Mark Twain

Editing of this article by new or unregistered users is currently disabled. See the protection policy and protection log for more details. If you cannot edit this article and you wish to make a change, you can submit an edit request, discuss changes on the talk page, request unprotection, log in, or create an account. |

Samuel Langhorne Clemens | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | November 30, 1835 |

| Died | April 21, 1910 (aged 74) Redding, Connecticut |

| Pen name | Mark Twain |

| Occupation | Humorist, Novelist, Writer |

| Nationality | American |

| Genre | Historical fiction, non-fiction, satire, essay |

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30 1835 — April 21 1910),[1] better known by the pen name Mark Twain, was an American humorist, satirist, writer, and lecturer. Twain is most noted for his novels Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, which has since been called a Great American Novel,[2] and The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. He is also known for his quotations.[3][4] During his lifetime, Clemens became a friend to presidents, artists, leading industrialists, and European royalty.

Clemens enjoyed immense public popularity, and his keen wit and incisive satire earned him praise from both critics and peers. American author William Faulkner called Twain "the father of American literature."[5]

Biography

Youth

Samuel Clemens was born in Florida, Missouri, on November 30, 1835 to Tennessee country merchant, John Marshall Clemens (August 11, 1798–March 24, 1847) and Jane Lampton Clemens (June 18, 1803–October 27, 1890).[6]

He was the sixth of seven children. Only two of his siblings survived childhood, his brother Orion (July 17, 1825–December 11, 1897 and sister Pamela (September 19, 1827–August 31, 1904). His sister Margaret (May 31, 1830–August 17, 1839) died when he was four years old, and his brother Benjamin (June 8, 1832–May 12, 1842) died three years later. Another brother, Pleasant (1828–1829), only lived three months before Samuel was born. In addition to his older siblings, Samuel had one younger brother, Henry (July 13, 1838–June 21, 1858).[7] When Samuel was four, his family moved to Hannibal,[8] a port town on the Mississippi River that would serve as the inspiration for the fictional town of St. Petersburg in The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.[9] At that time, Missouri was a slave state in the union, and young Samuel became familiar with the institution of slavery, a theme he later explored in his writing.

Samuel Clemens was color blind, a condition that fueled his witty banter in the social circles of the day.[citation needed] In March 1847, when Samuel was 11, his father died of pneumonia.[citation needed] The following year, he became a printer's apprentice. In 1851, he began working as a typesetter and contributor of articles and humorous sketches for the Hannibal Journal, a newspaper owned by his brother, Orion. When he was 18, he left Hannibal and worked as a printer in New York, Philadelphia, St. Louis, and Cincinnati. At 22, Clemens returned to Missouri. On a voyage to New Orleans down the Mississippi, the steamboat pilot, "Bixby", inspired Clemens to pursue a career as a steamboat pilot, the third highest paying profession in America at the time, earning $250 per month ($155,000 today).[citation needed]

Because the steamboats at the time were constructed of very dry flammable wood, no lamps were allowed, making night travel a precarious endeavor. A steamboat pilot needed a vast knowledge of the ever-changing river to be able to stop at any of the hundreds of ports and wood-lots along the river banks. Clemens meticulously studied 2,000 miles (3,200 km) of the Mississippi for more than two years before he received his steamboat pilot license in 1859. While training for his pilot's license, Samuel convinced his younger brother Henry to work with him on the Mississippi. Henry was killed on June 21, 1858, when the steamboat he was working on exploded. Samuel was guilt-stricken over his brother's death and held himself responsible for the rest of his life. However, he continued to work on the river and served as a river pilot until the American Civil War broke out in 1861 and traffic along the Mississippi was curtailed.

Travels and family

Missouri was a slave state and considered by many to be part of the South, but it did not join the Confederacy. When the war began, Clemens and his friends formed a Confederate militia (depicted in an 1885 short story, "The Private History of a Campaign That Failed") and joined a battle where a man was killed. Clemens found he could not bear to kill a man and deserted. His friends joined the Confederate Army; Clemens joined his brother, Orion, who had been appointed secretary to the territorial governor of Nevada, and headed west.

Clemens and his brother traveled for more than two weeks on a stagecoach across the Great Plains and the Rocky Mountains. They visited the Mormon community in Salt Lake City. These experiences became the basis of the book Roughing It, and provided material for The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County. Clemens' journey ended in the silver-mining town of Virginia City, Nevada, where he became a miner.

After failing as a miner, Clemens worked at a Virginia City newspaper, the Territorial Enterprise. On February 3, 1863, he signed a humorous travel account "LETTER FROM CARSON - re: Joe Goodman; party at Gov. Johnson's; music" with "Mark Twain".[10]

Clemens then traveled to San Francisco, California, where he continued as a journalist and began lecturing. He met other writers such as Bret Harte, Artemus Ward and Dan DeQuille. An assignment in Hawaii became the basis for his first lectures. In 1867, a local newspaper funded a steamboat trip to the Mediterranean region.

During his tour of Europe and the Middle East, he wrote a popular collection of travel letters which were compiled as The Innocents Abroad in 1869. He also met Charles Langdon and saw a picture of Langdon's sister Olivia. Clemens claimed to have fallen in love at first sight. They met in 1868, were engaged a year later, and married in February 1870 in Elmira, New York. Olivia gave birth to a son, Langdon, who died of diphtheria after 19 months.

In 1871, Clemens moved his family to Hartford, Connecticut. There Olivia gave birth to three daughters: Susy, Clara, and Jean. Clemens also became good friends with fellow author William Dean Howells.

Clemens made a second tour of Europe, described in the 1880 book, A Tramp Abroad. He returned to America in 1900, having paid off his debts to his old firm. The Clemens' marriage lasted 34 years until Olivia's death in 1904.

In 1906, Clemens began his autobiography in the North American Review. Oxford University issued him a Doctorate of Literature a year later.

Clemens outlived Jean and Susy. He passed through a period of deep depression, which began in 1896 when his favorite daughter Susy died of meningitis. Olivia's death in 1904 and Jean's death on December 24, 1909, deepened his gloom.[11]

Life-long recurring "real" dream

Throughout his life, Clemens occasionally had recurring, emotional and profoundly touching dreams which he wrote were real. He recounted these dreams in the short story My Platonic Sweetheart. The dreams were about a young woman in the dream plane of existence, whom he loved and who loved him in return. In all the dreams, regardless of Clemens' waking age, they both appeared to be about 15 years old. The dreams appeared to have a timeless continuity, that is, even though several waking years might have passed between meetings, in the dream world there seemed to have passed little time. Their physical appearance was different each time, the names they called each other were different, and in a couple of the dreams she died, but none of this seemed to be an impediment to their continuing loving relationship each time they met.

Life as a writer

Mark Twain’s first important work, The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County, was first published in the New York Saturday Press on November 18, 1865. The only reason it was published there was because his story arrived too late to be included in a book Artemus Ward was compiling featuring sketches of the wild American West.

After this small burst of popularity, Twain was commissioned by the Sacramento Union to write letters about his travel experiences for publication in the newspaper, his first of which was to accompany the steamer Ajax in its maiden voyage to Hawaii, referred to at the time as the Sandwich Islands. These humorous letters proved the genesis to his work with the San Francisco Alta California newspaper, which designated him a traveling correspondent for a trip from San Francisco to New York City via the Panama isthmus. All the while Twain was writing letters meant for publishing back and forth, chronicling his experiences with his burlesque humor. On June 8, 1867, Twain set sail on the pleasure cruiser Quaker City for five months. This trip resulted in The Innocents Abroad or The New Pilgrims' Progress .

This book is a record of a pleasure trip. If it were a record of a solemn scientific expedition it would have about it the gravity, that profundity, and that impressive incomprehensibility which are so proper to works of that kind, and withal so attractive. Yet not withstanding it is only a record of a picnic, it has a purpose, which is, to suggest to the reader how he would be likely to see Europe and the East if he looked at them with his own eyes instead of the eyes of those who traveled in those countries before him. I make small pretense of showing anyone how he ought to look at objects of interest beyond the sea – other books do that, and therefore, even if I were competent to do it, there is no need.

In 1872, Twain published a second piece of travel literature, Roughing It, as a semi-sequel to Innocents. Roughing It is a semi-autobiographical account of Twain's journey to Nevada and his subsequent life in the American West. The book lampoons American and Western society in the same way that Innocents critiqued the various countries of Europe and the Middle East. Twain's next work would kept Roughing It's focus on American society but focused more on the events of the day. Entitled The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today, it was not a travel piece, as his previous two books had been, and it was his first attempt at writing a novel. The book is also notable because it is Twain's only collaboration; it was written with his neighbor Charles Dudley Warner.

Clemens' next two works drew on his experiences on the Mississippi River. Old Times on the Mississippi, a series of sketches published in the Atlantic Monthly in 1875, featured Twain’s disillusionment with Romanticism. Old Times eventually became the starting point for Life on the Mississippi. Clemens' next major publication was The Adventures of Tom Sawyer which drew on his youth in Hannibal. The character of Tom Sawyer was modeled on Samuel as a child. The book also introduced Huckleberry Finn as a supporting character.

The Prince and the Pauper, despite a storyline that is omnipresent in film and literature today, was not as well received. Pauper was Twain’s first attempt at fiction, and blame for its shortcomings are usually put on Twain having not been experienced enough in English society and the fact that it was produced after such a massive hit. In between the writing of Pauper, Twain had started Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (which he consistently had problems completing[citation needed]) and started and completed another travel book, A Tramp Abroad. A Tramp Abroad follows Twain as he travels through central and southern Europe.

Twain’s next major published work, Huckleberry Finn, solidified him as a great American writer after the production of what some call the elusive great American novel. Finn was an offshoot from Tom Sawyer and proved to have a more serious tone than its predecessor. The main premise behind Huckleberry Finn is the young boy’s belief in the right thing to do even though the majority of society believes that it was wrong. The book has become required reading in many schools throughout the United States because Huck ignores the rules and mores of the age to follow what he thinks is just (the story takes place in the 1850s where slavery is present). Four hundred manuscript pages of Huckleberry Finn were written in the summer of 1876, right after the publication of Tom Sawyer. Some accounts have Twain taking seven years off after his first burst of creativity, eventually finishing the book in 1883. Other accounts have Twain working on Finn in tandem with The Prince and the Pauper and other works in 1880 and other years. The last fifth of Finn is subject to much controversy. Some say that Twain experiences—as critic Leo Marx puts it—a "failure of nerve." Ernest Hemingway once said of Huckleberry Finn: “If you read it, you must stop where the Nigger Jim is stolen from the boys. That is the real end. The rest is just cheating.”

Near the end of Huckleberry Finn, Twain had written Life on the Mississippi, which is said to have heavily influenced the former book. The work recounts Twain’s memories and new experiences after a 22 year absence from the Mississippi. The book is of note because Twain introduces the real meaning of his pseudonym.

After his great work, Twain began turning to his business endeavors to keep them afloat and to stave off the increasing difficulties he had been having from his writing projects. Twain focused on the writing of President Ulysses S. Grant's Memoirs for his fledgling publishing company, finding time in between to write The Private History of a Campaign That Failed for The Century Magazine.

Twain next focused on A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, which featured him making his first big pronouncement of disappointment with politics. The tone become cynical to the point of almost being a rant against the established political system of the day (which would have been in King Arthur’s time), and eventually devolved into madness for the main character. The book was started in December 1885, then shelved a few months later until the summer of 1887, and eventually finished in the spring of 1889.

Some say that this work marked the beginning of the end for Twain as he fell into financial trouble and eschewed his humor vein. Twain had begun to furiously write articles and commentary with diminishing returns to pay the bills and keep his business intentions afloat, but it was not enough because he filed for bankruptcy in 1894. His next large scale work, The Tragedy of Pudd'nhead Wilson (aka Those Extraordinary Twins), brought about Twain’s sense of irony, though it has been misconstrued. There were parallels between this work and Twain’s financial failings, notably his desire to escape his current constraints and become a different person.

Twain’s next venture was straight fiction called Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc and dedicated it to his wife. Twain had long said that this was the work he was most proud of despite the criticism he received for it. The book had been a dream of Twain’s for a very long time, and he eventually thought it to be the work to save his publishing company. His financial adviser, Henry Huttleston Rogers, squashed that idea and got Twain out of that business all together, but the book was published nonetheless.

Twain’s wife died in 1904, and after the appropriate time Twain was allowed to publish some works that his wife, a de facto editor and censor throughout his life, had looked down upon. Of these works, The Mysterious Stranger, which pits the presence of Satan, aka “No. 44,” in various situations where the moral sense of human kind. This particular work was not published in Twain’s life, so there were three versions found in his manuscripts made between 1897 and 1905: the Hannibal version, the Eseldorf version, and the Print Shop version. Confusion between the versions led to an extensive publication of a jumbled version, and only recently have the original versions as Twain wrote them become available.

Twain’s last work was his autobiography, which he dictated and thought would be most entertaining if he went off on whims and tangents in non-sequential order. Some archivists and compilers had a problem with this and rearranged the biography into a more conventional form, thereby eliminating some of Twain’s humor and the flow of the book.

Financial matters

Clemens made a substantial amount of money through his writing, but he spent much of it in bad investments, mostly in new inventions. These included a bed clamp for infants, a new type of steam engine, the kaolatype (or collotype: a machine designed to engrave printing plates), and the Paige typesetting machine: a beautifully engineered mechanical marvel that amazed viewers when it worked, but was prone to breakdowns. Before it could be commercially perfected it was made obsolete by the Linotype. Finally, there was his publishing house, which enjoyed initial success selling the memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant but went bust soon after, losing money on an ill-advised idea that the general public would be interested in a Life of the Pope.

Clemens' writings and lectures combined with the help of a new friend enabled him to recover financially.[12] In 1893, he began a 15-year-long friendship with financier Henry Huttleston Rogers, a principal of Standard Oil. Rogers first made Clemens file for bankruptcy. Then Rogers had Clemens transfer copyrights to his written works to his wife, Olivia, to prevent creditors from gaining possession of them. Finally Rogers took absolute charge of Twain's money until all the creditors were paid. Twain then embarked on an around-the-world lecture tour to pay off his creditors in full, despite the fact that he was no longer under any legal obligation to do so.[13]

A late life friendship: Henry H. Rogers

While Twain openly credited Henry Rogers with saving him from financial ruin, their close friendship in their later years was mutually beneficial. As he lost 3 out of 4 of his children, and his beloved wife, Olivia Langdon, before his death in 1910, the Rogers family increasingly became Twain's own surrogate family. He became a frequent guest at the Rogers' townhouse in New York City, their 48-room summer home in Fairhaven, Massachusetts, and aboard the Rogers steam yacht, the Kanawha.

Twain was an admirer of the remarkable deaf and blind girl, Helen Keller. He first met her and Anne Sullivan at a party in the home of Laurence Hutton in New York City in the winter of 1894. Twain introduced them to Rogers, who with his wife, paid for a college education for Keller at Radcliffe College. It was Twain who is credited with labeling Sullivan, Helen's teacher, a "miracle worker." His choice of words later became inspiration for the title of William Gibson's play and film adaptation, The Miracle Worker.

Twain also introduced Rogers to journalist Ida M. Tarbell, who had grown up in the western Pennsylvania oil regions where Rogers had begun his career during the American Civil War. Beginning in 1902, she conducted detailed interviews with the Standard Oil magnate. Rogers, wily and normally-guarded in matters related to business and finance, may have been under the impression her work was to be complimentary. He was apparently uncustomarily forthcoming. However, Tarbell's interviews with Rogers formed the basis her negative exposé of the nefarious business practices of industrialist John D. Rockefeller and the massive Standard Oil organization. Her work, which became known at the time as muckraking (and is now known as investigative journalism), first ran as a series of articles, presented in installments in McClure's Magazine, which were later published together as a book, The History of the Standard Oil Company in 1904. Tarbell's exposé fueled negative public sentiment against the company and was a contributing factor in the U.S. government's antitrust legal actions against the Standard Oil Trust which eventually led to the breakup of the petroleum conglomerate in 1911.

While the two famous old men were widely regarded as drinking and poker buddies, they also exchanged letters when apart, and this was often since each traveled a great deal. Unlike Rogers' personal files, which have never become public, these interesting and insightful letters back and forth were published verbatim in an entire book, Mark Twain's Correspondence with Henry Huttleston Rogers, 1893-1909. In the written exchanges between the two men, there are pleasant examples of Rogers' sense of fun as well as Twain's well-known sense of humor. This provides a rare insight into private side of "Hell Hound Rogers", who had a well-known public reputation as a fearsome and ruthless robber baron.

On cruises aboard the Kanawha, they were joined at frequent intervals by Booker T. Washington, the famed former slave who had become a leading educator. From all outward appearances, Washington was apparently just another friend. However, known but to a very few, in fact, through him, "Hell Hound Rogers" was a secret philanthropist, aiding in educational efforts for African-Americans by deploying a new concept which came to be known as anonymous donor matching funds to contribute very large amounts of money in support of several teacher's colleges (now Hampton University and Tuskegee University) and literally dozens of small schools in the South over the same 15 year period of the Twain-Rogers friendship. (Dr. Washington only revealed this situation in June 1909 just weeks after Rogers' death as he made a pre-planned tour along the Virginian Railway, traveling in Rogers' private rail car "Dixie").

In April 1907, Twain and Rogers cruised together to Virginia aboard the Kanawha to the opening of the Jamestown Exposition, held at a site at Sewell's Point in a rural section of Norfolk County, Virginia. Twain's public popularity was such that large numbers of citizens paid to ride touring boats out to where the Kanawha was anchored in Hampton Roads in hopes of getting a glimpse of him. As the gathering of boats around the yacht became a safety hazard, he finally obliged by coming on deck and waving to the crowds. Because of poor weather conditions, the steam yacht was delayed for several days from leaving the Hampton Roads area and venturing into the Atlantic Ocean. Rogers and some of the others in his party (without Twain) returned to New York by rail. Because of his dislike of traveling by rail, Twain elected to return aboard the Kanawha, despite the delay. However, the news media reporters lost track of Twain's whereabouts; when he failed to return to New York City as scheduled, the New York Times speculated that he might have been "lost at sea."

Upon arriving safely in New York and learning of this, the humorist wrote a satirical article about the episode, including, in part,

- "...I will make an exhaustive investigation of this report that I have been lost at sea. If there is any foundation for the report, I will at once apprise the anxious public."[1]

This bore similarities to an earlier event in 1897 when he made his famous (and usually misquoted) remark "The report of my death is an exaggeration" in an article, after a reporter was sent to investigate whether he had died (in fact it was his cousin who was seriously ill).

Later that year, Twain and Rogers' son, Henry Jr. (Harry), returned to the Jamestown Exposition aboard the Kanawha. The humorist helped host Robert Fulton Day on September 23, 1907, celebrating the centennial of Fulton's invention of the steamboat. Twain was filling in for ailing former U.S. President Grover Cleveland and introduced Rear Admiral Purnell Harrington. According to a report published in Norfolk's Virginian-Pilot newspaper, Twain was met with a full five minutes of cheering and standing ovation. Members of the audience waved their hats and umbrellas. Deeply touched, Twain said, "When you appeal to my head, I don't feel it; but when you appeal to my heart, I do feel it."

Two years later, the two old friends again returned to Norfolk, Virginia. On April 3, 1909, the business community of Norfolk held a lavish banquet to honor Henry Rogers and his newly completed Virginian Railway. Twain was the keynote speaker in one of his last public appearances. His speech was widely quoted in newspapers across the United States. On the same trip, while Rogers and associates went to inspect his new coal pier near the mouth of the Elizabeth River at Sewell's Point, Twain used the time to visit children in several local schools. However, Twain declined to accompany Rogers and the rest of his party the next day as they set out for a 450 mile (725 km) tour across southern Virginia and West Virginia along the route of the newly-completed bituminous coal conveying railroad. Twain chose instead to return to New York via steamboat. [2]

On the morning of May 20, 1909, Rogers awoke at his New York City townhouse and told his wife he was feeling extremely poorly. His physician was called immediately, but before he could arrive, within the hour, the 69-year old was dead of a stroke.

That same morning, Twain was already aboard a New Haven Railroad passenger train en route from Connecticut to visit his friend and the family. Arriving at Grand Central Station, he was met by his daughter with the terrible news. Stricken with grief, he uncustomarily avoided news reporters who had gathered, saying only "This is terrible...I cannot talk about it." Two days later, he served as an honorary pallbearer at the Rogers funeral in New York City. However, he declined to join the funeral party on the train ride for the interment at Fairhaven. He said "I cannot bear to travel with my friend and not converse."

In and out with Halley's Comet

In 1909, Twain is quoted as saying:[14]

I came in with Halley's Comet in 1835. It is coming again next year, and I expect to go out with it. It will be the greatest disappointment of my life if I don't go out with Halley's Comet. The Almighty has said, no doubt: 'Now here are these two unaccountable freaks; they came in together, they must go out together.'

Samuel Langhorne Clemens died of angina pectoris on April 21, 1910 in Redding, Connecticut. Upon hearing of Twain's death, President Taft said:[15]

Mark Twain gave pleasure—real intellectual enjoyment—to millions, and his works will continue to give such pleasure to millions yet to come... His humor was American, but he was nearly as much appreciated by Englishmen and people of other countries as by his own countrymen. He has made an enduring part of American literature.

Mark Twain is buried in his wife's family plot in Elmira, New York.

Legacy

Clemens' birthplace is preserved in Florida, Missouri .The Mark Twain Boyhood Home and Museum in Hannibal, Missouri is one of the most popular museums because it provides the setting for much of the author's work. The home of a childhood friend is preserved as the "Thatcher House" and is said to be the inspiration for his fictional character Becky Thatcher. Clemens was awarded an honorary doctorate from Oxford, and the robes he wore to that ceremony and on many other occasions afterward (including one daughter's wedding) are on display in the museum. Visitors to Hannibal can also tour the Mark Twain Cave and ride a riverboat on the Mississippi River.

In 1874, Clemens built a family home in Hartford, Connecticut, where he and his wife raised their three daughters. That home is preserved and open to visitors as the Mark Twain House. Clemens lived in many homes in the United States and abroad.

Twain's legacy lives on today as his namesakes continue to multiply. Several schools are named after him, including one in Houston (Twain Elementary School), which has a statue of Twain sitting on a bench. In 1998, The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts created the Mark Twain Prize for American Humor, awarded annually. The Mark Twain Award is an award given annually to a book for children in grades four through eight by the Missouri Association of School Librarians. Stetson University in DeLand, Florida, sponsors the Mark Twain Young Authors' Workshop each summer in collaboration with the Boyhood Home and Museum in Hannibal. The program[3] is open to young authors in grades five through eight. The museum sponsors the Mark Twain Creative Teaching Award.[4]

Actor Hal Holbrook created a one man show called "Mark Twain Tonight". In 1967, CBS broadcast a performance of "Mark Twain Tonight" for which Holbrook won an Emmy Award. Holbrook has been performing "Mark Twain Tonight" regularly for 50 years, include three runs on Broadway, 1966, 1977, and 2005, the first of which won him a Tony Award. Additionally, like countless influential individuals, Mark Twain was awarded the honor of having an asteroid named after him.

Pen names

Clemens used different pen names before deciding on Mark Twain. He signed humorous and imaginative sketches "Josh" until 1863. Additionally, he used the pen name "Thomas Jefferson Snodgrass" for a series of humorous letters.[16] He maintained that his primary pen name, "Mark Twain", came from his years working on Mississippi riverboats, where two fathoms (12 ft, approximately 3.7 m) or "safe water" was measured on the sounding line. The riverboatman's cry was "mark twain" or, more fully, "by the mark twain" ("twain" is an archaic term for two). "By the mark twain" meant "according to the mark [on the line], [the depth is] two fathoms"

Clemens claimed that his famous pen name was not entirely his invention. In Chapter 50 of Life on the Mississippi he wrote:[17]

Captain Isaiah Sellers was not of literary turn or capacity, but he used to jot down brief paragraphs of plain practical information about the river, and sign them "MARK TWAIN," and give them to the New Orleans Picayune. They related to the stage and condition of the river, and were accurate and valuable; ... At the time that the telegraph brought the news of his death, I was on the Pacific coast. I was a fresh new journalist, and needed a nom de guerre; so I confiscated the ancient mariner's discarded one, and have done my best to make it remain what it was in his hands—a sign and symbol and warrant that whatever is found in its company may be gambled on as being the petrified truth; how I have succeeded, it would not be modest in me to say.

Career overview

Twain began his career writing light, humorous verse but evolved into a grim, almost profane chronicler of the vanities, hypocrisies and murderous acts of mankind. At mid-career, with Huckleberry Finn, he combined rich humor, sturdy narrative and social criticism.

Twain was a master at rendering colloquial speech and helped to create and popularize a distinctive American literature built on American themes and language.

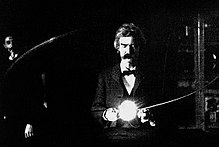

Twain was also fascinated with science and scientific inquiry. He developed a close and lasting friendship with Nikola Tesla, and the two spent much time together in Tesla's laboratory. Twain's book A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court features a time traveler from the America of Twain's day, using his knowledge of science to introduce modern technology to Arthurian England. Twain also patented an improvement in adjustable and detachable straps for garments.

Twain was opposed to vivisection of any kind, not on a scientific basis but rather an ethical one. He stated that no sentient being should be made to suffer for another without consent.[18]

I am not interested to know whether vivisection produces results that are profitable to the human race or doesn't. ... The pain which it inflicts upon unconsenting animals is the basis of my enmity toward it, and it is to me sufficient justification of the enmity without looking further.

From 1901 until his death in 1910, Twain was vice president of the American Anti-Imperialist League.[19] The league opposed the annexation of the Philippines by the United States. Twain wrote Incident in the Philippines, posthumously published in 1924, in response to the Moro Crater Massacre, in which six hundred Moros were killed. Many but not all of Mark Twain's neglected and previously uncollected writings on anti-imperialism appeared for the first time in book form in 1992.

From the time of its publication there have been occasional attempts to ban Huckleberry Finn from various libraries because Twain's use of local color is offensive to some people. Although Twain was against racism and imperialism far ahead of the public sentiment of his time, those who have only superficial familiarity with his work have sometimes condemned it as racist because it accurately depicts language in common use in the 19th-century United States. Expressions that were used casually and unselfconsciously then are often perceived today as racist; today, such racial epithets are far more visible and condemned. Twain himself would probably be amused by these attempts; in 1885, when a library in Concord, Massachusetts banned the book, he wrote to his publisher, "They have expelled Huck from their library as 'trash suitable only for the slums'; that will sell 25,000 copies for us for sure."

Many of Mark Twain's works have been suppressed at times for various reasons. When an anonymous slim volume was published in 1880 entitled 1601: Conversation, as it was by the Social Fireside, in the Time of the Tudors., Twain was among those rumored to be the author. The issue was not settled until 1906, when Twain acknowledged his literary paternity of this scatological masterpiece.

At least Twain saw 1601 published during his lifetime. During the Philippine-American War, Twain wrote an anti-war article entitled The War Prayer. Through this internal struggle, Twain expresses his opinions of the absurdity of slavery and the importance of following one's personal conscience before the laws of society. It was submitted to Harper's Bazaar for publication, but on March 22, 1905, the magazine rejected the story as "not quite suited to a woman's magazine." Eight days later, Twain wrote to his friend Dan Beard, to whom he had read the story, "I don't think the prayer will be published in my time. None but the dead are permitted to tell the truth." Because he had an exclusive contract with Harper & Brothers, Mark Twain could not publish The War Prayer elsewhere; it remained unpublished until 1923.

In later years, Twain's family suppressed some of his work which was especially irreverent toward conventional religion, notably Letters from the Earth, which was not published until 1962. The anti-religious The Mysterious Stranger was published in 1916, although there is some scholarly debate as to whether Twain actually wrote the most familiar version of this story. Twain was critical of organized religion and certain elements of the Christian religion through most of the end of his life, though he never renounced Presbyterianism[20]

Bibliography

- (1867) Advice for Little Girls (fiction)

- (1867) The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County (fiction)

- (1868) General Washington's Negro Body-Servant (fiction)

- (1868) My Late Senatorial Secretaryship (fiction)

- (1869) The Innocents Abroad (non-fiction travel)

- (1870-71) Memoranda (monthly column for The Galaxy magazine)

- (1871) Mark Twain's (Burlesque) Autobiography and First Romance (fiction)

- (1872) Roughing It (non-fiction)

- (1873) The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today (fiction, made into a play)

- (1875) Sketches New and Old (fictional stories)

- (1876) Old Times on the Mississippi (non-fiction)

- (1876) The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (fiction)

- (1876) A Murder, a Mystery, and a Marriage (fiction); (1945, private edition), (2001, Atlantic Monthly).[21]

- (1877) A True Story and the Recent Carnival of Crime (stories)

- (1877) The Invalid's Story (Fiction)

- (1878) Punch, Brothers, Punch! and other Sketches (fictional stories)

- (1880) A Tramp Abroad (travel)

- (1880) 1601: Conversation, as it was by the Social Fireside, in the Time of the Tudors (fiction)

- (1882) The Prince and the Pauper (fiction)

- (1883) Life on the Mississippi (non-fiction)

- (1884) Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (fiction)

- (1889) A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court (fiction)

- (1892) The American Claimant (fiction)

- (1892) Merry Tales (fictional stories)

- (1893) The £1,000,000 Bank Note and Other New Stories (fictional stories)

- (1894) Tom Sawyer Abroad (fiction)

- (1894) The Tragedy of Pudd'nhead Wilson (fiction)

- (1896) Tom Sawyer, Detective (fiction)

- (1896) Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc (fiction)

- (1897) How to Tell a Story and other Essays (non-fictional essays)

- (1897) Following the Equator (non-fiction travel)

- (1900) The Man That Corrupted Hadleyburg (fiction)

- (1900) A Salutation Speech From the Nineteenth Century to the Twentieth (essay)

- (1901) The Battle Hymn of the Republic, Updated (satire)

- (1901) Edmund Burke on Croker and Tammany (political satire)

- (1901) To the Person Sitting in Darkness (essay)

- (1902) A Double Barrelled Detective Story (fiction)

- (1904) A Dog's Tale (fiction)

- (1904) Extracts from Adam's Diary (fiction)

- (1905) King Leopold's Soliloquy (political satire)

- (1905) The War Prayer (fiction)

- (1906) The $30,000 Bequest and Other Stories (fiction)

- (1906) What Is Man? (essay)

- (1906) Eve's Diary (fiction)

- (1907) Christian Science (non-fiction critique)

- (1907) A Horse's Tale (fiction)

- (1907) Is Shakespeare Dead? (non-fiction)

- (1909) Captain Stormfield's Visit to Heaven (fiction)

- (1909) Letters from the Earth (fiction, published posthumously)

- (1910) Queen Victoria's Jubilee (non-fiction)

- (1912) My Platonic Sweetheart (dream journal, possibly non-fiction)

- (1916) The Mysterious Stranger (fiction, possibly not by Twain, published posthumously)

- (1924) Mark Twain's Autobiography (non-fiction, published posthumously)

- (1935) Mark Twain's Notebook (published posthumously)

- (1969) No. 44, The Mysterious Stranger (fiction, published posthumously)

- (1985) Concerning the Jews (published posthumously)

- (1992) Mark Twain's Weapons of Satire: Anti-Imperialist Writings on the Philippine-American War. Jim Zwick, ed. (Syracuse University Press) ISBN 0-8156-0268-5 (previously uncollected, published posthumously)

- (1995) The Bible According to Mark Twain: Writings on Heaven, Eden, and the Flood (published posthumously)

See also

- Bernard DeVoto

- List of American poets

- Local color

- Mark Twain Award

- Mark Twain House

- Mark Twain in popular culture

- Mark Twain Memorial Bridge

- Mark Twain Prize for American Humor

- Mark Twain Boyhood Home & Museum

- Mark Twain I.S. 239

Notes

- ^ "The Mark Twain House Biography". Retrieved 2006-10-24.

- ^ "Mark Twain's Huckleberry Finn". Retrieved 2007-04-09.

- ^ "Mark Twain quotations". Retrieved 2006-10-24.

- ^ "Mark Twain Quotes - The Quotations Page". Retrieved 2006-10-24.

- ^ Jelliffe, Robert A. (1956). Faulkner at Nagano. Tokyo: Kenkyusha, Ltd.

- ^ Kaplan, Fred (2007). "Chapter 1: The Best Boy You Had 1835-1847". The Singular Mark Twain. Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-47715-5.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help). Cited in ""Excerpt: The Singular Mark Twain". About.com: Literature: Classic. Retrieved 2006-10-11. - ^ "Mark Twain's Family Tree" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-01-01.

- ^ "Mark Twain, American Author and Humorist". Retrieved 2006-10-25.

- ^ Lindborg, Henry J. "Adventures of Huckleberry Finn". Retrieved 2006-11-11.

- ^ "Mark Twain quotations".

- ^ "The Mark Twain House". Retrieved 2006-11-17.

- ^ Lauber, John. The Inventions of Mark Twain: a Biography. New York: Hill and Wang, 1990.

- ^ Cox, James M. Mark Twain: The Fate of Humor. Princeton University Press, 1966.

- ^ Albert Bigelow Paine. "Mark Twain, a Biography". Retrieved 2006-11-01.

- ^ Esther Lombardi, about.com. "Mark Twain (Samuel Langhorne Clemens)". Retrieved 2006-11-01.

- ^ Thomas Jefferson Snodgrass, (Charles Honce, James Bennet, ed.), Pascal Covici, Chicago, 1928

- ^ Life on the Mississippi, chapter 50

- ^ "Mark Twain Quotations - Vivisection". Retrieved 2006-10-24.

- ^ Mark Twain's Weapons of Satire: Anti-Imperialist Writings on the Philippine-American War. (1992, Jim Zwick, ed.) ISBN 0-8156-0268-5

- ^ The Religious Affiliation Mark Twain celebrated American author

- ^ Barber, Greg (2001-06-25). "A Mysterious Manuscript" (HTML). Mark Twain: Media Watch Special Report. PBS Online News Hour. Retrieved 2006-10-09.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)

References

- Ken Burns, Dayton Duncan, and Geoffrey C. Ward, Mark Twain: An Illustrated Biography. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2001 (ISBN 0-3754-0561-5)

- Gregg Camfield. The Oxford Companion to Mark Twain. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002 (ISBN 0-1951-0710-1)

- James M. Cox. Mark Twain: The Fate of Humor. Princeton University Press, 1966 (ISBN 0-8262-1428-2)

- Everett Emerson. Mark Twain: A Literary Life. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2000 (ISBN 0-8122-3516-9)

- Shelley Fisher Fishkin, ed. A Historical Guide to Mark Twain. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002 (ISBN 0-1951-3293-9)

- Jason Gary Horn. Mark Twain: A Descriptive Guide to Biographical Sources. Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press, 1999 (ISBN 0-8108-3630-0)

- William Dean Howells. My Mark Twain. Mineloa, New York: Dover Publications, 1997 (ISBN 0-486-29640-7)

- Fred Kaplan. The Singular Mark Twain: A Biography. New York: Doubleday, 2003 (ISBN 0-3854-7715-5)

- Justin Kaplan. Mr. Clemens and Mark Twain: A Biography. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1966 (ISBN 0-6717-4807-6)

- J. R. LeMaster and James D. Wilson, eds. The Mark Twain Encyclopedia. New York: Garland, 1993 (ISBN 0-8240-7212-X)

- Patrick K. Ober . Mark Twain and Medicine: "Any Mummery Will Cure". Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2003 (ISBN 0-8262-1502-5)

- Albert Bigelow Paine. Mark Twain, A Biography: The Personal and Literary Life of Samuel Langhorne Clemens. New York: Harper & Bros., 1912. (ISBN 1-8470-2983-3)

- Ron Powers. Dangerous Water: A Biography of the Boy Who Became Mark Twain. New York: Da Capo Press, 1999. (ISBN 0-3068-1086-7)

- Ron Powers. Mark Twain: A Life. New York: Random House, 2005. (0-7432-4899-6)

- R. Kent Rasmussen. Critical Companion to Mark Twain: A Literary Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 2007. (Revised edition of Mark Twain A to Z) (ISBN 0-8160-6225-0)

- R. Kent Rasmussen, ed. The Quotable Mark Twain: His Essential Aphorisms, Witticisms and Concise Opinions. Chicago: Contemporary Books, 1997 (ISBN 0-8092-2987-0)

External links

Works

- Works by Mark Twain at Project Gutenberg. More than 60 texts are freely available.

- Mark Twain Quotes, Newspaper Collections and Related Resources

- Twain on The Awful German Language

- Audio book recording with accompanying text of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

- Many Twain stories are read in Mister Ron's Basement (Number 431 -- Celebrated Jumping Frog, Numbers 195-199, Number 146 -- Million Pound Banknote, Nos. 67-71, and Number 6 -- The War Prayer) Podcast

- Mark Twain on Scientific Research / Pains of Lowly Life (1900)

- Mark Twain Quotes

- Quotes mistakenly attributed to Mark Twain

Studying

- The Mark Twain Papers and Project of the Bancroft Library, University of California Berkeley. Home to the largest archive of Mark Twain's papers and the editors of a critical edition of all of Mark Twain's writings.

- Mark Twain Room (Houses original manuscript of Huckleberry Finn)

- The University of California Press Publishers of the critical edition of Mark Twain's writings.

- Elmira College Center for Mark Twain Studies

- Ever the Twain Shall Meet, a guide to Mark Twain on the Web

- The Fountain Pens used by Mark Twain

- "The Mark Twain they didn’t teach us about in school", by Helen Scott, from International Socialist Review 10, Winter 2000, pp.61-65.

- The Mark Twain Museum's education section has lesson plans for teachers as well as homework help for students

- University students discuss Mark Twain's essay Luck

Life

- Full text of My Platonic Sweetheart , a dream journal by Mark Twain

- Full text of the biography Mark Twain by Archibald Henderson

- The Mark Twain House in Hartford, CT

- The Mark Twain Boyhood Home in Hannibal, MO

- The Hannibal Courier Post A Look at the Life and Works of Mark Twain

- Mark Twain: Known To Everyone—Liked By All, a Ken Burns film shown on PBS.

- Literary Pilgrimages—Mark Twain sites

Other

- "Origins of the name Mark Twain", from Encyclopaedia Britannica latest edition, full article.

- Mark Twain

- American humorists

- American memoirists

- American novelists

- American satirists

- American short story writers

- American travel writers

- Alternate history writers

- American humanists

- People of the Philippine-American War

- Missouri writers

- People from Elmira, New York

- People from Hannibal, Missouri

- People from St. Louis

- Quincy-Hannibal Area

- Scottish-Americans

- People known by pseudonyms

- 1835 births

- 1910 deaths

- Authors whose works are in the public domain