Nord Stream pipelines sabotage

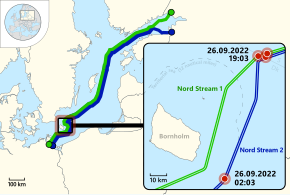

Map showing the location of the Nord Stream 1 and Nord Stream 2 pipeline explosions near Bornholm. The two run close to each other most of the way, but deviate near the sites of the sabotage.[1] | |

| Date | 26 September 2022 |

|---|---|

| Location | Central Baltic Sea, near Bornholm, Denmark |

| Coordinates | |

| Type | |

| Cause | Sabotage[4][5][6][7] |

| Motive | Unknown |

| Target | Nord Stream 1 and Nord Stream 2 |

| Perpetrator | Unknown |

| First reporter | Nord Stream AG |

| Property damage |

|

On 26 September 2022, a series of clandestine bombings and subsequent underwater gas leaks occurred on the Nord Stream 1 and Nord Stream 2 natural gas pipelines. Both pipelines were built to transport natural gas from Russia to Germany through the Baltic Sea, and are majority owned by the Russian majority state-owned gas company, Gazprom. The perpetrators' identities and the motives behind the sabotage remain debated.

Prior to the leaks, the pipelines had not been operating due to disputes between Russia and the European Union in the wake of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, but were filled with natural gas. On 26 September at 02:03 local time (CEST), an explosion was detected originating from Nord Stream 2; a pressure drop in the pipeline was reported and natural gas began escaping to the surface southeast of the Danish island of Bornholm. Seventeen hours later, the same occurred to Nord Stream 1, resulting in three separate leaks northeast of Bornholm.[8][9] All three affected pipes were rendered inoperable; Russia has confirmed one of the two Nord Stream 2 pipes is operable and is thus ready to deliver gas through Nord Stream 2.[10] The leaks occurred one day before Poland and Norway opened the Baltic Pipe running through Denmark, bringing in gas from the North Sea, rather than from Russia as the Nord Stream pipelines do.[11][12] The leaks are located in international waters (not part of any nation's territorial sea), but within the economic zones of Denmark and Sweden.[13]

Nord Stream AG, the Gazprom-owned operator of Nord Stream, said the pipelines had sustained "unprecedented" damage in one day.[14] On 29 September, Russian President Vladimir Putin called the attack on the pipeline "an unprecedented act of international terrorism".[15][16]

Background

In 2021, Russia supplied roughly 45% of the natural gas imported by European Union states.[17] The United States has been a major opponent of the Nord Stream pipelines. Former US President Donald Trump said in 2019 that Nord Stream 2 could turn Europe into a "hostage of Russia" and placed sanctions on any company assisting Russia to complete the pipeline.[18] In December 2020, then President-elect Joe Biden came out forcefully against the opening of the new pipeline and the impact this would have on potential Russian influence. In 2021, the Biden administration lifted the sanctions, stating that while it was "unwavering" in opposition to Nord Stream 2, removing the sanctions was a matter of national interest, to maintain positive relations with Germany and other US allies in Europe.[19] The second pipeline was completed in September 2021.[20]

Timeline

The Geological Survey of Denmark said that a seismometer on Bornholm showed two spikes on 26 September: the first P wave at 02:03 local time (CEST) indicated a magnitude of 2.3 and the second at 19:03 a magnitude of 2.1.[21] Similar data were provided by a seismometer at Stevns, and by several seismometers in Germany, Sweden (as far away as the station in Kalix 1,300 kilometres or 810 miles north), Finland and Norway.[22] The seismic data were characteristic of underwater explosions, not natural events, and showed that they happened near the locations where the leaks were later discovered.[23][21][24] Around the same time, pressure in the non-operating pipeline dropped from 10.50 to 0.70 megapascals (105 to 7 bar), as recorded by Nord Stream in Germany.[25][23][26]

After Germany's initial report of pressure loss in Nord Stream 2, a gas leak from the pipeline was discovered by a Danish F-16 interceptor response unit to the southeast of Dueodde, Bornholm.[27][28] Nord Stream 2 consists of two parallel lines and the leak happened in line A inside the Danish economic zone.[29] Citing danger to shipping, Danish Maritime Authority closed the sea for all vessels in a 5 nautical miles (9.3 km; 5.8 mi) zone around the leak site, and advised planes to stay at least 1,000 m (3,300 ft) above it.[28][30] The pipe, which was not operating, had 300 million cubic metres (11 billion cubic feet) of pressurized gas in preparation for its first deliveries.[31]

An environmental impact assessment of NS2 was made in 2019. By 2012, corrosion leaks had only occurred in two large pipelines worldwide. Leaks due to military-type acts and mishaps were considered "very unlikely". The largest leak in the analysis was defined as a "full-bore rupture (>80 mm [3.1 in])", for example from a sinking ship hitting the pipeline. Such an unlikely large leak from 54 metres (177 ft) water depth could result in a gas plume up to 15 metres (49 ft) wide at the surface.[32]

For NS2, the pipes have an outer diameter of approximately 1,200 millimetres (48 inches) and a steel wall thickness of 27–41 millimetres (1.1–1.6 in) – thickest at the pipe ingress where operating pressure is 22 megapascals (220 bar) and thinnest at the pipe egress where operating pressure is 17.7 megapascals (177 bar), when transporting gas. To weigh down the pipe (to ensure negative buoyancy), a 60–110-millimetre (2.4–4.3 in) layer of concrete surrounds the steel.[33] Each line of the pipeline was made of about 100,000 concrete-weight coated steel pipes each weighing 24 tonnes (53,000 lb) welded together and laid on the seabed. To facilitate pigging, the pipelines have a constant internal diameter of 1,153 millimetres (45.4 in), according to Nord Stream. Sections lie at a depth of around 80–110 metres (260–360 ft).[25]

Hours after the German office of Nord Stream AG had reported pressure loss in Nord Stream 1, two gas leaks were discovered on that pipeline by Swedish authorities.[24][34] Both parallel lines of Nord Stream 1 are ruptured and the sites of its two leaks are about 6 km (3.7 mi) from each other, with one in the Swedish economic zone and the other in the Danish economic zone.[9][29] On 28 September, the Swedish Coast Guard clarified that the initially reported leak in the Swedish economic zone actually was two leaks located near each other, bringing the total number of leaks on the Nord Stream pipes to four (two in the Swedish economic zone, two in the Danish).[9][35]

While none of the pipelines were delivering supplies to Europe, both Nord Stream 1 and 2 were pressurized with gas.[36]

Danish Defence posted a video of the gas leak on their website which showed that, as of 27 September, the largest of the leaks created turbulence on the water surface of approximately 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) in diameter. The smallest leak made a circle of about 200 metres (660 ft) in diameter.[27] Analysts noted the much larger plumes as an indication that the rupture is very large,[22] compared to a presumed technical leak plume of 15 metres (49 ft).[32]

The SwePol power cable between Sweden and Poland passes near two of the leak sites, and was investigated for damage.[37] Tests by Svenska Kraftnät, published on 4 October, indicated the cable was not damaged.[38]

Swedish Navy ships were scouting for two days in nearby proximity where Nord Stream 1 and 2 were later subjected to sabotage. The search was carried out between Thursday and Saturday, but from the night of Sunday to Monday, no Swedish ships were at the site.[39][40]

On 1 October, the Danish Energy Agency reported that one of the two pipelines, Nord Stream 2, appeared to have stopped leaking gas as the pressure inside the pipe had stabilized.[41] The following day, the same agency reported that the pressure had stabilized in both Nord Stream 1 pipelines as well, indicating that the leakage had stopped.[42] In contrast, Swedish authorities reported on 2 October that gas continues to escape from the two leaks in their economic zone, albeit to a lesser extent than a few days ago.[43]

The leaks

| Pipe | Location | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Nord Stream 2 pipe A | exclusive economic zone of Denmark | discovered by a Danish F-16 interceptor response unit to the southeast of Dueodde, Bornholm |

| Nord Stream 2 pipe A | exclusive economic zone of Sweden | discovered on that pipeline by Swedish authorities |

| Nord Stream 1 pipe A | exclusive economic zone of Sweden | discovered on that pipeline by Swedish authorities |

| Nord Stream 1 pipe B | exclusive economic zone of Denmark | discovered on that pipeline by Swedish authorities |

Possibility of repairs

On 27 September 2022, Nord Stream AG, the operator of Nord Stream, said it was impossible to estimate when the infrastructure would be repaired.[44] German authorities stated that unless they were rapidly repaired, the three damaged lines, both lines in Nord Stream 1 and line A in Nord Stream 2, were unlikely to ever become operational again due to corrosion caused by sea water.[1] The Washington Post reported that the incidents are likely to put a permanent end to both Nord Stream projects.[45]

According to engineers, possible methods for the repair of the pipeline would include full-scale replacement of pipe segments and clamping of damaged sections. If carried out, repairs would be expected to last several months.[46]

In February 2023, The Times reported that Russia had begun estimating repair costs, put at about $500 million.[47]

Cause

Sweden's Prime Minister Magdalena Andersson said that it likely was sabotage and also mentioned the detonations.[48] The Geological Survey of Denmark said that the tremors that had been detected were unlike those recorded during earthquakes, but similar to those recorded during explosions.[49] The Swedish public service broadcaster SVT reported that measuring stations in both Sweden and Denmark recorded strong underwater explosions near the Nord Stream pipelines. Björn Lund, Associate Professor in Seismology at The Swedish National Seismic Network said "there is no doubt that these were explosions" at an estimated 100-kilogram (220 lb) TNT equivalent.[24] European Union officials blamed sabotage, as did the secretary general of NATO, Jens Stoltenberg, and the Prime Minister of Poland, Mateusz Morawiecki.[50][51][52]

The Kremlin said that it did not rule out sabotage as a reason for the damage to the Nord Stream pipelines.[53] Dmitry Peskov, the Kremlin spokesman, said: "We cannot rule out any possibility right now. Obviously, there is some sort of destruction of the pipe. Before the results of the investigation, it is impossible to rule out any option."[54][55]

The German newspaper Der Tagesspiegel wrote that the leaks are being investigated for whether they may have been caused by targeted attacks by submarine or clearance divers.[56]

According to German Federal Government circles, photos taken by the Federal Police with the support of the navy show a leak 8 metres (26 ft) long, which could only be the result of explosives.[57]

On 11 November 2022, Wired reported that satellite imagery revealed two large unidentified ships which had turned off their AIS trackers and had appeared around the site of the leaks in the days before the gas leaks were detected.[58]

On 18 November 2022, Swedish authorities announced that remains of explosives were found at the site of the leaks, and confirmed that the incident was the result of sabotage.[6][7]

Investigations

The day after the leaks occurred, the Swedish Police Authority opened an investigation of the incident, calling it "major sabotage". The investigation is conducted in cooperation with other relevant authorities as well as the Swedish Security Service.[59] A similar investigation was opened in Denmark. The two nations were in close contact, and had also been in contact with other countries in the Baltic region and NATO.[48][60] Because it happened within international waters (not part of any nation's territorial sea, although within the Danish and Swedish economic zones), neither the Danish Prime Minister nor the Swedish Prime Minister regarded it as an attack on their nation.[61][48] On 2 October, Nancy Faeser, German Minister of the Interior and Community, announced that Germany, Denmark and Sweden intend to form a joint investigation team to investigate these seeming acts of sabotage.[5]

Russia reportedly dispatched naval vessels to join Swedish and Danish maritime experts at the leak sites. Foreign Policy reported that since the pipelines are Russian-state owned and since the sabotage is not considered a military attack, investigations may be complicated by Russian involvement.[62] Moscow demanded to be part of the investigations conducted by Denmark and Sweden, but both countries refused, telling Russia to conduct its own investigations.[63]

On 6 October, the Swedish Security Service said its preliminary investigations in the Swedish exclusive economic zone showed extensive damage and they "found evidence of detonations",[64] strengthening "the suspicions of serious sabotage".[65]

On 10 October, the German Public Prosecutor General launched an investigation into suspected intentional causing of an explosion and anti-constitutional sabotage. The procedure is directed against unknown persons. According to the federal authority, it is responsible because it was a serious violent attack on national energy supply, likely to impair Germany's external and internal security. The Federal Criminal Police Office and the Federal Police were commissioned to investigate.[66] The Federal Police had already started an investigative mission with assistance from the German Navy. Investigators took photos with a Navy underwater drone that showed a leak 8 metres (26 ft) long. This could only have been caused by explosives, it was said in government circles.[57]

On 14 October, Russia's foreign ministry summoned German, Danish and Swedish envoys to express "bewilderment" over the exclusion of Russian experts from investigations and protesting reported participation of the United States, saying that Russia would not recognise any "pseudo-results" without the involvement of its own experts.[67]

Also on 14 October, the Swedish prosecutor announced that Sweden would not set up a joint investigation team with Denmark and Germany because that would transfer information related to Swedish national security. German public broadcaster ARD also reported that Denmark had rejected a joint investigation team.[68] On 18 November, the Swedish Security Service concluded that the incident was an act of "gross sabotage", stating that traces of explosives were found on the pipes.[69] Also on 18 October, the Swedish newspaper Expressen released photos it had commissioned of the Nord Stream 1 damage, showing at least 50 m (160 ft) of pipe missing from its trench, as well as steel debris around the site.[70][71]

On 15 October the left-wing German party Die Linke made a parliamentary inquiry to the government. The German government claimed that no on-site investigation had taken place yet, and refused to disclose information about the presence of NATO or Russian ships near Bornholm on the day of the presumed sabotage, citing state secret.[72]

In February 2023, The Times stated that none of the three separate investigations had publicly assigned responsibility for the damage.[47]

On 17 February 2023, Russia formally submitted a proposal to the Security Council of the United Nations calling for an investigation into the Nord Stream sabotage, and reiterated its request on 20 February 2023.[73]

Speculation

Swedish and Danish Prime Ministers were both unwilling to speculate on who was responsible for the incidents.[74] Russia first accused the United Kingdom,[75] and later the United States, of being responsible for the sabotage.[47]

Involvement by Russia

CNN reported that European security officials observed Russian Navy support ships nearby where the leaks later occurred on 26 and 27 September. One week prior, Russian submarines were also observed nearby.[76]

In September 2022, the former head of Germany's Federal Intelligence Service (BND), Gerhard Schindler, alleged that Russia sabotaged the gas pipelines to justify their halting of gas supplies prior to the explosion and said Russia's "halt in gas supplies can now be justified simply by pointing to the defective pipelines, without having to advance alleged turbine problems or other unconvincing arguments for breaking supply contracts.”[77]

Finland's national public broadcasting company Yle compared the incident to the two explosions on a gas pipeline in North Ossetia in January 2006, which were caused by remote-controlled military-grade charges.[78] The explosions halted Russian gas supply to Georgia after the country had started seeking NATO membership.[78]

In December 2022, The Washington Post reported that after months of investigation, there was no conclusive evidence that Russia was behind the attack, and many European and US officials no longer suspected that Russia was involved.[79]

Involvement by the United States

Der Spiegel reported that the United States Central Intelligence Agency had warned the German government of possible sabotage to the pipelines weeks beforehand.[80] The New York Times reported that the CIA had warned various European governments sometime in June.[81]

In a widely shared post on Twitter, Polish MEP and former foreign affairs and defence minister Radek Sikorski stated simply, "Thank you, USA", next to a photo of bubbling water above the pipeline damage. He followed up to clarify that this was only speculation on his part,[82] and that his view was based in part on a February joint press conference of US President Joe Biden and German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, during which Biden stated, "If Russia invades ... again, there will no longer be a Nord Stream 2. We will bring an end to it."[83][47] Sikorski's post was criticized by many politicians and government officials. Polish government spokesman Piotr Müller said it was harmful and served Russian propaganda.[82] US State Department spokesman Ned Price characterized the idea of US involvement in the pipeline damage as "preposterous".[84] Der Spiegel commented that Nord Stream 2 was already stopped entirely without explosives two days before Russia invaded Ukraine, and that what happened is exactly what Biden and Scholz had said would happen.[85] Sikorski deleted the original and all follow-up tweets several days later.[84]

At a United Nations Security Council meeting convened for the incident, Russian Federation representative Vasily Nebenzya suggested that the United States was involved in the pipeline damage.[86] Deutsche Welle fact check concluded that the Russian claim "that an American helicopter was responsible for the gas leaks is untenable and misleading." The helicopter never flew along the pipeline and the gas leak areas were at least 9 and 30 km away, respectively, from its flight path.[87][88]

On 2 February 2023, Russian foreign minister Sergei Lavrov said on Russian state television the U.S. had direct involvement in the explosions intended to help preserve U.S. global dominance.[47]

On 8 February 2023, American investigative journalist Seymour Hersh published an article on his Substack page in which he alleged that the attack was ordered by the White House and carried out utilizing American and Norwegian assets.[89][90][91][92] The post relied on a single anonymous source, whom Hersh described as having "direct knowledge of the operational planning."[93] The White House responded to the story by calling it "utterly false and complete fiction".[94] Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs said that those allegations are "nonsense".[95] Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov told Russian state-owned media RIA Novosti that "Our assumption was that the US and several NATO allies were involved in this disgusting crime." He also threatened unspecified “consequences” for the US.[96] Norwegian commentator Harald S. Klungtveit has challenged the accuracy of Hersh's claims, such as that Alta-class mine sweepers had participated in BALTOPS 22, or that Jens Stoltenberg has been cooperating with U.S. intelligence services since the Vietnam War (Stoltenberg was a teenager at the time).[97]

Involvement by other countries

On 29 October 2022, Russia accused a unit of the United Kingdom's Royal Navy of sabotaging the gas pipeline. This claim was denied by the UK Ministry of Defence which released a statement saying: "To detract from their disastrous handling of the illegal invasion of Ukraine, the Russian Ministry of Defence is resorting to peddling false claims of an epic scale".[75]

In late 2022, another former head of the BND, August Hanning, said that Russia, Ukraine, Poland and Britain had a plausible interest in disabling the pipelines, as well as the U.S. [47]

Aftermath

On 27 September 2022, European gas prices jumped 12 percent after news spread of the damaged pipelines,[98][99] despite the fact that Nord Stream 1 had not delivered gas since August and Nord Stream 2 had never gone into service.[100]

The Danish Navy and Swedish Coast Guard sent ships to monitor the discharge and keep other vessels away from danger by establishing an exclusion zone of 5 nautical miles (9.3 km; 5.8 mi) around each leak.[44][101] Two of the ships are the Swedish Amfitrite [sv] and the Danish Absalon, which are specially designed to operate in contaminated environments such as gas clouds.[101][102] Vessels could lose buoyancy if they enter the gas plumes, and there might be a risk of leaked gas igniting over the water and in the air, but there were no risks associated with the leaks outside the exclusion zones.

The president of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, wrote on Twitter that "Any deliberate disruption of active European energy infrastructure is unacceptable & will lead to the strongest possible response."[103] After the leaks, Norwegian authorities increased the security around their gas and oil infrastructure.[104] As of 29 September 2022[update], eastward flow of gas from Germany to Poland through the Yamal–Europe pipeline was stable,[105][106] as was transmission through Ukraine as of 2 October 2022[update],[107] although concerns remained that Russia may introduce "sanctions against Ukraine's Naftogaz [...] that could prohibit Gazprom from paying Ukraine transit fees [... that] could end Russian gas flows to Europe via the country."[105][106][108][109]

On 5 October, Nord Stream 2 AG reported that Gazprom had begun pulling gas back out of the undamaged pipe for consumption in Saint Petersburg, reducing pipe pressure.[110] Infrastructure in the North Sea was being inspected for anomalies.[111]

On 11 January 2023, EU and NATO announced the creation of a task force on making their critical infrastructure more resilient to potential threats, citing "Putin’s weaponising of energy" and the sabotage of the Nord Stream pipelines.[112]

Environmental impact

In the area, the leaks would only affect the environment where the gas plumes in the water column are located. A greater effect is likely to be the climate impact caused by the large volumes of escaping methane, a potent greenhouse gas.[25][113] The released volume is approximately 0.25% of the annual capacity of the pipelines, an amount nearly equal to the total release from all other sources of methane in a full year across Sweden.[114] A Danish official said these Nord Stream gas leaks could emit a CO2 equivalent of 14.6 million tonnes (32 billion pounds), similar to one third of Denmark's total annual greenhouse gas emissions.[115][116]

The methane emissions from the leaks are equal to a few days of the emissions from regular fossil fuel production.[117] However, the leaks set a record as the single largest discharge of methane, dwarfing all previously known leaks, such as the Aliso Canyon gas leak.[117][118]

Equipment measured no increase in atmospheric methane at Bornholm.[119] A weather station in Norway logged an unprecedented 400 parts per billion (ppb) increase from a base level of 1800 ppb.[120]

Scientists from several European countries have analyzed the impact on marine ecosystems. The shockwave is stated to have killed marine life within a radius of 4 kilometer and have damaged the hearing of animals up to 50 kilometers. An estimated 250,000 mectric tons of seafloor sediment containing lead and tributyltin used in anti-fouling paint have been lifted up.[121] Additionally, the area is contaminated from the dumping of ammunitions and chemical waepons.[122]

See also

References

- ^ a b "Große Schäden an Gasleitungen: Nord-Stream-Röhren wohl für immer zerstört – Bundespolizei verstärkt Meeresschutz" (in German). Der Tagesspiegel. 28 September 2022. Archived from the original on 28 September 2022. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- ^ "Denmark. The Baltic Sea. Bornholm SE. Gas leakage. Danger to navigation. Prohibited area established" (PDF). Søfartsstyrelsen. 26 September 2022. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 October 2022. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

A gas leakage has been observed in pos. 54° 52.60'N – 015° 24.60'E.

- ^ a b c "Denmark. The Baltic Sea. Bornholm NE. Gas leakages. Danger to navigation. Prohibited areas established" (PDF). Søfartsstyrelsen. 29 September 2022. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 September 2022. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

Gas leakages have been observed in pos. 55° 33,40'N – 015° 47,30'E, pos. 55° 32,10'N – 015° 41,90'E and pos. 55° 32,450'N 015° 46,470'E.

- ^ Aitken, Peter (2 October 2022). "NATO chief: 'All evidence' points to pipeline sabotage, dodges question on Ukraine membership". Fox News. Archived from the original on 3 October 2022. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- ^ a b "Nancy Faeser kündigt internationale Ermittlungsgruppe an". Zeit Online (in German). Zeitverlag. 2 October 2022. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- ^ a b "Bekräftat sabotage vid Nord Stream". Åklagarmyndigheten (in Swedish). Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- ^ a b "Russia-Ukraine war live: remains of explosives found at Nord Stream pipeline blast site; 10m Ukrainians without power, says Zelenskiy". the Guardian. 18 November 2022. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- ^ "Now, Nord Stream 1 gas pipeline hit by two leaks in Baltic Sea". WION. Archived from the original on 1 October 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ a b c "Kustbevakningen: Fyra läckor på Nord Stream". Svenska Dagbladet. 28 September 2022. Archived from the original on 3 October 2022. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- ^ Hemicker, Lorenz; Käppel, Janina (5 October 2022). "Russland bestätigt Einsatzbereitschaft von Nord Stream 2" [Russia confirms Nord Stream 2 is operable]. Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (in German). Archived from the original on 6 October 2022.

Ende September kam es zu Explosionen unter Wasser an der Ostseepipeline. Dabei wurden beide Stränge der Pipeline Nord Stream 1 und ein Strang von Nord Stream 2 leck geschlagen.

- ^ Scislowska, Monika; Olsen, Jan M.; Keyton, David (28 September 2022). "Blasts precede Baltic pipeline leaks, sabotage seen likely". ABC News. American Broadcasting Company. Archived from the original on 1 October 2022. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- ^ "Gas Infrastructure Europe – System Development Map 2022/2021" (PDF). European Network of Transmission System Operators for Gas (ENTSOG). December 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 September 2022. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ^ "Nord Stream-selskab: Skader er uden fortilfælde" (in Danish). Berlingske. 27 September 2022. Archived from the original on 1 October 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ "Poland, Denmark fear 'sabotage' over Russian gas pipeline leaks". Al Jazeera English. Archived from the original on 30 September 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ "Путин заявил Эрдогану о "беспрецедентной диверсии" на "Северных потоках"". РБК (in Russian). Archived from the original on 30 September 2022. Retrieved 29 September 2022.

- ^ "Путин и Эрдоган обсудили по телефону ситуацию на Украине". Interfax.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 29 September 2022.

- ^ International Energy Agency (3 March 2022). "How Europe can cut natural gas imports from Russia significantly within a year". IEA. Retrieved 10 February 2023.

- ^ "Nord Stream 2: Trump approves sanctions on Russia gas pipeline". BBC News. 21 December 2019.

- ^ Markind, Daniel (21 May 2021). "Nord Steam 2 Saga Ends as Biden Waives Sanctions". Forbes. Retrieved 10 February 2023.

- ^ Soldatkin, Vladimir (10 September 2021). "Russia completes Nord Stream 2 construction, gas flows yet to start". Reuters. Retrieved 10 February 2023.

- ^ a b "GEUS har registreret rystelser i Østersøen" (in Danish). Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland. 27 September 2022. Archived from the original on 27 September 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ a b Viseth, Ellen Synnøve (27 September 2022). "Havet bobler: Universitetslektor frykter "meget stor eksplosjon"". Tu.no (in Norwegian). Teknisk Ukeblad. Archived from the original on 27 September 2022.

- ^ a b "Scandinavian seismic stations register explosions near pipelines, raising fears of sabotage". PBS. 27 September 2022. Archived from the original on 27 September 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ a b c Persson, Ida (27 September 2022). "Seismolog: Två explosioner intill Nord Stream". Sveriges Radio (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 30 September 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ a b c Chestney, Nina (27 September 2022). "Q+A What is known so far about the Nord Stream gas pipeline leaks". Reuters. Archived from the original on 27 September 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ Sanderson, Katharine (30 September 2022). "What do Nord Stream methane leaks mean for climate change?". Nature. doi:10.1038/d41586-022-03111-x. PMID 36180742. S2CID 252645440. Archived from the original on 1 October 2022. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- ^ a b "Gaslækage i Østersøen". Danish Defence (in Danish). Archived from the original on 27 September 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ a b "Læk på Nord Stream 2 rørledning i Østersøen". Danish Energy Agency (in Danish). 26 September 2022. Archived from the original on 30 September 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ a b "Læk på gasledninger: Det ved vi, og det mangler vi svar på" (in Danish). TV 2. 28 September 2022. Archived from the original on 27 September 2022. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- ^ "Nord Stream pipelines hit by gas leaks". Sveriges Radio. 27 September 2022. Archived from the original on 27 September 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ Gosden, Emily (27 September 2022). "Nord Stream 2: Gas leaks into Baltic Sea after reports of explosions". The Times. Archived from the original on 27 September 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ a b "Offentlig høring af miljøkonsekvensrapport – Nord Stream 2 sydøst om Bornholm (Environmental impact assessment)". Energistyrelsen (in Danish). 3 May 2019. Archived from the original on 23 April 2022.

click "Nord Stream 2 – Environmental Impact Assessment, Denmark. South-Eastern Route. April 2019"

- ^ "Nord Stream 2 Public Hearing, presentation" (PDF). Nord Stream 2. 19 June 2019. p. 15. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 May 2021.

- ^ Ringstrom, Anna; Jacobsen, Stine (27 September 2022). "Sweden issues warning of two gas leaks on Nord Stream 1 pipeline". Reuters. Archived from the original on 27 September 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ Solsvik, Terje (29 September 2022). "Fourth leak found on Nord Stream pipelines, Swedish coast guard says". Reuters. Archived from the original on 29 September 2022. Retrieved 29 September 2022.

- ^ "Mysterious leaks hit Nord Stream pipelines linking Russia and Germany". Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 27 September 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ Nyheter, S. V. T.; Jönsson, Oskar; Wikén, Johan; Jensen Karlsson, Pontus (29 September 2022). "Explosionerna skedde nära svensk-polska elkabeln – specialister inkallade". SVT Nyheter (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 30 September 2022. Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- ^ Johan Zachrisson Winberg, Johan Wikén (4 October 2022). "Polenkabeln oskadd efter Nord Stream-läckorna" (in Swedish). SVT Nyheter. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

- ^ "Svenska marinen hade fartyg på plats före explosionerna". DN.SE (in Swedish). 30 September 2022. Archived from the original on 30 September 2022. Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- ^ "Marinen på plats dagarna före explosionerna". Omni (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 30 September 2022. Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- ^ "Danes: Nord Stream 2 pipeline seems to have stopped leaking". Associated Press. 1 October 2022. Archived from the original on 1 October 2022. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- ^ "Nord Stream 1 har slutat att läcka gas". Sveriges Radio. 2 October 2022. Archived from the original on 2 October 2022. Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- ^ "Kein Gasaustritt mehr aus Pipeline-Lecks?". Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (in German). 2 October 2022. Archived from the original on 3 October 2022. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- ^ a b "Pressure drop on both strings of the gas pipeline (update)". Nord Stream AG. 27 September 2022. Archived from the original on 27 September 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ "European leaders blame Russian 'sabotage' after Nord Stream explosions". The Washington Post. 27 September 2022. Archived from the original on 27 September 2022. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- ^ Stokel-Walker, Chris (3 October 2022). "Here's how the Nord Stream gas pipelines could be fixed". MIT Technology Review. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f Bennetts, Marc (2 February 2023). "Who attacked the Nord Stream pipelines?". The Times. London. Retrieved 2 February 2023.

- ^ a b c "Regeringen om gasläckagen: "Troligen fråga om ett sabotage"" (in Swedish). Sveriges Television. 27 September 2022. Archived from the original on 1 October 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ "Dansk ekspert: Eksplosion målt ved Bornholm svarer til en større bombe fra Anden Verdenskrig" (in Danish). Danmarks Radio. 27 September 2022. Archived from the original on 27 September 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ "Nord Stream leaks: Sabotage to blame, says EU". BBC. 28 September 2022. Archived from the original on 28 September 2022. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- ^ "NATO calls Nord Stream leaks acts of sabotage". Reuters. 28 September 2022. Archived from the original on 28 September 2022. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- ^ Ringstrom, Anna; Jacobsen, Stine (27 September 2022). "Gas leaks in Russian pipelines to Europe stoke sabotage fears". Reuters. Archived from the original on 27 September 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ "Kremlin: sabotage cannot be ruled out as reason for Nord Stream damage". Reuters. 27 September 2022. Archived from the original on 27 September 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ "Nord Stream: Ukraine accuses Russia of pipeline terror attack". BBC News. 27 September 2022. Archived from the original on 27 September 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ "Huge Nord Stream pipeline leaks could be sabotage, says Danish PM". POLITICO. 26 September 2022. Archived from the original on 27 September 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ ""Alles spricht gegen einen Zufall": Nord-Stream-Pipelines könnten durch Anschläge beschädigt worden sein". Der Tagesspiegel Online (in German). ISSN 1865-2263. Archived from the original on 27 September 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ a b "Nord-Stream-Pipelines: Keine gemeinsamen Ermittlungen". Tagesschau (in German). 14 October 2022. Retrieved 14 October 2022.

- ^ Burgess, Matt. "'Dark Ships' Emerge From the Shadows of the Nord Stream Mystery". Wired. Retrieved 13 November 2022.

- ^ "Polisen utreder sabotage av Nord Stream". Sveriges Radio. 27 September 2022. Archived from the original on 27 September 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ "Gassen fosser ud i Østersøen, og det er "næppe tilfældigt": Det ved vi om de tre læk, og det mangler vi svar på" (in Danish). Altinget. 27 September 2022. Archived from the original on 30 September 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ "Mette Frederiksen: Myndigheder vurderer, at lækager var bevidst sabotage" (in Danish). Danmarks Radio. 27 September 2022. Archived from the original on 27 September 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ "Russia May Use Nord Stream Aftermath to Cause More Trouble".

- ^ "World War 2 explosives hinder Nord stream pipeline leak investigation". Al Arabiya English. 13 October 2022.

- ^ Lehto, Essi; Ringstrom, Anna (7 October 2022). "'Gross sabotage': Nord Stream investigation finds evidence of detonations, Swedish police say". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

- ^ "Swedish probe of Nord Stream leaks points to 'serious sabotage'". Al Jazeera. 6 October 2022. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

- ^ "Nord-Stream-Lecks: Bundesanwaltschaft leitet Ermittlungen ein" [Nord Stream Leaks: Federal Attorney Office initiates investigation]. Tagesschau (in German). 10 October 2022. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ "Russia Denounces Exclusion From Nord Stream Leaks Probe". The Moscow Times. 13 October 2022.

- ^ More, Rachel (14 October 2022). "Sweden Shuns Formal Joint Investigation of Nord Stream Leak, Citing National Security". U.S. News. Reuters. Retrieved 16 October 2022.

- ^ JARED GANS (18 November 2022). "Swedish say they found evidence of explosives in Nord Stream pipelines". The Hill.

- ^ "Första bilderna från sprängda gasröret på Östersjöns botten". www.expressen.se (in Swedish). 18 October 2022. Archived from the original on 18 October 2022.

(translation) Our underwater camera documents long tears in the seabed before it reaches the concrete-reinforced steel pipe torn apart in the suspected sabotage. At least fifty meters of the gas line appears to be missing after the explosion ... A deep grave in the seabed where the gas pipeline used to be

- ^ Oltermann, Philip (18 October 2022). "Nord Stream 1: first underwater images reveal devastating damage". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- ^ Inimicizie (2 October 2022). "Il sabotaggio di Nord Stream e gli strani avvenimenti della primavera 2021". Inimicizie (in Italian). Retrieved 24 October 2022.

- ^ Kelly, Lidia (21 February 2023). "Russia urges Sweden again to share Nord Stream probe findings". Reuters. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- ^ "Sabotage of gas pipelines a wake-up call for Europe, warn officials". Financial Times. 28 September 2022. Archived from the original on 28 September 2022. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- ^ a b "Russia says UK navy blew up Nord Stream, London denies involvement". Reuters. 29 October 2022. Retrieved 29 October 2022.

- ^ "First on CNN: European security officials observed Russian Navy ships in vicinity of Nord Stream pipeline leaks | CNN Politics". 29 September 2022. Archived from the original on 29 September 2022. Retrieved 29 September 2022.

- ^ "'Only Russia' could be behind Nord Stream leaks, says former German intel chief". Politico. 29 September 2022. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- ^ a b "Georgia tahtoi Natoon ja seuraavaksi posahtivat putket – länsi halusi Nord Streamin, vaikka Venäjä käytti kaasua aseenaan jo vuosia aiemmin". Yle (in Finnish). 2 October 2022. Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- ^ Harris, Shane; Hudson, John; Ryan, Missy; Birnbaum, Michael (21 December 2022). "No conclusive evidence Russia is behind Nord Stream attack". The Washington Post. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- ^ "CIA warned Berlin about possible attacks on gas pipelines in summer – Spiegel". Reuters. 27 September 2022. Archived from the original on 28 September 2022. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- ^ Sanger, David E. and Julian E. Barnes (28 September 2022). "CIA Warned Europe of Potential Attacks on Nord Stream Pipelines". New York Times.

- ^ a b "Sikorski skrytykowany za wpis, nie wycofał się. "Cieszy mnie paraliż Nord Stream; to dobre dla Polski"". Dziennik Gazeta Prawna (in Polish). 28 September 2022. Archived from the original on 28 September 2022. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- ^ Shalal, Andrea (8 February 2022). "If Russia invades Ukraine, there will be no Nord Stream 2, Biden says". Reuters. Retrieved 2 February 2023.

- ^ a b "Russia exploits Polish ex-FM's Nord Stream tweet in information warfare against West: report". Polski Radio. 3 October 2022.

- ^ Stöcker, Christian (2 October 2022). "Die Copy-Paste-Propaganda" [The Copy-Paste Propaganda]. Der Spiegel (in German). Retrieved 5 October 2022.

Am Ende wurde Nord Stream 2 schon zwei Tage vor dem eigentlichen Einmarsch auf Eis gelegt [...]. Und zwar ganz ohne Sprengsätze. Es war also genau das passiert, was Biden und Scholz angekündigt hatten.

- ^ "U.S. has much to gain from Nord Stream damage, Russia says at U.N." Reuters. 1 October 2022. Retrieved 20 October 2022.

- ^ Weber, Joscha (30 September 2022). "No proof of US sabotage of Nord Stream pipeline". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- ^ Zhang, Legu (7 October 2022). "China Lets Nord Stream Sabotage Gossip Run Wild". Polygraph.info. Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- ^ Midolo, Emanuele. "US bombed Nord Stream gas pipelines, claims investigative journalist Seymour Hersh". The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- ^ Seymour Hersh im Interview: Joe Biden sprengte Nord Stream, weil er Deutschland nicht traute, Berliner Zeitung

- ^ "US and Norway blew up the Nord Stream Pipelines: Seymour Hersh". Helsinki Times. 16 February 2023. Retrieved 16 February 2023.

- ^ Scheidler, Fabian. "US Blew Up Nord Stream Pipeline Because Ukraine War Wasn't Going Well for the West: Seymour Hersh". The Wire (India). Retrieved 16 February 2023.

- ^ Kaspark, Alex (10 February 2023). "Claim That US Blew up Nord Stream Pipelines Relies on Anonymous Source". Snopes. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ "White House says blog post on Nord Stream explosion 'utterly false'". Reuters. 8 February 2023.

- ^ Faulconbridge, Guy; Soldatkin, Vladimir (9 February 2023). "Kremlin says those behind Nord Stream blasts must be punished". Reuters.

- ^ reported, February 9, 2023, Bloomberg News

- ^ Klungtveit, Harald S. (10 February 2023). "Forsvaret ut mot «oppspinn» om Nord Stream-sprengningen: – De norske flyene har aldri vært i området". Filter Nyheter (in Norwegian Bokmål). Retrieved 15 February 2023.

- ^ Mazneva, Elena (27 September 2022). "European Gas Prices Jump After Damage to Idled Russian Pipelines". Bloomberg. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ Delfs, Arne; Mazneva, Elena; Shiryaevskaya, Anna (27 September 2022). "Germany Suspects Sabotage Hit Russia's Nord Stream Pipelines". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 27 September 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ "Pipeline Breaks Look Deliberate, Europeans Say, Exposing Vulnerability". New York Times. 27 September 2022. Archived from the original on 27 September 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ a b Eriksson, Mikael; Ljungkvist, Matilda (27 September 2022). "Kustbevakningen rycker ut till gasläckan: Fartyget klarar att gå in i ett gasmoln" (in Swedish). Sveriges Radio. Archived from the original on 27 September 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ "Dansk fregat sendes til Bornholm – bygget til at kæmpe i gas" (in Danish). Danmarks Radio. 27 September 2022. Archived from the original on 27 September 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ @vonderleyen (27 September 2022). "Spoke to @Statsmin Frederiksen on the sabotage action #Nordstream. Paramount to now investigate the incidents, get full clarity on events & why. Any deliberate disruption of active European energy infrastructure is unacceptable & will lead to the strongest possible response" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ "Norway to strengthen security at oil, gas installations". Reuters. 27 September 2022. Archived from the original on 3 October 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ a b "Gas flows stable via Yamal pipeline and Ukraine". Reuters. 29 September 2022. Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- ^ a b "Eastward gas flows via Yamal pipeline rise, flows via Ukraine stable". Reuters. 27 September 2022. Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- ^ "Gazprom says gas exports to Europe via Ukraine steady on Sunday". Reuters. 2 October 2022. Archived from the original on 3 October 2022. Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- ^ Chestney, Nina (29 September 2022). "Russia's Ukraine gas transit sanction threat a fresh blow for Europe". Archived from the original on 1 October 2022. Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- ^ "Russian gas transit volume in Ukraine in 2022, by route". Statista. Statista Research Department. 28 September 2022. Archived from the original on 3 September 2022. Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- ^ "Gazprom lowers pressure in undamaged part of Nord Stream 2 pipe, Denmark says". Reuters. 5 October 2022.

- ^ "Norway inspects Europipe II subsea gas link to Germany". Reuters. 7 October 2022.

- ^ "After Nord Stream blasts, NATO, EU vows to protect infrastructure" aljazeera.com. Accessed 11 January 2023.

- ^ "Eksperten om gasudslip: Klimapåvirkning den største effekt". Sveriges Radio. 27 September 2022. Archived from the original on 27 September 2022. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- ^ "Gasläckan kan vara stor – påverkar klimatet". Barometern. 27 September 2022. Archived from the original on 30 September 2022. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- ^ "Record methane leak flows from damaged Baltic Sea pipelines". ABC News. Archived from the original on 30 September 2022. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- ^ "The possible climate effect of the gas leaks from the Nord Stream 1 and Nord Stream 2 pipelines". Energistyrelsen. 29 September 2022. Archived from the original on 30 September 2022. Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- ^ a b Benshoff, Laura (4 October 2022). "The Nord Stream pipelines have stopped leaking. But the methane emitted broke records". NPR.

- ^ "Nord Stream gas leaks may be biggest ever, with warning of 'large climate risk'". TheGuardian.com. 28 September 2022.

- ^ "Forsvarets eksperter må ikke udtale sig om efterforskning af gaslækager: Her er, hvad vi ved". Danmarks Radio (in Danish). 3 October 2022.

- ^ Amundsen, Bård (29 September 2022). "Gasslekkasjen i Østersjøen: Målestasjon på Sørlandet har registrert ekstrem økning i mengden metan i lufta". forskning.no (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 29 September 2022. Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- ^ "Environmental impact of sabotage of the Nord Stream pipelines". www.researchsquare.com. 10 February 2023. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ "Nord Stream-eksplosioner hvirvlede gift fra fortiden op i Østersøen". DR (in Danish). 27 February 2023. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- 2022 disasters in Europe

- 2022 industrial disasters

- 2022 controversies

- 2022 in Sweden

- September 2022 events in Denmark

- September 2022 crimes in Europe

- Events affected by the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine

- Pipeline accidents

- Gas explosions

- Unsolved crimes in Europe

- Russia–European Union relations

- Bornholm

- History of the Baltic Sea

- Scholz cabinet