Green economy

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

No issues specified. Please specify issues, or remove this template. |

| Part of a series about |

| Environmental economics |

|---|

|

A green economy is one that results in improved human well-being and social equity, while significantly reducing environmental risks and ecological scarcities - United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) (2010). A green economy is a economy or economic development model based on sustainable development and a knowledge of ecological economics.

Its most distinguishing feature from prior economic regimes is direct valuation of natural capital and nature's services as having economics value (see TEEB and Bank of Natural Capital) and a full cost accounting regime in which costs externalized onto society via ecosystems are reliably traced back to, and accounted for as liabilities of, the entity that does the harm or neglects an asset.

"Green" economists and economics

A green economics loosely defined is any theory of economics by which an economy is considered to be component of the ecosystem in which it resides (after Lynn Margulis). A holistic approach to the subject is typical, such that economic ideas are commingled with any number of other subjects, depending on the particular theorist. Proponents of feminism, postmodernism, the ecology movement, peace movement, Green politics, green anarchism and anti-globalization movement have used the term to describe very different ideas, all external to some equally ill-defined "mainstream" economics.

The use of the term is further ambiguated by the political distinction of Green parties which are formally organized and claim the capital-G "Green" term as a unique and distinguishing mark. It is thus preferable to refer to a loose school of "'green economists"' who generally advocate shifts towards a green economy, biomimicry and a fuller accounting for biodiversity. (see TEEB especially for current authoritative international work towards these goals and Bank of Natural Capital for a layman's presentation of these.)

Some economists view green economics as a branch or subfield of more established schools. For instance, as classical economics where the traditional land is generalized to natural capital and has some attributes in common with labor (providing nature's services to man) and physical capital (since natural capital assets like rivers directly substitute for man-made ones such as canals). Or, as Marxist economics with nature represented as a form of lumpen proletariat, an exploited base of non-human workers providing surplus value to the human economy. Or as a branch of neoclassical economics in which the price of life for developing vs. developed nations is held steady at a ratio reflecting a balance of power and that of non-human life is very low.

An increasing consensus around the ideas of nature's services, natural capital, full cost accounting and interspecies ethics[clarification needed] could blur distinctions between the schools and redefine them all as variations of green economics. As of 2010 the Bretton Woods institutions (notably the World Bank [1] and IMF (via its "Green Fund" initiative) responsible for global monetary policy have stated a clear intention to move towards biodiversity valuation and a more official and universal biodiversity finance. Taking these into account targeting not less but radically zero emission and waste is what is promoted by the Zero Emissions Research and Initiatives.

Definition of a green economy

Karl Burkart defines a green economy as based on six main sectors:[1]

- Renewable energy (solar, wind, geothermal, marine including wave, biogas, and fuel cell)

- Green buildings (green retrofits for energy and water efficiency, residential and commercial assessment; green products and materials, and LEED construction)

- Clean transportation (alternative fuels, public transit, hybrid and electric vehicles, carsharing and carpooling programs)

- Water management (Water reclamation, greywater and rainwater systems, low-water landscaping, water purification, stormwater management)

- Waste management (recycling, municipal solid waste salvage, brownfield land remediation, Superfund cleanup, sustainable packaging)

- Land management (organic agriculture, habitat conservation and restoration; urban forestry and parks, reforestation and afforestation and soil stabilization)

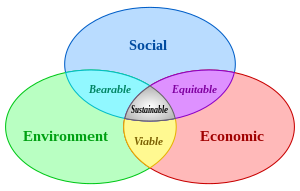

The Global Citizens Center, led by Kevin Danaher, defines green economy in terms of a "triple bottom line," an economy concerned with being:[2]

- Environmentally sustainable, based on the belief that our biosphere is a closed system with finite resources and a limited capacity for self-regulation and self-renewal. We depend on the earth’s natural resources, and therefore we must create an economic system that respects the integrity of ecosystems and ensures the resilience of life supporting systems.

- Socially just, based on the belief that culture and human dignity are precious resources that, like our natural resources, require responsible stewardship to avoid their depletion. We must create a vibrant economic system that ensures all people have access to a decent standard of living and full opportunities for personal and social development.

- Locally rooted, based on the belief that an authentic connection to place is the essential pre-condition to sustainability and justice. The Green Economy is a global aggregate of individual communities meeting the needs of its citizens through the responsible, local production and exchange of goods and services.

Other issues

Green economy includes green energy generation based on renewable energy to substitute for fossil fuels and energy conservation for efficient energy use. The green economy creates jobs, ensures real, sustainable economic growth, and prevents environmental pollution, global warming, resource depletion, and environmental degradation[citation needed].

Because the market failure related to environmental and climate protection as a result of external costs, high future commercial rates and associated high initial costs for research, development, and marketing of green energy sources and green products prevents firms from being voluntarily interested in reducing environment-unfriendly activities (Reinhardt, 1999; King and Lenox, 2002; Wagner, 203; Wagner, et al., 2005), the green economy may need government subsidies as market incentives to motivate firms to invest and produce green products and services. The German Renewable Energy Act, legislations of many other EU countries and the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, all provide such market incentives.

However, there are still incompatibilities between the UN global green new deal call and the existing international trade mechanism in terms of market incentives[citation needed]. For example, the WTO Subsidies Agreement has strict rules against government subsidies, especially for exported goods[original research?]. Such incompatibilities may serve as obstacles to governments' responses to the UN Global green new deal call.

See also

- Agroecology

- Alternative energy indexes

- Ecology of contexts

- Embodied energy

- Embodied water

- Energy accounting

- Energy economics

- Energy policy

- Energy quality

- Environmental economics

- Environmental ethics

- Exergy

- Feed-in tariff

- Green accounting

- Human development theory

- Human ecology

- ISO 14000

- Industrial ecology

- List of Green topics

- Natural capital

- Natural resource economics

- Passive solar building design

- Renewable energy commercialization

- Renewable heat

- Sustainable design

- The Clean Tech Revolution

- The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity (TEEB)

- World energy resources and consumption

Notes

References

- Cato, M. S. (2009), Green Economics: An Introduction to Theory, Policy and Practice. London: Earthscan.

- Common, M. and Stagl, S. 2005. Ecological Economics: An Introduction. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Daly, H. and Townsend, K. (eds.) 1993. Valuing The Earth: Economics, Ecology, Ethics. Cambridge, Mass.; London, England: MIT Press.

- Georgescu-Roegen, N. 1975. Energy and economic myths. Southern Economic Journal 41: 347-381.

- Hahnel, R. (2010), Green Economics: Confronting the Ecological Crisis. New York: M. E. Sharpe.

- Kennet M., and Heinemann V, (2006) Green Economics, Setting the Scene. in International Journal of Green Economics, Vol 1 issue 1/2 (2006)

Inderscience.Geneva

- Kennet M., (2009) Emerging Pedogogy in an Emerging Discipline, Green Economics in Reardon J., (2009) Pluralist education, Routledge.

- Kennet M., (2008) Introduction to Green Economics, in Harvard School Economics Review.

- King, Andrew; Lenox, Michael, 2002. ‘Does it really pay to be green?’ Journal of Industrial Ecology 5, 105-117.

- Krishnan R, Harris JM, Goodwin NR. (1995). A Survey of Ecological Economics. Island Press. ISBN 1559634111, 9781559634113.

- Martinez-Alier, J. (1990) Ecological Economics: Energy, Environment and Society. Oxford, England: Basil Blackwell.

- Martinez-Alier, J., Ropke, I. eds.(2008), Recent Developments in Ecological Economics, 2 vols., E. Elgar, Cheltenham, UK.

- Røpke, I. (2004) The early history of modern ecological economics. Ecological Economics 50(3-4): 293-314.

- Røpke, I. (2005) Trends in the development of ecological economics from the late 1980s to the early 2000s. Ecological Economics 55(2): 262-290.

- Reinhardt, F. (1999) ‘Market failure and the environmental policies of firms: economic rationales for ‘beyond compliance’ behavior.’ Journal of Industrial Ecology 3(1), 9-21.

- Spash, C. L. (1999) The development of environmental thinking in economics. Environmental Values 8(4): 413-435.

- Vatn, A. (2005) Institutions and the Environment. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar

- United Nations Environment Programme (2010), Green Economy Report: A Preview. http://www.unep.org/GreenEconomy/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=JvDFtjopXsA%3d&tabid=1350&language=en-US

- United Nations Environment Programme (2010), Developing Countries Success Stories. http://www.unep.org/pdf/GreenEconomy_SuccessStories.pdf

- United Nations Environment Programme (2010), A Brief for Policymakers on the Green Economy and Millennium Development Goals. http://www.unep.org/greeneconomy/Portals/30/docs/policymakers_brief_GEI&MDG.pdf

- United Nations Environment Programme (2010), Driving a Green Economy Through Public Finance and Fiscal Policy Reform. http://www.unep.org/greeneconomy/Portals/30/docs/DrivingGreenEconomy.pdf

- United Nations Environment Programme (2009), Global Green New Deal Update, http://www.unep.org/greeneconomy/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=ciH9RD7XHwc%3d&tabid=1394&language=en-US

- United Nations Environment Programme (2009), Global Green New Deal, Policy brief, http://www.unep.org/pdf/A_Global_Green_New_Deal_Policy_Brief.pdf

- United Nations Environment Programme (2008), Green Jobs: Towards Decent Work in a Sustainable, Low-Carbon World (Policy messages and main findings for decision makers), http://www.unep.org/greeneconomy/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=hR62Ck7RTX4%3d&tabid=1377&language=en-US

- United Nations Environment Programme (2008), ‘Global green new deal - environmentally-focused investment historic opportunity for 21st century prosperity and job generation.’ London/Nairobi, October 22.

- Wagner, Ma. (2003) "Does it pay to be eco-efficient in the European energy supply industry?" Zeitschrift für Energiewirtschaft 27(4), 309-318.

- Wagner, M. et al. (2002) "The relationship between environmental and economic performance of firms: what does the theory propose and what does the empirical evidence tell us?" Greener Management International 34, 95-108.

External links

- The Green Economy Coalition http://www.greeneconomycoalition.org

- http://www.2tix.net/zone/edit_page2.php The Green Economist

- UNEP – The Green Economy Initiative, http://www.unep.org/greeneconomy

- The 2012 Earth Summit http://www.earthsummit2012.org/

- The Green Economics Institute - http://greeneconomics.org.uk/

- The Green Economics Institute Global Campaigning Forum - http://greeneconomicsinstitute.wordpress.com/

- The International Society for Ecological Economics (ISEE) - http://www.ecoeco.org/

- Green Recovery - http://www.americanprogress.org/issues/2008/09/green_recovery.html

- The International Journal of Green Economics, http://www.inderscience.com/ijge

- Eco-Economy Indicators: http://www.earth-policy.org/Indicators/index.htm

- EarthTrends World Resources Institute - http://earthtrends.wri.org/index.php

- The Inspired Economist.

- Ecological Economics Encyclopedia - http://www.ecoeco.org/education_encyclopedia.php

- The academic journal, Ecological Economics - http://www.elsevier.com/locate/ecolecon

- The US Society of Ecological Economics - http://www.ussee.org/

- The Beijer International Institute for Ecological Economics - http://www.beijer.kva.se/

- Green Economist website: http://www.greeneconomist.org/

- Sustainable Prosperity - http://sustainableprosperity.ca/

- World Resources Forum - http://www.worldresourcesforum.org

- The Gund Institute of Ecological Economics - http://www.uvm.edu/giee

- Ecological Economics at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute - http://www.economics.rpi.edu/ecological.html

- An ecological economics article about reconciling economics and its supporting ecosystem - http://www.fs.fed.us/eco/s21pre.htm

- "Economics in a Full World", by Herman E. Daly - http://sef.umd.edu/files/ScientificAmerican_Daly_05.pdf

- Steve Charnovitz, "Living in an Ecolonomy: Environmental Cooperation and the GATT," Kennedy School of Government, April 1994.

- NOAA Economics of Ecosystems Data & Products – http://www.economics.noaa.gov/?goal=ecosystems