Celtic nations

Celtic nations is a term used to describe territories in North-West Europe in which that area's own Celtic languages and cultural traits have survived. The term "nation" is used in this context to mean a group of people associated with a territory and who share a common identity, language or culture. It is not synonymous with "sovereign state", but rather with traditional territory's or "countries".

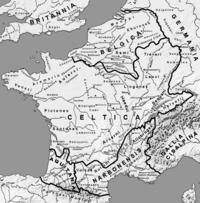

The six territories recognised as Celtic nations are Brittany (Breizh), Cornwall (Kernow), Ireland (Éire), Isle of Man (Mannin), Scotland (Alba), and Wales (Cymru).[1][2] Limitation to these six is sometimes disputed by people from Asturias and Galicia.[3][4][5] Until the expansions of the Roman Republic and Germanic tribes, a large part of Europe was mainly Celtic.[6]

Terminology

The term "Celtic nations" derives from the linguistics studies of the 16th century scholar George Buchanan and the polymath Edward Lhuyd.[1] As Assistant Keeper and then Keeper of the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford (1691–1709), Lhuyd travelled extensively in Great Britain, Ireland and Brittany in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. Noting the similarity between the languages of Brittany, Cornwall and Wales, which he called "P-Celtic" or Brythonic, the languages of Ireland, the Isle of Mann and Scotland, which he called "Q-Celtic" or Goidelic, and between the two groups, Lhuyd published Archaeologia Britannica: an Account of the Languages, Histories and Customs of Great Britain, from Travels through Wales, Cornwall, Bas-Bretagne, Ireland and Scotland in 1707. His Archaeologia Britannica concluded that all six languages derived from the same root. Lhuyd theorised that the root language descended from the languages spoken by the Iron Age tribes of Gaul, whom Greek and Roman writers called Celtic.[7] Having defined the languages of those areas as Celtic, the people living in them and speaking those languages became known as Celtic too. There is some dispute as to whether Lhuyd's theory is correct. Nevertheless, the term "Celtic" to describe the languages and peoples of Brittany, Cornwall and Wales, Ireland, the Isle of Mann and Scotland was accepted from the 18th century and is widely used today.[1]

These areas of Europe are sometimes referred to as the "Celt belt" or "Celtic fringe" because of their location generally on the western edges of the continent, and of the states they inhabit (e.g. Brittany is in the northwest of France, Cornwall is in the south west of Great Britain, Wales in western Great Britain and the Gaelic-speaking parts of Ireland and Scotland are in the west of those countries).[8][9] Additionally, this region is known as the "Celtic Crescent" because of the near crescent shaped position of the nations in Europe.[10]

Festival Interceltique de Lorient

Formal cooperation between the Celtic nations is active in many contexts, including politics, languages, culture, music and sports:

The Celtic League is an inter-Celtic political organisation, which campaigns for the political, language, cultural and social rights, affecting one or more of the Celtic nations.[11]

Established in 1917, the Celtic Congress is a non-political organisation that seeks to promote Celtic culture and languages and to maintain intellectual contact and close cooperation between Celtic peoples.[12]

Festivals celebrating the culture of the Celtic nations include the Festival Interceltique de Lorient (Brittany), the Pan Celtic Festival (Ireland), the National Celtic Festival (Portarlington, Australia) and the Celtic Media Festival (showcasing film and television from the Celtic nations).[5][13][14][15]

Inter-Celtic music festivals include Celtic Connections (Glasgow), and the Hebridean Celtic Festival (Stornoway).[16][17]

Competitions are held between the Celtic nations in sports such as rugby (Magners League – formerly known as the Celtic League) and athletics (Celtic Cup).[18][19]

Acknowledgement of their Celtic history led to the period of rapid economic growth in Ireland between 1995–2007 (and to the country itself) to become known as the Celtic Tiger.[20][21] Aspirations for Scotland to achieve a similar economic performance to that of Ireland's led the Scotland First Minister Alex Salmond to set out his vision of a Celtic Lion economy for Scotland, in 2007.[22]

Linguistics

Each of the six nations has its own living Celtic language. Ireland, Wales, Brittany and Scotland contain areas where a Celtic language is used on a daily basis – in Ireland the area is called a Gaeltacht, in Wales Y Fro Gymraeg and in Brittany Breizh-Izel.[23] Generally these communities are in the west of their countries and in upland or island areas. In Wales, the Welsh language is a core curriculum (compulsory) subject, which all pupils study.[24] Additionally, 20% of school children in Wales go to Welsh medium schools, where "they are taught entirely in the Welsh language".[25] In Ireland, 7.4% of primary school education is through Irish medium education.[25]

In Scotland, the term Gàidhealtachd historically also distinguished the Gaelic-speaking Highland areas north of the Central Belt and east of the east coast from the Scots-speaking Lowlands. However, in modern Gaelic this term has come to denote the Highland region (minus the Western Isles) and no longer denotes a Gaelic-speaking area. Instead, terms such as sgìre Ghàidhlig "Gaelic area" are used.

| Nation | Celtic name | Language | People | Population | Native-competent speakers | Percentage of population |

| Ireland | Éire | Irish (Gaeilge) |

Irish (Éireannaigh) |

6,000,000 | Republic: 355,000 (native) 1,660,000 (competent)[26] Northern: 10.4% (see note [27]) |

Republic: 42%[26] Northern: 10.4% (see note [27]) |

| Cymru | Welsh (Cymraeg) |

Welsh (Cymry) |

3,000,000 | 611,000[28] | 20.8%[29] | |

| Breizh | Breton (Brezhoneg) |

Bretons (Breizhiz) |

4,000,000 | 200,000[30] | 3%[31] | |

| Ellan Vannin | Manx (Gaelg) |

Manx (Manninee) |

70,000 | 1,700[32] | 2.2%[33] | |

| Alba | Scottish Gaelic (Gàidhlig) |

Scots (Albannaich) |

5,000,000 | 92,400[34] | 1.2%[35] | |

| Kernow | Cornish (Kernewek) |

Cornish (Kernowyon) |

500,000 | 2000[36] | 0.1%[37][38] |

Of the languages above, three belong to the Goidelic or Gaelic branch (Irish, Manx, Scottish Gaelic) and three to the Brythonic or Brittonic branch (Welsh, Cornish, Breton). Their names for each other in each language shows some of the differences and similarities:

| Ireland | Scotland | Mann | Wales | Cornwall | Brittany | Great Britain |

Celtic nations Celtic languages | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Irish (Gaeilge)[39] |

Éire | Albain | Manainn | an Bhreatain Bheag |

an Chorn | an Bhriotáin | an Bhreatain Mhór |

Náisiúin Cheilteacha Teangacha Ceilteacha |

| Scottish (Gàidhlig) |

Èirinn | Alba | Manainn | a' Chuimrigh | a' Chòrn | a' Bhreatainn Bheag |

Breatainn Mhòr |

Nàiseanan Ceilteach Cànain Cheilteach |

| Manx (Gaelg) |

Nerin | Nalbin | Mannin | Bretyn | y Chorn | y Vritaan | Bretyn Vooar |

Ashoonyn Celtiagh Çhengaghyn Celtiagh |

| Welsh (Cymraeg) |

Iwerddon | yr Alban | Manaw | Cymru | Cernyw | Llydaw | Prydain Fawr |

Gwledydd Celtaidd Ieithoedd Celtaidd |

| Cornish (Kernewek) |

Iwerdhon | Alban | Manow | Kembra | Kernow | Breten Vian |

Breten Veur |

Gwlasow Keltek Yethow Keltek |

| Breton (Brezhoneg) |

Iwerzhon | Alban/Skos | Manav | Kembre | Kernev | Breizh | Breizh Veur |

Broioù Keltiek Yezhoù Keltiek |

Other claims

This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2008) |

At one point, most countries of Western and Central Europe were mainly Celtic – in terms of language and culture. Today, their Celtic languages have died out and their Celtic cultural traits have mostly (though not wholly) vanished. Since they no longer have a living Celtic language, they are not included as 'Celtic nations'. Nonetheless, some of these countries have 'Celtic' movements who wish their country to be included based on historical grounds. This has caused some controversy.

Due to immigration, a dialect of Scottish Gaelic (Canadian Gaelic) is spoken by some on Cape Breton Island in Nova Scotia, while a Welsh-speaking minority exists in the Chubut Province of Argentina.

Hence, for certain purposes, such as the Festival Interceltique de Lorient– Galicia, Asturias and Cape Breton Island in Nova Scotia are considered three of the nine Celtic nations.[5]

Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula was an area particularly influenced by Celtic culture. In particular almost all of Spain, with the exception of eastern and southern regions as well as in the Pyrenees, and also almost all of Portugal, with the relative exception of the Algarve. As such Spanish regions such as Asturias and Galicia, as well as, to a lesser extent, Northern Portugal, also claim a Celtic identity.

England

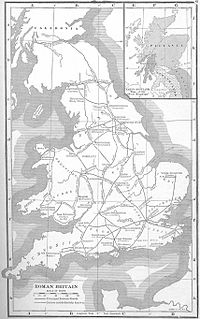

In Celtic languages, England is usually referred to as "Saxon-land" (Sasana, Pow Saws, Bro-Saoz etc), and in Welsh as Lloegr (though the Welsh translation of English (language) also refers to the Saxon route: Saesneg, with the English people being referred to as "Saeson", or "Saes" in the singular). This is because the Celtic peoples of what is now England succumbed to the invading Saxons and were either driven out of their lands, killed or assimilated into the culture of Englalond. However, spoken Cumbric survived until the 12th century, Cornish until the 18th century, and Welsh within the Welsh Marches, notably in Archenfield, now part of Herefordshire, until around the same time. Both Cumbria and Cornwall were traditionally Brythonic in culture and are considered so by many in England; Anglo-Saxon settlement in these areas was historically small. Cornwall existed as an independent state for some time after the foundation of England, and Cumbria originally retained a great deal of autonomy within the Kingdom of Northumbria. The unification of the Anglian kingdom of Northumbria with the Cumbric kingdom of Cumbria came about due to a political marriage between the Northumbrian King Oswiu and Queen Riemmelth. Though the Anglian settlement in Cumbria was as a whole minor, they settled in the Eden valley and along the north and south coasts. The placename Inglewood attests to the Anglian presence, even if it is, by and large, minor.

Movements of population between different parts of Great Britain over the last two centuries, with industrial development and changes in living patterns such as the growth of second home ownership, have greatly modified the demographics of these areas, including the Isles of Scilly off the coast of Cornwall, although Cornwall in particular retains unique cultural features, and a Cornish self-government movement is well established.[40]

Remnants of Brythonic and Cumbric placenames are sometimes seen throughout spots in England but are more common in the West than the East, mainly in the traditionally Celtic areas of Cornwall and Cumbria. Elements such as caer 'fort' as in the Cumbrian city of Carlisle, pen 'hill' as in the Cumvrian town of Penrith and craig 'crag, rock' as in High Crag. The name 'Cumbria' is derived from the same root as Cymru, the Welsh name for Wales, meaning 'the land of comrades'. There is a current attempt to revive Cumbric and about 50 words of a reconstructed, hypothetical "Cumbric" exist.

Formerly Gaulish regions

Many of the French people themselves identify actively with the Gauls.

The French- and Arpitan-speaking Aosta Valley region in Italy also presents a casual claim of Celtic heritage. The Northern League autonomist party often exalts what it claims are the Celtic roots of the entire Northern Italy, or Padania. Reportedly, Friuli also has an ephemeral claim to celticity.

Walloons characterise sometimes themselves as "Celts", mainly opposed to "Teutonic" Flemish and "Latin" French identities; the ethnonym "Walloon" derives from a Germanic word meaning "foreign", cognate with the words "Welsh" and "Vlach". The name of Belgium, home country of the Walloon people, is cognate with the Celtic tribal names Belgae and (possibly) the Irish legendary Fir Bolg.

Central European regions

Celtic tribes inhabited land in what is now southern Germany and Austria.[41] Many scholars have associated the earliest Celtic peoples with the Hallstatt culture.[42] Boii, Scordisci[43] and the Vindelici[44] are some of the tribes that inhabited Central Europe, including what is now Slovakia, Serbia, Croatia, Poland and the Czech Republic as well as Germany and Austria. The Boii gave their name to Bohemia.[45] Celts also founded Singidunum present-day Belgrade, leaving many words in Serbian language (over 5000). The La Tène culture also covered much of central Europe. The name of the culture is from the location in Switzerland.[46]

Outside Europe

In other regions, people with a heritage from one of the 'Celtic nations' also associate with the Celtic identity. In these areas, Celtic traditions and languages are significant components of local culture. These include the Permanent North American Gaeltacht in Tamworth, Ontario, Canada which is the only Irish Gaeltacht outside of Ireland, the Chubut valley of Patagonia with Welsh-speaking Argentinians (known as "Y Wladfa"), Cape Breton Island in Nova Scotia, with Gaelic-speaking Canadians and southeast Newfoundland with Irish-speaking Canadians. Also at one point in 1900's there were well over 12,000 Gaelic Scots from the Isle of Lewis living in the Eastern Townships of Quebec, Canada, with place names that still exist today recalling those inhabitants.

Large swathes of the United States of America were subject to migration from Celtic peoples, or people from Celtic nations. Irish-speaking Irish Catholics congregated particularly in the East Coast cities of New York, Boston, and Philadelphia, while Scots and Ulster-Scots were particularly prominent in the Southern United States, including Appalachia.

An area of Pennsylvania known as the Welsh Tract was settled by Welsh Quakers, where the names of several towns still bear Welsh names, such as Bryn Mawr and Bala Cynwyd.

In his autobiography, the South African poet Roy Campbell recalled his youth in the Dargle Valley, near the city of Pietermaritzburg, where people spoke only Gaelic and Zulu.

In New Zealand the southern regions of Otago and Southland were settled by the Free Church of Scotland. Many of the place names in these two regions (such as the main cities of Dunedin and Invercargill and the major river, the Clutha) have Scottish Gaelic names,[47] and Celtic culture is still prominent in this area.[48][49][50]

In addition to these, a number of people from the USA, Australia, South Africa and other parts of the former British Empire have formed various Celtic societies over the years.

See also

References

- ^ a b c "Who were the Celts? ... Rhagor". Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales website. Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales. 2007-05-04. Retrieved 2009-12-10.

- ^ Celticleague.net

- ^ "Welsh Assembly Government - Celtic countries connect with contemporary Cymru". Welsh Assembly Government website. Welsh Assembly Government. 2008-05-13. Retrieved 2009-05-15.

- ^ "Isle of Man Post Office Website". Isle of Man Post Office website. Isle of Man Government. 2009. Retrieved 2009-05-15.

- ^ a b c "Site Officiel du Festival Interceltique de Lorient". Festival Interceltique de Lorient website. Festival Interceltique de Lorient. 2009. Retrieved 2009-05-15. Cite error: The named reference "Festival 1" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Ian Johnston (2006-09-21). "We're nearly all Celts under the skin". The Scotsman. Retrieved 2007-11-24.

- ^ Lhuyd, Edward (1707). Archaeologia Britannica: an Account of the Languages, Histories and Customs of Great Britain, from Travels through Wales, Cornwall, Bas-Bretagne, Ireland and Scotland. Oxford.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Nathalie Koble, Jeunesse et genèse du royaume arthurien, Paradigme, 2007, ISBN 2868782701, p.145

- ^ The term "Celtic Fringe" gained currency in late-Victorian years (Thomas Heyck, A History of the Peoples of the British Isles: From 1870 to Present, Routledge, 2002, ISBN 0415302331, p.43) and is now widely attested, e.g. Michael Hechter, Internal Colonialism: The Celtic Fringe in British National Development, Transaction Publishers, 1999, ISBN 0765804751; Nicholas Hooper and Matthew Bennett, England and the Celtic Fringe: Colonial Warfare in The Cambridge Illustrated Atlas of Warfare, Cambridge University Press, 1996, ISBN 0521440491

- ^ Ian Hazlett, The Reformation in Britain and Ireland, Continuum International Publishing Group, 2003, ISBN 0567082806, p.21

- ^ "The Celtic League". Celtic League website. The Celtic League. 2010. Retrieved 2010-02-20.

- ^ "Information on The International Celtic Congress Douglas, Isle of Man hosted by". Celtic Congress website (in Irish and English). Celtic Congress. 2010. Retrieved 2010-02-20.

- ^ "Welcome to the Pan Celtic 2010 Home Page". Pan Celtic Festival 2010 website. Fáilte Ireland. 2010. Retrieved 2010-02-20.

- ^ "About the Festival". National Celtic Festival website. National Celtic Festival. 2009. Retrieved 2010-02-20.

- ^ "About Us::Celtic Media Festival". Celtic Media Festival website. Celtic Media Festival. 2009. Retrieved 2010-02-20.

- ^ "Celtic connections:Scotland's premier winter music festival". Celtic connections website. Celtic Connections. 2010. Retrieved 2010-02-20.

- ^ "'Hebridean Celtic Festival 2010 - the biggest homecoming party of the year". Hebridean Celtic Festival website. Hebridean Celtic Festival. 2009. Retrieved 2010-02-20.

- ^ "Magners League:About Us:Contact Information". Magners League website. Magners League. 2009. Retrieved 2010-02-20.

- ^ "scottishathletics-news". scottishathletics website. scottishathletics. 2006-06-14. Retrieved 2010-02-20.

- ^ Coulter, Colin; Coleman, Steve (2003). The end of Irish history?: critical reflections on the Celtic tiger. Manchester: Manchester University Press. p. 83. ISBN 0 7190 6230 6. Retrieved 2010-02-20.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ ""Celtic Tiger" No More - CBS Evening News - CBS News". CBS News website. CBS Interactive. 2009-03-07. Retrieved 2010-02-20.

- ^ "BBC News:Scotland:Salmond gives Celtic Lion vision". BBC News website. BBC. 2007-10-12. Retrieved 2010-02-20.

- ^ "http://www.breizh.net/icdbl/saozg/Celtic_Languages.pdf" (pdf). Breizh.net website. U.S. Branch of the International Comittee for the Defense of the Breton Language. 1995. Retrieved 2008-10-26.

{{cite web}}: External link in|title= - ^ "BBC Wales - The School Gate - About School - The Curriculum at Primary School -". BBC website. BBC. 2010-02-20. Retrieved 2010-02-20.

- ^ a b "BBC News:Education:Local UK languages 'taking off'". BBC News website. BBC. 2009-02-12. Retrieved 2010-02-20.

- ^ a b 2006 Census

- ^ a b The figure for Northern Ireland from the 2001 Census is somewhat ambiguous, as it covers people who have "some knowledge of Irish". Out of the 167,487 people who claimed to have "some knowledge", 36,479 of them could only understand it spoken, but couldn't speak it themselves.

- ^ Welsh Language Board - How many people speak Welsh?

- ^ Main Statistics about Welsh from the Welsh Language Board

- ^ The most recent census (2001) shows about 270,000 speakers. The site oui au breton estimates a yearly decline of about 10,000 speakers, suggesting a number of about 200,000 current speakers. Retrieved 2008-09-24.

- ^ Template:Fr icon Données clés sur breton, Ofis ar Brezhoneg

- ^ 2006 Official Census, Isle of Man

- ^ Gov.im - Culture

- ^ BBC News: Mixed report on Gaelic language

- ^ Kenneth MacKinnon (2003). "Census 2001 Scotland: Gaelic Language – first results". Retrieved 2007-03-24.

- ^ "'South West:TeachingEnglish:British Council:BBC". BBC/British Council website. BBC. 2010. Retrieved 2010-02-20.

- ^ projects.ex.ac.uk - On being a Cornish ‘Celt’: changing Celtic heritage and traditions

- ^ Effectively extinct as a spoken language in 1777. Language revived from 1904, though remains a tiny 0.1% percent being able to hold a limited conversion in Cornish.

- ^ Foclóir Póca (1992) An Gúm

- ^ The Kingdom of Kernow 'exists apart from England' - Telegraph.co.uk, 29 Jan 2010

- ^ Celts - Hallstatt and La Tene cultures

- ^ Celtic Impressions - The Celts

- ^ AncientWorlds.net, 27k

- ^ Vindelici

- ^ Boii - Britannica Online Encyclopedia

- ^ The Early Celts

- ^ Te Ara: Encyclopedia of New Zealand

- ^ ODT.co.nz

- ^ DunedinCelticArts.org.nz

- ^ OtagoCaledonian.org

Further reading

- National Geographic, "The Celtic Realm". March, 2006.

External links

- Celtic League

- Celtic League International

- Celtic League - American Branch

- The Celtic Realm

- Celtic-World.Net, - Various information on Celtic culture and music

- Template:PDFlink

- The Celtic Nations

- Simon James Ancient Celts Page

- an article on Celtic Realms by Jim Gilchrist of The Scotsman

- The Celtic Nations Association