Manchuria

| Manchuria | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Extent of Manchuria according to:

Definition 1 (dark red) Dark Red Medium Red Light Red | |||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 滿洲 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 满洲 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Mongolian name | |||||||||||

| Mongolian Cyrillic | Манж | ||||||||||

| Manchu name | |||||||||||

| Manchu script | |||||||||||

| Russian name | |||||||||||

| Russian | Маньчжурия | ||||||||||

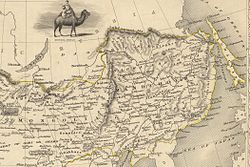

Manchuria is a historical name given to a vast geographic region in northeast Asia. Depending on the definition of its extent, Manchuria either falls entirely within People's Republic of China, or is divided between China and Russia. The region is commonly referred to as Northeast China (simplified Chinese: 东北; traditional Chinese: 東北; pinyin: Dōngběi), and historically referred as Guandong (simplified Chinese: 关东; traditional Chinese: 關東; pinyin: guāndōng), which literally means "East of the (Shanhaiguan) Pass/Mountain".

This region is the traditional homeland of the Xianbei (simplified Chinese: 鲜卑; traditional Chinese: 鮮卑), Khitan (Chinese: 契丹), and Jurchen (Chinese: 女真), who built several dynasties in northern China. The region is also the home of the Manchus, after whom Manchuria is named.

Extent of Manchuria

Manchuria can refer to any one of several regions of various size. These are, from smallest to largest:

- Inner Manchuria: Northeast China (Heilongjiang, Jilin and Liaoning) and part of northeastern Inner Mongolia;

- The above, plus the Jehol region of Hebei province;

- The above, plus Outer Manchuria (Russian Manchuria), (from the Amur and Ussuri rivers to the Stanovoy Mountains and the Sea of Japan). Russian Far East comprises Primorsky Krai, southern Khabarovsk Krai, the Jewish Autonomous Oblast and Amur Oblast. These were part of Manchu China according to the Treaty of Nerchinsk of 1689, but were ceded to Russia by the Treaty of Aigun (1858)

- The above, plus Sakhalin Oblast, which is generally included on Chinese maps as part of Outer Manchuria, even though it is not explicitly mentioned in the Treaty of Nerchinsk.

Origin of the name

Manchuria is a translation of the Manchu word Mianju (Chinese language: Mǎnzhōu). This name was used in Chinese documents until the early 20th century, when Manchuria was converted into three provinces by the late Qing government. Since then, the "Three Northeast Provinces" (東三省) was officially used by the Qing government in China to refer to this region, and the post of Viceroy of Three Northeast Provinces (東三省總督) was established to take charge of these provinces. After the 1911 revolution, which resulted in the collapse of the Manchu-established Qing Dynasty, the name of the region where the Manchus originated was known as the Northeast in official documents in the newly-founded Republic of China, in addition to the "Three Northeast Provinces".

In current Chinese parlance, an inhabitant of "the Northeast", or Northeast China, is a "Northeasterner" (Dōng-běi-rén). "The Northeast" is a term that denotes the entire region, encompassing its history, culture, traditions, dialects, cuisines and so forth, as well as the "Three Northeast Provinces" (東三省), which replaced the concept of "Manchuria" in the early 20th century. Though geographically also located in the northeastern part of China, other provinces such as Hebei are not considered to be a part of "the Northeast".

Geography and climate

Manchuria consists primarily of the northern side of the funnel-shaped North China Craton, a large area of highly tilled and overlaid Precambrian rocks. The North China Craton was an independent continent prior to the Triassic period, and is known to have been the northernmost piece of land in the world during the Carboniferous. The Khingan Mountains in the west are a Jurassic[2] mountain range formed by the collision of the North China Craton with the Siberian Craton, which marked the final stage of the formation of the supercontinent Pangaea.

Although no part of Manchuria was glaciated during the Quaternary, the surface geology of most of the lower-lying and more fertile parts of the region consists of extremely deep layers of loess, which have been formed by the wind-born movement of dust and till particles formed in glaciated parts of the Himalayas, Kunlun Shan and Tien Shan, as well as the Gobi and Taklamakan Deserts.[3] Soils are mostly fertile Mollisols and Fluvents, except in the more mountainous parts where they are poorly developed Orthents, as well as the extreme north where permafrost occurs and Orthels dominate.[4]

The climate of Manchuria has extreme seasonal contrasts, ranging from humid, almost tropical heat in the summer to windy, dry, Arctic cold in the winter. This extreme character occurs because the position of Manchuria on the boundary between the great Eurasian continental landmass and the huge Pacific Ocean causes complete monsoonal wind reversal.

In the summer, when the land heats up faster than the ocean, low pressure forms over Asia and warm, moist south to southeasterly winds bring heavy, thundery rain, yielding annual rainfall ranging from 400 mm (16 in.), or less in the west, to over 1150 mm (45 in.) in the Changbai Mountains.[5] Temperatures in the summer are very warm to hot, with July average maxima ranging from 31°C (88°F) in the south to 24°C (75°F) in the extreme north.[6] Except in the far north near the Amur River, high humidity causes major discomfort at this time of year.

In the winter, however, the vast Siberian High causes very cold, north to northwesterly winds that bring temperatures as low as −5°C (23°F) in the extreme south and −30°C (−22°F) in the north,[7] where the zone of discontinuous permafrost reaches northern Heilongjiang. However, because the winds from Siberia are exceedingly dry, snow falls only on a few days every winter and it is never heavy. This explains why, whereas corresponding latitudes of North America were fully glaciated during glacial periods of the Quaternary, Manchuria, though equally cold, always remained too dry to form glaciers[8] – a state of affairs enhanced by stronger westerly winds from the surface of the ice sheet in Europe.

| History of Manchuria |

|---|

|

History

Prehistory

Neolithic sites located in the region of Manchuria are represented by the Xinglongwa culture, Xinle culture and Hongshan culture.

Early history

Manchuria was the homeland of several nomadic tribes, including the Manchu, Ulchs and Hezhen (also known as the Goldi and Nanai). Various ethnic groups and their respective kingdoms, including the Gojoseon, Sushen, Donghu, Buyeo, Goguryeo, Xianbei, Wuhuan, Mohe, Balhae, Khitan and Jurchens have risen to power in Manchuria. At various times in this time period, Han Dynasty, Cao Wei Dynasty, Western Jin Dynasty, Tang Dynasty and some other minor kingdoms of China occupied significant parts of Manchuria.

Manchuria under the Liao and Jin

With the Song Dynasty to the south, the Khitan people of Western Manchuria, who probably spoke a language related to the Mongolic languages, created the Liao Empire in the region, which went on to control adjacent parts of Northern China as well.

In the early 12th century the Tungusic Jurchen people (the ancestors of the later Manchu people) originally lived in the forests in the eastern borderlands of the Laio Empire, and were Liao's tributaries, overthrew the Liao and formed the Jin Dynasty (1115–1234), which went on to control parts of Northern China and Mongolia. Most of the surviving Khitan either assimilated into the bulk of the Han Chinese and Jurchen population, or moved to Central Asia; however, it is thought that the Daur people, still living in northern Manchuria, are also descendants of the Khitans.[9]

The first Jin capital, Shangjing, located on the Ashi River not far from modern Harbin, was originally not much more than the city of tents, but in 1124 the second Jin emperor Wuqimai starting a major construction project, having his Chinese chief architect, Lu Yanlun, build a new city at this site, emulating, on a smaller scale, the Northern Song capital Bianjing (Kaifeng).[10] When Bianjing fell to Jin troops in 1127, thousands of captured Song aristocrats (including the two Song emperors), scholars, craftsmen and entertainers, along with the treasures of the Song capital, were all taken to Shangjing (the Upper Capital) by the winners.[10] Although the Jurchen ruler Wanyan Liang, spurred on by his aspirations to become the ruler of all China, moved the Jin capital from Shangjing to Yanjing (now Beijing) in 1153,[11] and had the Shangjing palaces destroyed in 1157,[11] the city regained a degree of significance under Wanyan Liang's successor, Emperor Shizong, who enjoyed visiting the region to get in touch with his Jurchen roots.[12]

In 1234, the Jin Dynasty fell to the Mongols.

Manchuria under the Mongol Empire

In 1211, after the conquest of Western Xia, Genghis Khan mobilized an army to conquer the Jin Dynasty. His general Jebe and brother Qasar were ordered to reduce the Jurchen cities in Manchuria.[13] They successfully destroyed the Jin forts there. The Khitans under Yelü Liuge declared their allegiance to Genghis Khan and established nominally autonomous state in Manchuria in 1213. However, the Jin forces dispatched a punitive expedition against them. Jebe went there again and the Mongols pushed out the Jins.

The Jin general, Puxian Wannu, rebelled against the Jin Dynasty and founded the Dazhen (大眞) kingdom in Dongjing (Liaoyang) in 1215. He assumed the title Tianwang (天王 lit. Heavenly King) and the era name Tiantai (天泰). Puxian Wannu allied with the Mongols in order to secure his position. However, he revolted in 1222 after that and fled to an island while the Mongol army invaded Liaoxi, Liaodong and Khorazm. As a result of an internal strife among the Khitans, they failed to accept Yelü Liuge's rule and revolted against the Mongol Empire. Fearing of the Mongol pressure, those Khitans fled to Goryeo without permission. But they were defeated by the Mongol-Korean alliance. Genghis Khan (1206–1227) gave his brothers and Muqali Chinese districts in Manchuria.

The Great Khan Ogedei's son Guyuk crushed Puxian Wannu's dynasty in 1233, pacifying southern Manchuria. Some time after 1234 Ogedei also subdued the Water Tatars in northern part of the region and began to receive falcons, harems and furs as taxation. The Mongols suppressed the Water Tatar-rebellion in 1237. In Manchuria and Siberia, the Mongols used dogsled relays for their yam. The capital city Karakorum directly controlled Manchuria until the 1260s.[14]

The Great Khan Kublai renamed his empire "Great Yuan" in 1271, instead of the old title-"Ikh Mongol Uls".[15] Under the Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368), Manchuria was divided into Liaoyang and Zhendong districts. Descendants of Genghis Khan's brothers such as Belgutei and Qasar ruled the area under the Great Khans.[16] The Mongols eagerly adopted new artillery and technologies. The world's earliest known cannon, dated 1282, was found in Mongol-held Manchuria.[17]

After the expulsion of the Mongols from China, the Jurchen clans remained loyal to the Mongol Khagan Toghan Temur. In 1375, Nahacu, a Mongol official of the Northern Yuan in Liaoyang province invaded Liaodong with aims of restoring the Mongols to power. Although he continued to hold southern Manchuria, Nahacu finally surrendered to the Ming Dynasty in 1387. In order to protect the northern border areas the Ming decided to "pacify" the Jurchens in order to deal with its problems with Yuan remnants along its northern border. The Ming solidified control only under Yongle Emperor (1402–1424).

Manchuria during the Ming Dynasty

The Ming Empire took control of Liaoning in 1371, just three years after the expulsion of the Mongols from Beijing. During the reign of the Yongle Emperor in the early 15th century, efforts were made to expand Chinese control throughout entire Manchuria. Mighty river fleets were built in Jilin City, and sailed several times between 1409 and ca. 1432, commanded by the eunuch Yishiha down the Sungari and the Amur all the way to the mouth of the Amur, getting the chieftains of the local tribes to swear allegiance to the Ming rulers.[18]

Soon after the death of the Yongle Emperor the expansion policy of the Ming was replaced with that of retrenchment in southern Manchuria (Liaodong). Around 1442, a defence wall was constructed to defend the northwestern frontier of Liaodong from a potential threat from the Jurched-Mongol Oriyanghan. In 1467-68 the wall was expanded to protect the region from the northeast as well, against attacks from Jianzhou Jurchens. Although similar in purpose to the Great Wall of China, this "Liaodong Wall" was of a simpler design. While stones and tiles were used in some parts, most of the wall was in fact simply an earthen dike with moats on both sides.[19]

Starting in the 1580s, a Jianzhou Jurchens chieftain Nurhaci (1558–1626), originally based in the Hurha River valley northeast of the Ming Liaodong Wall, started to unify Jurchen tribes of the region. Over the next several decades, the Jurchen (later to be called Manchu), took control over most of Manchuria, the cities of the Ming Liaodong falling to the Jurchen one after another. In 1616, Nurhaci declared himself a khan, and founded the Later Jin Dynasty (which his successors renamed in 1636 to Qing Dynasty).

Manchuria within the Qing Dynasty

In 1644, the Manchus took Beijing, overthrowing the Ming Dynasty and soon established the Qing Dynasty rule (1644–1912) over all of China.

To the south, the region was separated from China proper by the Inner Willow Palisade, a ditch and embankment planted with willows intended to restrict the movement of the Han Chinese into Manchuria during the Qing Dynasty, as the area was off-limits to the Han until the Qing started colonising the area with them later on in the dynasty's rule. This movement of the Han Chinese to Manchuria is called Chuang Guandong. The Manchu area was still separated from modern-day Inner Mongolia by the Outer Willow Palisade, which kept the Manchu and the Mongols in the area separate.

Loss of the "Outer Manchuria"

To the north, the boundary with Russian Siberia was fixed by the Treaty of Nerchinsk (1689) as running along the watershed of the Stanovoy Mountains. South of the Stanovoy Mountains, the basin of the Amur and its tributaries belonged to the Manchu Empire. North of the Stanovoy Mountains, the Uda Valley and Siberia belonged to the Russian Empire. In 1858, a weakening Manchu China was forced to cede Manchuria north of the Amur to Russia under the Treaty of Aigun; however, Qing subjects were allowed to continue to reside, under the Qing authority, in a small region on the now-Russian side of the river, known as the Sixty-Four Villages East of the Heilongjiang River.

In 1860, at the Treaty of Peking, the Russians managed to extort a further large slice of Manchuria, east of the Ussuri River.

As a result, Manchuria was divided into a Russian half known as “Outer Manchuria”, and a remaining Chinese half known as “Inner Manchuria”. In modern literature, “Manchuria” usually refers to Inner (Chinese) Manchuria. (cf. Inner and Outer Mongolia). As a result of the Treaties of Aigun and Peking, China lost access to the Sea of Japan.

Forty years later, during the Boxer Rebellion, Russian soldiers killed ten-thousand Chinese (Manchu, Han Chinese and Daur people) living in Blagoveshchensk and Sixty-Four Villages East of the River.[20][21]

Russian and Japanese encroachment

By the 19th century, Manchu rule had become increasingly sinicized and, along with other borderlands of the Chinese Empire such as Mongolia and Tibet, came under the influence of colonial powers such as Britain which nibbled at Tibet, France at Hainan and Germany at Shandong. Meanwhile the Russia encroached upon Turkestan and Outer Mongolia, having annexed Outer Manchuria.

Inner Manchuria also came under strong Russian influence with the building of the Chinese Eastern Railway through Harbin to Vladivostok. Some poor Korean farmers moved there. In Chuang Guandong many Han farmers, mostly from Shandong peninsula moved there.

Japan replaced Russian influence in the southern half of Inner Manchuria as a result of the Russo-Japanese War in 1904–1905. Most of the southern branch of the Chinese Eastern Railway (the section from Changchun to Port Arthur (Japanese: Ryojun)) was transferred from Russia to Japan, and became the South Manchurian Railway. In this series of historical events, Jiandao (in the region bordering Korea), was handed over to Qing Dynasty as a compensation for the South Manchurian Railway.

Between both world wars (WW1/WW2), Manchuria became a political and military battleground. Japanese influence extended into Outer Manchuria in the wake of the Russian Revolution of 1917, but Outer Manchuria had reverted to Soviet control by 1925. Japan took advantage of the disorder following the Russian Revolution to occupy Outer Manchuria, but Soviet successes and American economic pressure forced Japanese withdrawal.

In the 1920s Harbin was flooded with 100,000 to 200,000 Russian white émigrés fleeing from Russia. Harbin held the largest Russian population outside of the state of Russia (see Harbin Russians).[22][23]

Manchuria was (and still is) an important region for its rich mineral and coal reserves, and its soil is perfect for soy and barley production. For pre-World War II Japan, Manchuria was an essential source of raw materials. Without occupying Manchuria, the Japanese probably could not have carried out their plan for conquest over Southeast Asia or taken the risk to attack Pearl Harbor on the 7th of December, 1941.[24]

Japanese invasion and Manchukuo

Around the time of World War I, Zhang Zuolin established himself as a hugely powerful warlord with influence over most of Manchuria. He was determined to keep his Manchu army under his control and to keep Manchuria free of foreign influence. The Japanese tried to kill him in 1916 by throwing a bomb under his carriage, but failed. The Japanese finally succeeded on June 2, 1928, when a bomb exploded under his seven-carriage train a few miles from Mukden station.[25]

Following the Mukden Incident in 1931 and the subsequent Japanese invasion of Manchuria, Inner Manchuria was proclaimed as an independent state, Manchukuo. The last Manchu emperor, Puyi, was then placed on the throne to lead a Japanese puppet government in the Wei Huang Gong, better known as "Puppet Emperor's Palace". Inner Manchuria was thus formally detached from China by Japan to create a buffer zone to defend Japan from Russia's Southing Strategy and, with Japanese investment and rich natural resources, became an industrial powerhouse. However, under Japanese control Manchuria was one of the most brutally run regions in the world, with a systematic campaign of terror and intimidation against the local Russian and Chinese populations including arrests, organised riots and other forms of subjugation.[26] The Japanese also began a campaign of emigration to Manchukuo; the Japanese population there rose from 240,000 in 1931 to 837,000 in 1939 (the Japanese had a plan to bring in 5 million Japanese settlers into Manchukuo).[27] Hundreds of Manchu farmers were evicted and their farms given to Japanese immigrant families.[28] Manchukuo was used as a base to invade the rest of China, an action that was very costly to Japan in terms of the damage to men, matériel and political integrity.

At the end of the 1930s, Manchuria was a trouble spot with Japan clashing twice with the Soviet Union. These clashes - at Lake Khasan in 1938 and at Khalkhin Gol one year later - resulted in many Japanese casualties. The Soviet Union won these two battles and a peace agreement was signed. However, the regional unrest endured.[29]

After World War II

After the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, Japan in 1945, the Soviet Union invaded from Soviet Outer Manchuria as part of its declaration of war against Japan. From 1945 to 1948, Inner Manchuria was a base area for the Chinese People's Liberation Army in the Chinese Civil War. With the encouragement of the Soviet Union, Manchuria was used as a staging ground during the Chinese Civil War for the Communist Party of China, which emerged victorious in 1949.

During the Korean War of the 1950s, 300,000 soldiers of the Chinese People's Liberation Army crossed the Sino-Korean border from Manchuria to repulse UN forces led by the United States from North Korea.

In the 1960s, Manchuria's border with the Soviet Union became the site of the most serious tension between the Soviet Union and China. The treaties of 1858 and 1860, which ceded territory north of the Amur, were ambiguous as to which course of the river was the boundary. This ambiguity led to dispute over the political status of several islands. This led to armed conflict in 1969, called the Sino-Soviet border conflict.

With the end of the Cold War, this boundary issue was discussed through negotiations. In 2004, Russia agreed to transfer Yinlong Island and one half of Heixiazi Island to China, ending a long-standing border dispute. Both islands are found at the confluence of the Amur and Ussuri Rivers, and were until then administered by Russia and claimed by China. The event was meant to foster feelings of reconciliation and cooperation between the two countries by their leaders, but it has also sparked different degrees of discontent on both sides. Russians, especially Cossack farmers of Khabarovsk, who would lose their ploughlands on the islands, were unhappy about the apparent loss of territory. Meanwhile, some Chinese have criticised the treaty as an official acknowledgement of the legitimacy of Russian rule over Outer Manchuria, which was ceded by the Qing Dynasty to Imperial Russia under a series of Unequal Treaties, which included the Treaty of Aigun in 1858 and the Convention of Peking in 1860, in order to exchange exclusive usage of Russia's rich oil resources. As a result of these criticisms, news and information regarding the border treaty were censored[citation needed] in mainland China by the PRC government. The transfer was carried out on October 14, 2008.[30]

See also

References

- ^ E.g. Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society, Volumes 11-12, 1867, p. 162

- ^ Bogatikov, Oleg Alekseevich; Magmatism and Geodynamics: Terrestrial Magmatism throughout the Earth's History ; pp. 150-151. ISBN 905699168X

- ^ Kropotkin, Prince P.; "Geology and Geo-Botany of Asia"; in Popular Science, May 1904; pp. 68-69

- ^ Juo, A. S. R. and Franzlübbers, Kathrin Tropical Soils: Properties and Management for Sustainable Agriculture; pp. 118-119; ISBN 0195115988

- ^ "Average Annual Precipitation in China". Retrieved 2010-05-18.

- ^ Kaisha, Tesudo Kabushiki and Manshi, Minami; Manchuria: Land of Opportunities; pp. 1-2. ISBN 1110977603

- ^ Kaisha and Manshi; Manchuria; pp. 1-2

- ^ Earth History 2001 (page 15)

- ^ "DNA Match Solves Ancient Mystery". China.org.cn. Retrieved 2010-05-18.

- ^ a b Jing-shen Tao, The Jurchen in Twelfth Century China. University of Washington Press, 1976, ISBN 0-295-95514-7. Pages 28-32.

- ^ a b Tao, p.44

- ^ Tao (1976). Chapter 6. "The Jurchen Movement for Revival", Pages 78-79.

- ^ Tom Shanley- Dominion: Dawn of the Mongol Empire, p.144

- ^ C.P.Atwood-Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire, see: Manchuria

- ^ Patricia Ann Berger - Empire of emptiness: Buddhist art and political authority in Qing China, p.25

- ^ Niraj Kamal -Arise, Asia!: respond to white peril, p.76

- ^ C.P.Atwood-Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire, p.354

- ^ Shih-shan Henry Tsai, The Eunuchs in the Ming Dynasty. SUNY Press, 1996. ISBN 0791426874. Partial text on Google Books. P. 129-130

- ^ Edmonds, Richard Louis (1985). Northern Frontiers of Qing China and Tokugawa Japan: A Comparative Study of Frontier Policy. University of Chicago, Department of Geography; Research Paper No. 213. pp. 38–40. ISBN 0-89065-118-3.

- ^ "俄军惨屠海兰泡华民五千余人(1900年)". News.163.com. Retrieved 2010-05-18.

- ^ (2008-10-15 16:41:01) (2008-10-15). "江东六十四屯". Blog.sina.com.cn. Retrieved 2010-05-18.

{{cite web}}:|author=has numeric name (help) - ^ "Fleeing Revolution". Neh.gov. Retrieved 2010-05-18.

- ^ The Russians are coming., Economist (US)

- ^ Edward Behr, The Last Emperor, 1987, p. 202

- ^ Edward Behr, ibid, p. 168

- ^ Edward Behr, ibid, p. 202

- ^ "Prasenjit Duara: The New Imperialism and the Post-Colonial Developmental State: Manchukuo in comparative perspective". Japanfocus.org. Retrieved 2010-05-18.

- ^ Edward Behr, ibid, p. 204

- ^ Battlefield - Manchuria

- ^ "Handover of Russian islands to China seen as effective diplomacy | Top Russian news and analysis online | 'RIA Novosti' newswire". En.rian.ru. 2008-10-14. Retrieved 2010-05-18.

Bibliography

- Elliott, Mark C. "The Limits of Tartary: Manchuria in Imperial and National Geographies." Journal of Asian Studies 59, no. 3 (2000): 603-46.

- Jones, Francis Clifford, Manchuria Since 1931, London, Royal Institute of International Affairs, 1949

- Tao, Jing-shen, The Jurchen in Twelfth-Century China. University of Washington Press, 1976, ISBN 0-295-95514-7.