Europa (moon)

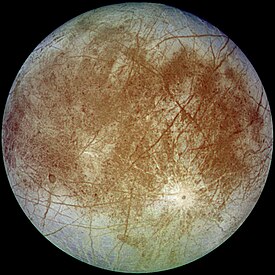

Europa, as seen by the Galileo spacecraft | |||||||||

| Discovery | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discovered by | G. Galilei S. Marius | ||||||||

| Discovery date | January 7, 1610 | ||||||||

| Orbital characteristics[1] | |||||||||

| Epoch January 8, 2004 | |||||||||

| Periapsis | 664,300 km (0.00444 AU) | ||||||||

| Apoapsis | 677,900 km (0.00453 AU) | ||||||||

Mean orbit radius | 671,079 km (0.004486 AU) | ||||||||

| Eccentricity | 0.0101 | ||||||||

| 3.551810 d (0.0097243 a) | |||||||||

Average orbital speed | 13.740 km/s | ||||||||

| Inclination | 1.78° (to the ecliptic) 0.464° (to Jupiter's equator) | ||||||||

| Satellite of | Jupiter | ||||||||

| Physical characteristics | |||||||||

| 1,560.8 km (0.245 Earths) | |||||||||

| 3.06×107 km² (0.060 Earths)[2] | |||||||||

| Volume | 1.593×1010 km³ (0.015 Earths) | ||||||||

| Mass | 4.80×1022 kg (0.008 Earths) | ||||||||

Mean density | 3.014 g/cm³ | ||||||||

| 1.314 m/s² (0.134 g) | |||||||||

| 2.025 km/s | |||||||||

| Synchronous[3] | |||||||||

| zero | |||||||||

| Albedo | 0.64 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| 5.3 | |||||||||

| Atmosphere | |||||||||

Surface pressure | 1 µPa | ||||||||

Europa (yew-roe'-pə, /jʊˈroʊpə/ ; Greek Ευρώπη) is the sixth nearest and fourth largest natural satellite of the planet Jupiter. Europa was discovered in 1610 by Galileo Galilei (and independently by Simon Marius shortly thereafter) and is the smallest of the four Galilean moons named in Galileo's honor.

Europa is primarily composed of silicate rock, has an outer layer of ice with probably some liquid water, and likely has an iron core. At just over 3000 kilometers in diameter, it is slightly smaller than the Earth's moon and the sixth largest moon in the solar system. The satellite has a very tenuous oxygen atmosphere and one of the smoothest surfaces in the solar system. The young surface of the moon is striated by cracks and streaks, while craters are relatively infrequent. Due to a hypothesized water ocean beneath its icy surface, and an energy source provided by tidal heating, Europa has been cited as a possible host of extraterrestrial life.[4] The heat energy ensures the ocean remains liquid and also drives geological activity.

The intriguing character of Europa has led to a number of ambitious exploration proposals; to date, only flyby missions have visited the moon. The Galileo mission provided the bulk of current data on the satellite, while the abortive Jupiter Icy Moons Orbiter, cancelled in 2005, was the most ambitious planned spacecraft. Conjecture on extraterrestrial life has ensured a high profile for the moon and led to continued lobbying for future missions.[5][6]

Discovery and naming

Europa was discovered in January 1610 by Galileo along with the three other large satellites of the planet Jupiter, Io, Ganymede, and Callisto; the discovery proved that Jupiter exerted an independent gravitational force, which helped buttress the emerging Copernican cosmology.[7] The satellites were apparently independently discovered by Simon Marius shortly afterwards (although there were allegations of plagiarism from Galileo) and he suggested the name after other nomenclature for the Jovian moons failed to catch on; he attributed the proposal to Johannes Kepler.[8][9] Europa is named after the mythological Europa, daughter of Agenor, king of the Phoenician city of Tyre (now in Lebanon), and sister of Cadmus, founder of Thebes, Greece.

The name fell out of favor for a considerable time (as did those of the other Galilean moons), and was not revived in common use until the mid-20th century.[10] In much of the earlier astronomical literature, it is simply referred to by its Roman numeral designation as Jupiter II (a system introduced by Galileo) or as the "second satellite of Jupiter". The discovery of Amalthea in 1892, closer than any of the other known moons of Jupiter, pushed Europa to third position. The Voyager probes discovered three more inner satellites in 1979, so Europa is now considered Jupiter's sixth satellite, though it is still sometimes referred to as Jupiter II.[10]

Orbit

Europa orbits Jupiter in just over three and a half days, with an orbital radius of about 670,900 km (416,900 mi). The satellite follows a very nearly circular orbit, with an eccentricity of only 0.009. Europa's orbital inclination relative to the Jovian equatorial plane is also slight, at 0.470°.[11]

Like all the Galilean satellites, Europa is tidally locked to Jupiter, with one hemisphere of the satellite constantly facing the planet. Research suggests the tidal locking may not be full, as a non-synchronous rotation has been proposed: Europa spins faster than it orbits, or at least did so in the past. This suggests an asymmetry in internal mass distribution and that "the surface is probably decoupled from the interior by a subsurface layer of liquid or ductile ice," in keeping with the proposed subsurface ocean.[12]

Because of its orbit's slight eccentricity, maintained by the gravitational disturbances from the other Galilean satellites of the planet, the sub-jovian point oscillates about a mean position. Europa strives to assume a slightly elongated shape pointing towards Jupiter in response to the tidal force of the giant planet; because different parts of Europa end up being on different points of this departure from sphericity at varying times, the crust flexes up and down. This motion dissipates energy from Jupiter's rotation into Europa (tidal heating), giving the moon a source of heat and energy, allowing the subsurface ocean to stay liquefied and driving subsurface geological processes.

Physical characteristics

Internal structure

Europa is somewhat similar in bulk composition to the terrestrial planets, being primarily composed of silicate rock. It has an outer layer of water thought to be around 100 km thick (some, as frozen ice upper crust; some, as liquid ocean underneath the ice), and recent magnetic field data from the Galileo orbiter probe, which orbited Jupiter and studied Europa between 1995 and 2003, shows that Europa generates an induced magnetic field by interacting with Jupiter's field, which suggests the presence of a subsurface conductive layer which is likely a salty liquid-water ocean. Europa probably also contains a metallic iron core.[13]

Surface features

Europa is one of the smoothest objects in the solar system.[14]; few features more than a few hundred metres high have been observed, but topographic relief in places approaches a kilometre (0.62 mi)[citation needed]. The prominent markings crisscrossing the moon seem to be mainly albedo features, which emphasize low topography. There are very few craters on Europa because its surface is active and young.[15][16] Europa's albedo (light reflectivity) of 0.64 is one of the highest of all moons because of its icy surface.[11][16] This would seem to indicate a young and active surface; based on estimates of the frequency of cometary bombardment that Europa probably endures, the surface is about 20 to 180 million years old[17] (the geological features of the surface clearly show a variety of ages[citation needed]). Cynthia Phillips, a member of SETI and an expert on Europa states there is currently no consensus among the often contradictory explanations for the surface features of Europa.[2]

Lineae

Europa's most striking surface feature is a series of dark streaks criss-crossing the entire globe. Close examination shows that the edges of Europa's crust on either side of the cracks have moved relative to each other. The larger bands are roughly 20 km (12 mi) across commonly with dark diffuse outer edges, regular striations, and a central band of lighter material.

Among the controversial hypotheses put forward to explain these features, one states that they may have been produced by a series of volcanic water eruptions or geysers as the Europan crust spread open to expose warmer layers beneath. The effect would have been similar to that seen in the Earth's oceanic ridges. These various fractures are thought to have been caused in large part by the tidal stresses exerted by Jupiter; since Europa is tidally locked to Jupiter, and therefore always maintains the same approximate orientation towards the planet, the stress patterns should form a distinctive and predictable pattern. However, only the youngest of Europa's fractures conform to the predicted pattern; other fractures appear to have occurred at increasingly different orientations the older they are. This could be explained if Europa's surface rotates slightly faster than its interior, an effect which is possible due to the subsurface ocean mechanically decoupling the moon's surface from its rocky mantle and to the effects of Jupiter's gravity tugging on the moon's outer ice crust. Comparisons of Voyager and Galileo spacecraft photos serve to put an upper limit on this hypothetical slippage of no faster than once every 10,000 years for the surface relative to its interior.

Other geological features

Another type of feature present on Europa are circular and elliptical lenticulae, Latin for "freckles". Many are domes, some are pits and some are smooth dark spots. Others have a jumbled or rough texture. The dome tops look like pieces of the older plains around them, suggesting that the domes formed when the plains were pushed up from below.

Among the controversial hypotheses put forward to explain these features, one states that these lenticulae were formed by diapirs of warm ice rising up through the colder ice of the outer crust, much like magma chambers in the Earth's crust. The smooth dark spots could be formed by melt water released when the warm ice breaks through the surface, and the rough, jumbled lenticulae (called regions of "chaos", for example the Conamara Chaos) would then be formed from many small fragments of crust embedded in hummocky dark material, perhaps like icebergs in a frozen sea.

Subsurface ocean

It is thought that under the surface there is a layer of liquid water kept warm by tidally generated heat. The temperature on the surface of Europa averages about 110 K (-163 °C) at the equator and only 50 K (-223 °C) at the poles, so the surface water ice is permanently frozen. The first hints of a subsurface ocean came from theoretical considerations of the tidal heating (a consequence of Europa's slightly eccentric orbit and orbital resonance with the other Galilean moons). Galileo imaging team members have analyzed Voyager and Galileo images of Europa to argue that Europa's geological features also demonstrate the existence of a subsurface ocean.[18] The most dramatic example is "chaos terrain," a common feature on Europa's surface that some interpret as a region where the subsurface ocean melted through the icy crust. This interpretation is extremely controversial. Most geologists who have studied Europa favor what is commonly called the "thick ice" model, in which the ocean has rarely, if ever, directly interacted with the surface.[19] The different models for the estimation of the ice shell thickness give values between a few hundred meters and tens of kilometers.[20]

The best evidence for the so called "thick ice" model is a study of Europa's large craters. The largest craters are surrounded by concentric rings and appear to be filled with relatively flat, fresh ice; based on this and on the calculated amount of heat generated by Europan tides, it is predicted that the outer crust of solid ice is approximately 10–30 kilometers (5–20 mi) thick, including a ductile "warm ice" layer, which could mean that the liquid ocean underneath may be about 100 km (60–65 mi) deep.[17] This leads to a volume of Europa's oceans of 3×1018m³, slightly more than two times the volume of Earth's oceans.

The so called "thin ice" model is a conclusion of the formation of ridges and the flexure of the ice shell due to loading at the surface. With these models the crust of solid ice could be as thin as 200 meters. The "thin ice" model allows regular contact of the liquid interior with the surface through open ridges.[20]

The Galileo orbiter has also found that Europa has a weak magnetic field (about one quarter the strength of Ganymede's field and similar to Callisto's) which varies periodically as Europa passes through Jupiter's massive magnetic field. A likely explanation of this is that there is a large, subsurface ocean of liquid salt water.[13] Spectrographic evidence suggests that the dark reddish streaks and features on Europa's surface may be rich in salts such as magnesium sulfate, deposited by evaporating water that emerged from within. Sulfuric acid hydrate is another possible explanation for the contaminant observed spectroscopically. In either case, since these materials are colorless or white when pure, some other material must also be present to account for the reddish color. Sulfur compounds are suspected.

Atmosphere

Observations with the Goddard High Resolution Spectrograph of the Hubble Space Telescope, first described in 1995, revealed that Europa has a very tenuous atmosphere composed mostly of molecular oxygen (O2).[21][22] At 1 micropascal surface pressure, or 10−11 that of the Earth's atmosphere at sea level, the atmosphere would "fill only about a dozen Houston Astrodomes."[22] The Galileo spacecraft confirmed the presence of a very tenuous ionosphere (an upper atmospheric layer of charged particles) in 1997, supporting the initial deduction of an atmosphere; solar radiation and the energetic particles of Jupiter's magnetosphere are responsible for the ionized layer around Europa.[23][24]

Unlike the oxygen in Earth's atmosphere, Europa's is not of biological origin. The "surface-bounded atmosphere" forms through radiolysis, the dissocation of molecules through radiation. Solar ultraviolet radiation and charged particles (ions and electrons) from the Jovian magnetospheric environment collide with Europa's icy surface, splitting water into oxygen and hydrogen constituents; chemical components are adsorbed and "sputtered" into the atmosphere. The same radiation also creates collisional ejection of these products from the surface, and the balance of these two processes forms an atmosphere.[25] Molecular oxygen is the densest component of the atmosphere because it has a long lifetime; after returning to the surface from a ballistic arc, it does not stick (freeze) to the surface like a water molecule or hydrogen peroxide molecule, rather it desorbs from the surface and starts another ballistic arc. Molecular hydrogen also does not freeze onto the surface, but is so light that it easily escapes Europa's gravity.

Observations of the surface have revealed that some of the molecular oxygen produced by radiolysis is not ejected from the surface. Since the surface may interact with the subsurface ocean (based on the geological discussion above), this molecular oxygen may make its way to the ocean, where it could aid in biological processes.[26]

Exploration

Most human knowledge of Europa has been derived from a series of flybys since the 1970s. The sister craft Pioneer 10 and Pioneer 11 were the first to visit Jupiter, in 1973 and 1974, respectively; the first photos of Jupiter's largest moons produced by the Pioneers were fuzzy and dim.[14] The Voyager flybys followed in 1979, while the Galileo mission orbited Jupiter for eight years beginning in 1995 and provided the most detailed examination to date of the Galilean moons.

Various proposals have been made for future missions. Any mission to Europa would need to be protected from the high radiation levels sustained by Jupiter.[5] The aims of these missions have ranged from examining Europa's chemical composition, to searching for extraterrestrial life in its sub-surface ocean.[27][28]

Possible extraterrestrial life

It has been suggested that life may exist in this under-ice ocean, perhaps subsisting in an environment similar to Earth's deep-ocean hydrothermal vents or the Antarctic Lake Vostok.[29] Life in such an ocean could possibly be similar to life on earth in the deep ocean.[27][30] So far, there is no evidence that life exists on Europa but due to the likely presence of liquid water, there are proposals to send a probe there.[31] Robert Pappalardo, an assistant professor within the University of Colorado's space department, said "We’ve spent quite a bit of time and effort trying to understand if Mars was once a habitable environment. Europa today, probably, is a habitable environment. We need to confirm this… but Europa, potentially, has all the ingredients for life… and not just four billion years ago… but today".[6] However, recent budget cuts have prevented proposed missions to search for life.[32]

Spacecraft proposals and cancellations

The plan for the extremely ambitious Jupiter Icy Moons Orbiter was cancelled in 2005.[32][5] The 2006 NASA budget includes Congressional language imploring NASA to fund a mission that would orbit Europa. Such a mission would be able to do the following:

- Confirm a subsurface ocean using gravity and altimetry measurements

- Elucidate the origin of surface features by imaging much of the surface at high resolution

- Constrain the chemistry of surface materials using spectroscopy

- Probe for subsurface liquid water using ice-penetrating radar.[33]

- Carry a small lander to determine the surface chemistry directly, and to measure seismic waves, from which the level of activity and ice thickness could be determined.

However, at present it is far from certain that NASA will actually fund this mission, as funding for it is not included in NASA's 2007 budget plan.[5][6][34] Planetary scientist Ronald Greeley said about the Europa mission:[6]

"I am disappointed that after so many false starts over the last decade, it looks like a mission to Europa is slipping once again. The planetary community remains essentially unanimous in setting Europa as the highest priority large mission to the outer solar system"

Additionally, NASA Chief Mike Griffin said the following about the Jupiter Icy Moons Orbiter:[6]

"It was not a mission, in my judgment, that was well-formulated. [A scientific mission to Europa] is extremely interesting on a scientific basis. It remains a very high priority, and you may look forward, in the next year or so, or maybe even sooner, to a proposal for a Europa mission as part of our science line. But we would not -- we would, again, not -- favor linking that to a nuclear propulsion system."

Another possible mission, known as the "Ice Clipper" mission, would use an impactor similar to the Deep Impact DI mission -- it would make a controlled crash into the surface of Europa, generating a plume of debris which would then be collected by a small spacecraft flying through the plume.[35] Without the need for an insertion and relaunch of the spacecraft(s) from an orbit around Jupiter or Europa, this would be one of the least expensive missions since the necessary amount of fuel would be decreased.[36]

More ambitious ideas have been put forward for a capable lander to test for evidence of life that might be frozen in the shallow subsurface, or even to directly explore the possible ocean beneath Europa's ice. One proposal calls for a large nuclear powered "Melt Probe" (cryobot) which would melt through the ice until it hit the ocean below.[37] The Planetary Society says that drilling a hole below the surface would be a main goal, and provide protection from radiation.[5] Once it reached the water, it would deploy an autonomous underwater vehicle (hydrobot), which would gather information and send it back to Earth.[38] Both the cryobot and the hydrobot would have to undergo some form of extreme sterilization to prevent it from detecting earth organisms instead of native life and to prevent contamination of the subsurface ocean.[39] This proposed mission has not yet reached a serious planning stage.[40]

Even though Congress, the National Academy of Sciences, and the NASA advisory committee have all supported a mission to Europa, funding has still been halted.[41][42] The Planetary Society plans to create an "International Europa Task Force" to convince NASA and other space agencies to fund a Europa mission.[43][44] Other people, such as Congressman John Culberson, have also tried to go against NASA's budget cuts.[45][46]

A "Solar System Exploration Roadmap" published for NASA by the Universities Space Research Association in 2006 placed exploration of Europa high on its list, and suggested that plans for a "flagship-class" mission to Europa begin by 2008 with hopes to launch by 2015.[47]

See also

- Jupiter's moons in fiction

- List of craters on Europa

- List of lineae on Europa

- List of geological features on Europa

- List of Jupiter's moons

- Colonization of Europa

References

- ^ "JPL HORIZONS solar system data and ephemeris computation service". Solar System Dynamics. NASA, Jep Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 2007-08-10.

- ^ Using the mean radius

- ^ See Geissler et al. (1998) in orbit section for evidence of non-synchronous orbit.

- ^ Tritt, Charles S. (2002). "Possibility of Life on Europa". Milwaukee School of Engineering. Retrieved 2007-08-10.

- ^ a b c d e Friedman, Louis (December 14, 2005). "Projects: Europa Mission Campaign; Campaign Update: 2007 Budget Proposal". The Planetary Society. Retrieved 2007-08-10.

- ^ a b c d e David, Leondard (February 7, 2006). "Europa Mission: Lost In NASA Budget". Space.com. Retrieved 2007-08-10. Cite error: The named reference "Europa2007Budget" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "Satellites of Jupiter". The Galileo Project. Rice University. 1995. Retrieved 2007-08-09.

- ^ "Simon Marius". Students for the Exploration and Development of Space. University of Arizona. Retrieved 2007-08-09.

- ^ Marius, S.; (1614) Mundus Iovialis anno M.DC.IX Detectus Ope Perspicilli Belgici, where he attributes the suggestion to Johannes Kepler

- ^ a b Marazzini, C.; (2005); The names of the satellites of Jupiter: from Galileo to Simon Marius, Lettere Italiana, Vol. 57, No. 3, pp. 391-407

- ^ a b "Europa, a Continuing Story of Discovery". Project Galileo. NASA, Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 2007-08-09.

- ^ Geissler, P. E. (1998). "Evidence for non-synchronous rotation of Europa". Nature. 391: 368. Retrieved 2007-08-09.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Kivelson, M. G.; et al.; Galileo Magnetometer Measurements: A Stronger Case for a Subsurface Ocean at Europa, Science, Vol. 289, No. 5483 (25 August 2000), pp. 1340-1343 (accessed 15 April 2006)

- ^ a b "Europa: Another Water World?". Project Galileo: Moons and Rings of Jupiter. NASA, Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 2001. Retrieved 2007-08-09.

- ^ Arnett, B.; Europa (November 7, 1996)

- ^ a b Hamilton, C. J. "Jupiter's Moon Europa".

- ^ a b Schenk, P. M.; Chapman, C. R.; Zahnle, K.; Moore, J. M.; Chapter 18: Ages and Interiors: the Cratering Record of the Galilean Satellites, in Jupiter: The Planet, Satellites and Magnetosphere, Cambridge University Press, 2004

- ^ Greenberg, R.; Europa: The Ocean Moon: Search for an Alien Biosphere, Springer Praxis Books, 2005

- ^ Greeley, R.; et al.; Chapter 15: Geology of Europa, in Jupiter: The Planet, Satellites and Magnetosphere, Cambridge University Press, 2004

- ^ a b Billings, S. E. (2005). "The great thickness debate: Ice shell thickness models for Europa and comparisons with estimates based on flexure at ridges". Icarus. 177 (2): pp. 397-412. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2005.03.013.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Hall, D. T.; et al.; Detection of an oxygen atmosphere on Jupiter's moon Europa, Nature, Vol. 373 (23 February 1995), pp. 677-679 (accessed 15 April 2006)

- ^ a b Savage, Donald (February 23, 1995). "Hubble Finds Oxygen Atmosphere on Europa". Project Galileo. NASA, Jet Propulsion Labratory. Retrieved 2007-08-17.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Kliore, A. J. (1997). "The Ionosphere of Europa from Galileo Radio Occultations". Science. 277 (5324): 355–358. doi:10.1126/science.277.5324.355. Retrieved 2007-08-10.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Galileo Spacecraft Finds Europa has Atmosphere". Project Galileo. NASA, Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 1997. Retrieved 2007-08-10.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Shematovich, V. I. (2003). "Surface-bounded oxygen atmosphere of Europa". EGS - AGU - EUG Joint Assembly (Abstracts from the meeting held in Nice, France). Retrieved 2007-08-10.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Chyba and Hand, "Life without photosynthesis" [1]

- ^ a b Chandler, D. L. (20 October 2002). "Thin ice opens lead for life on Europa". NewScientist.com.

- ^ Muir, H.; Europa has raw materials for life, NewScientist.com (22 May 2002)

- ^ Exotic Microbes Discovered near Lake Vostok, Science@NASA (December 10, 1999)

- ^ Jones, N.; Bacterial explanation for Europa's rosy glow, NewScientist.com (11 December 2001)

- ^ Phillips, C.; Time for Europa, Space.com (28 September 2006)

- ^ a b Berger, B.; NASA 2006 Budget Presented: Hubble, Nuclear Initiative Suffer Space.com (7 February 2005)

- ^ Hibbitts, K.; and Mullen, L.; Hitting Europa Hard, Astrobiology Magazine (May 1, 2006)

- ^ Tony Reichhardt (2005). "Designs on Europa unfurl". Nature. 437: 8. doi:10.1038/437008a.

- ^ Goodman, J.; Re: Galileo at Europa, MadSci Network forums, September 9, 1998

- ^ McKay C. P. (2002). "Planetary protection for a Europa surface sample return: The ice clipper mission". Advances in Space Research. 30 (6): 1601–1605.

- ^ Knight, W.; Ice-melting robot passes Arctic test, NewScientist.com (14 January 2002)

- ^ Bridges, A.; Latest Galileo Data Further Suggest Europa Has Liquid Ocean, Space.com (10 January 2000)

- ^ National Academy of Sciences Space Studies Board, Preventing the Forward Contamination of Europa, National Academy Press, Washington (DC), June 29, 2000

- ^ Powell, J. (2005). "NEMO: A mission to search for and return to Earth possible life forms on Europa". Acta Astronautica. 57 (2–8): pp. 579-593. doi:10.1016/j.actaastro.2005.04.003.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ NASA Budget Shuts Out Icy Moons Mission, SpaceDaily.com (February 08, 2006)

- ^ Berardelli, P.; AAS Pushing NASA To Rethink Its FY 2007 Budget, Space-Travel.com (May 5, 2006)

- ^ Projects: Europa Mission Campaign: Campaign Facts: International Europa Task Force, The Planetary Society

- ^ Projects: Europa Mission Campaign, The Planetary Society

- ^ David, L.; Lawmaker Campaigns Against NASA Budget Cuts, Space.com (16 March 2006)

- ^ Bourge, C.; Lawmakers steer NASA funding toward science mission, GovExec.com (July 31, 2006)

- ^ "Solar System Exploration: This is the 2006 Solar System Exploration Roadmap for NASA's Science Mission Directorate" (PDF). Universities Space Research Association. September 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help)

External links

- Europa, a Continuing Story of Discovery at NASA/JPL

- Europa Profile by NASA's Solar System Exploration

- The Calendars of Jupiter

- Are our nearest living neighbours on one of Jupiter's Moons?