Mass (liturgy)

Mass is the Eucharistic celebration in the Latin liturgical rites of the Catholic Church. The term is used also of similar celebrations in Old Catholic Churches, in the Anglo-Catholic tradition of Anglicanism, in Western Rite Orthodox Churches, and in Lutheran churches. For the celebration of the Eucharist in Eastern Churches, including those in full communion with the Holy See, other terms such as the Divine Liturgy, the Holy Qurbana and the Badarak are normally used. Most Western denominations not in full communion with the Catholic Church also usually prefer terms other than Mass.

For information on the theology of the Eucharist and on the Eucharistic liturgy of other Christian denominations, see "Eucharist" and "Eucharistic theology".

For information on history see Eucharist and Origin of the Eucharist, and with specific regard to the Roman Rite Mass, Pre-Tridentine Mass and Tridentine Mass.

The term "Mass" is derived from the Late Latin word missa (dismissal), a word used in the concluding formula of Mass in Latin: "Ite, missa est" ("Go; it is the dismissal").[1][2] "In antiquity, missa simply meant 'dismissal'. In Christian usage, however, it gradually took on a deeper meaning. The word 'dismissal' has come to imply a 'mission'. These few words succinctly express the missionary nature of the Church" (Pope Benedict XVI, Sacramentum caritatis, 51)

Mass in the Roman Catholic Church

The Council of Trent reaffirmed traditional Christian teaching that the Mass is the same Sacrifice of Calvary offered in an unbloody manner: "The victim is one and the same: the same now offers through the ministry of priests, who then offered himself on the cross; only the manner of offering is different. And since in this divine sacrifice which is celebrated in the Mass, the same Christ who offered himself once in a bloody manner on the altar of the cross is contained and offered in an unbloody manner... this sacrifice is truly propitiatory" (Doctrina de ss. Missae sacrificio, c. 2, quoted in Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1367). The Council declared that Jesus instituted the Mass at his Last Supper: "He offered up to God the Father His own body and blood under the species of bread and wine; and, under the symbols of those same things, He delivered (His own body and blood) to be received by His apostles, whom He then constituted priests of the New Testament; and by those words, Do this in commemoration of me, He commanded them and their successors in the priesthood, to offer (them); even as the Catholic Church has always understood and taught."[3]

The Catholic Church sees the Mass as the most perfect way it has to offer latria (adoration) to God. The Church believes that "The other sacraments, and indeed all ecclesiastical ministries and works of the apostolate, are bound up with the Eucharist and are oriented toward it."[4] It is also Catholic belief that in objective reality, not merely symbolically, the wheaten bread and grape wine are converted into Christ's body and blood, a conversion referred to as transubstantiation, so that the whole Christ, body and blood, soul and divinity, is truly, really, and substantially contained in the sacrament of the Eucharist.[5]

Texts used in the Roman Rite of Mass

The Roman Missal contains the prayers, antiphons and rubrics of the Mass. Earlier editions also contained the Scripture readings, which were then fewer in number. The latest edition of the Roman Missal gives the normal ("ordinary") form of Mass in the Roman Rite.[6] But, in accordance with the conditions laid down in the motu proprio Summorum Pontificum of 7 July 2007, the 1962 edition of the Roman Missal, the latest of the editions that give what is known as the Tridentine Mass, may be used as an extraordinary form of celebrating the Roman Rite Mass.

In the United States and Canada, the English translation of the Roman Missal is at present called the Sacramentary. The Lectionary presents passages from the Bible arranged in the order for reading at each day's Mass. Compared with the scripture readings in the pre-1970 Missal, the modern Lectionary contains a much wider variety of passages, too many to include in the Missal. A Book of the Gospels, also called the Evangeliary,[7] is recommended for the reading from the Gospels, but, where this book is not available, the Lectionary is used in its place.

Structure of the Roman Rite of Mass

Within the fixed structure outlined below, the Scripture readings, the antiphons sung or recited during the entrance procession or communion, and the texts of the three prayers known as the collect, the prayer over the gifts, and the postcommunion prayer vary each day according to the liturgical season, the feast days of titles or events in the life of Christ, the feast days and commemorations of the saints, or for Masses for particular circumstances (e.g., funeral Masses, Masses for the celebration of Confirmation, Masses for peace, to begin the academic year, etc.).

Introductory rites

The priest enters, with a deacon, if there is one, and altar servers. The deacon may carry the Book of the Gospels, which he will place on the altar, and the servers may carry a processional cross and candles and incense. During this procession, ordinarily, the entrance chant is sung.[8] If there is no singing at the entrance, the entrance antiphon is recited either by some or all of the people or by a lector; otherwise it is said by the priest himself.[9] When the priest arrives at his chair, he leads the assembly in making the sign of the cross, saying: "In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit",[10][11][12][13] to which the people answer: "Amen." Then the priest "signifies the presence of the Lord to the community gathered there by means of the Greeting. By this Greeting and the people’s response, the mystery of the Church gathered together is made manifest" (General Instruction of the Roman Missal, 50).[1] The greetings are derived from the Pauline epistles.

Then the priest invites those present to take part in the Act of Penitence, of which the Missal proposes three forms, the first of which is the Confiteor. This is concluded with the priest's prayer of absolution, "which, however, lacks the efficacy of the Sacrament of Penance" (GIRM 51). "On Sundays, especially in the Season of Easter, in place of the customary Act of Penitence, from time to time the blessing and sprinkling of water to recall Baptism may take place" (GIRM 51).

"After the Act of Penitence, the Kyrie is always begun, unless it has already been included as part of the Act of Penitence. Since it is a chant by which the faithful acclaim the Lord and implore his mercy, it is ordinarily done by all, that is, by the people and with the choir or cantor having a part in it" (GIRM 52). The Kyrie may be sung or recited in the vernacular language or in the original Greek.

"The Gloria in Excelsis Deo is a very ancient and venerable hymn in which the Church, gathered together in the Holy Spirit, glorifies and entreats God the Father and the Lamb. ... It is sung or said on Sundays outside the Seasons of Advent and Lent, on solemnities and feasts, and at special celebrations of a more solemn character" (GIRM 53). In accordance with that rule, the Gloria is omitted at funerals. It is also omitted for ordinary feast-days of saints, weekdays, and Votive Masses. It is also optional, in line with the perceived degree of solemnity of the occasion, at Ritual Masses such as those celebrated for Marriage ("Nuptial Mass"), Confirmation or Religious Profession, at Masses on the Anniversary of Marriage or Religious Profession, and at Masses for Various Needs and Occasions.

"Next the priest invites the people to pray. All, together with the priest, observe a brief silence so that they may be conscious of the fact that they are in God’s presence and may formulate their petitions mentally. Then the priest says the prayer which is customarily known as the Collect and through which the character of the celebration is expressed" (GIRM 54).

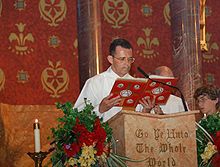

Liturgy of the Word

On Sundays and solemnities, three Scripture readings are given. On other days there are only two. If there are three readings, the first is from the Old Testament (a term wider than Hebrew Scriptures, since it includes the Deuterocanonical Books), or the Acts of the Apostles during Eastertide. The first reading is followed by a Responsorial Psalm, a complete Psalm or a sizeable portion of one. A cantor, choir or lector leads, and the congregation sings or recites a refrain. The second reading is from the New Testament, typically from one of the Pauline epistles. The reader typically concludes each reading by proclaiming that the reading is "the word of the Lord," and congregation responds by saying "Thanks be to God."

The final reading and high point of the Liturgy of the Word is the proclamation of the Gospel. This is preceded by the singing or recitation of the Gospel Acclamation, typically an Alleluia with a verse of Scripture, which may be omitted if not sung. Alleluia is replaced during Lent by a different acclamation of praise. All stand while the Gospel is chanted or read by a deacon or, if none is available, by a priest. To conclude the Gospel reading, the priest or deacon proclaims: "This is the Gospel of the Lord" (in the United States, "The Gospel of the Lord") and the people respond, "Praise to you, Lord Jesus Christ." The priest or deacon then kisses the book.

At least on Sundays and Holy Days of Obligation, a homily, a sermon that draws upon some aspect of the readings or the liturgy of the day, is then given. Ordinarily the priest celebrant himself gives the homily, but he may entrust it to a concelebrating priest or, occasionally, to the deacon, but never to a lay person. In particular cases and for a just cause, a bishop or priest who is present but unable to concelebrate may give the homily. On days other than Sundays and Holy Days of Obligation, the homily, though not obligatory, is recommended.[14]

On Sundays and solemnities, all then profess their Christian faith by reciting or singing the Nicene Creed or, especially from Easter to Pentecost, the Apostles' Creed, which is particularly associated with baptism and often used with Masses for children.

The Liturgy of the Word concludes with the General Intercessions or "Prayers of the Faithful." The priest speaks a general introduction, then a deacon or lay person addresses the congregation, presenting some intentions for prayer, to which the congregation responds with a short response such as: "Lord hear our prayer". The priest may conclude with a supplication.

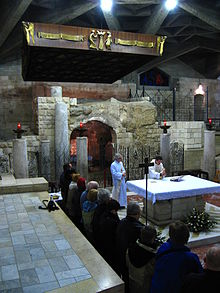

Liturgy of the Eucharist

The linen corporal is spread over the center of the altar, and the Liturgy of the Eucharist begins with the ceremonial placing on it of bread and wine. These may be brought to the altar in a procession, especially if Mass is celebrated with a large congregation.[15] The bread (wheaten and unleavened) is placed on a paten, and the wine (from grapes), mixed with a little water, is put in a chalice. As the priest places each on the corporal, he says a silent prayer over each individually, which, if this rite is unaccompanied by singing, he is permitted to say aloud, in which case the congregation responds to each prayer with: "Blessed be God forever." Then the priest washes his hands, "a rite that is an expression of his desire for interior purification."[16]

The congregation, which has been seated during this preparatory rite, rises, and the priest gives an exhortation to pray: "Pray, brethren, that our sacrifice may be acceptable to God, the almighty Father." The congregation responds: "May the Lord accept the sacrifice at your hands, for the praise and glory of his name, for our good, and the good of all his Church." The priest then pronounces the variable prayer over the gifts that have been set aside.

The Eucharistic Prayer, "the center and summit of the entire celebration",[17] then begins with a dialogue between priest and people. This dialogue opens with the normal liturgical greeting, but in view of the special solemnity of the rite now beginning, the priest then exhorts the people: "Lift up your hearts." The people respond with: "We lift them up to the Lord." The priest then introduces the great theme of the Eucharist, a word originating in the Greek word for giving thanks: "Let us give thanks to the Lord, our God," he says. The congregation joins in this sentiment, saying: "It is right to give him thanks and praise."

The priest then continues with one of many Eucharistic Prayer prefaces, which lead to the Sanctus acclamation: "Holy, Holy, Holy Lord God of power and might, Heaven and Earth are full of your glory, Hosanna in the Highest, Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord, Hosanna in the Highest."

In some countries, including the United States, the people kneel immediately after the singing or recitation of the Sanctus. However, the general rule is that they kneel somewhat later, for the Consecration,[18] when, according to Catholic faith, the whole substance (what they are prior to the consecration) of the bread and wine is converted into that of the body and blood of Christ (which are now inseparable from one another and from his soul and divinity),[19] while the accidents (or appearances) of bread and wine remain unaltered (see Transubstantiation).

The Eucharistic Prayer includes the Epiclesis, through which the Church implores the power of the Holy Spirit that the gifts that have been set aside may become Christ's body and blood and that the Communion may be for the salvation of those who will partake of it.[20]

The central part is the Institution Narrative and Consecration, recalling the words and actions of Jesus at his Last Supper, which he told his disciples to do in remembrance of him.[21]

Immediately after the Consecration and the display to the people of the consecrated elements, the priest invites the people to proclaim "the mystery of faith", and the congregation joins in reciting the Memorial Acclamation. The Roman Missal gives three forms of this acclamation. Of the first of these three, the 1973 English translation provided a very loose translation and added a second not based on any of the Latin acclamations. In Ireland yet another form ("My Lord and my God") was permitted. The revised translation, which will be put into use in most English-speaking countries on the first Sunday in Advent in 2011 (it is already in use in South Africa) has instead faithful translations of the three Latin acclamations.[22]

The Eucharistic Prayer also includes the Anamnesis, expressions of offering, and intercessions for the living and dead.

It concludes with a doxology, with the priest lifting up the paten with the host and the deacon (if there is one) the chalice, and the singing or recitation of the Amen by the people. The unofficial term "The Great Amen" is sometimes applied to this Amen.

| Part of a series on the |

| Catholic Church |

|---|

|

| Overview |

|

|

Communion rite

All together recite or sing the "Lord's Prayer" ("Pater Noster" or "Our Father"). The priest introduces it with a short phrase and follows it up with the embolism: "Deliver us, Lord, from every evil, and grant us peace in our day. In your mercy keep us free from sin and protect us from all anxiety as we wait in joyful hope for the coming of our Savior, Jesus Christ." The people then add the doxology: "For the kingdom, the power, and the glory are yours, now and forever."

Next comes the rite of peace (pax). After praying: "Lord Jesus Christ, you said to your apostles: 'I leave you peace, my peace I give you.' Look not on our sins, but on the faith of your Church, and grant us the peace and unity of your kingdom where you live for ever and ever ", the priest wishes the people the peace of Christ: "The peace of the Lord be with you always." The deacon or, in his absence, the priest may then invite those present to offer each other the sign of peace. The form of the sign of peace varies according to local custom for a respectful greeting (for instance, a handshake or a bow between strangers, or a kiss/hug between family members).

While the "Lamb of God" ("Agnus Dei" in Latin) litany is sung or recited, the priest breaks the host and places a piece in the main chalice; this is known as the rite of fraction and commingling.

If extraordinary ministers of Holy Communion are required, they may come forward at this time, but they are not allowed to go to the altar itself until after the priest has received Communion (General Instruction of the Roman Missal, 162). The priest then presents the transubstantiated elements to the congregation, saying: "This is the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world. Happy are those who are called to his supper." Then all repeat: "Lord, I am not worthy to receive you, but only say the word and I shall be healed." The priest then receives Communion and, with the help, if necessary, of extraordinary ministers, distributes Communion to the people, who, as a rule,[23] approach in procession. When receiving Holy Communion, the communicant bows his or her head before the Sacrament as a gesture of reverence, and may receive the consecrated host either on the tongue or in the hand, at the discretion of each communicant.[23] The distributing minister says: "The body of Christ" or "The blood of Christ", according as the element distributed is the consecrated bread or the consecrated wine, or: "The body and blood of Christ", if both are distributed together (by intinction).[24] The communicant responds: "Amen."

While Communion is distributed, an appropriate song is recommended. If that is not possible, a short antiphon is recited before the distribution begins.

"The sacred vessels are purified by the priest, the deacon, or an instituted acolyte after Communion or after Mass, insofar as possible at the credence table" (GIRM 279). Then the priest concludes the Liturgy of the Eucharist with the Prayer after Communion, for which the people are invited to stand.

Concluding rite

After the Prayer after Communion, announcements may be made. The Missal says these should be brief. The priest then gives the usual liturgical greeting and imparts his blessing. The liturgy concludes with a dialogue between the priest and congregation. The deacon, or in his absence, the priest himself then dismisses the people. The Latin formula is simply "Ite, missa est", but the 1973 English Missal gives a choice of dismissal formulas. The congregation responds: "Thanks be to God." The priest and other ministers then leave, often to the accompaniment of a recessional hymn, and the people then depart. In some countries the priest customarily stands outside the church door to greet them individually.

Time of celebration of Mass

Since the Second Vatican Council, the time for fulfilling the obligation to attend Mass on Sunday or a Holy Day of Obligation now begins on the evening of the day before,[25][26] and most parish churches do celebrate the Sunday Mass also on Saturday evening. By long tradition and liturgical law, Mass is not celebrated at any time on Good Friday (but Holy Communion is distributed, with hosts consecrated at the evening Mass of the Lord's Supper on Holy Thursday, to those participating in the Celebration of the Passion of the Lord) or on Holy Saturday before the Easter Vigil (the beginning of the celebration of Easter Sunday), in other words, between the annual celebrations of the Lord's Supper and the Resurrection of Jesus (see Easter Triduum).

Deacons, priests and bishops are required to celebrate the Liturgy of the Hours daily, but are not obligated to celebrate Mass daily. "Apart from those cases in which the law allows him to celebrate or concelebrate the Eucharist a number of times on the same day, a priest may not celebrate more than once a day" (canon 905 of the Code of Canon Law), and "a priest may not celebrate the Eucharistic Sacrifice without the participation of at least one of the faithful, unless there is a good and reasonable cause for doing so" (canon 906).

Priests may be required by their posts to celebrate Mass daily, or at least on Sundays, for the faithful in their pastoral care. The bishop of a diocese and the pastor of a parish are required to celebrate or arrange for another priest to celebrate, on every Sunday or Holy Day of Obligation, a Mass "pro populo" - that is, for the faithful entrusted to his care.

For Latin-Rite priests, there are a few general exceptions to the limitation to celebrate only one Mass a day (General Instruction of the Roman Missal, 204). By very ancient tradition, they may celebrate Mass three times at Christmas (the Midnight Mass or "Mass of the Angels", the Dawn Mass or "Shepherd's Mass", and the Day Mass or "Mass of the Divine Word", each of which has its own readings and chants).

On All Souls' Day they may also, on the basis of a privilege to all priests by Pope Benedict XV in August 1915, celebrate Mass three times; only one of the three Masses may be for the personal intentions of the priest, while the other two Masses must be applied, one for all the faithful departed, the other for the intentions of the Pope. A priest who has concelebrated the Chrism Mass, which may be held on the morning of Holy Thursday, may also celebrate or concelebrate the Mass of the Lord's Supper that evening. A priest may celebrate or concelebrate both the Mass of the Easter Vigil and Mass during Easter day (the Easter Vigil "should not begin before nightfall; it should end before daybreak on Sunday"; and may therefore take place at midnight or in the early hours of Easter morning). Finally, a priest who has concelebrated Mass at a meeting of priests or during a pastoral visitation by a bishop or a bishop's delegate, may celebrate a second Mass for the benefit of the laity.

In addition to these general permissions, the Local Ordinary may, for a good reason, permit priests to celebrate twice (they are then said to "binate," and the act is "bination") on weekdays, and three times ("trinate," and "trination") on Sundays and Holy Days (canon 905 §2). Examples would be: if a parish priest were to need to celebrate the usual, scheduled daily Mass of a parish, and a funeral later in the morning, or three Masses to accommodate all of the parishioners in a very populous parish on Sundays. In particularly difficult circumstances, the Pope can grant the diocesan bishop permission to give his priests faculties to trinate on weekdays and quadrinate on Sundays.

In many countries, the bishop's power to permit priests to celebrate two Masses on one day and three Masses on one day is widely availed of, so that it is common for priests assigned to parish ministry to celebrate at least two Masses on any given Sunday, and two Masses on several other days of the week. Permission for four Masses on one day has been obtained in order to cope with large numbers of Catholics either in mission lands or where the ranks of priests are diminishing.

Summary table

| Situation | Masses permitted | Masses required |

|---|---|---|

| Normal weekday | 1 | 0 |

| Normal Sunday | 2 | 1 |

| All Souls' Day | 3 | 1 |

| Christmas Day | 3 | 1 |

| Easter | 2 | 1 |

| Holy Thursday | 2 | 1 |

| Weekday with permission of Local Ordinary | 2 | 0 |

| Sunday or Holy Day with permission of Local Ordinary | 3 | 1 |

| Weekday with permission of the Pope through Local Ordinary | 3 | 0 |

| Sunday or Holy Day with permission of the Pope through Local Ordinary | 4 | 1 |

Duration of the celebration

The length of time that it takes to celebrate Mass varies considerably. While the Roman Rite liturgy is shorter than other liturgical rites, it may on solemn occasions - even apart from exceptional circumstances such as the Easter Vigil or an event such as ordinations - take over an hour and a half. The length of the homily is an obvious factor that contributes to the overall length. Other factors are the number of people receiving Communion and the number and length of the chants and other singing.

For most of the second millennium, before the twentieth century brought changes beginning with Pope Pius X's encouragement of frequent Communion, the usual Mass was said exactly the same way whether people other than a server were present or not. No homily was given,[27] and most often only the priest himself received Communion.[28] Moral theologians gave their opinions on how much time the priest should dedicate to celebrating a Mass, a matter on which canon law and the Roman Missal were silent. One said that an hour should not be considered too long. Several others that, in order to avoid tedium, Mass should last no more than half an hour; and in order to be said with due reverence, it should last no less than twenty minutes. Another theologian, who gave half an hour as the minimum time, considered that Mass could not be said in less than a quarter of an hour, an opinion supported by others, including Saint Alphonsus Liguori, who said that any priest who finished Mass in less than that time could scarcely be excused from mortal sin.[29]

Special Masses

Ritual Masses

A Mass celebrated in connection with a particular rite, such as an ordination, a wedding or a profession of religious vows, may use texts provided in the "Ritual Masses" section of the Roman Missal. The rite in question is, most often, a sacrament, but the section has special texts not only for Masses within which Baptism, Confirmation, Anointing of the Sick, Orders, and Holy Matrimony are celebrated, but also for Masses with religious profession, the dedication of a church, and several other rites. Confession (Penance or Reconciliation) is the only sacrament not celebrated within a Eucharistic framework and for which therefore no Ritual Mass is provided.

The Ritual Mass texts may not be used, except perhaps partially, when the rite is celebrated during especially important liturgical seasons or on high ranking feasts.

A Nuptial Mass[30] is a Ritual Mass within which the sacrament of Holy Matrimony is celebrated. If one of a couple being married in a Catholic church is not a Catholic, the rite of Holy Matrimony outside Mass is to be followed. However, if the non-Catholic has been baptized in the name of all three Persons of the Trinity (and not only in the name of, say, Jesus, as is the baptismal practice in some branches of Christianity), then, in exceptional cases and provided the bishop of the diocese gives permission, it may be considered suitable to celebrate the marriage within Mass, except that, according to the general law, Communion is not given to the non-Catholic (Rite of Marriage, 8).

Mass in Anglicanism

"Mass" is one of many terms used to describe the Eucharist in the Anglican tradition, the others being "Holy Communion," "Holy Eucharist," "the Lord's Supper," and "the Divine Liturgy."[31] In the English-speaking Anglican world, the term used frequently connotes the Eucharistic theology of the one using it. "Mass" is considered an Anglo-Catholic term.

Structure of the rite

The various Eucharistic liturgies used by national churches of the Anglican Communion have continuously evolved from the early editions of the Book of Common Prayer, which was loosely based upon the Pre-Tridentine Mass. The structure of the liturgies, crafted in the tradition of the Elizabethan Settlement, allows for a variety of theological interpretations, and generally follows the same rough shape. Some or all of the following elements may be altered or absent depending on the rite, the liturgical season and use of the province or national church:

- The Gathering of the Community: Beginning with a Trinitarian-based greeting or seasonal acclamation; followed by the Collect for Purity; the Gloria in Excelsis Deo or some other song of praise, Kyrie eleison, and/or Trisagion; and then the collect of the day. During Lent and/or Advent especially, this part of the service may begin or end with a penitential rite.

- The Proclamation of the Word: Usually two to three readings of Scripture, one of which is always from the Gospels, plus a psalm (or portion thereof) or canticle between the lessons. This is followed by a sermon or homily; the recitation of the Apostles', Nicene or Athanasian Creeds; the prayers of the congregation or a general intercession, a general confession and absolution, and the passing of the peace.

- The Celebration of the Eucharist: The gifts of bread and wine are brought up, along with other gifts (such as money and/or food for a food bank, etc.), and an offertory prayer is recited. Following this, a Eucharistic Prayer (called "The Great Thanksgiving") is offered. This prayer consists of a dialogue (the Sursum Corda), a preface, the sanctus and benedictus, the Words of Institution, the Anamnesis, an Epiclesis a petition for salvation and a Doxology. The Lord's Prayer precedes the fraction (the breaking of the bread), followed by the Prayer of Humble Access and/or the Agnus Dei, and the distribution of the sacred elements (the bread and wine). After all who have desired to have received, there is a post-Communion prayer, which is a general prayer of thanksgiving. The service concludes with a Trinitarian blessing and the dismissal.

The liturgy is divided into two parts: The Liturgy of the Word and the Liturgy of the Eucharist, but the entire liturgy itself is also properly referred to as the Holy Eucharist. The parts and sequence of the liturgy are almost identical to the Roman Rite, except the Confession of Sin ends the Liturgy of the Word in the Anglican rites in North America, while in the Roman Rite and in Anglican rites in the rest of the world the Confession is near the beginning of the service.

Special masses

The Anglican tradition includes separate rites for nuptial masses, funeral masses, and votive masses. The Eucharist is an integral part of many other sacramental services, including ordination and Confirmation.

Ceremonial

A few Anglo-Catholic parishes use Anglican versions of the Tridentine Missal, such as the English Missal, The Anglican Missal, or American Missal, for the celebration of mass, all of which are intended primarily for the celebration of the Eucharist. Many Anglo-Catholic parishes in the Church of England use A Manual of Anglo-Catholic Devotion (successor to the earlier A Manual of Catholic Devotion). In the Episcopal Church USA, a traditional-language, Anglo-Catholic adaptation of the 1979 Book of Common Prayer has been published (An Anglican Service Book).

All of these books contain such features as meditations for the presiding celebrant(s) during the liturgy, and other material such as the rite for the blessing of palms on Palm Sunday, propers for special feast days, and instructions for proper ceremonial order. These books are used as a more expansively Catholic context in which to celebrate the liturgical use found in the Book of Common Prayer and related liturgical books.

These are supplemented by books specifying ceremonial actions, such as A Priest's Handbook by David Michno, Ceremonies of the Eucharist, by Howard E. Galley, and Ritual Notes by E.C.R. Lamburn. Other guides to ceremonial include the General Instruction of the Roman Missal, Ceremonies of the Modern Roman Rite (Peter Elliott), Ceremonies of the Roman Rite Described (Adrian Fortescue), and The Parson's Handbook (Percy Dearmer).

Mass in Lutheranism

In the Book of Concord, Article XXIV ("Of the Mass") of the Augsburg Confession (1530) begins thus: "Falsely are our churches accused of abolishing the Mass; for the Mass is retained among us, and celebrated with the highest reverence. We do not abolish the Mass but religiously keep and defend it... we keep the traditional liturgical form... In our churches Mass is celebrated every Sunday and on other holy days, when the sacrament is offered to those who wish for it after they have been examined and absolved (Article XXIV)".

Martin Luther rejected parts of the Roman Rite Catholic Mass (specifically the Canon of the Mass), which he argued did not conform with Hebrews 7:27, which contrasts the Old Testament priests, who needed to make a sacrifice for sins on a regular basis, with the single priest Christ, who offers his body only once as a sacrifice, and also with Hebrews 9:26, 9:28, and 10:10. He composed as a replacement a revised Latin-language rite, Formula missae in 1523 and the vernacular Deutsche Messe in 1526.

In German, the Scandinavian languages, Finnish, and some English Lutherans, use the word "Mass" for their corresponding service,[32] but in most English-speaking churches, they call it the "Divine Service", "Holy Communion, or "the Holy Eucharist".

The celebration of the Mass in Lutheran churches follows a similar pattern to other traditions, starting with public confession (Confiteor) by all and a Declaration of Grace said by the priest or pastor. Followed by the Introit, Kyrie, Gloria, collect, the readings with an alleluia (alleluia is not said during Lent), homily (or sermon) and recitation of the Nicene Creed. The Service of the Eucharist includes the General intercessions, Preface, Sanctus and Eucharistic Prayer, elevation of the host and chalice and invitation to the Eucharist. The Agnus Dei is chanted while the clergy and assistants first commune followed by lay communicants. Postcommunion prayers and the final blessing by the priest ends the Mass. A Roman Catholic or Anglican would find its elements familiar, in particular the use of the sign of the cross, kneeling for prayer and the Eucharistic Prayer, bowing to the processional crucifix, kissing the altar, incense (among some), chanting, and vestments.

Lutherans are to offer the Eucharist each Sunday.[33] Also, eucharistic ministers take the sacramental elements to the sick in hospitals and nursing homes. The ancient practice of celebrating Mass each Sunday is as Martin Luther wanted and the Lutheran confessions teach is increasingly the norm in most Lutheran parishes throughout the world. This restoration of the weekly Mass has been strongly encouraged by the bishops and priests/pastors.

The celebration of the Eucharist may be included in weddings, funerals, retreats, the dedication of a church building and at annual synod conventions. The Mass is also an important aspect of ordinations and confirmations in Lutheran churches.

See also

- Mass (music)

- Mass of Paul VI

- Eucharistic theologies contrasted

- Pontifical High Mass

- Gnostic Mass

- Chantry

- Red Mass

- Requiem

References

- ^ Missa here is a Late Latin substantive corresponding to the word missio in classical Latin.

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Council of Trent, Session 22, Chapter I

- ^ Catechism of Catholic Church paragraph 1324

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1374-1376

- ^ "The Missal published by Paul VI and then republished in two subsequent editions by John Paul II, obviously is and continues to be the normal Form – the Forma ordinaria – of the Eucharistic Liturgy" Letter of Pope Benedict to the Bishops, 7 July 2007, paragraph 5

- ^ General Instruction of the Roman Missal, 44

- ^ "The antiphon and Psalm from the Graduale Romanum or the Graduale Simplex may be used or another song that ... has a text approved by the Conference of Bishops" (General Instruction of the Roman Missal, 48).

- ^ General Instruction of the Roman Missal, 48

- ^ The Order of Mass

- ^ Basic Texts for the Catholic Mass

- ^ The Holy Mass

- ^ Introductory Rites

- ^ General Instruction of the Roman Missal, 66

- ^ "It is praiseworthy for the bread and wine to be presented by the people" (GIRM, 73).

- ^ GIRM, 76

- ^ GIRM, 78

- ^ "They should kneel at the consecration, except when prevented on occasion by reasons of health, lack of space, the large number of people present, or some other good reason. Those who do not kneel ought to make a profound bow when the priest genuflects after the consecration" (General Instruction of the Roman Missal, 43).

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ General Instruction of the Roman Missal, 79c

- ^ Luke 22:19; 1 Corinthians 11:24–25

- ^ The Order of Mass

- ^ a b GIRM, 160

- ^ GIRM, 287

- ^ " Each Sunday and Solemnity (major celebration) begins on the evening of the day before with Evening Prayer I (First Vespers)" (The Liturgical Calendar and the Liturgy of the Hours); cf. What Time for Anticipated Masses?

- ^ Letter De Missa vespere sabbati of the Congregation of Rites dated Sept 25 1965, in Enchiridion Documentorum Instaurationis Liturgicae, vol I, n. 35

- ^ Preaching was generally done outside Mass. The Ritus servandus in celebratione Missae of the Tridentine Missal mentions preaching at Mass only in connection with Solemn Mass (in section VI, 60) and only as a possibility.

- ^ Gerald Ellard, S.J., Ph.D.: Christian Life and Worship, chapter XI

- ^ St Alphonus Liguori: Sacerdos Sanctificatus. Discourses on the Mass and Office. Translated by Rev. James Jones. London 1846 pages 30-33

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ "The Catechism (1979 Book of Common Prayer): The Holy Eucharist".

- ^ Nicholas Hope, German and Scandinavian Protestantism, 1700 to 1918 (Oxford University Press 1995 ISBN 0-19-826994-3), p. 18; see also Deutsche Messe

- ^ Why Commune Every Sunday?. Retrieved 2010-18-01

Further reading

- Baldovin,SJ, John F., (2008). Reforming the Liturgy: A Response to the Critics. The Liturgical Press.

- Bugnini, Annibale (Archbishop), (1990). The Reform of the Liturgy 1948-1975. The Liturgical Press.

- Donghi, Antonio, (2009). Words and Gestures in the Liturgy. The Liturgical Press.

- Foley, Edward,. From Age to Age: How Christians Have Celebrated the Eucharist, Revised and Expanded Edition. The Liturgical Press.

- Fr. Nikolaus Gihr (1902). The Holy Sacrifice of the Mass: Dogmatically, Liturgically, and Ascetically Explained. St. Louis: Freiburg im Breisgau. OCLC 262469879. Retrieved 20-04-2011.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - Johnson, Lawrence J., (2009). Worship in the Early Church: An Anthology of Historical Sources. The Liturgical Press.

- Marini, Piero (Archbishop), (2007). A Challenging Reform: Realizing the Vision of the Liturgical Renewal. The Liturgical Press.

- Martimort, A.G. (editor). The Church At Prayer. The Liturgical Press.

External links

Roman Catholic doctrine

- Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1322-1419

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Why Fast Before Communion? by Fr. William Saunders

- Catholic Apologetics of America

- Links to documents on the Mass

- Celebrate The Liturgy

Present form of the Roman rite of the Mass

- The Order of Mass

- Fr. Larry Fama's Instructional Mass

- Today's Mass readings (New American Bible version)

- The Readings of the Mass (Jerusalem Bible version)

- Mass Readings (text in official Lectionary for Ireland, Australia, Britain, New Zealand etc.)

- Forum about Liturgy

Tridentine form of the Roman rite of the Mass

- Latin Mass § CatholicLatinMass.org

- SanctaMissa.org: Multimedia Tutorial on the Latin Mass

- The Holy Mass: A Pictorial Guide with Text

- Text of the Tridentine Mass in Latin and English

(For links on Post-Tridentine vs. "Tridentine" controversy, see Mass of Paul VI)

Anglican Doctrine and practice

Lutheran doctrine

- Article 24 of the Augsburg Confession, regarding the Mass

- Article 23 of the Defense of the Augsburg Confession, regarding the Mass

- The Church of Sweden Service Book including the orders for High and Low Mass