Bat

| Bats Temporal range: Late Paleocene - Recent

| |

|---|---|

| |

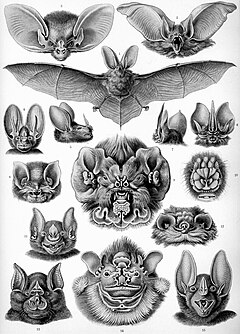

| "Chiroptera" from Ernst Haeckel's Kunstformen der Natur, 1904 | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Infraclass: | |

| Superorder: | |

| Order: | Chiroptera Blumenbach, 1779

|

| Suborders | |

|

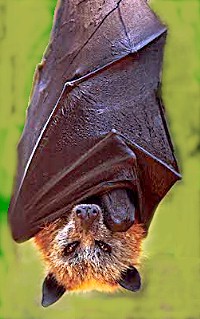

Megachiroptera | |

A bat is a mammal in the order Chiroptera. Their most distinguishing feature is that their forelimbs are developed as wings, making them the only mammals in the world naturally capable of flight (other mammals, such as flying squirrels and gliding phalangers, can glide for limited distances but are not capable of true sustainable flight). The word Chiroptera can be translated from the Greek words for "hand wing," as the structure of the open wing is very similar to an outspread human hand with a membrane (patagium) between the fingers that also stretches between hand and body.

There are estimated to be about 1,100 species of bats worldwide, accounting for about 20% of all mammal species.[1] About 70% of bats are insectivores. Of the remainder, most feed on fruits and their juices; three species sustain themselves with blood and some prey on vertebrates. These bats include the leaf-nosed bats (Phyllostomidae) of Central America and South America, and the related bulldog bats (Noctilionidae) that feed on fish. At least two known species of bat feed on other bats: the Spectral Bat, also called the American False Vampire bat, and the Ghost Bat of Australia. One species, the Greater Noctule bat, is believed to catch and eat small birds in the air. Despite the cold weather, there are 6 species of bats in Alaska.

Some of the smaller bat species are important pollinators of some tropical flowers. Indeed, many tropical plants are now found to be totally dependent on them, not just for pollination, but for spreading their seeds by eating the resulting fruits. This role explains environmental concerns when a bat is introduced in a new setting. Tenerife provides a recent example with the introduction of the Egyptian fruit bat.

Classification and evolution

Bats are mammals. Though sometimes called "flying rodents", "flying mice," or even mistaken for insects and birds, bats are not, in fact, rodents. There are two suborders of bats:

- Megachiroptera (megabats)

- Microchiroptera (microbats/echolocating bats)

Despite the name, not all megabats are larger than microbats. The major distinction between the two suborders is based on other factors:

- Microbats use echolocation, whereas megabats do not (except for Rousettus and relatives, which do).

- Microbats lack the claw at the second toe of the forelimb.

- The ears of microbats do not form a closed ring, but the edges are separated from each other at the base of the ear.

- Microbats lack underfur; they have only guard hairs or are naked.

Megabats eat fruit, nectar or pollen while microbats eat insects, blood (small quantities of the blood of animals), small mammals, and fish, relying on echolocation for navigation and finding prey.

Genetic evidence indicates that megabats should be placed within the four major lines of microbats (Yinochiroptera), who originated during the early Eocene. The same research also seems to show that the microbats are the original bats while megabats evolved from them independently through parallel evolution, where most of them lost the ability to use echolocation.

There is some morphological evidence that Megachiroptera evolved flight separately from Microchiroptera; if so, the Microchiroptera would have uncertain affinities. When adaptations to flight are discounted in a cladistic analysis, the Megachiroptera are allied to primates by anatomical features that are not shared with Microchiroptera. But this alternative seems to have little support these days.

Little is known about the evolution of bats, since their small, delicate skeletons do not fossilize well. However a Late Cretaceous tooth from South America resembles that of an early Microchiropteran bat. The oldest known definite bat fossils, such as Icaronycteris, Archaeonycteris, Palaeochiropteryx and Hassianycteris, are from the early Eocene (about 50 million years ago), but they were already very similar to modern microbats. Archaeopteropus, formerly classified as the earliest known megachiropteran, is now classified as a microchiropteran.

Bats are traditionally grouped with the tree shrews (Scandentia), colugos (Dermoptera), and the primates in superorder Archonta because of the similarities between Megachiroptera and these mammals. However, molecular studies have placed them as sister group to Ferungulata -- a large grouping including carnivorans, pangolins, odd-toed ungulates, even-toed ungulates, and whales.

- ORDER CHIROPTERA (Ky-rop`ter-a) (Gr. cheir, hand, + pteron, wing)

- Suborder Megachiroptera (megabats)

- Suborder Microchiroptera (microbats)

- Superfamily Emballonuroidea

- Superfamily Molossoidea

- Superfamily Nataloidea

- Superfamily Noctilionoidea

- Mormoopidae (Ghost-faced or Moustached bats)

- Mystacinidae (New Zealand short-tailed bats)

- Noctilionidae (Bulldog bats or Fisherman bats)

- Phyllostomidae (Leaf-nosed bats) This family contains (among others) the Vampire bats

- Superfamily Rhinolophoidea

- Superfamily Rhinopomatoidea

- Superfamily Vespertilionoidea

Megabats are primarily fruit- or nectar-eating. They have probably evolved for some time in New Guinea without microbat concurrention. This has resulted in some smaller megabats of the genus Nyctimene becoming (partly) insectivorous to fill the vacant microbat ecological niche. Furthermore, there is some evidence that the fruit bat genus Pteralopex from the Solomon Islands, and its close relative Mirimiri from Fiji, have evolved to fill some niches that were open because there are no nonvolant mammals in those islands.

Anatomy

By emitting high-pitched sounds and listening to the echoes, microbats locate prey and other nearby objects. This is the process of echolocation, an ability they share with dolphins and whales. Two groups of moths exploit the bats' senses: tiger moths produce ultrasonic signals to warn the bats that the moths are chemically-protected (aposematism) (this was once thought to be a form of "radar jamming", but this theory has been disproved); the moths Noctuidae have a hearing organ called a tympanum which responds to an incoming bat signal by causing the moth's flight muscles to twitch erratically, sending the moth into random evasive manoeuvres.

Although the eyes of most microbat species are small and poorly developed, their sense of vision is typically very good, especially at long distances, beyond the range of echolocation. It has even been discovered that some species are able to detect ultraviolet light. Their senses of smell and hearing are excellent.

The teeth of microbats resemble those of the insectivorans. They are very sharp in order to bite through the hardened armour of insects or the skin of fruits.

While other mammals have one-way valves only in their veins to prevent the blood from flowing backwards, bats also have the same mechanism in their arteries.

The finger bones of bats are much more flexible than those of other mammals. One reason is that the cartilage in their fingers lacks calcium and other minerals nearer the tips, increasing their ability to bend without splintering. The cross-section of the finger bone is also flattened instead of circular as is the bone in a human finger, making it even more flexible. The skin on their wing membranes is a lot more elastic and can stretch much more than is usually seen among mammals.

Because their wings are much thinner than those of birds, bats can manoeuvre more quickly and more precisely than birds. The surface of their wings are also equipped with touch-sensitive receptors on small bumps called Merkel cells, found in most mammals, including humans. But these sensitive areas are different in bats as each bump has a tiny hair in the centre,[2] making it even more sensitive, and allowing the bat to detect and collect information about the air flowing over its wings. An additional kind of receptor cell is found in the wing membrane of species that use their wings to catch prey. This receptor cell is sensitive to the stretching of the membrane.[2] The cells are concentrated in areas of the membrane where insects hit the wings when the bats capture them.

One species of bat has the longest tongue of any mammal relative to its body size. This is extremely beneficial to them in terms of pollination and feeding - their long narrow tongues can reach deep down into the long cup shape of some flowers. When their tongue retracts, it coils up inside their rib cage.[3]

Reproduction

Mother bats usually have only one offspring per year. A baby bat is referred to as a pup. Pups are usually left in the roost when they are not nursing. However, a newborn bat can cling to the fur of the mother and be transported, although they soon grow too large for this. It would be difficult for an adult bat to carry more than one young, but normally only one young is born. Bats often form nursery roosts, with many females giving birth in the same area, be it a cave, a tree hole, or a cavity in a building. Mother bats are able to find their young in huge colonies of millions of other pups. Pups have even been seen to feed on other mothers' milk if their mother is dry. Only the mother cares for the young, and there is no continuous partnership with male bats.

The ability to fly is congenital, but after birth the wings are too small to fly. Young microbats become independent at the age of 6 to 8 weeks, megabats not until they are four months old. At the age of two years, bats are sexually mature.

A single bat can live over 20 years, but the bat population growth is limited by the slow birth rate.[4]

Behaviour

Most microbats are active at night or at twilight.

Many bats migrate, while others pass into torpor in cold weather but rouse themselves and feed when warm spells permit insect activity. Yet others retreat to caves for winter and hibernate for six months.

The social structure of bats varies, with some bats leading a solitary life and others living in caves colonized by more than a million bats. The fission-fusion social structure is seen among several species of bats. "Fusion" refers to the grouping of large numbers of bats in one roosting area and "fission" is the breaking apart and mixing of subgroups, with individual bats switching roosts with others and often ending up in different trees and with different roostmates.

Studies also show that bats make all kinds of sounds to communicate with others. Scientists in the field have listened to bats and have been able to identify some sounds with some behaviour bats will make right after the sounds are made.

As vectors for pathogens

Bats are natural reservoirs or vectors for a large number of zoonotic pathogens[5] including rabies,[6] SARS,[7] Henipavirus (ie. Nipah virus and Hendra virus)[8] and possibly ebola virus.[9] Their high mobility, broad distribution, social behaviour (communal roosting, fission-fusion social structure) and close evolutionary relationship to humans make bats favourable hosts and disseminators of disease. Many species also appear to have a high tolerance for harbouring pathogens and often do not develop disease while infected.

Only 0.5% of bats carry rabies. However, of the very few cases of rabies reported in the United States every year, most are caused by bat bites[citation needed]. Although most bats do not have rabies, those that do may be clumsy, disoriented, and unable to fly, which makes it more likely that they will come into contact with humans. Although one should not have an unreasonable fear of bats, one should avoid handling them or having them in one's living space, as with any wild animal. If a bat is found in living quarters near a child, mentally handicapped person, intoxicated person, sleeping person, or pet, the person or pet should receive immediate medical attention for rabies. Bats have very small teeth and can bite a sleeping person without necessarily being felt.

If a bat is found in a house and the possibility of exposure cannot be ruled out, the bat should be sequestered and an animal control officer called immediately, so that the bat can be analysed. This also applies if the bat is found dead. If it is certain that nobody has been exposed to the bat, it should be removed from the house. The best way to do this is to close all the doors and windows to the room except one to the outside. The bat should soon leave.

Due to the risk of rabies and also due to health problems related to their guano, bats should be excluded from inhabited parts of houses. For full detailed information on all aspects of bat management, including how to capture a bat, what to do in case of exposure, and how to bat-proof a house humanely, see the Centers for Disease Control's website on bats and rabies. In certain countries, such as the United Kingdom, it is illegal to handle bats without a license.

Where rabies is not endemic, as throughout most of Western Europe, small bats can be considered harmless. Larger bats can give a nasty bite. They should be treated with the respect due to any wild animal.

Cultural aspects

The bat is sacred in Tonga and West Africa and is often considered the physical manifestation of a separable soul. Bats are closely associated with vampires, who are said to be able to shapeshift into bats, fog, or wolves. Bats are also a symbol of ghosts, death, and disease. Among some Native Americans, such as the Creek, Cherokee and Apache, the bat is a trickster spirit. Chinese lore claims the bat is a symbol of longevity and happiness, and is similarly lucky in Poland and geographical Macedonia and among the Kwakiutl and Arabs.

In Western Culture, the bat is often a symbol of the night and its foreboding nature. The bat is a primary animal associated with fictional characters of the night such as both villains like Dracula and heroes like Batman. The association of the fear of the night with the animal was treated as a literary challenge by Kenneth Oppel, who created a best selling series of novels, beginning with Silverwing, which feature bats as the central heroic figures much in a similar manner as the classic novel Watership Down did for rabbits. An old wives' tale has it that bats will entangle themselves in people's hair. A likely root to this myth is that insect-eating bats seeking prey may dive erratically toward people, who attract mosquitoes and gnats, leading the squeamish to believe that the bats are trying to get in their hair.

In the United Kingdom all bats are protected under the Wildlife and Countryside Acts, and even disturbing a bat or its roost can be punished with a heavy fine.

Austin, Texas, under the Congress Avenue bridge, is the summer home to North America's largest urban bat colony, an estimated 1,500,000 Mexican free-tailed bats, who eat an estimated 10,000 to 30,000 pounds of insects each night and attract 100,000 tourists each year.

In Sarawak, Malaysia bats are protected species under the Wildlife Protection Ordinance 1998 (see Malaysian Wildlife Law). The large Naked bat (see Mammals of Borneo) and Greater Nectar bat are consumed by the local communities.

Bat houses

Just as many people put up bat houses to attract bats as birdhouses to attract birds. Reasons for this vary, but mostly center around the fact that bats are the primary nocturnal insectivores in most if not all ecologies. Bat houses can be made from scratch, made from kits, or bought ready made. Plans for bat houses exist on many web sites, as well as guidelines for designing a bat house. Some conservation societies are giving away free bat houses to bat enthusiasts worldwide.

A bat house constructed in 1991 at the University of Florida campus next to Lake Alice in Gainesville has a population of over 100,000 free-tailed bats.[10]

"Bats are Bugs" theories and controversey

In some cultural circles, it is believed that bats are in fact insects, as opposed to the commonly held belief that bats are mammals. [11]

Evidence for the bats are bugs theory is as follows:

- Flight

- Ugly

- Hairy

- Susie Derkins dislikes bats

See also

- European Bat Night

- Persian Trident Bat (Triaenops persicus)

- Bat bomb

- Batman

- Bat World Sanctuary

- Fictional bats

- Flying and gliding animals

- Mammal

- Audiograms in mammals

References

- ^ Tudge, Colin (2000). The Variety of Life. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-860426-2.

- ^ a b Melissa Calhoun (15 December 2005). "Bats Use Touch Receptors on Wings to Fly, Catch Prey, Study Finds". Retrieved 2006-10-18.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2006/12/061206-tongue-photo.html

- ^ http://www.batworld.org/main/main.html Retrieved 22 October 2006.

- ^ Wong, S, Lau, S, Woo, P, Yuen, KY. (2007). Bats as a continuing source of emerging infections in humans. Rev Med Virol. 17(2):67–91.

- ^ McColl, KA, Tordo, N, Aquilar Setien, AA. (2000). Bat lyssavirus infections. Rev Sci Tech. 19(1):177–196.

- ^ Li, W, Shi, A, Yu, M et al (2005) Bats are natural reservoirs of SARS-like coronaviruses. Science 310(5748):676–679.

- ^ Halpin K, Young PL, Filed HE, Mackenzie JS. Isolation of Hendra virus from pteropid bats: a natural reservoir of Hendra virus. Journal of General Virology 2000; 81:1927–1932. PMID 10900029. Available from http://vir.sgmjournals.org/cgi/content/full/81/8/1927

- ^ Leroy, EM, Kimulugui, B, Pourrut, X et al. (2005). Fruit bats as reservoirs of Ebola virus. Nature. 438:575–576.

- ^ BACKYARD BAT HOUSES PROMOTE PEST CONTROL, SAYS UF EXPERT. Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida. October 29, 2001. Last accessed January 9, 2007.

- ^ http://picayune.uclick.com/comics/ch/1989/ch891030.gif

- General references

- Greenhall, Arthur H. 1961. Bats in Agriculture. A Ministry of Agriculture Publication. Trinidad and Tobago.

- Nowak, Ronald M. 1994. " Walker's BATS of the World". The John Hopikins University Press, Baltimore and London.

- John D. Pettigrew's summary on Flying Primate Hypothesis

- Altringham, J.D. 1998. Bats: Biology and Behaviour. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dobat, K.; Holle, T.P. 1985. Blüten und Fledermäuse: Bestäubung durch Fledermäuse und Flughunde (Chiropterophilie). Frankfurt am Main: W. Kramer & Co. Druckerei.

- Fenton, M.B. 1985. Communication in the Chiroptera. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Findley, J.S. 1995. Bats: a Community Perspective. Cambridge: Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge.

- Fleming, T.H. 1988. The Short-Tailed Fruit Bat: a Study in Plant-Animal Interactions. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Kunz, T.H. 1982. Ecology of Bats. New York: Plenum Press.

- Kunz, T.H.; Racey, P.A. 1999. Bat Biology and Conservation. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Kunz, T.H.; Fenton, M.B. 2003. Bat Ecology. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Neuweiler, G. 1993. Biologie der Fledermäuse. Stuttgart: Georg Thieme Verlag.

- Nowak, R.M. 1994. Walker`s Bats of the World. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Richarz, K. & Limbruner, A. 1993. The World of Bats. Neptune City: TFH Publications.

External links

- Bat Conservation International

- Bats scan the rainforest with UV-eyes

- Bat Conservation International website

- Bat World Sanctuary

- Bat House, science popularization

- Bats Northwest - a non profit dedicated to education, research & conservation

- Texas Parks and Wildlife Bat Page

- University of Michigan Museum of Zoology

- Bats and Tarsier

- Tree of Life

- Bats make up 20% of mammals

- The Bat Conservation Trust

- Organization for Bat Conservation

- Illustrated Identification key to the (micro)bats of Europe (see "Recent publications")

- Lubee Bat Conservancy

- General text on bats

- Bat Research, Scotland, UK

- Microbat Vision

- [1]