Boko Haram: Difference between revisions

Undid revision 624742853 by 71.10.224.33 (talk)UK |

|||

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

{{quote|"Since Boko Haram’s resurgence in 2010, the Nigerian government has struggled to respond to the growing threat posed by the group." (US [[Congressional Research Service|CRS]], 2014)<ref name="Congressional"/>}} |

{{quote|"Since Boko Haram’s resurgence in 2010, the Nigerian government has struggled to respond to the growing threat posed by the group." (US [[Congressional Research Service|CRS]], 2014)<ref name="Congressional"/>}} |

||

== |

==Backgrounding== |

||

===History=== |

===History=== |

||

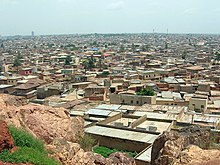

[[File:KanofromDalaHill.jpg|thumb|Kano]] |

[[File:KanofromDalaHill.jpg|thumb|Kano]] |

||

Revision as of 10:34, 9 September 2014

| والجهاد للدعوة السنة أهل جماعة People Committed to the Prophet's Teachings for Propagation and Jihad | |

|---|---|

| File:Logo of Boko Haram.svg | |

| Leaders | Abubakar Shekau Mohammed Yusuf † |

| Dates of operation | 2002–present |

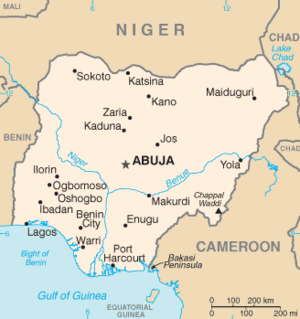

| Active regions | |

| Ideology | Wahhabi Salafi Jihadism Sunni Islamic fundamentalism |

| Allies | File:AQMI logo.png Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb |

| Opponents | |

| Battles and wars | Nigerian Sharia conflict |

Boko Haram (Western education is forbidden), Jama'atu Ahlis Sunna Lidda'Awati Wal-Jihad, is a militant Islamist movement based in northeast Nigeria. The group has received training and funds from Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, and was designated by the US as a terrorist organisation in November 2013. Membership has been estimated to number between a few hundred and a few thousand.[2][3][4]

Boko Haram killed more than 5,000 civilians between July 2009 and June 2014, including at least 2,000 in the first half of 2014, in attacks occuring mainly in northeast, northcentral and central states.[5][6][7] Corruption in the security services and human rights abuses committed by them have hampered efforts to counter the unrest.[8][9] 650,000 people fled the conflict zone by August 2014, an increase of 200,000 since May.[10]

"Since Boko Haram’s resurgence in 2010, the Nigerian government has struggled to respond to the growing threat posed by the group." (US CRS, 2014)[4]

Backgrounding

History

Nigeria was governed by a series of ruthless military dictatorships from its independence in 1960 until the advent of democracy in 1999. Ethnic militancy is thought to have been one of the causes of the 1967-70 civil war; religious violence reached a new height in 1980 in Kano, the largest city in the north of the country, where the Muslim fundamentalist sect Yan Tatsine ("followers of Maitatsine") instigated riots that resulted in four or five thousand deaths. In the ensuing military crackdown Maitatsine was killed, causing a backlash of increased violence which spread across other northern cities over the course of the next 20 years.[11]

Mohammed Yusuf founded the sect that became known as Boko Haram in 2002 in Maiduguri, the capital of the north-eastern state of Borno, establishing a religious complex with a school which attracted poor Muslim families from across Nigeria and neighbouring countries. The center had the political goal of creating an Islamic state, and became a recruiting ground for jihadis. By denouncing the police and state corruption Yusuf attracted followers from unemployed youths.[12][13][14][15]

He is reported to have used the existing infrastructure in Borno of the Izala Society (Jama'at Izalatil Bidiawa Iqamatus Sunnah), a popular conservative Islamic sect, to recruit members, before breaking away to form his own faction. The Izala were originally welcomed into government, along with people sympathetic to Yusuf. The Council of Ulama advised the government and the Nigerian Television Authority not to broadcast Yusuf's preaching, but their warnings were ignored. Yusuf's arrests elevated him to hero status.[16]

Inequality and the increasingly radical nature of Islam, locally and internationally, beginning with the 1979 Ayatollah Khomeini revolution in Iran, contributed both to the Maitatsine and the Boko Haram uprisings. Local politicians in Nigeria have the authority to grant 'indigeneship', which determines whether citizens can participate in politics, own land or work. The system has been widely abused. It has been an aggravating factor in riots with combined ethnic and religious dimensions in which hundreds or thousands were killed and tens of thousands forced to flee their homes, for example in Zangon-Kataf in 1992, and in Jos in 2002 and 2008.[17][18]: 97–98 [19]

Borno's Deputy Governor Alhaji Dibal has claimed that Al Qaida had ties with Boko Haram, but broke them when they decided that Yusuf was an unreliable person.[16] The violence of Boko Haram has also been linked to the militancy of the Arewa People's Congress, the militia wing of the Arewa Consultative Forum, the main political group representing the interests of northern Nigeria. For decades, Northern politicians and academics have voiced their fundamental opposition to Western education. The ACF is a well-funded group with military and intelligence expertise, and is considered capable of engaging in military action, including covert bombing. Co-founder of the APC, Sagir Mohammed, has stated:

“We believe we have the capacity, the willpower to go to any part of Nigeria to protect our Northern brothers in distress. . .If it becomes necessary, if we have to use violence, we have to use it to save our people. If it means jihad, we will launch our jihad.”[20]

Ideology

Boko Haram was founded as a Sunni Islamic fundamentalist sect advocating a strict form of sharia law and developed into a Salafist-jihadi group in 2009, influenced by the Wahhabi movement.[4][21][22][23][24][25] It seeks the establishment of an Islamic state in Nigeria, and opposes the Westernising of Nigerian society that has concentrated the wealth of the country among a small political elite, mainly in the Christian south of the country.[26][27] Nigeria is Africa's biggest economy; 60% of its population of 173 million (2013) live on less than $1 a day.[28][29][30] The sharia law imposed by local authorities, beginning with Zamfara in January 2000 and covering 12 northern states by late 2002, may have promoted links between Boko Haram and political leaders, but was considered by the group to have been corrupted.[18]: 101 [31][32][33]

Boko Haram kill people who engage in practices seen as un-Islamic, such as drinking alcohol.[31] In a 2009 interview, the founder of the sect, Mohammed Yusuf, asserted his belief that the theory that the Earth is round is contrary to Islamic teaching and should be rejected.[34] According to Borno Sufi Imam Sheik Fatahi, Yusuf was trained by Kano Salafi Izala Sheik Ja'afar Mahmud Adamu, who called him the "leader of young people"; the two split some time in 2002-4. They both preached in Maiduguri's Indimi Mosque, which was attended by the deputy governor of Borno.[16][35] Many of the group were reportedly inspired by Mohammed Marwa, known as Maitatsine ('He who curses others'), a self-proclaimed prophet (annabi, a Hausa word usually used only to describe the founder of Islam), born in Northern Cameroon, who condemned the reading of books other than the Quran.[36][37][38][39]

Boko Haram conducted its operations more or less peacefully during the first seven years of its existence, withdrawing from society into remote north-eastern areas. The government repeatedly ignored warnings about the increasingly militant character of the organization.[21][40] In 2009 police began an investigation into the group code-named 'Operation Flush'. On 26 July, security forces arrested nine Boko Haram members and confiscated weapons and bomb-making equipment. Either this, or a clash with police during a funeral procession, led to revenge attacks on police and widespread rioting. A Joint Military Task Force operation was launched in response, and by 30 July more than 700 people had been killed, mostly Boko Haram members, and police stations, prisons, government offices, schools and churches had been destroyed.[7][18]: 98–102 [41][42] Yusuf was arrested, and died in custody "while trying to escape". He was succeeded as leader by Abubakar Shekau, formerly his second-in-command.[43][44] A classified cable sent from the US Embassy in Abuja in November 2009, available on WikiLeaks, is illuminating:[16]

"[Borno political and religious leaders] ...asserted that the state and federal government responded appropriately and, apart from the opposition party, overwhelmingly supported Yusuf's death without misgivings over the extrajudicial killing. Security remained a concern in Borno, with residents expressing concern about importation of arms and exchanges of religious messages across porous international borders. The government has proposed a preaching board which will certify Muslim preachers, but it has not yet been inaugurated. While most contacts described Borno as a "State of Peace" and did not expect additional attacks, the Northeast remained vulnerable to violence and extremist attacks due to lack of employment opportunities for youth, exasperated by ethnic and religious tensions."

Campaign of violence

Government officials were aware of arms shipments coming into Borno, and audio tapes were believed to be in circulation in which Yusuf's deputy threatened future attacks. However, many observers did not anticipate imminent bloodshed. Security in Borno was downgraded. Borno government official Alhaji Boguma believed that the state deserved praise from the international community for ending the conflict in such a short time, and that the "wave of fundamentalism has been crushed."[16] In September 2010, having regrouped under their new leader, Boko Haram broke 105 of its members out of prison in Maiduguri along with over 600 other prisoners and went on to launch attacks in several areas of northern Nigeria. As had been the case decades earlier in the wake of the 1980 Kano riots, the government's reliance on a purely military strategy, once again executing the leader of a militant group, would have unintended consequences.[11][45][46]

Under Shekau's leadership, the group continuously improved its operational capabilities. After launching a string of IED attacks against soft targets, and its first vehicle-borne IED attack in June 2011, killing 6 at the Abuja police HQ, in August Boko Haram bombed the UN HQ in Abuja, the first time they had struck a Western target. A spokesman claiming responsibility for the attack, in which 11 UN staff members died as well as 12 others with more than 100 injured, warned of future planned attacks on US and Nigerian government interests. Speaking soon after the US embassy's announcement of the arrival in the country of the FBI, he went on to announce Boko Haram's terms for negotiation: the release of all imprisoned members. The increased sophistication of the group led observers to speculate that Boko Haram was affiliated with AQIM, which was known to be active in Niger.[45][46][47][48][49][50]

Boko Haram have maintained a steady rate of attacks since 2011, striking a wide range of targets, multiple times per week. They have attacked politicians, religious leaders, security forces and civilian targets. The tactic of suicide bombing, used in the two attacks in the capital on the police and UN HQs, was new to Nigeria, and alien to its mercenary culture. In Africa as a whole, it had only been used by al-Shabab in Somalia and, to a lesser extent, AQIM. Since early 2013 Boko Haram have increasingly operated in Northern Cameroon, and have been involved in skirmishes along the borders of Chad and Niger. They have been linked to a number of kidnappings, often reportedly in association with the splinter group Ansaru, drawing them a higher level of international attention.[48][51][52][53][7][2]

Inauguration

Within hours of Goodluck Jonathan's presidential inauguration in May 2011, Boko Haram carried out a series of bombings in Bauchi, Zaria and Abuja. The most successful of these was the attack on the army barracks in Bauchi. A spokesman for the group told BBC Hausa that the attack had been carried out, as a test of loyalty, by serving members of the military hoping to join the group. This charge was later refuted by an army spokesman, who claimed, "This is not a banana republic". However, on 8 January 2012 the President would announce that Boko Haram had in reality infiltrated both the army and the police, as well as the executive, parliamentary and legislative branches of government. Boko Haram's spokesman also claimed responsibility for the killing outside his home in Maiduguri of the politician Abba Anas Ibn Umar Garbai, the younger brother of the Shehu of Borno, who was the second most prominent Muslim in the country after the Sultan of Sokoto. He added, “We are doing what we are doing to fight injustice, if they stop their satanic ways of doing things and the injustices, we would stop what we are doing.”[54][55]

This was one of several political and religious assassinations Boko Haram carried out that year, with the presumed intention of correcting injustices in the group's home state of Borno. Meanwhile, the trail of massacres continued relentlessly, apparently leading the country towards civil war. By the end of 2011, these conflicting strategies led observers to question the group's cohesion; comparisons were drawn with the diverse motivations of the militant factions of the oil-rich Niger Delta. In November, the State Security Service announced that four criminal syndicates were operating under the name 'Boko Haram'.[51][56][57][58]

The common theme throughout the northeast was the targeting of police, who were regularly massacred at work or in drive-by shootings at their homes, either in revenge for the killing of Yusuf, or as representatives of an illegitimate state apparatus or for no particular reason. Five officers were arrested for Yusuf's murder, which had no noticeable effect on the level of unrest. Opportunities for criminal enterprise flourished. Hundreds of police were dead and more than 60 police stations had been attacked by mid 2012. The government's response to this self-reinforcing trend towards insecurity was not to restructure or reorientate the security services, but rather to invest heavily in security equipment, spending $5.5 billion, 20% of their overall budget, on bomb detection units, communications and transport; and $470 million on a Chinese CCTV system for Abuja, which has failed in its purpose of detecting or deterring acts of terror.[57][59][60][61][62][63]

The election defeat of former military dictator Muhammadu Buhari had raised religious political tension, as it broke the terms of a tacit agreement whereby, after two terms, the presidency was expected to change hands to a northern, Muslim candidate, thus distributing the country's oil wealth more fairly, through the customary corrupt channels. The subsequent campaign of violence by Boko Haram culminated in a string of bombings across the country on Christmas Day. In the outskirts of Abuja, 37 died in a church which had its roof blown off. "Cars were in flames and bodies littered everywhere," one resident commented, words that were to be repeated in nearly all press reports, which speedily delivered information about the aftermath of the bombings around the globe. Similar Christmas events had occurred in previous years. Jonathan declared a state of emergency on New Year's Eve in local government areas of Jos, Borno, Yobe, and Niger, and closed the international border in the northeast. On the next day, he announced that he was scrapping fuel subsidies. The IMF had recommended the move, but Nigerians believed that the savings of $8 billion a year would be stolen. Fuel prices quickly doubled, leading to widespread strikes and protests which were quelled a fortnight later, with army checkpoints throughout the commercial capital Lagos and police firing live ammunition and teargas.[64][65][66][67][68][69][70][71]

State of emergency

Boko Haram had carried out 115 attacks in 2011, killing 550. The state of emergency would usher in an intensification of violence. The opening three weeks of 2012 accounted for more than half of the death total of the preceding year. Two days after the state of emergency was declared, Boko Haram released an ultimatum to southern Nigerians living in the north, giving them three days to leave. Three days later they began a series of mostly small-scale attacks on Christians and members of the Igbo ethnic group, causing hundreds to flee. In Kano, on 20 January, they carried out by far their most deadly action yet, an assault on police buildings, killing 190. One of the victims was a TV reporter; information is limited. The attacks included a combined use of car bombs, suicide bombers and IEDs, supported by uniformed gunmen.[4][72][73][74][75][76][77]

Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch published reports in 2012 which were widely quoted by government agencies and the media, based on research conducted over the course of the conflict in the worst affected areas of the country. The NGOs were critical of both security forces and Boko Haram. HRW stated "Boko Haram should immediately cease all attacks, and threats of attacks, that cause loss of life, injury, and destruction of property. The Nigerian government should take urgent measures to address the human rights abuses that have helped fuel the violent militancy." According to the 2012 US Department of State Country Report on Human Rights Practices,[9]

"...serious human rights problems included extrajudicial killings by security forces, including summary executions; security force torture, rape, and other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment of prisoners, detainees, and criminal suspects; harsh and life-threatening prison and detention center conditions; arbitrary arrest and detention; prolonged pretrial detention; denial of fair public trial; executive influence on the judiciary; infringements on citizens’ privacy rights; restrictions on freedom of speech, press, assembly, religion, and movement..."

"On October 9, witnesses in Maiduguri claimed members of the JTF “Restore Order,” [a vigilante group] based in Maiduguri, went on a killing spree after a suspected Boko Haram bomb killed an officer. Media reported the JTF killed 20 to 45 civilians and razed 50 to 100 houses in the neighborhood. The JTF commander in Maiduguri denied the allegations. On November 2, witnesses claimed the JTF shot and killed up to 40 people during raids in Maiduguri. The army claimed it dismissed some officers from the military as a result of alleged abuses committed in Maiduguri, but there were no known formal prosecutions in Maiduguri by year’s end."

"Credible reports also indicated... uniformed military personnel and paramilitary mobile police carried out summary executions, assaults, torture, and other abuses throughout Bauchi, Borno, Kano, Kaduna, Plateau, and Yobe states... The national police, army, and other security forces committed extrajudicial killings and used lethal and excessive force to apprehend criminals and suspects, as well as to disperse protesters. Authorities generally did not hold police accountable for the use of excessive or deadly force or for the deaths of persons in custody. Security forces generally operated with impunity in the illegal apprehension, detention, and sometimes extrajudicial execution of criminal suspects. The reports of state or federal panels of inquiry investigating suspicious deaths remained unpublished."

"There were no new developments in the case of five police officers accused of executing Muhammad Yusuf in 2009 at a state police headquarters. In July 2011 authorities arraigned five police officers in the federal high court in Abuja for the murder of Yusuf. The court granted bail to four of the officers, while one remained in custody."

"Police use of excessive force, including use of live ammunition, to disperse demonstrators resulted in numerous killings during the year. For example, although the January fuel subsidy demonstrations generally remained peaceful, security forces reportedly fired on protesters in various states across the country during those demonstrations, resulting in 10 to 15 deaths and an unknown number of wounded."

"Despite some improvements resulting from the closure of police checkpoints in many parts of the country, states with an increased security presence due to the activities of Boko Haram experienced a rise in violence and lethal force at police and military roadblocks."

"Continuing abductions of civilians by criminal groups occurred in the Niger Delta and Southeast... Police and other security forces were often implicated in the kidnapping schemes."

"Although the constitution and law prohibit such practices and provide for punishment of such abuses, torture is not criminalized, and security service personnel, including police, military, and State Security Service (SSS) officers, regularly tortured, beat, and abused demonstrators, criminal suspects, detainees, and convicted prisoners. Police mistreated civilians to extort money. The law prohibits the introduction into trials of evidence and confessions obtained through torture; however, police often used torture to extract confessions."[78]

In late 2013 AI received 'credible' information that over 950 inmates had died in custody, mostly in detention centres in Maiduguri and Damaturu, within the first half of the year. Official state corruption was also documented in December 2013 by the UK Home Office:[79][80]

"The NPF, SSS, and military report to civilian authorities; however, these security services periodically act outside of civilian control. The government lack effective mechanisms to investigate and punish abuse and corruption. The NPF remain susceptible to corruption, commit human rights abuses, and generally operate with impunity in the apprehension, illegal detention, and sometimes execution of criminal suspects. The SSS also commit human rights abuses, particularly in restricting freedom of speech and press. In some cases private citizens or the government brought charges against perpetrators of human rights abuses in these units. However, most cases lingered in court or went unresolved after an initial investigation."

State of emergency extended

In April 2014, Boko Haram kidnapped 276 female students from Chibok, Borno. More than 50 of them soon escaped, but the remainder have not been released. Instead Shekau, who has a reward of $7 million offered by the US DOS since June 2013 for information leading to his capture, announced his intention of selling them into slavery. The incident brought Boko Haram extended global media attention, much of it focused on the pronouncements of the US First Lady. Faced with outspoken condemnation for his perceived incompetence, and detailed accusations from AI of state collusion, Jonathan famously responded by hiring a Washington PR firm.[81][82][83][84][85][86][87][88]

The state of emergency was extended in May 2013 to cover the whole of the three northeastern states of Borno, Adamawa and Yobe, raising tensions in the region. In the 12 months following the announcement, 250,000 fled the three states, followed by a further 180,000 between May and August 2014. 210,000 fled from bordering states, bringing the total displaced by the conflict to 650,000. Many thousands left the country. An August 2014 AI video showed army and allied militia executing people, including by slitting their throats, and dumping their bodies in mass graves.[89][90][91]

The US Bureau of Counterterrorism provides the following summary of Boko Haram's 2013 foreign operations:

In February 2013, Boko Haram was responsible for kidnapping seven French tourists in the far north of Cameroon. In November 2013, Boko Haram members kidnapped a French priest in Cameroon. In December 2013, Boko Haram gunmen reportedly attacked civilians in several areas of northern Cameroon. Security forces from Chad and Niger also reportedly partook in skirmishes against suspected Boko Haram members along Nigeria’s borders. In 2013, the group also kidnapped eight French citizens in northern Cameroon and obtained ransom payments for their release.[2]

Boko Haram has often managed to evade the Nigerian army by retreating into the hills around the border with Cameroon, whose army is apparently unwilling to confront them. Nigeria, Chad and Niger had formed a Multinational Joint Task Force in 1998. In February 2012, Cameroon signed an agreement with Nigeria to establish a Joint Trans-Border Security Committee, which was inaugurated in November 2013, when Cameroon announced plans to conduct "coordinated but separate" border patrols in 2014. It convened again in July 2014 to improve cooperation between the two countries.[92][93][94][95][96]

In 2014 Boko Haram continued to increase its presence in northern Cameroon. In May, ten Chinese workers were abducted. In July the Vice-President's home village was attacked by around 200 militants; his wife was kidnapped, along with the Sultan of Kolofata and his family. At least 15 people, including soldiers and police, were killed in the raid. In a separate attack, nine bus passengers and a soldier were shot dead and the son of a local chief was kidnapped. Hundreds of young locals are suspected to have been recruited. In August, the remote Nigerian border town of Gwoza was overrun and held by the group. In response to the increased militant activity, the Cameroonian President sacked two senior military officers and sent his army chief with 1000 reinforcements to the northern border area.[97][98][99]

Between May and July, 8,000 Nigerian refugees arrived in the country, up to 25% suffering from acute malnutrition. Cameroon, which ranked 150 out of 186 on the 2012 UNDP HDI, currently (August 2014) hosts 107,000 refugees fleeing unrest in the CAR, expected to increase to 180,000 by the end of the year. In 2013, a minister at the far north governor’s office stated, “We do not have the resources to monitor all the borders.”[100][101][102]

Timeline of Boko Haram attacks

Between 2009 and beginning of 2012, Boko Haram was responsible for over 900 deaths.[103]

On 14 May 2013, President Goodluck Jonathan declared a state of emergency in the states of Borno, Yobe, and Adamawa in a bid to fight the activities of Boko Harām. He ordered the Nigerian Armed Forces to the three areas around Lake Chad.[104] As of 17 May, Nigerian armed forces' shelling in Borno resulted in at least 21 deaths.[105] A curfew was imposed in Maiduguri as the military used air strikes and shellings to target Boko Harām strongholds.[106] The Nigerian state imposed a blockade on the group's traditional base of Maiduguri in Borno in order to re-establish Nigeria's "territorial integrity".[107]

On 21 May, the Defence Ministry issued a statement that read it had "secured the environs of New Marte, Hausari, Krenoa, Wulgo and Chikun Ngulalo after destroying all the terrorists' camps". Armed Forces Spokesman in Borno Lieutenant Colonel Sagir Musa said that the curfew that had been imposed was not relaxed with the curfew timings being 18:00 to 7:00, however there was minimal traffic in Maiduguri.[108]

On 29 May, Boko Haram's leader Abubakar Shekau, following military claims that the group had been halted,[109] released a video in which he said the group had not lost to the Nigerian armed forces. In the video he showed charred military vehicles and bodies dressed in military fatigues. While he called on Muslims from Iraq, Pakistan, Afghanistan and Syria to join his jihad, he said in Arabic and Hausa:[110]

My fellow brethren from all over the world, I assure you that we are strong, hale and hearty since they launched this assault on us following the state of emergency declaration. When they launch any attack on us you see soldiers fleeing and throwing away their weapons like a rabbit that is been hunted down.

On the same day, Nigeria's Director of Defence Information Brigadier-General Chris Olukolade said that Shekau's unnamed deputy was found dead near Lake Chad and that two others from Boko Haram were arrested in the area. However, the military's claims were not verified.[111]

Satellite photos raise questions about the government's retaliatory attack on Boko Haram on April 16–17, 2013. Over 180 died, mostly from fires that appeared to be deliberately set during the government attack. Boko Haram fighters and civilians died in the attack.[112][113] The people of Maiduguri were unhappy with the declaration of war on the group and instead said the issues of poverty and inequality needed to be tackled first.[114]

It was reported in August 2013 that Shekau had been shot and deposed by members of his sect,[115] but he survived. He had been described as "the most dreaded and wanted" Boko Harām leader and the United States had recently offered a US$7m bounty for information leading to his arrest.[116] He has taken responsibility for the April 2014 kidnapping of over 200 school girls.[117] On 6 May 2014, eight more girls were kidnapped by suspected Boko Harām gunmen.[118][119] In a videotape, Shekau threatened to sell the kidnapped girls into slavery.[120] On May 12, 2014 Boko Haram released a video which shows the kidnapped girls and alleging that the girls had converted to Islam and would not be released until all militant prisoners were freed.[121] On May 17, 2014, Nigerian President Goodluck Jonathan and the presidents of Benin, Chad, Cameroon and Niger met in Paris and agreed to combat Boko Haram on a coordinated basis, sharing in particular surveillance and intelligence gathering. Chad President Idriss Deby said after the meeting African nations were determined to launch a total war on Boko Haram. Westen nations, including Britain, France, Israel, and the United States had also pledged support.[122][123]

On 22 May 2014 Boko Haram was officially declared a terrorist group affiliated to Al-Qaeda and Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb by the United Nations Security Council.[124] International sanctions including asset freeze, travel ban and arms embargo were imposed against the Islamist extremist group.[125]

On May 2014, Nigerian soldiers shot at the car of their divisional commander whom they suspected of colluding with Boko Haram and it was reported that nine Nigerian generals were being investigated for suspected sale of weapons to Boko Haram.[126]

Amnesty International accused the Nigerian government of human rights abuses after 950 suspected Boko Haram militants died in detention facilities run by Nigeria's military Joint Task Force in the first half of 2013.[127]

On 11 August 2014, Boko Haram militants raided villages in Borno State in the northeast of Nigeria, killing 28 and kidnapping a further 97. Scores of homes were set on fire.Boko Haram have said to be taken over Gwoza town[128]

Name

The official name is جماعة أهل السنة للدعوة والجهاد Jama'atu Ahlis Sunna Lidda'Awati Wal-Jihad, a.k.a. Jama'atu Ahlus-Sunnah Lidda'Awati Wal Jihad, in an orientalist scholars' romanisation jamāʿtu ʾahli 's-sunnati li-d-daʿwati wa-l-jihād, meaning in a word by word translation "People Committed to the Prophet's Teachings for Propagation and Jihad."[129] Since "Ahlus-Sunnah" ist the common word for adherents to Sunni Islam and Daʿwa(ti) for proselytizing or preaching of Islam, it means "Association of Sunnis for Proselytizing (of Islam) and Jihad".

The group was originally also known as 'Yusifiyya', after its leader, Mohammed Yusuf, until his death in 2009.[16] The name 'Boko Haram', 'Western education is forbidden', is from the Arabic حَرَام ḥarām, 'forbidden'; and the Hausa word boko [the first vowel is long, the second pronounced in a low tone], 'fake' (defined as "(a) Doing anything to create impression that one is better off, or that thing is of better quality or larger in amount than is the case, (b) anything so treated... etc.")[39][130]

Western education has always been dismissed as ilimin boko; a school that teaches Western education is makaranta boko. The uncompromising hostility of the northern Nigerian Muslims towards anything remotely perceived as foreign, a mindset of boko haram that has in the past been applied even towards vocal recitation of the Quran, has historically been a source of friction with the Muslims from the middle of the country.[39][130][131]

Boko Haram has also been translated as "non-Moslem education is forbidden,"[132][133] “Western influence is a sin,”[134] and “Westernization is sacrilege."[7]

Assessment

The US State Department designated Boko Haram and Ansaru as terrorist organisations in November 2013, citing various reasons including links with AQIM, "thousands of deaths in northeast and central Nigeria over the last several years, including targeted killings of civilians", and Ansaru's 2013 kidnapping and execution of seven international construction workers. In the statement from the Department it was noted, however, "These designations are an important and appropriate step, but only one tool in what must be a comprehensive approach by the Nigerian government to counter these groups through a combination of law enforcement, political, and development efforts (sic)."[3] The State Department had resisted earlier calls to designate the group, after the 2011 UN bombing.[136] Boko Haram is not currently (June 2014) believed by the US government to be affiliated to al Qaeda.[4]

Boko Haram gets funding from bank robberies and kidnapping ransoms.[73][137] In February 2012, recently arrested officials revealed that while the organization initially relied on donations from members, its links with AQIM opened it up to funding from groups in Saudi Arabia and the UK.[138][139] The group also extorts local governments. A spokesman of Boko Haram claimed that Kano state governor Ibrahim Shekarau and Bauchi state governor Isa Yuguda had paid them monthly.[140][141] In the past, Nigerian officials have been criticized for being unable to trace much of the funding that Boko Haram has received.[142] James Cockayne, formerly Co-Director of the Center on Global Counterterrorism Cooperation and Senior Fellow at the International Peace Institute, wrote in 2012,[143][144]

"Given their appreciation of the contested nature of much African governance, it comes as something of a surprise that Carrier and Klantschnig [Review of Africa and the War on Drugs, 2012] fiercely downplay the impact that cocaine trafficking is having on West African governance. On the basis of just three case studies (Guinea-Bissau, Lesotho and Nigeria) the authors conclude that ‘state complicity’ in the African drug trade is ‘rare’, and the dominant paradigm is ‘repression’. As a result, they radically understate the close involvement of political and military actors in drug trafficking – particularly in West African cocaine trafficking – and overlook the growing power of drug money in African electoral politics, local and traditional governance, and security."

The Nigerian military is, in the words of a former British military attaché speaking in 2014, "a shadow of what it's reputed to have once been. It's fallen apart." They are short of basic equipment, including radios and armoured vehicles. Morale is said to be low. The country's defense budget accounts for more than a third of the security budget of $5.8 billion, but only 10% is allocated to capital spending.[145] In a 2014 US DOD assessment, funds are being "skimmed off the top", troops are “showing signs of real fear,” and are “afraid to even engage.”[4]: 9

In July 2014, Nigeria was estimated to have had the highest number of terrorist killings in the world over the past year, 3477, killed in 146 attacks.[146] The governor of Borno, Kashim Shettima, of the opposition ANPP, said in 2014:[147]

"Boko Haram are better armed and are better motivated than our own troops. Given the present state of affairs, it is absolutely impossible for us to defeat Boko Haram."

See also

References

- ^ "Al-Qaeda map: Isis, Boko Haram and other affiliates' strongholds across Africa and Asia". 12 June 2014. Retrieved 1 September 2014., see interactive infographic

- ^ a b c Bureau of Counterterrorism. "Country Reports on Terrorism 2013". US Department of State. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ^ a b Office of the Spokesperson (13 November 2013). "Terrorist Designations of Boko Haram and Ansaru". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 24 July 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f Lauren Ploch Blanchard (10 June 2014). "Nigeria's Boko Haram: Frequently Asked Questions" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. Retrieved 3 August 2014.

- ^ 19 July 2014 (19 July 2014). "Boko Haram insurgents kill 100 people as they take control of Nigerian town". Guardian. Retrieved 20 July 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Africa Program at the Council on Foreign Relations (2014). "Nigeria Security Tracker". www.cfr.org. Council of Foreign Relations. Retrieved 21 July 2014.

- ^ a b c d "Boko Haram". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved September 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Glenn Kessler (19 May 2014). "Boko Haram: Inside the State Department debate over the 'terrorist' label". Washington Post. Retrieved 3 August 2014.

- ^ a b "Nigeria: Boko Haram Attacks Likely Crimes Against Humanity". Human Rights Watch. 11 October 2012. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- ^ "Islamists force 650 000 Nigerians from homes". News 24. 5 August 2014. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- ^ a b Martin Ewi (24 June 2013). "Why Nigeria needs a criminal tribunal and not amnesty for Boko Haram". Institute for Security Studies. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- ^ Johnson, Toni (31 August 2011). "Backgrounder: Boko Haram". Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ Chothia, Farouk (11 January 2012). "Who are Nigeria's Boko Haram Islamists?". BBC News. Retrieved 25 January 2012.

- ^ "Analysis: Understanding Nigeria's Boko Haram radicals". www.irinnews.org. IRIN. 18 July 2011. Retrieved 12 March 2012.

- ^ "Whose faith, whose girls?". The Economist.

- ^ a b c d e f US Embassy, Abuja (November 4, 2009). "Nigeria: Borno State Residents Not Yet Recovered From Boko Haram Violence". Wikileaks. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Chris Kwaja (July 2011). "Nigeria's Pernicious Drivers of Ethno-Religious Conflict" (PDF). Africa Security Brief (14). Africa Center for Strategic Studies. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2013.

- ^ a b c Adesoji, Abimbola (2010). "The Boko Haram Uprising and Islamic Revivalism in Nigeria". Africa Spectrum. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Zango-Kataf Riots in Nigeria 1992". Armed Conflicts Events Database. December 16, 2000. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Kirk Ross (May 19, 2014). "Revolt in the North: Interpreting Boko Haram's war on western education". African Arduments. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b Cook, David (26 September 2011). "The Rise of Boko Haram in Nigeria". Combating Terrorism Centre. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- ^ http://www.scarrdc.org/uploads/2/6/5/4/26549924/bederkawahhabism.pdf

- ^ http://www.gloria-center.org/2014/07/the-diffusion-of-intra-islamic-violence-and-terrorism-the-impact-of-the-proliferation-of-salafiwahhabi-ideologies/

- ^ http://sunnicity.com/2013/08/14/boko-haram-killed-muslims-in-mosque/

- ^ Onuoha, Freedom (2014). "Boko Haram and the evolving Salafi Jihadist threat in Nigeria". In de Montclos, Pérouse (ed.). Boko Haram: Islamism, politics, security and the state in Nigeria (PDF). Leiden: African Studies Centre. p. 158. ISBN 978-90-5448-135-5. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ^ "African Arguments Editorial – Boko Haram in Nigeria : another consequence of unequal development". African Arguments. 9 November 2011. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- ^ Bartolotta, Christopher (23 September 2011). "Terrorism in Nigeria: the Rise of Boko Haram". The Whitehead Journal of Diplomacy and International Relations. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- ^ Zainab Usman (May 1, 2014). "Nigeria's Economic Transition Reveals Deep Structural Distortions". African Arguments. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Data". The World Bank. Retrieved 3 August 2014.

- ^ "Nigerians living in poverty rise to nearly 61%". BBC. 13 February 2012. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b "USCIRF Annual Report 2013 - Thematic Issues: Severe religious freedom violations by non-state actors". UNHCR. 30 April 2013. Retrieved 3 August 2014.

- ^ Barnaby Phillips (20 January 2000). "Islamic law raises tension in Nigeria". BBC. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ^ "Article 7: Right to equal protection by the law". BBC World Service. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ^ "Nigeria's 'Taliban' enigma". BBC News. 28 July 2009. Retrieved 28 July 2009.

- ^ Gérard L. F. Chouin, Religion and bodycount in the Boko Haram crisis: evidence from the Nigeria Watch database, p. 214. ISBN 978-90-5448-135-5

- ^ a b Adebayo, Akanmu G (2012), Managing Conflicts in Africa's Democratic Transitions, p. 176

- ^ West African Studies Conflict over Resources and Terrorism, OECD, 2013

- ^ J. Peter Pham (19 Oct 06). "In Nigeria False Prophets Are Real Problems". World Defense Review. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ a b c George Percy Bargery (1934). "Hausa-English dictionary". Lexilogos. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- ^ "Nigeria accused of ignoring sect warnings before wave of killings". The Guardian. London. 2 August 2009. Retrieved 6 August 2009.

- ^ Joe Bavier (15 January 2012). "Nigeria: Boko Haram 101". Pulitzercenter.org.

- ^ Nossiter, Adam (27 July 2009). "Scores Die as Fighters Battle Nigerian Police". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 January 2012.

- ^ "Nigeria sect head dies in custody". BBC. 31 July 2009. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- ^ "Nigeria killings caught on video – Africa". Al Jazeera English.

- ^ a b "Boko Haram attacks – timeline". The Guardian. 25 September 2012. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- ^ a b "Peace and Security Council Report" (PDF). ISS. February 2012. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- ^ Ndahi Marama (30 July 2014). "UN House bombing: Why we struck-Boko Haram". Vanguard. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- ^ a b "Counterterrorism 2014 Calendar". The National Counterterrorism Center. 2014. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- ^ IBRAHIM MSHELIZZA (29 August 2011). "Islamist sect Boko Haram claims Nigerian U.N. bombing". Reuters. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- ^ JOE BROCK (31 January 2012). "Special Report: Boko Haram - between rebellion and jihad". Reuters. Retrieved 3 August 2014.

- ^ a b Richard Dowden (9 March 2012). "Boko Haram – More Complicated Than You Think". Africa Arguments. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- ^ David Cook (26 September 2011). "THE RISE OF BOKO HARAM IN NIGERIA". Combating Terrorism Center. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- ^ "Boko Haram attacks an air base in Nigeria". Aljazeera. 3 December 2013. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- ^ "Boko Haram claims responsibility for bomb blasts in Bauchi, Maiduguri - See more at: http://www.vanguardngr.com/2011/06/boko-haram-claims-responsibility-for-bomb-blasts-in-bauchi-maiduguri/#sthash.9I9F0vFy.dpuf". Vanguard News. 1 June 2011. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

{{cite web}}: External link in|title= - ^ OLALEKAN ADETAYO (9 January 2012). "Boko Haram has infiltrated my govt –Jonathan". Punch. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- ^ David Cook (26 September 2011). "THE RISE OF BOKO HARAM IN NIGERIA". Combating Terrorism Center. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- ^ a b JEAN HERSKOVITS (2 January 2012). "In Nigeria, Boko Haram Is Not the Problem". New York Times. Retrieved 3 August 2014.

- ^ Olly Owen (19 January 2012). "Boko Haram: Answering Terror With More Meaningful Human Security". African Arguments. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- ^ Olly Owen (19 January 2012). "Boko Haram: Answering Terror With More Meaningful Human Security". African Arguments. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- ^ Gernot Klantschnig (February 2012). "Review of the January 2012 UK Border Information Service Nigeria Country of Origin Information Report" (PDF). Independent Advisory Group on Country Information. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- ^ Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor. "Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 2012". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 4 August 2014.

- ^ "Nigeria: Boko Haram Attacks Likely Crimes Against Humanity". Human Rights Watch. 11 October 2012. Retrieved 4 August 2014.

- ^ Ibanga Isine (June 27, 2014). "High-level corruption rocks $470million CCTV project that could secure Abuja". Premium Times. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Duncan Gardham, Laura Heaton (25 December 2011). "Coordinated bomb attacks across Nigeria kill at least 40". The Telegraph. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Five bombs explode across Nigeria killing dozens". Buenos Aires Herald. December 25, 2011. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ ADAM NOSSITER (December 25, 2011). "Nigerian Group Escalates Violence With Church Attacks". New York Times. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ TINA MOORE (December 25, 2011). "Christmas Day bombings in Nigeria kill at least 39, radical Muslim sect claims responsibility". New York Daily News. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Nigeria churches hit by blasts". Aljazeera. 26 Dec 2011. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Christmas bombings kill many near Jos, Nigeria". BBC. 25 December 2010. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Felix Onuah and Tim Cocks (31 December 2011). "Nigeria's Jonathan declares state of emergency". Reuters. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- ^ "Nigerian fuel subsidy: Strike suspended". BBC. 16 January 2012. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- ^ David Blair (5 February 2012). "Al-Qaeda's hand in Boko Haram's deadly Nigerian attacks". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 3 August 2014.

- ^ a b MIKE OBOH (22 January 2012). "Islamist insurgents kill over 178 in Nigeria's Kano". Reuters. Retrieved 3 August 2014.

- ^ Associated Press (23 January 2012). "Nigerians offer prayers in Kano for suicide bombers' victims". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 August 2014.

- ^ "Nigeria's Kano rocked by multiple explosions". BBC. 21 January 2012. Retrieved 3 August 2014.

- ^ Taye Obateru & Grateful Dakat (22 January 2012). "Boko Haram: Fleeing Yobe Christians". Vanguard. Retrieved 3 August 2014.

- ^ "Nigeria: Boko Haram Widens Terror Campaign". Human Rights Watch. 24 January 2012. Retrieved 2 August 2014.

- ^ Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor (2012). "Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 2012". US Department of State. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ^ "Nigeria: Deaths of hundreds of Boko Haram suspects in custody requires investigation". Amnesty International. 15 October 2013. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ^ December 2013. "Operational Guidance Note" (PDF). Home Office. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Rewards for Justice - First Reward Offers for Terrorists in West Africa". U.S. Department of State. 3 June 2013.

- ^ "Nigeria says 219 girls in Boko Haram kidnapping still missing". Fox News. June 23, 2014. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ MARIA TADEO (10 May 2014). "Nigeria kidnapped schoolgirls: Michelle Obama condemns abduction in Mother's Day presidential address". The Independent. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Tim Cocks (July 8, 2014). "Jonathan's PR offensive backfires in Nigeria and abroad". Yahoo! News/Reuters. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Megan R. Wilson (2014-06-26). "Nigeria hires PR for Boko Haram fallout". The Hill. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Nigeria: Government knew of planned Boko Haram kidnapping but failed to act". Amnesty International UK. 9 May 2014. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Taiwo Ogunmola Omilani (Jul 24, 2014). "Chibok Abduction: NANS Describes Jonathan As Incompetent". Leadership, Nigeria. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "One month after Chibok girls' abduction". The Nation, Nigeria. May 15, 2014. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "650,000 Nigerians Displaced Following Boko Haram Attacks – UN". Information Nigeria. 5 August 2014. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ^ Adrian Edwards (9 May 2014). "Refugees fleeing attacks in north eastern Nigeria, UNHCR watching for new displacement". UNHCR. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ^ Emele Onu (Aug 5, 2014). "Amnesty Says 'Gruesome' Nigerian Footage Shows War Crimes". Bloomberg. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "With cross-border attacks, Boko Haram threat widens". IRIN. 21 November 2013. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ^ Tim Cocks (30 May 2014). "Cameroon weakest link in fight against Boko Haram". Reuters. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ^ "Nigeria: FG Inaugurates Nigeria-Cameroon Trans-Border Security Committee". allAfrica. 5 February 2013. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "2nd session of Nigeria/Cameroon Trans-Border Security Committee meets in Abuja". Daily Independent. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Nigeria-Cameroon security committee meets". News 24 Nigeria. 2014-07-07. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Boko Haram plans more attacks, recruits many young people - See more at: http://www.vanguardngr.com/2014/08/boko-haram-plans-attacks-recruits-many-young-people/#sthash.iH57fjGc.dpuf". Vanguard. 8 August 2014. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

{{cite web}}: External link in|title= - ^ "'Islamist militants' kill 10 in northern Cameroon". BBC. 6 August 2014. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ^ HARUNA UMAR (August 7, 2014). "Boko Haram takes Nigeria town, resident says". Yahoo! News. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Cameroon receives 8,000 refugees fleeing Boko Haram in Nigeria". Nigerian Tribune. 13 Jul 2014. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Cameroon: Malnutrition Hits Children Arriving From Central African Republic". World Food Program. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Nigerian overnight refugees worry Cameroon". IRIN. 24 December 2013. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Nossiter, Adam (25 February 2012). "In Nigeria, a Deadly Group's Rage Has Local Roots". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 February 2012.

- ^ "'Massive' troop deployment in Nigeria – Africa". English. Al Jazeera. 15 May 2013. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- ^ "Nigerian forces 'shell fighter camps' – Africa". English. Al Jazeera. 17 May 2013. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- ^ "Nigeria sets curfew in Boko Haram stronghold – Africa". English. Al Jazeera. 18 May 2013. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- ^ "Nigerian army blockades Boko Haram base". English. Al Jazeera. 19 May 2013. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- ^ "Nigeria eases curfew in northeast". English. Al Jazeera. May 2013. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- ^ Ross, Will (20 May 2013). "Nigeria: Boko Haram in disarray, says army". BBC News. BBC. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- ^ Abrak, Isaac (29 May 2013). "Boko Haram rebels say Nigerian military offensive is failing". Reuters. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- ^ "Boko Haram leader Shekau's associate found dead, says Defence Hqtrs". The Nation. 29 May 2013. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- ^ "What is Boko Haram?". The Economist. 1 May 2013.

- ^ "Nigeria: Massive Destruction, Deaths From Military Raid". Human Rights Watch. 1 May 2013.

- ^ Parker, Gillian (28 May 2013). "In Boko Haram country, Nigeria's new crackdown brings mixed feelings". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- ^ "Abubakar Shekau of Nigeria's Boko Haram may be dead". News Africa. BBC. 19 August 2013.

- ^ "Nigeria claims Boko Haram chief may be dead". Al Jazeera. 20 August 2013.

Army claims the 'most dreaded and wanted' leader may have died after being shot in a battle in the last few weeks.

- ^ Terrence McCoy (6 May 2014). "The man behind the Nigerian girls' kidnappings and his death-defying mystique". Washington Post.

- ^ "Police: Suspected Boko Haram Gunmen Kidnap 8 More Girls In Northeast Nigeria". The Huffington Post. Reuters. 6 May 2014.

- ^ Tharoor, Ishaan (5 May 2014). "8 questions you want answered about Nigeria's missing schoolgirls". The Washington Post.

- ^ "Nigeria group threatens to sell kidnapped girls". The Washington Post. AP. 5 May 2015.

- ^ Lanre Ola (12 May 2014). "Boko Haram offers to swap kidnapped Nigerian girls for prisoners". Reuters.

- ^ "Boko Haram to be fought on all sides". Nigerian News.Net. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Boko Haram and the Future of Nigeria, by Dr. Jacques Neriah Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs

- ^ "UN blacklists Nigeria's Boko Haram". Aljazeera. 23 May 2014. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- ^ "US Says UN Approves Sanctions on Boko Haram". English. ABC News. 22 May 2014. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- ^ Grill, Bartholomaus and Selander, Toby (30 May 2014) The Devil in Nigeria: Boko Haram's Reign of Terror Der Spiegel English edition, Retrieved 1 June 2014

- ^ "Nigeria: Deaths of hundreds of Boko Haram suspects in custody requires investigation". Amnesty International. 15 October 2013. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- ^ "Nigerian government fails to prevent further kidnappings by Boko Haram". Nigeria Sun. 16 August 2014. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Department of Public Information • News and Media Division • New York (22 May 2014). "SECURITY COUNCIL AL-QAIDA SANCTIONS COMMITTEE ADDS BOKO HARAM TO ITS SANCTIONS LIST". UN Security Council. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- ^ a b Paul Newman (2013). "The Etymology of Hausa boko" (PDF). Mega-Chad Research Network. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Dr. Aliyu U. Tilde. "An in-house Survey into the Cultural Origins of Boko Haram Movement in Nigeria". Retrieved 24 July 2014.

- ^ http://www.csmonitor.com/World/Security-Watch/Backchannels/2014/0506/Boko-Haram-doesn-t-really-mean-Western-education-is-a-sin

- ^ http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052702303701304579549603782621352

- ^ "Nigeria committing 'war crimes' to defeat Boko Haram". The Independent. 17 August 2014. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Nigeria's Maiduguri bans motorbikes to stop Boko Haram". News. BBC. 8 July 2011.

- ^ Committee on Homeland Security (November 30, 2011). "BOKO HARAM Emerging Threat to the U.S. Homeland" (PDF). US House of Representatives. Retrieved September 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Aminu Abubakar (16 July 2014). "Gunmen nab German in northeast Nigeria". Yahoo News. Retrieved 26 July 2014.

- ^ "Nigeria: Boko Haram's Funding Sources Uncovered". AllAfrica. 12 February 2012. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ^ Adisa, Taiwo (13 February 2012). "Boko Haram's funding traced to UK, S. Arabia". Nigerian Tribune. Archived from the original on 14 February 2012.

- ^ Ogundipe, Taiwo (29 January 2012). "Tracking the sect's cash flow". The Nation. Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- ^ "'Why We Did Not Kill Obasanjo' – Boko Haram Leader". 24/7 u reports. 23 January 2012. Archived from the original on 17 April 2012. Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- ^ "Boko haram funding: Nigeria may face international sanctions – Security beefed up in Benue as Boko Haram gives notice to strike". Nigerian Tribune. 21 May 2012.

- ^ Lansana Gberie (January 22, 2013). "Review of Africa and the War on Drugs". World Peace Foundation. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ James Cockayne (October 19, 2012). "Africa and the War on Drugs: the West African cocaine trade is not just business as usual". African Arguments. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Tim Cocks (Fri May 9). "Boko Haram exploits Nigeria's slow military decline". Reuters. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Oscar Nkala (29 July 2014). "Nigeria tops world terror attack fatality list". defenseWeb. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- ^ FELIX ONUOH (17 February 2014). "Nigeria Islamists better armed, motivated than army: governor". Reuters. Retrieved 26 July 2014.

External links

- Boko Haram: Its Beginnings, Principles and Activities in Nigeria (PDF), PDF: Islamic Studies Department, University of Bayero.

- The Boko Haram Uprising and Islamic Revivalism in Nigeria, Africa Spectrum

- Anatomy: African Terrorism, World Policy Blog

- Who Are Boko Haram?, Muslim Institute

- In Nigeria False Prophets Are Real Problems, World Defense Review

- The Origins of Boko Haram, The National Interest

- Nigeria's Troubled North: Interrogating the Drivers of Public Support for Boko Haram (PDF), International Centre For Counter-Terrorism, The Hague

- Security Forces Abuses, Human Rights Watch.

- Boko Haram Special Report, United States Institute of Peace.

- Confronting the Terrorism of Boko Haram in Nigeria, JSOU

- More information on Boko Haram

- Who are Boko Haram? (CNN)

- Analysis of Boko Haram on IRIN News

- Timeline on IRIN News

- Former U.S. Ambassador to Nigeria arguing that Boko Haram is not a formal terrorist group

- Books versus bullets in north-east Nigeria RFI English

- Boko Haram's Evolving Threat, Africa Center for Strategic Studies

- Boko Haram Council on Foreign Relations

- Boko Haram: An Annotated Bibliography Stuart Elden

- Boko Haram. Islamism, politics, security and the State in Nigeria Ed. by Marc-Antoine Pérouse de Montclos. Leiden, African Studies Centre, 2014. ISBN 9789054481355

- Use dmy dates from October 2012

- Boko Haram

- Religion in Nigeria

- 2002 establishments in Nigeria

- Islamic Extremism in Northern Nigeria

- Islamism in Nigeria

- Islamist groups

- Jihadist organizations

- Organizations designated as terrorist by the United States government

- Organizations designated as terrorist in Africa

- Rebel groups in Nigeria

- Religious organizations established in 2002

- United Kingdom Home Office designated terrorist groups

- Government of New Zealand designated terrorist organizations