Golden Team

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

No issues specified. Please specify issues, or remove this template. |

The Golden Team (Hungarian: Aranycsapat; also known as the Magical Magyars, the Marvelous Magyars, the Magnificent Magyars, or the Mighty Magyars) refers to the record-breaking and world renowned Hungary national football team of the 1950s held in esteem as one of the greatest national sides ever in international competition. It is praised, among other accomplishments, for being the team that re-invented football in the post-war World War II era. It is associated with several of the most notable matches of all time, taking part in four historically significant games of the 20th century, including the "Match of the Century", the "Battle of Berne", a semi-final with Uruguay and the "Miracle of Berne". Inflicting maiden defeats on world powers England (by a team outside the UK and the Republic of Ireland) and Uruguay, one of the side's last unified actions consigned the Soviet Union to their first ever defeat at home mere weeks before a spontaneous national uprising against the Soviets precipitated the breakup of the side.

The team's brilliance from the spring of 1950 lasted for six years until its partial meltdown after the ill-fated 1956 Hungarian Revolution — a flashpoint in the Cold War and a strikingly heroic and historically consequential event commonly viewed as having rent the first major blow against the shining panoply of the monolithic communist world. It is credited with directly leading to a future tense football that opened a new chapter in the game's tactical scope for positional fluidity, thus rendering contemporary form and styles of the game outmoded. It introduced a powerful revolutionary ground game with its polyvalent quasi-4-2-4 offense and an early approximation towards the famous 360-degree "Total Football" strategy that later the Dutch football scene operated. The immediate heirs to Hungary's 4-2-4 tactical shape were eventual world champions Brazilian teams who adopted, emulated and enriched their legacy for the 1958, 1962 and 1970 World Cups.

One of the most technically superb teams in history, by ratio of victories per game, tactical renovation in company with its acclaimed matches, the side ranks as one of association sports' most dominant forces of the 20th century. As the definitive sporting force from the Eastern Bloc of the era, it was also a tool used by communist authorities in the propaganda war with the Cold War West, being held up as emblematic of socialist ideals by virtue of liberating the genius that lay dormant in the proletariat. Its sporting prominence has not gone unremarked upon by postwar historians who noted its influence on West German political and economic trends, and nationalistic streams of consciousness following one of the most celebrated of World Cup competitions in 1954.

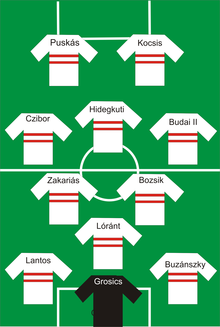

Their ensemble was built around a core talent syndicate of a half-a-dozen world-class players, led by its talismanic captain Ferenc Puskás, prodigal goalscorer Sándor Kocsis, the deep lying center-forward Nándor Hidegkuti, swift and sprightly winger Zoltán Czibor, midfield choreographer József Bozsik who set the tenor for the tactical nous going forward and a first rate goalkeeper, Gyula Grosics. The incomparable attacking nexus of Puskás—Kocsis—Hidegkuti produced throughout their careers a windfall of 198 goals. Mihály Lantos, Gyula Lóránt, József Zakariás and Jenő Buzánszky modelled a praiseworthy and oft-outperforming defense.

The extent of the Magyars' sojourn as the giants of world football has since been unmatched and merits a closer visit of performances. Aside from the controversial 1954 World Cup final match, the team in internationals would suffer no defeats for 6 years, marking 42 victories and 7 draws — a record that lifts the side into the realm of legend. Indeed, under the Elo rating system they achieved the highest rating recorded in history by a national side (2166 points, June 1954). The constant and their essential hard currency was cogent offensive bandwidth within a 50 game period that leavened the sport with an astonishing 215 goals — over 4 goals per game. It was around these games that their truly golden age and supremacy was framed.

Current evidence is mounting and surfacing in the 21st century in a widening scope from within Germany both on the scholarly (University of Leipzig, Oct. 2010) and historical eye witness levels (Switzerland, 2004) giving widely held suspicions credence that the Hungarians' defeat in the 1954 World Cup Final match was referable to West Germany's use of performance-enhancing drugs and uneven refereeing due to the eco-political Zeitgeist of the times.

International Football's All-time Highest Ratings

The following is a list of national football teams ranked by their highest Elo score ever reached as of July 16, 2010.

| Rank | Nation | Points | Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2166 | 30 June 1954 | |

| 2 | 2153 | 17 June 1962 | |

| 3 | 2140 | 11 July 2010 | |

| 4 | 2117 | 3 April 1957 | |

| 5 | 2106 | 15 August 2001 | |

| 6 | 2100 | 6 July 2010 | |

| 7 | 2099 | 4 September 1974 (as West Germany) | |

| 8 | 2079 | 20 July 1939 | |

| 9 | 2046 | 1 September 1974 | |

| 10 | 2041 | 22 October 1966 | |

| 11 | 2035 | 13 June 1928 | |

| 12 | 2023 | 9 October 1983 (as Soviet Union) | |

| 13 | 1999 | 27 June 2004 | |

| 14 | 1998 | 31 May 1934 | |

| 15 | 1983 | 15 November 2000 | |

| 16 | 1967 | 11 July 1998 | |

| 17 | 1962 | 25 June 1998 (as FR Yugoslavia) | |

| 18 | 1960 | 13 June 1986 | |

| 19 | 1953 | 10 March 1888 | |

| 20 | 1950 | 25 June 1950 |

'Socialist Football' and the advent of the "Playmaker"

The source of the intellectual firepower of the team at the managerial level began with Gusztáv Sebes, who had been a trade union organizer in Budapest and pre-war Paris at Renault car factories and thus was accorded a political clean bill of health to run affairs as the Deputy Sports Minister. Coming on with good political connections, he knead his socialist credentials to a new formulaic style that caused world football to witness "socialist football" in its prime — team game that would brush aside an assortment of individuals for six years to set milestones not set before or since. Sebes and his staff were keen to reference a new movement in football governed by the idea that a total cohesive solution with contours of players equally sharing in the ball's propagation were answers to soccer's future. This sketched the foreword and prelude, in a sense, to "Total Football" 20 years before the Dutch, where individual roles in zonal positions should not be strictly defined.

A lasting contribution of importance of the Magyars, especially involved the prototype advent of a crucial player that would put the game on a tactical furthering — the deep lying centre-forward. Into this total sum versatile solution (where players could shift and interplay other positions), Sebes laid his most influential centrepiece — a high value player unveiled for a groundbreaking role that caused Hungary to reform the game forever. Nándor Hidegkuti was set as a deep-lying free trading entrepreneur behind the twin pairing of Puskás and Kocsis, known in football parlance as being "in the hole". This nuance of moving Hidegkuti off the main line put the game on a new course and into football's lexicon entered the fluid station called "playmaker". Opposing lines were un-steadied and pulled apart by this dual-purpose player by drawing a natural response and tendency from defenses leaving him unmarked to operate freely in space un-buffeted by not being amid the forwards. With event-driven spontaneity, Hidegkuti provided crashing sorties as ball movement dictated to crumble the center goal area; and unlocked in the No. 9 position a new autonomous menacing robust character in football operating on the event horizon between midfield and the rearguards and between creator and goalscorer. Hidegkuti has been called the "father of total football" and was an astute navigator with 39 goals in 69 appearances. Thus this triune partnership of Puskás and Kocsis up front with a force-multiplier leveraged in Hidegkuti opened many doors of attack across inflexible defenses to obviate and subordinate most traditional systems.

Goalscorers: Puskás and Kocsis

Certainly the "European Player of the 20th Century" and twice World Player of the Year (1952, 1953), Ferenc Puskás often enters the conversation of where the greatest footballers ought to be lodged in the pantheon of the last 100 years. The ever engaging and personable Ferenc Puskás was the most powerful striker Europe ever produced at 1st division football. He was also the greatest goalscoring international who ever lived. Undoubtedly, the most renowned and greatest of Hungarian sportsmen, he is likely in company with Harry Houdini and Ernő Rubik who lent his name to the iconic Rubik's Cube, for being the most famous Hungarian citizen of the 20th Century.

In a difficult rebuilding world of the postwar era, in the arc light and formative glow of nascent mass media with a global reach and enhanced telecommunications, increasingly networked newswires and live television coverage that meet audiences as never before, Puskás was football's first superstar both club level and in the world game predating the likes of Di Stéfano, Pelé, Johan Cruijff, Diego Maradona, and Zinedine Zidane.

Oft-likened short, he was of modest proportions, rotund with muscular billiard ball table legs and average in-line speed but with deceptive acceleration. Puskás never did acclimate to using his nondominant right foot for much except to dribble and scored few goals with his head. But he more than made up with an on-field generalship and a deep cerebral reading of the game. He had a keen footballing brain to match his otherworldly accuracy. He had intuition with extra sensory perception to soundly grasp other sides' tactical nuances in less than 15 minutes of play by issuing a stream of instructions to orient his team. He exhibited a precocious talent at an early age making the national team all of 18 as a supreme possessor with a capering dribble and heroic scoring indulgence on the ball. He is alleged to have been blessed with the most powerful drive ever cast from a left foot — an exclusive leaden snapshot that deftly tore through defenses with remarkable precision. Much of Hungary's goalscoring largesse as seen by many came by way of Puskás' on-field influence, who scored a record 514 1st division goals and a total sum 1176 goals in a 24-year career. The main producer and inspirer of a great Hungarian squad who charted the team's mantle toward unrivalled heights, Puskás was honored for being named the greatest 1st division goalscorer in the 20th century by the prestigious International Federation of Football History & Statistics (IFFHS) in 1995. Pelé was voted the most outstanding player of the century by the IFFHS with Puskás not far behind, ranking just behind Diego Maradona in the balloting.

A man with a touch of Midas in him, every team to which Puskás was attached as a captain and player were eminently the best in the world that seemed to prosper immensely from his seniority; profiting from an elegant yet fiery competitor with the sunniest of rough-diamond manners and a loud style who could seem to annex the most obdurate lines with brilliant expositions that sparkled nigh on goal. As captain of mighty Honvéd (for whom the majority of the national team's players played at club level), the greatest club side before the emergence of Real Madrid, and captain of Hungary, he was paired with the formidably talented and his near equal Sándor Kocsis that blossomed into an almost symbiotic partnership. Theirs was a story of two invincible heroes in their prime playing to huge crowds who always seemed to move inexorably towards goal to drive in balls from all possible angles and distances. They were the greatest redoubtable scoring tandem who ever graced world football with 159 goals between them, vastly outdistancing all those that came before to put in place records that would be everlasting.

Later estranged from his homeland for many a good reason, but due in part, to the reprisals that were the fallout of the failed Hungarian Revolution and what might have awaited him for his refusal to return from abroad, the unusually apolitical Puskás was adrift in exile. On the wrong side of 30 and serving a one-year ban from FIFA, the man of large and joyous appetites and a heart spent on goodwill, was now out of shape and thought to be in the twilight of his playing days. Soon he found himself in the employ of the greatest club side in the world, Real Madrid at the height of its powers, to begin a second consecutive and stunning double career.

At a time when players think of retirement, Puskás faced a daunting challenge of learning a new language in the distinct new world of Francisco Franco's Spain, but with the gift of confidence and the right mental attitude too, Puskás soon endeared himself to everyone around him. Most importantly, he gelled with on-field boss and great Argentine star Alfredo Di Stéfano, who was never the easiest man to know, temperamental cheek being part of his charm. Winning 5 Spanish championships along with way, Puskás again became a relevation, a four-time Spanish league-leading incandescent forward in legendary communion with Di Stéfano to form the basis for the greatest double act (as had been the earlier case with Kocsis) world club football has ever seen. While at Read Madrid, Puskás was considered the indispensable man of campaigns that saw Real Madrid win three UEFA European Championships and enlisted his help to be finalists on two other occasions.

As a player who was never bought or sold in his life, Puskás spent his entire career at the very top of his profession that seemed to raise his game to a sublime level. Puskás was central to the very heart of football history itself, being involved in three of the most discussed matches of all-time: the "Match of the Century (where he scored twice), "Miracle of Berne" (the 1954 World Cup Final, where he scored once and had a picture perfect 87th minute poignant equalizer unpardonably called offside), and Eintracht Frankfurt 3 vs. Real Madrid 7 (the 1960 European Cup Final where he scored 4 goals in what has been called the greatest and most famous European club match in history). Puskás' count of 84 international goals in 85 games still is football's benchmark, unmatched by any top-flight player from the Americas, Europe, Australia, and Africa.

After the 1956 Uprising there were pockets of Hungarian expatriates in every major city in the West. While traveling with Real Madrid and beyond, he became a veritable consulate for members of these communities, ready to lend his support, financial or otherwise, to those who were in most need. Therein lies a Horatio Alger tale of a charitable man and player rising to the pinnacle of the game that began behind the Iron Curtain.

Current FIFA President Sepp Blatter had seen Puskás play in the 1954 FIFA World Cup Final in Berne. As a 18 year old Swiss journalist, Blatter was emotionally involved throughout the match as a proud fan of the Magical Magyars. In homage to Puskás for what he represented on the field and for enduring personal virtues off of it, Blatter in 2009 founded an international award meant to ensure Puskás' memory for future generation of footballers. The annual FIFA Puskás Award is presented at the FIFA World Player of the Year Gala and is the only FIFA award named after a former player.

Many years before the team's arrival on the world scene, Hungary's Imre Schlosser merited high citation for gaining the most international goals with 59 since 1921. During when the Mighty Magyars were very much in flower, Puskás proceeded to famously break his countryman's world record in 1953, and Sándor Kocsis put on record his 60th goal in just his 50th game in 1955. Hungary boasted of playing host to the No. 1 and No. 2 world record holders in unison on the pitch. Kocsis was an exceptionally good footballer whose playing career at home and abroad ran almost in parallel with Puskás'. Kocsis was an authority in size, pace and note must be taken that his aerial prowess the world would come to see had no peer. Aside the peerless Puskás, the only 20th century player to outrank Kocsis's 75 goals and world record 6 hat tricks was the Brazilian Pelé — whose name advertised his renown. Kocsis' pervasive quality at point and aura was unavoidable. As the number two striver of breadwinning scores, he mystified backfields with stunning alacrity. Defenders were put on notice every time he touched the ball.

Top Goalscorers at the close of the 20th Century (Dec. 1999)

| Pos. | Player | Nation | Goals Scored | Games Played | Years Active |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Ferenc Puskás | Hungary |

84 goals | 85 internationals | 1945–1956 |

| 2. | Pelé | Brazil |

77 goals | 92 internationals | 1957–1971 |

| 3. | Sándor Kocsis | Hungary |

75 goals | 68 internationals | 1948–1956 |

| 4. | Gerd Müller | 68 goals | 62 internationals | 1966–1974 | |

| 5. | Hussein Saeed | 63 goals | 126 internationals | 1976–1990 | |

| 6. | Imre Schlosser | Hungary |

59 goals | 68 internationals | 1906–1927 |

Source: http://rsssf.com/miscellaneous/century.html#goals

1952 Olympic Games (Yugoslavia vs. Hungary)

The Hungarians arrived to the 1952 Summer Olympics to audition their command of the game in a grade that posed plenty already. In a little over 2 years unbeaten, their last 15 opponents were overlabored by 5.27 goals-per-game as most sides were wholly overwhelmed by the players astride the Danube. Scorelines of 5-0 and 6-0 were commonly seen and only a single team had defeated them in their 19 prior matches while victorious in 15. News traveled along the footballing grapewine that a vibrant, skillful and determined team's star from Central Europe was rising fast.

Already well established was one of Europe's premier sides, warm press by the international news media gave Hungary high visibility outside the Iron Curtain to project a brand that the world at large had not yet seen. There great reputations were first achieved, and the highly entertaining men's football tournament proved to be a preview of coming attractions. With a mercurial corps that was adventurous in attack featuring Puskás, Kocsis, and 'super-sub' Péter Palotás the team progressed through the field in a five-game attacking exposition scoring 20 goals. Those facing them could but tread lightly on their gapless blunting defense that conceded only 2.

Meeting them squarely in the Semi-Final were the 1948 defending Olympic champions, a Swedish team heavily laden with talent, generally capable of practicing the game skillfully. In a performance highly rated as one of their finest, a Ferenc Puskás first minute goal was the primer to a thoroughly emphatic game that served positive notice to the most influential circles in the European football community. Their 6-0 victory was of outgoing quality, and resonated most well with one especially. Tracking developments and viewing events on the field was Stanley Rous, secretary general of the English Football Association and future FIFA President, who praised his counterpart and extended a future invitation to oblige the Hungarians in Empire Wembley Stadium in England.

Placed before them in the championship Final in front of 60,000 in Helsinki Olympic Stadium were the world's No. 7 team — their neighbors to the south, with whom the Hungarian communist dictatorship on ideological grounds had strained relations. Yugoslavia had maneuvered into a tradition and position that was largely independent of Moscow. The 1948 Olympic finalist Yugoslavian squad wore the makings of an emerging tier-one global player, the game's meaning all the more inspired and informed by the intersection of politics and sport. It was the day of the match that manager Gusztáv Sebes was beforehand politically instructed not to lose. The match against the Yugoslavs was duly hard fought. Of the many foreign correspondents writing of the tournament was a young Spanish reporter who covered the Hungarian team. He was no less than Juan Antonio Samaranch. Then penning for a Spanish daily, Samaranch was later to become one of the century's most recognizable public spirits who cut a grandiose figure in the Olympic movement as the future President of the International Olympic Committee (1980–2001), and self-described enthusiast of the Hungarians' élan.

Late in the game, the Yugoslav backline was penetrated by Ferenc Puskás in the 70th minute, who nonchalantly put a short grounder past two onsetting defenders before goal, and winger Zoltán Czibor broke off from a direct line of action at flank with a supportive goal at the 88th minute. Their 2-0 victory signaled their trajectory from a continental to that of a world power, and the sobriquet "The Golden Team" first became a popular term of endearment back in Budapest.

The triumph of the Golden Team on a patch of green grass, where joyous life and great freedom flourished to imitate art, was but a subset of a remarkable larger than life story of pushing the limits of human possibilities. Coincidentally, the 1952 Summer Olympics provided a brief and reliable uplifting interlude of joy and pride for a small resilient nation of just over 9 and a half million seven years apart from the devastation and displacement of World War II before passing into the maws and orbit of a communist police state and into a highly restrictive society. Biding defiance to very long odds, Hungary compiled an amazing Olympic record of managing to finish 3rd in the medals table behind the vastly more prodigious United States and the USSR, earning 16 gold medals along with way with a total count of 42 of all colors. It underscored how much special importance the regime was willing to attach to a full commitment of sporting excellence and the political capital that it would confer.

| 1 | 40 | 19 | 17 | 76 | |

| 2 | 22 | 30 | 19 | 71 | |

| 3 | 16 | 10 | 16 | 42 | |

| 4 | 12 | 13 | 10 | 35 | |

| 5 | 8 | 9 | 4 | 21 | |

| 6 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 13 | |

| 7 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 18 | |

| 8 | 6 | 3 | 13 | 22 | |

| 9 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 11 | |

| 10 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 5 |

Central European Championship (Italy vs. Hungary 1953)

During this era, Hungary also partook in the Central European International Cup, a nations cup for teams from Central Europe and forerunner of the pan-European European championship. The competing field included Austria, Czechoslovakia, Italy and Switzerland. After 5 years in production the 5th tournament culminated in a highly prized match between Hungary and a powerful Italian team.

Italy was, in many ways, the frontier and nursery for early European continental footballing ideas. In the 1930s rapid developments were made to be at the center of all that was successful in European football. Italy reached the game's exalted summit by gaining two World Cup honors consecutively in 1934 and 1938 (where Italy defeated Hungary 4-2 in the title game). The Italians were used to thinking seriously about the game and were partial to cultivating and nurturing defensive balance. Italian football was virtually the anti-pole to the offense-based polarity of the Hungarian temperament that viewed themselves as natural attackers. Indeed, one of their key contributions to the game had been proactive in modeling a highly organized backline that was intended to prevent goals. Europe's only enjoyer of World Cup success bestrode the Continent with one of the planet's hectoring untrodden defenses that played to a very high standard at home. It was thought to be more than a match for those that traveled to meet them.

Italy's chosen style for stopping the wherewithal of opposing teams of foreign players, no matter how talented, from drawing good definition on their goal have been written about to give it credence. Outside a single notable defeat to England in 1948, the Azzurri had not competitively suffered a home defeat since days of Benito Mussolini in 1934. They never surrendered more than 2 goals into their net in 36 home internationals and wore a perfect undefeated record to impose an onus and load visitors with care. Behind their only defeat to the English, the Italians furthered their senior squad that only 1 or less goals were allowed against their renowned backline in any home match that impress one the most. Hungary journeyed to Rome and toward a foreign ambiance to play in the inaugural of Rome's newly re-designed famous Stadio Olimpico that presented itself as a dauntingly magnificent fortress of grandeur. Such a marvelous attacking presence posed by Hungary in the eyes of the Italians demanded conquering.

After opening ceremonies, a partisan audience of 90,000 were given perspective that put in relief the contrasting vision between the two teams: between Italy's garrisoned expression presumably the world's top defensive unit contra the world's best frontline and Hungary's fluid and rhythmic carriage belying artfully crafted guile. The football world would see a irresistible Olympian force about to march against the immovable object — mere glimpses into the "Match of the Century".

The men of Italian football arrived in earnest with their reputed defensive superiority as had been known and the outcome was defined on a hard compound of defensive ardor. By the later edge of the first half, the élan of the Hungarian front gainfully accosting the Azzurri defense began to stylistically unlimber it by a dialogue of passing from midfield to coax out the main Italian line exposing their rear to the rewardingly cast deep ball. A Nándor Hidegkuti goal at the 41st minute, and later two strong scores by Puskás in the second half, one a particularly telling late left-footed straight line drive from the top of the penalty box past the unbelief of keeper Lucidio Sentimenti sealed memorable proceedings 3-0 in what was no standard achievement.

So irrepressible was Puskás not only to win, that while leading 2-0 late in the game, he exhorted his teammates for continued attacks and keeper Gyula Grosics to give him the ball at every opportunity. His attitude delighted Italian fans who though much of the wonderful football efforts they just witnessed. Respectful ovation descended on the Hungarian heroes, who were cheered off the field as victors of the tournament.

"Match of the Century" (England vs. Hungary 1953)

Background

A match was arranged later that November in 1953 that would have game-changing implications to prevail upon old insular normative and complacent beliefs to inspire football theory onward. It would precipitate a re-shaping of new core footballing ideas and displace minimally for half a generation football's center of gravity. To occur was an immensely fancied collision between the era's contemporary masters — the Magical Magyars and the venerable aristocrats of the game.

Ten days before their appointment in the ancestral mecca of football, they played a good Swedish team in Budapest in a game that did not give rise to much confidence heading into the biggest match of their lives. Puskás missed from the penalty spot and hit the post, and the Swedes drew level in the 87th minute to earn a 2-2 draw. They were likewise sorted out and pilloried by the press and fans, but the result was ample for the squad to forge past a 19th century 1888-year Scottish record of being undefeated in 22 international matches.

The English had invented the modern game in last half of the 19th century. Its first laws and rules patented by a solicitor by trade Ebenezer Cobb Morley, and soon grew immensely popular across all spectrum of society due to its simple rules and minimal equipment requirements; being globalized as the world's most popular association sport in the last decades of the 19th century and early 20th centuries.

Since the codification of football in 1863 in Victorian England, the English national team had never suffered defeat on its home shores from foreign opposition from outside the British Isles, and their successful tradition had been penultimate and globally decisive. The old producers of football had turned aside every effort in 90 years to overcome the mightiest team of them all. This proud long reign of invincibility knit to semi-mythology was legendary, embedded into socio-national consciousness and ethos as a redoubt and post to which Englishmen could view with surety and confidence in spite of all forecasts, vicissitudes and the ever-changing times. Gorgeous, wonderful, and victorious English football possessed a feel of unbeatable quality and romantic neo-imperial Victorian inheritance with a direct unbroken connection to the palmiest days of the British Empire.

The British press, in building out the game that lay ahead, galvanized worldwide radio and newsprint audiences naming it the "Match of the Century". A visit towards both teams' theoretical power, the media's remark of the match taking on such significance as "The World Championship Decider" — was a becoming view that was more attractive considering the acme strength of both nations. England was ranked No. 3 in the world with a rating of 1943 points or the No. 2 best team in the Old World (Argentina being ranked No. 2 with 2048 points), Hungary was ranked No. 1 with a rating of 2050* points. The anxiously promising match was ever England's sternest challenge to stem a gathering juggernaut from across the Channel from behind the Iron Curtain that had remained unbeaten for over three and a half years — and in deference to a remarkable tradition, untrampled power in Europe, England would have its place in the sun again as the highly approved side.

England fielded a squad of prestige formed of considerable and legendary power within a time-tested and patently English tactical package (3-2-2-3 i.e. the WM formation) catalyzed at the Arsenal Football Club by gifted publicist and maverick manager Herbert Chapman in reaction to the Offside Law of 1925. It was composed of all the stars of League First Division, some of whom were of world renown and whose reputations were second to none. Two of whom would be later knighted for exceptional services rendered toward national British sport. These included a world-class football maestro, the ageless Sir Stanley Matthews who supplied much aerial and crossing prowess to set up goals where ever he traveled, a much feared powerful centre forward in Stan Mortensen who had scored 22 goals in 24 appearances, Sir Alf Ramsey, a superb defender with special spatial awareness and technique, and their very capable centre-half captain Billy Wright. Wright was the first player in the 20th century to reach 100 appearances for a national side, for whom there is current involvement and modern ongoing push to have knighthood conferred posthumously. At England's order was a very powerful midfield, a quadrangle of four players with an untiring work rate of fetching and carrying the ball up and down the field whom the Hungarians referred to as "the piano-carriers".

This highly successful system mated to a hardy, open, spontaneous and industrial style with its usually high quality personnel, united by a wondrous unmistakable English competitive spirit saw England take on all comers outside the Isles since 1901 and never have the world's finest left England victorious.

Meanwhile the relayed radio broadcast by sports commentator György Szepesi back in Hungary almost brought the entire country to a standstill for a few hours. There had been endless pre-match discussion about the English weather, the English ball, the texture and dimensions of the Wembley pitch, Puskás and Wright, goalkeepers Gil Merrick and Grosics, midfielders Bozsik and Jackie Sewell. Virtually all the nation was engrossed in anticipation. Electrical retailers did good business in loudspeakers and radio amplifiers as big stores, restaurants and shops provided coverage for their staff and customers, informed by notices outside their premises that proudly advertised: We are broadcasting the Match of the Century. At kick-off, bustling city life in Budapest ground to a halt, the streets were deserted, apart from a few places where people congregated in public around a loudspeaker. Cinemas showed films to empty auditoriums, buses and trams stopped with no passengers aboard. In factories shift times were prearranged to finish early. In mines, the scoreline was chalked on the sides of cages that descended into the shafts to relay game developments to coal-faced workers.

The Match

On a foggy Wednesday afternoon on November 25, 1953, in front of 105,000 in Empire Wembley Stadium in London and to millions of worldwide listeners and television viewers The Magical Magyars mesmerized. The tactical mileage and individual skill sets between the two teams were seen and revealed immediately. Within the first minute, the whole English defense experienced variable geometric pressure invented out from midfield as the Magyars' startling attack proved insolvable with a new ground game that made lanes into England's stout stereotypical WM formation and exploited a flaw in their rigid marking system that opened yawning gaps by cleverly drawing defenders out of position. Nándor Hidegkuti could not be subdued. 45 seconds into the match, Hidegkuti ran down a centre seam, sold a feint thereby freezing Harry Johnson, diagonally angled inside and sent a rising 15-yard vector into the upper right corner of the net beyond the lunging mitt of goalkeeper Gil Merrick, quickly 1–0. Throughout the game Hidegkuti was un-markable in a starring role as he haunted the English line mixed with befuddling actions of Ferenc Puskás and the Hungarian line that posed tactical riddles by running interference for one another in interchanging their positions almost clairvoyantly on queue. These events left England in a nonplussed state, most especially centre-half Harry Johnston. Johnson was never assignment true in his dealings with Hungary's No. 9 Hidegkuti, unsure whether to accommodate him man-to-man or play zonally that caused him to be subtly adrift in a kind of no man's land that undid a large part of the English defensive posture.

A well-timed English counter-attack ensued that began in the penalty area. Down field Stan Mortensen released Jackie Sewell who put it past Gyula Grosics to restore order 1–1 at 13 minutes. But Nándor Hidegkuti fatefully scored again off a clearance that was treated poorly; and Ferenc Puskás became the world leader for most international goals via a seven-pass negotiation of the English defense, culminating in what many Hungarians call the "Goal of the Century". Puskás' famous "drag-back" goal imparted on him football immorality captured on film by executing a stunning piece of off-hand ball control from impromptu impulse that is a mainstay on classic highlight footage. It involved Puskás taking up position on the right-hand side of the six-yard box after receiving a less than perfect flat pass from right as Billy Wright barrels down to dispossess the escaping ball that drifts toward the dead-ball line. Puskás reflexively drags back the loose ball with the sole of his boot an instant before the arriving tackle, leaving the English captain finding empty space where the ball had been de-cleated and nearly sprawled on his back. Puskás then pivots to find a ray of daylight between the near post and keeper Gill Merrick. The resultant Puskás cannonball between the crook of Merrick's left arm and the near post was shoehorned in to propel a 3–1 scoreline. Soon following was another Ferenc Puskás score, a deflected József Bozsik free-kick that burrowed into the net. Within 30 minutes the lead had swelled to 4–1, ten minutes of the restart the match's competitive phase was resolved.

In the second half, midfielder József Bozsik encroached a few feet outside the English penalty box and launched the ball airborne with a purposeful kick from 20 meters. It slowly climbed skyward on a wire as it hurtled just below the crossbar above a defender's head before he could blink. Hidegkuti — indelibly writing his signature as author of England's maiden defeat — appeared earnestly once again by one-timing a volley into goal off a arc before the ball came in contact with the ground, accomplished his famous hat-trick and crushed the paleo-tactics in worldwide application since 1925 at the whistle 6–3.

Of the many in attendance who would figure prominently in English football's future, one initially had taught mainland Europeans and the Hungarians a great deal about football. He was the oft-slighted and under appreciated coach genius, 71-year old Jimmy Hogan. Hogan was an outsider in English circles who arrived with the youth team of Aston Villa to watch his colleague and friend Gusztáv Sebes play a game that represented a new archetype that came to dominate their thoughts. Hogan had been a pioneering journeyman coach, even a football missionary before the First World War who imparted an elegant, almost esoteric knowledge of the game on the Continent and successfully coached Hungary's MTK into a league leader in the 1920s. Hogan's beliefs formed a minority view along with other radical managers like Sebes and Hugo Meisl of Austria. They championed a brand of free flowing soccer where possession and therefore skillful passing sequences were keys to the game united to varying flexibility. The Hungarians dedicated their great triumph to the old man who had given them much. At game's end, Hogan commented that a new order in football had been shaped dictated by the visiting team - "...that was the football I've always dreamed of.."

The Magical Magyars' performance was revelatory that seemed to presage a tactical revision of the game from static models to be the flexibility basis for much if not all that followed in the game. It focused a compelling case of modernist football up against the dated pre-war operating system, as it peered toward a versatile new age that allowed players maximum freedom of movement. It also more than ordinary as a major vindication of Continental football's progress. The match's value for the Magical Magyars' was inestimable as their magnum opus. For football itself, the panoramic prevision of how the future game would be played stimulated new ideas both within and outside the Continent, and minds started to change about the fluidity of the game, finding final value with the world champion Brazilian sides of 1958, 1962, 1970. The famous Wembley game of 1953 reverberated around the globe as a historical strategic and tactical watershed that made front-cover news in many countries, subject to acres of newsprint, books, informative scholarship and introspective self-analysis that has taken on a near mythical station in football lore — arguably being the 20th century's most influential match.

England 1 : Hungary 7 (1954)

No other home game before or since has attracted so much enthusiasm in Hungary as the special return fixture with England that served as a build-up to the 1954 World Cup in three weeks' time. Unbowed England came to Budapest anxious to restore the old ways in football's hierarchy and lift the chagrin of the Wembley match being caught unaware to the developments happening in Europe. Inside Hungary, expectations were reaching a feverish pitch. Taking place would be an emphatic elevation of European football kings under view of a large press corps and spellbound home nation in Hungary's stately new Nation's Stadium — built in order to ensure the continuity of the Eastern Bloc's bellwether squad in sport.

Over a million Hungarians (one in 9 out of the population) petitioned for tickets, and many gaining entry used carrier pigeons to send their tickets to friends and family awaiting at home. The whole nation seems completely absorbed in the prospective game listening on radio. English coach Walter Winterbottom debuted a re-formed squad to stand fast against the Hungarians by putting in seven new starters, keeping only Gil Merrick, Jackie Sewell, and Billy Wright from the original Wembley team.

To a huge 105,000 crowd on a bright and hot summer day in Budapest, Hungary's star-spangled offense threw a searchlight on the home side's stirring possibilities for the 1954 World Cup. It was against this backdrop of national ecstasy that the Golden Team hit their most sustained and brilliant form crescendoing with great power in their best ever home performance. Early on the Hungarians found their muse. They discovered England hadn't mended the tactical flaws witnessed in the first game, insisting on long standing tough perennial conservatism to press home their game. Eight minutes into the game, left-back Mihály Lantos's keen 22-yard free kick along the ground began a outpouring that saw three long racetrack counter-attacks exporting goals past keeper Gil Merrick. Three sharply driven goals from mid-range with Puskás and Kocsis netting two apiece and Hidegkuti one set in motion a collapse of English soccer of historic import.

Syd Owen played at center-half for England and remembered the occasion well. When later asked what it felt like playing the Hungarians his reply was: "...it was like playing people from outer space."

With a new puristic rigor that seemed to reach a sublime level, the game was deeply satifying for the Magical Magyars as their ascent went from relative to absolute. The high-scoring 7-1 scoreline still reflects the worst defeat by margin for England in the world game. World champion in all but in name, all Europe saw the Hungarians heading for a rendezvous with the soccer sorcerers from South America, Brazil or world champion Uruguay for the world title.

The 1954 World Cup

To the majority of vantage points, both inside and outside the game, only one goal remained for Hungary as it was preceeding without fault in the high summer of 1954 towards the holy grail of football. Football world supremacy would be decided after the contrasts between Hungary and that of football superpowers from Latin America were seen. The Magical Magyars were appraised by general consent as having the most tactically astute, redoubtable team to carry through these of aims with plenty of talent to match.

The 16 finalists were grouped in fours and only two would see the next round in the quarter-finals. Hungary shared Group B with Turkey, West Germany and South Korea.

On June 17, 1954 in Zurich, the Magyars opened their campaign against a debutant South Korean team, who were making their first journey to the World Cup finals. In spite of the Korean War's ending the year before, flights commercially out from Korea didn't exist, and the Korean players had to endure a tiring six-day odyssey by air, sea, road and rail to arrive to the tournament in Switzerland that added to their unrest. On less than a full day's recovery, the Koreans were to walk onto the field against senior commitment and unavoidable head wind. The pentameter of the Hungarians' virtuosity regaled spectators with a performance that was record breaking as the ball moved briskly causing so much movement within twenty minutes half of the Korean team went down with cramps. At the 12th minute Puskás opened the floodgates to a torrential pastiche of goals. Inside forward Sándor Kocsis began his trek towards world fame with 3 goals en route to a 9-0 win to record the largest goal differential ever set in World Cup history.

Three days later, the Hungarians went into action against one of their other group opponents, an unseeded and largely unfashionable West Germany squad of whom not much was expected in the competition. West German manager Sepp Herberger, imbued with a grander project to schedule his team for the best of prospects in the knockout stages, wittingly put out an under-strength squad to rest most of his regulars and gain inputs to what made Hungary so impeccable. Unfolding a plan to reconnoiter and have insight into Hungary's on-field strength, keep his main team fresh and plans unexplored informed his decision to play this enormous gamble. It caused wide criticism back home in West Germany to the contrary. Herberger's contention was that Germany could still qualify for the quarter-finals in spite of a loss.

With fine fettled precision, deft dribbling and colorful passing that would later define Brazilian football's joyous magic for decades, Hungary precipitated themselves against the opposing line and soon glided past bulwarks. To no one's surprise, a heavy programme of soccer assault ensued — the German half was the scene of most activity, their goal heavily leaned upon by a rolling fire and tactical rigor that attacked without interlude. Sándor Kocsis was like a cavalier man possessed, cycling through defensive mazes to dynamically wreck the Mannschaft scheme into inchoate shambles with goals at the 2nd, 21nd, 68nd, 77th minutes.

This match echoes with controversy for the roughness beyond the pale given the Hungarian captain. Being the world's finest player, Puskás was now receiving some very special attention and ungentle marking from all comers he faced. The Hungarian Football Federation would later allege three critical fouls the match's refereeing missed undermined the officiating in part for the rough tactics adopted by the Germans to stop Puskás. Throughout the game, German defender Werner Liebrich was deputed to mark the indefatigable and high spirited Puskás. Spontaneity and braggadocio were not unique events in big games for Puskás. Puskás informed Hungarian-speaking German defender Josef Posipal of his intention to make Liebrich look hopelessly unskillful, slow and ponderous when facing him. Hungary's second goal in the 17th minute is a mesmeric work of Puskás penetrating a station of three German defenders in front of him before sliding a short ball under the diving goalkeeper Toni Turek.

At the height of the game with Hungary in the lead 6-1, Liebrich's challenge was the most devitalizing tackle of concern as Puskás was on the end of a fiece tackle from behind. This put him provisionally out of the tournament with a sorely bruised ankle. The injury was later revealed to be a hairline fracture. The German goal buckled under a full spectra of maneuvers and goals, the game was a 8-3 roasting for the Magyars, but the injury subtraction of Puskás would now throw its competitive future into question.

Hungary's other on-field star Sándor Kocsis was altogether a player of the very first order whose exorbitant scoring talents were completely developed on the ground and in the air. Now the suddenly important Kocsis would gain his own renown in turn to be the leading content provider up front to marshal the side onward.

In West Germany, the public view on Sepp Herberger's decision to run a trial against Hungary and not play at full array was a contentious matter with many demanding his resignation. But regardless, Herberger's approach worked as he had planned. Germany defeated Turkey 7–3 three days later with a mostly rested squad in a requisite playoff to ensure passage into the final group of eight.

"Battle of Berne" (Brazil vs. Hungary 1954)

Background

Football had come relatively early to Brazil, transmitted by the son of a British expatriate, Charles William Miller, who had attended the English public school at Southampton and brought the aristocratic collegian game with him in 1894 to São Paulo. Football was a cliquish pastime of British communities in urban areas of Latin America and after the First World War found a place in the national life of most South American nations across all sections of society. With credentials and a trim that were living at every World Cup, Brazil's emergence was one of a crescendoing work. Their World Cup side of 1938 that managed come in third place showed prospects of vast potential. By the 1950 World Cup, as hosts of the World Cup, Brazil was primed on the cusp of destiny, receiving copious publicity as the highly advertised side ready to win over the world with a strong team of moment. Presented to a still-record audience of 199,850 in the world's largest and most modern Estádio do Maracanã, Brazil met in an unofficial "final" a much weaker Uruguayian team in a game that would haunt Brazilian regards on a national scale. In a game that mattered most, Uruguay initially braced up against Brazil's withering inertia and was down early 0-1. Late in the late, Uruguayan steely determination and arguably history's most famous counter-attack by Juan Schiaffino again put Uruguay 2-1 on the game's pinnacle.

Brazil came with a confidence that was made plain — to lift the chagrin and unhappy change in fortune of the "Maracanazo" that lingered with a team re-organized in a spirit to improve after the 1950 fiasco. South America's top team again was at the door of greatness, dispensing a balanced game that knew the trade on every level. The Seleção's rating of 2010 points reflected their status as the planet's No. 3 team and were archetypal in areas of speed, physicality, soulful passing and dribbling of superb Latin American football. Their backfield was led by defender Djalma Santos, perhaps the greatest right back in the game's annals and his colleague Nilton Santos worked in unison to underpin the strongest attacking fullback tandem in football history. Djalma Santos' virtues of a cool jockeying style was held in high esteem for the high rate of his dispossessions, tackles and stopping the perilous runs and passes of others. Both would have impressively thorough careers together in 70 internationals, gain two World Cup honors and earn enormous credit in barring access to a well-rigged defence around goal. At the heart of Brazil's play stood one of midfield's greatest figures, Didi, a player to whom the ball was often channeled. After winning the 1958 World Cup, he would wear the title "world's greatest player", around him were attached players of real talent.

The 1954 quarter-final between Brazil and Hungary was enthusiastically written about by the press covering the game as the "unofficial final". For fans, organizers, and journalists alike the match's ascent and build-out had finally arrived. Captaincy for the game with Puskás out injured was conferred on József Bozsik, the day's most gifted midfielder and the game's elite winger Zoltán Czibor spelled Puskás at inside-left.

The Match

On June 27, 1954, even without their captain Puskás, the Magical Magyars summoned capital effort and skill early. After three minutes, Nándor Hidegkuti took receipt of the ball from the left side of the penalty box. In a scramble for it, half the Brazilian team funneled to the area with the quickest of speed where pandemonium reigned before Hidegkuti mightily plowed into the ball with tremendous backlift through a wall of defenders to evoke high emotion in the 60,000 who had gathered. Mere minutes later, Hidegkuti momentarily dwelt on the ball before lofting an arch from midfield, then Kocsis out-leapt tight two-man marking to steer a long diagonal header into the net, 2–0 Hungary after 7 minutes. The proud Seleção was ill at ease by the jarring pace of the immediate scores visited upon them. Afterward, both teams strove in an attrition battle royal to stem the other's advance and curb developing plays through a policy that courted injury, unrelenting combative hard fouling that saw players clashing fiercely in contention for the ball amid palpable tension. The game became erratic with continual interruptions after each free kick was awarded; an unheard sum of 42 free kicks saw many piercing challenges lacking respect, some were violently brutal that reminds one of the wanton intensity on that fateful day. Of these, tripping that felled forward Indio in the penalty area was converted from the penalty spot by Djalma Santos, 2–1.

By the 60th minute, the match was 3-1 and seemingly out of reach for Brazil, who left nothing undone to keep within the match. Shortly afterwards, Julinho slalomed in to stroke a curling drive, the ball knuckling into the top right corner of the net from the opposing side of the penalty box in one finest speculative efforts seen at the tournament, 3–2. József Bozsik, a deputy member in the Hungarian Parliament took umbrage and feeling that he was tackled unfairly retaliated by punching Nilton Santos and soon both were in fisticuffs and expelled. Brazil energetically surged forward with their remaining stores, but Didi hit the crossbar in what would be their last chance to draw level. But there was trouble elsewhere on the pitch. Djalma Santos put aside all ideas of playing football to pursue Czibor about the field livid in a fit of rage. Nothing daunted in the dying minutes of the game, Czibor was seen streaking down the field's periphery and shuttled a well-flighted ball to the center goal area to a lone Sándor Kocsis, the latter with his head fiercely smashed in the final score 4–2.

The last moments of the game was little more than a running sparing match between the two great teams. Brazil forward Humberto Tozzi kicked Hungary's Gyula Lorant prior to the whistle and was genuflect on bended knees not to be sent off by referee, Arthur Ellis, who mandated the game's third red card.

As the game concluded, the excesses and tensions on the field continued unabated off of it ending in emotional turmoil. Sudden rumors circulated that a spectating Puskás allegedly struck Pinheiro with a bottle causing a three-inch cut, while most reports hold a spectator culprit not the Hungarian captain. Hamstrung throughout the game by the Mighty Magyars and with dreams deferred until the arrival of the precocious footballing-talent in Pelé four years later, an incensed Brazil gave vent by having their fans, photographers, trainers, reserve players and coaches invade the pitch with the Swiss police powerless to impose rule on the tumult and disorder that followed. In the tunnel of the stadium, Brazilian players smashed the light bulbs leading to the Hungarians' dressing room and ambushed the Magyars in their quarters where a melee in virtual darkness occurred, there broken bottles, fists and shoes were used as weapons. At least one Hungarian player was rendered unconscious and manager Gusztáv Sebes ended up requiring four stitches after being struck by a broken bottle.

Many year later, the game's English referee Arthur Ellis commented: "I thought it was going to be the greatest game I ever saw. But it turned out to be a disgrace."

"Never in my life have I seen such cruel tackling."- observed The Times correspondent.

The infamous occasion of the "Battle of Berne" is still talked about today among the old timers in Hungary, with many expressing the opinion that this was the first "final" of the three that Hungary had to play at the 1954 World Cup. It has also been put forward that the Magyars' achievement staved off and prevented Brazil from beginning their procession of World Cup titles in 1954, added to those of 1958, 1962, and 1970.

"The Greatest Game Ever Played" (Uruguay vs. Hungary 1954)

The collision of world champion Uruguay with the Mighty Hungarians in the 1954 Semi-Final is described by Cris Freddi's History of the World Cup as:

"...an outstanding candidate for the greatest international match of all time."

Background

In the early part of the 20th century, up to and including 1954, Uruguay dominated international football in South America. A nation of a mere three million was disproportionately per capita the most successful football nation in the world. Running in parallel with how football developed in Latin America, a sport institutionalized in society and its cultural life after pockets of British expatriates had exported the collegiate game all throughout the Anglosphere and beyond, Uruguay rapidly made itself known on the world stage before its larger neighbors could catch them, and was prominent in establishing South America as a coequal centre of the game.

- Still to be Written

"The Miracle of Berne" (1954 World Cup Final, West Germany vs. Hungary)

Background

The media establishment wrote about an incontestable team forged in the heat of innumerable sessions of practice about to meet a collection of pseudo-amateurs from West Germany that did not have a yet true national league of their own. Hungary had secured their second consecutive World Cup Final (their 1938 team had lost to Italy 4-2 in Paris). Hungary, on the page, was in a unassailable position with the highest rated squad in history with a display of skillful technique in attack that overthrew everyone on its way to scoring 6.25 goals/game in the tournament.

The Magyars had advanced to an astonishing record of 34 wins, 6 draws, and 1 defeat since August 1949, and were registers of a consecutive unbeaten run in their last 31 matches. They had not seen defeat for 49 months. Opposing groups vying in these matches paled in comparison. Most were overrun by percussive fast-moving tensions of genius that treated the ball beautifully to find equations with selectively tailored passes interspersed with salvos as they succumbed to a crushing rataplan of 4.46 goals-per-game. The old firm around Gyula Grosics earnestly had a star quality about it too. Before Gordon Banks and Lev Yashin there was Grosics. He was Europe's most noted and gifted goalkeeper since the Spanish Ricardo Zamora and a fine athlete in the goalkeeping arts. The formation of defense around him did their best to horizontally engage and deflect onsetting plays made against them (allowing 1.15 goals/game). The team seemed to catalyze some sort of footballing perfection.

The Hungarians' 41 match narrative had staged coups that had far and wide implications where a brilliant new essential reality of the game was first revealed. They rendered theory into real form with a quantum leap reformation of the game that seemed to channel the spirit of the modern age with extraordinary richness. First sorting out its intricacies, then they played everyone worth playing and carried all before them by the alliance of skill to imagination with a plentitude of power to overwhelm. Within a span of two years, the Olympic and European champions had crushed teams with four World Cup titles between them (prior to 1954 there were only four World Cups). The Hungarians had de-mystified the patriarchal sway the masters of the game, England, had on the world's imagination with two absorbing matches 6-3 abroad and 7-1 at home that brought universal renown hailed by all. The adventures of both South American finalists of the 1950 World Cup Final, mighty Brazil and the reigning world champion Uruguay met a dead end, solidly beaten and eclipsed 4-2 by a stronger wording of power.

The Hungarians' 8-3 victory over West Germany at group stage was seen as a dress rehearsal to a level of expertise Hungary would bring against a West German side that was starting to really surprise many. The championship match, apparently, were to be a mere fixture in formality Hungary were to visit to assume their rightful place as the greatest football side that ever was. Main thoughts were that West Germany were to face the planet's best team framed to their finest hour: the cavalier outpouring of Kocsis, who had scored 13 goals in the last 5 games and who entered the Final with 48 goals in 40 appearances allied to the newly chartered playmaker position and wiles of the seasoned campaigner Hidegkuti, and the game's fastest winger Zoltán Czibor who did brisk trade with his positive buccaneering end runs on the periphery. József Bozsik was their playing conscience and metronome from midfield, and under his baton the Hungarians had flourished.

A veritable media blitz and big drama surrounded the world's greatest goalscoring player, namely Puskás, whose fitness was the main focus of attention. He had not played since the first German game where they won 8-3. On everyone's mind and the great sought after question of the tournament now became whether Puskás was hale and able to naturally play free of injury. It was most often queried by the press, and reports vacillated back and forth on whether the great star's ankle had healed properly. Since Puskas' withdrawal, Sándor Kocsis was at the cynosure of all eyes and the constant target of unending two-man coverage of teams who sought to protect themselves, sending willing trackers to hang off the shoulders of the much lionized forward wherever he went. Sebes figured to draw off some of that attention. Perhaps where hugely popular sentiment overruled pragmatism, it was the day before the match where Puskás was given a fitness exam by the medics and cleared to play. Even at "80%" per manager Sebes he was optimally more than a match than virtually anyone. Puskás entered the Final with a astonishing 68 goals to his credit in 57 matches to provide the exclamation. The team received a copious amount of letters and telegrams from well-wishers from everywhere where Hungary supporters lodged.

Sepp "Boss" Herberger was appointed national manager of the German team in 1936 during the high point of Nazi Germany, perhaps himself out of careerism joining the incumbent party in 1933. Later rehabilitated after the war for his political sympathies, found himself back at the top post, there tasked in re-building the West German national side in 1950, a position he would hold until 1964. Always one to dispense pearls of wisdom to his players, with the desired discipline he built his national side around the significant talents of one of his best players, goalscoring midfielder Fritz Walter. Walter had been in detention in 1945 and was on the verge of being transferred to a Soviet gulag with the general German prisoner of war population when a stranger's providential involvement rescued both his life and destiny to captain the West German side. Some years earlier, a Hungarian spectator recalled seeing Walter play for Germany, and the sight was sufficient to remember after these many years. The Hungarian prison guard misdirected the Soviet captors to the notion that Walter's real identity was Austrian and that he was not a Germany national.

Herberger fashioned messages of stamina, strength, diamond-hard determination and preparedness that very much took hold in his players, who would in turn forever sculpt and hew out these exemplar virtues on the soccer field for all German football. German players were beholden to Herberger, their headmaster, ever puritanical, a monumental mason of character and team-building traits his responding players living proof, having now achieved a reputation in Germany akin to that of an eminent war-strategist. The German master patiently watched and gained inputs, studying the great Hungarian team until he felt he understood them. The Hungarians' great 6-3 triumph over England a year earlier had been put to film, the Germans put in homework in pouring over meticulous details anxious to do better than the English. Herberger himself had a original close viewing of Hungarian tactical maneuvers in their own 3-8 defeat at group stage, and came off ever more informed than before.

The party opposite had Gusztáv Sebes, ever the stylist, thinker, innovator, culturally permissive to the end that Puskás practically ran affairs both on an off the field, presiding over a dream squad of the most elevated players and illustrated what it was to play the game properly as a vision of joy and perfection. The duel between the two grandmasters also reached onto the field, finding two sentimental favorites in their captains Fritz Walter and Puskás.

The unseeded Germans after their defeat took a departing path to converge on the Final aroused a team unlike before — transacting supremely driven activity to the intrigue of most pundits and foreign correspondents. The Germans routed the Turks 7-3 in a playoff win, and proceeded to capture big upsets over Yugoslavia (2-0) and Austria (6-1). A hard-working coalition of German questers had won the palm to the Final harnessing an inner source of gripping esprit, vitality and an unfeigned singleness of determined purpose was the outside view. Many of the amateur German players held day jobs, few could properly locate the cause for this Cinderella group's marvelous form that was in peak condition. The strength of every German player seemed to undergo a renaissance.

The eve of the match was anything but restful for the Hungarians. They still needed the right amount of recuperation after two devitalizing matches against the world's two foremost teams had tested the resilience of their great players. Outside their hotel were Swiss brass bands practicing inauspiciously for the Swiss national brass-band competition complete with parades that seem to live on until two o'clock the next morning, denying many players the rest they so needed. Arguments did develop among the players after their pre-game meal as to whether Puskás' role and contribution would be limited and be a liability. Some accused him of selfish motives and wanting to play solely to be the first one to receive the trophy. Hardly anyone in the media or the public seriously considered the likelihood of Germany posing a challenge.

The Hungarians had much explaining to do in gaining entry to Wankdorf Stadium during match day. The stadium was full and charged with an electrified atmosphere under a tight police presence. The Germans' team bus that preceded theirs received passage inside, the Hungarians' bus was obliged to park outside with the players having to wade through heaving crowds to make their destination. That left manager Sebes explaining to Swiss police that they were one of the match's arriving teams, and was met by the heavy end of a policeman's rifle butt for his persuasion.

There occurred inside a memorable championship match still very much discussed in Germany and Hungary. The stirring sporting performance would be legendary, for the players it would be the game of their lives. It is generally thought of as the most influential championship sporting encounter of the 20th century that would have ramifications of macro-historical significance for the transformative political and economic climate the verdict would foster in both countries and in postwar Europe.

The Match

As the United States of America was in the midst of holiday-making during its Independence Day celebrations, on July 4, 1954 the city of Berne a half a world away would play host to the highest rated international football match played in the 20th century. Some 30,000 West Germans had crossed the Swiss border to live vicariously through their team, whereas few Hungarians were permitted to travel abroad. Wankdorf stadium was filled beyond capacity, attendance stood at 65,000, what few Hungarians were present were crowded out by the prodigious German presence.

Prior to the match, clouds had broken sending a downpour that seem to portent and load with meaning the unpromising nature of the day's proceedings, raining mightily all day prior to kickoff. The playing field was thus a sodden and sluggish alluvial quagmire that would radically alter the game's complexion and personality. The weatherworn muddy and drenched pitch would soak up the true pace of the Hungarians' superior technical skills, whose beauty in action and playing mannerisms would diminish by many shades. The Germans had met Austria under similar conditions in their semi-final match and had excelled, doggedly keeping at the laborious process in spite of the elements and had won 6-1. Much lore had grown around Fritz Walter back in Germany for his personal drift to thrive at his best when rainy weather were at issue and this aura would be present again — "Fritz Walter Weather" had returned. There were some initial discussion by organizers to re-schedule the game when it decided to continue as usual.

Up front, it would be the old incomparable tridental firm of Puskás, Hidegkuti, Kocsis down the center forward line. On the slightly receding wings Mihály Tóth on the left and Zoltán Czibor was acquainted with a new station at wide right where he'd never played before to stress left-back Werner Kohlmeyer, who apparently suffered from a lack of pace. The Mannschaft aligned their less gifted company as the English had done before, their WM formation's steering board queued Max Morlock, Helmut Rahn, Hans Schäfer and Ottmar Walter, the five of whom had scored 15 goals in their 5 matches. Briton William Ling did the officiating with his assistants Welsh Benjamin Griffiths and Italian Vincenzo Orlandini meandering the sidelines.

As had been often the case in their matches, it was with varsity effort that the Hungarians initiated affairs early. Barely inside of 6 minutes, the ball was propagated and placed to the feet of Sándor Kocsis, who turned upfield and was inside the center Germany penalty area when he jettisoned a hard shot aimed to the left of keeper Toni Turek. The ball met the hindquarters of a German player and sent caroming wide left to a ideally situated forward player. The bouncing ball there met the menacing craft of Ferenc Puskás' left foot, who with clinical art stamped in the first score from an angled lane behind Turek, 1-0. Puskás raised his arms triumphantly to the adulation of his team's supporters and a jubilant congregation crowded around the great star. Barely two minutes later, the sum of all fears in the judgement game for the Mannschaft and a nation of 60 million listening on radio came into being.

Again it was Sándor Kocsis who appeared to be everywhere on the pitch, this time again in the Germany penalty area doing hard battle for possession and was fast approaching the 6-yard box. It was Werner Kohlmeyer, under duress, who thought it wise to back-pass to keeper Turek to re-compose the match in the face of such a foray. A large momentary lapse of coordination by 35-year old Turek caused the slick ball to be mis-handled as it popped loose just inches from his hands. Viewing the uncollected gift was Zoltán Czibor who sprung it free into the open mesa, wheeled around horizontal to the goal to get a full square measure of the empty net and sent spasms of angst and great joy throughout those in attendance and those many millions listening as the ball rolled into the vacant German net. 2-0 Hungary within the 8th minute. Czibor ran to meet this compatriots his right arm raised in buoyant elation. A facsimile of their first 8-3 encounter was beginning to be sculpted and indelible writing on the wall appeared to be in the making — an eminent Hungary would indeed be world champions.

German players, ever minding the match's significance, kept soldiering on with unbending determination as was the motive impulse and will impressed into them by Herberger that acted as the spur. A technical innovation had reached the Germans before the match and secret equipment would spark added lease into their game to become a sort of leveller of contrasts. Fledgling German sports apparel company Adidas had supplied them with revolutionary footwear, a technological breakthrough in shoe design that had exchangeable, screw-in studs that could interface to any playing surface. The new pioneering shoes thoroughly re-translated the match for the Germans, and offered a revealing look at the manifest advantages of brave traction surety and sprightly team movement that stood up to scrutiny on the field's slippery slope. The Hungarians' confident swiftness and action orientation was not what it used to be. Revertential tones spoken of before for individual and collective speed were now more subdued ones on the moist pitch.

Two minutes later, a German player had taken up position on the left flank just above the Hungarian penalty box and drove a keenly struck diagonal forward grounder deep into center near the penalty spot. The brilliant incisive ball split a seam between two defenders. The last Hungarian defender, József Zakariás slid at the ball and made slight contact attempting to nudge it back to Gyula Grosics, but the surface water had held back and de-accelerated its roll. Just seconds before a sortie by Grosics to secure it, into the scene from right raced Max Morlock, the latter with a sliding foot pushed the ungathered ball just inside the left post as both players collided on the wet ground, 2—1.

In the 18th minute, a corner kick was awarded to the German team from the left quadrant of the field. The high arc of the overhead sailing ball was endeavored to be reached by Grocsis who leaped high with Hans Schäfer who was in his immediate presence. Both men jumped simultaneously. Grosics to punch the ball away to secure confines, the reason for Schäfer's jump was to take initiatives to head the ball. At the height of both men's leap, Schäfer fully wrapped his right arm around Grocsis' torso effectively obstructing his jumping motion with a flagrant interfence foul on the keeper that was in clear view of officials. Grosics was tilted in mid-air by the added weight, his balance off kilter, plummeted straight down on his back while Schäfer landed upright. This offense was not called by any of the officials in the match who were mere meters of its viewing. Mere seconds later, Helmut Rahn stroked the ball into an ill-guarded net. Schäfer's liberty and the officials quiet acquiescence had given a dubious unmerited goal to the German cause. The Hungarians were not to be on the receiving end of impartial officiating, and this was becoming apparent, 2-2.

In the 24th minute, from midfield a Hungarian player lofted a speculative lob inside the left part of the German box.

- Still to be Written

International Football's Highest Rated Matches

The Mighty Magyars feature in three of the top 10 highest rated matches all-time. A list of the 10 matches between teams with the highest combined Elo ratings (the nation's points before the matches are given) as of July 16, 2010.

| Rank | Combined points |

Nation 1 | Elo 1 | Nation 2 | Elo 2 | Score | Date | Occasion | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4211 | 2100 | 2111 | 0 : 1 | 2010-07-11 | World Cup F | |||

| 2 | 4161 | 1995 | 2166 | 3 : 2 | 1954-07-04 | World Cup F | |||

| 3 | 4157 | 2050 | 2107 | 2 : 1 | 2010-07-02 | World Cup QF | |||

| 4 | 4148 | 2068 | 2080 | 0 : 1 | 1973-06-16 | Friendly | |||

| 5 | 4129 | 2085 | 2044 | 1 : 0 | 2010-07-07 | World Cup SF | |||

| 6 | 4119 | 2050 | 2069 | 1 : 0 | 1982-03-21 | Friendly | |||

| 7 | 4118 | 2108 | 2010 | 4 : 2 | 1954-06-27 | World Cup QF | |||

| 8 | 4116 | 2141 | 1975 | 4 : 2 | 1954-06-30 | World Cup SF | |||

| 9 | 4113 | 2079 | 2034 | 2 : 1 | 1974-07-07 | World Cup F | |||

| 10 | 4108 | 2015 | 2093 | 1 : 1 | 1977-06-12 | Friendly |

Golden Team Results

Curriculum Vitae, Records & Statistics

- World Record: (June 4, 1950 to Feb 19 1956) 42 victories, 7 draws, 1 defeat ("Miracle of Berne") - 91.0% winning percentage ratio.

- Team Record (June 4, 1950 to July 3, 1954) 31 game undefeated narrative.

- World Record: strongest power rating ever attained in the sport's history using the Elo rating system for national teams, 2166 points (set June 30, 1954).

- World Record: most consecutive games scoring at least one goal: 73 games (April 10, 1949 to June 16, 1957).

- World Record: longest time undefeated in 20th and 21st centuries: 4 years 1 month (June 4, 1950 to July 4, 1954).

- World Record: most collaborative goals scored between two starting players (Ferenc Puskás & Sándor Kocsis) on same national side (159 goals).

- 20th Century Record: Hungary manager Gusztáv Sebes holds the highest ratio of victories per game past 30 matches with 82.58% (49 wins, 11, draws, 6 defeats). Brazil legend Vicente Feola (1955–1966) owns the second highest with 81.25 (46 wins, 12 draws, 6 defeats).

- 20th Century Record: Most International Goals: Ferenc Puskás (84 goals).

- World Cup Record: 27 goals scored in a single World Cup finals tournament.

- World Cup Record: 5.4 goals-per-match in a single World Cup finals tournament.

- World Cup Record: +17 goal differential in a single World Cup finals tournament.

- World Cup Record: 2.2 goals-per-match average for individual goal scoring in a single World Cup finals tournament (Sándor Kocsis 11 goals in 5 games).

- World Cup Record: highest margin of victory ever recorded in a World Cup finals tournament match ( Hungary 9, South Korea 0 - July 17, 1954).

- World Cup Precedent: first national team to defeat two-time and reigning World Cup champion Uruguay in a World Cup finals tournament (Hungary 4, Uruguay 2, semi-final — July 30, 1954).

- World Cup Precedent: Sándor Kocsis, first player to score two hat tricks in a World Cup finals tournament (Hungary 8, West Germany 3 - July 20, 1954 & Hungary 9, South Korea 0 - July 17, 1954).

- National Record: Highest margin of victory recorded by Hungarian national team (Hungary 12, Albania 0 - Sept. 23 1950).

- Precedent: first national side from outside the British Isles to defeat England at home since the codification of association football in 1863, a span of 90 years (Hungary 6, England 3, see "Match of the Century" - Nov. 25 1953).

- Hungary's 7-1 defeat of England in Budapest the next year is still England's record defeat.

- Precedent: first national side in the world to eclipse a 1888 Scottish record of being undefeated in 22 consecutive matches (32 games).

Precedent: first non-South American national side to defeat Uruguay (Hungary 4, Uruguay 2, semi-final — July 30, 1954), breaking a 17 game Uruguayan unbeaten run against non-South American competition dating from May 26, 1924.

- Precedent: first national side to defeat the Soviet Union at home (Hungary 1, Soviet Union 0 - Sept. 23 1956).

- Precedent: first national team in history to simultaneously host the No.1 and No. 2 world record holders for most goals scored internationally (Ferenc Puskás 84 goals, Sándor Kocsis 75 goals) from May 11, 1955 to October 14, 1956.

- Team Record vs. Elo Ranked Opponents: (June 4, 1950 - Oct. 14 1956), vs. world Top 10 ranked opponents: 11 wins, 2 draws, 1 loss / vs. world Top 5 opponents: 4 wins, 0 draw, 1 loss.

Honours

| Olympic medal record | ||

|---|---|---|

| Football | ||

| 1952 Helsinki | Men's Football | |

- Olympic Champions

- 1952

- Central European International Cup

- 1948/53

- World Cup

- Finalist 1954

References

- Rogan Taylor, ed. (1998). Puskas on Puskas: The Life and Times of a Footballing Legend. Robson Books. ISBN 1861051565.