Old Testament

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Bible |

|---|

|

|

Outline of Bible-related topics |

The Old Testament or Hebrew Scriptures are the collection of books that forms the first of two parts of the Christian Biblical canon. The contents of the Old Testament canon vary from church to church, with the Orthodox communion having 51 books: the shared books are those of the shortest canon, that of the major Protestant communions, with 39 books. Christians hold different views of the Old Testament or Old Covenant in contrast to the New Covenant.

All Old Testament canons are related to the Jewish Bible Canon (Tanakh), but with variations. The most important of these variations is a change to the order of the books: the Hebrew Bible ends with the Book of Chronicles, which describes Israel restored to the Promised Land and the Temple restored in Jerusalem; in the Hebrew Bible God's purpose is thus fulfilled and the divine history is at an end, according to Dispensationalism and Supersessionism (see Jewish Eschatology for Jewish beliefs on the subject). In the Christian Old Testament the Book of Malachi is placed last, so that a prophecy of the coming of the Messiah leads into the birth of the Christ in the Gospel of Matthew.

The Tanakh is written in Biblical Hebrew and Biblical Aramaic, and is therefore also known as the Hebrew Bible (the text of the Jewish Bible is called the Masoretic, after the medieval Jewish rabbis who compiled it). The Masoretic Text (i.e. the Hebrew text revered by medieval and modern Jews) is only one of several versions of the original scriptures of ancient Judaism, and no manuscripts of that hypothetical original text exist. In the last few centuries before Christ, Hellenistic-Jewish scholars produced a translation of their scriptures in Greek, the common language of the Eastern portion of the Roman Empire since the conquests of Alexander the Great. This translation, known as the Septuagint, forms the basis of the Orthodox and some other Eastern Old Testaments. The Old Testaments of the Western branches of Christianity were originally based on a Latin translation of the Septuagint known as the Vetus Latina, this was replaced by Jerome's Vulgate, which continues to be highly respected in the Catholic Church, but Protestant churches generally follow translations of a scholarly reference known as the Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia. In 1943, Pope Pius XII issued the Divino Afflante Spiritu which allows Catholic translations from texts other than the Vulgate, notably in English the New American Bible.

The Hebrew Bible divides its books into three categories, the Torah ("Instructions"), the Nevi'im ("Prophets") (according to some Christians, essentially historical, despite the title), and the Ketuvim ("Writings)," which according to some Christians might better be described as "wisdom" books (the Song of Songs, Lamentations, Proverbs, etc.). The Christian Old Testament ignore this division and instead emphasise the historical and prophetic nature of the canon─thus the Book of Ruth and the Book of Job, part of the Writings in the Hebrew Bible, are reclassified in the Christian canon as history books, and the overall division into Instructions, Prophets and Writings is lost. The reason for this is the over-arching Messianic intention of Christianity - the Old Testament is seen as preparation for the New Testament, and not as a revelation complete in its own right, see Supersessionism for details.

Although it is not a history book in the modern sense, the Old Testament is the primary source for the History of ancient Israel and Judah. The Bible historians presented a picture of ancient Israel based on information that they viewed as historically true. Of particular interest in this regard are the books of Joshua through Second Chronicles.[1][2]

The oldest material in the Hebrew Bible – and therefore in the Christian Old Testament – may date from the 13th century BCE.[3] This material is found embedded within the books of the current Hebrew Bible/Old Testament, which reached their current form at various points between the 5th century BCE (the first five books, the Torah) and the 2nd century BCE,[4] see Development of the Jewish Bible canon for details.

History

The early Christian Church primarily used the Septuagint, often referred to as the LXX, the oldest Greek version of the Hebrew Bible, as its religious text until at least the mid-4th century (Targums were used by Aramaic speakers). Until that time Greek was a major language of the Roman Empire and a major language of the Church (exceptions include Syrian Orthodoxy and the Church of the East which used the Syriac Peshitta and Ethiopian Orthodoxy which used the Geez, and others, see Early centers of Christianity). In the late 1st century, Rabbinic Judaism (see Council of Jamnia) began expressing a strong distrust of the accuracy of the Septuagint and eventually rejected it. Talmudic tradition considers the LXX to be both divinely inspired and full of errors.[5]

Early church teachers and writers reacted with even stronger devotion, citing the Septuagint's antiquity and its use by the Evangelists and Apostles. Being the Old Testament quoted by the Gospels and the Greek Church Fathers, the LXX had an essentially official status in the early Christian world.[5] Following in the steps of Philo and Hellenistic Judaism, they claimed its inspiration was not inferior to that of the original. They argued that divergences of the Septuagint from the current Hebrew text were due to accidents of transmission, or that they were not actual errors, but Divine adaptations of the original for the sake of the future Church.[6]

When Jerome undertook the revision of the Old Latin translations of the Septuagint in about 400 AD, he checked the Septuagint against the Hebrew text that was then available. He came to believe that the Hebrew text better testified to Christ than the Septuagint.[citation needed] He broke with church tradition and translated most of the Old Testament of his Vulgate from Hebrew rather than Greek. His choice was severely criticized by Augustine, his contemporary, and others who regarded Jerome as a forger. But with the passage of time, acceptance of Jerome's version gradually increased in the West until it displaced the Old Latin translations of the Septuagint.[7]

The Hebrew text differs from the Septuagint in some passages that Christians hold to prophesy Christ, and the Eastern Orthodox Church still prefers the Septuagint text as the basis for translating the Old Testament into other languages. The Orthodox Church of Constantinople, the Church of Greece and the Cypriot Orthodox Church continue to use it in their liturgy today, untranslated. Many modern critical translations of the Old Testament, while using the Hebrew text as their basis, consult the Septuagint as well as other versions in an attempt to reconstruct the meaning of the Hebrew text whenever the latter is unclear, undeniably corrupt, or ambiguous.[7]

Many of the oldest Biblical verses among the Dead Sea Scrolls, particularly those in Aramaic, correspond more closely with the Septuagint than with the Hebrew text (although the majority of these variations are extremely minor, e.g., grammatical changes, spelling differences or missing words, and do not affect the meaning of sentences and paragraphs).[8][9][10] This confirms the scholarly consensus that the Septuagint represents a separate Hebrew text tradition from that which was later standardized as the Hebrew text (called the Masoretic Text).[8]

Of the fuller quotations in the New Testament of the Old, nearly one hundred agree with the modern form of the Septuagint and six agree with the Hebrew text.[citation needed] The principal differences concern presumed Biblical prophecies relating to Christ.[citation needed]

Books of the Old Testament

Template:Books of the Old Testament

The Septuagint

In early Christianity the Septuagint was universally used among Greek speakers, while Aramaic Targums were used in the Syriac Church. To this day the Eastern Orthodox Church uses the Septuagint, in an untranslated form. Some scriptures of ancient origin are found in the Septuagint but are not in the Hebrew. These include Additions to Daniel and Esther. For more information regarding these books, see the articles Biblical apocrypha, Biblical canon, Books of the Bible, and Deuterocanonical books.

Some books that are set apart in the Hebrew text are grouped together. For example the Books of Samuel and the Books of Kings are in the Septuagint one book in four parts called "Of Reigns" ([Βασιλειῶν] Error: {{Lang}}: unrecognized language code: gr (help)). Scholars believe that this is the original arrangement before the book was divided for readability. In the Septuagint, the Books of Chronicles supplement Reigns and are called Paraleipoménon ([Παραλειπομένων] Error: {{Lang}}: unrecognized language code: gr (help)—things left out). The Septuagint organizes the Minor prophets as twelve parts of one Book of Twelve.[11]

All the books of western canons of the Old Testament are found in the Septuagint, although the order does not always coincide with the modern ordering of the books. The Septuagint order for the Old Testament is evident in the earliest Christian Bibles (5th century),[11] namely the Codex Vaticanus, Codex Sinaiticus, Codex Alexandrinus and Peshitta.

The New Testament makes a number of allusions to and may quote the additional books (as Orthodox Christians aver). The books are Tobit, Judith, Wisdom of Solomon, Wisdom of Jesus Seirach, Baruch, Epistle of Jeremy (sometimes considered part of Baruch), additions to Daniel (The Prayer of Azarias, the Song of the Three Children, Sosanna and Bel and the Dragon), additions to Esther, 1 Maccabees, 2 Maccabees, 3 Maccabees, 4 Maccabees, 1 Esdras, Odes, including the Prayer of Manasses, and Psalm 151.

In most ancient copies of the Bible which contain the Septuagint version of the Old Testament, the Book of Daniel is not the original Septuagint version, but instead is a copy of Theodotion's translation from the Hebrew.[12] The Septuagint version of the Book of Daniel was discarded, in favour of Theodotion's version, in the second to 3rd centuries; in Greek-speaking areas, this happened near the end of the 2nd century, and in Latin-speaking areas (at least in North Africa), it occurred in the middle of the 3rd century.[12] History does not record the reason for this, and Jerome basically reports, in the preface to the Vulgate version of Daniel, this thing 'just' happened.[12]

The canonical Ezra-Nehemiah is known in the Septuagint as "Esdras B", and 1 Esdras is "Esdras A". 1 Esdras is a very similar text to the books of Ezra-Nehemiah, and the two are widely thought by scholars to be derived from the same original text. It is highly likely that "Esdras B"─the canonical Ezra-Nehemiah─is Theodotion's version of this material, and "Esdras A" is the version which was previously in the Septuagint on its own.[12]

Latin translations

Jerome's Vulgate Latin translation dates to between 382 and 420 CE. Latin translations predating Jerome are collectively known as Vetus Latina texts.

Origen's Hexapla placed side by side six versions of the Old Testament, including the 2nd century Greek translations of Aquila of Sinope and Symmachus the Ebionite.

Canonical Christian Bibles were formally established by Bishop Cyril of Jerusalem in 350 and confirmed by the Council of Laodicea in 363, and later established by Athanasius of Alexandria in 367. The Council of Laodicea restricted readings in church to only the canonical books of the Old and New Testaments. The books listed were the 22 books of the Hebrew Bible plus the Book of Baruch and the Epistle of Jeremy, together with the New Testament containing 26 books, omitting the Book of Revelation, see Development of the Old Testament canon for details.

The Council of Carthage, called the third by Denzinger,[13] on 28 August 397 issued a canon of the Bible restricted to: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy, Josue, Judges, Ruth, 4 books of Kingdoms, 2 books of Paralipomenon, Job, Psalter of David, 5 books of Solomon, 12 books of Prophets, Isaias, Jeremias, Daniel, Ezechiel, Tobias, Judith, Esther, 2 books of Esdras, 2 books of Machabees, and in the New Testament: 4 books of Gospels, 1 book of Acts of the Apostles, 13 letters of the Apostle Paul, 1 of him to the Hebrews, 2 of Peter, 3 of John, 1 of James, 1 of Judas, and the Apocalypse of John.

Other traditions

The canonical acceptance of these books varies among different Christian traditions, and there are canonical books not derived from the Septuagint. For a discussion see the article on Biblical apocrypha.

The exact canon of the Old Testament differs among the various branches of Christianity. All include the books of the Hebrew Bible, while most traditions also recognise several Deuterocanonical books. The Protestant Old Testament is, for the most part, identical with the Hebrew Bible; the differences are minor, dealing only with the arrangement and number of the books. For example, while the Hebrew Bible considers Kings to be a unified text, and Ezra and Nehemiah as a single book, the Protestant Old Testament divides each of these into two books.

Translations of the Old Testament were discouraged in medieval Christendom. An exception was the translation of the Pentateuch ordered by Alfred the Great around 900, and Wyclif's Bible of 1383. Numerous vernacular translations appeared with the Protestant Reformation.

The differences between the Hebrew Bible and other versions of the Old Testament such as the Samaritan Pentateuch, the Syriac, Greek, Latin and other canons, are greater. Many of these canons include whole books and additional sections of books that the others do not. The translations of various words from the original Hebrew may also give rise to significant differences of interpretation.

Literary and philosophical reception

The Old Testament, and its position in world literature, has engendered a large amount of critical discussion, beginning primarily in the 19th century. In Beyond Good and Evil, Friedrich Nietzsche famously wrote:

"In the Jewish Old Testament, the book of divine justice, there are men, things and speeches of so grand a style that Greek and Indian literature have nothing to set beside it. One stands in reverence and trembling before these remnants of what man once was and has sorrowful thoughts about old Asia and its little jutting-out promontory Europe, which would like to signify as against Asia the 'progress of man'. To be sure: he who is only a measly tame domestic animal and knows only the needs of a domestic animal (like our cultured people of today, the Christians of 'cultured' Christianity included) has no reason to wonder, let alone to sorrow, among these ruins - the taste for the Old Testament is a touchstone in regard to 'great' and 'small'."

— Friedrich Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil[14]

Christian views of the Old Covenant

There are differences of opinion among Christian denominations as to what and how Biblical law (generally understood as the "first five books" of the Old Testament or the Old Covenant) applies today. Most conclude that only parts are applicable, such as the Ten Commandments, some conclude that all are set aside by the New Covenant, while others conclude that all are still applicable to believers in Jesus and the New Covenant.

Dada==Historicity of the Old Testament narratives==

Current debate concerning the historicity of the various Old Testament narratives can be divided into several camps:

- One group has been labeled "biblical minimalists" by its critics. Minimalists (e.g., Philip Davies, Thomas L. Thompson, John Van Seters) see very little reliable history in any of the Old Testament.

- Conservative Old Testament scholars generally accept the historicity of most Old Testament narratives with some reservations, and some Egyptologists (e.g., Kenneth Kitchen) argue that such a belief is warranted by the external evidence.

- Other scholars (e.g., William Dever) are somewhere in between. They see clear signs of evidence for the monarchy and much of Israel's later history, though they doubt the Exodus and conquest of Canaan.

See also

- Abrogation of Old Covenant laws

- Covenant (biblical)

- Expounding of the Law

- Law and Gospel

- List of ancient legal codes

- Lost books of the Old Testament

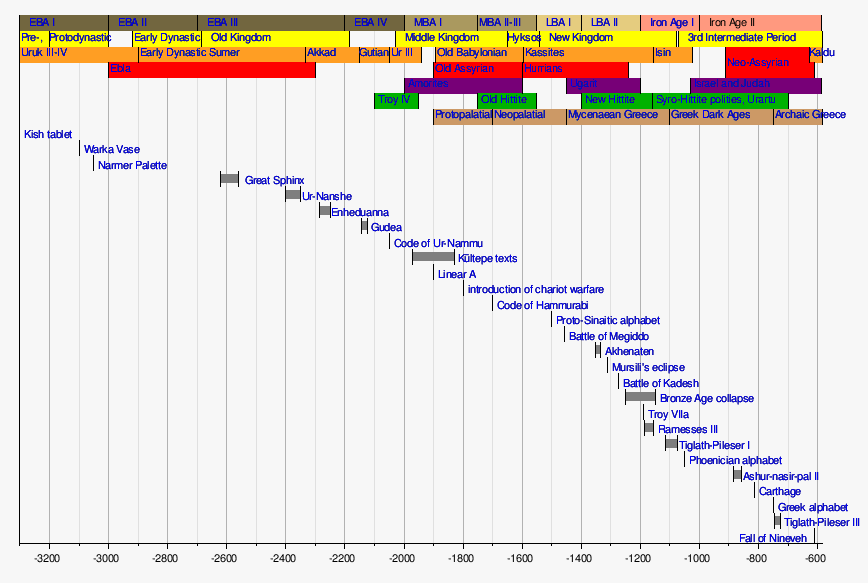

- Old Testament: Timeline

- Quotations from the Old Testament in the New Testament

- List of Hebrew Bible manuscripts

- Table of books of Judeo-Christian Scripture

- Book of Job in Byzantine illuminated manuscripts

References

- ^ Like modern historians, biblical writers sometimes provided "historical" explanations or background information of the events they describe (e.g., 1 Sam. 28:3, 1 Kings 18:3b, 2 Kings 9:14b–15a, 13:5–6, 15:12, 17:7–23).

- ^ Halpern, B. the First Historians: The Hebrew Bible. Harper & Row, 1988, quoted in Smith, Mark S.The early history of God: Yahweh and the other deities in ancient Israel. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.; 2nd ed., 2002. ISBN 978-0802839725, p.14

- ^ "Bible: Growth of Literature." Encyclopedia Americana. Grolier Online . Retrieved March 5, 2010.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica: "Written almost entirely in the Hebrew language between 1200 and 100 BCE"; Columbia Encyclopedia: "In the 10th century BCE the first of a series of editors collected materials from earlier traditional folkloric and historical records (i.e., both oral and written sources) to compose a narrative of the history of the Israelites who now found themselves united under David and Solomon."

- ^ a b "The Septuagint" The Ecole Glossary. 27 December 2009

- ^ H. B. Swete, An Introduction to the Old Testament in Greek, revised by R.R. Ottley, 1914; retrieved 27 December 2009. Reprint, Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson, 1989.

- ^ a b Ernst Würthwein, The Text of the Old Testament, trans. Errol F. Rhodes, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans, 1995.

- ^ a b Karen Jobes and Moises Silva, Invitation to the Septuagint. Paternoster Press, 2001. ISBN 1-84227-061-3. (The current standard for Introductory works on the Septuagint.

- ^ Timothy McLay, The Use of the Septuagint in New Testament Research. ISBN 0-8028-6091-5. The current standard introduction on the NT & Septuagint.

- ^ V.S. Herrell, The History of the Bible, "Qumran: Dead Sea Scrolls."

- ^ a b Jennifer M. Dines, The Septuagint, Michael A. Knibb, Ed., London: T&T Clark, 2004

- ^ a b c d This article incorporates text from the 1903 Encyclopaedia Biblica article "TEXT AND VERSIONS", a publication now in the public domain.

- ^ "Denzinger 186". Catho.org. Retrieved 2010-11-19.

- ^ Beyond Good and Evil, Trans. Hollingdale, Penguin Classics (2003), page 79-80

Further reading

- Anderson, Bernhard. Understanding the Old Testament. (ISBN 0-13-948399-3 )

- Bahnsen, Greg, et al., Five Views on Law and Gospel. (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1993).

- Berkowitz, Ariel and D'vorah. Torah Rediscovered. 4th ed. Shoreshim Publishing, 2004. ISBN 0-9752914-0-8

- Dever, William G. Who Were the Early Israelites? William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., Grand Rapids, MI, 2003. ISBN 0-8028-0975-8

- Gerhard von Rad: Theologie des Alten Testaments. Band 1–2, München, 8. Auflage 1982/1984, ISBN

- Hill, Andrew and John Walton. A Survey of the Old Testament. 2nd ed. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2000. ISBN 0-310-22903-0 .

- Kuntz, John Kenneth. The People of Ancient Israel: an introduction to Old Testament Literature, History, and Thought, Harper and Row, 1974. ISBN 0-06-043822-3

- Lancaster, D. Thomas. Restoration: Returning the Torah of God to the Disciples of Jesus. Littleton: First Fruits of Zion, 2005.

- Rouvière, Jean-Marc. Brèves méditations sur la Création du monde Ed. L'Harmattan, Paris, 2006

- Salibi, Kamal. The Bible Came from Arabia, London, Jonathan Cape, 1985 ISBN 0-224-02830-8

- Silberman, Neil A., et al. The Bible Unearthed. Simon and Schuster, New York, 2003. ISBN 0-684-86913-6 (paperback) and ISBN 0-684-86912-8 (hardback)

- Sprinkle, Joe M. Biblical Law and Its Relevance: A Christian Understanding and Ethical Application for Today of the Mosaic Regulations. Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 2006. ISBN 0-7618-3371-4 (clothbound) and ISBN 0-7618-3372-2 (paperback)

- Papadaki-Oekland, Stella. Byzantine Illuminated Manuscripts of the Book of Job. ISBN 2503532322 & ISBN 9782503532325

External links

- Church Fathers on the Old Testament Canon

- Full text of the Old (and New) Testaments in 42 different languages.

- Full Text of the OT

- Full Text of the OT in a single file (Authorized King James Version, Oxford Standard Text, 1769)

- Old Testament Reading Room Extensive online OT resources (incl. commentaries), Tyndale Seminary

- Old Testament Video Lectures from Yale University

- Scholarly articles on the Old Testament from the Wisconsin Lutheran Seminary Library

- Barry L. Bandstra, "Reading the Old Testament: An Introduction to the Hebrew Bible"

- Old Testament stories and commentary.

- John J. Parsons, "Are Christians restored to the Sinai Covenant?"

- Old Testament Timeline

- Old Testament revised (from Jewish archeolgists Finkelstein / Silberman: some is right, some is a fake, and a lot is missing)