Mycol. 19 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1006/emyc.1995.1001. PMID 7614366.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Liu J, Zhang J, Shi Y, Grimsgaard S, Alraek T, Fønnebø V (2006). "Chinese red yeast rice (Monascus purpureus) for primary hyperlipidemia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Chin Med. 1: 4. doi:10.1186/1749-8546-1-4. PMC 1761143. PMID 17302963.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b "Lovastatin". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- ^ Alarcón J, Aguila S, Arancibia-Avila P, Fuentes O, Zamorano-Ponce E, Hernández M (2003 Jan-Feb). "Production and purification of statins from Pleurotus ostreatus (Basidiomycetes) strains". Z Naturforsch C. 58 (1–2): 62–4. PMID 12622228.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Vederas JC, Moore RN, Bigam G, Chan KJ (1985). "Biosynthesis of the hypocholesterolemic agent mevinolin by Aspergillus terreus. Determination of the origin of carbon, hydrogen and oxygen by 13C NMR and mass spectrometry". J Am Chem Soc. 107 (12): 3694–701. doi:10.1021/ja00298a046.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Alberts AW, Chen J, Kuron G, Hunt V, Huff J, Hoffman C, Rothrock J, Lopez M, Joshua H, Harris E, Patchett A, Monaghan R, Currie S, Stapley E, Albers-Schonberg G, Hensens O, Hirshfield J, Hoogsteen K, Liesch J, Springer J (July 1980). "Mevinolin: a highly potent competitive inhibitor of hydroxymethlglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase and a cholesterol-lowering agent". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 77 (7): 3957–61. doi:10.1073/pnas.77.7.3957. PMC 349746. PMID 6933445.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ FDA Orange Book Detail for application N019643 showing approval for 20 mg tablets on Aug 31, 1987 and 40 mg tablets on Dec 14, 1988

- ^ Endo, Akira (2004). "The origin of the statins". Atheroscler Suppl. 5 (3): 125–30. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosissup.2004.08.033. PMID 15531285.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Bobek P, Ozdín L, Galbavý S (1998). "Dose- and time-dependent hypocholesterolemic effect of oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) in rats". Nutrition. 14 (3): 282–6. doi:10.1016/S0899-9007(97)00471-1. PMID 9583372.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Cite error: The named reference "pmid9583372" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Hossain S, Hashimoto M, Choudhury EK; et al. (2003). "Dietary mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) ameliorates atherogenic lipid in hypercholesterolaemic rats". Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 30 (7): 470–5. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1681.2003.03857.x. PMID 12823261.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bobek P, Galbavý S (1999). "Hypocholesterolemic and antiatherogenic effect of oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) in rabbits". Nahrung. 43 (5): 339–42. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1521-3803(19991001)43:5<339::AID-FOOD339>3.0.CO;2-5. PMID 10555301.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Opletal L, Jahodár L, Chobot V; et al. (1997). "Evidence for the anti-hyperlipidaemic activity of the edible fungus Pleurotus ostreatus". Br. J. Biomed. Sci. 54 (4): 240–3. PMID 9624732.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bajaj M, Vadhera S, Brar AP, Soni GL (1997). "Role of oyster mushroom (Pleurotus florida) as hypocholesterolemic/antiatherogenic agent". Indian J. Exp. Biol. 35 (10): 1070–5. PMID 9475042.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bobek P, Ozdín L, Kuniak L, Hromadová M (1997). "[Regulation of cholesterol metabolism with dietary addition of oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus) in rats with hypercholesterolemia]". Cas. Lek. Cesk. (in Slovak). 136 (6): 186–90. PMID 9221192.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bobek P, Ozdín L, Kuniak L (1996). "Effect of oyster mushroom (Pleurotus Ostreatus) and its ethanolic extract in diet on absorption and turnover of cholesterol in hypercholesterolemic rat". Nahrung. 40 (4): 222–4. doi:10.1002/food.19960400413. PMID 8810086.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bobek P, Ozdín O, Mikus M (1995). "Dietary oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) accelerates plasma cholesterol turnover in hypercholesterolaemic rat". Physiol Res. 44 (5): 287–91. PMID 8869262.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bobek P, Ozdin L, Kuniak L (1995). "The effect of oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus), its ethanolic extract and extraction residues on cholesterol levels in serum, lipoproteins and liver of rat". Nahrung. 39 (1): 98–9. doi:10.1002/food.19950390113. PMID 7898579.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bobek P, Ozdin L, Kuniak L (1994). "Mechanism of hypocholesterolemic effect of oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) in rats: reduction of cholesterol absorption and increase of plasma cholesterol removal". Z Ernahrungswiss. 33 (1): 44–50. doi:10.1007/BF01610577. PMID 8197787.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Chorváthová V, Bobek P, Ginter E, Klvanová J (1993). "Effect of the oyster fungus on glycaemia and cholesterolaemia in rats with insulin-dependent diabetes". Physiol Res. 42 (3): 175–9. PMID 8218150.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bobek P, Ginter E, Jurcovicová M, Kuniak L (1991). "Cholesterol-lowering effect of the mushroom Pleurotus ostreatus in hereditary hypercholesterolemic rats". Ann. Nutr. Metab. 35 (4): 191–5. doi:10.1159/000177644. PMID 1897899.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Khatun K, Mahtab H, Khanam PA, Sayeed MA, Khan KA (2007). "Oyster mushroom reduced blood glucose and cholesterol in diabetic subjects". Mymensingh Med J. 16 (1): 94–9. doi:10.3329/mmj.v16i1.261. PMID 17344789.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Alberts AW (1998). "Discovery, biochemistry and biology of lovastatin". The American Journal of Cardiology. 62 (15): 10J–15J. doi:10.1016/0002-9149(88)90002-1. PMID 3055919.

- ^ Coronary heart disease: MedLine Plus Medical Encyclopedia

- ^ Endo, Akira (1976). "ML-236A, ML-236B, and ML-236C, new inhibitors of cholesterogenesis produced by Penicillium citrinium". Journal of Antibiotics (Tokyo). 29 (12): 1346–8. doi:10.7164/antibiotics.29.1346. PMID 1010803.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Witter, DJ (1996). "Putative Diels-Alder catalyzed cyclization during the biosynthesis of lovastatin". J Org Chem. 61 (8): 2613–23. doi:10.1021/jo952117p. PMID 11667090.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Hirama M, Vet M (1982). "A chiral total synthesis of compactin". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 104 (15): 4251. doi:10.1021/ja00379a037.

- ^ Hirama M, Iwashita; Iwashita, Mitsuko (1983). "Synthesis of (+)-Mevinolin starting from Naturally occurring building blocks and using an asymmetry inducing reaction". Tetrahedron Lett. 24 (17): 1811–1812. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)81777-3.

- ^ "Lovastatin". Rxlist.com.

- ^ Katz, MS (2005). "Therapy insight: Potential of statins for cancer chemoprevention and therapy". Nature clinical practice. Oncology. 2 (2): 82–9. doi:10.1038/ncponc0097. PMID 16264880.

- ^ Rao S, Porter DC, Chen X, Herliczek T, Lowe M, Keyomarsi K (1999). "Lovastatin-mediated G1 arrest is through inhibition of the proteasome, independent of hydroxymethyl glutaryl-CoA reductase". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96 (14): 7797–802. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.14.7797. PMC 22141. PMID 10393901.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Lovastatin". MedlinePlus. U.S. National Library of Medicine. 15 June 2012. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- ^ "Lovastatin". LactMed. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- ^ a b Stöppler, Melissa. "Mevacor Side Effects Center". RxList. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- ^ David G. Bailey, J. Malcolm, O. Arnold, J. David Spence (1998). "Grapefruit juice-drug interactions". Br J Clin Pharmacol 46 (2): 101–110. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2125.1998.00764.x. PMC 1873672. PMID 9723817.

- ^ Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1998 Apr;63(4):397-402. Grapefruit juice greatly increases serum concentrations of lovastatin and lovastatin acid. Kantola T, Kivistö KT, Neuvonen PJ. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9585793

- ^ Hartig K, Beck E (2005). "Assessment of lovastatin application as tool in probing cytokinin-mediated cell cycle regulation". Physiologia Plantarum. 125 (2): 260–267. doi:10.1111/j.1399-3054.2005.00556.x.

- ^ "Trial to Evaluate the Safety of Lovastatin in Individuals With Neurofibromatosis Type I (NF1)"