Taharqa

| Taharqa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taharqo, Tirhakah, Tirhaqah, Taharka, Manetho's Tarakos | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Granite sphinx of Taharqa from Kawa in Sudan | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pharaoh | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 690–664 BC | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Shebitku | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Tantamani | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Consort | Takahatenamun, Atakhebasken, Naparaye, Tabekenamun[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | Amenirdis II, Ushankhuru, Nesishutefnut | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Father | Piye | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mother | Abar | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 664 BC | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dynasty | 25th dynasty | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Taharqa was a pharaoh of Egypt and the Kingdom of Kush located in Northern Sudan and a member of the Nubian or Twenty-fifth dynasty of Egypt. His reign can be dated from 690 BC to 664 BC.[3] He was the son of Piye, the Nubian king of Napata who had first conquered Egypt; Taharqa was also the younger brother and successor of Shebitku.[4]

Evidence for the dates of his reign are derived from the Serapeum stela Cat. 192 "which records that an Apis bull who was born and installed (4th month of Peret, day 9) in Year 26 of Taharqa died in Year 20 of Psammetichus I (4th month of Shomu, day 20) having lived 21 years. This would give Taharqa a reign of 26 years and a fraction, in 690-664 B.C."[5] Taharqa was the brother of Shebitku, the previous pharaoh of Egypt. Taharqa explicitly states in Kawa Stela V, line 15 that he succeeded Shebitku with this statement: "I received the Crown in Memphis after the Falcon (ie: Shebitku) flew to heaven."[6]

Biblical references

Scholars have identified him with Tirhakah, king of Ethiopia, who waged war against Sennacherib during the reign of King Hezekiah of Judah (2 Kings 19:9; Isaiah 37:9) and drove him from his intention of destroying Jerusalem and deporting its inhabitants—a critical action that, according to Henry T. Aubin, has shaped the Western world.[7]

The events in the Biblical account are believed to have taken place in 701 BC, whereas Taharqa came to the throne some ten years later. A number of explanations have been proposed: one being that the title of king in the Biblical text refers to his future royal title, when at the time of this account he was likely only a military commander.

According to Francis Llewellyn Griffith, an attractive hypothesis is to identify the Pharaoh as Taharqa before his succession, and Sethos as his Memphitic priestly title, "supposing that he was then governor of Lower Egypt and high-priest of Ptah, and that in his office of governor he prepared to move on the defensive against a threatened attack by Sennacherib. While Taharqa was still in the neighbourhood of Pelusium, some unexpected disaster may have befallen the Assyrian host on the borders of Palestine and arrested their march on Egypt." (Stories of the High Priests of Memphis: The Sethon of Herodotus and the Demotic Tales of Khamuas (1900), p. 11.

The Greek historian Herodotus, who wrote his Histories ca. 450 BC, speaks of a divinely-appointed disaster destroying an army of Sennacherib (2:141): “ when Sanacharib, king of the Arabians and Assyrians, marched his vast army into Egypt, the warriors one and all refused to come to his (i.e., the Pharaoh Sethos) aid. On this the monarch, greatly distressed, entered into the inner sanctuary, and, before the image of the god, bewailed the fate which impended over him. As he wept he fell asleep, and dreamed that the god came and stood at his side, bidding him be of good cheer, and go boldly forth to meet the Arabian host, which would do him no hurt, as he himself would send those who should help him. Sethos, then, relying on the dream, collected such of the Egyptians as were willing to follow him, who were none of them warriors, but traders, artisans, and market people; and with these marched to Pelusium, which commands the entrance into Egypt, and there pitched his camp. As the two armies lay here opposite one another, there came in the night, a multitude of field-mice, which devoured all the quivers and bowstrings of the enemy, and ate the thongs by which they managed their shields. Next morning they commenced their fight, and great multitudes fell, as they had no arms with which to defend themselves. There stands to this day in the temple of Vulcan, a stone statue of Sethos, with a mouse in his hand, and an inscription to this effect - 'Look on me, and learn to reverence the gods.'

Assyrian invasion of Egypt

It was during his reign that Egypt's enemy Assyria at last invaded Egypt. Esarhaddon led several campaigns against Taharqa, which he recorded on several monuments. His first attack in 677 BC, aimed to pacify Arab tribes around the Dead Sea, led him as far as the Brook of Egypt. Esarhaddon then proceeded to invade Egypt proper in Taharqa's 17th regnal year, after Esarhaddon had settled a revolt at Ashkelon. Taharqa defeated the Assyrians on that occasion. Three years later in 671 BC the Assyrian king captured and sacked Memphis, where he captured numerous members of the royal family. Taharqa fled to the south, and Esarhaddon reorganized the political structure in the north, establishing Necho I as king at Sais. Upon Esarhaddon's return to Assyria he erected a victory stele, showing Taharqa's young son Ushankhuru in bondage.

Upon the Assyrian king's departure, however, Taharqa intrigued in the affairs of Lower Egypt, and fanned numerous revolts. Esarhaddon died enroute to Egypt, and it was left to his son and heir Ashurbanipal to once again invade Egypt. Ashurbanipal defeated Taharqa, who afterwards fled first to Thebes, Taharqa died in Thebes [8] there in 664 BC and was succeeded by his appointed successor Tantamani, a son of Shabaka. Taharqa was buried at Nuri - North Sudan .[9]

Depictions

Taharqa was described by the ancient Greek historian Strabo as being counted among the greatest military tacticians of the ancient world.[10]

The Sudanese people consider Piye and Taharqa as historical figures and regarded more than the other pharaohs from the Twenty-fifth dynasty of Egypt.

Will Smith is developing a film entitled The Last Pharaoh, which he will produce and star as Taharqa. Carl Franklin contributed to the script.[11] Randall Wallace was hired to rewrite in September 2008.[12]

Image gallery

-

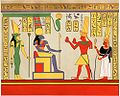

Taharqa offering to Falcon-god Hemen

-

Taharqa as a sphinx

-

Taharqa close-up

-

Taharqa with Queen Takahatamun at Gebel Barkal.

-

Shabti of King Taharqa

-

Chapel of Taharqa and Shepenwepet

-

Taharqa before the god Amun in Gebel Barkal (Sudan), in temple B300

-

Taharqa followed by his mother Queen Abar. Gebel Barkal - room C.

See also

- Victory stele of Esarhaddon

- Statues of Amun in the form of a ram protecting King Taharqa

- Sphinx of Taharqo

References

- ^ Clayton, Peter A. Chronicle of the Pharaohs: The Reign-by-Reign Record of the Rulers and Dynasties of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. p.190. 2006. ISBN 0-500-28628-0

- ^ Dodson, Aidan; Hilton, Dyan (2004). The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05128-3., pp.234-6

- ^ K.A. Kitchen, The Third Intermediate Period in Egypt (1100–650 BC), 3rd edition, 1996, Aris & Phillips Ltd,pp.380-391

- ^ Toby Wilkinson, The Thames and Hudson Dictionary of Ancient Egypt, Thames & Hudson, 2005. p.237

- ^ Kitchen, p.161

- ^ Kitchen, p.167

- ^ Henry T. Aubin, The Rescue of Jerusalem, 2nd edition, 2003, Anchor Canada.

- ^ Historical Prism inscription of ashurbanipal I by Arthur Carl Piepkorn page 36 [1]

- ^ Why did Taharqa build his tomb at Nuri? Conference of Nubian Studies

- ^ Snowden, Before Color Prejudice: The Ancient View of Blacks. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1983, pp.52

- ^ "Will Smith set to conquer Egypt?". Jam Showbiz. 2008-03-23. Retrieved 2008-03-23.

- ^ Michael Fleming (2008-09-08). "Will Smith puts on 'Pharaoh' hat". Variety. Retrieved 2008-09-08.