Mongol invasions of Vietnam: Difference between revisions

→Background: format refs |

|||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

9781446486153|last1 = Man|first1 = John|date = 2012-03-31}}</ref><br>'''Third invasion (1288):''' Remaining forces from the second invasion,{{br}}Reinforcements: 70,000 Yuan troops, 21,000 tribal auxiliaries, and 500 ships,{{sfn|Atwood|2004|p=579–580}}{{br}}Total: ~170,000–300,000 men<ref>{{Cite book | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=qTDfAQAAQBAJ&pg=PA524&dq=1288+mongol+invasion+vietnam+300,000#q=1288%20mongol%20invasion%20vietnam%20300%2C000 | title=Dictionary of Wars| isbn=9781135954949| last1=Kohn| first1=George Childs| date=2013-10-31}}</ref> |

9781446486153|last1 = Man|first1 = John|date = 2012-03-31}}</ref><br>'''Third invasion (1288):''' Remaining forces from the second invasion,{{br}}Reinforcements: 70,000 Yuan troops, 21,000 tribal auxiliaries, and 500 ships,{{sfn|Atwood|2004|p=579–580}}{{br}}Total: ~170,000–300,000 men<ref>{{Cite book | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=qTDfAQAAQBAJ&pg=PA524&dq=1288+mongol+invasion+vietnam+300,000#q=1288%20mongol%20invasion%20vietnam%20300%2C000 | title=Dictionary of Wars| isbn=9781135954949| last1=Kohn| first1=George Childs| date=2013-10-31}}</ref> |

||

| strength2 = '''Invasion of Champa (1282–1284):'''{{br}}Champa: About 30,000{{sfn|Lo|2012|p=288}}{{br}}'''Second invasion (1285):'''{{br}}Đại Việt: 100,000<ref>{{cite web|title=Tìm hiểu về tổ chức quân đội nhà Trần trong chiến tranh chống quân Nguyên xâm lược|url=http://bienphongvietnam.vn/lich-su-van-hoa/dlls/2013-ddd.html|publisher=[[Vietnam Border Defence Force]]|accessdate=19 September 2018|language=vi|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20190613210635/http://bienphongvietnam.vn/lich-su-van-hoa/dlls/2013-ddd.html |archivedate=2019-06-13}}</ref>{{better source|date=September 2020}} |

| strength2 = '''Invasion of Champa (1282–1284):'''{{br}}Champa: About 30,000{{sfn|Lo|2012|p=288}}{{br}}'''Second invasion (1285):'''{{br}}Đại Việt: 100,000<ref>{{cite web|title=Tìm hiểu về tổ chức quân đội nhà Trần trong chiến tranh chống quân Nguyên xâm lược|url=http://bienphongvietnam.vn/lich-su-van-hoa/dlls/2013-ddd.html|publisher=[[Vietnam Border Defence Force]]|accessdate=19 September 2018|language=vi|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20190613210635/http://bienphongvietnam.vn/lich-su-van-hoa/dlls/2013-ddd.html |archivedate=2019-06-13}}</ref>{{better source|date=September 2020}} |

||

| casualties1 = |

| casualties1 = Slightly light in 1258, heavy in 1285 and heavy in 1288. |

||

| casualties2 = Unknown |

| casualties2 = Unknown |

||

}} |

}} |

||

Revision as of 03:14, 5 November 2020

| Mongol invasions of Đại Việt and Champa | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Mongol invasions | |||||||

| File:Battle of Bach Dang (1288).jpg The Battle of Bạch Đằng (1288) during the Third Mongol invasion | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

Champa | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

Jaya Indravarman VI Indravarman V Prince Harijit | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

First invasion (1258): ~3,000 Mongols and 10,000 Yi people (Western estimate)[2] ~30,000 Mongols and 20,000 Yi people (Vietnamese estimate)[3] Second invasion (1285): ~80,000-300,000 (some speak of 500,000) in March 1285[4][5] Third invasion (1288): Remaining forces from the second invasion, Reinforcements: 70,000 Yuan troops, 21,000 tribal auxiliaries, and 500 ships,[6] Total: ~170,000–300,000 men[7] |

Invasion of Champa (1282–1284): Champa: About 30,000[8] Second invasion (1285): Đại Việt: 100,000[9][better source needed] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Slightly light in 1258, heavy in 1285 and heavy in 1288. | Unknown | ||||||

The Mongol invasions of Vietnam or Mongol-Vietnamese Wars were military campaigns launched by the Mongol Empire, and later the Yuan dynasty, against the kingdom of Đại Việt ruling by Trần dynasty (modern-day northern Vietnam) and the Champa (modern-day southern Vietnam) in 1258, 1282–1284, 1285, and 1287–88. In studies of China and Mongolia, the campaigns are often treated as a success due to the establishment of tributary relations with Đại Việt despite the Mongols suffering several military defeats.[10]: 17 [11]: 212 [12]: 285 In contrast, Vietnamese historiography emphasizes the Dai Viet military victories.[10]: 17

The first invasion began in 1258 under the united Mongol Empire, as it looked for alternative paths to invade Song China. The Mongol general Uriyangkhadai was successful in capturing the Vietnamese capital Thang Long (modern-day Hanoi) before turning north in 1259 to invade the Song dynasty in modern-day Guangxi as part of a coordinated Mongol attack with armies attacking in Sichuan under Möngke Khan and other Mongol armies attacking in modern-day Shandong and Henan.[13] The first invasion also established tributary relations between the Vietnamese kingdom, formerly a Song dynasty tributary state, and the Yuan dynasty. In 1282, Kublai Khan and the Yuan dynasty launched a naval invasion of Champa that also resulted in the establishment of tributary relations.

Intending to demand greater tribute and direct Yuan oversight of local affairs in Đại Việt and Champa, the Yuan launched another invasion in 1285. The second invasion of Đại Việt failed to accomplish its goals, and the Yuan launched a third invasion in 1287 with the intent of replacing the uncooperative Đại Việt ruler Trần Nhân Tông with the defected Trần prince Trần Ích Tắc. By the end of the second and third invasions, which involved both initial successes and large losses for the Mongols, the Đại Việt and Champa decided to accept the nominal supremacy of the Yuan dynasty and serve as tributary states in order to avoid further conflicts.[14][10]

Background

By the 1250s, the Mongol Empire controlled large amounts of Eurasia including much of Eastern Europe, Anatolia, North China, Mongolia, Manchuria, Central Asia, Tibet and Southwest Asia. Möngke Khan (r. 1251–59) planned to attack the Song dynasty in southern China from three directions in 1259. Therefore, he ordered the prince Kublai to pacify the Dali Kingdom. Uriyangkhadai led successful campaigns in the southwest of China and pacified tribes in Tibet before turning east towards Đại Việt by 1257.[15]

In the autumn of 1257, Uriyangkhadai addressed three letters to Vietnamese ruler Trần Thái Tông (known as Trần Nhật Cảnh by the Mongol) demanding passage through to southern China.[16] Trần Thái Tông opposed the encroachment of a foreign army across his territory to attack their ally, and so prepared soldiers on elephants to deter the Mongol troops.[10] After the three successive envoys were imprisoned in the capital Thang Long (modern-day Hanoi) of Đại Việt, Uriyangkhadai invaded Đại Việt with generals Trechecdu and Aju in the rear.[16][2]

Đại Việt at the time was a flourishing Buddhist kingdom in Southeast Asia, maintaining diplomat and trade contacts with the Song dynasty, the Dali kingdom and many kingdoms in Southeast Asia.[17] The ancestors of the Trần clan originated from the province of Fujian and later migrated to Đại Việt under Trần Kinh 陳京 (Chén Jīng), the ancestor of the Trần clan in 1127. Their descendants, the later rulers of Đại Việt who were of mixed-blooded descent later replaced the house of Lý, established the Trần dynasty in 1226, which ruled Vietnam (Đại Việt); despite many intermarriages between the Trần and several royal members of the Lý royals alongside members of their royal court as in the case of Trần Lý[18][19]Template:Better source inline and Trần Thừa,[20] some of the mixed-blooded descendants of the Trần dynasty and certain members of the clan could still speak Chinese such as when a Yuan dynasty envoy had a meeting with the Chinese-speaking Trần prince Trần Quốc Tuấn in 1282.[21][22][23][24][25][26] The Champa kingdom was a close neighbor of Đại Việt since early 10th century. The kingdom was brief occupied by the Khmer Empire in the west in early 13th century. Facing the Mongol threats, Chams and Vietnamese formed an alliance fought together against the Mongols.[27]

Historian Liam Kelley noted that people from Song dynasty China like Zhao Zhong and Xu Zongdao escaped to Đại Việt after the Mongol invasion of the Song and helped the Vietnamese fight against the Mongol invasion. The ancestors of the Trần clan originated from the Fujian region of China as did the Daoist Chinese cleric Xu Zongdao who recorded the Mongol invasion and referred to them as "Northern bandits". He quoted the Đại Việt Sử Ký Toàn Thư which said "When the Song [Dynasty] was lost, its people came to us. Nhật Duật took them in. There was Zhao Zhong who served as his personal guard. Therefore, among the accomplishments in defeating the Yuan [i.e., Mongols], Nhật Duật had the most."[28][29]

Southern Song Chinese military officers and civilian officials left to overseas countries, went to Vietnam and intermarried with the Vietnamese ruling elite and went to Champa to serve the government there as recorded by Zheng Sixiao.[30] Southern Song soldiers were part of the Vietnamese army prepared by king Trần Thánh Tông against the second Mongol invasion.[31]

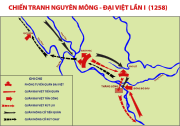

First Mongol invasion in 1258

Mongol forces

In 1258, a Mongol column under Uriyangkhadai, the son of Subutai, invaded Đại Việt. According to Vietnamese sources, the Mongol army consisted of at least 30,000 soldiers of which at least 2,000 were Yi troops from the Dali Kingdom.[3] Modern scholarship points to a force of several thousand Mongols, ordered by Kublai to invade with Uriyangkhadai in command, which battled with the Viet forces on 17 January 1258.[32] Some Western sources estimated that the Mongol army consisted of about 3,000 Mongols with an additional 10,000 Yi soldiers.[2]

Campaign

A battle was fought in which the Vietnamese used war elephants: king Trần Thái Tông even led his army from atop an elephant.[33] Aju ordered his troops to fire arrows at the elephants' feet.[33][10] The animals turned in panic and caused disorder in the Vietnamese army, which was routed.[33][10] The Vietnamese senior leaders were able to escape on pre-prepared boats while part of their army was destroyed at No Nguyen (modern Viet Tri on the Hong River). The remainder of the Dai Viet army again suffered a major defeat in a fierce battle at the Phú Lộ bridge the day after. This led the Vietnamese monarch to evacuate the capital. The Đại Việt annals reported that the evacuation was "in an orderly manner;" however this is viewed as a embellishment because the Vietnamese had to retreat in disarray to leave their weapons behind in the capital.[33]

King Trần Thái Tông fled to an offshore island,[34] while the Mongols occupied the capital city Thăng Long (modern-day Hanoi). They found their envoys in prison, however one of whom died. In revenge, Mongols massacred the city's inhabitants.[35] Although the Mongols had successfully captured the capital, the provinces around the capital were still under Vietnamese control.[36]: 85 While Chinese source material is sometimes misinterpreted as saying that Uriyangkhadai withdrew from Vietnam due to poor climate,[37][13] Uriyangkhadai left Thang Long after nine days to invade the Song dynasty in modern-day Guangxi in a coordinated Mongol attack with armies attacking in Sichuan under Möngke Khan and other Mongol armies attacking in modern-day Shandong and Henan.[13] The Mongol army gained the popular local nickname of "Buddhist enemies" because they did not loot nor kill while moving north out to Yunnan.[36] After the loss of a prince and the capital, Trần Thái Tông submitted to the Mongols.[10]

In 1258, the Vietnamese monarch Trần Thái Tông commenced regular diplomatic relations and a tributary relationship with the Mongol court, treating them as equals to the embattled Southern Song dynasty without renouncing their ties to the Song.[10] In March 1258, Trần Thái Tông retired and let his son, prince Trần Hoảng succeed the throne. In the same year, the new king sent envoys to the Mongol in Yunnan. The Mongol leader Uriyangkhadai demanded the king must came to China to submit in person. King Trần Thánh Tông answer: "If my small country sincerely serves your majesty, how will your big country treat us?" The Mongol envoys traveled back to Thăng Long, Yunnan and Dadu, eventually the message from the Vietnamese court was the king's children or brother would be sent to China as hostage.[35]

Invasion of Champa in 1282

With the defeat of the Song dynasty in 1276, the newly established Yuan dynasty turned its attention to the south, particularly Champa and Đại Việt.[38] In late 1281, Kublai decided to make Champa to be a new province of the Yuan Empire, and announced the invasion of Champa.[38] Sogetu of the Jalairs, the governor of Guangzhou, was dispatched to demand the submission of Champa. Although the king of Champa accepted the status of a Mongol protectorate,[39] his submission was unwilling. Kublai knew that the pro-Song sentiment was strong in Champa, the Cham king was had been sympathetic to the Song cause.[40] A large numbers of Chinese officials, soldiers and civilians who fled from the Mongol had refuge in Champa, and they had inspired and incited to hate the Mongol.[41] Thus, in the summer of 1282, when Yuan envoys He Zizhi, Hangfu Jie, Yu Yongxian, and Yilan passed through Champa, they were detained and imprisoned by the Cham Prince Harijit.[41] In March 1282, Sogetu led a maritime invasion of Champa with 5,000 men, but could only muster 100 ships and 250 landing crafts because most of the Yuan ships had been lost in the invasions of Japan.[42]

Sogetu's fleet arrived in Champa's shore, near modern day Thị Nại Bay in February 1283.[43] The Cham defenders had already prepared a fortified wooden palisades in the west shore of the bay.[41] The Mongol landed at midnight of 13 February with 4,900 soldiers, attacked the stockade by three sides. The Cham defenders opened the gate, marched to the beach and met the Yuan with 10,000 men and several scores of elephants.[8] The Cham deployed 100 counterweight trebuchets (hui hui pao 回回砲).[43] Undaunted, the highly experienced Mongol general selected points of attack and launched so fierce an assault that they broke through then initial defeated the Chams.[43] Sogetu's forces arrived the capital Vijaya and captured the city two days later, but then withdrew and set up camps outside the city.[8] The aged Champa king Indravarman V retreated out of the capital, avoiding Mongol attempts to capture him in the hills. The Cham king and his prince Harijit both refused to visit the Mongol camp. The Cham executed two Mongol envoys and ambushed Sogetu's troops in the mountains.[8] His son would wage guerrilla warfare against the Mongols for the next two years, eventually wearing down the invaders.[44] From a captured spy, Sogetu knew that Indravarman had 20,000 men with him in the mountains, he had summoned Cham reinforcements from Panduranga in the south, and also dispatched emissaries to Đại Việt, Khmer Empire and Java for seeking aid.[8]

Stymied by the withdrawal of the Champa king, Sogetu asked for reinforcements from Kublai. The Mongols withdrew to the wooden stockade on the beach in order to await reinforcements and supplies. Sogetu's men unloaded the supplies, cleared the field for farming rice.[45] Sogetu sent two officers to Cambodia to open relations with that country, but they were detained.[45] In March 1284 another Mongol fleet with more than 20,000 troops of 200 ships under Ataqai and Arigh Khaiya embarked on a fruitless mission to reinforce him.[45] Sogetu presented his plan to have more troops invade Champa through Đại Việt. Kublai accepted his plan and put his son Toghan in command, with Sogetu as second in command.[45]

Second Mongol invasion in 1285

Background and diplomacy

In 1266, the Vietnamese monarch Trần Thánh Tông (son of Trần Thái Tông - known to the Mongols as Trần Nhật Huyên) agreed in 1266 to acknowledge the overlordship of Kublai Khan, however in the following year, he rejected the "Six-Duties of a vassal state" of the Mongol Emperor gave, included the permit the stationing of a darughachi (regional general) with authority over the local administration.[34] Kublai Khan was dissatisfied with the tributary arrangement, which granted the Yuan dynasty the same amount of tribute as the former Song dynasty had received, and requested greater tributary payments.[10]: 19 These demands included taxes to the Mongols in both money and labor, "incense, gold, silver, cinnabar, agarwood, sandalwood, ivory, tortoiseshell, pearls, rhinoceros horn, silk floss, and porcelain cups".[10]: 19 Later that year, Kublai required Đại Việt to send two Muslim merchants he believed to be there to China to order for them to serve on missions on the Western regions and designated heir apparent of the Yuan as "Prince of Yunnan" to take control of Dali, Shanshan (Kunming) and Đại Việt, this mean Đại Việt should be incorporated into the Yuan Empire, which was totally unacceptable to the Vietnamese.[47]

In 1268, the Yuan court sent Hulonghaiya to Vietnamese capital to replaced Nanladin as overseer of Annam with his assistant Zhang Tingzhen. The next year Zhang replaced Hulonghaiya as overseer while holding the prestigious title of Grant Master for the Court Precedence. Arriving the Vietnamese capital Thăng Long, Zhang delivered Kublai Khan's edict, but king Thánh Tông stood (rather than kowtowed) to received it.[48] Zhang upset accused the king of maintaining connections with the Song dynasty in Southern China, and threatened him with Yuan military forces - a million Yuan troops were besieging Xiangyang "could reach Đại Việt" in less than two months. According to Chinese sources, this scared the Vietnamese king and made he kowtow to the edict.[48] The king nonetheless had more complaints which can be seen in his dialogue with Zhang.[48] After few sentences, Trần Thánh Tông felt increasingly angry. Hence he ordered guards draw their swords and surround Zhang to threaten him. Seeing this, Zhang untied his bow and sword and lay them down on the floor in middle of the hall, saying: "See what you can do to me!". The Vietnamese king and his guards were impressed with Zhang's courage.[48] In 1269, Trần Thánh Tông memorialized the Yuan court that the two Muslim merchants had died, so he would send two large elephants demanded by Huilonghaiya in the proper tribute year.[49] In the next year, the Secretariat of the Yuan sent to the Vietnamese king a message, quoting the words from the Spring and Autumn Annals to chastise him for not "having kowtowed to the imperial edict; for having treated the emissary of the Son of Heaven (Kublai) improperly; for having presented bad-tasting medicine, and for having dishonest in the matter of the Muslim merchants." Trần Thánh Tông refused these accusations in his letter written in Classical Chinese to Kublai next year (1271).[49] In next two years, Kublai sent new overseers to Đại Việt, demanded for searching the lost copper columns of Ma Yuan which erected after the Trung sisters' rebellion was suppressed in 43 AD, and one again wanted Trần Thánh Tông to be presented in Dadu by person. He refused.[50]

In 1278, Trần Thái Tông died, the king Trần Thánh Tông retired and made crown prince Trần Khâm (as known as Trần Nhân Tông, known to the Mongol as Trần Nhật Tôn) as the successor. Kublai sent a mission led by Chai Chun to Đại Việt, one again urged the new king to come to China in person, however the Yuan mission ended in failures as the king resisted to go.[51] Frustrated with these failed diplomat missions, many Yuan officials urged Kublai to send a punitive expedition to Đại Việt.[52] In 1283, Khubilai Khan sent word to Đại Việt that he intended to send Yuan armies through Vietnamese territory to attack the kingdom of Champa, with demands for provisions and other support to the Yuan army.[10]: 19

In 1284 Kublai appointed his son Toghan (Vietnamese: Thoát Hoan) to conquer Champa. Toghan demanded from the Vietnamese a route to Champa, which would trap the Champan army from both north and south. While Thánh Tông and Nhân Tông initially accepted the demand reluctantly, then denied,[53] and ordered an defensive war against the Mongol army.[10][54] A Yuan envoy recorded that the Vietnamese had already sent 500 ships to help the Cham.[53] As the Mongol invasion was imminent, in 1284, king Nhân Tông held the All-Vietnamese Conference of Diên Hồng (Vietnamese: Hội Nghị Diên Hồng), with the participation of all nobles and officials.[55] All members of the Conference agreed to resist the Mongol invasion rather than accept the "darughachi" system. The king ordered all regulars and military to tattoo on their hands two words "Sát Thát" (殺韃, death to the Tatars). [55][53]

Campaign

The main Yuan army led by Toghon was said in History of Yuan to consist of 8 tumens, with some 20,000 unarmed Jurchen and Han Chinese supporters, and many Yuan veterans such as Ariq Qaya (Uyghur), Li Heng (Tangut), Bolqadar, and Mangqudai.[46][56] Yuan troops crossed the Friendship Pass (Sino-Vietnamese border's gate) on 27 January 1285.[57] After passed the mountainous terrains with collecting nails, traps along the highway, Mongol forces captured 400 Song officers who were fighting alongside with the Vietnamese.[56] In the Red River Delta, the combined Yuan land forces attacked the Vietnamese forces by land and river, destroyed several Vietnamese catapults (Hu dun pao) along the Red River, successful captured Đại Việt's capital Thăng Long and drove the Vietnamese forces and the Royal family to the coast.[56] Many Vietnamese royals and nobles were frightened and defected to the Yuan, including prince Trần Ích Tắc.[58]

Planning to weaken the enemies first, the Vietnamese royal family abandoned the capital and retreated south while enacting a scorched earth campaign by abandoning empty capital and cities, burning villages and crops where the Mongols occupied.[44] At the same time, Sogetu moved his army up north in an attempt to envelop the Vietnamese royal family in a pincer movement,[44] but King Nhân Tông and his army managed to escape to Nam Định, and re-concentrated here.[54] The king tried to prevent Sogetu from linking with Toghon, but failed and forced royal family retreated to the coastal Quảng Ninh province.[59] The Yuan forces under Omar launched two naval offensives in April and again drove the Vietnamese forces to the south.[56] In the same month, while the Vietnamese expressed their willingness to negotiate, the Yuan side said to the Vietnamese king Trần Nhân Tông: "Since [you] want peace, but don't you come in person?" The king did not listen.[60] The Vietnamese forces under prince Trần Quốc Tuấn continued to resist, employed guerrilla tactics to deprive the Mongol supplies.[58] In a skirmish in Hàm Tử pass (modern day Khoái Châu District, Hưng Yên) in May 1285, a contingent of Yuan troops was defeated by a partisan force consisting of former Song troops and native militia.[58]

Sogetu's army was weakened by the summer heat and the lack of food, so they stopped chasing the royal family and move north to join with Toghan. Seeing the Mongols’ movement, prince Quốc Tuấn concluded that the Mongol army was weakened and decided to take the opportunity to strike, selecting battlefields where the Mongol cavalry could not be fully employed.[61] In May 1285, situation began changing as Yuan's supplies running low.[56] Take avdantage, a Vietnamese fleet under prince Trần Quốc Tuấn sailed to the north and attacked Vạn Kiếp, the important Mongol camp and cut off the Mongol supplies.[59][62] Many Yuan generals were killed in the battle, included the senior Li Heng who was struck by poisoned arrow.[63] The Cham were in pursuit of Sogetu as he was heading north,[64] and killed him and defeated his army.[61][63] As the Yuan forces bogged down in the Red River delta, dispersing their power, Duke Trần Quang Khải personally launched a large counterattack at Chương Dương and Vạn Kiếp, forcing Toghan to withdraw. Toghan returned without a huge loss of the army under him thanks to the Kipchak officer Sidor and his navy.[37]: 9 The Yuan remnants retreated back to China on June 9, 1285.[62]

Third Mongol invasion, 1287-88

Background and preparations

In 1286, Kublai Khan appointed Trần Thánh Tông's younger brother, Prince Trần Ích Tắc, as the King of Đại Việt from afar with the intent of dealing with the uncooperative incumbent Trần Nhân Tông.[10]: 24 [65] Trần Ích Tắc, who had already surrendered to the Yuan, was willing to lead a Yuan army into Đại Việt to take the throne.[10]: 24 Kublai Khan cancelled plans underway for a third invasion of Japan to concentrated miltary preparations in the south.[66] Kublai accused the Vietnamese for raiding China, and pressed the efforts of China should be directed towards winning the war against Đại Việt.[67]

In October 1287, the Yuan land forces commanded by Toghon moved southwards from Guangxi and Yunnan in three divisions led by general Abachi and Changyu,[68] while the naval expedition led by generals Omar, Zhang Wenhu, and Aoluchi.[10]: 24 The army was complemented by a large naval force that advanced from Qinzhou, with the intent to form a large pincer movement against the Vietnamese.[10]: 24 The force was composed of Mongols, Jurchen, Han Chinese, Zhuang, and Li troops.[10]: 24 [68] Total Yuan forces raised up to 170,000 men for this invasion.[63]

Campaign

The Yuan were successful in the early phases of the invasion, occupying and looting the Đại Việt capital.[10]: 24

In January 1288, as Omar's fleet passed through the Ha Long Bay, followed by Zhang Wenhu's supply fleet, the Vietnamese navy under prince Trần Khánh Dư attacked and destroyed Wenhu's fleet.[10]: 26 [66] The Yuan land army under Toghan and naval fleet under Omar, both already in Vạn Kiếp (today Hải Dương province), were unaware of the loss of their supply fleet.[10]: 26 Toghon returned back to the capital Thăng Long to loot food, while Omar destroying king Trần Thái Tông's tomb in Thái Bình.[66]

Due to a lack of food supplies, Toghon and Omar's army retreated from Thăng Long to their fortified main base in Vạn Kiếp (northeast of Hanoi) on 5 March 1288. [69] They planned to withdraw from Đại Việt but waited for the supplies to arrive before departing.[10]: 26 As food supplies ran low and their positions became untenable, Toghon decided on 30 March 1288 to return to China.[69] Toghon boarded a large warship for himself and the Yuan land force could not withdraw in the same way from which they came. Trần Hưng Đạo, aware of the Yuan retreat, prepared to attack. The Vietnamese had destroyed bridges, roads and creating traps along the retreating Yuan route. They pursued Toghon's forces to Lạng Sơn, where on April 10,[70] Toghon was forced to abandoned his ship, avoided highway and was escorted back to China by his few remaining troops through the forests.[70] Most of Toghon's land force were killed or captured.[70] Meanwhile, the Yuan fleet commanded by Omar were retreating through the Bạch Đằng river.[69]

At the Bạch Đằng River in April 1288, the Vietnamese prince Trần Hưng Đạo ambushed Omar's Yuan fleet in the third Battle of Bạch Đằng.[10]: 24 The Vietnamese forces placed hidden metal-tipped wooden stakes in the riverbed and attacked the fleet once it had been impaled on the stakes.[10]: 26 Omar himself was taken as a prisoner of war.[66][70] The Yuan fleet was destroyed and the army retreated in disarray without supplies.[10]: 26 Few days later, Zhang Wenhu who thought that the Yuan armies still in Vạn Kiếp, unaware of the Yuan defeat, his transport fleet sailed into the Bạch Đằng river and was destroyed by the Vietnamese navy.[70] Only Wenhu and few Yuan soldiers managed to escaped.[70]

In 1288, the Yuan army engaged the Vietnamese army at the Thái Bình River in a battle during which Toghan was struck by a poisoned arrow.[10]: 24 Several thousand Yuan troops, unfamiliar with the terrain, were lost and never regained contact with the main force.[10]: 24 An account of the battle from Lê Tắc, a Vietnamese scholar who defected to the Yuan in 1285, said that the remnants of the army followed him north in retreat and reached Yuan-controlled territory on Lunar New Year's Day in 1289.[10]: 24 After three further months in Đại Việt, the Yuan army were withdrawn before malaria season.[10]: 25

Aftermath

Yuan

Kublai was angry over the Yuan defeats in Đại Việt and wanted to launch another invasion, but was persuaded in 1291 to sent the Minister of Rites Zhang Lidao to induce Trần Nhân Tông to come. The Yuan mission arrived to Vietnamese capital on 18 March 1292 and stay in a guesthouse, where the king made a protocol with Zhang.[71] Trần Nhân Tông sent a mission with a memorial to return with Zhang Lidao to China. In memorial, Trần Nhân Tông explained his inability to visit China. The detail said among ten Vietnamese envoys to Dadu, six or seven of them died on the way.[72] Instead of going to Dadu personally by himself, the Vietnamese king sent a gold statue to Yuan court.[70] Another Yuan mission was sent in September 1292.[72] As late as 1293, Kublai Khan planned a fourth military campaign to install Trần Ích Tắc as the King of Đại Việt, but the plans for the campaign were halted when Kublai Khan died in early 1294.[10]: 25 The new Yuan emperor, Temür Khan announced that the war with Đại Việt was over, and he sent a mission to Đại Việt to restore friendly relations between two countries.[73]

Đại Việt

Three Mongol invasions devastated Đại Việt severely, but the Vietnamese did not succumb to Yuan demands. Eventually not a single Trần king or prince visited China.[74] The Trần monarchs of Đại Việt decided to accept the supremacy of the Yuan dynasty in order to avoid further conflicts. In 1289, Đại Việt released most of Mongol prisoners of war back to China, but Omar, whose return Kublai particularly demanded, was intentionally drowned when the boat transporting him was contrived to sink.[66] In the winter of 1289–1290, the Trần ruler Trần Nhân Tông led an attack into modern-day Laos, against the advice of his advisors, with the goal of preventing raids from the inhabitants of the highlands.[75] Famines and starvations ravaged the country from 1290 to 1292. There were no records of what caused the crop failures, but possible factors included neglect of the water control system due to the war, the mobilization of men away from the rice fields, and floods or drought.[75]

In 1293, Kublai detained the Vietnamese envoy, Đào Tử Kí, because Trần Nhân Tông refused to go to Beijing in person. Kublai's successor Temür Khan (r.1294-1307), later released all detained envoys and resumed their tributary relationship initially established after the first invasion, which continued to the end of the Yuan.[14]

The The Travels of Marco Polo describes Marco Polo's 1288 visit to Đại Việt:

Caugigu [Giao Chỉ][a] is a province towards the east, which has a king. The people are Idolaters, and have a language of their own. They have made their submission to the Great Kaan, and send him tribute every year. And let me tell you their king is so given to luxury that he hath at the least 300 wives; for whenever he hears of any beautiful woman in the land, he takes and marries her.

They find in this country a good deal of gold, and they also have great abundance of spices. But they are such a long way from the sea that the products are of little value, and thus their price is low. They have elephants in great numbers, and other cattle of sundry kinds, and plenty of game.They live on flesh and milk and rice, and have wine made of rice and good spices. The whole of the people, or nearly so, have their skin marked with the needle in patterns representing lions, dragons, birds, and what not, done in such a way that it can never be obliterated. This work they cause to be wrought over face and neck and chest, arms and hands, and belly, and, in short, the whole body; and they look on it as a token of elegance, so that those who have the largest amount of this embroidery are regarded with the greatest admiration.[77]

Champa

The Champa Kingdom decided to accept the supremacy of the Yuan dynasty and also established a tributary relationship with the Yuan.[14] In 1305, Cham king Chế Mân (r. 1288 – 1307) got married with Vietnamese princess Huyền Trân (daughter of Trần Nhân Tông) as him ceded two provinces Ô and Lý to Đại Việt.[78]

Legacy

Despite the military defeats suffered during the campaigns, they are often treated as a success by historians for the Mongols due to the establishment of tributary relations with Đại Việt and Champa.[10]: 17 [11]: 212 [12]: 285 The initial Mongol goal of placing Đại Việt, a tributary state of the Southern Song dynasty, as their own tributary state was accomplished after the first invasion.[10]: 17 However, the Mongols failed to impose their demands of greater tribute and direct darughachi oversight over Đại Việt's internal affairs during their second invasion and their goal of replacing the uncooperative Trần Nhân Tông with Trần Ích Tắc as the King of Đại Việt during the third invasion.[10]: 19 [10]: 24 Nonetheless, friendly relations were established and Dai Viet continued to pay tribute to the Mongol court.[79][80]

Vietnamese historiography emphasizes the Vietnamese military victories.[10]: 17 The three invasions, and the Battle of Bạch Đằng in particular, are remembered within Vietnam and Vietnamese historiography as prototypical examples of Vietnamese resistance against foreign aggression.[10]: 19 [16]

Notes

References

- ^ Anderson & Whitmore 2014, p. 129.

- ^ a b c Atwood 2004, p. 579.

- ^ a b Hà, Văn Tấn; Phạm, Thị Tâm (2003). "III: Cuộc kháng chiến lần thứ nhất" [III: The First Resistance War]. Cuộc kháng chiến chống xâm lược Nguyên Mông thế kỉ XIII [The resistance against the Mongol invasion in the 13th century] (in Vietnamese). People's Army Publishing House. pp. 66–88.

- ^ Man, John (2012-03-31). Kublai Khan. ISBN 9781446486153.

- ^ Man, John (2012-03-31). Kublai Khan. ISBN 9781446486153.

- ^ Atwood 2004, p. 579–580.

- ^ Kohn, George Childs (2013-10-31). Dictionary of Wars. ISBN 9781135954949.

- ^ a b c d e Lo 2012, p. 288.

- ^ "Tìm hiểu về tổ chức quân đội nhà Trần trong chiến tranh chống quân Nguyên xâm lược" (in Vietnamese). Vietnam Border Defence Force. Archived from the original on 2019-06-13. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai Baldanza, Kathlene (2016). Ming China and Vietnam: Negotiating Borders in Early Modern Asia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9781316440551.004. ISBN 978-1-316-44055-1.

- ^ a b Weatherford, Jack (2004). Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World. Three Rivers Press.

- ^ a b Hucker, Charles O. (1975). China's Imperial Past: An Introduction to Chinese History and Culture. Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804723534.

- ^ a b c Haw, Stephen G. (2013). "The deaths of two Khaghans: a comparison of events in 1242 and 1260". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. 76 (3): 361–371. doi:10.1017/S0041977X13000475. JSTOR 24692275.

- ^ a b c Bulliet, Richard; Crossley, Pamela; Headrick, Daniel; Hirsch, Steven; Johnson, Lyman (2014-01-01). The Earth and Its Peoples: A Global History. Cengage Learning. ISBN 9781285965703.

- ^ Rossabi 2009, p. 27.

- ^ a b c Lien, Vu Hong; Sharrock, Peter (2014). "The First Mongol Invasion (1257-8 CE)". Descending Dragon, Rising Tiger: A History of Vietnam. Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1780233888.

- ^ Lammerts 2015, p. 286.

- ^ "Ham sắc, Tô Trung Từ tự hại mình". Retrieved 2017-03-09.

- ^ "Nhà Trần khởi nghiệp". Retrieved 2016-03-09.

- ^ Chapuis 1995, p. 85.

- ^ Taylor 2013, p. 120.

- ^ Hall 2008, p. 159.

- ^ Dutton, Werner & Whitmore 2012, p. 29.

- ^ Gunn 2011, p. 121.

- ^ Embree & Lewis 1988, p. 190.

- ^ Woodside 1971, p. 8.

- ^ Walker 2012, p. 241.

- ^ Kelley, Liam (4 December 2015). "Giặc Bắc đến xâm lược!: Translations and Exclamation Points". Le Minh Khai's SEAsian History Blog. Archived from the original on 2016-10-06. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ^ "Liam Kelley". University of Hawaii at Manoa Department of History. Archived from the original on 14 October 2014.

he maintains a blog on Southeast Asian history called Le Minh Khai's SEAsian History Blog.

- ^ Anderson & Whitmore 2014, p. 122.

- ^ Anderson & Whitmore 2014, p. 124.

- ^ Anderson & Whitmore 2014, p. 121.

- ^ a b c d Descending Dragon, Rising Tiger: A History of Vietnam by Vu Hong Lien, Peter Sharrock, Chapter 6.

- ^ a b Lo 2012, p. 284.

- ^ a b Anderson & Whitmore 2014, p. 207.

- ^ a b Vu, Hong Lien; Sharrock, Peter (2014). Descending Dragon, Rising Tiger: A History of Vietnam. Reaktion Books.

- ^ a b Buell, P.D. "Mongols in Vietnam: end of one era, beginning of another". First Congress of the Asian Association of World Historians 29–31 May 2009 Osaka University Nakanoshima-Center.

- ^ a b Lo 2012, p. 285.

- ^ Grousset 1970, p. 290.

- ^ Lo 2012, p. 286.

- ^ a b c Lo 2012, p. 287.

- ^ Delgado 2008, p. 158.

- ^ a b c Purton 2010, p. 201.

- ^ a b c Delgado 2008, p. 159.

- ^ a b c d Lo 2012, p. 289.

- ^ a b History of the Yuan Dynasty, vol. 209

- ^ Anderson & Whitmore 2014, p. 208.

- ^ a b c d Anderson & Whitmore 2014, p. 209.

- ^ a b Anderson & Whitmore 2014, p. 210.

- ^ Anderson & Whitmore 2014, p. 211.

- ^ Anderson & Whitmore 2014, p. 212.

- ^ Anderson & Whitmore 2014, p. 213.

- ^ a b c Lo 2012, p. 291.

- ^ a b Taylor 2013, p. 133.

- ^ a b Taylor 2013, p. 132.

- ^ a b c d e Lo 2012, p. 293.

- ^ Lo 2012, p. 292.

- ^ a b c Anderson & Whitmore 2014, p. 126.

- ^ a b Taylor 2013, p. 134.

- ^ Anderson & Whitmore 2014, p. 217.

- ^ a b Delgado 2008, p. 160.

- ^ a b Lo 2012, p. 294.

- ^ a b c Anderson & Whitmore 2014, p. 127.

- ^ Stone 2017, p. 76.

- ^ Lo 2012, p. 296.

- ^ a b c d e Taylor 2013, p. 136.

- ^ Lo 2012, p. 281.

- ^ a b Lo 2012, p. 297.

- ^ a b c Lo 2012, p. 301.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lo 2012, p. 302.

- ^ Anderson & Whitmore 2014, p. 221.

- ^ a b Anderson & Whitmore 2014, p. 223.

- ^ Lo 2012, p. 303.

- ^ Anderson & Whitmore 2014, p. 227.

- ^ a b Taylor 2013, p. 137.

- ^ Harris 2008, p. 354.

- ^ The Travels of Marco Polo, chapter 56.

- ^ Aymonier 1893, p. 369.

- ^ Simons 1998, p. 53.

- ^ Walker 2012, p. 242.

Sources

- Atwood, Christopher Pratt (2004). Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire. New York: Facts of File. ISBN 978-0-8160-4671-3.

- Anderson, James A.; Whitmore, John K., eds. (2014). China's Encounters on the South and Southwest: Reforging the Fiery Frontier Over Two Millennia. Brill Publishers. ISBN 978-90-04-28248-3.

- Baldanza, Kathlene (2016). Ming China and Vietnam: Negotiating Borders in Early Modern Asia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781316531310.

- Rossabi, Morris (2009). Khubilai Khan: His Life and Times. University of California Press . ISBN 978-0520261327.

- Connolly, Peter; Gillingham, John; Lazenby, John, eds. (1998). The Hutchinson Dictionary of Ancient & Medieval Warfare. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-57958-116-9.

- Embree, Ainslie Thomas; Lewis, Robin Jeanne (1988). Encyclopedia of Asian history. Scribner. ISBN 9780684189017.

- Chapuis, Oscar (1995). A history of Vietnam: from Hong Bang to Tu Duc. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-313-29622-7.

- Lammerts, Dietrich Christian, ed. (2015). Buddhist Dynamics in Premodern and Early Modern Southeast Asia. ISEAS Publishing, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 9789814519069.

- Gunn, Geoffrey C. (2011). History Without Borders: The Making of an Asian World Region, 1000-1800. Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 978-988-8083-34-3.

- Woodside, Alexander (1971). Vietnam and the Chinese Model: A Comparative Study of Vietnamese and Chinese Government in the First Half of the Nineteenth Century. Harvard Univ Asia Center. ISBN 978-0-674-93721-5.

- Delgado, James P. (2008). Khubilai Khan's Lost Fleet: In Search of a Legendary Armada. Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre. ISBN 978-0-520-25976-8..

- Lo, Jung-pang (2012). Elleman, Bruce A. (ed.). China as a Sea Power, 1127-1368: A Preliminary Survey of the Maritime Expansion and Naval Exploits of the Chinese People During the Southern Song and Yuan Periods. Singapore: NUS Press. ISBN 9789971695057.

- Purton, Peter (2010), A History of the Late Medieval Siege 1200-1500, The Boydell Press, ISBN 9781843834496

- Vu, Hong Lien; Sharrock, Peter (2014). Descending Dragon, Rising Tiger: A History of Vietnam. Reaktion Books. ISBN 9781780233888.

- Grousset, René (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-1304-1.

- Aymonier, Etienne (1893). The Imperial and Asiatic Quarterly Review and Oriental and Colonial Record. Oriental University Institute. ISBN 978-1149974148.

- Walker, Hugh Dyson (2012). East Asia: A New History. ISBN 1477265163.

- Dutton, George; Werner, Jayne; Whitmore, John K., eds. (2012). Sources of Vietnamese Tradition. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-51110-0.

- Stone, Zofia. Genghis Khan: A Biography. Vij Books India Pvt Ltd. ISBN 978-93-86367-11-2.

- Hall, Kenneth R. (2008). Secondary Cities and Urban Networking in the Indian Ocean Realm, C. 1400-1800. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-2835-0.

- Haw, Stephen G. (2013). "The Deaths of Two Khaghans". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 76 (3): 361–371. doi:10.1017/S0041977X13000475.

- Taylor, Keith W. (2013). A History of the Vietnamese. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107244351.

- Simons, G. (1998). The Vietnam Syndrome: Impact on US Foreign Policy. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0333711279.

Primary sources

- Harris, Peter (2008), The Travels of Marco Polo, the Venetian, Alfred A. Knopf, ISBN 978-0307269133

- Lê, Tắc (1961), An Nam chí lược, A brief history of Annam, University of Hue

- Polo, Marco. (1920) The Travels of Marco Polo, Translated by Henry Yule. Edited and Annotated by Henri Cordier. John Murray: London.

- Rustichello da Pisa, The Travels of Marco Polo

- Song Lian (宋濂), History of Yuan (元史)

- Rashid-al-Din Hamadani, Jami' al-tawarikh, mentions Đại Việt as Kafjih-Guh or Giao Chỉ Quốc in Arabic. See Macro Polo's Caugigu.

See also

- Kingdom of Champa

- Battle of Bạch Đằng (1288)

- Tran Hung Dao

- Yuan dynasty

- Kublai Khan

- Mongol invasions

- Trần dynasty military tactics and organization

- Mongol military tactics and organization

| This image is available from the United States Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division under the digital ID {{{id}}} This tag does not indicate the copyright status of the attached work. A normal copyright tag is still required. See Wikipedia:Copyrights for more information. |

- Invasions by the Mongol Empire

- Wars involving Vietnam

- Wars involving the Yuan dynasty

- 1250s conflicts

- 1280s conflicts

- 1280s in Asia

- History of Champa

- 1257 in the Mongol Empire

- 1258 in the Mongol Empire

- 1284 in the Mongol Empire

- 1285 in the Mongol Empire

- 1287 in the Mongol Empire

- 1288 in the Mongol Empire

- Invasions of Vietnam

- Kublai Khan

- 13th century in Vietnam

- Wars between China and Vietnam