South Slavic languages

This article needs attention from an expert in Linguistics. Please add a reason or a talk parameter to this template to explain the issue with the article. |

| South Slavic | |

|---|---|

| Geographic distribution | Eastern Europe |

| Linguistic classification | Indo-European

|

| Subdivisions |

|

| Language codes | |

| – | |

| |

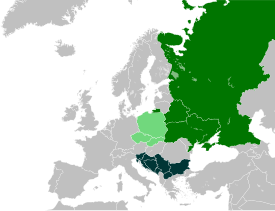

| South Slavic languages and dialects |

|---|

South Slavic languages comprise one of the three geographical groups of Slavic languages (besides West and East Slavic). There are around 30 million speakers of these languages, mainly in the Balkans. The South Slavic languages are further subdivided into Eastern and Western subgroups.

German, Hungarian and Romanian generally form a belt which geographically separate speakers of South Slavic languages from their counterpart West and East Slavic language speakers.

The first South Slavic language to be written was Old Church Slavonic in the 9th century, which was based on the local dialect in the Thessalonica region. It is retained as a liturgical language in some South Slavic Orthodox churches.

Classification

Slavic languages belong to Balto-Slavic family, which itself belongs to of the Indo-European language family. The South Slavic family itself exists strictly as a geographical grouping, not forming a genetic node in Slavic language family - there was never a period in which all South Slavic dialects exhibited exclusive set of extensive phonological, morphological and lexical changes peculiar to them and them only. The was never a period of cultural of political unity in which "Proto-South-Slavic" could have existed, in which Common South Slavic innovations could have occurred. Several South-Slavic-only lexical and morphological patterns that have been proposed have all been proven to be Common Slavic archaisms, or are shared with some Slovakian or Ukrainian dialects.

Within South Slavic, however, there could have been Proto-West-South-Slavic (ancestral to dialects of Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia, Serbia, Montenegro and Slavic dialects of Kosovo) and Proto-East-South-Slavic (ancestral to Bulgaro-Macedonian dialects). Older literature also frequently makes a notion of "Serbo-Croatian" or "Central-South-Slavic" dialect continuum or diasystem which would in theory compromise Čakavian, Kajakvian, Štokavian and sometimes Torlakian dialects. Čakavian, Kajkavian and Torlakian dialects have over the centuries exhibited extensive lexical and, to a lesser degree, morphological influences (such as transitional ščakavian mixture) from dominant Štokavian, which has lead many into false assumption of some common ancestral dialect, or of exclusve set of isoglosses which would connect them all, but very important thing to note is that there was never a language ancestral to idioms spoken nowadays by Bosniaks, Croats, Monenegrins and Serbs. "Serbo-Croatian dialect system" or its much less common but politically more correct alternative "Central South Slavic diasystem" exists only as an arbitrary geographical grouping, nowadays largely obsoleted as a term due to the break-up of Yugoslavia and the advent of newly-established republics.

All South Slavic dialects form a dialectal continuum stretching from today's southern Austria to southeast Bulgaria. On the level of dialectology or linguistic typology, several major dialects can be distinguished, but their borders are blurred due to strong contact and frequent migrations in the past. On the other hand, cultural establishment and national liberation from occupying Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian Empires, followed by formation of nation-states in 19th and 20th century, caused development and codification of standard national languages. These processes have (almost) ended just at the end of 20th century, with the breakup of Yugoslavia (with only the Montenegrin national and linguistic issue left to be resolved). Most of those languages selected one dialect as the basis of a literary language and, as a result, some dialects got deprecated and marginalized, while others flourished. Further, the national and ethnic borders do not coincide with dialectal boundaries in most cases.

Thus, two distinct classifications of South Slavic languages can be drawn; one from a geographic point of view, and the other from a sociolinguistic point of view. The two classifications seldom map 1:1. For example, Croats speak three main and two exclaval dialects in four countries, while their standard language is based on Ijekavian Neo-Štokavian.

Note: Due to different political statuses of languages/dialects and different historical contexts, the classifications are necessarily arbitrary to some extent.

Dialectal classification

- South Slavic languages

- Eastern

- Transitional

- Western

- Štokavian dialect

- Šumadija-Vojvodina subdialect (Ekavian) in Serbia

- Smederevo-Vršac subdialect (Ekavian) in Serbia

- Kosovo-Resava subdialect (Ekavian) in Serbia

- Prizren-South Morava subdialect (Ekavian) in Serbia

- Svrljig-Zaplanje subdialect (Ekavian) in Serbia

- Timok-Lužnica subdialect (Ekavian) in Serbia

- Herzegovina subdialect in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, and Montenegro

- Ijekavian subdialect in Croatia (Bosnia and Herzegovina)

- Ikavian subdialect in Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Serbia

- Gradišče dialect (in Austria, and Hungary)

- Molise Croatian dialect (in Italy)

- Caraşova dialect (in Romania)

- Bunjevac dialect (in Serbia)

- Čakavian Croatian dialect

- Burgenland Croatian (in Austria, and Hungary)

- Buzet subdialect in Croatia

- Southwestern Istrian subdialect in Istria

- North Čakavian subdialect in Croatia and Istria

- South Čakavian subdialect in Dalmatia

- Lastovo subdialect in Dalmatia

- Kajkavian Croatian dialect

- Zagora-Međimurje in Croatia sub-dialect

- Križevci-Podravina subdialect in Croatia

- Turopolje-Posavina subdialect in Slavonia

- Prigorski subdialect in Croatia

- Donja Sutla subdialect in Croatia

- Goranski subdialect in Croatia

- Slovene language

- Štokavian dialect

Sociolinguistic classification

South Slavic languages

- Eastern

- Western

- Serbian language

- Standard - Štokavian:

- Vojvodina-Šumadija sub-dialect (standard for Serbia)

- East Herzegovinian sub-dialect (standard for Bosnian Serbs and Montenegrins)

- Montenegrin, a term used for the language of Montenegro

- Non-standard - Torlakian

- Standard - Štokavian:

- Bosnian language (east Bosnian dialect - standard)

- Croatian standard language (standard Shtokavian-iyekavian)

- Čakavian Croatian dialect (non-standard)

- Kajkavian Croatian dialect (non-standard)

- Molise Croatian dialect

- Burgenland Croatian dialect

- Bunjevac dialect

- Carasova Croatian dialect

- Slovene language

- Serbian language

Eastern group of South Slavic languages

Bulgarian dialects

Macedonian dialects

- see also:Dialects of Macedonian language

Transitional South Slavic languages

Torlakian dialect

There also exists another dialect, called torlački or Torlak, which is spoken in southern and eastern Serbia, northern Republic of Macedonia and western Bulgaria, and often considered transitional between Central and Eastern group of South Slavic languages.

It is even thought to fit into the so-called Balkan sprachbund, an area of linguistic convergence among languages due to long-term contact rather than being genetically related.

Central or Eastern Western group of South Slavic languages

History

Each of these primary and secondary dialectical units breaks down into subdialects and accentological isoglosses by region. In the past (and now in mountains and islands), it was not uncommon for individual villages to have some of their own words and phrases. However, throughout the twentieth century the various dialects have been strongly influenced by the Štokavian standards through mass media and public education, and much of the "local color" has been lost chiefly in towns.

With the breakup of Yugoslavia, rise of national awareness has also caused many to modify their speech according to newly established standard language guidelines. The various wars have also caused mass migrations, and changed the ethnic and thus dialectal picture of some areas, especially in Bosnia and Herzegovina, but also in central Croatia and in Serbia (especially in Vojvodina). In some areas it is unclear whether location or ethnicity is now the dominant factor in the dialect of the speaker.

Because of these forces, the speech patterns of some communities and regions are in a state of flux, and it is difficult to determine which dialects will die out entirely. Further research over the next few decades will be necessary to determine the changes made in the dialectical distribution of the language.

Dialect to language name mapping

The table below shows the relationship between the dialects of so-called Central South Slavic diasystem and the names their native speakers might call them.

| Dialect | Sub-Dialect | Serbian | Croatian | Bosnian | Montenegrin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Štokavian | Torlakian dialect | x | |||

| Zeta-South Sandžak | x | x | |||

| Eastern Herzgovinian | x | x | x | x | |

| Šumadija-Vojvodina | x | ||||

| Western Ikavian | x | ||||

| Kosovo-Resava | x | ||||

| Eastern Bosnian | x | ||||

| Slavonian | x | ||||

| Čakavian | x | ||||

| Kajkavian | x |

Štokavian dialects and languages

Molise Croatian

The Molise Croatian (or Molise Slavic) dialect is spoken in three villages of the Italian region of Molise, by the descendants of South Slavs who migrated there from the eastern Adriatic coast in the 15th century. Because these people have migrated away from the rest of their kinsmen so long ago, their diaspora language is rather distinct from the standard language, and rather influenced by Italian. However, their speech retains some archaic features that were lost in all the other Štokavian dialects after the 15th century, and thus makes it a valuable tool in accentological research.

Dialects and official languages

Bosnian, Croatian, Montenegrin and Serbian languages, both as sets of dialects and as codified standard languages:

- Serbian language is a system of two dialects: Štokavian and Torlakian.

- Bosnian language is dialects: Štokavian East Bosnian dialects.

- Montenegrin language is dialects: Štokavian Montenegrin dialects (Zetski).

- Croatian language is a system of three dialects: Čakavian, Štokavian and Kajkavian.

Čakavian dialects and languages

Čakavian dialects

Chakavian (Čakavian) is spoken in the western, central, and southern parts of Croatia, mainly in Istria, Kvarner Gulf, Dalmatia, and also in Croatian inlands (Gacka, Pokupje etc.). The Čakavian renders Proto-Slavic yat mostly as i or also as e (rarely as (i)je), or even mixed Ekavian-Ikavian. Many dialects of Čakavian preserved significant number of Dalmatian words, but also have a lot of loan words from Venetian, Italian, Greek and other Mediterranean languages.

Example: Ča je, je, tako je vavik bilo, ča će bit, će bit, a nekako će već bit!

Burgenland Croatian

This dialect is spoken primarily in the federal state of Burgenland in Austria, but also in nearby areas in Vienna, Slovakia, and Hungary by descendants of Croats who migrated there in the 16th century. This dialect or possibly family of dialects is quite different from standard Croatian. It has been heavily influenced by German and also Hungarian. In addition, it has some properties from all three of the major dialectical groups in Croatia, as the migrants did not all come from the same areas of Croatia. The "micro-literary" standard is based on a Čakavian dialect, and, like all Čakavian dialects, is characterized by very conservative grammatical structures: it preserves, prominently, case endings lost in the Štokavian base of standard Serbo-Croatian.

At most 100,000 people speak Burgenland Croatian and almost all are bilingual in German. Its future is uncertain, but there is some movement to preserve it. It has official status in six districts of Burgenland, and is used in some schools in Burgenland and neighboring western parts of Hungary.

Western group of South Slavic languages

Kajkavian dialects

Kaykavian is mostly spoken in northern and northwest Croatia including 1/3 of country near the Hungarian and Slovenian borders: chiefly in and around towns Zagreb, Varaždin, Čakovec, Koprivnica, Petrinja, Delnice, etc. It renders yat mostly as e (rarely as diphthongal ie); note that this pronouncing cannot be equated to that of the Ekavian-Shtokavian dialects, as many kaykavian dialects distinguish a closed e nearly ae (from yat) and an open e (from original e).

It almost lacks several palatals (ć, lj, nj, dž) found in Shtokavian dialect, and has some loanwords from the nearby Slovene dialects, as well as from German chiefly in towns.

Example: Kak je, tak je; tak je navek bilo, kak bu tak bu, a bu vre nekak kak bu!

Slovene language

Grammar

Eastern-Western division

In the broadest terms, the Eastern dialects of South Slavic (ie. Bulgarian and Macedonian dialects) most differ from the Western dialects in the following ways :

- The Eastern dialects have almost completely lost their noun declensions, and have become entirely analytic.[2];

- The Eastern dialects have developed definite article suffixes in similar fashion to the other languages in the Balkan Sprachbund.[3]

- The Eastern dialects have completely lost the infinitive. Thus, the first person singular is considered the main part of a verb. Sentences that in other languages would require an infinitive are constructed through a clause – eg. Bulgarian - искам да ходя (iskam da hodya) - "I want to go" (lit. "I want that I go").

Aside from these three main areas, there are several smaller, but still significant differences:

- The Western dialects have three genders in both the singular and plural (and Slovenian even has dual, see below), while the Eastern dialects only have them in the singular, eg. Serbian - on (he), ona (she), ono (it), oni (they, masc), one (they, fem), ona (they, neut); in Bulgarian, te (they) covers the whole plural.

- Inheriting a generalization of another demonstrative as a base form for 3rd person pronoun that already occurred in Late Proto-Slavic, standard literary Bulgarian, just like Old Church Slavonic, does not use Slavic "on-/ov-" as base forms, such as on, ona, ono, oni (he, she, it, they), and ovaj, ovde (this, here), but uses instead "to-/t-"based pronouns, such as toy, tya, to, te, and tozi, tuk (it only retains onzi - "that" and its derivatives); Western Bulgarian dialects and Macedonian do have some "ov-/on-" pronouns, and sometimes use them interchangeably.

- All dialects of the Central South Slavic area contain the concept of "any" - eg. Serbian neko "someone"; niko "no one"; iko "anyone". All others lack the last, and make do with some- or no- constructions instead. [4]

Division within Western dialects

- While Serbian, Bosnian and Croatian Shtokavian dialects have basically the same grammar, its usage is very diverse. While all three languages are relatively highly inflected, the further east one goes, the more likely it is that analytic forms are used - if not spoken, at least in the written language. A very basic example is :

- Croatian - hoću ići - "I want - to go"

- Serbian - hoću da idem - "I want - that - I go"

- Slovenian has retained Proto-Slavic dual number (which means that it has nine personal pronouns in the third person) for both nouns and verbs, eg. –

- nouns: volk (wolf) → volkova (two wolves) → volkovi (some wolves)

- verbs: hodim (I walk) → hodiva (the two of us walk) → hodimo (we walk)

Division within Eastern dialects

- In Macedonian, the perfect tense is largely based on the verb "to have", as in other Balkan languages like Greek and Albanian (like in English), as opposed to the verb "to be", which is used as the auxiliary in all other Slavic languages (see also here) - eg.

- Macedonian - imam videno - I have seen (imam - "to have")

- Bulgarian - vidyal sum - I have seen (sum - "to be")

Writing

The languages to the West of Serbian use the Roman alphabet, while those to the East and South use Cyrillic. Serbian itself constitutionally uses the Cyrillic script, though commonly, it is the Roman alphabet which is in greater use. For example, most newspapers are written in Cyrillic, while most magazines - in Roman script; books written by Serbian authors are written in Cyrillic, while books translated from foreign authors are usually in Roman script; on television, any writing as part of a television programme is usually in Cyrillic, while adverts are usually in Western script.

The division is traditionally partly based on religion – Serbia, Montenegro, Bulgaria and Macedonia, which use Cyrillic, are Orthodox countries, while Croatia and Slovenia, which use Roman script, are Catholic;[5] the Bosnian language, used by the Muslim Bosniaks, also uses the Roman script.

The Glagolitic alphabet was also used in the Middle Ages, most notably in Bulgaria and Croatia, but gradually disappeared.

Notes

- ^ Torlakian can be treated as the part of both the Eastern South Slavic group and the Western. Speakers generally identify as ethnic Serbs, Bulgarians and Macedonians depending on their country of origin. Most Torlakian dialects are spoken in Serbia, and thus considered Serbian.

- ^ Note that some remnants of cases do still exist in Bulgarian, such as:

- the numerical plural in the masculine and the incomplete definite article suffix are actually remnants of the old genitive, hence why they are invariably identical to each other:

- stol - "chair" (sing.) → stolove - "chairs" (plur.) → dva stola - "two chairs" (numerical plural/old genitive)

- stol - "chair" (indefinite) → "stolat - "the chair" (definite, subject) → pod stola - "under the chair" (definite, object/old genitive)

- the vocative -

- for family members - eg. майка → майко (maika → maiko - "mother")

- for masculine names - eg. Перър → Петре (Petar -> Petre);

- set phrases, such as nosht ("nght") → noshtem ("during the night"); sbogom ("farewell" - lit. "s + bog + ending" - "with god")

- the numerical plural in the masculine and the incomplete definite article suffix are actually remnants of the old genitive, hence why they are invariably identical to each other:

- ^ In Macedonian, these are especially well-developed, also taking on a role similar to demonstrative pronouns:

- Bulgarian : stol - "chair" → stolat - "the chair"

- Macedonian : stol - chair → stolot - "the chair" → stolov - "this chair here" → stolon - "that chair there"

- note that Macedonian also has separate demonstratives - eg. ovoj stol - "this chair"; onoj stol - "that chair".

- ^ In Bulgarian, more complex constructions such as "koyto i da bilo" ("whoever it may be" ≈ "anyone") can be used if the distinction is absolutely necessary.

- ^ This distinction is true for the whole Slavic world: the Orthodox Russia, Ukraine and Belarus also use Cyrillic, as does Rusyn (Eastern Orthodox/Eastern Catholic), while the Catholic Poland, Czech Republic and Slovakia use Roman script, as does Sorbian. Romania and Moldova, which are not Slavic but are Orthodox, also used Cyrillic until 1860 and 1989, respectively, and it is still used in Transdnistria.

References

- Ranko Matasović (2008). Poredbenopovijesna gramatika hrvatskoga jezika (in Croatian). Zagreb: Matica hrvatska. ISBN 978-953-150-840-7.

See also

External links

- Burgenland Croat Center (in English, German and Croatian)