The Crying Game

| The Crying Game | |

|---|---|

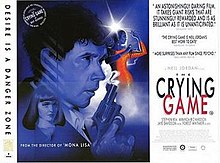

UK quad poster | |

| Directed by | Neil Jordan |

| Written by | Neil Jordan |

| Produced by | Stephen Woolley |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Ian Wilson |

| Edited by | Kant Pan |

| Music by | Anne Dudley |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by |

|

Release dates |

|

Running time | 111 minutes[1] |

| Countries |

|

| Language | English |

| Budget | £2.3 million |

| Box office | |

The Crying Game is a 1992 thriller film written and directed by Neil Jordan, produced by Stephen Woolley, and starring Stephen Rea, Miranda Richardson, Jaye Davidson, Adrian Dunbar, Ralph Brown and Forest Whitaker. The film explores themes of race, gender, nationality, and sexuality against the backdrop of the Troubles in Northern Ireland.

The film follows Fergus (Rea), a member of the IRA, who has a brief but meaningful encounter with a British soldier, Jody (Whitaker), who is being held prisoner by the group. Fergus later develops an unexpected romantic relationship with Jody's lover, Dil (Davidson), whom Fergus promised Jody he would take care of. Fergus is forced to decide between what he wants and what his nature dictates he must do.

A critical and commercial success, The Crying Game won the BAFTA Award for Best British Film as well as the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay, alongside Oscar nominations for Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actor for Rea, Best Supporting Actor for Davidson, and Best Film Editing. In 1999, the British Film Institute named it the 26th-greatest British film of all time.

Plot

At a fairground in rural Northern Ireland, a Provisional IRA volunteer named Fergus and a unit of other IRA members, led by a man named Maguire, kidnap a black British soldier named Jody after a female member of their unit, Jude, lures Jody to a secluded area by promising sex. They ransom Jody for the release of an imprisoned IRA member, threatening to kill him in three days if their demands are not met. While Fergus stands guard over Jody, the two bond, much to the chagrin of the other group members. Jody tells Fergus the fable of the Scorpion and the Frog.

Jody gets Fergus to promise to seek out Jody's girlfriend Dil in London should Jody be killed. The deadline set by Jody's captors passes with their demands unmet, and Fergus is ordered to take Jody into the woods to kill him. When Jody tries to escape, Fergus pursues him but cannot bring himself to shoot the fleeing man in the back. However, as it moves in to attack the IRA safehouse, a British armoured personnel carrier accidentally runs over and kills Jody. With his companions seemingly killed in the attack, Fergus flees to London, where he takes a job as a day labourer using the alias "Jimmy".

A few months later, Fergus finds Dil, working as a stylist at a hair salon. Later, they talk in a bar, where a drunken customer torments Dil, and Fergus follows the pair, who return to Dil's apartment for sex. Fergus, consumed by guilt over Jody's death, pursues Dil, protecting her from her obsessive suitor, and soon begins falling in love with her. Their relationship progresses, but when the two prepare to become intimate in Dil's apartment, Dil removes her clothes and reveals her transgender status. Fergus is initially revulsed; he rushes to the bathroom to vomit after hitting Dil in the face, and then leaves her apartment. A few days later, Fergus leaves Dil a note in her mailbox apologizing and the two reconcile; despite Fergus's initial shock at Dil being transgender, he is still taken by her. Around the same time, Jude unexpectedly reappears and tells Fergus that the IRA has tried and convicted him of treason in absentia. She forces him to agree to help assassinate a British judge, and mentions that she knows about Fergus and Dil, warning him that the IRA will kill Dil if he does not cooperate.

Fergus continues to woo Dil. To shield her from possible retribution, he cuts her hair short and dresses her in Jody's old cricket uniform as a disguise. The night before the IRA mission is to be carried out, Dil gets drunk and Fergus escorts her to her apartment, where she asks him to never leave her again. Fergus stays with her, and admits his role in Jody's death. Dil, drunk, appears not to understand; however, in the morning, before Fergus wakes up, Dil restrains him by tying his arms and legs to the bed with stockings, leaving Fergus unable to complete the assassination. Holding Fergus at gunpoint with his own pistol, Dil demands that he tell her that he loves her and will never leave her; he complies, and she unties him.

Jude and Maguire shoot the judge, but in turn, an armed bodyguard shoots and kills Maguire. The vengeful Jude enters Dil's flat with a gun, seeking to kill Fergus for not taking part in the assassination. Dil shoots Jude repeatedly, telling her she is aware that Jude was complicit in Jody's death and used her sexuality to trick him. Dil finally kills Jude with a shot to the neck. She then points the gun at Fergus, but lowers it, saying that she cannot kill him because Jody will not allow her to. Fergus prevents Dil from shooting herself and tells her to go into hiding. He wipes her fingerprints off the gun, replaces them with his own, and allows himself to be arrested in her place. A few months later, Dil goes to visit Fergus in prison and asks why he took the fall for her. He responds, "As a man once said, it's in my nature," and tells her the story of the Scorpion and the Frog that he heard from Jody.

Cast

- Stephen Rea as Fergus

- Miranda Richardson as Jude

- Forest Whitaker as Jody

- Jaye Davidson as Dil

- Adrian Dunbar as Peter Maguire

- Tony Slattery as Deveroux

- Jim Broadbent as Col

- Birdy Sweeney as Tommy

- Ralph Brown as Dave

- Andrée Bernard as Jane

- Joe Savino as Eddie

- Breffni McKenna as Tinker

- Jack Carr as Franknum

Production

Neil Jordan first drafted the screenplay in the mid-1980s under the title The Soldier's Wife, but shelved the project after a similar film was released. A 1931 short story by Frank O'Connor called Guests of the Nation, in which IRA soldiers develop a bond with their English captives, whom they are ultimately forced to kill,[4] partly inspired the story. The original draft had the character Dil as a cisgender woman, but Jordan decided to make the character transgender at the premiere of his film The Miracle at the 41st Berlin International Film Festival in 1991.[4]

Jordan sought to begin production of the film in the early 1990s, but found it difficult to secure financing,[4] as the script's controversial themes and his recent string of box office flops discouraged potential investors. Several funding offers from the United States fell through because the funders wanted Jordan to cast a woman to play the role of Dil, believing that it would be impossible to find an androgynous male actor who could pass as female.[5] Derek Jarman eventually referred Jordan to Jaye Davidson,[5] who, as a man, was completely new to acting, and was spotted by a casting agent while attending a premiere party for Jarman's film Edward II.[4] Rea later said, "'If Jaye hadn't been a completely convincing woman, my character would have looked stupid'".[6] The film included full-frontal male nudity; Davidson was filmed nude in the notable "surprise" scene in which Dil's gender identity was revealed.[7]

The film went into production with an inadequate patchwork of funding, leading to a stressful and unstable filming process. The producers constantly searched for small amounts of money to keep the production going, and the unreliable pay left crew members disgruntled. Costume designer Sandy Powell had an extremely small budget to work with and ended up having to lend Davidson some of her own clothes to wear in the film, as the two happened to be the same size.[4]

The film was known as The Soldier's Wife for much of its production, but Stanley Kubrick, a friend of Jordan, counselled against the title, which he said would lead audiences to expect a war film. The opening sequence was shot in Laytown, County Meath, Ireland, and the rest in London and Burnham Beeches, Buckinghamshire, England.[8] The bulk of the film's London scenes were shot in the East End, specifically Hoxton and Spitalfields.[9] Dil's flat is in a building facing onto Hoxton Square, with the exterior of the Metro on nearby Coronet Street. Fergus's flat and Dil's hair salon are both in Spitalfields. Chesham Street in Belgravia was the location for the assassination of the judge, with the now-defunct Lowndes Arms pub just around the corner.[9]

Release

The film was shown at festivals in Italy, the US and Canada in September, and originally released in Ireland and the UK in October 1992, where it failed at the box office. Director Neil Jordan, in later interviews, attributed this failure to the film's heavily political undertone, particularly its sympathetic portrayal of an IRA fighter. The bombing of a pub in London is specifically mentioned as turning the English press against the film.[10]

The then-fledgling film company Miramax Films decided to promote the film in the United States where it became a sleeper hit, earning over $60 million at the box office. A memorable advertising campaign generated intense public curiosity by asking audiences not to reveal the film's "secret" regarding Dil's gender identity.[6] Those surveyed by CinemaScore on opening night gave the film a grade "B" on a scale of A+ to F.[11] Jordan also believed the film's success was a result of the film's British–Irish politics being either lesser-known or completely unknown to American audiences, who flocked to the film for what Jordan called "the sexual politics".

The film earned critical acclaim and was nominated for six Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Best Film Editing, Best Actor (Rea), Best Supporting Actor (Davidson) and Best Director. Writer-director Jordan finally won the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay. The film went on to success around the world, including re-releases in Britain and Ireland.

Critical reception

The Crying Game received worldwide acclaim from critics. The film has a 94% "fresh" rating on Rotten Tomatoes based on 67 reviews, with an average rating of 8.20/10. The consensus states, "The Crying Game is famous for its shocking twist, but this thoughtful, haunting mystery grips the viewer from start to finish."[12]

Roger Ebert awarded the film a rating of four out of four stars, describing it in his review as one that "involves us deeply in the story, and then it reveals that the story is really about something else altogether" and named it "one of the best films of 1992."[13]

Richard Corliss, in Time magazine, stated: "And the secret? Only the meanest critic would give that away, at least initially." He revealed the film's secret by means of an acrostic, forming a sentence from the first letter of each paragraph.[14]

Much has been written about The Crying Game's discussion of race, nationality and sexuality. Theorist and author Judith Halberstam argued that Dil's transvestism and the viewer's placement in Fergus's point of view reinforces societal norms rather than challenging them.[15]

The Crying Game was placed on over 50 critics' ten-best lists in 1992, based on a poll of 106 film critics.[16]

Awards and nominations

| Category | Nominee(s) | Result |

|---|---|---|

| Best Picture | Stephen Woolley | Nominated |

| Best Director | Neil Jordan | Nominated |

| Best Actor | Stephen Rea | Nominated |

| Best Supporting Actor | Jaye Davidson | Nominated |

| Best Screenplay – Written Directly for the Screen | Neil Jordan | Won |

| Best Film Editing | Kant Pan | Nominated |

| Category | Nominee(s) | Result |

|---|---|---|

| Best Film | Stephen Woolley and Neil Jordan | Nominated |

| Best British Film | Won | |

| Best Direction | Neil Jordan | Nominated |

| Best Actor in a Leading Role | Stephen Rea | Nominated |

| Best Actor in a Supporting Role | Jaye Davidson | Nominated |

| Best Actress in a Supporting Role | Miranda Richardson | Nominated |

| Best Original Screenplay | Neil Jordan | Nominated |

| Category | Nominee(s) | Result |

|---|---|---|

| Best Motion Picture – Drama | The Crying Game | Nominated |

Critics awards

| Award | Category | Nominee(s) | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Argentine Film Critics Association Awards | Best Foreign Film | Neil Jordan | Nominated |

| Awards Circuit Community Awards | Best Director | Nominated | |

| Best Actor in a Supporting Role | Jaye Davidson | Nominated | |

| Best Actress in a Supporting Role | Miranda Richardson | Nominated | |

| Best Original Screenplay | Neil Jordan | Nominated | |

| Best Film Editing | Kant Pan | Nominated | |

| Boston Society of Film Critics Awards | Best Screenplay | Neil Jordan | Won |

| Chicago Film Critics Association Awards | Best Film | Stephen Woolley | Nominated |

| Best Foreign Language Film | The Crying Game | Won | |

| Best Director | Neil Jordan | Nominated | |

| Best Supporting Actress | Miranda Richardson | Nominated | |

| Best Screenplay | Neil Jordan | Nominated | |

| Most Promising Actor | Jaye Davidson | Nominated | |

| Most Promising Actress | Nominated | ||

| Dallas-Fort Worth Film Critics Association Awards | Best Film | The Crying Game | Nominated |

| London Film Critics' Circle Awards | British Director of the Year | Neil Jordan | Won |

| British Screenwriter of the Year | Won | ||

| British Producer of the Year | Stephen Woolley | Won | |

| Los Angeles Film Critics Association Awards | Best Foreign Language Film | Neil Jordan | Won |

| Best Supporting Actress | Miranda Richardson | Nominated | |

| Best Screenplay | Neil Jordan | Nominated | |

| National Board of Review Awards | Top Ten Films | The Crying Game | Won |

| Most Auspicious Debut | Jaye Davidson | Won | |

| National Society of Film Critics Awards | Best Film | The Crying Game | Nominated |

| Best Director | Neil Jordan | Nominated | |

| Best Actor | Stephen Rea | Won | |

| Best Supporting Actor | Jaye Davidson | Nominated | |

| Best Supporting Actress | Miranda Richardson | Nominated | |

| Best Screenplay | Neil Jordan | Nominated | |

| New York Film Critics Circle Awards | Best Supporting Actress | Miranda Richardson (also for Enchanted April and Damage) | Won |

| Best Screenplay | Neil Jordan | Won | |

| Southeastern Film Critics Association Awards | Best Picture | The Crying Game | Nominated |

Guild awards

| Award | Category | Nominee(s) | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Directors Guild of America Awards | Outstanding Directorial Achievement in Motion Pictures | Neil Jordan | Nominated |

| Producers Guild of America Awards | Outstanding Producer of Theatrical Motion Pictures | Stephen Woolley | Won |

| Writers Guild of America Awards | Best Screenplay Written Directly for the Screenplay | Neil Jordan | Won |

| Writers' Guild of Great Britain Awards | Film – Screenplay | Won |

Other awards

Soundtrack

The soundtrack to the film, The Crying Game: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack, released on 23 February 1993, was produced by Anne Dudley and Pet Shop Boys. Boy George scored his first hit since 1987 with his recording of the title song – a song that had been a hit in the 1960s for British singer Dave Berry. The closing rendition of Tammy Wynette's "Stand by Your Man" was performed by American singer Lyle Lovett.

- "The Crying Game" – Boy George

- "When a Man Loves a Woman" – Percy Sledge

- "Live for Today" (Orchestral) – Cicero and Sylvia Mason-James

- "Let the Music Play" – Carroll Thompson

- "White Cliffs of Dover" – The Blue Jays

- "Live for Today" (Gospel) – David Cicero

- "The Crying Game" – Dave Berry

- "Stand by Your Man" – Lyle Lovett

- "The Soldier's Wife"*

- "It's in my Nature"*

- "March to the Execution"*

- "I'm Thinking of You"*

- "Dies Irae"*

- "The Transformation"*

- "The Assassination"*

- "The Soldier's Tale"*

*Orchestral tracks composed by Anne Dudley and performed by the Pro Arte Orchestra of London

See also

- Breakfast on Pluto (2005)

- List of films featuring the Irish Republican Army

- List of transgender characters in film and television

- List of transgender-related topics

- BFI Top 100 British films

References

- ^ "The Crying Game (18)". British Board of Film Classification. 28 August 1992. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- ^ "The Crying Game". BFI. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ a b Rufus Olins (24 September 1995). "Mr Fixit of the British Screen". The Sunday Times. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- ^ a b c d e British Film Institute (21 February 2017). In conversation with The Crying Game cast. YouTube. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ^ a b Jack Watkins (21 February 2017). "How we made The Crying Game". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ^ a b Giles, Jeff (1 April 1993). "Jaye Davidson: Oscar's Big Surprise". Retrieved 21 June 2019.

- ^ Vineyard, Jennifer (5 December 2014). "Stephen Rea on The Crying Game's Surprise Penis". Vulture.com. Retrieved 21 June 2019.

- ^ Presenter: Francine Stock (17 September 2010). "The Film Programme". The Film Programme. London. BBC. BBC Radio 4.

- ^ a b Oliver Lunn (26 January 2018). "How London has changed since the Crying Game". British Film Institute. Retrieved 26 May 2018.

- ^ "The Crying Game". Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ "CRYING GAME, THE (1993) B". CinemaScore. Archived from the original on 20 December 2018.

- ^ The Crying Game at Rotten Tomatoes

- ^ Ebert, Roger (18 December 1992). "The Crying Game". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on 3 June 2013. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ Corliss, Richard. "Queuing For The Crying Game", Time, 25 January 1993.

- ^ Halberstam, Judith (2005), In a Queer Time and Place: Transgender Bodies, Subcultural Lives, New York: New York University Press, p. 81. ISBN 978-0-8147-3585-5.

- ^ "106 Doesn't Add Up". LA Times. 24 January 1993. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

External links

- 1992 films

- 1990s crime drama films

- 1990s crime thriller films

- 1992 independent films

- 1992 LGBT-related films

- 1990s thriller drama films

- BAFTA winners (films)

- Bisexuality-related films

- British films

- British crime thriller films

- British independent films

- British LGBT-related films

- Irish LGBT-related films

- English-language films

- Films about interracial romance

- Films about the Irish Republican Army

- Films about The Troubles (Northern Ireland)

- Films set in London

- Films set in Northern Ireland

- Films shot in Buckinghamshire

- Films shot in Ireland

- Films shot in London

- LGBT-related political films

- LGBT-related romantic drama films

- LGBT-related thriller films

- Political thriller films

- Films about trans women

- Films directed by Neil Jordan

- Films produced by Elizabeth Karlsen

- Palace Pictures films

- Films whose writer won the Best Original Screenplay Academy Award

- Anthony Award-winning works

- Best British Film BAFTA Award winners

- Independent Spirit Award for Best Foreign Film winners

- Films scored by Anne Dudley

- 1992 drama films