Alabama Cooperative Extension System

This article contains content that is written like reads very much like a promotional brochure or website in several areas. (January 2008) |

| File:Alabama-extension-logo.jpg Official Alabama Cooperative Extension System logo (2008) | |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | 1914 |

| Jurisdiction | Alabama |

| Headquarters | Auburn, Alabama and Normal, Alabama |

| Employees | 800 |

| Annual budget | $30 million |

| Agency executives |

|

| Parent agency | Alabama A&M University and Auburn University |

| Website | http://www.aces.edu/ |

The Alabama Cooperative Extension System provides educational outreach to the citizens of Alabama on behalf of the state’s two land grant universities: Alabama A&M University, the state’s 1890 land-grant institution, and Auburn University, the 1862 land-grant institution.[1]

The system employs more than 800 faculty, professional educators and staff operating in offices in all of Alabama’s 67 counties and in nine urban centers located in major regions of the state.[2][3] In conjunction with the Alabama Agricultural Experiment Station, the system also staffs six Extension and Research Centers located in all of the state’s principal geographic regions.[2]

Since 2004, Alabama Extension has functioned primarily as a regionally-based system through which the bulk of educational programming is delivered by agents operating across a multi-county area and specializing in a particular field. Even so, county Extension coordinators and, in cases where funding is available, county agents, continue to play integral roles within the Extension mission, working with regional agents and other Extension personnel to deliver services to clients in their areas.[2]

Alabama Extension, which will mark its centennial in 2014, possesses a history deeply rooted in the impoverished post-Civil War conditions of the rural Deep South. When the foundations of Extension work were being laid in the state, Alabama was still reeling from the lingering economic dislocation and depravation associated with post-war conditions.[4] A major focus of Extension work at that time was on using cutting-edge research from the state’s expanding land-grant university system in tandem with emerging Industrial Age technology to improve the working conditions of the state’s farmers and homemakers.[5]

Today, Alabama Extension faces many of the challenges also common among Extension programs in other states, namely rethinking and expanding its mission to address the needs of a state that is increasingly more affluent, urbanized and racially and ethnically diverse. Many of Alabama Extension’s priority program areas are targeted to traditional audiences in rural parts of the state, but an increasing focus is on reaching nontraditional clients in urban areas of Alabama.[6]

Moreover, capitalizing on rapid advances in communications technologies, Alabama Extension, like many of its counterparts in other states, increasingly is expanding its mission to reach regional, national and even worldwide audiences.[1]

Distinctive programs

The Alabama Cooperative Extension System’s six outreach emphases are agriculture, forestry and natural resources, urban and new nontraditional programs, family and individual well-being, community and economic development, and 4-H and youth development. These five areas of emphasis encompass 14 priority programs. While many of these priorities areas are reflected in Extension efforts in other states, Alabama’s history often has channeled Alabama Extension programming efforts into program areas that are not replicated by other states.[6]

Agriculture

Alabama Agriculture and Forestry Leadership Development Program

The oldest program of its kind in the Southeast, the Extension-sponsored Alabama Agriculture and Forestry Leadership Development program, known as LEADERS, graduated its eighth class in 2007. The two-year course of study seeks to prepare its graduates to become effective spokespersons on behalf of the Alabama food and fiber sector. More than 200 Alabamians, selected from the state’s agriculture and forestry industries, have graduated from the program. [7]

Beef Quality Assurance

Alabama Extension was a pioneer in the Beef Quality Assurance program, a voluntary quality control program through which beef producers learn and implement management practices designed to ensure beef product quality. The Extension-sponsored BQA program is a cooperative effort among beef producers, veterinarians, the Alabama Veterinary Medical Association and the Alabama Cattlemen’s Association.[8]

Master Gardeners

The Alabama Master Gardener Program, which marked its 25th anniversary in 2006, is one of Cooperative Extension’s longest running volunteer efforts. The program recruits people with an interest in gardening to commit to 40 hours of intensive coursework in horticulture and, upon completion of this training, to devote at least 40 hours of volunteer service to the community.[9]

Precision farming

With financial support of farmers and farm commodity organizations, Alabama Extension also has emerged as an early adopter of precision farming practices. Using a network of orbiting satellites, the technology enables producers using specially designed receivers to compile detailed soil maps and yield histories, which, in turn, have allowed them to post substantial savings in farm chemical applications and labor costs.[10]

Extension has worked with farmers and counterparts in the Alabama Agricultural Experiment Station to establish demonstration farms and research fields to test this new technology.[11]

Forestry and Natural Resources

Professional Logging Certification

Alabama Extension-sponsored logger training helps logging professionals maintain certification to remain employed in the state’s multi-billion-dollar forestry industry. Extension contributes to about 15 percent of the 12,000 hours of continuing education accumulated annually by Alabama loggers.[10]

Urban and New Nontraditional programs

An increasing emphasis of Extension programming within the last decade has been on urban and new nontraditional programs, focusing on the two-thirds of Alabamians who now live in urban areas. The Urban and New Nontraditional programs are administered through eight urban centers and two satellite offices throughout the state. Major emphases include the urban family network, workforce preparation, domestic violence prevention, teen leadership, health, and nontraditional agriculture.[12]

Urban-Rural Interface Conference

The Urban-Rural Interface Conference, now a mainstay of the Urban and Nontraditional programming effort, seeks to building strong working relationships among communities, organizations and agencies to enhance the level of balanced programming efforts available to communities.[13]

Hispanic outreach

Outreach efforts targeted to Alabama’s rapidly emerging Hispanic population are another major focus of Urban and New Nontraditional Programs.[14]

Family and Individual Well-being

Begin Education Early

The Begin Education Early program (abbreviated BEE), offered in five West Alabama counties, is designed to provide geographically isolated, limited income families with critical parenting skills to ensure that their pre-school children are prepared for the challenges of school. Paraprofessional educators work with participant families with at least one child under age 5.[15]

Expanded Food and Nutrition Education Program

In the early 1960s, five rural Alabama counties served as pilot sites for what later became known as the Expanded Food and Nutrition Education Program, a program developed to provide directed education to limited resource families to improve their eating habits and homemaking skills. From Alabama and other pilot states, the program eventually was expanded in the late 1960s to include all 50 states. While food and nutrition education always has comprised an important part of Extension education, this program, which in many states was expanded to include urban families, represented a new direction in Extension’s evolving mission.[16]

Nutrition Education

The Alabama Cooperative Extension System, both at Auburn University and Alabama A&M University, received $2 million in federal funds to provide nutrition education to food stamp recipients, who comprise approximately 11 percent of the state’s population, and to those eligible to receive food stamps. The Auburn University-headquartered Nutrition Education Program has worked exclusively with the state’s food stamp offices in 46 rural counties, while the Alabama A&M University-based Urban Nutrition Education Program has expanded outreach to new, inner-city audiences who live in public housing facilities. Another major target group includes senior sites located in metropolitan areas.[17][18]

The Marriage and Family Handbook

Beginning in 2006, Alabama Extension, in conjunction with other public and private partners, began providing copies of its Marriage and Family Handbook to probate courts in all of Alabama’s 67 counties in 2006. In a state that ranks sixth in divorce nationally, the handbook is designed to provide newlyweds with skills considered essential for healthy marriages.[19]

Community and Economic Development

Intensive Economic Development Training Course

The two-week Intensive Economic Development Training Course, originated by Alabama Extension and now operated through the Auburn University-based Economic and Community Development Institute, has graduated more than 700 economic and community development professionals throughout the state, representing a majority of those in employed in this profession in Alabama.[20]

Rural Initiative Grant Program

The Rural Alabama Initiative Grant Program, provided by Extension in partnership with the Economic and Community Development Program, provides some $500,000 worth of mini-grants, ranging from $5,000 to $20,000, to develop leadership and development programs throughout the state.[21]

Alabama 4-H Youth Development

Alabama 4-H will celebrate its centennial in 2009.

4-H Forestry and Wildlife Judging

Alabama 4-H has earned a national reputation within the past twenty years for the quality of its forestry- and wildlife-judging teams. Within the last 20 years, Alabama 4-H teams have amassed more forestry and wildlife judging national championships than any other state team in the nation.[22]

Alabama 4-H Center

Since its opening in June, 1980, the Alabama 4-H Center, located on land provided by Alabama Power Company, has expanded into a fully staffed conference center serving public and private groups throughout the state. Completion of the center’s new 4-H Environmental Science Education Center will add 17,500 square feet (1,630 m²) of additional interior space to the complex. The $7-million facility, which will be completed in 2008, is the first of its kind in the Southeast specifically designed to teach environmental issues using sustainable practices.[23][24]

Structure

In 1995, the Alabama Cooperative Extension System became the nation’s first unified Extension program, combining the resources of the 1862 and 1890 land-grant institutions. The catalyst was a landmark federal court ruling, known as Knight vs. Alabama, handed down by Judge Harold Murphy.[25] Under its terms, the Extension programs and other land-grant university functions of Alabama A&M and Auburn universities were combined, with Tuskegee University, another historically black institution with its own unique history of agricultural outreach work, serving as a cooperative partner within this unified system.

This combined effort is headed by director appointed by the presidents of Alabama A&M and Auburn universities. The Extension director serves as the organization’s chief executive officer and maintains offices at both campuses.

In written remarks outlining his rationale for the ruling, Judge Murphy also called for an expanded and updated Cooperative Extension mission that not only continued to address traditional programming needs but that also was better equipped to respond to the needs of a population that had become more urbanized and racially and ethnically diverse. In addition to providing for an associate director for Rural and Traditional Programs, who would be housed at Auburn University, Murphy also mandated that an associate director of Urban and New Nontraditional Programs be employed and housed at Alabama A&M University. This new associate director, Murphy stated, would be “expected to open new areas of Extension work and [to] expand the outreach of the Alabama Cooperative Program to more fully serve all the people of Alabama.”[26]

Directors of the Alabama Cooperative Extension System

- J. F. Duggar, 1914-1920

- Luther N. Duncan, 1920-1937

- P. O. Davis, 1937-1959

- E. T. York, 1959-1961

- Fred R. Robertson, 1961-1971

- Ralph R. Jones, 1971-1974

- W. H. Taylor (Acting), 1974-1975

- J. Michael Sprott, 1975-1983

- Ray Cavender (Acting), 1983-1984

- Ann E. Thompson, 1984-1994

- W. Gaines Smith (Interim), 1994-1997

- Stephen B. Jones, 1997-2001

- W. Gaines Smith, 2001-2007

2004 reorganization

In 2004, the Alabama Cooperative Extension System completed what was arguably the most thoroughgoing restructuring effort in its history.[1]

For decades, the bulk of Alabama Cooperative Extension programs were carried out by county agents — generalists who kept abreast of many different types of subject-matter areas and delivered a wide variety of programs. By the onset of the 21st century, a number of factors prompted Alabama Extension to reevaluate this approach. Urbanization was a key factor — a trend that not only had resulted in fewer farms but that also had drastically altered public expectations about the role Extension educators should be serving in the 21st century.

Extension administrators also cited as key factors the rapid social and technological changes reflected in a state population considerably better educated and more diverse. Throughout the 20th century, Cooperative Extension prided itself on its ability to disseminate research-based information comparatively quickly and efficiently using the prevailing technologies of the era — newspapers, radio and, more recently, television. However, following the advent of the Worldwide Web by the 1990s, Americans were becoming sophisticated information users in their own right, far better equipped to acquire information on their own.

Even so, Alabama Extension administrators still believed their organization had a critical and productive role to play in helping people make informed decisions by putting this information into context. They reasoned this could be best accomplished by specialized agents rather than the generalists who had traditionally administered Extension programming throughout the previous century.[27]

From a county to regional agent-delivered system

Following intensive study and close consultation with organizational partners and other key stakeholders, Alabama Extension transformed itself from a primarily county agent-delivered system to one in which programs increasingly will be delivered by regional agents specializing in one of the 14 different program priority areas.[1]

Regional agents

Regional Extension agents work with other agents across regional and disciplinary lines, with area and state subject-matter specialists, and with sister agencies, such as the Alabama Farmers Federation, the Alabama Forestry Commission and the Natural Resources Conservation Service, to deliver programs over a regional and, when the need arises, statewide scale.[1]

Continuing county presence

Despite the growing emphasis on regional agents, Alabama Extension, in keeping with its longstanding tradition of serving Alabamians at the grassroots, continues to operate offices in all 67 counties headed by coordinators, who work closely with regional agents and other Extension staff to deliver programs in their counties.[1]

Funding

One of the distinguishing traits associated with Cooperative Extension work throughout the country is the financial support it receives from every level of government, from the federal, state and county levels and, in an increasing number of cases, from town and city governing authorities. Like many of its sister programs throughout the country, Alabama Extension has begun looking for ways to supplement these traditional sources of funding with private support, typically in the form of grants and fees.[5]

Partnerships

Writing in the 2000 (Alabama) Extension Annual Report, then-Director Stephen B. Jones predicted an 21st century Extension System that would be “leaner, more focused and better adapted to profit from closer partnerships with other public and private players.”

While reduced federal, state and local funding have been major factors behind this greater emphasis on partnerships, Jones and subsequent Extension administrators have stressed that the value of this approach has been enhanced by the social and cultural changes that have followed the Information Age.

The Alabama Urban Community Forestry Financial Assistance Program, founded in 1999, the only such collaborative effort of its kind in the nation, often is cited as the model of how the special strengths and resources of different partnering agencies can be combined to enhance the program’s overall impact. Alabama Extension administers the program on behalf of four other partnering organizations — the U.S. Forest Service, the Alabama Forestry Commission, the Alabama Urban Forestry Association, and Auburn University’s School of Forestry and Wildlife Sciences — to develop urban forestry programs and resources in all regions of the state.

Another effort frequently cited as a partnering model is the C. Beaty Hanna Horticulture and Environmental Center. Dedicated in January 2000, the center marked a new chapter in the longstanding relationship between the Birmingham Botanical Gardens (United States) and Alabama Extension. The 30,000 square foot (3,000 m²) facility, supported by Extension, the city of Birmingham and numerous public and private donors, not only provides plant diagnostic services for the Birmingham area’s burgeoning urban horticulture industry but also serves as a major center for horticultural education.[5]

Technology

Using new technology to enhance the scope and impact of its programming has been a hallmark of Cooperative Extension work nationwide. In Alabama, Extension and its sister organization, the Experiment Station, began using emerging radio technology as early as 1922 when funds were secured to purchase a small station known as WMAV. By 1925, WAPI, “the Voice of Alabama,” a far more powerful station, was broadcasting a 1,000-watt signal from the third floor of Comer Hall on the API (now Auburn University) campus. In addition to news and weather, the station broadcast educational programs related to agriculture and homemaking.[28]

Satellite uplinking

WAPI marked the first of many ways that Alabama Extension has used cutting-edge electronic technology to extend its message to wider audiences. In the late 1980s, then-Extension Director and Auburn University Vice President for Extension Ann E. Thompson, worked with Auburn University Telecommunications and the Auburn University Athletic Department to create the Auburn University Satellite Uplink.

A statewide network also was created. Every county Extension office in the state was equipped with a satellite receiver so that each of these offices could serve as a reception site for educational programs provided from Auburn University. During breaking news events, Extension also has used the uplink to provide live interviews to television newscasts throughout the state.[29]

Alabama Extension’s Auburn University headquarters is equipped with a full-service studio and live production facility. Extension field offices have full access to live and recorded productions. The Auburn University facility also is equipped with a multimedia lab, which is equipped for video and audio Web streaming.[30]

Videoconferencing

More recently, Alabama Extension established 33 videoconferencing sites in county offices and regional centers throughout the state, affording all Alabama residents short drive times to facilities where they can view educational and certification-related programs provided via the Internet. Typically, training provided by statewide Extension subject-matter experts via videoconferencing is supplemented with instruction from county and regional experts at the reception site.[31]

Digital diagnostics

In addition to the C. Beaty Hanna Horticulture and Environmental Center, six Regional Research and Extension Centers and more than twenty-five county Extension offices throughout the state are equipped with digital diagnostic capability to provide farmers and homeowners with rapid detection of plant-borne diseases.[5]

Web site

The Alabama Cooperative Extension System Web site is accessed by more than four million visitors from across the globe each year. Alabama Extension also has been a pioneer in the use of weblogs not only as a more efficient way to educate its audiences but also to disseminate breaking news to key media gatekeepers throughout the state. To an increasing degree, these weblogs are being enhanced with streamed interviews with Extension experts.[32]

Virtual Extension

Until only a few years ago, the bulk of Extension’s outreach efforts were focused primarily on face-to-face contacts and on mass media. However, within the last decade, the advent of the Web and associated technologies has forced Alabama Extension and other state Extension programs to reassess these efforts.[33]

In his August, 2007 edition of Extension Connections, Director Gaines Smith introduced a new outreach concept known as Virtual Extension.

The concept reflects several changes that have become apparent to Extension administrators and educators within the last few years — first and foremost, that Extension’s Web presence would continue to outpace traditional sources of outreach, particularly face-to-face contact. In Smith’s view, this was not surprising, considering that clients increasingly looked to Extension’s Web presence “as the most accessible source of information about Extension-related programs and services.”

Smith also observed that as Alabama Extension’s organizational identity and online presence become more fused, the Web presence increasingly would be viewed as the major source of interaction with audiences.

While he viewed these changes as offering great opportunities, he also stressed that they hold major implications and challenges.[34]

One major effect of these changes will be on how programs are developed and carried out on behalf of Extension audiences. In the past, program-related Extension Web sites were reflections of real-world programs. Today, these roles are being reversed. To an increasing degree in the future, Extension programs will take on the identity of its Web presence.[33]

Smith also believed these changes hold major implications for how Extension educators will interact with their clients in the future. The changes taking place, he stressed, were pushing Extension educators in the direction of virtual relationship building. Educators not only should be comfortable with this new approach but also effective in building online client relationships through social networking, blogging and similar approaches.

Smith stated that that transforming Alabama Extension into a leader in this new form of outreach would be a major focus of his — and the organization’s — future efforts.[34]

History

A common perception is that the birth of Cooperative Extension followed passage of the Smith-Lever Act of 1914, which provided federal funds to land-grant universities to support Extension work. In a formal sense, this is true. Even so, the roots of Cooperative Extension extend as far back as the late 18th century, following the American Revolution, when affluent farmers first began organizing groups to sponsor educational meetings to disseminate useful farming information. In some cases, these lectures even were delivered by university professors — a practice that foreshadowed Cooperative Extension work more than a century later.[35]

These efforts became more formalized over time. By the 1850s, for example, many schools and colleges had begun holding farmer institutes — public meetings where lecturers discussed new farming insights.[36]

The Morrill Land-Grant College Act of 1862

A milestone in the history of Cooperative Extension occurred in 1862, when Congress passed and President Abraham Lincoln signed into law the Morrill Land-Grant College Act, which granted each state 30,000 acres (120 km²) of public land for each of its House and Senate members. States then could use this land as trust funds through which colleges could be endowed for the teaching of agriculture and other practical arts. [37]

The Morrill Act made possible the formation of the Agriculture and Mechanical College of Alabama (later Alabama Polytechnic Institute) in 1872, succeeding the former East Alabama Male College, a Methodist institution established in 1856. Despite being plagued initially with severe financial problems, the college, which ultimately became Auburn University, was destined to become the first headquarters of a statewide Extension program.[38]

The Second Morrill Act of 1890

In one sense, the first land-grant college act was limited. While it secured a means of establishing agricultural and mechanical colleges, it did not provide a steady source of funding to states to support these institutions. The second Morrill Act, passed in 1890, not only provided this funding but also prohibited racial discrimination by any college receiving these funds. However, so long as the federal funds were distributed "equitably," states could circumvent this anti-discrimination provision by establishing separate institutions for white and black citizens. The separate black agricultural and mechanical schools established throughout the South later became known as 1890 land-grant institutions.[39]

The Huntsville Normal School (later Alabama A&M University)

The first black school to function as an 1890 institution was the Huntsville Normal School (now Alabama A&M University) near Huntsville, established by the Alabama Legislature in 1873 and opened in 1875 with two instructors and 61 students and with an annual appropriation of $1,000. In 1891, the school, renamed the State Normal and Industrial School at Huntsville in 1878, began receiving some of the funds provided by the Second Morrill Act.[40]

Limitations of the Morrill Act

Despite the lofty visions and aspirations reflected in both Morrill Acts, the land grant university system showed signs of foundering toward the close of the 19th century. The emerging colleges faced serious challenges establishing courses of study that appealed to potential students, particularly Southerners, many of whom were dealing with the far more pressing task of reconstructing an agricultural system badly disrupted by wartime conditions. Moreover, because of the ample land available in the West, many farmers had little incentive to adopt intensive farming methods and other advanced agricultural technologies. Agricultural colleges also were criticized for not providing students with the types of training that enabled them to return to their family farms. Many land-grant college graduates were leaving farming altogether.[41]

The Hatch Experiment Station Act of 1887

Most pressing of all, many observers believed, was the glaring lack of solid agricultural research on which to base this practical teaching. Seeking to address this critical need, Congress passed the Hatch Experiment Station Act of 1887, which provided funding for agricultural experiment stations in each state.

In the opinion of many educators and policymakers, passage of this legislation represented a major stride toward improving farming. Even so, Experiment Station personnel soon discerned that scientific insights generated through research at these stations could not be fully utilized unless they were effectively communicated to farmers.

Some face-to-face contact already was provided through farmer institutes, district schools and similar efforts offered through the nation’s Experiment Stations. Even so, many Experiment Station researchers believed that these limited outreach efforts were insufficient. Many also were concerned that these efforts diverted critically needed funds away from the stations’ primary directive — conducting research.[42]

Seaman Knapp

An aging college instructor and administrator often is credited with taking a major, if not critical, lead in efforts that eventually culminated in formal Cooperative Extension work. In the view of some, he rightly deserves the title of “father” of the Extension Service. [43]

Seaman Ashael Knapp (1831-1911) was a Union College graduate, Phi Beta Kappa member, physician, college instructor, and, later, administrator, who took up farming late in life, moving to Iowa to raise general crops and livestock.

The first seeds of what would later become an abiding interest in farm demonstration were planted after he became active in an organization called “The Teachers of Agriculture,” attending their meetings at the Michigan Agricultural College in 1881 and the Iowa Agricultural College in 1882. Knapp was so impressed with this teaching method that he drafted a bill for the establishment of experimental research stations, which later was introduced to the 47th Congress, laying the foundation for a nationwide network of agricultural experiment stations.

Knapp later served as president of Iowa Agricultural College, but his interest in agricultural demonstration work did not occur until 1886, when he moved to Louisiana and began developing a large tract of agricultural land in the western part of this state.

Knapp neither could persuade local farmers to adopt the techniques he had perfected on his farm, nor could he enlist farmers from the North to move to the region to serve collectively as a sort of educational catalyst. What he could do, he reasoned, was to provide incentives for farmers to settle in each township with the proviso that each, in turn, would demonstrate to other farmers what could be done by adopting his improved farming methods.

The concept worked. Northern farmers began moving into the region, and native farmers began buying in to Knapp’s methods.

By 1902, Knapp was employed by the government to promote good agricultural practices in the South.

Based on his own experience, Knapp was convinced that demonstrations carried out by farmers themselves were the most effective way to disseminate good farming methods. His efforts were aided by the onslaught of the boll weevil, a voracious cotton pest whose presence was felt not only in Louisiana but also throughout much of the South. Damage associated with this pest instilled fear among many merchants and growers that the cotton economy disintegrating around them.

In the view of many, a farm demonstration at the Walter G. Porter farm in Terrell, Texas, set up by the Department of Agriculture at the urging of concerned merchants and growers, was the first in a series of steps that eventually lead to passage of the federal legislation that formalized Cooperative Extension work.

USDA officials were so impressed with the success of this demonstration that they appropriated $250,000 to combat the weevil — a measure that also involved the hiring of farm demonstration agents. By 1904, some 20 agents were employed in Texas, Louisiana and Arkansas. The movement also appeared to be spreading to neighboring Mississippi and Alabama. [44]

Tuskegee Institute

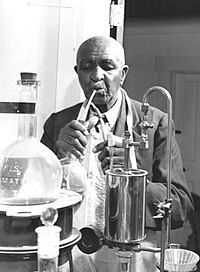

Tuskegee Institute (now known as Tuskegee University), a black, largely privately funded school, laid much of the foundation for what ultimately would become Cooperative Extension work. Much of the credit for these pioneering efforts can be attributed directly to Booker T. Washington, founder of the institute, and to world renowned agricultural researcher George Washington Carver.

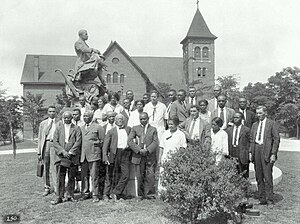

The first annual Tuskegee Farmer Conference, begun at the prompting of Washington in 1892, initially attracted some 500 participants. Still held annually, the conference is regarded not only as the cornerstone of black agricultural outreach work but as a major milestone in the development of Cooperative Extension work in general

Nevertheless, much like their counterparts at nearby API and in other and other land-grant institutions, Washington and Carver understood that the insights generated at Tuskegee and other agricultural research facilities throughout the nation could not be fully utilized unless they were successfully imparted to farmers.[45]

Jesup wagons

With this in mind, Tuskegee pioneered the use of agricultural demonstration wagons (commonly known as Jesup wagons in honor Morris Jesup, the New York banker and philanthropist who underwrote the cost for their fitting and equipment) to instruct farmers and sharecroppers in far-flung regions of the state about efficient farming methods. Carver not only drafted the plans for the wagons but also selected the equipment, drew instructional charts and suggested lecture topics to be delivered at each visit.

The wagons were so successful that they eventually were adopted as an integral part of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s outreach program.[46]

Thomas Monroe Campbell, of Tuskegee Institute, was appointed the nation’s first black extension agent in 1906 and assigned to operate the Jesup wagons under Carver’s oversight. By 1925, African American (known at the time as Negro) Extension work encompassed 31 agents working in 21 Alabama counties.[47]

Alabama Polytechnic Institute

API also had gone a long way toward laying the groundwork for Cooperative Extension work in the state. Even before passage of the Smith-Lever Act, Luther Duncan, a 1900 API graduate, through his work with the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Bureau of Plant Industries, had organized numerous Boys’ Corn Clubs throughout the state totaling more than 10,000 members.[48]

Corn and Tomato Clubs

These Corn Clubs, forerunners of 4-H clubs, marked another major step toward the formalization of Cooperation Extension work. Ostensibly organized to teach farm boys advanced agricultural methods, the clubs served a dual purpose.[49] Duncan and other professional agricultural workers throughout the nation who organized these clubs reasoned that children often were more receptive to technological change than their parents. In time, fathers adopted these techniques themselves after observing their sons’ successes. Similar successes were noted with girls’ tomato clubs — an outreach technique closely patterned after the corn clubs — as mothers began adopting canning and other food preservation techniques imparted to their daughters.[50]

By 1910, there were 37 agents at work in 41 Alabama counties, though operating under the USDA. Even so, the salaries of many of these employees were supplemented by county funding — a practice that would distinguish formal Cooperative Extension work for the next century..[51]

Passage of the Smith-Lever Act of 1914

In 1914, the long awaited Smith-Lever Act, which has been regarded as “one of the most striking educational measures ever adopted by any government,” finally was passed. The act provided for state matching of federal funds to establish a network of county farm educators in every state in the nation. The agreement with the states drafted shortly after passage of the act stipulated that not only Smith-Lever-related Extension work but all Extension-related work associated with the U.S. Department of Agriculture in a state would be carried out through the state college of agriculture. Likewise, each state college was expected to establish a separate Extension division with a leader responsible for administering state and federal funds.[52]

Alabama formally accepted the provisions of the Smith-Lever Act in 1915, organizing the Alabama Extension Service under the direction of the Alabama Polytechnic Institute in Auburn. J.F. Duggar, a long-serving API administrator, assumed the reins of the new organization, while Duncan was appointed superintendent of Junior and Home Economics Extension in cooperation with the USDA. These two units operated independently until Duncan was named head of the Alabama Extension Service in 1920.[53]

Under the Smith-Lever Act, administrative oversight of Tuskegee’s Extension program came under the direction of Duggar in 1915, though in a de facto sense, the program remained autonomous and under the direction of African-Americans.[54]

Despite its pioneering efforts in extension work, Tuskegee was not eligible to receive 1890 funds until 1972.[55]

Initial focus

The Alabama Extension Service initially focused on improving the bleak economic prospects of Alabama farmers, most of whom raised cotton under the persistent threat of the boll weevil, a voracious and highly destructive cotton pest. As funds permitted, home demonstration agents also were employed to provide farm wives with practical assistance with food preservation and other home-related improvements.

Eventually, program areas were expanded to include assistance with dairying, livestock production, agronomy, horticulture, farm marketing and plant and animal diseases. Youth outreach, typically in the form of Boys and Girls Clubs, also comprised an integral part of Extension work.[56]

In 1914, forty-three of Alabama’s 67 counties were served by agents. By the 1920s, Extension agents, many of whom were college graduates, were operating out of fully staffed and equipped offices in many counties. Enhanced federal and state funding also enabled the Extension Service to hire 11 full-time and part-time subject-matter specialists to provide agents with guidance and assistance with program delivery.[57] The basic contours of the system were in place. From this comparatively modest beginning, Alabama Extension eventually built a statewide presence with fully staffed and equipped offices in all 67 counties.

Historical Panorama of Alabama Agriculture

As part of its commemoration of Auburn University’s Sesquicentennial in 2006, the Alabama Cooperative Extension System reintroduced a series of agriculture-related murals it commissioned for display at the 1939 Alabama State Fair. Known as the Historical Panorama of Alabama Agriculture, the murals depict key events of Alabama agricultural history.

They were designed every bit as much for their educational as aestheic value. Setting out the purpose for the murals, then-Alabama Extension Director P. O. Davis noted that “agriculture in Alabama, and in this nation, is in a period of change — a change toward improvement and progress.” Alabama, Davis stressed, was diversifying, moving from a primarily cotton-based economy “into a combination of cotton and other cash crops plus livestock and poultry.” He envisioned a dual purpose for the murals and supporting exhibits: to celebrate Alabama’s rich agricultural history but also to focus farmers on a “vision of the future.” [58]

Painted by Mobile native John Augustus Walker, one of Alabama’s premiere artists of the era, these murals are among Alabama Extension’s most prized artifacts and reflect one of the most significant chapters in the state’s agricultural history. They also are considered prime examples of Works Progress Administration-related art associated with the Great Depression era.[59]

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f "2004 Highlights," Alabama Cooperative Extension System.

- ^ a b c "2003 Annual Report," Alabama Cooperative Extension System

- ^ Henderson, Chinella "Urban Centers," Metro News, Alabama Cooperative Extension System.

- ^ Yeager, Joseph and Stevenson, Gene, "Inside Ag Hill: The People and Events That Shaped Auburn's Agricultural History from 1872 through 1999", Chelsea, Michigan: Sheridan Books, 1999, p.21

- ^ a b c d "Taking the University to the People: 2000 Annual Report," Alabama Cooperative Extension System

- ^ a b "How Extension Works for You," Alabama Cooperative Extension System.

- ^ "Extension Program Training Young Producers to Become Public Leaders," Alabama Cooperative Extension System.

- ^ "Alabama Beef Quality Assurance: Getting Started," ANR-1277, Alabama Cooperative Extension System

- ^ "Alabama Master Gardeners Program," Alabama Cooperative Extension System

- ^ a b "Your Experts for Life," 2002 Annual Report, Alabama Cooperative Extension System.

- ^ "Auburn Researchers and Extension Specialist Build Field of Dreams," News and Public Affairs, Extension Communications, Alabama Cooperative Extension System, Aug. 26, 2003.

- ^ "Urban Affairs and New Nontraditional Programs," MetroNews, Alabama Cooperative Extension System, October-December, 2001.

- ^ "Cooperative Extension Hosts Urban-Rural Interface Conference," News and Public Affairs, Extension Communications, Alabama Cooperative Extension System, March 8, 2002.

- ^ "Extension's Outreach to Alabama's Growing Hispanic Communities," 2003 Impact Statements, Alabama Cooperative Extension System.

- ^ "Alabama's BEE Program - Enhancing School Readiness in Underserved Programs," 2003 Impact Statements, Alabama Cooperative Extension System.

- ^ "Alabama Expanded Food and Nutrition Education Program: Celebrating 40 Years of Success," Alabama Cooperative Extension System.

- ^ "Nutrition Education Program," Alabama Cooperative Extension System.

- ^ "Urban Nutrition Education Program," Alabama Cooperative Extension System.

- ^ "Alabama Marriage Handbook: Keys to a Healthy Marriage," HE-0829, Alabama Cooperative Extension System.

- ^ "Community and Economic Development," Extension Update, Alabama Cooperative Extension System, Fall, 2005.

- ^ "Rural Initiative Grant Program," Action: Public Information for Alabama Citizens, Alabama Cooperative Extension System, Spring, 2007.

- ^ "Seven and Still Counting," 2002 Annual Report, Alabama Cooperative Extension System.

- ^ "4-H Center," Alabama Cooperative Extension System.

- ^ "New Rooms and Environmental Center," 4-H Center, Alabama Cooperative Extension System.

- ^ "Judge ends desegregation case," Decatur Daily, Dec. 14, 2006.

- ^ "The Unification of the Alabama Land-Grant System: Unification of the Alabama Cooperative Extension System and the Creation of an Associate Director of Urban Affairs and New Nontraditional Programs", Hon. Harold L. Murphy, US District Court, Northern District of Georgia.

- ^ "Alabama Extension being reorganized," Southeast Farm Press, Aug. 4, 2004.

- ^ Yeager and Stevenson, p. 91.

- ^ Yeager and Stevenson, p. 378.

- ^ "How Extension Video and Satellite Technology Works for You", EX-49, Alabama Cooperative Extension System, December, 2004.

- ^ "Technology for Expanded Program Delivery," 2006 Highlights, 2006 Extension Highlights, EX-0036-I, Alabama Cooperative Extension System.

- ^ "A World of Alabama Extension Sources," 2006 Highlights, 2006 Extension Highlights, EX-0036-I, Alabama Cooperative Extension System.

- ^ a b Ray, Chales D., "The Virtual Extension Specialist," Journal of Extension, April, 2007. Cite error: The named reference "The Virtual Extension Specialist" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b "Extension Connections: The Official Letter of the Alabama Cooperative Extension System," August, 2007.

- ^ Rasmussen, Wayne D., Taking the University to the People: Seventy-five Years of Cooperative Extension, Ames, Iowa: Iowa State University Press, 1989, p. 18.

- ^ Rasmussen, p. 28.

- ^ Rasmussen, p.23.

- ^ "Auburn University History:The Presidency of Isaac Taylor Tichenor, 1872-1882," Auburn University Libraries, Auburn University

- ^ Rasmussen, p. 18.

- ^ "Alabama A&M University: Historical Sketch," History, Alabama A&M University.

- ^ Rasmussen, p. 25.

- ^ Rasmussen, pp. 26-28.

- ^ Rasmussen, p. 34.

- ^ Smith, Jack D., "Information and Inspiration: An Early History of the Alabama Cooperative Extension System," Unpublished Manuscript, March, 29, 1989. pp. 13-16.

- ^ Yeager and Stevenson, p. 82.

- ^ [http://acswebcontent.acs.org/landmarks/landmarks/carver/chemist.html "Agricultural Chemist ( George Washington Carver)", National Historic Chemical Landmarks, American Chemical Society.]

- ^ "Helping People Help Themselves," Cooperative Extension, Tuskegee University

- ^ Yeager and Stevenson, p. 80.

- ^ Yeager and Stevenson, p. 84.

- ^ Yeager and Stevenson, p. 95.

- ^ Yeager and Stevenson, p. 84.

- ^ Rasmussen, p. 50.

- ^ Yeager and Stevenson, p.79.

- ^ Yeager and Stevenson, p. 81.

- ^ Rasmussen, p. 24.

- ^ Yeager and Stevenson, p. 87.

- ^ Yeager and Stevenson, p. 85.

- ^ Whatley, Carol, "Depression-era Murals of Alabama Agriculture to be Displayed at Auburn University's Foy Union, Sept. 21," Auburn University Sesquicentennial, Office of Communications and Marketing, Auburn University, Sept., 2006.

- ^ "John Augustus Walker", A Presentation of the Alabama Cooperative Extension System, Auburn University Sesquicentennial.

External links

- Alabama Cooperative Extension System

- Alabama A&M University

- Auburn University

- Tuskegee University

- U.S. Department of Agriculture

- Cooperative State, Research, Education and Extension Service

See also

- Cooperative Extension Service

- Luther Duncan

- List of land-grant universities

- National Association of State Universities and Land-Grant Colleges

- State university

- Agricultural extension

- Historical Panorama of Alabama Agriculture