James Bond

James Bond, codename 007 is a fictional British agent[1] created in 1952 by writer Ian Fleming, featured in several novels and short stories. After Fleming's death in 1964, subsequent James Bond novels were written by Kingsley Amis (as Robert Markham), John Pearson, John Gardner, Raymond Benson and Charlie Higson. Moreover, Christopher Wood novelised two screenplays, while other writers have authored unofficial versions of the secret agent character.

Initially famed through the novels, James Bond is best known from the Eon Productions film series, twenty-one of which have been made as of 2007. The 22nd Bond adventure is currently in production. In addition there are two independent productions and one Fleming-licenced American television adaptation of the first novel. The Eon Productions films are generally described as the "official" films and, although its origin is unclear, this term is used throughout this article. Albert R. "Cubby" Broccoli and Harry Saltzman co-produced the official films until 1975, when Broccoli remained the sole producer until his death in 1996. Since 1995, Broccoli's daughter Barbara and stepson Michael G. Wilson have co-produced them.

From 1962 through 2006, six actors have portrayed James Bond in "official" films:

- Sir Sean Connery (1962–1967; 1971)

- George Lazenby (1969)

- Sir Roger Moore (1973–1985)

- Timothy Dalton (1987–1989)

- Pierce Brosnan (1995–2002)

- Daniel Craig (2006–present)

The "unofficial" (that is non-Eon) versions were subject to separate licensing from Fleming. In the first version, Barry Nelson straight-forwardly portrayed James Bond in an Americanised 1954 television episode adaptation of Casino Royale. In the second unofficial version, David Niven was James Bond in the Columbia Pictures spy spoof Casino Royale, in 1967. Moreover, Sean Connery reprised James Bond in the non-Eon film Never Say Never Again (1983), an updating of his own film, the fourth in the series, Thunderball of 1965.

The twenty-first official film, Casino Royale, with Daniel Craig as James Bond, premiered on 14 November 2006,[2] with the film going on general release in Asia and the Middle East the following day.[3] Notably it is the first Bond film to be released in China.

Broccoli's and Saltzman's family company, Danjaq, LLC has held ownership of the James Bond film series (through Eon), and maintained co-ownership with United Artists Corporation since the mid-1970s, when Saltzman sold his share of Danjaq to United Artists. As of 2007, Columbia Pictures and MGM/United Artists co-distribute the franchise.

In addition to the novels and films, James Bond is a prominent character in many computer and video games, comic strips and comic books, and has been subjected to many parodies.

Ian Fleming's creation and inspiration

Commander James Bond, CMG, RNVR is an agent of the British Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) (more commonly, MI6). He was created in February 1952, by British journalist Ian Fleming while on holiday at his Jamaican estate, Goldeneye. The hero, 'James Bond', was named after an American ornithologist, a Caribbean bird expert and author of the definitive field guide book Birds of the West Indies. Fleming, a keen birdwatcher, had a copy of Bond's field guide at Goldeneye. Of the name, Fleming once said in a Readers Digest interview "I wanted the simplest, dullest, plainest-sounding name I could find, 'James Bond' was much better than something more interesting, like 'Peregrine Carruthers'. Exotic things would happen to and around him, but he would be a neutral figure – an anonymous, blunt instrument wielded by a Government Department."[4]

Nevertheless, news sources speculated about real spies or other covert agents after whom James Bond might have been named. Although they are similar to Bond, Fleming confirmed none as the source figure, nor did Ian Fleming Publications nor any of Fleming's biographers, such as John Pearson or Andrew Lycett.

It has also been suggested that the name 'James Bond' originated in Toronto, Ontario, when British Naval Intelligence Commander Ian Fleming was invited by Sir William Stephenson (codename 'Intrepid'), to participate in the SOE subversive warfare training Syllabus at STS-103. Fleming had a private residence in Avenue Road, Toronto, Canada, because the training camp barracks was full. On Avenue Road, there was the St. James-Bond Church (Toronto), its address was 1066 Avenue Road, and the military building address was 1107 Avenue Road (Double ones 0 and 7, thus number 007). The building does not exist, but in its place is Marshall McLuhan Catholic Secondary School — erected by Bondfield Construction in 2001.

James Bond's parents are Andrew Bond, a Scotsman and Monique Delacroix, from Canton de Vaud, Switzerland; their nationalities were established in On Her Majesty's Secret Service. Fleming emphasised Bond's Scottish heritage in admiration of Sean Connery's cinematic portrayal, whereas Bond's mother is named after a Swiss fiancée of Fleming's; a planned, but unwritten, novel would have portrayed Bond's mother as a Scot. Ian Fleming was a member of a prominent Scottish banking family.[5] In his fictional biography of secret agent 007, John Pearson gave Bond's birthdate as 11 November (Armistice Day) 1920; however, there is no evidence of it in Fleming's novels. Fleming was inspired by the playboy and real secret agent Dušan Popov, a Serb double agent for the British and the Germans. Bond's family motto is Orbis non sufficit (The world is not enough). [6]

After completing the manuscript for Casino Royale, Fleming allowed his friend, the poet William Plomer (later his editor), to read it, who liked it and submitted it to Jonathan Cape, who did not like it as much. Cape finally published it in 1953 on the recommendation of Fleming's older brother Peter, an established travel writer.[citation needed]

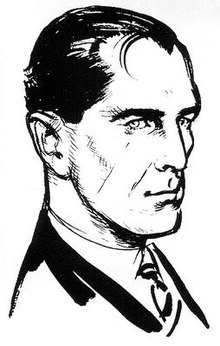

Most researchers agree that the James Bond is a romanticised version of Ian Fleming, himself a jet-setting womaniser. Both Fleming and Bond attended the same schools, preferred the same foods (scrambled eggs, coffee), maintained the same habits (drinking, smoking, wearing short-sleeve shirts), shared the same notions of the perfect woman (in terms of looks and style), and had similar naval career paths (both rising to the rank of naval Commander). They also shared similar height, hairstyle and eye colour. Bond's suave and sophisticated persona is based on that of a young Hoagy Carmichael. In Casino Royale, the anti-heroine Vesper Lynd remarks, "[Bond] reminds me rather of Hoagy Carmichael, but there is something cold and ruthless". Fleming did admit to being partly inspired by his service in the Naval Intelligence Division of the Admiralty, most notably an incident depicted in Casino Royale, when Fleming and Naval Intelligence Director Admiral Godfrey went on a mission to Lisbon en route to the United States during World War II. At the Estoril Casino (which harboured spies of warring regimes due to Portugal's neutrality), Fleming was 'cleaned out' by a "chief German agent" in a game of Chemin de Fer. Admiral Godfrey's account differs in that Fleming played Portuguese businessmen, whom Ian fantasised as German agents he defeated at cards. Moreover, references to 'Red Indians' in Casino Royale, (four times, twice in the final page) are to his own 30 Assault Unit.

Books

In February 1952, Ian Fleming began writing his first James Bond novel. At the time, Fleming was the foreign manager for Kemsley Newspapers, owners of The Sunday Times in London. Upon accepting the job, Fleming asked for two months yearly vacation in his contract; time spent writing in Jamaica. Between 1953 and his death in 1964, Fleming published twelve novels and one short-story collection (a second collection was published posthumously). Later, continuation novels were written by Kingsley Amis (as Robert Markham), John Gardner, and Raymond Benson, the last published in 2002. The Young Bond series of novels was begun in 2005, they are written by Charlie Higson.

Films

Top (From Left): Sean Connery, George Lazenby, Roger Moore

Bottom (From Left):Timothy Dalton, Pierce Brosnan, Daniel Craig

In the late 1950s, Eon Productions guaranteed the film adaptation rights for every 007 novel except for Casino Royale (those rights were recovered in the 1990s[7]) So in 1962, the first adaptation was made in Dr. No, that starred Sean Connery as 007. Connery starred in 5 more films, and after his initial portrayal, he was followed by George Lazenby (1 film), Roger Moore (7 films), Timothy Dalton (2 films), Pierce Brosnan (4 films) and Daniel Craig (currently 1 film). There have been currently 21 films, the latest one with a reboot in the series. The 22nd film is currently in production.

The twenty-one Bond films have grossed over $4 billion worldwide, being the second most successful film series ever (behind Star Wars).

The Eon films

| Title | Year | James Bond | Total Box Office | Budget |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dr. No | 1962 | Sean Connery | $59,600,000 | $1,000,000 |

| From Russia with Love | 1963 | $78,900,000 | $2,500,000 | |

| Goldfinger | 1964 | $124,900,000 | $3,500,000 | |

| Thunderball | 1965 | $141,200,000 | $11,000,000 | |

| You Only Live Twice | 1967 | $111,600,000 | $9,500,000 | |

| On Her Majesty's Secret Service | 1969 | George Lazenby | $87,400,000 | $7,000,000 |

| Diamonds Are Forever | 1971 | Sean Connery | $116,000,000 | $7,200,000 |

| Live and Let Die | 1973 | Roger Moore | $161,800,000 | $7,000,000 |

| The Man with the Golden Gun | 1974 | $97,600,000 | $7,000,000 | |

| The Spy Who Loved Me | 1977 | $185,400,000 | $14,000,000 | |

| Moonraker | 1979 | $210,300,000 | $34,000,000 | |

| For Your Eyes Only | 1981 | $195,300,000 | $28,000,000 | |

| Octopussy | 1983 | $187,500,000 | $27,500,000 | |

| A View to a Kill | 1985 | $152,400,000 | $30,000,000 | |

| The Living Daylights | 1987 | Timothy Dalton | $191,200,000 | $40,000,000 |

| Licence to Kill | 1989 | $156,200,000 | $42,000,000 | |

| GoldenEye | 1995 | Pierce Brosnan | $353,400,000 | $60,000,000 |

| Tomorrow Never Dies | 1997 | $346,600,000 | $110,000,000 | |

| The World Is Not Enough | 1999 | $390,000,000 | $135,000,000 | |

| Die Another Day | 2002 | $456,000,000 | $142,000,000 | |

| Casino Royale | 2006 | Daniel Craig | $593,145,012 | $130,000,000 |

| Bond 22 | 2008 | |||

| TOTALS | Films 1-22 | $4,355,700,000 | $848,200,000 |

* Figure as of February 2 (source - MI6.co.uk). This will increase as Casino Royale is still in cinema release in most countries.

Non-Eon Films, Radio and Television Programmes

In 1954, CBS paid Ian Fleming for the rights to adapt Casino Royale into a one hour television adventure as part of their Climax! series. A spoof of Casino Royale was made into a 1967 film spoof. A legal issue made Kevin McClory make a remake of Thunderball, returning Sean Connery as 007 in Never Say Never Again. MGM bought the name "James Bond" so future non-Eon productions are very unlikely.

| Title | Year | James Bond | Total Box Office | Budget |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Casino Royale — TV episode | 1954 | Barry Nelson | not applicable | unknown |

| Moonraker — Radio programme | 1956 | Bob Holness | not applicable | unknown |

| Casino Royale — Film spoof | 1967 | David Niven | $44,400,000 | $12,000,000 |

| Never Say Never Again | 1983 | Sean Connery | $160,000,000 | $36,000,000 |

Dealing with the changing actor

The Bond films rarely explicitly acknowledge the changes in cast members which have affected several of the recurring characters including Blofeld, Felix Leiter, M, Miss Moneypenny and Q. However, there are a few instances of reference to this, including:

- In the early scenes of the 1967 Casino Royale, David Niven's retired Bond berates M for giving his number and his name to a brash new agent; the description he gives fits Sean Connery's Bond.

- In On Her Majesty's Secret Service, when Tracy leaves George Lazenby's Bond alone on the beach, he complains, "This never happened to the other fellow." Similarly, a reference to Bond's return from holiday is included in the following film "Diamonds Are Forever," which featured Sean Connery's return to the role.

- In the non-EON film Never Say Never Again, M states that he has taken over the post from another individual.

- In GoldenEye, Valentin Zukovsky comments on how "the new M is a lady."

- In The World Is Not Enough (1999) Major Boothroyd's Q (played by Desmond Llewelyn) is preparing to retire, and introduces his successor, (jokingly referred to by Bond as "R"), played by John Cleese. Boothroyd has presumably retired by the time of Die Another Day (2002) as the character does not appear. In fact, Desmond Llewelyn had been killed in a car accident shortly after finishing the filming of The World is not Enough. Bond refers to Cleese's character first as Quartermaster, then as Q.

James Bond's influence on movies and television

James Bond has long been a household name and remains a huge influence within the spy genre. The Austin Powers series by writer and actor Mike Myers and other parodies such as Johnny English (2003), OK Connery, the "Flint" series starring James Coburn as Derek Flint, the "Matt Helm" movies starring Dean Martin, and Casino Royale (1967) are testaments to Bond's prominence in popular culture.

1960s TV imitations of James Bond such as I Spy, Get Smart, The Wild Wild West, and The Man from U.N.C.L.E. went on to become popular successes in their own right, the latter having enjoyed contributions by Fleming towards its creation: the show's lead character, "Napoleon Solo," was named after a character in Fleming's novel Goldfinger; Fleming also suggested the character name April Dancer, which was later used in the spin-off series The Girl from U.N.C.L.E. A reunion television movie, The Return of the Man from U.N.C.L.E. (1983), is notable for featuring a cameo by George Lazenby as James Bond in tribute to Fleming (for legal reasons, the character was credited as "JB").

The animated series US Acres (which aired with the Garfield cartoons) featured a "secret agent" episode with many Bond references. For instance, the one-letter names used to apply to the high-ranking MI6 individuals were parodied.

The Nickelodeon animated series Doug had a secret agent character named Smash Adams, who was obviously inspired by Bond. The character's theme music even resembled Monty Norman's classic 007 theme.

Nickelodeon's sketch comedy series All That once did a James Bond parody called Jimmy Bond.

In The Avengers, some time after the departure of the character Cathy Gale (played by actress Honor Blackman), the character of John Steed (played by Patrick Macnee) receives a Christmas card from her. He comments, "It's from Mrs Gale! I wonder what she's doing in Fort Knox?" – the intended destination for Honor Blackman's Pussy Galore in Goldfinger. In further coincidence, this comment is made to Emma Peel – played by Diana Rigg who would later appear as Tracy Bond in On Her Majesty's Secret Service. Macnee himself, a friend of Roger Moore, would later appear as Sir Godfrey Tibbett in A View to a Kill. Joanna Lumley (Purdey in the late Avengers serie) can also be seen in On Her Majesty's Secret Service in a little role with only one or two words.

A story line in The Beverly Hillbillies has Jethro (Max Baer, Jr.) forsaking his lifelong ambition to become a brain surgeon in favour of "double-naught spy." He outfits the Clampetts' truck with various Q-inspired gadgetry, none of which work according to plan.

In an apparent homage to the 'James Bond will return in...' credits, each of the season-ending episodes to date in the new (2005-present) series of Doctor Who has featured the ending credit, 'Doctor Who will return in...' followed by the title of the next episode (in each case, a Christmas special).[citation needed]

Similarly, four episodes of the TV series Arrested Development (For British Eyes Only, Forget-Me-Now, Notapusy and Mr. F) referenced the James Bond films. The spoofing of the Bond films is evident in the episode titles, vocal and instrumental music cues, and the gun barrel shot at the end of the episode accompanied by the subtitle "Michael Bluth will return in..."

George Lucas has said on various occasions that Sean Connery's portrayal of Bond was one of the primary inspirations for the Indiana Jones character, a reason Connery was chosen for the role of Indiana's father in the third film of that series.

In the episode "A Head in the Polls" of the animated television show Futurama, the robot Bender asks for a martini from a bartender, who pours the ingredients directly into a hole in the top of Bender's head. Bender then says, "Shaken, not stirred."

More of an imitation or homage (or possibly an unintentional parody), at the start of the French film "Taxi 3", after a Bond-style opening stunt sequence that end when a spy (played by Sylvester Stallone) is taken away by helicopter, a Bond-style theme music / opening credits sequence is performed before the main story proceeds.

On the popular Internet series, Red vs Blue, the character Donut is sent on a spy mission in the season 2 episode "Nut. Doonut.," and for around a quarter of the episode he makes references to James Bond and parodies some of the movie titles. The episode also has alternative titles based on Bond film titles.

Amiga computer game, James Pond.

Music

"The James Bond Theme" was written by Monty Norman and was first orchestrated by the John Barry Orchestra for 1962's Dr. No, although the actual authorship of the music has been a matter of controversy for many years. However, in 2001, Norman won £30,000 in libel damages from the British paper The Sunday Times, which suggested that Barry was entirely responsible for the composition.[8]

Barry did go on to compose the scores for eleven Bond films in addition to his uncredited contribution to Dr. No, and is credited with the creation of "007," used as an alternate Bond theme in several films, as well as the popular orchestrated theme "On Her Majesty's Secret Service." Both "The James Bond Theme" and "On Her Majesty's Secret Service" have been remixed a number of times by popular artists, including Art of Noise, Moby, Paul Oakenfold, and the Propellerheads. The British/Australian string quartet also named bond (purposely in lower case) recorded their own version of the theme, entitled "Bond on Bond."

Barry's legacy was followed by David Arnold, in addition to other well-known composers and record producers such as George Martin, Bill Conti, Michael Kamen, Marvin Hamlisch and Eric Serra. Arnold is the series' current composer of choice, and recently completed the score for his fourth consecutive Bond film, Casino Royale.

The Bond films are known for their theme songs heard during the title credits sung by well-known popular singers (which have included Tina Turner, Paul McCartney and Wings and Tom Jones, among many others). Shirley Bassey performed three themes in total. On Her Majesty's Secret Service is the only Bond film with a solely instrumental theme, though Louis Armstrong's ballad "We Have All the Time in the World," which serves as Bond and his wife Tracy's love song and whose title is Bond's last line in the film, is considered the unofficial theme. Perhaps one of the best known compositions is the title song to The Spy Who Loved Me, which is also known as Nobody Does It Better. Written by Marvin Hamlisch with lyrics by Carole Bayer Sager and sung by Carly Simon it features both lyric and orchestral arrangements in the credit sequences of the film. The main theme for Dr. No is the "James Bond Theme," although the opening credits also include an untitled bongo interlude, and concludes with a vocal Calypso-flavoured rendition of "Three Blind Mice" entitled "Kingston Calypso" that sets the scene. From Russia with Love also opens with an instrumental version over the title credits (which then segues into the "James Bond Theme"), but Matt Monro's vocal version also appears twice in the film, including the closing credits; the Monro version is generally considered the film's main theme, even though it doesn't appear during the opening credits. The only singer, to date, to appear within the titles is Sheena Easton, who sang the theme for For Your Eyes Only. The only singer of a title song to appear within the film itself as a character, to date, is Madonna, who appeared (uncredited) as a fencing instructor, Verity, as well as contributing the theme for Die Another Day. Chris Cornell performs "You Know My Name" in Casino Royale. He is the first male lead vocalist to perform a 007 song since a-ha in 1987 for "The Living Daylights." This is also the first Bond theme song since 1983's Octopussy to use a different title than the film. Although many of the theme songs were successful hits, the only theme song to hit #1 in the U.S. was Duran Duran's "A View to a Kill" which hit the top of the Billboard HOT 100 chart in 1985.

In 1998, Barry's music from You Only Live Twice was adapted into the hit song Millennium by producer and composer Guy Chambers for British recording artist Robbie Williams. The music video features Williams parodying James Bond, and references other Bond films such as Thunderball and From Russia With Love. It should also be noted that the video was filmed at Pinewood Studios, where most of the Bond films have been made.

Video games

In 1983, the first Bond video game, developed and published by Parker Brothers, was released for the Atari 2600, the Atari 5200, the Atari 800, the Commodore 64, and the Colecovision.[9] Since then, there have been numerous video games either based on the films or using original storylines.

Bond video games, however, didn't reach their popular stride until 1997's GoldenEye 007 by Rare for the Nintendo 64. Subsequently, virtually every Bond video game has attempted to copy GoldenEye 007's accomplishment and features to varying degrees of success – even going so far as to have a game entitled GoldenEye: Rogue Agent that had little to do with either the video game GoldenEye or the film of the same name. Bond himself plays only a minor role in which he is "killed" in the beginning during a 'virtual reality' mission, which served as a tutorial for the game.

Since acquiring the licence in 1999, Electronic Arts has released 8 games, 5 of which have original stories (i.e., not based on a film) including the popular Everything or Nothing, which broke away from the first-person shooter trend that started with GoldenEye 007 and went to a third-person perspective. It also featured well known actors including Willem Dafoe, Heidi Klum and Pierce Brosnan as James Bond, although several previous games have used Brosnan's likeness as Bond. In 2005, Electronic Arts released another game in the same vein as Everything or Nothing, this time a video game adaptation of From Russia with Love, which allowed the player to play as Bond with the likeness of Sean Connery. This was the second game based on a Connery Bond film (the first was a 1980s text adventure adaptation of Goldfinger) and the first to use the actor's likeness as agent 007. Connery himself recorded new voiceovers for the game, the first time the actor played Bond in 22 years.

In 2006 Activision secured the licence to make Bond-related games, currently shared with EA. The deal will become exclusive in September 2007.[10]

Comic strips and comic books

In 1957 the Daily Express, a newspaper owned by Lord Beaverbrook, approached Ian Fleming to adapt his stories into comic strips. After initial reluctance by Fleming who felt the strips would lack the quality of his writing, agreed and the first strip Casino Royale was published in 1958. Since then many illustrated adventures of James Bond have been published, including every Ian Fleming novel as well as Kingsley Amis's Colonel Sun, and most of Fleming's short stories. Later, the comic strip produced original stories, continuing until 1983.

Titan Books is presently reprinting these comic strips in an ongoing series of graphic novel-style collections; by the end of 2005 it had completed reprinting all Fleming-based adaptations as well as Colonel Sun and had moved on to reprinting original stories.

Several comic book adaptations of the James Bond films have been published through the years, as well as numerous original stories.

Bond characters

The James Bond series of novels and films have a plethora of allies and villains. Bond's superiors and other officers of the British Secret Service are generally known by letters, such as M and Q. In the novels (but not in the films), Bond has had two secretaries, Loelia Ponsonby and Mary Goodnight, who in the films typically have their roles and lines transferred to M's secretary, Miss Moneypenny. Occasionally Bond is assigned to work a case with his good friend, Felix Leiter of the CIA. In the films, Leiter appeared regularly during the Connery era, only once during Moore's tenure, and in both Dalton films; however, he was only played by the same actor twice. Absent from the Brosnan era of films, Felix returned in Craig's first James Bond film Casino Royale in 2006.

Bond's women, particularly in the films, often have double entendre names, leading to coy jokes, for example, "Pussy Galore" in Goldfinger (a name invented by Fleming), "Plenty O'Toole" in Diamonds Are Forever, and "Xenia Onatopp" (a villainess sexually excited by strangling men with her thighs) in GoldenEye.

Throughout both the novels and the films there have only been a handful of recurring characters. Some of the more memorable ones include Bill Tanner, Rene Mathis, Felix Leiter, Jack Wade, Jaws and recently Charles Robinson.

Vehicles and gadgets

Exotic espionage equipment and vehicles are very popular elements of James Bond's literary and cinematic missions; these items often prove critically important to Bond removing obstacles to the success of his missions.

Fleming's novels and early screen adaptations presented minimal equipment such as From Russia with Love's booby-trapped attaché case; in Dr. No, Bond's sole gadgets were a Geiger counter and a wristwatch with a luminous (and radioactive) face. The gadgets, however, assumed a higher, spectacular profile in the 1964 film Goldfinger. The film's success encouraged further espionage equipment from Q Branch to be supplied to 007. In the opinion of many critics and fans, some Bond films have included too many outlandish gadgets and vehicles, such as 1979's science fiction–oriented Moonraker and 2002's Die Another Day, in which Bond's Aston Martin could actually become invisible thanks to a technology Q refers to as adaptive camouflage. Since Moonraker, subsequent productions struggled with balancing gadget content against the story without depicting a technology-dependent man, to mixed results.

Bond's most famous car is the silver grey Aston Martin DB5 seen in Goldfinger, Thunderball, GoldenEye, Tomorrow Never Dies and Casino Royale. The films have used a number of different Aston Martin DB5s for filming and publicity; one of them was sold in January 2006 at an auction in Arizona for $2,090,000 (USD) to an unnamed European collector. That specific car was originally sold for £5,000 in 1970.[11]

In Fleming's books, Bond had a penchant for "battleship grey" Bentleys, while Gardner awarded the agent a modified Saab 900 Turbo nicknamed the Silver Beast and later a Bentley Mulsanne Turbo.

In the James Bond films, Bond has been associated with several well-known watches usually outfitted with high-tech features not found on the production models. Perhaps the most famous of these is the Rolex Submariner, which appeared during the Sean Connery films. Roger Moore's James Bond was fond of Seiko quartz watches. Pierce Brosnan's and Daniel Craig's James Bonds were both devotees of Omegas. The selection of James Bond's watch has been a matter of both style and finance, as product placement agreements with the watch manufacturers have frequently been arranged.

Bond's weapon of choice in the beginning of Dr. No is a Beretta in 6.35mm Browning caliber, also called "Lilliput", later replaced by the German made Walther PPK in 7.65mm Browning. The PPK was used in every subsequent film and became his signature weapon until the ending of Tomorrow Never Dies, when Bond required extra fire power and upgraded to the Walther P99. He used the pistol in The World Is Not Enough and Die Another Day, and continued using it in Casino Royale.

Locations

- Both Thunderball (1965) and Casino Royale (2006) were filmed at the casino resort on Paradise Island in the Bahamas.

- The Man With The Golden Gun (1974) was filmed in Bangkok and Phang Nga Bay in Thailand. The island in Pha Nga which is featured in the movie is a popular tourist destination, and has been nicknamed "James Bond Island" due to this association.

Other

- German disco group Dschinghis Khan performed a song called "James Bond' on their 1982 album Helden, Schurken und der Dudelmoser.[12]

- English rock group Placebo performed a song called "Miss Moneypenny" on their 1997 single "Nancy Boy"

- Swiss rock group Tunnelkid performed a song called "007“ on their 2006 album "Hang Me Now or Shoot Me Later"

- Swiss rock group Blotch performed a song called "Roger Moore" on their 2004 album "Passion, Love and Hurt"

- Desmond Dekker & the Aces had a UK Top 10 hit with the single "007" in 1967.

- On their second album "More Specials", released in 1980, The Specials closed side 1 with the track "Sock It To 'Em, J.B." Taking the song title at face value, the obvious musical JB inspiration is James Brown. However as the lyric name checks all the pre-1980 movies, inspiration for the track lies elsewhere.

- Kanye West and Jay-Z collaborate on Diamonds From Sierra Leone, a song about the atrocities in Sierra Leone, but samples the theme from Diamonds Are Forever.

- Two disco versions of the James Bond theme were released: one by the Biddu Orchestra called "James Bond Disco Theme" in 1978, and one by Marvin Hamlisch called "Bond '77" in 1977. The latter was composed for The Spy Who Loved Me.

References

- ^ In Fleming's first novel, Casino Royale, he refers to Bond as an agent.

- ^

"Stars out for Bond royal premiere". BBC. Retrieved 2006-11-15.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Casino Royale - Worldwide release dates". Sony Pictures. Retrieved 2006-10-25.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Chancellor, Henry (2005). James Bond: The Man and His World. John Murray. ISBN 0-7195-6815-3.

- ^ http://salon.com/books/feature/2006/11/25/fleming/

- ^ Biography of the Literary James Bond

- ^ Bond, from the beginning?

- ^ "Monty Norman sues for libel". Bond theme writer wins damages. Retrieved March 9.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "James Bond Games: James Bond 007". Retrieved 2007-03-12.

- ^ Fritz, Ben (2006-05-03). "Action traction: Bond, Superman games on the move". Variety. Retrieved 2006-07-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Aston Martin DB5 auction". James Bond car sold for over £1m. Retrieved February 8.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ swisscharts.com

- General references

- Amis, Kingsley (1965). The James Bond Dossier. Jonathan Cape.

- Benson, Raymond (1984). The James Bond Bedside Companion. Dodd, Mead. ISBN 1-4011-0284-0.

- Chapman, James (1999). Licence To Thrill: A Cultural History Of The James Bond Films. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 1-86064-387-6.

- Cork, John (2002). James Bond: The Legacy. Boxtree/Macmillan. ISBN 0-8109-3296-2.

- Lindner, Christoph (2003). The James Bond Phenomenon: A Critical Reader. Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-6541-0.

- Fleurier, Nicolas (2006). James Bond & Indiana Jones. Action figures. Histoire & Collections. ISBN 2-35250-005-2.

- Winder, Simon (2006). The Man Who Saved Britain. Picador. ISBN 0-330-43954-5.

- "Charlie Higson interview with CommanderBond.net". The Charlie Higson CBn Interview. Retrieved February 23.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - Bond franchise Box Office numbers [1], Casino Royale Box Office numbers (1967), Box Office numbers + Inflation

- Inside Camp X by Lynn Philip Hodgson, with a foreword by Secret Agent 'Andy Durovecz (2003) - ISBN 0-9687062-0-7

See also

- James Bond (character)

- Inspirations for James Bond

- James Bond (novels)

- James Bond Pun

- MI6.co.uk

- 9007 James Bond (Asteroid named after the character)

- James Bond Ultimate Edition DVD

- Pinewood Studios

External links

- Official sites

- James Bond Official Website

- Ian Fleming Publications Official Website

- Young Bond Official Website

- Pinewood Studios - home of Bond

- Pinewood Studios online store

- Fan sites

- Bondpedia - the main James Bond encyclopedia. Main wiki-based James Bond fan encyclopedia.

- 007 Bond Supplement

- 007James - The Site's Bond, James Bond

- 007 Magazine

- 30 Commando Assault Unit - Ian Fleming's 'Red Indians'

- Absolutely James Bond

- BondMovies.com

- CommanderBond.net

- James Bond Research

- Licensed to Kill - The Ultimate James Bond Community Fan Site

- MI6.co.uk

- The Bond Photo Page

- Universal Exports - The Home of James Bond, 007

- The Young Bond Dossier