Burma campaign

| Burma Campaign | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of WWII | |||||||

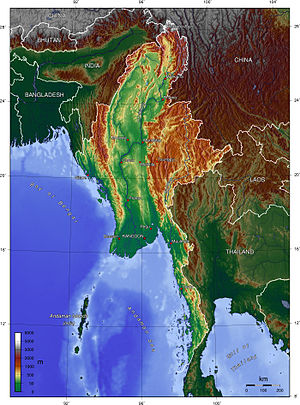

Geography of Burma | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

File:Imperial-India-Blue-Ensign.svg India |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Louis Mountbatten William Slim |

Masakazu Kawabe Hyotaro Kimura Subhash Chandra Bose Aung San | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

The Burma Campaign was a campaign in the South-East Asian Theatre of World War II. It was fought primarily between British India, Chinese and American forces against the Empire of Japan and its auxiliary, the Indian National Army.

Initial Japanese successes

See the South-East Asian Theatre and the Pacific War for a details on the initial Japanese successes including the fall of Hong Kong, the Battle of Malaya and the fall of Singapore.

Japanese capture of Rangoon

In Burma, the Japanese attacked in the middle of January 1942. Their initial attack was at Victoria Point which was expected and not contested. The second attack was a small probing raid directed at a police station in southern Tenasserim. The raid was repulsed. The Japanese then launched large overland attacks aimed at airfields at Tavoy and Mergui in the southern province of Tenasserim, which were difficult to defend and reinforce. Burma Army HQ had been ordered to hold these outposts based on the value of the airfields in the defence of Malaya. The Japanese forced their way over the steep and jungle-covered Tenasserim Range, and attacked Tavoy on January 18. The defenders, a mixed force comprising the 6th Burma Rifles and the 3rd Burma Rifles, were overwhelmed and forced to evacuate the town in disorder. Mergui was evacuated before it was attacked.

Rangoon was the major port in Burma, and with it, the Allies had many advantages of supply. It had at first been defended from air attacks relatively successfully, with the small RAF forces reinforced by a squadron of the American Volunteer Group, better known as the Flying Tigers. But the majority of the airfields were between Rangoon and the Japanese advance so, as the Japanese gained use of the airfields in Tenasserim, the amount of warning the Rangoon airfields could get of attack decreased, and they became more and more untenable.

On January 22 1942 the Japanese 55th Division began the main attack westward from Rahaeng in Thailand across the Kawkareik Pass. The Indian 17th Division guarding this approach was hastily formed and badly trained, and retreated westward. Moulmein at the mouth of the Salween River was garrisoned by a brigade-sized unit. It was ordered that Moulmein be held in spite of it being a terrible position. The brigade holding the town was squeezed into a progressively tighter perimeter. It eventually retreated over the Salween River by ferry on January 31 after abandoning a large amount of supplies and equipment. Part of the force was left behind in Moulmein and had to swim the river.

The Indian 17th Division attempted to hold a variety of fallback lines, but there were simply not enough troops to hold any sort of line. The Division gradually fell back toward the Sittang River in general disorder. At the river, a variety of incidents such as a vehicle breaking through the bridge deck led to continuous delays in getting the division over the river. There were also allegedly incidents of accidental attacks by the RAF on the retreating troops. The slow pace of the retreat allowed the Japanese to start harassment operations which slowed the retreat still further. Japanese parties eventually infiltrated through and around the British troops to the Bridge itself. The defence of the Bridge was poorly organized and the small Japanese parties eventually threatened to capture it. Eventually, in a decision that would forever after be controversial, the commander of the division blew the bridge on February 22 with most of the division left on the other side. The men on the other side made their way across as best they could either swimming or in improvised rafts. But what reached the other side of the river was essentially a wrecked force which had lost all its equipment.

Though the Sittang River was in theory a strong defensive position, the allied forces were simply no longer numerically strong enough to prevent the Japanese from infiltrating through their lines. As soon as a defensive line was created, small Japanese parties would be found setting up roadblocks behind it resulting in further retreats. Attacks by forces including the British 7th Armoured Brigade might be locally successful, but could not stop the overall Japanese advance. On March 7, the military evacuated Rangoon after implementing what they described as a "scorched earth" plan for denial. The port was destroyed and the oil terminal was blown up. As the British departed, the city was on fire. Its garrison broke through a Japanese roadblock on their line of retreat northward due to an error on the part of the Japanese commander. (Otherwise, the Japanese might have captured General Harold Alexander and much of the rest of Burma Army.)

Japanese advance to the Indian frontier

After the fall of Rangoon, the Allies decided to make a stand in the north of the country (Upper Burma). It was hoped that the Chinese forces which had entered the country in large numbers could stabilize a front running through central Burma. Supplies were generally not an issue. Much war material had been evacuated from Rangoon including material originally meant for shipment to China, rice was plentiful and the oilfields in central Burma were still intact.

The Allies hoped that the Japanese advance would slow; instead, it gained speed. The Japanese reinforced their two divisions in Burma with two more transferred from Malaya after the fall of Singapore. They also brought in large numbers of captured British trucks and other vehicles, which allowed them to move supplies rapidly, and also use Motorized infantry columns, particularly against the Chinese forces. The Japanese were also aided, or at least the Allies were harassed, by the rapidly expanding Burma Independence Army. The Allies were also to be hampered by large numbers of refugees (mostly Indian civilians) and the progressive breakdown of the civil government in the areas they held.

Burma Army's headquarters arrangements had been thrown into disarray. It was eventually decided to form "Burcorps" or 1st Burma Corps as an operational command. "Burcorps" and its leadership proved no more effective than the previous leadership in Burma. It was gradually pushed northward towards Mandalay. 1st Burma Division was encircled and trapped in the blazing oilfields at Yenangyaung, and although it was rescued by counterattacks, it lost almost all its equipment and its cohesion. Meanwhile, the Chinese armies were shattered by strong Japanese attacks. With the effective collapse of the entire defensive line, there was little choice left other than an overland retreat to India.

The retreat was conducted in horrible circumstances. Starving refugees, disorganised stragglers, and the sick and wounded clogged the primitive roads and tracks leading to India. Most of Burma Corps's remaining equipment was lost at Kalewa, although the troops escaped a Japanese attempt to trap them east of the Chindwin River. The Corps managed to make it most of the way to Imphal, in Manipur in India before the Monsoon broke in May 1942. There, they found themselves living out in the open during the peak of the Monsoon in extremely unhealthy circumstances. The army authorities in India were very slow to respond to the needs of the men.

The Chinese troops committed by Chiang Kai-shek (the Fifth, Sixth and Sixty-sixth Armies, each with the strength of a division but not necessarly a British level of equipment) also retreated. Some fell back across the River Salween into the Chinese province of Yunnan. Others were cut off and made their way in a completely disorganized manner to India where they were put under the command of the American General Joseph Stilwell. After recuperating they were re-equipped and retrained by American instructors.

Thai Army enters Burma

In accordance with the Thai military alliance with Japan that was signed on December 21, 1941, the leading elements of the Thai Phayap Army crossed the border into the Shan States on May 10, 1942. At one time in the past the area had been part of the Ayutthaya kingdom. The boundary between the Japanese and Thai operations was generally the Salween. However, that area south of the Shan States known as Karenni States, the homeland of the Karens, was specifically retained under Japanese control.

Three Thai infantry and one cavalry division, spearheaded by armoured reconnaissance groups and supported ably by the air force, started their advance on May 10, and engaged the retreating Chinese 93rd Division. Kengtung, the main objective, was captured on May 27. Renewed offensives in June and November drove the Chinese back into Yunnan.

At the end of the war, the Shan States were abandoned and reoccupied by the Chinese.

Allied setbacks, 1942 - 1943

Operations in Burma over the remainder of 1942 and in 1943 were a study of military frustration for the Allies. Britain could only maintain three active campaigns, and immediate offensives in both the Middle East and Far East proved impossible through lack of resources. The Middle East was accorded priority, being closer to home and in accordance with the "Germany First" policy in London and Washington.

The Allied buildup was also hampered by the disordered state of Eastern India at the time. There were violent "Quit India" protests in Bengal and Bihar, which required large numbers of British troops to suppress. There was also a disastrous famine in Bengal, which may ultimately have led to 3 million deaths through starvation, disease and exposure. Although the immediate cause was a typhoon which devastated large areas in mid-1942, the loss of rice normally imported from Burma and Allied demands for exported rice in other theatres reduced the reserves of food available for relief, while the dislocation caused by sporadic Japanese bombing, and corruption and inefficiency in the government of Bengal prevented any proper distribution of aid, or other drastic measures being taken.

In such conditions of chaos, it was difficult to improve the inadequate lines of communication to the front line in Assam, or make use of local industries for the war effort.

First Arakan campaign

Nevertheless, two operations were mounted during the 1942-1943 dry season. The first was a small scale offensive into the Arakan region of Burma. The Arakan is a coastal strip along the Bay of Bengal, crossed by numerous rivers. The First Arakan offensive aimed to reoccupy the Mayu peninsula and Akyab Island, which had an important airfield. Beginning on December 21 1942, Indian 14th Infantry Division advanced to Donbaik, only a few miles from the end of the peninsula. Here they were halted by a small Japanese force which occupied nearly impregnable bunkers. Indian and British troops made repeated frontal assaults without armoured support, and were thrown back with heavy casualties.

Meanwhile, Japanese reinforcements arrived from Central Burma. Crossing rivers and mountain ranges which the Allies had declared to be impassable, they hit 14th Division's exposed left flank on April 3 1943 and overran several units. It was eventually decided to hold a defensive line south of the town of Buthidaung. But the units were unable to hold the line and were forced to abandon much equipment and fall back almost to the Indian frontier. Irwin, being in overall command, was dismissed in part as a result of this disaster.

First Chindit expedition

The second action was much more controversial; that of the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade, better known as the Chindits. Under the command of Major General Orde Wingate, the Chindits marched deep behind enemy lines with an initial aim of cutting the main north-south railway in Burma. The operation had originally been conceived as part of a much larger coordinated offensive, which had to be aborted due to lack of supplies and shipping. Almost all of the original reasons for mounting the Chindit operation were then invalid. Nevertheless, it was mounted anyway.

Some 3,000 men entered Burma in many columns. They did cause damage to the communications of the Japanese in northern Burma cutting the railway for possibly two weeks. However, they suffered heavy casualties; 818 killed, wounded or missing, 27% of the original force. Those that did return were wracked with disease and quite often in dreadful physical condition. Though the operational results can be questioned, the Chindits proved that British and Indian soldiers could live, move and fight as effectively as the Japanese in the jungle, and this aspect of the campaign was used to great propaganda effect, countering the impression created after the battles of early 1942 that the Japanese could not be beaten in the Jungle. It was also said by the Japanese commanders after the war that the Japanese in Burma decided to take the offensive, rather than adopt a purely defensive stance, as a direct result of the Chindit operation.

Turning point

Rival plans

Allied plans

In August 1943 the Allies decided to create South East Asia Command (SEAC) a new combined command responsible for the South-East Asian Theatre. With the decision came a new sense of purpose and in November, when SEAC took over responsibility for Burma, the British Fourteenth Army was ready to take the offensive. The Allied supply lines were improving; by October 1944 capacity on the North-East Indian Railways had been raised to 4,400 tons a day from 600 tons a day at the start of the war. By 1944 the RAF had gained Air superiority and this allowed the Allies to employ new tactics.

SEAC had to accommodate several rival plans. Initially, the new Commander-in-Chief favoured amphibious landings. The first of these was to be on the Andaman Islands (Operation "Pigstick"). However, the landing craft initially assigned were recalled to Europe in preparation for the Normandy Landings. Even a limited amphibious move in support of a renewed offensive in the Arakan was abandoned.

Orde Wingate had gained approval for a greatly expanded Chindit force, rather against the wishes of Slim and others who felt that this was too great a drain on resources. Wingate had originally planned to capture an enemy airfield (at Indaw), which would then be garrisoned by a line infantry division. This second part of the plan for Special Force was later dropped.

Chiang Kai-shek had agreed to mount an offensive from the Yunnan. When the Andaman Island landings were cancelled, he claimed this was a breach of faith and cancelled the Yunnan offensive, although he later reinstated it.

The Allied plans for 1944 were reduced to: an offensive by Stilwell's Chinese troops from India; the Chindit operation in support of Stilwell; a renewed overland attack in the Arakan; and a rather ill-defined offensive across the Chindwin River from Imphal in support of the other operations.

Japanese plans

About the same time that SEAC was established, the Japanese also created Burma Area Army, which took under command the 15th Army and 28th Army.

By chance or design, the new commander of 15th Army, Renya Mutaguchi, had played a major part in many recent Japanese triumphs. He was keen to mount an offensive against India. Burma Area Army originally quashed this idea, but found that Southern Expeditionary Army HQ in Singapore was keen on it. When the staff at Southern Expeditionary Army were persuaded of the inherent dangers, they in turn found that Imperial Army HQ in Tokyo was in favour of Mutaguchi's plan.

To the Japanese, an unanswerable argument in favour of some sort of offensive strategy was that, merely to passively defend against the various Allied threats, they would need to reinforce Burma with as many divisions as they would need to mount the offensive. With misgivings at various headquarters (including those of some of the divisions which were to take part in the offensive), Operation U-G0, the attack on Imphal, was sanctioned.

Northern front 1943/44

Stilwell planned an attack on the North front to drive the Japanese out of the area, so that he could build the Ledo Road and get supplies overland to the National Chinese Army of Chiang Kai-Shek. The Chindits, now in divisional strength and designated Indian 3rd Infantry Division, were tasked with assisting Stilwell by disrupting the Japanese lines of supply to the northern front.

In October 1943 the Chinese 38th Division (led by Sun Li-jen) under Stilwell's command began the attack with an advance from Ledo towards Shinbwiyang, the intention being to carry the offensive on through to Myitkyina and Mogaung. As the forces under NCAC advanced so the Ledo Road advanced behind them. Whenever Chinese Divisions ran into Japanese strong points, Merrill's Marauders were used to outflank Japanese positions by going through the jungle. A technique which had served the Japanese so well earlier in the war before the Allies had learnt the arts of jungle warfare was now being used against them. At Walawbum, for example, if the Chinese 38th Division had been a little swifter and linked up with the Marauders it could have encircled the Japanese 18th Division.

Second Chindit Expedition 1944

In Operation Thursday the Chindits were to support Stilwell's advance by interdicting Japanese supply lines in the region of Indaw. On February 5, 1944, Bernard Fergusson's 16th Brigade left Ledo for Burma. They successfully avoided the Japanese and penetrated the Japanese rear areas. In early March three other brigades were flown into landing zones behind Japanese lines by the USAAF 1st Air Commando Group. Over the next two and a half months the Chindits were involved in many very heavy contacts with the Japanese.

On March 24, Wingate, the commander of the Chindits, was killed in an aircrash. His replacement was Brigadier Joe Lentaigne. On May 17 command of the Chindits passed from the Slim's Fourteenth Army to Stilwell's NCAC. The Chindits now moved from the Japanese rear areas to new bases closer to Stilwell's front, and were given additional tasks for which they were not equipped. Calvert's 77th Brigade captured Mogaung, but at the cost of 50 percent casualties. By the end of the campaign the Chindits had lost 1,396 killed and 2,434 wounded. Over half had to be hospitalised with a special diet afterwards.

Central Front

The Chinese forces on the Yunnan front mounted an attack starting in the second half of April, with nearly 40,000 troops crossing the Salween River on a 200 mile (300 km) front. Within a few days some twelve Chinese Divisions of 72,000 men, under the command of General Wei Li Huang, were attacking the Japanese 56th Division. The Japanese forces in the North were now fighting on two fronts: the Allies from the North West and the Nationalist Chinese from the North East.

While the Japanese offensive on the Central Front was being waged, Stilwell's forces continued to make gains. On May 17 1944, Merrill's forces captured the airfield at Myitkyina. If the Ledo Chinese troops who had been flown in that afternoon had attacked the town immediately, they could have overwhelmed the small garrison. But they did not and the opportunity was lost as the Japanese rapidly reinforced the town. Myitkyina did not fall until August 3rd. This long delay cost the allies many men, particularly amongst the Chindits who were forced to remain in the field to disrupt Japanese relief attempts far longer than had been planned. However, because of the deteriorating situation on the other fronts, the Japanese never looked like regaining the initiative on the Northern Fronts.

The capture of Myitkyina marked the end of the initial phase of Stilwell's campaign. It was the largest seizure of enemy-held territory to date in the Burma campaign and was primarily due to the Ledo Chinese divisions lead by Stilwell. The airfield at Myitkyina became a vital link in the air route over the Hump.

Southern front 1943/44

In Arakan, Indian XV Corps now commanded by Lieutenant General Philip Christison renewed the advance on the Mayu peninsula. Ranges of steep hills channeled the advance into three attacks; Indian 5th Infantry Division along the coast, Indian 7th Infantry Division along the Kalapanzin River, West African 81st Division along the Kaladan River.

5th Division captured the small port of Maungdaw on January 9, 1944. The Corps then prepared to capture two railway tunnels linking Maungdaw with the Kalapanzin valley. However, the Japanese struck first. A strong force from the Japanese 55th Division infiltrated Allied lines to attack the 7th Division from the rear, overrunning the Indian Divisional HQ.

Unlike previous occasions on which this had happened, the Allied forces stood firm against the attack, and were supplied from the air. In the Battle of the Admin Box from February 5 to February 23 1944, the Japanese concentrated on 7th Division's Administrative Area, defended mainly by service troops, but they were unable to deal with tanks supporting the defenders. Meanwhile, troops from 5th Division broke through the Ngakyedauk Pass to relieve the defenders of the box.

Although battle casualties were approximately equal, the overall result was a heavy Japanese defeat. Their infiltration and encirclement tactics had failed to panic Allied troops, and as the Japanese were unable to capture enemy supplies, they themselves starved.

Over the next few weeks, XV Corps offensive wound down as the Allies concentrated on the Central Front. After capturing the railway tunnels, XV Corps halted during the monsoon.

Central front 1943/44

Indian IV Corps, under Lieutenant-General Geoffrey Scoones, had pushed forward two divisions to the Chindwin River; Indian 17th Infantry Division to Tiddim and the Indian 20th Infantry Division to Tamu. Indian 23rd Infantry Division (which was 5000 men under establishment due to sickness) was in reserve at Imphal. There were indications that a major Japanese offensive was building. Slim and Scoones planned to withdraw and force the Japanese to fight with their logistics stretched beyond the limit. However, they misjudged the date on which the Japanese were to attack, and the strength they would use against some objectives.

The Japanese 15th Army (33rd Division, 15th Division and "Yamamoto Force"), under Lieutenant-General Renya Mutaguchi, planned to cut off and destroy the forward divisions of IV Corps, before capturing Imphal. The 31st Division would meanwhile isolate Imphal by capturing Kohima. Mutaguchi intended to exploit this victory by capturing the strategic city of Dimapur, in the Brahmaputra River valley. If this could be achieved, his army would be through the mountainous border region and the whole of North East India would be open to attack. Units of the Indian National Army were to take part in the offensive and raise rebellion in India. The capture of the Dimapur railhead would also sever the land communications to the airbases used to supply the Chinese over the Hump and cut off supplies to General Stilwell's forces fighting on the Northern Front.

The Japanese launched their troops across the Chindwin River on March 8. Scoones only gave his forward divisions orders to withdraw to Imphal on March 13. The Indian 20th Division withdrew without difficulty; the Indian 17th Division was cut off by the Japanese 33rd Division. From March 18 to March 25, thanks to air re-supply by the now highly experienced RAF and U.S Troop Carrier Command crews in their C-47 Dakotas, and assistance from the Indian 23rd Division, the 17th was able to fight its way back through four Japanese road blocks. The two divisions reached the Imphal plain on April 4. Meanwhile, Imphal had been left vulnerable to the Japanese 15th Division. The only force left covering the base, Indian 50th Parachute Brigade, was roughly handled at Sangshak by a regiment from the Japanese 31st Division on its way to Kohima. However, the diversionary attack launched by Japanese 55th division on The Southern Front, had already run out of steam. In late March Slim was able to move the battle-hardened "Ball of Fire" Indian 5th Division, including all their artillery, jeeps, mules and other materiel, by air from Arakan to the Central Front. The move was completed in only eleven days. Two brigades went to Imphal, the other (the Indian 161st Infantry Brigade) went to Dimapur from where it sent a detachment to Kohima.

While the Allied forces in Imphal were cut off and besieged, the Japanese 31st Division, consisting of 20,000 men under Lieutenant-General Kotoku Sato were able to advance up the Imphal–Dimapur road. It was at this point that the Japanese plan started to unravel. Instead of isolating the small garrison at Kohima and pressing on with his main force to Dimapur, Sato chose to concentrate on capturing the hill station. The Japanese records indicate that Sato (and Mutaguchi's other divisional commanders) had severe misgivings about 15th Army's plan. In particular, they thought the logistic gambles were reckless, and were unwilling to drive on objectives they thought unattainable.

The Battle of Kohima started on April 5 when the Japanese 31st Division started the siege. In the initial phase of the battle the Japanese tried to dislodge the defenders from their hill top redoubts. Fighting was very heavy around the District Commissioner's tennis court. This phase of the battle is often referred to as the Battle of the Tennis Court and is particularly significant as it was the turning point of the Burma Campaign. On April 18 the Indian 161 Brigade relieved the defenders, but the battle of Kohima was not over as the Japanese dug in and defended the positions they had captured.

A new formation HQ, the Indian XXXIII Corps under Lieutenant-General Montagu Stopford, now took over operations on this front. The British 2nd Infantry Division began a counter-offensive and by May 15, they had prised the Japanese off Kohima Ridge itself, although the Japanese still held dominating positions north and south of the main road to Imphal. More Allied troops were arriving at Kohima; the Indian 7th Division followed 5th Division from the Arakan; a motor infantry brigade reinforced 2nd Division; a brigade diverted from the Chindit operation cut Japanese 31st Division's supply lines. XXXIII Corps renewed its offensive in the middle of May.

The Battle of Imphal went badly for the Japanese during the month of April, as their attacks from several directions on the Imphal plain failed to break the Allied defensive ring. Slim and Scoones now began a counter-offensive against the Japanese 15th Division north of Imphal. Progress was slow. The monsoon had broken, and this made movement very difficult. Also, IV Corps was suffering some shortages. Although rations and reinforcements were delivered to Imphal by air, artillery ammunition was by now rationed. However, the Japanese were at the end of their endurance and with the monsoon season beginning, conditions would quickly become far worse. Neither 31st Division nor 15th Division had received adequate supplies since the offensive began, and their troops lacked proper food. During the rains, disease and other health related problems quickly multiplied among the Japanese as well. Lieutenant-General Sato had notified Mutaguchi that his division would withdraw from Kohima at the end of May if it was not supplied. Nevertheless, Sato did indeed begin to retreat, although an independent detachment from his division continued to fight delaying actions along the Imphal Road. Meanwhile, the units of 15th Division were wandering away from their positions to forage for supplies. Its commander, Lieutenant-General Masafumi Yamauchi (who was mortally ill) was dismissed but this could not affect matters. The leading troops of IV Corps and XXXIII Corps met at Milestone 109 on the Dimapur-Imphal road on June 22, and the siege of Imphal was raised.

Mutaguchi (and Kawabe) continued to order renewed attacks. 33rd Division (under a new forceful commander, Lieutenant-General Nobuo Tanaka), and Yamamoto Force made repeated efforts south of Imphal, but by the end of June they had suffered so many casualties both from battle and general sickness that they were unable to make any progress. The Imphal operation was finally broken off early in July, and the Japanese retreated painfully to the Chindwin River.

It was the largest defeat to that date in Japanese history. They had suffered 55,000 casualties, including 13,500 dead. Most of these losses were the result of disease, malnutrition and exhaustion. The Allies suffered 17,500 casualties. Mataguchi was relieved of his command and left Burma for Singapore in disgrace. Sato refused to commit Seppuku (hara-kiri) when handed a sword by Colonel Shumei Kinoshita, insisting that the defeat had not been his doing[1]. He was examined by doctors who stated that his mental health was such that he could not be court-martialled. (This was probably under pressure from Kawabe and Terauchi, who did not wish a public scandal).

From August to November, Fourteenth Army pursued the Japanese to the Chindwin River, and mopped up numbers of stragglers. Slim and his Corps commanders (Scoones, Christison and Stopford) were knighted by Wavell (the Viceroy of India) in a ceremony at Imphal in December.

British 1944-1945 offensives

The British launched a series of offensive operations back into Burma during late 1944 and the first half of 1945. Command of the British formations on the front was rearranged in November 1944. 11th Army Group was replaced with Allied Land Forces South East Asia and NCAC and XV Corps were placed directly under ALFSEA.

The Japanese also made major changes in their command. The most important was the replacement of General Kawabe at Burma Area Army by Hyotaro Kimura. Kimura threw Allied plans into confusion by refusing to fight at the Chindwin River. Recognising that most of his formations were weak and short of equipment, he withdrew 15th Army behind the Irrawaddy River (Operation BAN). 28th Army was to continue to defend the Arakan and lower Irrawaddy valley (Operation KAN), while 33rd Army would attempt to prevent the completion of the new road link between India and China by defending Bhamo and Lashio, and mounting guerilla raids (Operation DAN).

Southern Front 1944/45

In Arakan, as the monsoon ended, XV Corps resumed its advance on Akyab Island for the third year in succession. This time the Japanese were numerically far weaker, and had already lost the most favourable defensive positions. The Indian 25th Infantry Division advanced on Foul Point and Rathedaung at the end of the Mayu Peninsula, while the West African 81st Division and West African 82nd Division converged on Myohaung at the mouth of the Kaladan River. The Japanese evacuated Akyab Island on December 31 1944. It was occupied by XV Corps without resistance two days later.

The West African 82nd Division now attacked south along the coastal plain, while amphibious landings were made further south to capture the Japanese in a pincer movement. The first landings were made by a brigade of commandos, first ashore was No.42 Commando on the south-eastern face of the Myebon Peninsula on January 12 1945. Over the next few days the commandos and a brigade of the Indian 25th Division cleared the peninsula and in doing so denied the Japanese the use of the many waterways along the Arakan coast.

On January 22 No 3 Commando Brigade landed on the beaches at Daingbon Chaung led this time by No. 1 Commando. Having secured the beaches they moved inland and became involved in very heavy fighting with the Japanese. The following night a brigade of the 25th Division was landed in support. The fighting around the beachhead involved hand-to-hand fighting as the Japanese realising the danger threw all their available troops into the fight. It was not until the 29th that the allied forces managed to turn the tide of the battle and take the village of Kangaw. Meanwhile the forces on the Myebon Peninsula linked up with the 82nd Division fighting its way overland towards Kangaw. Caught between the 82nd and the forces already in Kangaw, the Japanese were forced to scatter leaving behind thousands of dead and most of their heavy equipment.

Following these actions, XV Corps operations were curtailed to release transport aircraft to support Fourteenth Army. With the coastal area secured the Allies were free to build sea-supplied airbases on the two offshore islands, Ramree Island and Cheduba. Cheduba, the smaller of the two islands, had no Japanese garrison, but the clearing of the small but typically tenacious Japanese garrison on Ramree took about six weeks (see Battle of Ramree Island). [2] [3]

Northern Front 1944/45

NCAC's operations were limited from late 1944 onwards by the need for Chinese troops on the main front in China. With their usual dismissive attitude, the American and British commanders attached the Chinese leadership for focusing on the defensive of Chinese cities and peoples rather than the defeat of the Japanese in Burma. In spite of these limitations, General Sultan was still able to resume his advance against the Japanese 33rd Army.

On his right, the British 36th Infantry Division, brought in to replace the Chindits, made contact with the Indian 19th Infantry Division near Indaw on December 10 1944, and Fourteenth Army and NCAC now had a continuous front. Meanwhile, three Chinese divisions and a US Force known as the "Mars Brigade" (which had replaced Merrill's Marauders) advanced slowly from Myitkyina to Bhamo. The Japanese resisted for several weeks, but Bhamo fell on December 15.

Sultan's forces made contact with Chiang's Yunnan armies on January 21 1945, and the Ledo road could finally be completed, although it was not yet secure. The Ledo road by this point in the war was also of uncertain value. It would not be completed soon enough to change the overall military situation in China. Chiang, to the annoyance of the British and Americans, ordered Sultan to halt his advance at Lashio, which was captured on March 7. As usual, the British and Americans refused to understand that Chiang had to balance the needs of China as a whole against fighting the Japanese in a British colony. By now, the Japanese lines of communication to the Northern front were about to be cut by Fourteenth Army, and they abandoned this front. From April 1, NCAC's operations stopped, and its units returned to China. 36th Division was withdrawn to India. A US-led guerrilla force, OSS Detachment 101, took over those responsibilities of NCAC which had associated with the American forces. On the British side, civil affairs and other units (such as CAS(B)) stepped in to take over the other responsibilities of NCAC. Northern Burma was partitioned into LOC areas by the military authorities.

Central Front 1944/45

Fourteenth Army made the main thrust into central Burma. It had IV Corps and XXXIII Corps under its command, with six infantry divisions, two armoured brigades and three independent infantry brigades. Logistics were the primary problem the advance faced. A carefully designed system involving large amounts of supply by air was introduced as well endless construction projects designed to improve the land route from India into Burma.

When it was realised that the Japanese had fallen back behind the Irrawaddy River, the plan was modified. Initially both corps had been attacking into the Shwebo Plain between the Chindwin and Irrawaddy rivers. Now, only XXXIII Corps would continue this attack, while IV Corps changed its axis of advance to the Gangaw Valley west of the Chindwin, aiming to cross the Irrawaddy close to Pakokku and then capture the main Japanese line of communication centre of Meiktila. Diversionary measures (such as dummy radio traffic) would persuade the Japanese that both corps were aimed at Mandalay.

The plan was completely successful. Allied air superiority and the thin Japanese presence on the ground meant that the Japanese were unaware of the strength of the force moving on Pakokku. During January and February, XXXIII Corps seized crossings over the Irrawaddy River near Mandalay. There was heavy fighting, which attracted Japanese reserves and fixed their attention. Late in February, Indian 7th Division, leading IV Corps, seized crossings at Nyaungu, near Pakokku. Indian 17th Division and 255th Indian Armoured brigade followed them across and struck for Meiktila.

Central Burma in the dry season is an open plain with sandy soil. The Indian 17th Division (which was now mechanized) and the armoured brigade could move rapidly and unhindered in this open terrain, apparently taking the staffs at the various Japanese headquarters by surprise with this blitzkrieg manoevre. They struck Meiktila on March 1, and captured it in four days, despite resistance to the last man. In an often-recounted incident, some Japanese soldiers crouched in trenches with aircraft bombs, with orders to detonate them when an enemy tank loomed over the trench.

The Japanese tried first to relieve the garrison at Meiktila, and then to recapture the town and destroy Indian 17th Division. Although a total of eight Japanese regiments were eventually involved, they were mostly weak in numbers and drawn from five separate divisions, so their efforts were not coordinated. 33rd Army HQ was assigned to take command in this vital sector, but was unable to establish proper control. The Indian 17th Division had been reinforced by two infantry brigades landed by air. British tanks and infantry continually sallied out of Meiktila to break up Japanese concentrations. By the end of the month the Japanese had suffered heavy casualties and lost most of their artillery, their chief anti-tank weapon. They broke off the attack and retreated to Pyawbwe.

While the Japanese were distracted by events at Meiktila, XXXIII Corps had renewed its attack on Mandalay. It fell to Indian 19th Division on March 20, though the Japanese held the former citadel which the British called Fort Dufferin for another week. The battle was extremely costly in that much of the historically and culturally significant portions of Mandalay, including the old royal palace were burned to the ground. A great deal was lost by the Japanese choice to make a last stand in the city itself. With the fall of Mandalay (and of Maymyo to its east), communications to the Japanese front in the north of Burma were cut, and the road link between India and China could finally be completed though far too late to matter much. The Japanese 15th Army was reduced to small detachments and parties of stragglers making their way east into the Shan States.

Race for Rangoon

Though the Allied force had advanced successfully into central Burma, from a supply point of view the capture of the port of Rangoon before the monsoon was seen as critically important. The overland route from India, while it was able to sustain the dry-season offensive, would not be able to fully meet the needs of the large army force and (as importantly) the food needs of the civilian population in the areas captured.

In the spring of 1945, the other factor in the race for Rangoon was the years of planning by the liaison organisation, Force 136, which resulted in a national uprising within Burma and the defection of the entire Burma National Army to the allied side. In addition to the allied advance, the Japanese now faced open rebellion behind their lines.

XXXIII Corps mounted Fourteenth Army's secondary drive down the Irrawaddy River valley, against stiff resistance from the Japanese 28th Army. IV Corps made the main attack, down the "Railway Valley", which was also followed by the Sittang River. They began by striking at the delaying position held by the remnants of Japanese 33rd Army at Pyawbwe. The Indian 17th Division and 255th Armoured Brigade were initially halted by a strong defensive position behind a dry chaung, but a flanking move by tanks and mechanized infantry struck the Japanese from the rear and shattered them.

From this point, the advance down the main road to Rangoon faced little organized opposition. At Pyinmana, the town and the bridge were seized before the Japanese could organise their defence. Japanese 33rd Army HQ was attacked here, and although Lieutenant-General Honda and his staff escaped, they could no longer control the remnants of their formations.

The Japanese 15th Army had reorganised in the Shan States and were reinforced by 56th Division. They were ordered to move to Toungoo to block the road to Rangoon, but a general uprising by Karen forces who had been organised and equipped by Force 136, delayed them long enough for the Indian 5th Division, now leading IV Corps, to reach the town first.

The Indian 17th Division took over the lead of the advance, and met Japanese rearguards north of Pegu, 40 miles (64 km) north of Rangoon, on April 25. Kimura had formed the various service troops, naval personnel and even Japanese civilians in Rangoon into the Japanese 105 Independent Mixed Brigade. This scratch formation used buried aircraft bombs, anti-aircraft guns and suicide attacks with pole charges to delay the British advance. They held the British off until April 30 and covered the evacuation of the Rangoon area.

Operation Dracula

The original conception of the plan to re-take Burma had seen XV Corps making an amphibious assault on Rangoon well before Fourteenth Army reached the capital, in order to ease supply problems. Lack of resources meant that Operation Dracula did not take place in its original form.

Slim feared that the Japanese would defend Rangoon to the last man through the monsoon, which would put Fouteenth Army in a disastrous supply situation. His lines of communication by land were impossibly long, and the troops relied on supplies ferried by aircraft to airfields close behind the leading troops. Heavy rain would make these airfields unusable, and curtail flying. He therefore asked for Dracula to be re-mounted at short notice.

However, Kimura had ordered Rangoon to be evacuated, starting on April 22. Many troops were evacuated by sea, although British submarines claimed several ships. Kimura's own HQ left by land. The Japanese 105 Independent Mixed Brigade, by holding Pegu, covered this evacuation.

On May 1, a Gurkha parachute battalion was dropped on Elephant Point, and cleared Japanese rearguards (or perhaps merely parties left behind and forgotten) from the mouth of the Rangoon River. The Indian 26th Infantry Division landed the next day and took over Rangoon, which had seen an orgy of looting and lawlessness similar to the last days of the British in the city in 1942.

The leading troops of the Indian 17th and 26th divisions met at Hlegu, 28 miles (45 km) north of Rangoon, on May 6.

Final operations

Following the capture of Rangoon, there were still Japanese forces to take care of in Burma, but it was effectively a large mopping up operation. A new army headquarters ,that of Twelfth Army was created from XXXIII Corps HQ to take control of the formations which were to remain in Burma. It took IV Corps under command.

The Japanese 28th Army, after withdrawing from Arakan and resisting XXXIII Corps in the Irrawaddy valley, had retreated into the Pegu Yomas, a range of low jungle-covered hills between the Irrawaddy and Sittang rivers. They planned to break out and rejoin Burma Area Army. To cover this breakout, Kimura ordered Honda's 33rd Army to mount a diversionary offensive across the Sittang, although the entire army could muster the strength of barely a regiment. On July 3, Honda's troops attacked British positions in the "Sittang Bend". On July 10, after a battle for country which was almost entirely under chest-high water, both the Japanese and the Indian 89 Brigade withdrew.

Honda had attacked too early. Sakurai's 28th Army was not ready to start the breakout until July 17. The breakout was a disaster. The British had captured the Japanese plans from an officer killed making a final reconnaissance, and had placed ambushes or artillery concentrations on the routes they were to use. Hundreds of men drowned trying to cross the swollen Sittang on improvised bamboo floats and rafts. Burmese guerillas and bandits killed stragglers east of the river. The breakout cost the Japanese nearly 10,000 men, half the strength of 28th Army. British and Indian casualties were barely a handful.

It has sometimes been argued that this slaughter so close to the end of the war was unnecessary. However, nobody in South East Asia Command was aware of the existence of the atomic weapons which would shortly force Japan to surrender unconditionally.

Fourteenth Army (now under Lieutenant General Miles Dempsey) and XV Corps had returned to India to plan the next stage of the campaign to re-take south east Asia. A new corps, the Indian XXXIV Corps, under Lieutenant-General Ouvry Roberts was raised and assigned to Fourteenth Army for further operations.

This was to be an amphibious assault on the western side of Malaya codenamed Operation Zipper. The dropping of the atomic bombs forestalled Zipper, but the operation was undertaken post-war as the quickest way of getting occupation troops into Malaya.

American contribution

The RAF were aided by a number of USAAF units from the Tenth and Fourteenth air forces. The American Volunteer Group (AVG) known as "Flying Tigers" were in the theatre before the war and the unit formed the core of the Fourteenth Air Force. Two other notable formations were the No. 490 Bomb Squadron USAAF nicknamed the "Burma Bridge Busters", (part of the 341 Bomb Group USAAF which also included the 11th, 22nd and 491st Bomb Squadrons) and 1st Air Commando Group which was created to support the Chindits. When the Chindits operation ended the 1st Air Commando Group, renamed the 1st Air Commando Force, stayed to support other units of the British Fourteenth Army.

The strategic need to keep open the supply routes to China dictated the Burma campaign. After the loss of the Burma Road, the British wanted to supply China via the Hump until they could recapture it. The American General Joseph Stilwell thought it better to build a new road through north Burma to the Burma Road close to the Chinese border. He prevailed and this influenced the conduct of the campaign. So that the Ledo Road could be built, he attacked the Japanese northern front with Merrill's Marauders, the Chindits and Chinese troops along the route of the new road. They cleared north Burma after heavy jungle fighting and the prolonged siege of Myitkyina.

The Allies increased the tonnage carried by the Northeast Indian Railways to three times their peacetime level. This was only made possible with the use of specialised American railroad units using American and Canadian locomotives.

For more details see the articles on Northern Combat Area Command and the China Burma India Theater.

RAF

Battle Honour: BURMA 1944-1945

- Qualification: For operations during the 14th Army's advance from Imphal to Rangoon, the coastal amphibious assaults, and the Battle of Pegu Yomas, August 1944 to August 1945.

Command structure

Allied command

Initially command problems beset the Burma campaign. Burma was swapped from command to command during the pre-war period and the early months of the war. It was never expected that the Japanese would invade Burma.

- 1937 Burma was politically separated from India and fully responsible for its own military forces.

- 1939 with the outbreak of war Burma forces were placed under British Chiefs of Staff, but financed out of Burmese taxes and locally administered.

- 1940 The Prime Minister and Cabinet decided on a policy of providing direct military assistance to China through Burma. Chinese troops would be trained in Burma as irregulars, war material would be sent into China through Burma and covert American Air units (the AVG) would be moved into China through Burma. The British authorities gave no consideration to adding to the defence of Burma based on these policies.

- November 1940 operational control was transferred to the recently formed Far East Command in Singapore, while administrative responsibility was divided between the Burma Government and the War Office in London, which now contributed to the defence budget of Burma.

- December 12 1941, when a Japanese attack was seen to be imminent Burma was handed back to India Command under the command of Commander-in-Chief (CinC) in India General Sir Archibald Wavell .

- From January 1 1941 Burma was operationally controlled by ABDACOM and administered from Delhi. The Supreme Commander of ABDACOM General Wavell (who had transferred from CinC, India), moved his command to Java on January 15 1942.

- On February 25, 1942 Wavell resigned as supreme commander of ABDACOM, handing control of the ABDA Area to local commanders. He also recommended the establishment of two Allied commands to replace ABDACOM: a south west Pacific command, and one based in India. In anticipation of this, Wavell had handed control of Burma to the India Command. On resigning from ABDACOM Wavell reassumed his previous position, as Commander-in-Chief, India.

The British commander in Burma, Lieutenant General Sir Thomas Hutton was removed from command shortly before Rangoon fell in March 1942. He was replaced by Sir Harold Alexander. Hutton became Alexander's chief of staff. The Burma 1st Division and Indian 17th Infantry Division at first had to be controlled directly by Burma Army headquarters, as there was no corps HQ. After the fall of Rangoon, Burma Corps Headquarters was created under Lieutenant General William Slim to control the forces that remained in Burma.

Cooperation with the Chinese proved difficult for several reasons. The American Liaison (Stilwell) was ill-tempered and lacked respect for either the British or the Chinese. Chiang Kai-Shek, the leader of Nationalist China, was more interested in fighting the Japanese in China than in attempting to save a disorganized British force in Burma. The Chinese Army also suffered from severe command problems, with important orders having to come directly from Chiang himself if they were to be obeyed. From the Chinese perspective, the Americans and the British were trying to take over command of the Chinese armies to use them for their own purposes. These problems were never completely satisfactorily resolved. They were partially resolved by the Americans in the aftermath of the 1942 campaign re-equipping, re-training and taking over the leadership of the Chinese forces that had made their way to India.

When the retreat from Burma ended in May 1942, Burma Corps was wound up. Operations had entered Eastern Army's area. Eastern Army was primarily an administrative rather than field command, and had perhaps too many responsibilities in addition to control of operations. Eastern Army commanded IV Corps in Assam and XV Corps in the Arakan. Both corps also had extensive rear area and internal security commitments, distracting them from the immediate front. An organisation known as V Force provided a screen of locally-raised guerillas and levies in front of the defensive positions.

On June 20, 1943 Wavell became Viceroy of India and was succeeded as CinC India by General Sir Claude Auchinleck. In August 1943, the Allies formed a new South East Asia Command (SEAC) to take over strategic responsibilities for the theatre. The reorganisation of the theatre command took about two months. On October 4 1943 Winston Churchill appointed Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten Supreme Commander of this new command. The American General Joseph Stilwell was Deputy Supreme Commander, among his many other appointments. On November 15 Auchinleck formally handed over responsibility for the conduct of operations against the Japanese in the theatre to Mountbatten.

With the creation of SEAC, Eastern Army was split into two. Under GHQ India, Eastern Command took over responsibility for the rear areas of Bihar, Orissa and most of Bengal. The Fourteenth Army under Slim took over responsibility for operations against the Japanese.

SEAC's land forces HQ was 11th Army Group under General Sir George Giffard. It controlled Fourteenth Army and the Ceylon Army, but Stilwell refused to place the Northern Combat Area Command (NCAC) under Giffard, using a variety of pretexts. At a meeting to sort out the chain of command for the three fronts in Burma, he astonished everyone by saying "I am prepared to come under General Slim's operational control until I get to Kamaing". This compromise worked because Slim was able to handle Stilwell. It was essential that there was one operational commander for the three fronts, North, Central and Southern, so that the intended attacks in late 1944 could be coordinated to prevent the Japanese concentrating large numbers of reserves for a counter attack on any one front.

11th Army Group remained in existence until November 12 1944 when it was redesignated Allied Land Forces South East Asia (ALFSEA), still under SEAC. Lieutenant General Sir Oliver Leese succeeded Giffard in command. 11th Army Group was redesignated because it was felt that an inter-Allied command was better than the purely British headquarters that 11th Army Group was. The change was made just after Stilwell was recalled to the U.S.. Lieutenant General Daniel Sultan became commander of the U.S. Forces, India-Burma Theater (USFIBT) and commander of NCAC, and this change placed his command under ALFSEA.

Japanese command

Note that in Japanese terminology, an "Army" was equivalent to a British or American "Corps". An "Area Army" was equivalent to an Allied "Army".

The chief command for the Japanese in South East Asia was the Southern Expeditionary Army, under Field Marshal Hisaichi Terauchi. This HQ was equivalent to an Allied theatre command. Southern Expeditionary army was responsible for operations as far afield as New Guinea, the Philippines and Burma

The initial invasion of Burma was conducted by 15th Army, under Lieutenant-General Shojiro Iida.

In late 1943, a new HQ, "Burma Area Army" was created, under General Masakazu Kawabe. It absorbed 15th Army, now under Lieutenant-General Renya Mutaguchi and responsible for the Central front, and the newly created 28th Army under Lieutenant-General Shoso Sakurai which controlled the Southern front.

In April 1944, another Army, 33rd Army, was created under Lieutenant-General Masaki Honda, to control the Northern front.

After the failure of the Imphal offensive in late 1944, there were several changes in command. At Burma Area Army, Kawabe was replaced by the former Vice War Minister, Hyotaro Kimura. Kimura was a shrewd strategist, but perhaps more of a logistics expert than fighting soldier, so Lieutenant-General Shinichi Tanaka was made his Chief of Staff. (In Japanese formations, the Chief of Staff had a more prominent role in the day-to-day control of operations than in Allied formations).

At the same time, Mutaguchi was removed from command of 15th Army and replaced by Lieutenant-General Shihachi Katamura. Many divisional commanders and Staff Officers also were sacked, removed or transferred.

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. |

See also

- Aung San a Burmese revolutionary who sided with the Japanese.

- The Burmese National Army was originally organized by the Minami Kikan as the Burmese Independence Army in December of 1941, where it then served as an auxiliary of the Japanese Army.

- Indian National Army an Indian army, largely recruited from POWs, who fought with the Japanese.

- Second Sino-Japanese War

References

- Field Marshal William Slim Defeat Into Victory

Further reading

- Jon Latimer Burma: The Forgotten War

- Louis Allen Burma: The Longest War

- Ian Lyall Grant & Kazuo Tamayama Burma 1942: The Japanese Invasion

- Tim Carew The Longest Retreat

- Donovan Webster The Burma Road : The Epic Story of the China-Burma-India Theater in World War II

- Brigadier Sir John Smyth Before the Dawn

- Mike Calvert Fighting Mad

- Lieutenant General Shojiro Ida From the Battlefields

- Ikuhiko Hata Road to the Pacific War

- Hideo Fujino Singapore and Burma

- Harumi Ochi Struggle in Burma

- Sadayoshi Shigematsu Fighting Around Burma

- Saiichi Sugita Burma Operations

- Michael Hickey The Unforgettable Army

- J.L. Hodsun War in the Sun

- E. Bruce Reynolds Thailand and Japan's Southern Advance

- Edward M. Young Aerial Nationalism: A History of Aviation in Thailand

- Don Moser and editors of Time-Life Books World War II: China-Burma-India',1978, Library of Congress no 77-93742

- Charles J. Rolo Wingate's Raiders

- Terence Dillon Rangoon to Kohima

- Sir Robert Thompson Make for the Hills has content related to the 1944 Chindit campaign

- Christopher Bayly & Tim Harper Forgotten Armies

External links

- Burma Star Association

- national-army-museum.ac.uk History of the British Army: Far East, 1941-45

- Imperial War Museum LondonBurma Summary

- Royal Engineers Museum Engineers in the Burma Campaigns

- Royal Engineers Museum Engineers with the Chindits

- Canadian War Museum: Newspaper Articles on the Burma Campaigns, 1941-1945

- US Center of Military History (USCMH): Burma 1942

- USCMH Centeral Burma 29 January - 15 July 1945

- USCMH India-Burma 2 April 1942-28 January 1945

- BBC Article on the Burma Campaign

- World War II animated campaign maps

- List of Regimental Battle Honours in the Burma Campaign (1942 - 1945) - Also some useful links

- Operations in Eastern Theatre, Based on India(pdf) from March 1942 to December 31 1942 despatch by Field Marshal The Viscount Wavell London Gazette

- Operations in the Indo-Burma Theatre Based on India from 21 June 1943 to 15 November 1943 (pdf) despatch by Field Marshal Sir Claude E. Auchinleck, War Office, The London Gazette 27 April 1948

- Operations in Burma(pdf) from 12 November 1944 to 15 August 1945 despatch by Lieutenant General Sir Oliver Leese London Gazette

- Sino-Japanese Air War 1937-45, see 1941 and 1942

- Burma Campaign, Orbat for 1942 campaign, Japan, Commonwealth, Chinese, USA

- A Forgotten Invasion: Thailand in Shan State, 1941-45

- Thailand's Northern Campaign in the Shan States 1942-45

Footnotes

- ^ World War II: China-Burma-India, Bibliography, page 157

- ^ Defeat Into Victory References pages 461,642

- ^ combined operation: No 5 commando