Turks in Libya: Difference between revisions

Undid revision 934218723 by Selçuk Denizli (talk) multiple redlinks |

Undid revision 934231354 by Viewmont Viking (talk) They are still notable people. Red links do not mean former ministers etc. should be deleted from the list. |

||

| Line 97: | Line 97: | ||

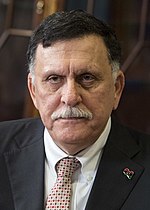

[[File:Fayez al-Sarraj in Washington - 2017 (38751877521) (cropped).jpg|thumb|150px|right|[[Fayez al-Sarraj]] is the prime minister of the [[Government of National Accord]].]] |

[[File:Fayez al-Sarraj in Washington - 2017 (38751877521) (cropped).jpg|thumb|150px|right|[[Fayez al-Sarraj]] is the prime minister of the [[Government of National Accord]].]] |

||

[[File:الدكتور عبد الرحمن السويحلي.jpg|thumb|150px|right|[[Abdulrahman Sewehli|Abdel Rahman al-Suwayhili]] is the leader of the [[Union for Homeland]].]] |

[[File:الدكتور عبد الرحمن السويحلي.jpg|thumb|150px|right|[[Abdulrahman Sewehli|Abdel Rahman al-Suwayhili]] is the leader of the [[Union for Homeland]].]] |

||

*[[Fathi Pasha Agha]], Interior Minister<ref>{{citation|last=|first=|year=2019|title=يحن لأصوله التركية .. فتحي آغا مؤسس ميليشيات حرق ليبيا|url=https://3thmanly.com/ar/article/يحن-لأصوله-التركية-فتحي-آغا-مؤسس-مليشيات-حرق-ليبيا|publisher=3thmanly|accessdate=22 September 2019}}</ref> |

|||

*[[Salah Badi]], commander of the Al-Somood Front<ref name=Tastekin/> |

|||

*[[Fathi Bashagha]], heads the Interior Ministry<ref name=Tastekin/> |

*[[Fathi Bashagha]], heads the Interior Ministry<ref name=Tastekin/> |

||

*[[Husni Bey]], business tycoon<ref>{{citation|last=|first=|year=2019|title=حسني بي: أنا من ضمن المليون تركماني في ليبيا|url=https://www.alsaaa24.com/2019/12/23/%D8%AD%D8%B3%D9%86%D9%8A-%D8%A8%D9%8A-%D8%A3%D9%86%D8%A7-%D9%85%D9%86-%D8%B6%D9%85%D9%86-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85%D9%84%D9%8A%D9%88%D9%86-%D8%AA%D8%B1%D9%83%D9%85%D8%A7%D9%86%D9%8A-%D9%81%D9%8A-%D9%84/|publisher=Alsaaa24|accessdate=2 January 2020}}</ref> |

|||

*[[Wissam Bin Hamid]], commander in the [[Libya Dawn]]<ref name=Tastekin/> |

|||

*[[Mukhtar al-Jahawi]], commander of the Anti-Terrorism Force<ref name=Tastekin/> |

|||

*[[Abdul Rauf Kara]], leader of the [[RADA Special Deterrence Forces|Special Deterrence Force]]<ref name=Tastekin/> |

|||

*[[Ahmed Karamanli]], founded the [[Karamanli dynasty]] (1711–1835)<ref>{{citation|last=Habib|first=Henry|year=1981|title=Libya: Past and Present|publisher=Edam Publishing House|isbn=|page=42}}</ref> |

*[[Ahmed Karamanli]], founded the [[Karamanli dynasty]] (1711–1835)<ref>{{citation|last=Habib|first=Henry|year=1981|title=Libya: Past and Present|publisher=Edam Publishing House|isbn=|page=42}}</ref> |

||

**successors: |

**successors: |

||

| Line 109: | Line 115: | ||

**[[Mehmed ibn Ali]] (1824 and 1835) |

**[[Mehmed ibn Ali]] (1824 and 1835) |

||

**[[Ali II Karamanli]] (20 August 1832 - 26 May 1835) |

**[[Ali II Karamanli]] (20 August 1832 - 26 May 1835) |

||

*[[Umar al-Mahashi]], Minister of Planning<ref>{{citation|last=Ahmida|first=Ali Abdullatif|year=2013|title=Forgotten Voices: Power and Agency in Colonial and Postcolonial Libya|publisher=Routledge|isbn=1136784438|page=79-80}}</ref> |

|||

*[[Omar Pasha Mansour El Kikhia]], first prime minister of [[Cyrenaica]]<ref>{{citation|last=Villard|first=Henry Serrano|year=1956|title=Libya: The New Arab kingdom of North Africa|url=https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=15GRAAAAIAAJ&q=Of+the+different+personalities+in+the+Parliament+which+took+up+its+duties+in+1952,+none+was+so+picturesque+as+Omar+Pasha+Mansour+el+Kekhia,+President+of+the+Senate.+Grand+old+man+of+Libya%27s+tenuous+political+past,+Omar+Pasha+was+as+proud+of+his+Turkish+ancestry+as+he+was+of+his+conjugal+successes%3B&dq=Of+the+different+personalities+in+the+Parliament+which+took+up+its+duties+in+1952,+none+was+so+picturesque+as+Omar+Pasha+Mansour+el+Kekhia,+President+of+the+Senate.+Grand+old+man+of+Libya%27s+tenuous+political+past,+Omar+Pasha+was+as+proud+of+his+Turkish+ancestry+as+he+was+of+his+conjugal+successes%3B&hl=en&sa=X&redir_esc=y|publisher=[[Cornell University Press]]|isbn=|page=56|quote= Of the different personalities in the Parliament which took up its duties in 1952, none was so picturesque as Omar Pasha Mansour el Kekhia, President of the Senate. Grand old man of Libya's tenuous political past, Omar Pasha was as proud of his Turkish ancestry as he was of his conjugal successes;}}</ref> |

|||

*[[Mansour Mohamed El-Kikhia]], academic and politician |

|||

*[[Mansour Rashid El-Kikhia]], Libyan Minister of Foreign Affairs (1972-1973) and Permanent Libyan Representative to the United Nations (1975-1980)<ref>{{citation|last=Alnajjar|first=Tareq|year=1956|title=Who Kidnapped the Former Libyan Minister for Foreign Affairs in Egypt|url=http://www.libya-watanona.com/libya/tareq97.htm|publisher=Libya Watanona|accessdate=22 September 2019}}</ref> |

|||

*[[Sadullah Koloğlu]], former prime minister of [[Benghazi]] and [[Derna, Libya|Darnah]] (from 1949 to 1952)<ref>{{cite web |author=Hurriyet Daily News|title=Turkey's living link to Ottoman Libya: Son of former PM tells father's story|url=http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/default.aspx?pageid=438&n=a-living-link-to-ottoman-libya-son-of-former-pm-tells-father8217s-story-2011-03-04|accessdate=2016-05-15}}</ref> |

|||

*[[Ahmed Maiteeq]], served briefly as Libyan Prime Minister in 2014<ref name=Tastekin/> |

*[[Ahmed Maiteeq]], served briefly as Libyan Prime Minister in 2014<ref name=Tastekin/> |

||

*[[Omar Abdullah Meheishy]], former Member of the [[Libyan Revolutionary Command Council]]<ref>{{citation|last=First|first=R.|year=1974|title=Libya: The Elusive Revolution|publisher=Africana Publishing Company|isbn=0841902119|page=[https://archive.org/details/libyaelusiverevo0000firs/page/115 115]|url=https://archive.org/details/libyaelusiverevo0000firs/page/115}}</ref> |

|||

*[[Shaha Riza]] |

*[[Shaha Riza]] |

||

*[[Muhammad Sakizli]], Libyan politician |

*[[Muhammad Sakizli]], Libyan politician |

||

*[[Ali al-Sallabi]], historian and Islamist<ref name=Tastekin/> |

*[[Ali al-Sallabi]], historian and Islamist<ref name=Tastekin/> |

||

*[[Fayez al-Sarraj]], Chairman of the [[Presidential Council (Libya)|Presidential Council of Libya]] and prime minister of the [[Government of National Accord]]<ref name=Tastekin/> |

*[[Fayez al-Sarraj]], Chairman of the [[Presidential Council (Libya)|Presidential Council of Libya]] and prime minister of the [[Government of National Accord]]<ref name=Tastekin/> |

||

**father: [[Mostafa al-Sarraj]], former minister |

|||

*[[Mohamed Sowan]], leader of the [[Justice and Construction Party]]<ref name=Tastekin/> |

*[[Mohamed Sowan]], leader of the [[Justice and Construction Party]]<ref name=Tastekin/> |

||

*[[Abdulrahman Sewehli|Abdel Rahman al-Suwayhili]], Parliament member and founder of the [[Union for Homeland]]<ref name=Tastekin/> |

*[[Abdulrahman Sewehli|Abdel Rahman al-Suwayhili]], Parliament member and founder of the [[Union for Homeland]]<ref name=Tastekin/> |

||

*[[Ramadan Asswehly|Ramadan al-Suwayhili]], a co-founder of the short-lived [[Tripolitanian Republic]] in 1918<ref name=Tastekin/> |

*[[Ramadan Asswehly|Ramadan al-Suwayhili]], a co-founder of the short-lived [[Tripolitanian Republic]] in 1918<ref name=Tastekin/> |

||

*[[Hassan Tatanaki]], businessman<ref name="AT">{{citation|last=Fawzi|first=Osama|year=2007|title=|url=http://www.arabtimes.com/2007/Feb/116.html|publisher=[[Arab Times]]|accessdate=29 January 2018}}</ref> |

*[[Hassan Tatanaki]], businessman<ref name="AT">{{citation|last=Fawzi|first=Osama|year=2007|title=|url=http://www.arabtimes.com/2007/Feb/116.html|publisher=[[Arab Times]]|accessdate=29 January 2018}}</ref> |

||

*[[Hamida al-Unayzi]], champion of women’s education in Libya<ref>{{citation|last=Yeaw|first=Katrina Elizabeth Anderson|year=2017|title=Women, Resitance and the Creation of New Gendered Frontiers in the Making of Modern Libya, 1890-1980|publisher=Georgetown University|isbn=|page=152}}</ref> |

|||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

Revision as of 15:58, 5 January 2020

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| Total Libyan-Turkish minority: 1,000,000[1] to 1,400,000 (including Libyans of full or partial Turkish ancestry, 2019 estimate)[2][3] or at least one in four Libyans of Turkish origin (i.e. 20%-25% of the country's population, 2019 estimate)[3][4] Cretan Turks only: 100,000 (1971 estimate)[5] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Religion | |

| Islam |

The Turks in Libya, also commonly referred to as Libyan Turks,[2] Turco-Libyans,[2] and Turkish-Libyans[4] (Arabic: أتراك ليبيا; Turkish: Libya Türkleri; Italian: Turco-libici) are the ethnic Turks who live in Libya. According to the last census which allowed citizens to declare their ethnicity, the Turks formed the third largest ethnic group in the country after the Arabs and Berbers.[6] The community mainly live in Misrata, Tripoli, Zawiya, Benghazi and Derna.

During Ottoman rule in Libya (1551–1912), Turkish settlers began to migrate to the region predominately from Anatolia, but also from other parts of the empire - such as the island of Crete. A significant number of Turks intermarried with the native population, and the male offspring of these marriages were referred to as Kouloughlis (Turkish: kuloğlu) due to their mixed heritage.[7][8] However, in general, intermarriage was discouraged, in order to preserve the "Turkishness" of the community. Consequently, the terms "Turks" and "Kouloughlis" have traditionally been used to distinguish between those of full and partial Turkish ancestry.[9][10][7] The Turkish community has traditionally dominated the political life of Libya.

After the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire, Turks continued to migrate to Libya from the newly established modern states, particuarly from the Republic of Turkey, but also from other regions with significant Turkish settlements such as Cyprus and Egypt.

When the Libyan Civil War erupted in 2011, Misrata became “the bastion of resistance” and Turco-Libyans figured prominently in the war.[2] In 2014 a former Gaddafi officer reported to the New York Times that the civil war was now an "ethnic struggle" between Arab tribes (like the Zintanis) against those of Turkish ancestry (like the Misuratis), as well as against the Berbers and Circassians.[11]

History

Ottoman Libya

When the Ottoman Empire conquered Libya in 1551 the Turks began migrating to the region mostly from Anatolia, including merchants and families. In addition, many Turkish soldiers married Arab or Berber women and their children were known as the "Kouloughlis" (also referred to as the "Cologhla", "Qulaughli" and "Cologhli").[12]

Today there are still Libyans who regard their ethnicity as Turkish, or acknowledge their descendants to the Turkish soldiers who settled in the area during the Ottoman rule.[13] Indeed, many families in Libya can trace their origins through their surnames. It is very common for families to have surnames that belong to the region of Turkey that their ancestors migrated from; for example, Tokatlı, Eskişehirli, Muğlalı, and İzmirli are very common surnames.[14][15]

Italian Libya

After Libya fell to the Italians in 1911, most Turks still remained in the region. According to the census conducted by the Italian colonialists in 1936 the Turkish community formed 5% of Libya's population,[6] of which 30,000 lived along the Tripolitanian coast.[12]

1936 census

The last census which allowed the Turkish minority to declare their ethnicity showed the following:

| Administrative division | Turks (1936 census)[16] | % of Libya's total population[16] |

|---|---|---|

| Province of Misurata | 24,820 | 11.6% |

| Province of Tripoli | 5,848 | 1.7% |

| Libyan Sahara | 3,341 | 6.9% |

| Province of Derna | 730 | 1.8% |

| Province of Benghazi | 323 | 0.3% |

| Libya, Total | 35,062 | 4.7% |

Modern migration to the State of Libya

Initially, modern Turkish labour migration has traditionally been to European countries within the context of bilateral agreements; however, a significant wave of migration also occurred in oil-rich nations like Libya and Saudi Arabia.[17][18][19]

Durung Abd al-Salam Jallud's visit to Turkey in January 1975, a ‘breakthrough collaboration agreement’ was signed which involved sending 10,000 skilled Turkish workers to Libya, in order to expand the country’s oil-rich economy.[20] This agreement also included a Libyan commitment to supply crude oil to Turkey ‘at preferential rates’ and to establish a Turkish–Libyan Bank. By August, 1975, Libya announced its desire ‘to absorb up to 100,000 Turkish workers annually’.[20]

The Libyan–Turkish economic ties increased significantly with the number of Turkish construction companies operating in Libya in 1978–81 rising from 2 to 60, and by 1984, to 150.[21] Moreover, in 1984, the number of Turkish "guest workers" in Libya increased to 120,000.[21]

Demographics

There is a significant Turkish community living in the north-west of Libya. For example, many Turks settled in Misrata during the reign of Abdul Hamid II in the nineteenth century.[14][15]

In 1971 the population of Turks with roots from the island of Crete alone numbered 100,000.[5] In 2014, Ali Hammuda, who served as the Minister of Foundations and Religious Affairs of Libya, claimed that the Turkish minority forms 15% of Libya's total population.[22] More recent estimates in 2019 suggest that the total Turkish population in Libya is around 1.4 million,[2] or that more than one in four Libyans (i.e. 25% of the country's population) have Turkish ancestry.[4][3]

The city of Misrata is considered to be the "main center of the Turkish-origin community in Libya";[23] in total, the Turks form approximately two-thirds (est.270,000[24]) of Misrata's 400,000 inhabitants.[24][25] There is also a thriving Turkish population in Tripoli.[26] Turkish communities have also been formed in more remote areas of the country, such as the Turkish neighborhood of Hay al-Atrak, in the town of Awbari.[27]

Diaspora

There is a significant Libyan-Turkish community living in Turkey where they are still referred to as "Libyan Turks".[2]

Religion

The Ottoman Turks brought with them the teaching of the Hanafi School of Islam during the Ottoman rule of Libya which still survives among the Turkish descended families today. Examples of Ottoman-Turkish mosques include:

Persecution

Libyan Turks have experienced persecution during Muammar Gaddafi's regime, as Gaddafi favored pan-Arabism and considered the minorities residing in Libya as a threat for Libya's Arabization process. Turks, among with several minority groups, had been forced to abandon their cultural traditions and enforced to behave and act like Arabs.

Khalifa Haftar's Tobruk Government recently has followed anti-Turkish sentiment and denounced Turkey for interference in Libya, raising the fears of re-persecution of Turkish population.

Associations and Organisations

In Libya

- Türk-Libya İşbirliği (The Turkish-Libyan Cooperation), established in 2011[14][15]

- Libya Köroğlu Derneği (The Libyan Kouloughlis Association), established in 2015[14][15]

In Turkey

- The Association of Turks with Libyan Roots, established in 2011[2]

Popular culture

- In Mansour Bushnaf's s debut novel Chewing Gum (2008), Rahma, who is the mother of the main character Mukhtar, is from a Turco-Libyan family. The book was banned during Muammar Gaddafi's regime.

Notable people

- Fathi Pasha Agha, Interior Minister[28]

- Salah Badi, commander of the Al-Somood Front[2]

- Fathi Bashagha, heads the Interior Ministry[2]

- Husni Bey, business tycoon[29]

- Wissam Bin Hamid, commander in the Libya Dawn[2]

- Mukhtar al-Jahawi, commander of the Anti-Terrorism Force[2]

- Abdul Rauf Kara, leader of the Special Deterrence Force[2]

- Ahmed Karamanli, founded the Karamanli dynasty (1711–1835)[30]

- successors:

- Ahmed I (29 July 1711 - 4 November 1745)

- Mehmed Pasha (4 November 1745 - 24 July 1754)

- Ali I Pasha (24 July 1754 - 30 July 1793)

- Ali Burghul Pasha Cezayrli (30 July 1793 - 20 January 1795)

- Ahmed II (20 January - 11 June 1795)

- Yusuf Karamanli (11 June 1795 - 20 August 1832)

- Mehmed Karamanli (1817, 1826, and 1832)

- Mehmed ibn Ali (1824 and 1835)

- Ali II Karamanli (20 August 1832 - 26 May 1835)

- Umar al-Mahashi, Minister of Planning[31]

- Omar Pasha Mansour El Kikhia, first prime minister of Cyrenaica[32]

- Mansour Mohamed El-Kikhia, academic and politician

- Mansour Rashid El-Kikhia, Libyan Minister of Foreign Affairs (1972-1973) and Permanent Libyan Representative to the United Nations (1975-1980)[33]

- Sadullah Koloğlu, former prime minister of Benghazi and Darnah (from 1949 to 1952)[34]

- Ahmed Maiteeq, served briefly as Libyan Prime Minister in 2014[2]

- Omar Abdullah Meheishy, former Member of the Libyan Revolutionary Command Council[35]

- Shaha Riza

- Muhammad Sakizli, Libyan politician

- Ali al-Sallabi, historian and Islamist[2]

- Fayez al-Sarraj, Chairman of the Presidential Council of Libya and prime minister of the Government of National Accord[2]

- father: Mostafa al-Sarraj, former minister

- Mohamed Sowan, leader of the Justice and Construction Party[2]

- Abdel Rahman al-Suwayhili, Parliament member and founder of the Union for Homeland[2]

- Ramadan al-Suwayhili, a co-founder of the short-lived Tripolitanian Republic in 1918[2]

- Hassan Tatanaki, businessman[36]

- Hamida al-Unayzi, champion of women’s education in Libya[37]

See also

References

- ^ الأزمة في ليبيا: هل يشعل إرسال قوات تركية إلى ليبيا فتيل حرب إقليمية؟, BBC Arabic, 2019, retrieved 26 September 2019,

على المنوال ذاته، يقول مشاري الذايدي في الشرق الأوسط اللندنية: "نحن إزاء عدوان تركي بنكهة عثمانية على ليبيا، وطمع بنفطها وغازها وناسها وبرها وبحرها، بل إن رجب طيب أردوغان عبّر صراحة عن هذا الجشع وشرعنه بالحديث مدعيا عن مليون ليبي من أصول تركية يستحقون دعمه والتدخل لنجدتهم".

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Tastekin, Fehim (2019). "Are Libyan Turks Ankara's Trojan horse?". Al-Monitor. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- ^ a b c Scipione, Alessandro (2019), Libia, la mappa dei combattenti stranieri, Inside Over, retrieved 26 September 2019,

La Turchia peraltro può vantare in Livia una numerosa comunità dei "Koroglu" (i libici di discendenza turca) che conterrebbe ben 1,4 milioni di individui, concentrati soprattutto a Misurata, la "città-Stato" situata circa 180 chilometri a est di Tripoli: praticamente meno un libico su quattro in Libia ha origini turche.

- ^ a b c Libia: Lna, turchi vogliono colpire il tessuto sociale e spostare le tribù, Agenzia Nova, 2019, retrieved 26 September 2019,

Almeno un libico su quattro in Libia ha origini turche...

- ^ a b Rippin, Andrew (2008). World Islam: Critical Concepts in Islamic Studies. Routledge. p. 77. ISBN 978-0415456531.

- ^ a b Pan 1949, 103.

- ^ a b Stone, Martin (1997), The Agony of Algeria, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, p. 29, ISBN 1-85065-177-9.

- ^ Milli Gazete. "Levanten Türkler". Archived from the original on 2010-02-23. Retrieved 2012-03-19.

- ^ Miltoun, Francis (1985), The spell of Algeria and Tunisia, Darf Publishers, p. 129, ISBN 1850770603,

Throughout North Africa, from Oran to Tunis, one encounters everywhere, in the town as in the country, the distinct traits which mark the seven races which make up the native population: the Moors, the Berbers, the Arabs, the Negreos, the Jews, the Turks and the Kouloughlis… descendants of Turks and Arab women.

- ^ Ahmida 2009, 23.

- ^ Kirkpatrick, David D. (2014). "Strife in Libya Could Presage Long Civil War". New York Times. Retrieved 18 September 2019.

- ^ a b Dupree 1958, 41.

- ^ Malcolm & Losleben 2004, 62.

- ^ a b c d Kutlugün, Satuk Buğra (2015). "Osmanlı torunları Libya'da dernek kurdu". Bugun. Retrieved 2016-05-15.

- ^ a b c d Kutlugün, Satuk Buğra (2015). "Osmanlı torunları Libya'da dernek kurdu". Anadolu Agency. Retrieved 2016-05-15.

- ^ a b Pan 1949, 121.

- ^ Sirageldin 2003, 236

- ^ Papademetriou & Martin 1991, 123

- ^ Ergener 2002, 76

- ^ a b Ronen, Yehudit; Yanarocak, Hay Eytan Cohen (2013), "Casting off the shackles of Libya's Arab-Middle Eastern foreign policy: a unique case of rapprochement with non-Arab Turkey (1970s–2011)", The Journal of North African Studies, 18 (3): 499

- ^ a b Ronen & Yanarocak 2013, 501

- ^ Çetin, Nurullah (2014). "Libya'da Türk varlığı". Yeni Mesaj. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- ^ De Giovannangeli, Umberto (2019). "Al-Sarraj vola a Milano per incontrare Salvini, l'uomo forte d'Italia". Huffington Post. Retrieved 26 September 2019.

... Misurata (centro principale della comunità di origine turca in Libia e città-chiave nella determinazione dei nuovi equilibri di potere nel Paese)

- ^ a b Rossi, David (2019). "PERCHÉ NESSUNO PARLA DELLA LIBIA?". Difesa Online. Retrieved 26 September 2019.

Chi conosce appena la situazione demografica di quella parte di Libia sa che Misurata con i suoi 270.000 abitanti (su 400.000) di origine turca e tuttora turcofoni non perderà mai il sostegno di Ankara e non cesserà un attimo di resistere, con o senza Sarraj.

- ^ Muradoğlu, Abdullah (2015). "Kuloğlu'nun ahvâlini sorana." Yeni Şafak. Retrieved 2016-05-15.

- ^ Hasasu, Can (2014). "Kod adı Şakir". Aljazeera. Retrieved 2016-05-16.

- ^ "REPORT ON THE HUMAN RIGHTS SITUATION IN LIBYA" (PDF). Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. 2015. p. 13. Retrieved 27 September 2019.

- ^ يحن لأصوله التركية .. فتحي آغا مؤسس ميليشيات حرق ليبيا, 3thmanly, 2019, retrieved 22 September 2019

- ^ حسني بي: أنا من ضمن المليون تركماني في ليبيا, Alsaaa24, 2019, retrieved 2 January 2020

- ^ Habib, Henry (1981), Libya: Past and Present, Edam Publishing House, p. 42

- ^ Ahmida, Ali Abdullatif (2013), Forgotten Voices: Power and Agency in Colonial and Postcolonial Libya, Routledge, p. 79-80, ISBN 1136784438

- ^ Villard, Henry Serrano (1956), Libya: The New Arab kingdom of North Africa, Cornell University Press, p. 56,

Of the different personalities in the Parliament which took up its duties in 1952, none was so picturesque as Omar Pasha Mansour el Kekhia, President of the Senate. Grand old man of Libya's tenuous political past, Omar Pasha was as proud of his Turkish ancestry as he was of his conjugal successes;

- ^ Alnajjar, Tareq (1956), Who Kidnapped the Former Libyan Minister for Foreign Affairs in Egypt, Libya Watanona, retrieved 22 September 2019

- ^ Hurriyet Daily News. "Turkey's living link to Ottoman Libya: Son of former PM tells father's story". Retrieved 2016-05-15.

- ^ First, R. (1974), Libya: The Elusive Revolution, Africana Publishing Company, p. 115, ISBN 0841902119

- ^ Fawzi, Osama (2007), Arab Times http://www.arabtimes.com/2007/Feb/116.html, retrieved 29 January 2018

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Yeaw, Katrina Elizabeth Anderson (2017), Women, Resitance and the Creation of New Gendered Frontiers in the Making of Modern Libya, 1890-1980, Georgetown University, p. 152

Bibliography

- Ahmida, Ali Abdullatif (2009), The Making of Modern Libya: State Formation, Colonization, and Resistance (Print), Albany, N.Y: SUNY Press, ISBN 1-4384-2891-X.

- Dupree, Louis (1958), "The Non-Arab Ethnic Groups of Libya", Middle East Journal, 12 (1): 33–44

- Ergener, Reşit (2002), About Turkey: Geography, Economy, Politics, Religion, and Culture, Pilgrims Process, ISBN 0-9710609-6-7.

- Fuller, Graham E. (2008), The New Turkish Republic: Turkey as a pivotal state in the Muslim world, US Institute of Peace Press, ISBN 1-60127-019-4.

- Harzig, Christiane; Juteau, Danielle; Schmitt, Irina (2006), The Social Construction of Diversity: Recasting the Master Narrative of Industrial Nations, Berghahn Books, ISBN 1-57181-376-4.

- Koloğlu, Orhan (2007), 500 Years in Turkish-Libyan Relations (PDF), SAM.

- Malcolm, Peter; Losleben, Elizabeth (2004), Libya, Marshall Cavendish, ISBN 0-7614-1702-8.

- Pan, Chia-Lin (1949), "The Population of Libya", Population Studies, 3 (1): 100–125, doi:10.1080/00324728.1949.10416359

- Papademetriou, Demetrios G.; Martin, Philip L. (1991), The Unsettled Relationship: Labor Migration and Economic Development, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 0-313-25463-X.

- Sirageldin, Ismail Abdel-Hamid (2003), Human Capital: Population Economics in the Middle East, American University in Cairo Press, ISBN 977-424-711-6.

- Stone, Martin (1997), The Agony of Algeria, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, ISBN 1-85065-177-9.