Janis Joplin

Janis Joplin | |

|---|---|

| File:Janis Lyn Joplin.jpg | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Janis Lyn Joplin |

| Genres | Blues-rock, psychedelic rock, blues, hard rock, acid-rock, soul, country, folk |

| Occupation(s) | Singer, songwriter, musician, arranger, painter, dancer |

| Instrument(s) | Vocals, guitar, autoharp, harmonica, percussion |

| Years active | 1962–1970 |

| Labels | Columbia |

| Website | officialjanis.com |

Janis Lyn Joplin (January 19, 1943 – October 4, 1970) was an American singer, songwriter, painter, dancer and music arranger. She rose to prominence in the late 1960s as the lead singer of Big Brother and the Holding Company and later as a solo artist with her backing groups, The Kozmic Blues Band and The Full Tilt Boogie Band. At the height of her career she was known as The Queen of Rock and Roll as well as The Queen of Psychedelic Soul. Rolling Stone magazine ranked Joplin number 46 on its list of the 100 Greatest Artists of All Time in 2004,[1] and number 28 on its 2008 list of 100 Greatest Singers of All Time.[2]

Early life and career: 1943–1965

Janis Joplin was born in Port Arthur, Texas, on January 19, 1943,[3] to Dorothy (née East) Joplin (1913–1998), a registrar at a business college, and her husband, Seth Joplin (1910–1987), an engineer at Texaco. She had two younger siblings, Michael and Laura. The family attended the Church of Christ.[4] The Joplins felt that Janis always needed more attention than their other children, with her mother stating, "She was unhappy and unsatisfied without [receiving a lot of attention]. The normal rapport wasn't adequate."[5]

As a teenager, she befriended a group of outcasts, one of whom had albums by African-American blues artists Bessie Smith and Leadbelly, whom Joplin later credited with influencing her decision to become a singer.[6] She began singing in the local choir and expanded her listening to blues singers such as Odetta and Big Mama Thornton.

Primarily a painter while still in school, she first began singing blues and folk music with friends. While at Thomas Jefferson High School, she stated that she was mostly shunned.[6] Joplin was quoted as saying, "I was a misfit. I read, I painted, I didn't hate niggers."[5] As a teen, she became overweight and her skin broke out so badly she was left with deep scars which required dermabrasion.[5][7][8] Other kids at high school would routinely taunt her and call her names like "pig," "freak" or "creep."[5] Among her classmates were G. W. Bailey and Jimmy Johnson.

Joplin graduated from high school in 1960 and attended Lamar State College of Technology in Beaumont, Texas, during the summer[7] and later the University of Texas at Austin, though she did not complete her studies.[9] The campus newspaper The Daily Texan ran a profile of her in the issue dated July 27, 1962 headlined "She Dares To Be Different."[9] The article began, "She goes barefooted when she feels like it, wears Levi's to class because they're more comfortable, and carries her Autoharp with her everywhere she goes so that in case she gets the urge to break into song it will be handy. Her name is Janis Joplin."[9]

Cultivating a rebellious manner, Joplin styled herself in part after her female blues heroines and, in part, after the Beat poets. Her first song recorded on tape, at the home of a fellow student in December 1962, was "What Good Can Drinkin' Do".[10] She left Texas for San Francisco ("just to get away from Texas," she said, "because my head was in a much different place"[11]) in January 1963, living in North Beach and later Haight-Ashbury. In 1964, Joplin and future Jefferson Airplane guitarist Jorma Kaukonen recorded a number of blues standards, further accompanied by Margareta Kaukonen on typewriter (as percussion instrument). This session included seven tracks: "Typewriter Talk," "Trouble In Mind," "Kansas City Blues," "Hesitation Blues", "Nobody Knows You When You're Down and Out", "Daddy, Daddy, Daddy" and "Long Black Train Blues," and was later released as the bootleg album The Typewriter Tape.

Around this time her drug use increased, and she acquired a reputation as a "speed freak" and occasional heroin user.[3][6][7] She also used other psychoactive drugs and was a heavy drinker throughout her career; her favorite beverage was Southern Comfort.

In the spring of 1965, Joplin's friends, noticing the physical effects of her amphetamine habit (she was described as "skeletal"[6] and "emaciated"[3]), persuaded her to return to Port Arthur, Texas. In May 1965, Joplin's friends threw her a bus-fare party so she could return home.[3] Back in Port Arthur, she changed her lifestyle. She avoided drugs and alcohol, began wearing relatively modest dresses, adopted a beehive hairdo, and enrolled as a sociology major at Lamar University in nearby Beaumont, Texas. During her year at Lamar University, she commuted to Austin to perform solo, accompanying herself on guitar. One of her performances was reviewed in the Austin American-Statesman. Joplin became engaged to a man who visited her, wearing a blue serge suit, to ask her father for her hand in marriage, but the man terminated plans for the marriage soon afterwards.[8]

Just prior to joining Big Brother and the Holding Company, Joplin recorded seven studio tracks in the year 1965. Among the songs she recorded was her original composition for her song Turtle Blues and an alternate version of Cod'ine by Buffy Sainte-Marie. These tracks were later issued as a new album in 1995, titled This Is Janis Joplin 1965 by James Gurley.

Big Brother and the Holding Company: 1966–1968

In 1966, Joplin's bluesy vocal style attracted the attention of the psychedelic rock band Big Brother and the Holding Company, a band that had gained some renown among the nascent hippie community in Haight-Ashbury. She was recruited to join the group by Chet Helms, a promoter who had known her in Texas and who at the time was managing Big Brother. Helms brought her back to San Francisco and Joplin joined Big Brother on June 4, 1966.[12] Her first public performance with them was at the Avalon Ballroom in San Francisco. In June she was photographed at an outdoor concert that celebrated the summer solstice. The image, which was later published in two books by David Dalton, shows her before she relapsed into drugs. Due to persistent persuading by keyboardist and close friend Stephen Ryder, Joplin avoided drug use for several weeks, enjoining bandmate Dave Getz to promise that using needles would not be allowed in their rehearsal space or in her apartment or in the homes of her bandmates whom she visited.[8] When a visitor injected drugs in front of Joplin and Getz, Joplin angrily reminded Getz that he had broken his promise.[8] A San Francisco concert from that summer was recorded and released in the 1984 album Cheaper Thrills. In July all five bandmates and guitarist James Gurley's wife Nancy moved to a house in Lagunitas, California where they lived communally. They often partied with the Grateful Dead, who lived less than two miles away.

On August 23, 1966,[13] during a four week engagement in Chicago, the group signed a deal with independent label Mainstream Records.[14] Joplin relapsed into drinking when she and her bandmates (except for Peter Albin) joined some "alcoholic hipsters," as Joplin biographer Ellis Amburn described them, in Chicago. The band recorded tracks in a Chicago recording studio, but the label owner Bob Shad refused to pay their airfare back to San Francisco.[6] Shortly after four of the five musicians drove from Chicago to Northern California with very little money (Albin traveled by plane), they returned to Lagunitas. It was there that Joplin relapsed into intravenous drug use with the encouragement of James' wife Nancy Gurley. Three years later Joplin, by then using a different band, was informed of Nancy's death from an overdose.

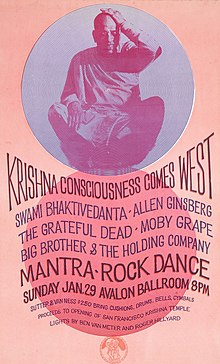

One of Joplin's earliest major performances in 1967 was the Mantra-Rock Dance, a musical event held on January 29 at the Avalon Ballroom by the San Francisco Hare Krishna temple. Janis Joplin and Big Brother performed there along with the Hare Krishna founder Bhaktivedanta Swami, Allen Ginsberg, Moby Grape, and Grateful Dead, donating proceeds to the Krishna temple.[15][16][17]

In early 1967, Joplin met Country Joe McDonald of the group Country Joe and the Fish. The pair lived together as a couple for a few months.[3][14] Joplin and Big Brother began playing clubs in San Francisco, at the Fillmore West, Winterland and the Avalon Ballroom. They also played at the Hollywood Bowl in Los Angeles, as well as in Seattle, Washington and Vancouver, British Columbia, the Psychedelic Supermarket in Boston, Massachusetts, and the Golden Bear Club in Huntington Beach, California.[14]

The band's debut album was released by Columbia Records in August 1967, shortly after the group's breakthrough appearance in June at the Monterey Pop Festival.[11] Two songs from Big Brother's set at Monterey were filmed. "Combination of the Two" and a version of Big Mama Thornton's "Ball and Chain" appear in the DVD box set of D.A. Pennebaker's documentary Monterey Pop released by The Criterion Collection. The film captured Cass Elliot, singer in The Mamas and the Papas, seated in the audience silently mouthing "Wow! That's really heavy!" during Joplin's performance of "Ball and Chain".[6] Only "Ball and Chain" was included in the film that was released to theaters nationwide in 1969 and shown on television in the 1970s. Those who did not attend Monterey Pop saw the band's performance of "Combination of the Two" for the first time in 2002 when The Criterion Collection released the box set.

After switching managers from Chet Helms to Julius Karpen in 1966, the group signed with top artist manager Albert Grossman, whom they met for the first time at Monterey Pop. For the remainder of 1967, Big Brother performed mainly in California. On February 16, 1968,[18] the group began its first East Coast tour in Philadelphia, and the following day gave their first performance in New York City at the Anderson Theater.[3][6] On April 7, 1968, the last day of their East Coast tour, Joplin and Big Brother performed with Jimi Hendrix, Buddy Guy, Joni Mitchell, Richie Havens, Paul Butterfield, and Elvin Bishop at the "Wake for Martin Luther King, Jr." concert in New York.

Live at Winterland '68, recorded at the Winterland Ballroom on April 12 and 13, 1968, features Joplin and Big Brother and the Holding Company at the height of their mutual career working through a selection of tracks from their albums. A recording became available to the public for the first time in 1998 when Sony Music Entertainment released the compact disc.

During the spring of 1968, Joplin and Big Brother made their nationwide television debut on The Dick Cavett Show, an ABC daytime variety show hosted by Dick Cavett. Shortly thereafter, network employees wiped the videotape. Over the next two years, she made three appearances on the primetime Cavett program, and all were preserved. By 1968, the band was being billed as "Janis Joplin and Big Brother and the Holding Company,"[14], and the media coverage given to Joplin incurred resentment among the other members of the band.[14] The other members of Big Brother thought that Joplin was on a "star trip," while others were telling Joplin that Big Brother was a terrible band and that she ought to dump them.[14]

TIME magazine called Joplin "probably the most powerful singer to emerge from the white rock movement," and Richard Goldstein wrote for the May 1968 issue of Vogue magazine that Joplin was "the most staggering leading woman in rock... she slinks like tar, scowls like war... clutching the knees of a final stanza, begging it not to leave... Janis Joplin can sing the chic off any listener."[5]

Cheap Thrills

For her first major studio recording, Janis played a major role in the arrangement and production of the recordings that would become Big Brother And The Holding Company's second album, Cheap Thrills. During the recording, Joplin was said to be the first person to enter the studio and the last person to leave. The album featured a cover design by counterculture cartoonist Robert Crumb. Although Cheap Thrills sounded as if it consisted of concert recordings, only "Ball and Chain" was actually recorded in front of a paying audience; the rest of the tracks were studio recordings.[3] The album had a raw quality, including the sound of a cocktail glass breaking and the broken shards being swept away during the song "Turtle Blues". Together with the premiere of the documentary film Monterey Pop at New York's Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts on December 26, 1968,[19] the album launched Joplin's successful, albeit short, musical career.[20]

Cheap Thrills reached #1 on the Billboard 200 album chart eight weeks after its release, remaining for eight (nonconsecutive) weeks.[20] The album was certified gold at release and sold over a million copies in the first month of its release.[8][14] The lead single from the album, "Piece of My Heart" reached #12 on the Billboard Hot 100 in the fall of 1968.[21]

The band made another East Coast tour during July–August 1968, performing at the Columbia Records convention in Puerto Rico and the Newport Folk Festival. After returning to San Francisco for two hometown shows at the Palace of Fine Arts Festival on August 31 and September 1, Joplin announced that she would be leaving Big Brother. On September 14, 1968, culminating a three-night final gig together at Fillmore West, fans thronged to honor and exult in the last official night of Janis Joplin with Big Brother and the Holding Company. The lead-in groups for this heady night were Chicago [[1]] (then still called Chicago Transit Authority) and Santana [[2]]. Janis gave one last performance with Big Brother at a Family Dog benefit on December 1, 1968.[3][6]

Solo career: 1969–1970

Kozmic Blues Band

After splitting from Big Brother And The Holding Company, Joplin formed a new backup group, the Kozmic Blues Band. The band was influenced by the Stax-Volt Rhythm and Blues bands of the 1960s, as exemplified by Otis Redding and the Bar-Kays.[3][6][8] The Stax-Volt R&B sound was typified by the use of horns and had a more bluesy, funky, soul, pop-oriented sound than most of the hard-rock psychedelic bands of the period.

By early 1969, Joplin was allegedly shooting at least $200 worth of heroin per day,[7] although efforts were made to keep her clean during the recording of I Got Dem Ol' Kozmic Blues Again Mama!. Gabriel Mekler, who produced the Kozmic Blues, told publicist-turned-biographer Myra Friedman after Joplin's death that the singer had lived in his house during the June 1969 recording sessions at his insistence so he could keep her away from drugs and her drug-using friends.[8]

The Kozmic Blues Band performed on many television shows with Joplin. On one episode of The Dick Cavett Show they performed "Try (Just A Little Bit Harder)" as well as "To Love Somebody". As Cavett interviewed Joplin, she admitted that she had a terrible time touring in Europe, claiming that audiences there are very uptight and don't get down. She also revealed that she was a big fan of the then unknown Tina Turner, saying that she was an incredible singer, dancer and show woman.

I Got Dem Ol' Kozmic Blues Again Mama!

The Kozmic Blues album, released in September 1969, was certified gold later that year but did not match the success of Cheap Thrills.[20] Reviews of the new group were mixed. Some music critics, including Ralph J. Gleason of the San Francisco Chronicle, were negative. Gleason wrote that the new band was a "drag" and that Joplin should "scrap" her new band and "go right back to being a member of Big Brother...(if they'll have her)."[3] Other reviewers, such as reporter Carl Bernstein of the Washington Post generally ignored the band's flaws and devoted entire articles to celebrating the singer's magic. I Got Dem Ol' Kozmic Blues Again Mama! reached #6 on the Billboard 200 weeks after it's release.

Joplin and the Kozmic Blues Band toured North America and Europe throughout 1969, appearing at Woodstock in the early morning hours of Sunday, August 17. Her friend Peggy Caserta claimed in a 1973 book that she encouraged Joplin to perform at the festival. Joplin informed her band that they would be performing at the concert as if it were just another gig. When she and the band flew by helicopter from a nearby motel to the festival site and Joplin saw the enormous crowd she instantly became incredibly nervous and giddy. The documentary film of the festival that was released to theaters the following year includes, on the left side of a split screen (filmmaking), 37 seconds of footage of Joplin and Caserta walking toward her dressing room tent.[22] By most accounts, Woodstock was not a happy affair for Joplin.[3][6][7] Faced with a ten hour wait after arriving at the backstage area, she shot heroin[6][7] with Caserta and was drinking alcohol, so by the time she hit the stage, she was "three sheets to the wind."[3] On stage her voice became slightly hoarse and wheezy and she found it hard to dance. She pulled through, however, and the audience was so pleased they cheered her on for an encore, causing her to perform Ball and Chain twice. Joplin was unhappy with her performance and blamed Caserta. Her singing was not included in the documentary film or the hit soundtrack, although the 25th anniversary director's cut of Woodstock includes her performance of "Work Me, Lord".

In addition to Woodstock, Joplin also had problems four months later at Madison Square Garden where she was joined on stage by special guests Johnny Winter and Paul Butterfield. She told rock journalist David Dalton, the audience watched and listened to "every note [she sang] with 'Is she gonna make it?' in their eyes."[14] In her interview with Dalton she added that she felt most comfortable performing at small, cheap venues in San Francisco that were associated with the counterculture. At the time of this June 1970 interview she already had performed in the Bay Area for what turned out to be the last time.

Sam Andrew, the lead guitarist who had left Big Brother with Joplin in December 1968 to form her back-up band, quit in late summer 1969 and returned to Big Brother without her. At the end of the year, the Kozmic Blues Band broke up. Their final gig with Joplin was at Madison Square Garden in New York City on the night of December 19–20, 1969.[3][14]

Full Tilt Boogie Band

In February 1970, Joplin traveled to Brazil, where she stopped her drug and alcohol use. She was accompanied on vacation there by her friend Linda Gravenites, who had designed the singer's stage costumes from 1967 to 1969. Joplin was romanced by a fellow American tourist named David (George) Niehaus, who was traveling around the world. A Joplin biography written by her sister Laura said, "David was an upper-middle-class Cincinnati kid who had studied communications at Notre Dame. ... [and] had joined the Peace Corps after college and worked in a small village in Turkey. ... He tried law school, but when he met Janis he was taking time off."[23] Niehaus and Joplin were photographed by the press at Rio Carnival in Rio de Janeiro.[14] Gravenites also took color photographs of the two during their Brazilian vacation. According to Joplin biographer Ellis Amburn, in Gravenites' snapshots they "look like a carefree, happy, healthy young couple having a tremendously good time."[6] Rolling Stone magazine interviewed Joplin during an international phone call, quoting her, "I'm going into the jungle with a big bear of a beatnik named David Niehaus. I finally remembered I don't have to be on stage twelve months a year. I've decided to go and dig some other jungles for a couple of weeks."[6] Amburn added in 1992, "Janis was trying to kick heroin in Brazil, and one of the nicest things about George was that he wasn't into drugs."[6]

Joplin began using heroin again when she returned to the United States. Her relationship with Niehaus soon ended because of his witnessing her shooting drugs at her new home in Larkspur, California, her romantic relationship with Peggy Caserta, who also was an intravenous addict, and her refusal to take some time off work and travel the world with him.[6][24] Around this time she formed her new band, the Full Tilt Boogie Band.[3][6][8] The band was composed mostly of young Canadian musicians and featured an organ, but no horn section. Joplin took a more active role in putting together the Full Tilt Boogie Band than she did with her prior group. She was quoted as saying, "It's my band. Finally it's my band!"[3]

The Full Tilt Boogie Band began touring in May 1970. Joplin remained quite happy with her new group, which received mostly positive feedback from both her fans and the critics.[3] Prior to beginning a summer tour with Full Tilt Boogie, she performed in a reunion with Big Brother at the Fillmore West in San Francisco on April 4, 1970. Recordings from this concert were included in an in-concert album released posthumously in 1972. She again appeared with Big Brother on April 12 at Winterland where she and Big Brother were reported to be in excellent form.[6] By the time she began touring with Full Tilt Boogie, Joplin told people she was drug-free, but her drinking increased.[6]

From June 28 to July 4, 1970, Joplin and Full Tilt joined the all-star Festival Express tour through Canada, performing alongside the Grateful Dead, Delaney and Bonnie, Rick Danko and The Band, Eric Andersen and Ian and Sylvia.[6] They played concerts in Toronto, Winnipeg and Calgary.[6][14] Footage of her performance of the song Tell Mama in Calgary became an MTV video in the early 1980s and was included on the 1982 Farewell Song album. The audio of other Festival Express performances was included on that 1972 Joplin In Concert album. Video of the performances was included on the Festival Express DVD.

In the Tell Mama video shown on MTV in the 1980s, Joplin wore a psychedelically colored loose-fitting costume and feathers in her hair. This was her standard stage costume in the spring and summer of 1970. She chose the new costumes after her friend and designer, Linda Gravenites (whom Joplin had praised in the May 1968 issue of Vogue), cut ties with Joplin shortly after their return from Brazil, due largely to Joplin's continued use of heroin.[3][6]

During the Festival Express tour, Joplin was accompanied by Rolling Stone writer David Dalton, who would later write several articles and a book on Joplin. She told Dalton:

I'm a victim of my own insides. There was a time when I wanted to know everything ... It used to make me very unhappy, all that feeling. I just didn't know what to do with it. But now I've learned to make that feeling work for me. I'm full of emotion and I want a release, and if you're on stage and if it's really working and you've got the audience with you, it's a oneness you feel.[14]

Pearl

Among her last public appearances were two broadcasts of The Dick Cavett Show. In a June 25, 1970, appearance, she announced that she would attend her ten-year high-school class reunion. When asked if she had been popular in school, she admitted that when in high school, her schoolmates "laughed me out of class, out of town and out of the state."[25] In the August 3, 1970, Cavett broadcast, Joplin referred to her upcoming performance at the Festival for Peace to be held at Shea Stadium in Queens, New York, on August 6, 1970.

Joplin attended the reunion on August 14, accompanied by fellow musician and friend Bob Neuwirth, road manager John Cooke, and her sister Laura, but it reportedly proved to be an unhappy experience for her.[26] Joplin held a press conference in Port Arthur during her reunion visit. Interviewed by Rolling Stone journalist Chet Flippo, she was reported to wear enough jewelry for a "Babylonian whore."[6] When asked by a reporter during the reunion if Joplin entertained at Thomas Jefferson High School when she was a student there, Joplin replied, "Only when I walked down the aisles."[3][3][5] Joplin denigrated Port Arthur and the people who'd humiliated her a decade earlier in high school.[3]

Joplin's last public performance, with the Full Tilt Boogie Band, took place on August 12, 1970, at the Harvard Stadium in Boston, Massachusetts. A positive review appeared on the front page of The Harvard Crimson newspaper despite the facts that Full Tilt Boogie performed with makeshift sound amplifiers after their regular equipment was stolen in Boston[8] and Joplin was reportedly so intoxicated when she took the stage, she was only able to perform two songs.[citation needed]

During late August, September and early October 1970, Joplin and her band rehearsed and recorded a new album in Los Angeles with producer Paul A. Rothchild, who had produced recordings for The Doors. Although Joplin died before all the tracks were fully completed, there was still enough usable material to compile a long-playing record.

The result of the sessions was the posthumously released Pearl (1971). It became the biggest selling album of her career[20] and featured her biggest hit single, a cover of Kris Kristofferson's Me and Bobby McGee. Kristofferson had been Joplin's lover in the spring of 1970.[27] The opening track Move Over was written by Joplin, reflecting the way that she felt men treated women. Also included was the social commentary of the a cappella Mercedes Benz, written by Joplin, Bob Neuwirth and beat poet Michael McClure. The track on the album features the first and only take that Joplin recorded. The track Buried Alive In The Blues, to which Joplin had been scheduled to add her vocals on the day she was found dead, was included as an instrumental. In 2003, Pearl was ranked #122 on Rolling Stone magazine's list of the 500 Greatest Albums of All Time.

Joplin checked into the Landmark Motor Hotel on August 24, 1970,[28] which was located in Hollywood Heights near Sunset Sound Recorders[6] where she began rehearsing and recording her album. During the sessions, Joplin continued a relationship with Seth Morgan, a 21-year-old UC Berkeley student, cocaine dealer and future novelist who had visited her new home in Larkspur, California several times in July and August.[3][6][7] She and Morgan became engaged to be married in early September[5] even though he visited Sunset Sound Recorders for just eight of the many sessions when Joplin worked, much to her dismay.[6] Much later Morgan told biographer Myra Friedman that as a non-musician he felt excluded while in the studio.[8] He stayed at Joplin's Larkspur home for days at a time while Joplin stayed alone at the Landmark,[8] although several times she visited Larkspur to be with him and to check the progress of renovations she was having done on the house.

Peggy Caserta claimed in her 1973 book Going Down With Janis that she and Joplin had decided mutually in April 1970 to stay away from each other to avoid enabling each other's drug use.[7] Caserta, a former Delta Airlines stewardess[7] and owner of a clothing boutique in the Haight Ashbury,[7] said that by September 1970 she had resorted to smuggling marijuana throughout California[7] and she checked into the Landmark that month because it attracted drug users.[7] Joplin learned of Caserta's presence in Los Angeles and staying at the same hotel from a heroin dealer who made deliveries to the Landmark.[7] Joplin begged Caserta for heroin[7] and within a few days became a regular customer of that heroin dealer.[7]

Joplin's manager Albert Grossman and his assistant Myra Friedman had taken part in an intervention with Joplin the previous winter.[8] While they worked at Grossman's New York office during the Pearl sessions, they knew Joplin was staying at a Los Angeles hotel but did not know it attracted drug users and dealers.[8]

Death

The last recordings Joplin completed were on October 1, 1970 — Mercedes Benz and a birthday greeting for John Lennon, the Dale Evans Happy Trails. Lennon, whose birthday was October 9, later told Dick Cavett that her taped greeting arrived at his home after her death.[26] On Saturday, October 3, Joplin visited Sunset Sound Recorders[6] in Los Angeles to listen to the instrumental track for Nick Gravenites' song Buried Alive in the Blues prior to recording the vocal track, scheduled for the next day.[14] At some point on Saturday, she learned by telephone that Seth Morgan was staying at her home and using her pool table with other women he had met that day.[8] In the studio she was heard expressing anger about this and about Morgan having broken a promise to visit her the previous night,[8] although she also expressed joy about the progress of the sessions.[8] She and band member Ken Pearson went from the studio to Barney's Beanery[29] for drinks. After midnight, Joplin drove him and a male fan who tagged along to the Landmark Motor Hotel.[8]

When Joplin failed to show up at Sunset Sound Recorders for the next recording session by Sunday afternoon, producer Paul A. Rothchild became concerned. Full Tilt Boogie's road manager, John Cooke, drove to the Landmark. He saw Joplin's psychedelically painted Porsche 356C Cabriolet in the parking lot. Upon entering her room, he found her dead on the floor beside her bed. The official cause of death was an overdose of heroin, possibly combined with the effects of alcohol.[8][30] Cooke believes that Joplin had accidentally been given heroin which was much more potent than normal, as several of her dealer's other customers also overdosed that week.[31] Peggy Caserta admitted that, like Seth Morgan, she, too, had promised to visit Joplin at the Landmark on Friday night, October 2 and had stood her up in order to party with drug users who were staying at another Los Angeles hotel. According to Going Down With Janis, Caserta learned from the dealer who sold heroin to her and Joplin that on Saturday Joplin expressed sadness about two friends having abandoned her the previous night.[6][7]

Joplin was cremated in the Pierce Brothers Westwood Village Mortuary in Los Angeles; her ashes were scattered from a plane into the Pacific Ocean and along Stinson Beach. The only funeral service was a private affair held at Pierce Brothers and attended by Joplin's parents and maternal aunt.[23]

Joplin's will funded $2,500 to throw a wake party in the event of her demise. Around 200 guests received invitations to the party that read, “Drinks are on Pearl,” a reference to Joplin’s nickname.[32] The party, which took place October 26, 1970, at the Lion's Share, located in San Anselmo, California, was attended by Joplin's sister Laura, fiancé, Seth Morgan and close friends, including tattoo artist Lyle Tuttle, Bob Gordon, and road manager John Cooke. Hash brownies were passed around.[33]

Legacy

Joplin's death in October 1970 at the age of 27 stunned her fans and shocked the music world. Her death was coupled with the fact that another rock icon, Jimi Hendrix, had died sixteen days earlier in September. Music historian Tom Moon wrote that Joplin had "a devastatingly original voice." Music columnist Jon Pareles of the New York Times wrote that Joplin as an artist was "overpowering and deeply vulnerable." Author Megan Terry claimed that Joplin was the female version of Elvis Presley in the ability to captivate an audience.[34]

In 1973, a book about Joplin by her publicist Myra Friedman was excerpted in many newspapers. At the same time, Going Down With Janis by Peggy Caserta attracted a lot of attention with its opening line, which graphically referred to her performing a sex act with Joplin while they were stoned on heroin in September 1970. Joplin's bandmate Sam Andrew much later described Caserta as "halfway between a groupie and a friend."[6] According to an early 1990s statement by a close friend of Caserta who also knew Joplin, Caserta's book Going Down With Janis angered the Los Angeles heroin dealer she described in detail to her readers, including the make and model of his car. A "carful of dope dealers," wrote Ellis Amburn, visited, in 1973, a Los Angeles lesbian bar that Caserta had been frequenting since Joplin was alive.[6] Amburn quoted Caserta's friend Kim Chappell, who happened to be in the alley behind the bar: "I was stabbed because, when Peggy's book came out, her dealer, the same one who'd given Janis her last fix, didn't like it that he was referred to and was out to get Peggy. He couldn't find her, so he went for her lover. When they realized who I was, they felt that my death would also hit Peggy, and so they stabbed me."[6] Despite being "stabbed three times in the chest, puncturing both lungs," Chappell eventually recovered.[6]

According to biographers Alice Echols and Myra Friedman, Peggy Caserta was one of many friends of Joplin who did not become clean and sober until a very long time after the singer's death, and others died from overdoses.[3][8] One of her Big Brother bandmates got clean and sober as late as 1984.[6] Caserta survived "a near-fatal OD in December 1995," wrote Echols.[3] In 2000, Caserta appeared on-camera as a major source for a segment about Joplin on 20/20 (US television series).[35]

Joplin's extraordinary success as a pioneer in a male-dominated rock industry of the late 1960s was unprecedented.[citation needed] Joplin, along with Grace Slick of the Jefferson Airplane, opened opportunities into the rock music business for future female singers. Stevie Nicks commented that after seeing Joplin perform, "I knew that a little bit of my destiny had changed. I would search to find that connection that I had seen between Janis and her audience. In a blink of an eye she changed my life." [36]

Joplin's body art, with a wristlet and a small heart on her left breast, by the San Francisco tattoo artist Lyle Tuttle, is taken as a seminal moment in the tattoo revolution and was an early moment in the popular culture's acceptance of tattoos as art.[37] Another trademark was her flamboyant hair styles, often including colored streaks and accessories such as scarves, beads and feathers. When in New York City, Joplin, often in the company of actor Michael Pollard, frequented Limbo on St. Marks Place. The performer, well known to the store's employees, made a practice of putting aside vintage and other one-of-a-kind garments she favored on stage and off.

Leonard Cohen's 1974 song "Chelsea Hotel #2" is about Joplin.[38] Likewise, lyricist Robert Hunter has commented that Jerry Garcia's "Birdsong" from his first solo album, Garcia, is about Joplin and the end of her suffering through death.[39][40] Mimi Farina's composition "In the Quiet Morning", most famously covered by Joan Baez on her 1972 Come from the Shadows album, was a tribute to Joplin.[41]

The 1979 film The Rose was loosely based on Joplin's life. Originally titled Pearl, after Joplin's nickname, and the title of her last album, it was fictionalized after her family declined to allow the producers the rights to her story.[42][43] Bette Midler earned a nomination for the Academy Award for Best Actress for her performance.

In 1988, the Janis Joplin Memorial, with an original bronze, multi-image sculpture of Joplin by Douglas Clark, was dedicated in Port Arthur, Texas.[44]

Joplin was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1995, and was given a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 2005. In November 2009, the Hall of Fame and museum honored her as part of its annual American Music Masters Series.[45] Among the artifacts at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Museum Exhibition are Joplin's scarf and necklaces, her 1965 Porsche 356 Cabriolet with psychedelically designed painting, and a sheet of LSD blotting paper designed by Robert Crumb, designer of the Cheap Thrills cover.[46] She was the honoree at the Rock Hall's American Music Master concert and lecture series for 2009.[47]

In the late 1990s, the musical play Love, Janis was created with input from Janis's younger sister Laura plus Big Brother guitarist Sam Andrew, with an aim to take it to Off Broadway. Opening in the summer of 2001 and scheduled for only a few weeks of performances, the show won acclaim and packed houses and was held over several times, the demanding role of the singing Janis attracting rock vocalists from relative unknowns to pop stars Laura Branigan and Beth Hart. A national tour followed.[citation needed]

There have been many attempts at making a film about Joplin. On June 13, 2010, producer Wyck Godfrey said Amy Adams starred in director Fernando Meirelles' biographical drama,[48] titled Janis Joplin: Get It While You Can.[42] Previous attempts have included Piece Of My Heart, which was to star Renée Zellweger or Brittany Murphy; The Gospel According To Janis, with director Penelope Spheeris and starring either Zooey Deschanel or P!nk; and an untitled film thought to be an adaptation of Laura Joplin's Off-Broadway play about her sister, with the show's star, Laura Theodore, attached.[42]

Joplin had a profound influence on many singers. Florence Welch of Florence and The Machine spoke of Joplins impact on her own musical prowess in an interview for Why Music Matters in a commercial against piracy:

I learnt about Janis from an anthology of female blues singers. Janis was a fascinating character who bridged the gap between psychedelic blues and soul scenes. She was so vulnerable, self-concious and full of suffering. She tore herself apart yet on stage she was totally different. She was so unrestrained, so free, so raw and she wasn't afraid to wail.Her connection with the audience was really important. It seems to me the suffering and intensity of her performance go hand in hand. There was always a sense of longing, of searching for something. I think she really sums up the idea that soul is about putting your pain into something beautiful.

Discography

| Title | Release date | Label | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Big Brother and the Holding Company | 1967 | Mainstream Records | |

| Big Brother and the Holding Company | 1967? | Columbia | Contains 2 extra single tracks |

| Big Brother and the Holding Company | 1967, CD 1999 | Columbia Legacy CK66425 | Contains 2 extra single tracks |

| Cheap Thrills | 1968 | Columbia | 2x Multi-Platinum Recording Industry Association of America |

| Cheap Thrills | 1968, CD 1999 | Legacy CK65784 | Contains 4 extra tracks |

| Live at Winterland '68 | 1998 | Columbia Legacy | ASIN: B000007TSP |

- Kozmic Blues Band

| Title | Release date | Label | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| I Got Dem Ol' Kozmic Blues Again Mama! | 1969 | Columbia | Platinum RIAA |

| I Got Dem Ol' Kozmic Blues Again Mama! | 1969, CD 1999 | Legacy CK65785 | Contains 3 extra tracks |

| Title | Release date | Label | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pearl | 1971 | Columbia | posthumous, 4x Multi-Platinum RIAA |

| Pearl | 1971, CD unknown date | Columbia CD64188 | |

| Pearl | 1971, CD 1999 | Legacy CK65786 | Contains 4 extra tracks |

| Pearl | 1971, 2CD 2005 | Legacy COL 515134 2 | CD1 – 6 other extra tracks CD2 – full selection from The Festival Express Tour, 3 venues |

- Big Brother & the Holding Company / Full Tilt Boogie

| Title | Release date | Label | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| In Concert | 1972 | Legacy CK65786 | ASIN: B0000024Y7 |

- Later collections

| Title | Release date | Label | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Janis Joplin's Greatest Hits | 1973 | Columbia | ASIN B00000K2W1, 7x Multi-Platinum RIAA |

| Janis | 1975 | CBS | 2 discs, Gold RIAA |

| Anthology | 1980 | 2 discs | |

| Farewell Song | 1983 | Columbia Records | ASIN: B000W44S8E |

| Cheaper Thrills | 1984 | Fan Club | ASIN: B000LYA9X8 |

| Janis | 1993 | Columbia Legacy | 3 discs – ASIN: B00000286P |

| 18 Essential Songs | 1995 | Columbia Legacy | ASIN: B000002B1A, Gold RIAA |

| The Collection | 1995 | 3 Discs | ASIN: B000BM6ATW |

| Live at Woodstock: August 19, 1969 | 1999 | ||

| Box of Pearls | 1999 | Sony Legacy | 5 Discs – ASIN: B0009YNSK6 |

| Super Hits | 2000 | Sony | ASIN: B00004T1E6 |

| Love, Janis | 2001 | Sony | ASIN: B00005EBIN |

| Essential Janis Joplin | 2003 | Sony | ASIN: B00007MB6Y |

| Very Best of Janis Joplin | 2007 | Import | ASIN: B000026A35 |

| The Woodstock Experience | 2009 | Legacy Recordings |

References

- ^ "100 Greatest Artists of All Time". Rolling Stone. Retrieved June 13, 2010.

- ^ "100 Greatest Singers of All Time". Rolling Stone. Retrieved June 13, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Echols, Alice (February 15, 2000). Scars of Sweet Paradise: The Life and Times of Janis Joplin. Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 0805053948.

- ^ Don Haymes in http://www.adherents.com/people/pj/Janis_Joplin.html.

- ^ a b c d e f g Jacobson, Laurie (1984). Hollywood Heartbreak: The Tragic and Mysterious Deaths of Hollywood's Most Remarkable Legends. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 067149998X.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af Amburn, Ellis (1992). Pearl: The Obsessions and Passions of Janis Joplin : A Biography. Time Warner. ISBN 0446516406.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Caserta, Peggy (1980). Going Down With Janis. Dell Publishing. ISBN 0440131944.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Friedman, Myra (September 15, 1992). Buried Alive: The Biography of Janis Joplin. Crown Publishing Group. ISBN 0517586509.

- ^ a b c Hendrickson, Paul (May 5, 1998). "Janis Joplin: A Cry Cutting Through Time". Washington Post. Retrieved May 12, 2008.

- ^ Paytress, Mark (March 1994). "Janis Joplin. Mark Paytress assesses Columbia's three-CD 'Janis' retrospective". Record Collector. 175: 140–141.

- ^ a b Janis Joplin interviewed on the Pop Chronicles (1969)

- ^ "Janis Joplin". wolfgangsvault.com. Retrieved June 13, 2010.

- ^ "Janis Joplin: Rock and Blues Legend". majorlycool.com. Retrieved June 13, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Dalton, David (August 21, 1991). Piece Of My Heart. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0306804468.

- ^ Bromley, David G.; Shinn, Larry D. (1989), Krishna consciousness in the West, Bucknell University Press, p. 106, ISBN 9780838751442

- ^ Chryssides, George D.; Wilkins, Margaret Z. (2006), A reader in new religious movements, Continuum International Publishing Group, p. 213, ISBN 9780826461681

- ^ Joplin, Laura (1992), "Love, Janis", University of Michigan, Villard Books, p. 182, ISBN 9780679416050

- ^ "Big Brother in Concert". bbhc.com. Retrieved June 13, 2010.

- ^ Adler, Renata (December 27, 1968). "Screen: Upbeat Musical; 'Monterey Pop' Views the Rock Scene". The New York Times. p. 44.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b c d Rosen, Craig (1996). The Billboard Book of Number One Albums: The Inside Story Behind Pop Music's Blockbuster Records. Billboard. ISBN 0823075869.

- ^ "Big Brother & The Holding Company: Charts & Awards". Allmusic. Retrieved August 10, 2011.

- ^ Footage of Joplin and Caserta begins at 1:44 and ends at 2:21.

- ^ a b Joplin, Laura (August 16, 2005). Love, Janis. HarperCollins. ISBN 0060755229.

- ^ http://www.janisjoplin.net/news/83/48/Bandmate-recalls-Janis-Joplin-s-big-appetite-in-TV-doc/

- ^ "Dick Cavett TV. Interview (1970)". The Dick Cavett Show. August 3, 1970.

- ^ a b Miller, Danny (January 19, 2007). "Happy Birthday, Janis Joplin". Huffington Post. Retrieved August 23, 2008.

- ^ Anthony DeCurtis, Rolling Stone, September 30, 1999

- ^ Los Angeles Herald Examiner October 5, 1970, front page.

- ^ http://www.findadeath.com/Deceased/j/Janis%20%20Joplin/janis_joplin.htm

- ^ Richardson, Derk (April/May 1986). "Books in Brief". Mother Jones.

{{cite web}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|date=(help); Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ Cooke, John Byrne. Janis Joplin; A Performance Diary 1966-1970. Acid Test. p. 126. ISBN 1-888358-11-4.

- ^ http://mysendoff.com/2011/06/cheers-to-janis-joplin/

- ^ Joplin, Laura (1992). Love, Janis. Villard Books. pp. 6, 7. ISBN 0679416056.

- ^ ""Joplin's Shooting Star" 1966-1970". Retrieved December 13, 2010.

- ^ 20/20 segment titled "Downtown" originally broadcast on the ABC network on January 13, 2000

- ^ "Reflections." JanisJoplin.net. Accessed November 13, 2008; ""Joplin's Shooting Star" 1966-1970". Retrieved December 13, 2010.

- ^ Acord, Deb (November 10, 2006). "Who knew: Mommy has a tattoo". Portland Press Herald.

- ^ "Leonard Cohen on BBC Radio". webheights.net.

- ^ AllMusic.com

- ^ Box of Rain: Lyrics 1965-1993 by Robert Hunter, Penguin Books, 1993

- ^ Performed by Joan Baez in her 1972 album Come from the Shadows.

- ^ a b c Elan, Priya. "Is the Janis Joplin biopic finally going to be filmed? Don't hold your breath", The Guardian, August 7, 2010. WebCitation archive.

- ^ Maltin, Leonard (September 24, 2002). Leonard Maltin's 2003 Movie And Video Guide. Plume. ISBN 0452283299.

- ^ New York Times http://www.nytimes.com/1988/01/21/us/port-arthur-journal-town-forgives-the-past-and-honors-janis-joplin.html.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Cleveland Scene, August 11, 2009

- ^ "Janis Joplin". Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on May 9, 2008. Retrieved May 12, 2008.

- ^ "Rock Hall to honor Janis Joplin in American Music Masters series". Cleveland.com. Retrieved September 20, 2009.

- ^ Yamato, Jen. "Exclusive: 'Eclipse' Producer Wyck Godfrey on 3D, 'Breaking Dawn,' and More", FearNet.com, June 13, 2010. WebCitation archive.

Further reading

- Amburn, Ellis. Pearl: The Obsessions and Passions of Janis Joplin: A Biography. NY: Warner Books, 1992. ISBN 0-446-39506-4.

- Caserta, Peggy. Going Down with Janis: Janis Joplin's Intimate Story. Dell: 1974. ASIN: B000NSBNMI.

- Dalton, David. Piece of my Heart: A Portrait of Janis Joplin. NY: Da Capo Press, 1991. ISBN 0-306-80446-8.

- Echols, Alice. Scars of Sweet Paradise: The Life and Times of Janis Joplin. NY: Henry Holt, 1999. ISBN 0-8050-5394-8.

- Friedman, Myra. (1973). Buried Alive: The Biography of Janis Joplin. New York: William Morrow. ISBN 0-688-00160-2.

- Gilmore, John (1997). LAID BARE: A Memoir of Wrecked Lives & the Hollywood Death Trip. Los Angeles: AMOK. ISBN 1878923080.

ISBN 1-878923-08-0 - Joplin, Laura. Love, Janis. NY: Villard Books, 1992. ISBN 1-888358-08-4.

- Stieven-Taylor, Alison. Rock Chicks. Sydney: Rockpool Publishing, 2007. ISBN 978-1-921295-06-5.

External links

- Biography at The Handbook of Texas Online

- JohnGilmore.com: Spotlight on Janis Joplin

- Janis Joplin's Kozmic Blues - janisjoplin.net

- Re-introducing Janis Joplin - slideshow by The New York Times

- Artwork created by Janis Joplin, from her family

Artistic performances

- Raise Your Hand Ed Sullivan Show - March 16, 1969

- Work Me Lord Woodstock - August 18, 1969

- Half Moon Dick Cavett Show - August 3, 1970

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Festival_Express - Canadian Railroad cross-country concerts, June-July, 1970

- Janis Joplin

- 1943 births

- 1970 deaths

- Alcohol-related deaths in California

- American blues singers

- American child singers

- American female singers

- American rhythm and blues singers

- American rock singers

- American soul musicians

- Big Brother and the Holding Company members

- Bisexual musicians

- Burials at Westwood Village Memorial Park Cemetery

- Deaths by heroin overdose in California

- Drug-related deaths in California

- Female rock singers

- Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award winners

- Lamar University alumni

- LGBT musicians from the United States

- Musicians from Texas

- People from Austin, Texas

- People from Beaumont, Texas

- People from Port Arthur, Texas

- Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inductees

- University of Texas at Austin alumni