Rock Hudson

Rock Hudson | |

|---|---|

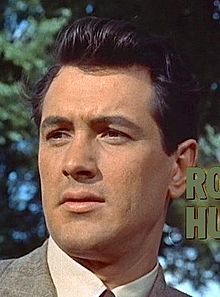

An image from the trailer for Giant (1956) | |

| Born | Roy Harold Scherer, Jr. November 17, 1925 Winnetka, Illinois, U.S. |

| Died | October 2, 1985 (aged 59)[1] |

| Occupation | Actor |

| Years active | 1948–1985 |

| Spouse | Phyllis Gates (1955–1958) |

Roy Harold Scherer, Jr. (November 17, 1925 – October 2, 1985), known professionally as Rock Hudson, was an American film and television actor, recognized as a romantic leading man during the 1950s and 1960s, most notably in several romantic comedies with Doris Day. Hudson was voted "Star of the Year", "Favorite Leading Man", and similar titles by numerous movie magazines. The 6 ft 5 in (1.96 m) tall actor was one of the most popular and well-known movie stars of the time. He completed nearly 70 motion pictures and starred in several television productions during a career that spanned over four decades. Hudson was also one of the first major Hollywood celebrities to die from an AIDS-related illness.[2]

Life and career

Early life

Hudson was born Roy Harold Scherer, Jr., in Winnetka, Illinois, the only child of Katherine Wood (of English and Irish descent), a telephone operator, and Roy Harold Scherer, Sr., (of German and Swiss descent) an auto mechanic who abandoned the family during the depths of the Great Depression. His mother remarried and his stepfather Wallace "Wally" Fitzgerald adopted him, changing his last name to Fitzgerald. Hudson's years at New Trier High School were unremarkable. He sang in the school's glee club and was remembered as a shy boy who delivered newspapers, ran errands and worked as a golf caddy.

After graduating from high school, he served in the Philippines as an aircraft mechanic for the United States Navy during World War II.[3] In 1946, Hudson moved to the Los Angeles area to pursue an acting career and applied to the University of Southern California's dramatics program, but he was rejected owing to poor grades. Hudson worked for a time as a truck driver, longing to be an actor but with no success in breaking into the movies. A fortunate meeting with Hollywood talent scout Henry Willson in 1948 got Hudson his start in the business.

Early career

Hudson made his debut with a small part in the 1948 Warner Bros.' Fighter Squadron. Hudson needed no fewer than 38 takes before successfully delivering his only line in the film.[4]

Hudson was further coached in acting, singing, dancing, fencing, and horseback riding, and he began to feature in film magazines where he was promoted, possibly on the basis of his good looks. Success and recognition came in 1954 with Magnificent Obsession in which Hudson plays a bad boy who is redeemed opposite the popular star Jane Wyman.[5] The film received rave reviews, with Modern Screen Magazine citing Hudson as the most popular actor of the year. Hudson's popularity soared with George Stevens' Giant, based on Edna Ferber's novel and co-starring Elizabeth Taylor and James Dean. Hudson and Dean both were nominated for Oscars in the Best Actor category.

Following Richard Brooks' notable Something of Value (1957) was a moving performance in Charles Vidor's box office failure A Farewell to Arms, based on Ernest Hemingway's novel. In order to make A Farewell to Arms, he had reportedly turned down Marlon Brando's role in Sayonara, William Holden's role in The Bridge on the River Kwai, and Charlton Heston's role in Ben-Hur. Those films went on to become hugely successful and critically acclaimed, while A Farewell to Arms proved to be one of the biggest flops in cinema history.

Hudson sailed through the 1960s on a wave of romantic comedies. He portrayed humorous characters in Pillow Talk, the first of several profitable co-starring performances with Doris Day. This was followed by Lover Come Back, Come September, Send Me No Flowers, Man's Favorite Sport?, The Spiral Road, and Strange Bedfellows, and along with Cary Grant was regarded as one of the best-dressed male stars in Hollywood, and received "Top 10 Stars of the Year" a record eight times from 1957 to 1964. He worked outside his usual range on the science-fiction thriller Seconds (1966). The film flopped but it later gained cult status, and Hudson's performance is often regarded as one of his best.[6][7] He also tried his hand in the action genre with Tobruk (1967), the lead in 1968's spy thriller Ice Station Zebra, a role which he had actively sought and remained his personal favorite, and westerns with The Undefeated (1969) opposite John Wayne.

Later career

Hudson's popularity on the big screen diminished after the 1960s. He starred in a number of made-for-TV movies. His most successful series was McMillan & Wife opposite Susan Saint James from 1971 to 1977. In it, Hudson played police commissioner Stewart "Mac" McMillan with Saint James as his wife Sally. Their on-screen chemistry helped make the show a hit.

In the early 1980s, following years of heavy drinking and smoking, Hudson began having health problems which resulted in a heart attack in November 1981. Emergency quintuple heart bypass surgery sidelined Hudson and his new TV show The Devlin Connection for a year; the show was canceled in December 1982 not long after it first aired. Hudson recovered from the heart surgery but continued to smoke. He was in ill health while filming The Ambassador in Israel during the winter of 1983-84 with Robert Mitchum. The two stars reportedly did not like each other, Mitchum himself having a serious drinking problem.[8] During 1984, Hudson's health grew worse, prompting different rumors that he was suffering from liver cancer, among other ailments, due to his increasingly gaunt face and build.

From December 1984 to April 1985, Hudson landed a recurring role on the ABC prime time soap opera Dynasty as Daniel Reece, the love interest for Krystle Carrington (played by Linda Evans) and biological father of the character Sammy Jo Carrington (Heather Locklear). While he had long been known to have difficulty memorizing lines which resulted in his use of cue cards, on Dynasty it was Hudson's speech itself that began to deteriorate. Hudson was originally slated to appear for the duration of the show's 5th season, however, due to his progressing illness, his character was abruptly written out of the show and died offscreen.

Personal life

Hudson never publicly revealed any specifics regarding his sexuality. While Hudson's career was blooming as he epitomized wholesome manliness, he and his agent Henry Willson kept his personal life out of the headlines. In 1955, Confidential magazine threatened to publish an exposé about Hudson's secret homosexual life; Willson covered this by disclosing information about two of his other clients, in the form of Rory Calhoun's years in prison and the arrest of Tab Hunter at a gay party in 1950. According to some colleagues, Hudson's homosexuality was well known in Hollywood throughout his career.[9] Carol Burnett, who often worked on television and in live theatre with Hudson, was a staunch defender of her friend, telling an interviewer that she knew about his sexuality and did not care. However, after Hudson's death, Doris Day, widely thought to be a close off-screen friend, said she never knew of Hudson engaging in any homosexual behaviour.

Soon after his near-outing in 1955, Hudson married Willson's secretary Phyllis Gates. In Gates' 1987 autobiography My Husband, Rock Hudson, the book she wrote with veteran Hollywood chronicler Bob Thomas, Gates states that she dated Hudson for several months and lived with him for two months before his surprise marriage proposal. She claims to have married Hudson out of love and not, as it was later purported, to stave off a major exposure of Hudson's sexual orientation. The news of the wedding was made known by all the major gossip magazines. One story, headlined "When Day Is Done, Heaven Is Waiting," quoted Hudson as saying, "When I count my blessings, my marriage tops the list." The union lasted three years; Gates filed for divorce in April 1958, charging mental cruelty. Hudson did not contest the divorce, and Gates received an alimony of US$250 a week for 10 years.[10] After her death from lung cancer in January 2006, some informants reportedly stated that she was actually a lesbian who married Hudson for his money, knowing from the beginning of their relationship that he was gay.[11] She never remarried.

According to the 1986 biography, Rock Hudson: His Story, by Hudson and Sara Davidson, Rock was good friends with American novelist Armistead Maupin and a few of Hudson's lovers were: Jack Coates (born 1944); Hollywood publicist Tom Clark (1933–1995), who also later published a memoir about Hudson, Rock Hudson: Friend of Mine; and Marc Christian, who later won a suit against the Hudson estate. In Maupin's Further Tales of the City, Michael Tolliver links up with a closeted macho icon referred to as Blank Blank, which has been interpreted as a thinly disguised caricature of Hudson.

The book, The Thin Thirty, by Shannon Ragland, chronicles Hudson's involvement in a 1962 sex scandal at the University of Kentucky involving the football team. Ragland writes that Jim Barnett, a wrestling promoter, engaged in prostitution with members of the team, and that Hudson was one of Barnett's customers.[12]

A popular urban legend states that Hudson married Jim Nabors in the 1970s. The two, however, never had anything beyond a friendship; the legend originated with a group of "middle-aged homosexuals who live in Huntington Beach", as Hudson put it, who would send out joke invitations for their annual get-together. One year, the group invited its members to witness "the marriage of Rock Hudson and Jim Nabors"; the punchline of the joke was that Hudson would take the name of Nabors's most famous character, Gomer Pyle, and would henceforth be named "Rock Pyle". Despite the obvious impossibility of such an event, the joke was lost on many, and the Hudson-Nabors marriage was, in a few circles, taken seriously. As a result of the false rumor, Nabors and Hudson never spoke to each other again.[13]

AIDS and death

In July 1985, Hudson joined his old friend Doris Day for the launch of her new TV cable show, Doris Day's Best Friends. His gaunt appearance, and his nearly incoherent speech, were so shocking it was broadcast again all over the national news shows that night and for weeks to come. Day herself stared at him throughout their appearance.

Hudson had been diagnosed with HIV on June 5, 1984, but when the signs of illness became apparent, his publicity staff and doctors told the public he had inoperable liver cancer. It was not until July 25, 1985, while in Paris for treatment, that Hudson issued a press release announcing that he was dying of AIDS. In a later press release, Hudson speculated he might have contracted HIV through transfused blood from an infected donor during the multiple blood transfusions he received as part of his heart bypass procedure in 1981. Hudson flew back to Los Angeles on July 31, where he was so physically weak he was taken off by stretcher from an Air France Boeing 747, which he chartered and upon which he was the sole passenger, along with his medical attendants.[14] He was flown by helicopter to Cedars Sinai Hospital, where he spent nearly a month undergoing further treatment. When the doctors told him there was no hope of saving his life, since the disease had progressed into the advanced stages, Hudson returned to his house, 'The Castle', in Beverly Hills, where he remained in seclusion until his death on October 2, 1985 at 08:37 PDT. Hudson was a month and a half away from his 60th birthday.

The disclosure of Hudson's HIV status provoked widespread public discussion of Hudson's homosexuality. In its August 15, 1985 issue, People published a story that discussed Hudson's disease in the context of his sexuality. The largely sympathetic article featured comments from famous show business colleagues of Hudson such as Angie Dickinson, Robert Stack, and Mamie Van Doren, who acknowledged his homosexuality while expressing their support for Hudson.[15] At the time, People had a circulation of in excess of 2.8 million readers;[16] thus, Hudson's homosexuality became fully public as a result of this and other stories.

Among activists who were seeking to de-stigmatize AIDS and its victims, Hudson's revelation of his own infection with the disease was viewed as an event that could transform the public's perception of AIDS. Shortly after Hudson's press release disclosing his infection, William M. Hoffman, the author of As Is, a play about AIDS that appeared on Broadway in 1985, stated: "If Rock Hudson can have it, nice people can have it. It's just a disease, not a moral affliction."[17] At the same time, Joan Rivers was quoted as saying: "Two years ago, when I hosted a benefit for AIDS, I couldn't get one major star to turn out. ... Rock's admission is a horrendous way to bring AIDS to the attention of the American public, but by doing so, Rock, in his life, has helped millions in the process. What Rock has done takes true courage."[18] As Morgan Fairchild said, "Rock Hudson's death gave AIDS a face".[19] In a telegram Hudson sent to a September 1985 Hollywood AIDS benefit, Commitment to Life, which he was too ill to attend in person, Hudson said: "I am not happy that I am sick. I am not happy that I have AIDS. But if that is helping others, I can at least know that my own misfortune has had some positive worth."[20]

Hudson's revelation had an immediate impact on visibility of AIDS, and on funding of medical research related to the disease. Shortly after his death, People reported: "Since Hudson made his announcement, more than $1.8 million in private contributions (more than double the amount collected in 1984) has been raised to support AIDS research and to care for AIDS victims (5,523 reported in 1985 alone). A few days after Hudson died, at 59, on Oct. 2, 1985, Congress set aside $221 million to develop a cure for AIDS."[21] Organizers of the Hollywood AIDS benefit, Commitment to Life, reported that after Hudson's announcement that he was suffering from the disease, it was necessary to move the event to a larger venue to accommodate the increased attendance.[22]

However, Hudson's revelation did not immediately dispel the stigma of AIDS. Although then-president Ronald Reagan and his wife Nancy Reagan were friends of Hudson, Reagan, who was viewed by some as indifferent to the disease and its sufferers, made no public statement concerning Hudson's condition.[23] At the same time, privately, Reagan called Hudson in his Paris hospital room where he was being treated in July 1985, and Nancy Reagan telephoned French President Francois Mitterrand to insure that Hudson would receive the best possible care.[24] Reagan's first public mention of the disease came in response to questions at a September 15, 1985 press conference, nearly two months after Hudson's announcement. In those remarks, Reagan called medical research on AIDS a "top priority." However, when asked, "If you had younger children, would you send them to a school with a child who had AIDS?," Reagan responded equivocally: "[G]lad I'm not faced with that problem today. ... I can understand both sides of it."[25] Several days later, Reagan sent a telegram to the Commitment to Life AIDS benefit, in which he reiterated his position that his administration would make stopping the spread of AIDS a top priority.[26] Nevertheless, Reagan did not publicly address AIDS at length for another two years. [27]

In addition, there was controversy concerning Hudson's participation in a scene in the television drama Dynasty in which Hudson shared a kiss with actress Linda Evans. When filming the scene, Hudson was aware that he had AIDS, but did not inform Evans. Some felt that Hudson should have disclosed his condition to Evans beforehand.[28] At the time, it was known that the virus was present in low quantities in saliva and tears, but there had been no reported cases of transmission by kissing.[29] Nevertheless, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention had warned against exchanging saliva with members of groups perceived to be at high risk for AIDS.[30] According to comments given in August of 1985 by Ed Asner, then president of the Screen Actors Guild, Hudson's revelation caused incipient "panic" within the film and television industry. Asner said that he was aware of scripts being rewritten to eliminate kissing scenes.[31] Later in the same year, the Guild issued rules requiring that actors be notified in advance of any "open-mouth" kissing scenes, and providing that they could refuse to participate in such scenes without penalty.[32] Linda Evans herself appears not to have been angry at Hudson: she asked to introduce the segment of the 1985 Commitment to Life benefit that was dedicated to Hudson.[33]

Hudson was cremated and his ashes scattered at sea. Following his funeral, Marc Christian sued Hudson's estate on grounds of "intentional infliction of emotional distress".[34] Christian tested negative for HIV but claimed Hudson continued having sex with him until February 1985, more than eight months after Hudson knew he had HIV. Hudson biographer Sara Davidson later stated that, by the time she had met Hudson, Christian was living in the guest house, and Tom Clark, who had allegedly been Hudson's partner for many years before, was living in the house.[35]

Following his death, Elizabeth Taylor, his co-star in the film Giant, purchased a bronze plaque for Hudson on the West Hollywood Memorial Walk.[36]

Hudson was the subject of a play, Rock, by Tim Fountain starring Michael Xavier as Rock and Bette Bourne as his agent Henry Willson. It was staged at London's Oval House Theatre in 2008.

Hudson was also the subject of another play, "For Roy", by Nambi E. Kelley starring Richard Henzel as Roy and Hannah Gomez as Caregiver. It was staged at American Theatre Company in Chicago in 2010.

Filmography

- Fighter Squadron (1948)

- Every Girl Should Be Married (1948)

- Undertow (1949)

- One Way Street (1950)

- I Was a Shoplifter (1950)

- Peggy (1950)

- Winchester '73 (1950)

- The Desert Hawk (1950)

- Shakedown (1950)

- Tomahawk (1951)

- Air Cadet (1951)

- The Fat Man (1951) (radio show)

- The Fat Man (1951) (film)

- Bright Victory (1951)

- Iron Man (1951)

- Bend of the River (1952)

- Here Come the Nelsons (1952)

- Scarlet Angel (1952)

- Has Anybody Seen My Gal? (1952)

- Horizons West (1952)

- The Lawless Breed (1953)

- Seminole (1953)

- Beneath the 12-Mile Reef (1953)

- Back to God's Country (1953)

- Gun Fury (1953)

- The Golden Blade (1953)

- Sea Devils (1953)

- Bengal Brigade (1954)

- Magnificent Obsession (1954)

- Taza, Son of Cochise (1954)

- I Love Lucy (1 episode, guest star) (1955)

- All That Heaven Allows (1955)

- One Desire (1955) .... Clint Saunders

- Captain Lightfoot (1955)

- Written on the Wind (1956)

- Giant (1956)

- Never Say Goodbye (1956)

- A Farewell to Arms (1957)

- Something of Value (1957)

- Battle Hymn (1957)

- Twilight for the Gods (1958)

- The Tarnished Angels (1958)

- Pillow Talk (1959)

- This Earth Is Mine (1959)

- Lover Come Back (1961)

- Come September (1961)

- The Last Sunset (1961)

- The Spiral Road (1962)

- "Marilyn[disambiguation needed]"(1963)

- A Gathering of Eagles (1963)

- Send Me No Flowers (1964)

- Man's Favorite Sport? (1964)

- Blindfold (1965)

- A Very Special Favor (1965)

- Strange Bedfellows (1965)

- Seconds (1966)

- Tobruk (1967)

- Ice Station Zebra (1968)

- The Undefeated (1969)

- Ruba al prossimo tuo (1969)

- Hornets' Nest (1970)

- Darling Lili (1970)

- Once Upon a Dead Man (1971) (TV)

- Pretty Maids All in a Row (1971)

- Showdown (1973)

- Embryo (1976)

- McMillan & Wife (29 episodes, 1971–1977)

- Avalanche (1978)

- Wheels (1978) TV mini-series

- The Martian Chronicles (1979) TV mini-series

- The Mirror Crack'd (1980)

- Superstunt II (1980)

- NBC Family Christmas (1981)

- The Star Maker (1981)

- The Devlin Connection (13 episodes, 1982)

- World War III (1982) TV mini-series

- The Vegas Strip War (1984)

- The Ambassador (1984)

- Dynasty (14 episodes, 1984–1985)

Awards

- Academy Award: Nominated 1956 Best Actor for Giant

- Golden Globe: Winner 1959 World Film Favorite: Male actor

- Golden Globe: Winner 1960 World Film Favorite: Male actor

- Golden Globe: co-Winner with Tony Curtis 1961 World Film Favorite: Male actor

- Golden Globe: Winner 1963 World Film Favorite: Male actor

- Hudson received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 6104 Hollywood Boulevard.

See also

Bibliography

- Clark, Tom (1990). Rock Hudson, Friend of Mine. New York, NY: Pharos Books. ISBN 0886875625.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Gates, Phyllis (1987). My Husband, Rock Hudson. Garden City, NY: Doubleday. ISBN 0385240716.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Hudson, Rock (1986). Rock Hudson: His Story. New York: Morrow. ISBN 0688064728.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Ragland, Shannon P. (2007). The Thin Thirty. Louisville, KY: Set Shot Press. ISBN 097912221X.

References

- ^ Michael Binyon (1985-10-03). "Aids victim Rock Hudson dies in his sleep aged 59". The Times. p. 1.

{{cite news}}: External link in|newspaper= - ^ http://www.tcmdb.com/participant.jsp?participantId=90260%7C133734&afiPersonalNameId=null

- ^ Berger, Joseph, "Rock Hudson, Screen Idol, Dies at 59", The New York Times, Oct. 3, 1985. Retrieved 2011-02-12.

- ^ The Man Who Invented Rock Hudson: The Pretty Boys and Dirty Deals of Henry Willson by Robert Hofler, Carroll & Graf, 2005, pp. 163-164 ISBN 0-7867-1607-X

- ^ Berger, Joseph, "Rock Hudson, Screen Idol, Dies at 59", The New York Times, Oct. 3, 1985. Retrieved 2011-02-12.

- ^ YouTube - Rock Hudson in Seconds

- ^ Apollo Movie Guide's Review of Seconds

- ^ Server, Lee Baby, I Don't Care (2001)

- ^ Yarbrough, Jeff. "Rock Hudson: On Camera and Off, The Tragic News That He Is the Most Famous Victim of An Infamous Disease, AIDS, Unveils the Hidden Life of a Longtime Hollywood Hero", People Magazine, Vol.24, No. 7, August 12, 1985. Retrieved 2011-02-12.

- ^ Dennis Mclellan (January 16, 2006). "Phyllis Gates: Her marriage to Hudson had fan magazines raving". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2007-09-05.

- ^ Robert Hofler (2006). "Outing Mrs. Rock Hudson: the obits after Phyllis Gates died in January omitted some important facts: Those who knew her say she was a lesbian who tried to blackmail her movie star husband". CNET Networks, Inc. Archived from the original on December 19, 2007. Retrieved December 20, 2007.

- ^ Ragland, Shannon P. (2007). The Thin Thirty. Louisville, KY: Set Shot Press. ISBN 097912221X.

- ^ Barbara Mikkelson (August 10, 2007). "Good Nabors Policy". Snopes. Retrieved 2007-09-05.

- ^ Shilts, Randy. And the Band Played On: Politics, People, and the AIDS Epidemic. New York: St. Martin's Press. 1987. p.580. ISBN 0-312-00994-1

- ^ Yarbrough, Jeff. "Rock Hudson: On Camera and Off, The Tragic News That He Is the Most Famous Victim of An Infamous Disease, AIDS, Unveils the Hidden Life of a Longtime Hollywood Hero", People Magazine, Vol.24, No. 7, August 12, 1985. Retrieved 2011-02-12.

- ^ Diamond, Edwin. Celebrating Celebrity: The New Gossips. New York Magazine, Vol. 18, No. 19. May 13, 1985.

- ^ Yarbrough, Jeff. "Rock Hudson: On Camera and Off, The Tragic News That He Is the Most Famous Victim of An Infamous Disease, AIDS, Unveils the Hidden Life of a Longtime Hollywood Hero", People Magazine, Vol.24, No. 7, August 12, 1985. Retrieved 2011-02-12.

- ^ Yarbrough, Jeff. "Rock Hudson: On Camera and Off, The Tragic News That He Is the Most Famous Victim of An Infamous Disease, AIDS, Unveils the Hidden Life of a Longtime Hollywood Hero", People Magazine, Vol.24, No. 7, August 12, 1985. Retrieved 2011-02-12.

- ^ "BBC NEWS - Entertainment - The show goes on in Aids battle". news.bbc.co.uk. November 24, 2003. Retrieved 2008-07-27.

- ^ Berger, Joseph, "Rock Hudson, Screen Idol, Dies at 59", The New York Times, Oct. 3, 1985. Retrieved 2011-02-12.

- ^ "Rock Hudson: His Name Stood for Hollywood's Golden Age of Wholesome Heroics and Lighthearted Romance—Until He Became the Most Famous Person to Die of Aids", People Magazine, Vol. 24 No. 26, Dec. 23, 1985. Retrieved 2011-02-11

- ^ Harmetz, Aljean. "Hollywood Turns Out for AIDS Benefit", The New York Times, Sept. 20, 1985. Retrieved 2011-02-11

- ^ Boffey, Philip M. "Reagan Defends Financing for AIDS", The New York Times, Sept. 17, 1985. Retrieved 2001-02-11.

- ^ Yarbrough, Jeff. "Rock Hudson: On Camera and Off, The Tragic News That He Is the Most Famous Victim of An Infamous Disease, AIDS, Unveils the Hidden Life of a Longtime Hollywood Hero", People Magazine, Vol.24, No. 7, August 12, 1985. Retrieved 2011-02-12.

- ^ Boffey, Philip M. "Reagan Defends Financing for AIDS", The New York Times, Sept. 17, 1985. Retrieved 2001-02-11.

- ^ Harmetz, Aljean. "Hollywood Turns Out for AIDS Benefit", The New York Times, Sept. 20, 1985. Retrieved 2011-02-11

- ^ Boffey, Philip M. "Reagan Urges Wide AIDS Testing But Does Not Call for Compulsion", The New York Times, June 1, 1987. Retrieved 2011-02-11

- ^ Haller, Scot. “Rock Hudson's Startling Admission That He Has AIDS Prompts An Urgent Call for Action—And Some Extreme Reactions”, People Magazine, Vol. 23, No. 13, Sept. 23, 1985. Retrieved 2011-02-11.; Should Actors Take AIDS Test Before Filming a Kiss?Jet magazine, Vol. 68, No. 26, Sept. 9, 1985.

- ^ Should Actors Take AIDS Test Before Filming a Kiss?Jet magazine, Vol. 68, No. 26, Sept. 9, 1985.

- ^ "Rock Hudson: His Name Stood for Hollywood's Golden Age of Wholesome Heroics and Lighthearted Romance—Until He Became the Most Famous Person to Die of Aids", People Magazine, Vol. 24 No. 26, Dec. 23, 1985. Retrieved 2011-02-11

- ^ Harmetz, Aljean. "Old and New Hollywood Seen in Attitude to AIDS", The New York Times, Aug. 8, 1985. Retrieved 2011-02-11.

- ^ Harmetz, Aljean. "A Rule on Kissing Scenes and AIDS", The New York Times, Oct. 31, 1985. Retrieved 2011-02-11.

- ^ Harmetz, Aljean. "Hollywood Turns Out for AIDS Benefit", The New York Times, Sept. 20, 1985. Retrieved 2011-02-11

- ^ Willard Manus (18 December 2000). "The Cleaning Man Airs Rock Hudson's Dirty Laundry in L.A." Playbill. Retrieved 2007-09-05.

- ^ Marc Christian (March 29, 2001). "Rock Hudson's Ex-Lover Speaks Out" (Interview). Interviewed by Larry King. Retrieved 2007-09-05.

{{cite interview}}: Unknown parameter|callsign=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|program=ignored (help) - ^ http://lisaburks.typepad.com/gravehunting/celebrity_memorials/

External links

- Rock Hudson at Find a Grave

- Rock Hudson at IMDb

- Transcript of CNN Larry King 7. June 2001, Special on Rock Hudson offscreen with Dale Olson

- Transcript of CNN Larry King 1. October 2003, 18th anniversary of Hudson's death

- Rock Hudson biography at TCM

- Actors from Illinois

- AIDS-related deaths in California

- American film actors

- American military personnel of World War II

- American television actors

- American people of German descent

- American people of English descent

- American people of Irish descent

- California Republicans

- LGBT people from the United States

- New Trier High School alumni

- People from Winnetka, Illinois

- People self-identifying as alcoholics

- United States Navy sailors

- 1925 births

- 1985 deaths