Saint George: Difference between revisions

| [pending revision] | [pending revision] |

m →Georgia: replacing the s I accidentally deleted |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

{{dablink|For other senses of this name, see [[Saint George (disambiguation)]].}} |

{{dablink|For other senses of this name, see [[Saint George (disambiguation)]].}} |

||

In [[Hagiography|Christian hagiography]] '''Saint George''' (c. 275-281–[[April 23]], [[303]]) was a [[soldier]] of the [[Roman Empire]] who was venerated as a [[Christian]] [[martyr]]. Saint George is the most venerated saint in [[Orthodox Christianity]]. Immortalised in the tale of [[Saint George and the Dragon|George and the Dragon]], he is the [[patron saint]] of several countries, including [[England]], [[Ethiopia]], [[Georgia (country)|Georgia]], [[Montenegro]], and the city of [[Moscow]], as well as a wide range of professions, organisations and disease sufferers. |

In [[Hagiography|Christian hagiography]] '''Saint George''' (c. 275-281–[[April 23]], [[303]]) was a [[soldier]] of the [[Roman Empire]] who was venerated as a [[Christian]] [[martyr]]. Saint George is the most venerated saint in [[Orthodox Christianity]]. Immortalised in the tale of [[Saint George and the Dragon|George and the Dragon]], he is the [[patron saint]] of several countries, including [[England]], [[Ethiopia]], [[Georgia (country)|Georgia]], [[Montenegro]], [[Catalonia]] and the city of [[Moscow]], as well as a wide range of professions, organisations and disease sufferers. |

||

==Life== |

==Life== |

||

Revision as of 22:28, 7 December 2006

Saint George | |

|---|---|

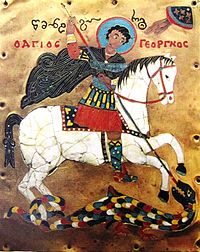

A 15th-century plaque from Georgia portraying St George | |

| Born | ca. AD 270 Lydda, Palestine |

| Died | ca. AD 303 Nicomedia, Bithynia |

| Venerated in | Christianity |

| Major shrine | St. George's Church, Lod |

| Feast | April 23 |

| Attributes | Lance, Dragon, Horseback Rider, Knighthood, St George's Cross |

| Patronage | Amersfoort, Netherlands; Aragon; agricultural workers; archers; armourers; Beirut, Lebanon; Boy Scouts; butchers; Cappadocia; Catalonia; cavalry; chivalry; Constantinople; Corinthians (Brazilian soccer team);Crusaders; England (by Pope Benedict XIV); equestrians; Ethiopia; farmers; Ferrara, Italy; field workers; Genoa; Georgia; Gozo; Greece; Haldern, Germany; Heide; herpes; horsemen; horses; husbandmen; Istanbul; knights; lepers; leprosy; Lithuania; Lod; Malta; Modica, Sicily; Moscow; Order of the Garter; Palestine; Palestinian Christians; plague; Portugal; Ptuj, Slovenia; riders; saddle makers; sheep; shepherds; skin diseases; soldiers; syphilis; Teutonic Knights; Venice [1] |

In Christian hagiography Saint George (c. 275-281–April 23, 303) was a soldier of the Roman Empire who was venerated as a Christian martyr. Saint George is the most venerated saint in Orthodox Christianity. Immortalised in the tale of George and the Dragon, he is the patron saint of several countries, including England, Ethiopia, Georgia, Montenegro, Catalonia and the city of Moscow, as well as a wide range of professions, organisations and disease sufferers.

Life

There are no historical sources on Saint George.[1] The legend that follows is synthesized from early and late hagiographical sources, such as the Golden Legend, which is the most familiar version in English, since William Caxton's first translation.

George was born to a Christian family during the late 3rd century. His father was from Cappadocia and served as an officer of the army. His mother was from Lydda, Palestine. She returned to her native city as a widow along with her young son, where she provided him with an education.

The youth followed his father's example by joining the army soon after coming of age. He proved to be a good soldier and consequently rose through the military ranks of the time. By his late twenties he had gained the title of Tribunus (Tribune) and then Comes (Count), at which time George was stationed in Nicomedia as a member of the personal guard attached to Roman Emperor Diocletian.

According to the hagiography, in 303 Diocletian issued an edict authorizing the systematic persecution of Christians across the Empire. His caesar, Galerius, was supposedly responsible for this decision and would continue the persecution during his own reign (305–311). George was ordered to take part in the persecution but instead confessed to being a Christian himself and criticized the imperial decision. An enraged Diocletian ordered the torture of this apparent traitor, and his execution.

After various tortures, George was executed by decapitation before Nicomedia's defensive wall on April 23, 303. The witness of his suffering convinced Empress Alexandra and Athanasius, a pagan priest, to become Christians as well, and so they joined George in martyrdom. His body was returned to Lydda for burial, where Christians soon came to honour him as a martyr.

Veneration as a martyr

A church built in Lydda during the reign of Constantine I (reigned 306–337), was consecrated to "a man of the highest distinction", according to the church history of Eusebius of Caesarea; the name of the patron was not disclosed, but later he was asserted to have been George. The church was destroyed in 1010 but was later rebuilt and dedicated to Saint George by the Crusaders. In 1191 and during the conflict known as the Third Crusade (1189–1192), the church was again destroyed by the forces of Saladin, Sultan of the Ayyubid dynasty (reigned 1171–1193). A new church was erected in 1872 and is still standing.

During the fourth century the veneration of George spread from Palestine to the rest of the Eastern Roman Empire, though the martyr is not mentioned in the Syriac Breviarium[2] and Georgia. In Georgia the feast day on November 23 is credited to St Nino of Cappadocia, who in Georgian hagiography is a relative of St George, credited with bringing Christianity to the Georgians in the fourth century. By the fifth century the cult of Saint George had reached the Western Roman Empire as well: in 494, George was canonised as a saint by Pope Gelasius I, among those "whose names are justly reverenced among men, but whose acts are known only to God." According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, the earliest text preserving fragments of George's narrative is in an Acta Sanctorum identified by Hippolyte Delehaye of the scholarly Bollandists to be a palimpsest of the fifth century. The compiler of this Acta, according to Delehaye "confused the martyr with his namesake, the celebrated George of Cappadocia, the Arian intruder into the see of Alexandria and enemy of St. Athanasius".

Hymn of Saint George

Liberator of captives, and defender of the poor, physician of the sick, and champion of kings, O trophy-bearer, and Great Martyr George, intercede with Christ our God that our souls be saved.

Sources

A critical edition of the Syriac Acta of Saint George, accompanied by an annoted English translation was published by E.W. Brooks (1863-1955) in 1925. The hagiography was originally written in Greek.

George and the Dragon

The episode of St George and the Dragon was Eastern in origin,[3] brought back with the Crusaders and retold with the courtly appurtenances belonging to the genre of Romance (Loomis; Whatley). The earliest known depiction of the mytheme is from early eleventh-century Cappadocia (Whately), (in the iconography of Eastern Orthodoxy, George had been depicted as a soldier since at least the seventh century); the earliest known surviving narrative text is an eleventh-century Georgian text (Whatley).

In the fully-developed Western version, a dragon makes its nest at the spring that provides water for the city of Cyrene in Libya or the city of Lydda, depending on the source. Consequently, the citizens have to dislodge the dragon from its nest for a time, in order to collect water. To do so, each day they offer the dragon a human sacrifice. The victim is chosen by drawing lots. One day, this happened to be the princess. The monarch begs for her life with no result. She is offered to the dragon, but there appears the saint on his travels. He faces the dragon, slays it and rescues the princess. The grateful citizens abandon their ancestral paganism and convert to Christianity.

The dragon motif was first combined with the standardized Passio Georgii in Vincent of Beauvais' encyclopedic Speculum historale and then in Jacobus de Voragine, Golden Legend, which guaranteed its popularity in the later Middle Ages as a literary and pictorial subject (Whatly).

The parallels with Perseus and Andromeda are inescapable. In the allegorical reading, the dragon embodies a suppressed pagan cult.[4] The story has roots that predate Christianity. Examples such as Sabazios, the sky father, who was usually depicted riding on horseback, and Zeus's defeat of Typhon the Titan in Greek mythology, along with examples from Germanic and Vedic traditions, have led a number of historians, such as Loomis, to suggest that George is a Christianized version of older deities in Indo-European culture.

In the medieval romances, the lance with which St George slew the dragon was called Ascalon, named after the city of Ashkelon in Palestine, now part of modern day Israel. [5] In some accounts,[citation needed] the dragon is named Stihdjia.

In Sweden, the princess rescued by Saint George is held to represent the kingdom of Sweden, while the dragon represents an invading army. Several sculptures of Saint George battling the dragon can be found in Stockholm, the earliest inside Storkyrkan ("The Great Church") in the Old Town.

Iconography

St. George is most commonly depicted in early icons, mosaics and frescos wearing armour contemporary with the depiction, executed in gilding and silver colour, intended to identify him as a Roman soldier. After the Fall of Constantinople and the association of St George with the crusades, he is more often portrayed mounted upon a white horse. At the same time St George began to be associated with St. Demetrius, another early soldier saint. When the two saints are portrayed together mounted upon horses, they may be likened to earthly manifestations of the archangels Michael and Gabriel. St George is always depicted in Eastern traditions upon a white horse and St. Demetrius on a red horse[6] St George can also be identified in the act of spearing a dragon, unlike St Demetrius, who is sometimes shown spearing a human figure, understood to represent Maximian.

Later depictions and occurrences

During the early 2nd millennium, George came to be seen as the model of chivalry, and during this time was depicted in works of literature, such as the medieval romances.

Jacobus de Voragine, Archbishop of Genoa, compiled the Legenda Sanctorum, (Readings of the Saints) also known as Legenda Aurea (the Golden Legend) for its worth among readers. Its 177 chapters (182 in other editions) contain the story of Saint George.

Colours

The "Colours of Saint George", or St George's Cross) are a white flag with a red cross, frequently borne by entities over which he is patron (e.g. England, Georgia, Liguria, Catalonia etc).

The origin of the St George's Cross came from the earlier plain white tunics worn by the early crusaders.

The same colour scheme was used by Viktor Vasnetsov for the facade of the Tretyakov Gallery, in which some of the most famous St. George icons are exhibited and which displays St. George as the coat of arms of Moscow over its entrance.

Patronage and remembrance

In 1969, Saint George's feast day was reduced to an optional memorial in the Roman Catholic calendar; the solemnity of his commemoration depends on purely local observance. He is, however, still honoured as a saint of major importance by Eastern Orthodoxy.

England

The cult of St George probably first reached the Kingdom of England when the crusaders returned from the Holy Land in the 12th century. King Edward III of England (reigned 1327 – 1377) was known for promoting the codes of knighthood and in 1348 founded the Order of the Garter. During his reign, George came to be recognised as the patron saint of England; prior to this, Saint Edmund had been considered the patron saint of England, although his veneration had perhaps waned since the time of the Norman conquest. Edward dedicated the chapel at Windsor Castle to the soldier saint who represented the knightly values of chivalry which he so much admired, and the Garter ceremony takes place there every year. In the 16th Century, William Shakespeare firmly placed St George within the national conscience in his play Henry V in which the English troops are rallied with the cry “God for Harry, England and St George.”

On June 2 1893, Pope Leo XIII demoted St George as Patron Saint for the English, relegating him to the secondary rank of 'national protector' and replaced him with St Peter as the Patron Saint of England. The change was solemnly announced by Cardinal Herbert Vaughan in the Brompton Oratory. This papal pronouncement served to exclude the Catholic Church in England from a day which is part of English tradition. In 1963, in the Roman Catholic Church, St George was further demoted to a third class minor saint and removed him from the Universal Calendar, with the proviso that he could be honoured in local calendars. Pope John Paul II, in 2000, restored St George to the Calendar, and he appears in Missals as the English Patron Saint, with Pope Leo’s pronouncement ignored.

With the revival of Scottish and Welsh nationalism, there has been renewed interest within England in St George, whose memory had been in abeyance for many years. This is most evident in the St George's flags which now have replaced Union Flags in stadiums where English sports teams compete. Nevertheless, St George’s Day still remains a relatively low-key affair with the City of London not publicly celebrating the patron saint. However, the City of Salisbury does hold an annual St George’s Day pageant, the origins of which are believed to go back to the thirteenth century.

Georgia

Saint George is a patron saint of Georgia. According to Georgian author Enriko Gabisashvili, Saint George is most venerated in the nation of Georgia. An 18th century Georgian geographer and historian Vakhushti Bagrationi wrote that there are 365 Orthodox churches in Georgia named after Saint George according to the number of days in a one year. [7] There are indeed many churches in Georgia named after the Saint and Alaverdi Monastery is one of the largest.

The Georgian Orthodox Church commemorates St. George's day twice a year, on May 6 (O.C. April 23) and November 23. The feast day in November was instituted by St Nino of Cappadocia, credited with bringing Christianity to the Georgians in the fourth century. She was from Cappadocia like Saint George and was his relative. This feast day is unique to Georgia and it is the day of St. George's martyrdom.

There are also many folk traditions in Georgia that vary from Georgian Orthodox Church rules, because they portray the Saint differently than the Church does and show the veneration of Saint George in common people of Georgia. Different regions of Georgia have different traditions and in most folk tales Saint George is adored as Christ himself. Kakheti province has the icon of White George. White George is also seen on the current Coat of Arms of Georgia. Pshavi region has the icons of Cuppola St. George and Lashari St. George. Khevsureti region has Kakhmati, Gudani, Sanebi icons dedicated to the Saint. Pshavs and Khevsurs used to call Saint George the God while they prayed in the Middle Ages. Another notable icon is Lomisi Saint George in Mtiuleti and Khevi provinces of Georgia. [8]

An example of folk tale about St. George: Once Jesus Christ, prophet Elijah and St. George were going through Georgia. When they became tired and hungry they stopped to dine. They saw a Georgian shepherd man and decided to ask him to feed them. First, Elijah went up to the shepherd and asked him for a sheep. After the shepherd asked his identity Elijah said that, he was the one who sent him rain to get him a good profit from farming. The shepherd became angry at him and told him that he was the one who also sent thunderstorms, which destroyed the farms of poor widows.

After Elijah, Jesus Christ himself went up to the shepherd and asked him for a sheep and told him that he was the god, the creator of everything. The shepherd became angry at Jesus and told him that he is the one who takes the souls away of young men and grants long lives to many dishonest people.

After Elijah and Christ's unsuccessful attempts, St. George went up to the shepherd, asked him for a sheep and told him that he is Saint George who the shepherd calls upon everytime when he has troubles and St. George protect him from all the evil and saves him from troubles. After hearing St. George, the shepherd fell down on his knees and adored him and gave him everything. This folk tale shows the veneration of St. George in the Middle Ages provinces of Georgia and similar tales are told in the northern mountainous parts of the country.[9]

An interesting facts are Georgian sources, some of which are testified by Persian ones, that Georgian Army during the battles were led by the knight on the white horse who came down from the heaven. Catholicos Besarion of Georgia also testified this fact.

Iberian Penninsula

On the Iberian peninsula, George also came to be considered as patron to the Crown of Catalonia and Aragon (Aragon, Catalonia, Valencia and Majorca; Catalan: Sant Jordi) and Portugal (Portuguese language: São Jorge) during their struggles against Castile. Their previous patron Saint James the Great was considered more strongly connected to Castile. Already connected in accepting George as their patron saint, in 1386 England and Portugal agreed to an Anglo-Portuguese Alliance. Today this treaty between the United Kingdom and Portugal is still in force.

His feast date, April 23, is the Day of Aragon (Spain) and is also the a very important holiday in Catalonia, where it is traditional to give a rose and a book to the loved one. This, together with the anniversary of the deaths, in 1616, of Cervantes and Shakespeare, has led UNESCO to declare April 23 World Book and Copyright Day.

Greece

In Greece, St. George is the patron saint of the Hellenic Army. His image adorns all regimental battle flags (Colours), and military parades are held in his honour on 23 April every year in most army garrison towns and cities.

United States

In the US Armed Forces, St. George is seen as the patron saint of Armored Forces [citation needed] as he is the only saint depicted as fighting while mounted. The St. George Medal is awarded to officers and high ranking non-commissioned officers serving in command positions at the battalion or company level [citation needed].

Freemasons

The Freemasons consider St. George one of their primary patron saints. The United Grand Lodge of England holds its annual festival on a day as near as possible to St. George's Day, and St. George is depicted on the ceiling of the Grand Lodge Temple on Great Queen Street, London. A number of Masonic lodges around the world bear the name of St. George.

Scouting

St George's Day is also celebrated with parades in those countries of which he is the patron saint. Also, St George is the patron saint of Scouting. On St George's day (or the closest Sunday), Scouts from around the world generally take part in a parade and some kind of church service in which they renew their Scout Promise. The St. George Award is the highest rank attainable by a Baden-Powell Scout, a world-wide Scouting movement founded in England.

Other

He is also apparently the patron saint of skin desease sufferers and syphilitic people. (see)

Muslim world

In Islamic cultures, the Prophet or Saint al-Khidr or Khizar; according to the Quran a companion of the Prophet Muwsa Moses, is associated with Jirjis (St. George), who is also venerated under that name by Christians among mainly Muslim people, especially Palestinian people, and mainly around Jerusalem, where according to tradition he lived and often prayed near the Temple Mount, and is venerated as a protector in times of crisis. His main monument is the elongated mosque Qubbat al-Khidr ('The Dome of al-Khidr') which stands isolated from any close neighbors on the northwest corner of the Dome of the Rock terrace in Jerusalem.

Notes

- ^ The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge omitted Saint George.

- ^ Butler.

- ^ Robertson, The Medieval Saints' Lives (pp 51-52) suggested that the dragon motif was transferred to the George legend from that of his fellow soldier saint, Saint Theodore Tiro. The Roman Catholic writer Alban Butler (Lives of the Saints) was at pains to credit the motif as a late addition: "It should be noted, however, that the story of the dragon, though given so much prominence, was a later accretion, of which we have no sure traces before the twelfth century. This puts out of court the attempts made by many folklorists to present St. George as no more than a christianized survival of pagan mythology."

- ^ Loomis 1948:65 and notes 111-17, giving references to other saints' encounters with dragons. "To Loomis's list might be added the stories of Martha . . . and Silvester, which is vigorously summarized (from a fifth-century version of the Actus Silvestri) by the early English writer, Aldhelm, abbot of Malmesbury (639-709), in his De Virginitate (see Aldhelm: The Prose Works, pp. 82-83). On dragons and saints, see now Rauer, Beowulf and the Dragon." (Whatley 2004). Saint Mercurialis, the first bishop of the city of Forlì, in Romagna, is often portrayed in the act of killing a dragon.

- ^ Incidentally, the name Ascalon was used by Winston Churchill for his personal aircraft during World War II, according to records at Bletchley Park.

- ^ The red pigment may appear black if it has bitumenized.

- ^ Gabidzashvili, Enriko. 1991. Saint George: In Ancient Georgian Literature. Armazi - 89: Tbilisi, Georgia.

- ^ Gabidzashvili, Enriko. 1991. Saint George: In Ancent Georgian Literature. Armazi - 89: Tbilisi, Georgia.

- ^ Gabidzashvili, Enriko. 1991. Saint George: In Ancent Georgian Literature. Armazi - 89: Tbilisi, Georgia.

See also

- Khidr

- Georgslied, 9th-century Old High German poem about the life of Saint George

- Knights of St. George

- Bristol, England, which has a district christened Saint George and also a park bearing that name

- St. George's Day

- Paladin

- Dragon Hill, Uffington

- St George's Church, churches dedicated to St. George

- The Magic Sword, 1961 film loosely based on the legend of St. George and the Dragon

References

- Brooks, E.W., 1925. Acts of Saint George in series Analecta Gorgiana 8 (Gorgias Press).

- Burgoyne, Michael H. 1976. A Chronological Index to the Muslim Monuments of Jerusalem. In The Architecture of Islamic Jerusalem. Jerusalem: The British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem.

- Alban Butler , Butler's Lives of the Saints, vol. 2, pp. 148-150. "George, Martyr, Protector of the Kingdom of England" (on-line text)

- Gabidzashvili, Enriko. 1991. Saint George: In Ancent Georgian Literature. Armazi - 89: Tbilisi, Georgia.

- Loomis, C. Grant, 1948. White Magic, An Introduction to the Folklore of Christian Legend (Cambridge: Medieval Society of America)

- Natsheh, Yusuf. 2000. "Architectural survey", in Ottoman Jerusalem: The Living City 1517-1917. Edited by Sylvia Auld and Robert Hillenbrand (London: Altajir World of Islam Trust) pp 893-899.

- Whatley, E. Gordon, editor, with Anne B. Thompson and Robert K. Upchurch, 2004. St. George and the Dragon in the South English Legendary (East Midland Revision, c. 1400) Originally published in Saints' Lives in Middle English Collections

(Kalamazoo, Michigan: Medieval Institute Publications) (On-line Introduction)

External links

- Bulgaria - St. George's Day

- (Emel Muslim magazine) A very modern patron: Muslims and St George

- Archnet

- Saint George and the Dragon links and pictures (more than 125), from Dragons in Art and on the Web

- Catholic hagiography

- Saint George and the Boy Scouts, including a woodcut of a Scout on horseback slaying a dragon

- The Elevation of St George

- A prayer for St George's Day

- The English & St. George's Day

- St. George

- [http://www.lib.rochester.edu/camelot/teams/whgeodintro.htm