2009 Fort Hood shooting

| Fort Hood shooting | |

|---|---|

Location of the main cantonment of Fort Hood in Bell County, Texas | |

| Location | Fort Hood, Texas, United States |

| Date | November 5, 2009 ca. 1:34 p.m. (CST) |

Attack type | Mass shooting, mass murder |

| Deaths | 13[1] |

| Injured | 30[1] |

The Fort Hood shooting was a mass shooting that took place on November 5, 2009, at Fort Hood—the most populous US military base in the world, located just outside Killeen, Texas—in which a gunman killed 13 people and wounded 30 others.[2]

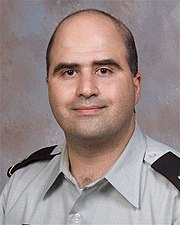

The accused perpetrator is Nidal Malik Hasan, a U.S. Army major serving as a psychiatrist. He was shot by civilian police officers,[3] and is now paralyzed from the waist down.[4] Hasan has been charged with 13 counts of premeditated murder and 32 counts of attempted murder under the Uniform Code of Military Justice; he may face additional charges at court-martial.[5][6]

Hasan is an American-born Muslim of Palestinian descent. Internal Army reports indicate officers within the Army were aware of Hasan's tendencies toward radical Islam since 2005. Additionally, investigations before and after the shooting discovered e-mail communications between Hasan and Anwar al-Awlaki. Imam Awlaki quickly declared Hasan a hero, as "fighting against the U.S. army is an Islamic duty", and was believed to have played a role in the Al Queda-organized attempted terrorist bombing of Northwest Airlines Flight 253. After communications between the two were forwarded to FBI terrorism task forces in 2008, they determined Hasan was not a threat prior to the shooting and that his questions to al-Awlaki were consistent with medical research.

In November 2009, after examining the e-mails and previous terrorism investigations, the FBI had found no information to indicate he had any co-conspirators or was part of a broader terrorist plot. To date, no government agency has officially declared the incident to be an act of terrorism. However, many government officials, polls and public figures have called the shootings an act of Islamic terrorism.

Shootings

At approximately 1:34 p.m. local time Hasan entered his workplace, the Soldier Readiness Center, where personnel receive routine medical treatment immediately prior to and on return from deployment. According to eyewitnesses, he took a seat at an empty table, bowed his head for several seconds,[8] and then stood up and opened fire. Initially, Hasan reportedly jumped onto a desk and shouted: "Allahu Akbar!",[9][10] before firing more than 100 rounds[11] at soldiers processing through cubicles in the center, and on a crowd gathered for a college graduation ceremony scheduled for 2 p.m. in a nearby theater.[12] Witnesses reported that Hasan appeared to focus on soldiers in uniform.[13] He had two handguns: an FN Five-seven semi-automatic pistol, which he had purchased at a civilian gun store,[14] and a .357 Magnum revolver which he may not have fired.[7] A medic who treated Hasan said his combat fatigues pockets were full of pistol magazines.[15]

Unarmed army reserve Captain John Gaffaney attempted to stop Hasan, either by charging the shooter or throwing a chair at him, but was mortally wounded in the process.[16] Base civilian police Sergeant Kimberly Munley, who had arrived on the scene in response to the report of an emergency at the center, encountered Hasan exiting the building in pursuit of a wounded soldier. Hasan shot Munley, while witnesses claim Munley also fired at Hasan. Munley was hit three times: twice through her left leg and once in her right wrist, knocking her to the ground.[17] In the meantime, civilian police officer Sergeant Mark Todd arrived and fired at Hasan. Todd said: "He was firing at people as they were trying to run and hide. Then he turned and fired a couple of rounds at me. I didn't hear him say a word, he just turned and fired."[18] Hasan was felled by shots from Todd,[3][19] who then kicked a pistol out of Hasan's hand, and placed him in handcuffs as he fell unconscious.[20]

The incident, which lasted about 10 minutes,[21] resulted in 30 people wounded, and 13 killed—12 soldiers and 1 civilian; 11 died at the scene, and 2 died later in a hospital.[22][23]

Initially, three soldiers were believed to have been involved in the shooting; two other soldiers were detained, but subsequently released. The Fort Hood website posted a notice indicating that the shooting was not a drill. Immediately after the shooting, the base and surrounding areas were locked down by military police and SWAT teams until around 7 p.m. local time.[24] In addition, Texas Rangers, Texas DPS troopers,[25] deputies from the Bell County Sheriff's Office, and FBI agents from Austin and Waco were dispatched.[26] U.S. President Barack Obama was briefed on the incident and later made a statement about the shooting.[1]

Casualties

There were 43 shooting casualties. Among the 13 killed were 12 soldiers, 1 of whom was pregnant, and a single Army civilian employee. 30 others were wounded and required hospitalization.[1][2] Hasan, the alleged gunman, was taken to Brooke Army Medical Center in Fort Sam Houston, Texas, where he is being held under heavy guard.[4] He was hit by at least four shots,[27] and is said to be paraplegic.[4]

Ten of the injured were treated at Scott & White Memorial Hospital, a Level 1 trauma center in Temple, Texas.[28] Seven more wounded victims were taken to Metroplex Adventist Hospital in Killeen.[28] Eight others received hospital treatment for shock.[2] Of those wounded at least 17 were service-members, and at least 7 were civilians.[29] On November 20 it was announced that eight of the wounded service-members will still deploy overseas.[30]

Fatalities

The 13 killed were:

| Name | Age | Hometown | Rank or occupation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Michael Grant Cahill[31] | 62 | Spokane, Washington | Civilian Physician Assistant |

| Libardo Eduardo Caraveo[32] | 52 | Woodbridge, Virginia | Major |

| Justin Michael DeCrow[33] | 32 | Plymouth, Indiana | Staff Sergeant |

| John P. Gaffaney[34] | 56 | Serra Mesa, California | Captain[35] |

| Frederick Greene[31] | 29 | Mountain City, Tennessee | Specialist |

| Jason Dean Hunt[31] | 22 | Tipton, Oklahoma | Specialist |

| Amy Sue Krueger[31] | 29 | Kiel, Wisconsin | Staff Sergeant |

| Aaron Thomas Nemelka[31] | 19 | West Jordan, Utah | Private First Class |

| Michael S. Pearson[36] | 22 | Bolingbrook, Illinois | Private First Class |

| Russell Gilbert Seager[29] | 51 | Racine, Wisconsin | Captain[37] |

| Francheska Velez ‡[38] | 21 | Chicago, Illinois | Private First Class |

| Juanita L. Warman[29] | 55 | Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania | Lieutenant Colonel[39] |

| Kham See Xiong[31] | 23 | Saint Paul, Minnesota | Private First Class |

- ‡ Francheska Velez was pregnant at the time of her death.[40]

Suspect

Major Nidal Malik Hasan, MD, a 39-year-old U.S. Army psychiatrist of Palestinian descent, is the sole suspect in the shootings. Hasan is a practicing Muslim who, according to one of his cousins, became more devout after the deaths of his parents in 1998 and 2001.[41] His cousin did not recall him ever expressing radical or anti-American views.[41] Another cousin, Nader Hasan, a lawyer in Virginia, said that Nidal Hasan's opinion turned against the wars after he heard stories from people who returned from Afghanistan and Iraq.[42]

Hasan attended the Dar Al-Hijrah mosque in Falls Church, Virginia, in 2001, at the same time as Nawaf al-Hazmi and Hani Hanjour, two of the hijackers in the September 11 attacks.[43][44] A law enforcement official said that the FBI will probably look into whether Hasan associated with the hijackers.[45] A review of Hasan's computer and his multiple e-mail accounts has revealed visits to websites espousing radical Islamist ideas, a senior law enforcement official said.[46]

Once, while presenting what was supposed to be a medical lecture to other psychiatrists, Hasan instead talked about Islam, and stated that non-believers would be sent to hell, decapitated, set on fire, and have burning oil poured down their throats. A Muslim psychiatrist in the audience raised his hand, and challenged Hasan's claims.[47] According to Associated Press, Hasan's lecture also "justified suicide bombings."[48]

According to National Public Radio (NPR), officials at Walter Reed Medical Center repeatedly expressed concern about Hasan's behavior during the entire six years he was there; Hasan's supervisors gave him poor evaluations and warned him that he was doing substandard work. In the spring of 2008 (and on later occasions) several key officials met to discuss what to do about Hasan. Attendees of these meetings reportedly included the Walter Reed chief of psychiatry, the chairman of the USUHS Psychiatry Department, two assistant chairs of the USUHS Psychiatry Department (one of whom was the director of Hasan's psychiatry fellowship), another psychiatrist, and the director of the Walter Reed psychiatric residency program. According to NPR, fellow students and faculty were strongly troubled by Hasan's behavior, which they described as "disconnected," "aloof," "paranoid," "belligerent," and "schizoid."[49]

Hasan has expressed admiration for the teachings of Anwar al-Awlaki, imam at the Dar al-Hijrah mosque between 2000 and 2002.[50] Al-Awkali was under surveillance, and Hasan was investigated by the FBI after intelligence agencies intercepted 18 emails between them between December 2008 and June 2009. In one of the emails Hasan wrote: "I can't wait to join you" in the afterlife. Lt. Col. Tony Shaffer, a military analyst at the Center for Advanced Defense Studies, suggested that Hasan was "either offering himself up or [had] already crossed that line in his own mind." Hasan also asked al-Awlaki when jihad is appropriate, and whether it is permissible if innocents are killed in a suicide attack.[51]

Army employees were informed of the contacts, but no threat was perceived; the emails were judged to be consistent with mental health research about Muslims in the armed services.[52] A DC-based joint terrorism task force that operates under the FBI was notified, and the information reviewed by one of its Defense Criminal Investigative Service employees, who concluded there was not sufficient information for a larger investigation.[53] Despite two Defense Department investigators on two joint task forces having looked into Hasan's communications, higher-ups at the Department of Defense stated they were not notified before the incident of such investigations.[54]

In March 2010, Al-Awlaki alleged that the Obama administration attempted to portray Hasan's actions as an individual act of violence from an estranged individual, and that it attempted to suppress information to cushion the reaction of the American public. He said:

- Until this moment the administration is refusing to release the e-mails exchanged between myself and Nidal. And after the operation of our brother Umar Farouk the initial comments coming from the administration were looking the same -- another attempt at covering up the truth. But Al Qaeda cut off Obama from deceiving the world again by issuing their statement claiming responsibility for the operation.[55]

In July 2009 he was transferred from Washington's Walter Reed Medical to Fort Hood.

Hasan gave away furniture from his home on the morning of the shooting, saying he was going to be deployed.[56][57] He also handed out copies of the Qur'an, along with his business cards which listed a Maryland phone number and read "Behavioral Heatlh [sic] – Mental Health – Life Skills | Nidal Hasan, MD, MPH | SoA(SWT) | Psychiatrist".[56][57] According to investigators, the acronym "SoA" is commonly used on jihadist websites as an acronym for "Soldier of Allah" or "Servant of Allah", and SWT is commonly used by Muslims to mean "subhanahu wa ta'ala" (Glory to God).[58] The cards did not reflect his military rank.

Possible motivation

Immediately after the shooting, analysts and public officials openly debated Hasan's motive and preceding psychological state: A military activist, Selena Coppa, remarked that Hasan's psychiatrist colleagues "failed to notice how deeply disturbed someone right in their midst was."[18] A spokesperson for U.S. Senator Kay Bailey Hutchison, one of the first officials to comment on Hasan's background,[59] told reporters that Hasan was upset about his deployment to Afghanistan on November 28.[60][61] Noel Hamad, Hasan's aunt,[62] said that the family was not aware he was being sent to Afghanistan.[63]

The Dallas Morning News reported on November 17 that ABC News, citing anonymous sources, reported that investigators suspect that the shootings were triggered by superiors' refusal to process Hasan’s requests that some of his patients be prosecuted for war crimes based on statements they made during psychiatric sessions with him. Dallas attorney Patrick McLain, a former Marine, opined that Hasan may have been legally justified in reporting what patients disclosed, but that it was impossible to be sure without knowing exactly what was said, while fellow psychiatrists complained to superiors that Hasan's actions violated doctor-patient confidentiality.[64]

U.S. Senator Joseph Lieberman called for a probe by the Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, which he chairs. Lieberman said "it's premature to reach conclusions about what motivated Hasan ... I think it's very important to let the Army and the FBI go forward with this investigation before we reach any conclusions."[65][66] Two weeks later, Lieberman labeled the shooting "the most destructive terrorist attack on America since September 11, 2001."[67]

Michael Welner, M.D., a leading forensic psychiatrist with experience examining mass shooters, said that the shooting had elements common to both ideological and workplace mass shootings.[68] Welner, who believed the motivation was to create a "spectacle", said that a trauma care worker, even one afflicted with stress, would not be expected to be homicidal toward his patients unless his ideology trumped his Hippocratic oath–and this was borne out in his shouting "Allahu Akhbar" as he killed the unarmed.[68] An analyst of terror investigations, Carl Tobias, opined that the attack did not fit the profile of terrorism, and was more reminiscent of the Virginia Tech shooting.[69]

However, Michael Scheuer, the retired former head of the Bin Laden Issue Station, and former U.S. Attorney General Michael Mukasey[70] have called the event a terrorist attack,[69] as has terrorism expert Walid Phares.[71] Retired General Barry McCaffrey said on Anderson Cooper 360° that "it's starting to appear as if this was a domestic terrorist attack on fellow soldiers by a major in the Army who we educated for six years while he was giving off these vibes of disloyalty to his own force."[72]

Some of Hasan's former colleagues have said he performed substandard work and occasionally unnerved them by expressing fervent Islamic views and deep opposition to the U.S.-led wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.[73]

Brian Levin of the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism wrote that the case sits at the crossroads of crime, terrorism and mental distress.[74] He compared the possible role of religion to the beliefs of Scott Roeder, a Christian who murdered Dr. George Tiller, who practiced abortion. Such offenders "often self-radicalize from a volatile mix of personal distress, psychological issues, and an ideology that can be sculpted to justify and explain their anti-social leanings."[74]

Hasan's family has called the shooting "despicable and deplorable." They are currently working with Virginia law enforcement.[75]

Reaction

In the hours after the shooting, other U.S. military bases stepped up their security measures.[76][77] In an open letter to President Obama, the Fort Hood Iraq Veterans Against the War chapter in part demanded that the military radically overhaul its mental health care system and halt the practice of repeated deployment of the same troops.[78]

Lieutenant General Robert W. Cone, commander of III Corps at Fort Hood, called the attack "a terrible tragedy, stunning", saying the base community was "absolutely devastated."[79] He said that terrorism was not being ruled out, but preliminary evidence did not suggest that the shooting was terrorism.[80] A spokesman for the Defense Department called the shooting an "isolated and tragic case",[81] and Defense Secretary Robert Gates pledged that his department would do "everything in its power to help the Fort Hood community get through these difficult times."[82] The chair of the Senate Armed Services Committee, Carl Levin, and numerous politicians, expressed condolences to the victims and their families.[1][82][83][84]

The U.S. President's initial response to the attack came as he was about to make a speech at the Tribal Nations Conference for America’s 564 federally recognized Native American tribes. Obama has been criticized by the media for not opening his speech by addressing the shooting, and for using colloquialisms in opening remarks before mentioning the incident.[85][86][87]

Homeland Security Secretary Janet Napolitano stated "we object to—and do not believe—that anti-Muslim sentiment should emanate from this ... This was an individual who does not, obviously, represent the Muslim faith."[88] Chief of Staff Gen. George W. Casey, Jr. said "I'm concerned that this increased speculation could cause a backlash against some of our Muslim soldiers ... Our diversity, not only in our Army, but in our country, is a strength. And as horrific as this tragedy was, if our diversity becomes a casualty, I think that’s worse."[89]

The League of United Latin American Citizens issued a statement referring to the loss of a "LULAC family member".[90] President of the Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence, Paul Helmke, said that "This latest tragedy, at a heavily fortified army base, ought to convince more Americans to reject the argument that the solution to gun violence is to arm more people with more guns in more places."[91] However, Lt. General Cone stated the on-base firearm policy: "As a matter of practice, we do not carry weapons on Fort Hood. This is our home."[92] Military weapons are only used for training or by base security, and personal weapons must be kept locked away by the provost marshal.[93] Specialist Jerry Richard, a soldier working at the Readiness Center, expressed the opinion that this policy had left them unnecessarily vulnerable to violent assaults: "Overseas you are ready for it. But here you can't even defend yourself."[94]

The Council on American-Islamic Relations condemned the shooting, expressing prayers for the victims and condolences for their families.[95][96] Salman al-Ouda,[97] a dissident Saudi cleric and former inspiration to Osama bin Laden, condemned the shooting saying the incident would have bad consequences: "...undoubtedly this man might have a psychological problem; he may be a psychiatrist but he [also] might have had psychological distress, as he was being commissioned to go to Iraq or Afghanistan, and he was capable of refusing to work whatever the consequences were." The senior analyst at the NEFA Foundation described Ouda’s comments as "a good indication of how far on a tangent Anwar al-Awlaki is."[98]

Soon after the attack, Anwar al-Awlaki posted praise for Hasan for the shooting on his website, and encouraged other Muslims serving in the military to "follow in the footsteps of men like Nidal."[50] "Nidal Hasan is a hero, the fact that fighting against the U.S. army is an Islamic duty today cannot be disputed. Nidal has killed soldiers who were about to be deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan in order to kill Muslims."[99] Adam Yahiye Gadahn, the American-born al-Qaeda spokesman, declared Hasan a "pioneer" whose actions at Fort Hood should be followed by other Muslims.[100]

Investigation and prosecution

The criminal investigation is being conducted jointly by the FBI, the U.S. Army Criminal Investigation Command, and the Texas Rangers Division.[101] As a member of the military, Hasan is subject to the jurisdiction of the Uniform Code of Military Justice (military law). He is being represented by Belton, Texas-based John P. Galligan, a criminal defense attorney and retired US Army Colonel.[102] Hasan regained consciousness on November 9, but refused to talk to investigators.[103] The investigative officer in charge of his article 32 hearing is Colonel James L. Pohl, who had previously lead the Abu Ghraib abuses, and is the Chief Presiding Officer of the Guantanamo military commissions.[104]

On November 9, the FBI said that investigators believed Hasan had apparently acted alone. They disclosed that they had reviewed evidence which included 2008 conversations with an individual that an official identified as Anwar al-Awlaki, but said they did not find any evidence that Hasan had direct help or outside orders in the shootings.[105] According to a November 11 press release, after preliminary examination of Hasan’s computers and internet activity, they had found no information to indicate he had any co-conspirators or was part of a broader terrorist plot "at this point" of what they stressed were the "early stages" of the review.[101] Though Hasan had frequented jihadist web sites promoting radical Islamic views, they said no e-mail communications with outside facilitators or known terrorists were found. An official said, though, that the investigation is "fluid and still in its early stages." Investigators were evaluating reports that, in 2001, Hasan had attended a mosque in Virginia headed by Anwar al-Awlaki and attended by two of the 9/11 hijackers. The radical imam was living in Yemen, and had been accused of aiding the 9/11 plot. Investigators were determining if al-Awlaki's teachings could have radicalized Hasan. Sources said "We need to look at potential inspiration."[106]

Army officials stated "Right now we're operating on the belief that he acted alone and had no help". No motive for the shootings was offered, but they believed Hasan had authored an Internet posting that appeared to support suicide bombings.[107] Senator Lieberman opined "if the reports that we're receiving of various statements he made, acts he took, are valid, he had turned to Islamist extremism." Rep. John Carter remarked "When he shouted 'Allahu Akbar,' he gave a clear indication that his faith or Muslim view of the world had something to do with it."[107]

In pressing charges on Hasan, the Department of Defense and the DoJ agreed that Hasan would be prosecuted in a military court, which observers noted was consistent with investigators concluding he had acted alone.[108]

During a November 21 hearing in Hasan's hospital room, a magistrate ruled that there was probable cause that Hasan committed the November 5 shooting, and ordered that he be held in pre-trial confinement after he is released from hospital care.[88] On November 12 and December 2, respectively, Hasan was charged with 13 counts of premeditated murder and 32 counts of attempted murder by the Army; he may face additional charges at court-martial.[5][6]

A 14th count of murder for the death of the unborn child of Francheska Velez has not been filed.[109] Such charge is available to prosecutors under the Unborn Victims of Violence Act and Article 119a of the Uniform Code of Military Justice.[110] If civilian prosecutors indict him for being part of a terrorist plot, it could justify moving all or part of his case into federal criminal courts under U.S. anti-terrorism laws.[111][112]

The military justice system rarely carries out capital punishment—even in mass murder cases—and no executions have been carried out since 1961.[112][113] (From 1916 to 1961, the U.S. Army executed 135 people.)[114] A Rasmussen national survey found that 65% of Americans favored the death penalty in Hasan's case, and that 60% want the case investigated as an act of terrorism.[115]

Internal investigations

The FBI noted that Hasan had first been brought to their attention in December 2008 by a Joint Terrorism Task Force (JTTF). Communications between Hasan and al-Awlaki, and other similar communications, were reviewed and considered to be consistent with Hasan's research on radical beliefs at the Walter Reed Medical Center. "Because the content of the communications was explainable by his research and nothing else derogatory was found, the JTTF concluded that Major Hasan was not involved in terrorist activities or terrorist planning." However, both the FBI and the Department of Defense plan to review if this assessment was handled correctly.[108]

FBI Director Robert Mueller appointed William Webster, a former director of the FBI, to conduct an independent FBI review of the bureau's handling of possible warning signs from Hasan. The review is expected to be long-term and in-depth, with Webster selected for the job due to being, as Mueller put it, "uniquely qualified" for such a review.[116]

On January 15, 2010, the Department of Defense released the findings of the the Department of Defense investigation. That review found that the Department was unprepared to defend against internal threats. Secretary Robert Gates said that previous incidents had not drawn enough attention to workplace violence and "self-radicalization" within the military. He also suggested that some officials may be held responsible for not drawing attention to Hasan prior to the shooting.[117] The Department report did not touch upon Hasan's motivations, including his multiple contacts with Anwar al-Awlaki, and his yelling "Allahu Akhbar" as he began the attack. The leaders of the investigation, former Secretary of the Army Togo West and retired Admiral Vernon Clark, responded to criticism by saying their "concern is with actions and effects, not necessarily with motivations", and that they did not want to conflict with the criminal investigation on Hasan that was under way.[118]

James Corum, a retired Army Reserve Lieutenant Colonel and Dean at the Baltic Defence College in Estonia, called the Defense Department report "a travesty", for failing to mention Hasan's devotion to Islam and his radicalization prior to the attack.[119] Texas Representative John Carter was also critical of the report, saying he felt the government was "afraid to be accused of profiling somebody".[120] John Lehman, a member of the 9/11 Commission and Secretary of the Navy under Ronald Reagan, said he felt that the report "shows you how deeply entrenched the values of political correctness have become."[118] Similarly, columnist Debra Saunders of the San Francisco Chronicle, in a column entitled "Political correctness on Fort Hood at Pentagon," wrote: "Even ... if the report's purpose was to craft lessons to prevent future attacks, how could they leave out radical Islam?"[121]

After Louay Safi received complaints about his lectures about Islam at Fort Hood after the incident, the Dallas Morning News was informed in January that Safi was under investigation and that his lectures had been suspended. Thirteen Republican members of Congress asked Defense Secretary Robert Gates on Dec. 17 to halt lectures by anyone affiliated with ISNA on military bases. [122]

In February 2010 the Boston Globe was given access to an internal report detailing results of the Army's investigation. The report was not made public to protect the identities of officers who may face disciplinary action. According to the Globe, it concludes officers within the Army were aware of Hasan's tendencies toward radical Islam since 2005. The report adduced one incident in 2007 in which Hasan gave a classroom presentation titled "Is the War on Terrorism a War on Islam: An Islamic Perspective". The instructor interrupted Hasan's presentation as it appeared he was justifying terrorism, according to the Globe. Despite receiving complaints about this presentation, and other statements suggestive of his conflicted loyalties, Hasan's superior officers took no action, believing Hasan's comments were protected under the First Amendment and that having a Muslim psychiatrist contributed to diversity. The investigation noted the First Amendment does not apply to soldiers the same way as for civilians, and his statements might have been grounds for removing him from service.[123]

See also

- 1995 William Kreutzer, Jr. case – convicted of killing an officer and wounding 17 other soldiers at Fort Bragg, North Carolina.

- 2003 Hasan Akbar case – convicted of murder of two officers at Camp Pennsylvania, Kuwait.

- 2007 Fort Dix attack plot – six radical Islamist men convicted of plotting an attack on Fort Dix, New Jersey.

- 2009 Camp Liberty killings – Sgt. John M. Russell charged with five counts of murder and one count of aggravated assault for attack at Camp Liberty, Iraq.

- 2009 Lloyd R. Woodson case—Arrested with military-grade illegal weapons he intended to use in a violent crime, and a detailed map of the Fort Drum military installation

References

- ^ a b c d e "Neighbors: Alleged Fort Hood gunman emptied apartment". Fort Hood, Texas: CNN. November 6, 2009. Retrieved November 6, 2009.

- ^ a b c "Lawmakers' briefing causes confusion on wounded". Associated Press. November 6, 2009.

- ^ a b McCloskey, Megan, "Civilian police officer acted quickly to help subdue alleged gunman", Stars and Stripes, November 8, 2009.

- ^ a b c Austin American-Statesman, November 7, 2009

- ^ a b "Fort Hood suspect charged with murder". Fort Hood, Texas: CNN. November 12, 2009. Retrieved November 12, 2009.

- ^ a b "Army adds charges against rampage suspect". MSNBC. December 2, 2009. Retrieved December 3, 2009.

- ^ a b Cuomo, Chris (November 6, 2009). "Alleged Fort Hood Shooter Nidal Malik Hasan Was 'Calm,' Methodical During Massacre". ABC News. Retrieved November 6, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Peter baker and Clifford Krauss (November 10, 2009), found at "President, at Service, Hails Fort Hood’s Fallen,", New York Times. Retrieved November 11, 2009. Cite error: The named reference "NYT 8" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "Fort Hood shootings: the meaning of 'Allahu Akbar'". The Daily Telegraph. November 6, 2009. Retrieved November 6, 2009.

- ^ "Local Soldier Describes Fort Hood Shooting". KMBC-TV Kansas City Ch.9. November 6, 2009. Retrieved November 6, 2009.

- ^ "Survival, courage in tragedy at Fort Hood". Kansascity.com. November 6, 2009. Retrieved November 10, 2009.

- ^ Anne (November 5, 2009). "Army: At least 1 Hood shooter in custody". Military Times. Retrieved November 5, 2009.

- ^ McKinley, James C. Jr., "After Years Of Growing Tensions, 7 Minutes Of Bloodshed", New York Times, November 9, 2009, p. 1.

- ^ "AP Sources: 1 rampage gun purchased legally". Retrieved November 8, 2009.

- ^ "Hash Browns, Then 4 Minutes of Chaos". Wall Street Journal. November 7, 2009. Retrieved November 7, 2009.

- ^ Gregg Zoroya (USA Today). "Witnesses say reservist was a hero at Hood". Retrieved November 26, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ McKINLEY Jr., JAMES (November 12, 2009). "Second Officer Gives an Account of the Shooting at Ft. Hood". New York Times. Retrieved November 12, 2009.

- ^ a b Allen, Nick (November 8, 2009). "Fort Hood gunman had told U.S. military colleagues that infidels should have their throats cut". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved November 9, 2009.

- ^ Breed, Allen G. (November 6, 2009). "Soldiers say carnage could have been worse". Military Times. Retrieved November 7, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Root, Jay (Associated Press), "Officer Gives Account Of The Firefight At Fort Hood", Arizona Republic, November 8, 2009.

- ^ Powers, Ashley (November 6, 2009). "Tales of terror and heroism emerge from Ft. Hood". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 6, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Gunman kills 12, wounds 31 at Fort Hood". MSNBC. November 5, 2009. Retrieved November 6, 2009.

- ^ Jayson, Sharon (November 6, 2009). "'Horrific' rampage stuns Army's Fort Hood". USA Today. Retrieved November 6, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Officials: Fort Hood no longer on lockdown; suspect identified". The Statesman. November 5, 2009. Retrieved November 6, 2009.

- ^ "Perry sends Rangers to help secure Fort Hood". Houston Chronicle. November 5, 2009. Retrieved November 5, 2009.

- ^ "Twelve shot dead at US army base". BBC News. November 5, 2009. Retrieved November 5, 2009.

- ^ Carlton, Jeff (November 6, 2009). "Ft. Hood suspect reportedly shouted `Allahu Akbar'". Associated Press. Retrieved November 6, 2009.

- ^ a b "Local hospitals treating victims". The Statesman. November 5, 2009. Retrieved November 5, 2009.

- ^ a b c "Fort Hood shooting victims". My San Antonio. November 7, 2009. Retrieved November 7, 2009.

- ^ Gregg Zoroya — USA TODAY (November 19, 2009). "8 Fort Hood wounded will still deploy". Army Times. Retrieved November 20, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f "Fort Hood victims: Sons, a daughter, mother-to-be". CNN. November 6, 2009. Retrieved November 7, 2009.

- ^ Younger, Jamar (November 7, 2009). "Ex-Tucson teacher among dead at Ft. Hood". Arizona Daily Star. Retrieved November 7, 2009.

- ^ Ryckaert, Vic (November 7, 2009). "Hoosier killed in shooting joined Army in search of a better life". The Indianapolis Star. Retrieved November 7, 2009.

- ^ Kucher, Karen (November 6, 2009). "Serra Mesa Army reservist among those killed at Fort Hood". San Diego Union Tribune. Retrieved November 7, 2009.

- ^ WSJ Staff (November 6, 2009). "Fort Hood Profiles: Capt. John Gaffaney". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved November 7, 2009.

- ^ "Bolingbrook Soldier Among 13 Killed At Fort Hood". CBS Chicago. November 6, 2009. Retrieved November 6, 2009.

- ^ WSJ Staff (November 8, 2009). "Fort Hood Profiles: Capt. Russell Seager". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved November 8, 2009.

- ^ "Army families mourn bright lives cut short". The Chicago Tribune. November 7, 2009. Retrieved November 7, 2009.

- ^ WSJ Staff (November 9, 2009). "Fort Hood Profiles: Lt. Col. Juanita Warman". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved November 9, 2009.

- ^ Peter Slevin (November 6, 2009). "Francheska Velez, who had disarmed bombs in Iraq, was pregnant and headed home". Washington Post.

- ^ a b Dao, James (November 5, 2009). "Suspect Was 'Mortified' About Deployment". New York Times. Retrieved November 7, 2009.

- ^ "Sources Identify Major as Gunman in Deadly Shooting Rampage at Fort Hood". Fox News. November 5, 2009. Retrieved November 6, 2009.

- ^ "Fort Hood shooting: Texas army killer linked to September 11 terrorists". The Telegraph. November 7, 2009.

- ^ "Alleged Shooter Tied to Mosque of 9 / 11 Hijackers". The New York Times. November 8, 2009.

- ^ Matthew Lysiak and Samuel Goldsmith, "Fort Hood suspect Nidal Malik Hasan attended same mosque as two 9/11 terrorists", November 8, 2009, accessed December 10, 2009

- ^ Hsu, Spencer S., and Johnson, Carrie, "Links to imam followed in Fort Hood investigation", Washington Post, November 8, 2009, accessed December 11, 2009

- ^ Officials Begin Putting Shooting Pieces Together, NPR, November 6, 2009

- ^ Clear warning signs, Hasan’s colleagues say, Associated Press/MSNBC, November 7, 2009

- ^ Walter Reed Officials Asked: Was Hasan Psychotic?, NPR, November 11, 2009

- ^ a b By Pamela Hess and Eileen Sullivan (AP) (November 9, 2009). "Radical imam praises alleged Fort Hood shooter". Google.com. The Associated Press:. Retrieved November 10, 2009.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Ross, Brian, and Schwartz, Rhonda, "Major Hasan's E-Mail: 'I Can't Wait to Join You' in Afterlife; American Official Says Accused Shooter Asked Radical Cleric When Is Jihad Appropriate?," ABC News, November 19, 2009, accessed November 19, 2009

- ^ "FBI reassessing past look at Fort Hood suspect". Seattle Times. November 10, 2009.

- ^ "Hasan's Ties Spark Government Blame Game". CBS News. November 11, 2009.

- ^ Martha Raddatz, Brian ross, Mary-Rose Abraham, Rehab El-Buri, Senior Official: More Hasan Ties to People Under Investigation by FBI, November 10, 2009.

- ^ RAW DATA: "Partial Transcript of Radical Cleric's Tape", Fox News, March 18, 2010, accessed March 21, 2010

- ^ a b "Who is Maj. Milik Hasan?". KXXV. November 6, 2009. Retrieved November 6, 2009.

- ^ a b Plunkett, Jack. "AP Photo". Associated Press. Retrieved November 10, 2009.

This photograph taken on Friday, Nov. 6, 2009 in Killeen, Texas, shows a copy of the Quran and a briefcase holding this business card that Maj. Nidal Malik Hasan gave to his neighbor a day before going on a shooting spree at the Fort Hood Army Base.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Esposito, Richard (November 12, 2009). "Major Hasan: Soldier of Allah; Many Ties to Jihad Web Sites". ABC News. Retrieved November 13, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Brown, Jeffrey (November 5, 2009). "A Search for Answers Following Fort Hood Attack". The NewsHour with Jim Lehrer. Retrieved November 14, 2009.

- ^ Newman, Maria (November 5, 2009). "12 Dead, 31 Wounded in Base Shootings". The New York Times. Retrieved November 5, 2009.

- ^ Barnes, Julian (November 6, 2009). "Fort Hood victims bound for Dover Air Force Base". KFSM, LA Times. Retrieved November 6, 2009.

- ^ Durawa, Kevin; (November 6, 2009). News10 Alleged Fort Hood Shooter in a Coma http://www.news10.net/news/local/story.aspx?storyid=69941 Alleged Fort Hood Shooter in a Coma. Retrieved November 11, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Check|url=value (help); Missing or empty|title=(help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Military: Fort Hood suspect is alive". USA Today. November 5, 2009. Retrieved November 6, 2009.

- ^ Eggerton, Brooks (November 17, 2009). "Fort Hood captain: Hasan wanted patients to face war crimes charges". Dallas Morning News. Retrieved November 17, 2009.

- ^ "CQ Transcript: Reps. Van Hollen, Pence, Sen. Lieberman Gov.-elect McDonnell on 'Fox News Sunday'". November 8, 2009. Retrieved November 9, 2009.

- ^ Johnson, Bridget (November 9, 2009). "Lieberman wants probe into 'terrorist attack' by major on Fort Hood". The Hill. Retrieved November 9, 2009.

- ^ "Army base shooting was 'terrorist attack': US lawmaker". AFP. Google. November 18, 2009. Retrieved November 18, 2009.

- ^ a b Fort Hood Mass Shooter Major Hasan was not a 'sleeper' says Forensic Psychiatrist Dr. Michael Welner, http://www.newenglishreview.org/blog_display.cfm/blog_id/23960

- ^ a b "Terrorism or Tragic Shooting? Analysts Divided on Fort Hood Massacre". Fox News. November 7, 2009. Retrieved November 8, 2009.

The authorities have not ruled out terrorism in the shooting, but they said the preliminary evidence suggests that it wasn't.

- ^ Reilly, Ryan (November 9, 2009). "Mukasey Says Fort Hood Attack Was Terrorism". Main Justice. Retrieved November 11, 2009.

- ^ Phares, Walid (November 6, 2009). "Ft. Hood: The Largest 'Terror Act' Since 9/11?". Fox News. p. FoxForum. Retrieved November 8, 2009.

- ^ "Investigating Fort Hood Massacre". Anderson Cooper 360°. November 6, 2009. Retrieved November 7, 2009.

- ^ Yochi j. dreazen (November 17, 2009). Wall Street Journal http://online.wsj.com/article/SB125840811012651161.html?mod=WSJ_hpp_MIDDLENexttoWhatsNewsForth.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ a b Levin, Brian (November 8, 2009). "The Ft. Hood Massacre: A Lone-Wolf Jihad of One?". Huffington Post. Retrieved November 10, 2009.

{{cite web}}: More than one of|author=and|last=specified (help) - ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ "Local Forts Increase Security". myfoxny.com. November 5, 2009. Retrieved November 5, 2009.

- ^ "Fort Hood shootings: Utah families on base". ABC 4 News. November 5, 2009. Retrieved November 5, 2009.

- ^ "Veterans Day message to President Obama | Iraq Veterans Against the War". Ivaw.org. Retrieved November 12, 2009.

- ^ "Fort Hood shootings". Huffington Post. November 5, 2009. Retrieved November 5, 2009.

- ^ McFadden, Robert D. (November 5, 2009). "Army Doctor Held in Ft. Hood Rampage". The New York Times. Retrieved November 8, 2009.

- ^ "Military calls Fort Hood shooting 'isolated' case". MSNBC. November 5, 2009. Retrieved November 5, 2009.

- ^ a b Leinwand, Donna (November 5, 2009). "Army: 12 dead in attacks at Fort Hood, Texas". USA Today. Retrieved November 6, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Biden reacts to Hood attack". politico.com. November 5, 2009. Retrieved November 6, 2009.

- ^ "Sen. Cornyn: Don't jump to conclusions over Fort Hood shootings". Fort Hood, Texas: CNN. November 5, 2009. Retrieved November 5, 2009.

- ^ "Obama's Frightening Insensitivity Following Shooting". NBC Chicago. November 6, 2009. Retrieved November 10, 2009.

- ^ "Barack Obama 'insensitive' over his handling of Fort Hood shooting". Times Online. November 9, 2009. Retrieved November 10, 2009.

- ^ Charles Hurt, "Commander sets the right tone for once," New York Post, November 11, 2009, found at New York Post website. Retrieved November 11, 2009.

- ^ a b "Napolitano Warns Against Anti-Muslim Backlash". Fox News. AP. November 8, 2009. Retrieved November 10, 2009.

- ^ Zakaria, Tabassum (November 8, 2009). "General Casey: diversity shouldn't be casualty of Fort Hood". Reuters. Retrieved November 10, 2009.

- ^ "LULAC National President Rosa Rosales Issues Statement on Fort Hood Shooting | LULAC-League of United Latin American Citizens". Lulac.org. November 6, 2009. Retrieved November 12, 2009.

- ^ "Statement on Fort Hood Tragedy". Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence. November 6, 2009. Retrieved November 8, 2009.

- ^ Daniel, Lisa (November 5, 2009). "Army Major Declared Sole Suspect in Hood Shooting". American Forces Press Service.

- ^ Abcarian, Robin (November 6, 2009). "Fort Hood shooting: Suspected gunman not among fatalities: Army psychiatrist blamed in Fort Hood shooting rampage". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 8, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Twelve dead, 31 wounded in Fort Hood shootings". Stars and Stripes. November 5, 2009. Retrieved November 5, 2009.

- ^ "Muslim group condemns Hood shootings". Military Times. Washington, D.C. November 5, 2009. Retrieved November 6, 2009.

- ^ "Fort Hood shooting: Muslim groups fear backlash". Telegraph. November 6, 2009. Retrieved November 6, 2009.

- ^ the alternate spelling 'Awdah' is used in the source text

- ^ Rawnsley, Adam; Bin Laden’s Spiritual Mentor Condemns Ft. Hood Attacks, Wired.com, November 16, 2009. Retrieved November 16, 2009.

- ^ Michael Isikoff (November 9, 2009). Newsweek http://blog.newsweek.com/blogs/declassified/archive/2009/11/09/imam-anwar-al-awlaki-calls-hasan-hero.aspx.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "American al-Qaida Spokesman Lauds Fort Hood Killer". The New York Times. March 7, 2010. Retrieved March 7, 2010.

- ^ a b "Investigation Continues Into Fort Hood Shooting". FBI. November 11, 2009. Retrieved November 12, 2009.

- ^ Roupenian, Elisa (November 9, 2009). "Retired Colonel to Defend Accused Fort Hood Shooter". Retrieved Nov. 9, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Independent Online. "Fort Hood suspect refuses to talk". Iol.co.za. Retrieved November 12, 2009.

- ^

Valentino Lucio (February 13, 2010). "Hearing date for Hasan delayed". San Antonio Express. Retrieved February 13, 2010.

Col. James Pohl, the investigative officer assigned to the case, granted a request from the defense to delay the start of the hearing, which was originally set for March 1. Pohl served on a Guantanamo military commission and oversaw the case of U.S. troops charged in the Abu Ghraib prison scandal.

- ^ "Investigators say Fort Hood suspect acted alone". Associated Press. Novemberr 9, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)"a separate investigation revealed Hasan's communications with another individual they declined to identify. Separately, another U.S. official said the person Hasan was communicating with was Anwar al-Awlaki" - ^ "Hasan's Computer Reveals No Terror Ties," KNX 1070, November 9, 2009

- ^ a b Yochi j. dreazen (November 9, 2009). "Shooter Likely Acted Alone". Wall Street Journal.

- ^ a b Johnston, David (November 9, 2009). "U.S. Knew of Suspect's Tie to Radical Cleric". New York Times. Retrieved January 8, 2010.

- ^ Thu 1:21 pm ET (November 12, 2009). "Army: Fort Hood suspect charged with murder". Yahoo! News. Retrieved November 12, 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Nancy Montgomery. "Calls for 14th murder count in Fort Hood case". Stars and Stripes. Retrieved December 4, 2009.

- ^ "Case against Fort Hood suspect faces many hurdles". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved November 10, 2009.

- ^ a b "Who should try Nidal Malik Hasan – military or federal courts?". Los Angeles Times. November 9, 2009. Retrieved November 10, 2009.

- ^ Death penalty rare, executions rarer in military[dead link]

- ^ "The U.S. Military Death Penalty | Death Penalty Information Center". Deathpenaltyinfo.org. Retrieved November 21, 2009.

- ^ "60% Want Fort Hood Shooting Investigated as Terrorist Act – Rasmussen Reports™". Rasmussenreports.com. Retrieved November 12, 2009.

- ^ Ex-F.B.I. Director to Examine Ft. Hood; the New York Times, published and retrieved on December 8, 2009.

- ^ "Pentagon Report on Fort Hood Details Failures". New York Times. January 15, 2010.

- ^ a b Thompson, Mark (January 20, 2010). "Fort Hood Report: No Mention of Islam, Hasan Not Named". TIME. Retrieved February 5, 2010.

- ^ Corum, James (January 21, 2010). "Pentagon report on Fort Hood is a travesty that doesn't even mention Islam – Telegraph Blogs". Blogs.telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved February 5, 2010.

- ^ "GOP Congressman Blasts Pentagon Report on Fort Hood Shooting". FOXNews.com. Retrieved February 5, 2010.

- ^ Saunders, Debra J., "Political correctness on Fort Hood at Pentagon, San Francisco Chronicle, January 25, 2010, January 25, 2010

- ^ U.S. torn over whether some Islamists offer insight or pose threat

- ^ Bender, Brian. "Ft. Hood suspect was Army dilemma". Boston Globe. Retrieved February 23, 2010.

<references> tag (see the help page).External links

- Fort Hood official U.S. Army website

- Fort Hood Sentinel Fort Hood newspaper

- Fort Hood Shootings ongoing coverage from CNN

- Fort Hood Army Base (Texas) and Nidal Malik Hasan ongoing coverage from The New York Times

- Shootings at Fort Hood ongoing coverage from The Washington Post

- Presentation on Islam by Nidal Malik Hasan (Washington Post website)

- Shooting Spree at Fort Hood – image slideshow by Life magazine

31°8′33″N 97°47′47″W / 31.14250°N 97.79639°W