First-person shooter

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2007) |

This article may be written from a fan's point of view, rather than a neutral point of view. |

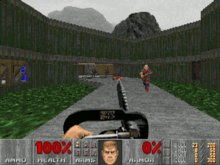

A first-person shooter (FPS) is a video game that renders the game world from the visual perspective of the player character and tests the player's skill in aiming guns or other projectile weapons. In the modern era of video games, key technologies such as 3D graphics, online play, and modding were first showcased by FPS. Enhanced realism combined with graphic violence has also made FPS a common topic in ongoing controversies over video games.

Overview

The first-person shooter is a sub-genre of shooter games. Many other shooter genres, such as on-rails shooters, are viewed from a first-person perspective, while flight simulators frequently involve the use of weapons; however, these are not considered FPSs. In the early 1990s, the term came to define a more specific type of game with a first-person view, where the main character's gun and part of his/her hand is shown, almost always centered around the act of aiming and shooting handheld weapons, usually with limited ammunition. The focus is generally on the aiming of one's own guns and the avoidance of enemy attacks, but the player is given more control over their movement than in on-rails shooters and most light gun games.

Many third-person shooters (where the player sees the game world from a viewpoint above and behind the main character) are commonly treated as first-person shooters, due to similarities in gameplay. In some cases (for example, Unreal Tournament 2004, Command & Conquer: Renegade, Star Wars Battlefront II, Oddworld: Stranger's Wrath or Duke Nukem 3D) it is possible to toggle the game between viewpoints and play the entire game from either perspective.

More frequently, a first-person view will be adopted in a third-person game only for brief periods for certain situations when it is advantageous. Since a first-person view usually allows more precise refinement of a player's aim than most third-person aiming systems, many third-person shooters allow the player to switch to their avatar's viewpoint in order to fire a weapon; sometimes, as in the first Metal Gear Solid title and Grand Theft Auto III, this may only be done when specific weapons (a sniper rifle, for example) are equipped. In addition, certain third-person shooters such as Burning Rangers let the player switch to a first-person perspective in order to observe their surroundings, but do not allow them to shoot any weapons while using it. Some first-person games switch by default to a third-person view when a melee weapon, such as a sword or a lightsaber, is selected (as in LucasArts' Jedi Knight) on the theory that a wider perspective makes those weapons easier to manage.

Gameplay

All FPSs feature the core gameplay elements of movement and shooting, but many variations exist, with different titles emphasising certain aspects of the gameplay. The lines between sub-genres are not distinct; some games include stealth elements in addition to action-packed sequences more typical of a "run and gun" FPS. Steven Poole commented that Half-Life "edged [the FPS] into the grey zone between shoot 'em up, exploration and puzzle games."[1] Deus Ex was also praised for giving players the ability to choose the approach they took to situations in the game.[2]

Realism

Settings may vary from accurate recreations of historical periods such as World War II to fantastic sci-fi depictions of the distant future. Damage to the player and enemies may be modeled fairly realistically, with the possibility of dying by a single shot, or wounds to different body parts having a visible effect on the gameplay. A very common simplification of the main character's overall condition is to represent it as two sets of hit points: a base "health" meter representing the "naked" character's vitality, and another gauge measuring external protection provided by body armor or shields.

The type of weaponry found in an FPS, and the realism of guns' accuracy and power, is usually appropriate to that game's setting. Frequently, the most recently-found gun will be the most powerful, and players will retain every weapon they have discovered, ending the game carrying an unrealistically massive arsenal of guns and ammunition. However, developers have also attempted to improve the realism of their games by placing a limit on the number of weapons players may carry.

Some FPS games strive to increase visual realism while retaining unrealistic gameplay. As a result, in many games the player has exaggerated physical capabilities and resiliency, such as surviving a tank shell or falling 15 feet without a scratch.

Structure

Most FPSs employ the videogame convention of being split into distinct levels separated in time and space, each set in a specific environment such as a warehouse, desert, laboratory, or castle. The linearity of FPSs also varies, with some leading the player as directly as possible through the game through as many gunfights as possible, while others give the player numerous options regarding how they tackle each section. More recent titles have allowed the player to wander around large sandbox environments.

Combat and pacing

Many FPSs maintain a focus on "run and gun" gameplay, with quick movement and near constant combat. Other titles adopt a slower pace, with the emphasis on puzzle-solving, or interaction with characters in ways other than combat.

- Stealth is a common feature of FPSs — firefights in some FPSs are extremely risky and require the player to avoid detection. But even in games that feature numerous shootouts, sneaking up on an unaware opponent can be an advantageous technique. In addition, these games also have non-ranged weapons.

- Strategy and planning are emphasised in tactical shooters and military simulations. These often allow the player to fight alongside and issue commands to squads made up of AI-controlled companions or human teammates. There have also been games that blend Real-time strategy gameplay to FPSs. In these games, the player appears on the field as a single unit, but is able to give commands to other units, construct new units, and control the overall strategy. Some RTS/FPS hybrids use teamplay approach where one player is the commanding officer, responsible for the strategy part, and the other team members are ordinary soldiers.

Multiplayer

Many first-person shooters are designed primarily as multiplayer games, and the single-player component (if any) consists entirely of play against bots. The MMOFPS combines first-person shooter gameplay with a large number of simultaneous players over the Internet. Most FPSs feature competitive and/or co-operative online multiplayer modes. Players of these games often form into teams, or "clans" and participate in organized tournaments and championships.

Modding

Many FPS games are designed with a core game engine, separate from the graphics, game rules, and levels. This "plug-in" design allows users to add new content to games. This has contributed to the longevity both of the genre and of individual games. Many games now include the custom software that the designers themselves used in the game's production. Some of the skills displayed by individual modders are of such high quality that FPS companies regularly hire new talent from the modding community.

Control systems

Keyboard and mouse

Most modern first-person shooters on the PC utilise a combination of the WASD keys of the keyboard and mouse as a means of controlling the game (commonly referred to as "WASD/Mouse"). Usually FPS control schemes are fully customizable within the game.

One hand uses the mouse, which is used for free look (also known as mouse look), aiming and turning the player's axis. The primary mouse button is used for the main "fire" function, with any additional buttons on the mouse performing other actions such as secondary fire functions, grenade throwing, mélée attacks, or activation of a zoom lens. A scroll wheel is often used to change weapons.

On the keyboard, the arrow keys (or other keys arranged in the same manner, such as WASD, ESDF or IJKL) provide digital movement forwards, backwards, and sidestepping (often known as "strafing" among players) left and right. Usually these buttons make the player run, and a nearby button must be pressed in order to walk. Other nearby keys perform additional functions such as crouching, jumping, opening doors, reloading, and picking up and dropping weapons. The R key is the Reload Weapon key in most FPS default keyboard configurations.

Control pads

Although some game consoles such as the Dreamcast include support for keyboard and mouse peripherals, allowing the above control systems to be used, the majority of console FPSs are controlled by the system's standard control pad. Early console FPSs such as Zero Tolerance and Corporation were restricted by the number of keys available on the standard control pad and their digital nature; in the former, the Mega Drive D-pad controlled turning and forward and backward motion, with the four directions combined with the press of another button performing additional jumping, crouching and sidestepping movements.

On more recent control pads with two analog sticks (such as Sony's DualShock 1 and 2 and Sixaxis PlayStation 3 controllers, and the Xbox, Xbox 360 and GameCube pads), four main control systems have come about. In the case of control pads with only a single analog stick (as with the Nintendo 64 and Dreamcast), the functions of one of the sticks may be transferred to four of the face buttons, although this only provides digital movement in those four directions, without the pressure-sensitive precision of an analogue stick.

- 1

- (Commonly known as the Halo style of controls, although other games before Halo have implemented it)

- Left analog stick: Used for movement

- Up and down: Movement forward and backward.

- Left and right: Lateral sidestepping ("strafing").

- Right analog stick: Used for free look

- Up and down: Vertical aiming.

- Left and right: Rotation left and right.

- 2

- (Commonly known as the original, old-style, or legacy)

- Left analog stick:

- Up and down: Movement forward and backward.

- Left and right: Rotation left and right.

- Right analog stick:

- Up and down: Vertical aiming.

- Left and right: Lateral sidestepping ("strafing").

- 3 and 4

- Two further control schemes in which the functions of the left and right analog sticks are swapped.

Not all FPSs allow the default control scheme to be fully customised, but usually all of the above may be further modified. Often there is an option for players who wish prefer to "invert" their aiming, so that pressing down on the vertical aiming analog stick makes their aim move up (like pulling "back" on the joystick in a flight simulator), and pressing up ("forward") on the same stick moves their aim down.

Usually, firing a gun is performed by pressing one of the shoulder buttons or triggers on the control pad, an action similar to pulling the trigger on a real gun. Sometimes, however, shooting may be set to one of the face buttons, which are usually used for other functions such as crouching, reloading or opening doors. Switching weapons is generally performed by pressing left and right on the D-pad.

Wii remote

Games released or in development for Nintendo's Wii console include Metroid Prime 3: Corruption, Far Cry: Vengeance, Call of Duty 3, Medal of Honor: Vanguard and Red Steel, five first-person shooters which use the motion-sensitive Wii Remote as an aiming device instead of the traditional mouse or analog stick. Movement is controlled with the analog stick on the Wii Remote's "Nunchuk" attachment.

Nintendo DS

In FPS games for the Nintendo DS, (such as Metroid Prime Hunters) the D-pad is used for walking and strafing, while the touch screen is used similar to a mouse for aiming. Shooting is usually used with the L button, but some games, like Metroid Prime Hunters, have left handed configurations.

Platforms and hardware development

The primary platform for modern FPSs has traditionally been the PC, though there have been notable games on other platforms, and the number of releases on consoles are increasing steadily.

FPS are among the most demanding programs for computing resources, persuading many users to upgrade computers that are still suitable for more mundane tasks, such as online browsing and office work. According to IDC analyst Roger Kay, high-end games serve as a catalyst for the mainstream personal computer market. FPS games can stretch the capabilities of CPUs and the graphics cards ([1]). The rise of the genre has been a significant driver in the market for consumer graphics cards, particularly with regard to support for hardware acceleration of 3D graphics. Recently, consumer HMDs have been introduced which should further drive developments in virtual reality technology and better game play by providing a more immersive experience.

History

The first-person shooter, as the phrase is currently understood, emerged in the early 1990s. However, the modern genre is an extension of earlier games, particularly those involving 3D graphics. While these early games are not First-Person Shooters in the modern sense, many of them come very close in gameplay terms, and many others contained ideas which later influenced the modern genre.

Beginnings

It is not clear exactly when the first FPS was created. There are two claimants, Spasim and Maze War. The uncertainty about which was first stems from the lack of any accurate dates for the development of Maze War — even its developer cannot remember exactly. In contrast, the development of Spasim is much better documented and the dates more certain.

The initial development of Maze War probably occurred in the summer of 1973. A single player made their way through a simple maze of corridors rendered using fixed perspective. Multiplayer capabilities, with players attempting to shoot each other, were probably added later in 1973 (two machines linked via a serial connection) and in the summer of 1974 (fully networked).

Spasim was originally developed in the spring of 1974. Players moved through a wire-frame 3D universe, with gameplay resembling the 2D game Empire. Graphically, Spasim lacked even hidden line removal, but did feature online multiplayer over the world-wide university-based PLATO network. Another notable PLATO FPS was the tank game Panther, introduced in 1975.

1979-1990: Arcades and home computers

The next significant games arrived in the video arcade boom of the late 1970s. The 1979 game Tail Gunner was the first commercial shooter game to provide a first-person perspective. Players could not move through the simulated world, but fought off opponents from a fixed point in space.

1980s Battlezone, a tank combat simulator reminiscent of Panther, allowed players to move around the game world in their battle with computer-controlled enemies, and thus became the earliest widely-available first-person shooter in arcades. It was a resounding commercial success.

In the early 1980s, the home computer market grew rapidly. While these machines were relatively low-powered, limited first-person-perspective games appeared early on. Star Raiders (1979) gave the player the perspective of a spaceship pilot flying through a streaming 3D starfield; motion was unrestricted, but the environment consisted only of stars and individual moving objects, with no 3D scene rendering at each individual frame. 3D Monster Maze (1981) for the Sinclair ZX81 was the first truly 3D first-person adventure game on a home computer, although not a shooter. Dungeons of Daggorath and Phantom Slayer (1982) restricted the player to 90-degree turns, allowing "3D" corridors to be drawn with simple fixed-perspective techniques. In these games, computer-controlled opponents were drawn using bitmaps. 3D Deathchase (1983) on the ZX Spectrum featured a 3D shooter chase through a forest, with the 3D being created using drawings of trees getting larger as they moved closer to the player. Similar to Phantom Slayer, the 1983 game 3-Demon was a 3D version of Pac-Man for the IBM PC situating the player first-person inside the PacMan maze.

Numerous other "tricks" were used by programmers to simulate 3D graphics. Examples include two early games from Lucasarts, Rescue on Fractalus! (1984) which used fractal techniques to generate an alien landscape for the player to fly over, and The Eidolon (1985) which scaled simple bitmaps to create the illusion of 3D. Other good examples of 8-bit first-person 3D games are Pete Cooke's ZX Spectrum titles Tau Ceti (1985) and Micronaut One (1987), the former having a 3D planetary environment and the latter involving the player's ship traveling through wireframe tunnels.

Later in the decade, the arrival of a new generation of home computers such as the Atari ST and the Amiga increased the computing power and graphical capabilities available, leading to a new wave of innovation.

Although it lacked numerous modern graphical features including textures, varying colors, and the use of special shading techniques to simulate curved polygons, the first first-person shooter to offer true-3D filled-polygon graphics was the single-player Driller, released in 1987, which used the acclaimed Freescape engine. Other FPS games of the flat-polygon era include Faceball 2000, The Colony, and MIDI Maze, the latter notable for its networked multiplayer feature (communicating via the computer's MIDI interface).

1991-1993: Defining the genre

By 1990 the technology to render very simple flat-colored 3D worlds was widespread, and was being used extensively in simulator games such as Abrams M1, LHX Attack Chopper, and others.

In April 1991, the then-unknown id Software released Hovertank 3D. This game innovated a new rendering technique called raycasting, whereby vertical lines are scaled to create a smooth 3D perspective as long as the player looks straight ahead (raycasting games do not allow players to look up and down, though later games would fake this to various degrees of success). The game environment was a simple flat grid-based map, with enemies rendered as sprites. Later the same year, a modified version of the same game engine, adding texture-mapped walls, was used in Catacomb 3D, which also introduced the concept of showing the player's hand on-screen, strengthening the illusion that the player is literally viewing the world through the character's eyes.

In 1992, id improved the technology by adding support for VGA graphics in Wolfenstein 3D which surprisingly was created by only 13 people in 2 months. With these improvements over its predecessors, Wolf 3D was a hit, and marked the emergence of the modern FPS genre.

A lesser-known predecessor to Wolfenstein 3D is Ultima Underworld (1992), a role-playing game developed by Blue Sky Productions, (later merged with another developer to create Looking Glass Studios) and marketed by Origin Systems. Unlike Wolfenstein 3D, Ultima Underworld supported many true 3D features such as non-perpendicular walls, walls of varying heights, and inclined surfaces. A technology demo of this game was, in fact, John Carmack’s inspiration for Wolfenstein 3D’s game engine. [2]

In 1993, Pathways into Darkness was released by Bungie. It mixed the elements from a FPS with those of a RPG. While this had been done in Ultima Underworld, Pathways into darkness focused more on its shooter elements where as Ultima Underworld was more of an RPG in first person. The game was the first FPS to include and fully integrate a complex and complete story throughout the game. However, Pathways only experienced limited commercial success, partially due to its difficulty level, but mainly due to being available only for Apple computers. It is considered the spiritual ancestor of the Marathon and Halo series developed by Bungie[citation needed].

Wolfenstein 3D was soon surpassed by id's next game, the genre-defining Doom (1993). While still using sprites to render in-game opponents, and raycasting to render the levels, Doom added texture-mapping to the floor and ceiling, and removed some of the restrictions of earlier games. Walls could vary in height, with floor and ceiling changing levels to create cavernous spaces and raised platforms. In some areas, Doom removed the ceiling altogether to create the outdoor environments that were generally lacking in previous genre games. However, Doom wasn't truly 3D; id used a line map system which the game would make into a 3D looking environment, and they added the height later; this meant they couldn't put a room on top of a room, but they could create an Automap more easily.

While the graphical enhancements were notable, Doom's greatest innovation was the introduction of network multiplayer capabilities. While similar multiplayer modes had existed in previous mainframe- or arcade-based games, Doom was the first mass-market game to gain a significant following dedicated to multiplayer (usually, but not exclusively, LAN-based) contests, and guaranteed persistence of the FPS in gaming formats; the real thrill of these already-atmospheric games comes from blasting human opponents, be they friends or strangers on the Internet. Doom was also one of the earliest FPS games to gain an active community of fans producing add-on maps.

1994-2000: After Doom

Doom dominated the genre for years after its release. Every new game in the genre, such as Heretic, was held up against its masterpiece, and usually suffered by comparison. However, some developers wisely chose not to attack Doom head-on, but instead to concentrate on its weaker aspects, or expand the new genre in alternative directions.

Marathon (1994), together with its sequels Marathon 2: Durandal (1995) and Marathon Infinity (1996) by Bungie Studios, added AI controlled teammates/friendly combatants, unarmed/ambient characters, dual wielding, secondary functions on weapons, and free look as it is known today. It also allowed one polygon (the Marathon equivalent of a sector) to be placed over another and one character to pass over/under another, this made much more complex architecture and game play possible. However, these games did not reach a wide audience, being released only on the Apple Macintosh platform at the time.

The 1995 game Descent used a fully 3D polygonal graphics engine to render opponents (previous games had used sprites). It also escaped the "pure vertical walls" graphical restrictions of earlier games in the genre, and allowed the player six degrees of freedom of movement (up/down, left/right, forward/backward, pitch, roll and yaw). Thus, Descent was the first FPS in the modern era to use a fully 3D engine. However, because the player character is in actuality a space vehicle, Descent is not always considered an FPS in the traditional sense and may be classified as a space-sim hybrid.

Duke Nukem 3D, released in 1996, was the first game using what proved to be the most popular engine of the decade (12 released titles), Ken Silverman's Build engine. Build was outwardly similar to Doom's engine in that it used many 2D tricks, but was somewhat more advanced in this regard. It introduced the ability for players to swim and fly using a jetpack. Duke, and Build, are also notable for having one of the simplest map editors of any 3D game ever made.

In 1996 id Software released their eagerly-anticipated Quake which significantly enhanced the network gaming concept introduced by Doom. Like Descent, it used a 3D polygonal graphics engine to render enemies, but also added support for hardware-accelerated 3D graphics with GLQuake. In addition, id released an internet-optimized network client called QuakeWorld. Quake also actively encouraged user-made modifications. These "mods" contributed to its longevity and popularity with players; the most important of these was Threewave's CTF mod, which defined the now-standard Capture the Flag mode found in many FPS games.

In 1997, GoldenEye 007 was released for the Nintendo 64. It was praised for a realistic setting, incorporating impressive artificial intelligence and animation, elaborate bullet-hit detection (permitting a player to inflict maximum damage through accurate "head shots"; a practice encouraged through the incorporation of a "sniper scope" weapon function), and mission objectives and well-designed environments based on the GoldenEye film's sets. Its split screen multiplayer deathmatch mode was also well-regarded for the range of options offered. Console first-person shooters have for many years been criticized for having control schemes less precise than the keyboard and mouse of PC titles, yet GoldenEye overcame such complaints to be considered the first great FPS for a console, as well as one of the best movie-to-game adaptations.

In 1998, the game Half-Life was released, featuring a single-player game with a narrative focus directing the action and the goals of the player. The tremendous success of the game encouraged the creation of many more games with a similar focus on story-based action. Half-Life also resulted in many successful mods, such as the hit Counter-Strike. Counter-Strike continues, nine years later, to be the most popular multi-player FPS in the world.

Another game of 1998, Starsiege: Tribes, was the first attempt to create a large, team-based arena FPS requiring strategic coordination. Supporting large numbers of players, vehicles, wide-open landscapes and movement mechanics provided by the jetpack all players spawned with, Tribes can be considered the ancestor of shooters like Battlefield 1942 and contributed greatly to the creation of the massively multiplayer FPS genre. This game also spawned a large functionality based modding community, that created numerous ui changes and scripts that made play easier, including complicated inventory management scripts, and movement aides.

1999 was another important year for FPS, as two competing franchises were pitched head-to-head: Quake III Arena and Unreal Tournament. At this point both franchises concentrated on multiplayer gameplay over a LAN or the internet, reducing the single player experience to arena-based bot matches.

The 2000s: Strides for Realism

In 2000, Deus Ex was released, a single-player FPS that blended elements from RPG and adventure games. It featured many side-quests and multiple ways of completing each mission. This game also had a character building system similar to an RPG where the player gained experience points for completing various objectives, which were then spent on upgrades for your character, as in the System Shock games. Additionally, it incorporated stealth elements that first appeared in Thief: The Dark Project.

In 2001, Operation Flashpoint was released, creating a new level of realism in an FPS environment with extensive vehicles and aircraft, seamless indoor / outdoor environments, and view distances an order of magnitude longer than anything else released before it in the genre.

Halo: Combat Evolved was released for the Xbox. The game was acclaimed for its artificial intelligence in enemies, popularising features such as melee combat and recharging health, and standardising an FPS control scheme for consoles.

Return to Castle Wolfenstein, another 2001 release. RTCW was the sequel to the original Wolfenstein, and continued the story of the original game. The game featured more of a run-and-gun style of play, but was not grossly unrealistic in terms of the players survivability. Like many of id's titles, though, the player was not restricted to the number of weapons carried, although heavy weapons would slow down their movement speed. The plot was drastically expanded upon, playing off of real world aspects of Nazi mysticism and occult research.

Of particular note is RTCW's multiplayer mode, which while not the first of its kind can definitely be mentioned as "standing out" from other titles. Players selected from one of four classes, each with different abilities and weapons. All 4 types were critical to victory, due to the objective-based nature of the multiplayer maps. Simply put, "deathmatch" did not exist, and each map consisted of a series of objectives that needed to be completed by the players in order to achieve success.

Also released in 2001, World War 2 Online (WWIIOL) was released, expanding the FPS genre to a massively multiplayer audience. Unlike most FPS games of the time, which had limits of 32 players, WWIIOL could support thousands of simultaneous players. As such, WWIIOL is recognized as the pioneer of the MMOFPS (Massively-Multiplayer Online First-Person Shooter) sub-genre. Placed in a WWII setting, players could compete in realistically modeled tanks, airplanes, ships and infantry of the WWII era on a massive 1/2 scale map of Europe.

In 2002 Battlefield 1942 was released, including easily-operated vehicles, aircraft, and ships. The game featured a class-based infantry combat system in a World War 2 setting and proved to be a highly popular multiplayer game, setting the stage for its sequels, Battlefield Vietnam, Battlefield 2 and Battlefield 2142 (and the upcoming Battlefield: Bad Company). In contrast to the somewhat similar and recently released WWIIOL, the game was focused a bit more on fast-paced and visually pleasing action and a smaller number of players, putting less emphasis on a massively multiplayer world and realism in equipment modelling.

Meanwhile, in the world of consoles, Metroid Prime was released. It was a quasi-FPS with platforming and third-person elements for the Nintendo GameCube, set in a comparatively large world that focused more on exploration than combat; it also featured a unique approach to plot narration through a "scan" mechanic, which allowed the player to piece together the story and the game's myriad background details by examining enemies, computer screens and other objects. It utilized a lock-on based targeting system similar to that used in Nintendo's first-party title The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time. Due to its weighting towards exploration, typical of the Metroid series' style, many critics referred to the title as a first-person adventure game.

During 2004 through 2006, many remakes of older games were released, along with some newcomers:

- Doom 3: Made use of a new graphics engine featuring hitherto unseen real-time lighting and shadows, used exclusively to create an atmosphere of fear and danger for the player. Essentially a "re-telling" of the original Doom story, and in many ways a throwback to some of the techniques used in earlier FPSes, the main selling point for the game was actually its graphics engine. Using cutting-edge technologies, id Software created one of the most powerful graphics engines to date[citation needed]. As with previous Doom and Quake engines, it is being widely licensed to developers.

- Half-Life 2: Making extensive use of shaders, advanced lighting, 3d textures, AI with squad tactics, Havok middleware physics engine and relatively large maps for its level of graphic detail. The level of detail seen in the game is perhaps best exemplified by the complex character facial models developed especially for the game. The behind-the-scenes character engines can use voice recognition software, and the mouths of the models in the game will move according to what the character is saying and will express emotions when combined with script.

- Painkiller: Featured extremely fast-paced gameplay and high-resolution textures.

- Far Cry: Utilized an engine which rendered extremely large outdoor environments, as well as lighting and shader effects and advanced AI.

- Halo 2: The sequel to Halo: Combat Evolved had new features such as hijacking vehicles, and was also one of the few console games to have an expansion pack released for it.

- F.E.A.R. - First Encounter Assault Recon: Developed by Monolith Productions using a revamped version of their Lithtech engine, F.E.A.R. combined intense first-person shooter action with a distinctive horror theme.

- Metroid Prime Hunters: Another continuation of the Metroid Prime series on the DS, Hunters is the first major handheld FPS. Though it has some of the explorative elements of its console based predecessors, it has been praised for its combat system, and for proving that handhelds can host superb FPS games. The game has online multiplayer, and is one of the most popular games on the Nintendo Wi-Fi Connection.

There have been many attempts to combine the FPS genre with role-playing (RPG) or real-time strategy (RTS) games. The Half-Life mod Natural Selection blended a multiplayer FPS with some RTS elements. Wolfenstein: Enemy Territory blended some RPG elements with an experience and skill-based point system that can work across matches. Battlefield 2 has a stats tracking similar to Enemy Territory, and a complicated scoring system. The Wheel of Time attempted to blend a FPS with an RPG and was one of the few fantasy games to be a first-person shooter as most fantasy games are RPG's.

The Nintendo Wii, which uses the motion-sensitive Wii Remote, approaches the genre from a new direction. First person shooters like Red Steel and Call of Duty 3 use the remote as its gun-pointing input. Metroid Prime 3: Corruption, is said to have a control scheme very close to a PC First Person Shooter control scheme. The success of such a format is not yet decided but opens the way for more innovative gameplay in the FPS genre.

Controversy

Critics argue that the first-person perspective adds a level of imitable realism to the act of killing, and that FPS desensitizes gamers to this sort of behavior. The most widely publicized link between FPS and real-world violence is the Columbine High School massacre. Both of the shooters were fans of Doom, and Eric Harris had actually published a set of Doom levels on his website; the levels are now known as the "Harris levels".

See also

- WASD

- Free look

- Lists of video games

- First-person shooter engine

- MMOFPS

- List of free first-person shooters

- First-person narrative

- Total conversion

References

- ^ Poole, Steven (1999) [2000]. Trigger Happy (2nd edition ed.). London: Fourth Estate Limited. p. 38. ISBN 1-84115-121-1.

As processing power increased in the 1990s the genre definitively broke the bounds of flat-plane representations with the emergence of the 'first-person shooter', exemplified by Doom and its multifarious clones. … This, a sub-genre that traces its roots back to Atari's 3D tank game Battlezone (1980) ousted its two-dimensional counterparts as king of the hill, at the same time adding rudimentary quest and object-manipulation requirements which—especially as environments and programmed enemy cunning became more complex, as in the extraordinary Half-Life (1998)—edged it into the grey zone between shoot 'em up, exploration and puzzle games.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameters:|origmonth=,|month=,|chapterurl=,|coauthors=, and|origdate=(help) - ^ Gillen, Kieron (2005-05-20). "Deus Ex". Retrieved 2006-09-13.(Originally published in PC Gamer (UK) issue 87.)