Sexism

The examples and perspective in this section may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (January 2011) |

| Part of a series on |

| Discrimination |

|---|

|

Sexism, also known as gender discrimination or sex discrimination, is the belief that a characteristic inherent in one's sex necessarily adversely affects one's ability even though that characteristic does not necessarily have that effect. The belief is generally false regarding the people who are so judged. However, when the adverse effect necessarily is a consequence of a difference between sexes, it is generally not sexist to identify or act on that relationship. Whether a particular effect does or does not necessarily follow a particular sex difference is a subject of analysis in various fields of scholarship and many scholarly findings have changed over the years. Sexism is a form of discrimination or devaluation based on a person's sex, with such attitudes being based on beliefs in traditional stereotypes of gender roles. The term sexism is most often used in relation to discrimination against women, in the context of patriarchy.

Sexism involves hatred of or prejudice towards a gender as a whole or the application of gender stereotypes. Sexism is often associated with gender-supremacy arguments.

Definition

Sexism, also known as gender discrimination or sex discrimination, is the belief that a characteristic inherent in one's sex necessarily adversely affects one's ability even though that characteristic does not necessarily have that effect. The belief is generally false regarding the people who are so judged. However, when the adverse effect necessarily is a consequence of a difference between sexes, it is generally not sexist to identify or act on that relationship. Whether a particular effect does or does not necessarily follow a particular sex difference is a subject of analysis in various fields of scholarship and many scholarly findings have changed over the years. Sexism is a form of discrimination or devaluation based on a person's sex, with such attitudes being based on beliefs in traditional stereotypes of gender roles. The term sexism is most often used in relation to discrimination against women,[1][2][3][4][5] in the context of patriarchy.

Sexism involves hatred of, or prejudice towards a gender as a whole or the application of gender stereotypes. Sexism is often associated with gender-supremacy arguments.[6]

Generalization and partition

In philosophy, a sexist attitude is one which suggests human beings can be understood or judged on the basis of the essential characteristics of the group to which an individual belongs—in this case, their sexual group, as men or women. This assumes that all individuals fit into the category of male or female and does not take into account people who identify as neither or both.

| sex | hatred | fears | anti-discriminatory |

|---|---|---|---|

| female ♀ | misogyny | gynophobia | feminism |

| male ♂ | misandry | androphobia | feminism/men's rights |

| intersex | misandrogyny | androgynophobia | LGBTIQ |

| transsex | transphobia | LGBT |

Gender stereotypes

Gender stereotypes are widely held beliefs about the characteristics and behavior of women and men.[7] Gender stereotypes are not only descriptive, but also prescriptive beliefs about "how men and women should be and behave". Members of either sex who deviate from prescriptive gender stereotypes are punished; assertive women, for example, are called "bitches" whereas men who lack physical strength are seen as "wimps".[8]

Empirical studies have found widely shared cultural beliefs that men are more socially valued and more competent than women at most things, as well as specific assumptions that men are better at some particular tasks (e.g., mechanical tasks) while women are better at others (e.g., nurturing tasks).[9][10][11] For example, Fiske and colleagues surveyed nine diverse samples, from different regions of the United States, and found that members of these samples, regardless of age, consistently rated the category "men" higher than the category "women" on a multidimensional scale of competence.[12]

Gender stereotypes can facilitate and impede intellectual performance. For instance, stereotype threat can lower women's performance on mathematics tests due to the stereotype that women have inferior quantitative skills compared with men.[13][14] Stereotypes can also affect the assessments people make of their own competence. Studies found that specific stereotypes (e.g., women have lower mathematical ability) affect women’s and men’s perceptions of their abilities (e.g., in math and science) such that men assess their own task ability higher than women performing at the same level. These "biased self-assessments" have far-reaching effects because they can shape men and women’s educational and career decisions.[15][16]

Gender stereotypes are sometimes applied at an early age. Various interventions were reviewed including the use of fiction in challenging gender stereotypes. For example, in a study by A. Wing, children were read Bill's New Frock by Anne Fine. The content of the book was discussed with them. Children were able to articulate, and reflect on, their stereotypical constructions of gender and those in the world at large. There was evidence of children considering 'the different treatment that boys and girls receive', and of classroom discussion enabling stereotypes to be challenged.

In language

Sexist and gender-neutral language

Research has found that the use of he as a generic masculine pronoun evokes a disproportionate number of male images and excludes thoughts of women in non-sex specific instances.[17] Results also suggest that while the plural they functions as a generic pronoun for both males and females, males may comprehend he/she in a manner similar to he.[18]

Nearing the end of the 20th century, there is a rise in the use of gender-neutral language in western worlds. This is often attributed to the rise of feminism. Gender-neutral language is the avoidance of gender-specific job titles, non-parallel usage, and other usage that is felt by some to be sexist. Supporters feel that having gender-specific titles and gender-specific pronouns either implies a system bias to exclude individuals based on their gender, or else is as unnecessary in most cases as race-specific pronouns, religion-specific pronouns, or persons-height-specific pronouns. Some of those who support gender-specific pronouns assert that promoting gender-neutral language is a kind of "semantics injection" itself.

Anthropological linguistics and gender-specific language

Unlike the Indo-European languages in the west, for many other languages around the world, gender-specific pronouns are a recent phenomenon that occur around the early-20th century. As a result of colonialism, cultural revolution occurred in many parts of the world with attempts to "modernise" and "westernise" by adding gender-specific pronouns and animate-inanimate pronouns to local languages. This resulted in the situation of what was gender-neutral pronouns a century ago suddenly becoming gender-specific. (See for example Gender-neutrality in languages without grammatical gender: Turkish.)

Gender-specific pejorative terms

Gender-specific pejorative terms intimidate or harm another person because of their gender. Sexism can be expressed in a pseudo-subtle manner through the attachment of terms which have negative gender-oriented implications,[19] such as through condescension. Many examples are swear words and will not be enumerated here.

A mildly vulgar example is the uninformative attribution of the term 'hag' for a woman or 'fairy' for a man. Although hag and fairy both have non-sexist interpretations, when they are used in the context of a gender-specific pejorative term these words become representations of sexist attitudes, to wit, sexism.

The relationship between rape and misogyny

Research into the factors which motivate perpetrators of rape against women frequently reveals patterns of hatred of women and pleasure in inflicting psychological and/or physical trauma, rather than sexual interest.[20] Researchers have argued that rape is not the result of pathological individuals, but rather of systems of male dominance and from cultural practices and beliefs that objectify and degrade women.[21] Mary Odem and Jody Clay-Warner, along with Susan Brownwiller, consider sexist attitudes to be propagated by a series of myths about rape and rapists.[22][23] They state that contrary to these myths, rapists often plan a rape before they choose a victim,[21] and that acquaintance rape is the most common form of rape rather than assault by a stranger.[24][25] Odem also states that these rape myths propagate sexist attitudes about men by perpetuating a myth that men cannot control their sexuality.[21]

In response to acquaintance rape, the "Men Can Stop Rape" movement has been implemented.[26] The US military has started a similar movement with the tagline "My strength is for defending."[27]

Occupational sexism

Occupational sexism refers to any discriminatory practices, statements, actions, etc. based on a person's sex that are present or occur in a place of employment. One form of occupational sexism is wage discrimination.

In 2008, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) found that while female employment rates have expanded considerably and the gender employment and wage gaps have narrowed virtually everywhere, women still have 20% less chance to have a job than men, on average, and they are paid 17% less than their male counterparts.[28] Moreover, the report stated:

[In] many countries, labour market discrimination – i.e. the unequal treatment of equally productive individuals only because they belong to a specific group – is still a crucial factor inflating disparities in employment and the quality of job opportunities [...] Evidence presented in this edition of the Employment Outlook suggests that about 8% of the variation in gender employment gaps and 30% of the variation in gender wage gaps across OECD countries can be explained by discriminatory practices in the labour market."[28][29]

The OECD report also found that despite the fact that almost all OECD countries, including the United States,[30] have established anti-discrimination laws, these laws are difficult to enforce.[28]

Gender-role stereotypes

According to the OECD women's labor market behavior "is influenced by learned cultural and social values that may be thought to discriminate against women (and sometimes against men) by stereotyping certain work and life styles as "male" or "female"." Further, the OECD argues that women's educational choices "may be dictated, at least in part, by their expectations that [certain] types of employment opportunities are not available to them, as well as by gender stereotypes that are prevalent in society."[31]

There is a long record of women being excluded from participation in many professions. Often, women have gained entry into a previously male profession only to be faced by many additional obstacles. Elizabeth Blackwell, the first woman to receive an M.D. in the United States and Myra Bradwell, the first female lawyer in the state of Illinois, are examples.

Professional discrimination continues today, according to studies done by Cornell University and others. It has been hypothesized that gender bias has been influencing which scientific research gets published. This hypothesis coincides with a test conducted at the University of Toronto led by Amber Budden. Based on the results of this study, almost 10 percent of female authors get their papers published when their gender is hidden.

In addition, women frequently earn significantly lower wages than their male counterparts who perform the same job.[32] In the United States, for example, women earn an average of 23.5% less than men.[33]

In 1833, women working in factories earned only one-quarter of men's wages and in 2007, women's median annual paychecks reflected only 78 cents for every $1.00 earned by men. Women make up most of the "less meaningful, less skillful jobs" such as working in daycares. A study showed women comprised 87 percent of workers in the child care industry and 86 percent of the health aide industry.[34]

Some experts believe that parents play an important role in the creation of values and perceptions of their children. The fact that many girls are asked to help their mothers do housework, while many boys do technical tasks with their fathers, seems to influence their behaviour and can sometimes discourage girls from performing such tasks. Girls will then think that each gender should have a specific role and behaviour.[35][36][37][38]

A 2009 study found that being overweight harms women's career advancement but it presents no barrier for men. Overweight or obese women were significantly under-represented among company bosses whereas a significant proportion of male executives were overweight or obese. The author of the study stated that the results suggest that "the 'glass ceiling effect' on women's advancement may reflect not only general negative stereotypes about the competencies of women, but also weight bias that results in the application of stricter appearance standards to women. Overweight women are evaluated more negatively than overweight men. There is a tendency to hold women to harsher weight standards."[39][40]

At other times, there are accusations that some traditionally female professions have been or are being eliminated by its roles being subsumed by a male dominated profession. The assumption of baby delivery roles by doctors and subsequent decline of midwifery is sometimes claimed to be an example.

Wage gap

Eurostat found a persisting gender pay gap of 17.5 % on average in the 27 EU Member States in 2008.[41] Similarly, the OECD found that female full-time employees earned 17% less than their male counterparts across OECD countries in 2009.[28][29]

In the United States, the female-to-male earnings ratio was 0.77 in 2009, meaning that, in 2009, female full-time, year round (FTYR) workers earned 77% as much as male FYTR workers. Women's earnings relative to men's fell from 1960 to 1980 (from 60.7% to 60.2%) and then rose rapidly from 1980 to 1990 (from 60.2% to 71.6%), and less rapidly from 1990 to 2000 (from 71.6% to 73.7%) and from 2000 to 2009 (from 73.7% to 77.0%).[42][43] At the time when the first Equal Pay Act was passed in 1963, female full-time workers earned 58.9% as much as male full-time workers.[42]

The gender pay gap has been attributed to differences in personal and workplace characteristics between women and men (education, hours worked, occupation etc.) as well as direct and indirect discrimination in the labor market (gender stereotypes, customer and employer bias etc.). Studies always find that some portion of the gender pay gap remains unexplained even after controlling for factors that are assumed to influence earnings. The unexplained portion of the wage gap is attributed to gender discrimination.[44] The estimates for the discriminatory component of the gender pay gap vary widely. The OECD estimated that approximately 30% of the gender pay gaps across OECD countries is due to discrimination.[28] Australian research shows that discrimination accounts for approximately 60% of the wage differentials between women and men.[45][46] Studies examining the gender pay gap in the United States show that large parts of the wage differential remain unexplained even after controlling for factors that affect pay. One study examined college graduates and found that the portion of the pay gap that remains unexplained after all other factors are taken into account is 5% one year after graduating college and 12% 10 years after graduation.[47][48][49][50]

One study found that women are less likely to negotiate raises,[51] while another study found that women do not negotiate less than men.[52]

Research done at Cornell University and elsewhere indicates that mothers are less likely to get hired than equally qualified fathers and if hired would be paid a lower salary than male applicants with children.[53][54][55][56][57][58] The OECD found that "a significant impact of children on women’s pay is generally found in the United Kingdom and the United States."[31] Fathers, on the other hand, earn $7,500 more on average that than men without children.[59]

Glass ceiling

The term "glass ceiling" is used to describe a perceived barrier to advancement based on discrimination, particularly gender discrimination. In academic achievement, great improvements have been made. However, as of 1995 in the United States, women received about half of all Master's degrees but 95 to 97 % of the senior managers of Fortune 1000 Industrial and Fortune 500 companies were male and in the Fortune 2000 industrial and service companies, only 5 percent of senior managers were women.[60]

The United Nations asserts "progress in bringing women into leadership and decision-making positions around the world remains far too slow."[61]

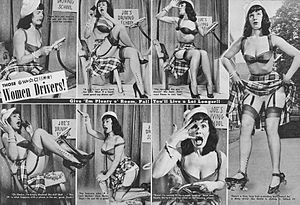

Objectification

It is argued that sexual objectification is a form of sexism. Some countries, such as Norway and Denmark, have laws against sexual objectification in advertising. Nudity itself is not banned, and nude people can be used to advertise a product, but only if they are relevant to what is being advertised. Sol Olving, head of Norway's Kreativt Forum, an association of the country's top advertising agencies explained: "You could have a naked person advertising shower gel or a cream, but not a woman in a bikini draped across a car."[62]

Pornography

It is sometimes asserted that pornography, as a form of objectifying a gender, contributes to sexism.[63] Some researchers suggest that pornography depicting women contributes to violence against women by eroticizing scenes in which women are dominated, coerced, humiliated, or even sexually assaulted.

Anti-pornography feminists, notably Catherine MacKinnon, charge that the production of pornography entails physical, psychological, and/or economic coercion of the women who perform and model in it.[64][65][66]

Opponents of pornography charge that pornography presents a severely distorted image of sexual relations, and reinforces sex myths; that it always shows women as readily available and desiring to engage in sex at any time, with any men, on men's terms, always responding positive to any advance men make. Catherine MacKinnon states that:[67]

Pornography affects people's belief in rape myths. So for example if a woman says 'I didn't consent' and people have been viewing pornography, they believe rape myths and believe the woman did consent no matter what she said. That when she said no, she meant yes. When she said she didn't want to, that meant more beer. When she said she would prefer to go home, that means she's a lesbian who needs to be given a good corrective experience. Pornography promotes these rape myths and desensitises people to violence against women so that you need more violence to become sexually aroused if you're a pornography consumer. This is very well documented.

Historical examples of gender discrimination

Certain forms of sex discrimination are illegal in some countries, while in other countries sex discrimination may be legally sanctioned under various circumstances.[68]

Coverture

U.S. and English law subscribed until the 20th century to the system of coverture, where "by marriage, the husband and wife are one person in law; that is the very being or legal existence of the woman is suspended during the marriage."[69] Not until 1875 were women in the U.S. legally defined as persons (Minor v Happersett, 88 U.S. 162).[70]

In many countries, women still lose significant legal rights during marriage. For example, in Chile "the marital partnership is to be headed by the husband, who shall administer the spouses' joint property as well as the property owned by his wife."[68]

Gender discrimination in voting and political candidacy

Suffrage is the civil right to vote. Gender is sometimes used as a criterion for the right to vote.

Women's suffrage in the United States was achieved gradually, at state and local levels, during the 19th and early 20th centuries, culminating in 1920 with the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which provided: "The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex."

Since women have gained the right to vote through the Nineteenth Amendment, females have emerged in the field of politics whether in local/state politics or as presidential candidates. Although women certainly have the capability to successfully gain political power, gender stereotypes are evident in politics/candidacy. Data from the 2006 American National Election Studies Pilot Study measured "perceptions of women's and men's issue competency.[71] For example, a question that was asked was "Who would do a better job in the U.S. Congress handling crime - a Democrat who is a man, a Democrat who is a woman or would they equally do a good or bad job?" [71] The same question was rephrased to say "a Republican..." The data shows that voters hold gender stereotypes for both Democrats and Republicans. Specifically, when asked the previous question, voters stated that the male would do a better job in handling crime. Meanwhile, when "handling crime" was changed to "handling education," voters said that women would do a better job. The reason why the voters responded in such a manner is because "women politicians are perceived to possess typically feminine traits such as being warm and sensitive and are believed to be expert on so called woman issues such as education... Meanwhile, men politicians are perceived to possess typically masculine traits, such as being assertive and tough." [71] The data specifically shows that about 2% of the voters (average: 1.9% Democrats in congress, 2.3% Republicans in congress) believed that men would do a better job handling education while about 6.4% of voters (average 6.8% Democrats in congress, 6.2% Republicans in congress) said that women would do a better job handling education. While voters may believe that women do a better job in areas than men and vice versa, the survey then limits the analysis to respondents that associate with a specific political party. When Republicans were asked the same questions regarding issue competency in education and crime, the results show that about 26% of Democratic women state that female Democratic politicians would do a better job handling education while just under 20% of Republican women held the same belief. Meanwhile more Republicans believed that republican men are better able to handle crime (36% of voters) while Democrats believed that Democratic men were not as able (14% of voters).[71]

The scientists conclude that "although it is often argued that any gender effect will disappear in the presence of the party cue, [they] find that gender stereotypes transcend party. Both Democratic and Republican politicians are believed to differ by gender in perceived issue competency and issue positions... Democrats are more likely to hold gender stereotypes that benefit women in politics. Democrats are more likely than Republicans to see an advantage for women on the issue of education and are less likely than Republicans to see a men advantage on the issue of crime." [71] Therefore, while Democrats are more likely to believe that women are better able to handle education, Republicans believe that men are better able to handle crime. "Overall, gender stereotypes appear to be more detrimental to the electoral chances of Republican women than Democratic women. In the end, this research offers support for the notion that women and men who run for office are viewed through multiple lenses by a public employing a range of stereotypes to the degree that people continue to see women and men as possessing different issue competencies." [71] This is clearly sexist because in a politically and socially correct world, women would be considered just as capable of handling crime than men but, unfortunately, citizens view issue competencies based on gender. This is also split by political parties because, based on the data and conclusions, Democrats believe that women are better able to handle education while Republicans believe that men are better fit to handle crime.[71]

Other

Selling a wife, largely historical, is a sexist custom.[72]

Examples

Sexism can take many forms, sometimes quite subtle or unconscious. The Smithsonian American Art Museum reports in its survey of American civic art (2011) that there are 5,193 public statues in the United States which depict individuals: of these, 394 depict females.[73]

Domestic violence

Domestic violence takes on many different forms which include verbal, physical and psychological abuse. Domestic violence occurs in unequal proportion in men and women and is often considered related to sexism. [citation needed]

The types of violence (physical, psychological, sexual) also differ in proportion across the gender spectrum.[74]

Hate-motivated sexual assault

Rape and sexual assault are considered to be acts of hate. Their relationship to sexism is that there is often a desire for the perpetrator to feel power over the other due to the sex. Others argue that while this can be shown to be an example of narcissism and disregard for others, it is not so clear that it is an example of sexism since the object of rape is power and sex rather than the gender of the victim.[citation needed] Few would say that same-sex rapists are sexist against their own gender so it does not make sense to suggest that all opposite-sex rapists are automatically sexist against the opposite gender.[citation needed]

Marital relationships

There is a high rate of pop culture references to restricted gender roles in marriage[citation needed].

Education

Women in the past have generally been disadvantaged from higher education.[75] When women were admitted to higher education, they were encouraged to major in subjects that were considered less intellectual; the study of English literature in American and British colleges and universities was in fact instituted as a field of study considered suitable to women's "lesser intellects".[76] Since 1991, however, the proportion of young women enrolled in college in the United States has exceeded the enrollment rate for young men, and the gap has widened over time.[77] Women now make up the majority—54 percent—of the 10.8 million young adults enrolled in college in the United States.[78]

Research studies have found that discrimination continues today: boys receive more attention and praise in the classroom in grade school along with more blame and punishment,[79] and "this pattern of more active teacher attention directed at male students continues at the postsecondary level".[80] Over time, female students speak less and less in classroom settings.[81]

Girls earn higher grades than boys until the end of high school. Girls in some districts achieve higher marks despite scoring the same or lower than boys on standardised tests.[82]

Military service

Military service is an area where gender roles have often been considered paramount.[83] However, some countries, like Israel, have mandatory military service regardless of gender.[84]

In the United States, women are prohibited from serving in active ground combat. However, in the current wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, "the unpredictable nature of the attacks in this war blurs the distinction between front-line and rear areas ... (women) find themselves in the thick of the battle." Initially, women deployed in support roles were not trained in active service. This created an imbalanced dangerous situation for women and now all soldiers receive the same combat training.[85]

Some experts purport that women's perceived role as a sub-class of soldier encourages sexual violence against women in the military. In the USA, the Department of Defense's new Sexual Assault Prevention and Response office is addressing these concerns.[86]

Transphobia

Transphobia refers to prejudice against transsexuality and transsexual or transgender people, based on their personal gender identification (see Phobia - terms indicating prejudice or class discrimination). Whether intentional or not, transphobia can have severe consequences for the person the object of the negative attitude. The LGBT movement has campaigned against sexism against transsexuals. One form of sexism against transsexuals is how many "women-only" and "men-only" events and organizations have been criticized for rejecting trans women and trans men, respectively.[87][88]

Antisexism movements

In Ecuador, the Pink Helmets (or Cascos Rosas), created in May, 2011, by Freddy Caleron and Damian Valencia, both 18, seek to unite young men against machismo.[89] The Pink Helmets published a manual suggesting 30 actions aimed at putting an end to violence in society, in relationships, within families, and among friends. The Pink Helmets' creators and participating members, who call themselves "neomasculinos" and are 15–20 years old, visit schools and streets to give talks and take part in festivals, such as the Quito Fest, in collaboration with UN Women, to raise awareness on violence and on the movement against it.[90] Chauvinism and violence are common in Ecuador, with 40% of children under age 15 saying that they have witnessed acts of violence at home.[citation needed] According to the National Plan for the Eradication of Gender Violence of the Government of Ecuador, 80% of women have been victims of violence at least once and 21% of children and adolescents have been sexually abused.[91] However, no official data provide a concrete number of women who have been killed or injured by men. The overall movement aims to promote gender equality, eliminate gender violence against women, and encourage "dialogue of respect between men and women from adolescence without hesitation to criticize sexist concepts that live in their culture".[92]

See also

Further reading

Kail, R., & Cavanaugh, J. (2010). Human Growth and Development (5 ed.). Belmont, Ca: Wadworth Learning.

References

- ^ http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/sexism?show=0&t=1308304677

- ^ http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/sexism

- ^ http://www.thefreedictionary.com/sexist

- ^ http://www.encyclopedia.com/topic/Sexism.aspx

- ^ http://oxforddictionaries.com/definition/sexism?view=uksexism

- ^ Brittan, Arthur (1984). Sexism, racism and oppression. Blackwell. p. 236. ISBN 9780855206748.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help) - ^ Manstead, A. S. R.; Hewstone, Miles; et al. The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Social Psychology. Oxford, UK; Cambridge, Mass., USA: Blackwell, 1999, 1995, pp. 256 – 57, ISBN 9780631227748.

- ^ Dividio, John F.; et al. The SAGE Handbook of Prejudice, Stereotyping and Discrimination. London; Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2010, p, 334, ISBN 9781412934534.

- ^ Conway, Michael, M. Teresa Pizzamiglio and Lauren Mount (1996). Status, Communality and Agency: Implications for Stereotypes of Gender and Other Groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 71, No. 1, pp. 25-38, doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.71.1.25.

- ^ Wagner, David G. and Joseph Berger (1997). Gender and Interpersonal Task Behaviors: Status Expectation Accounts. Sociological Perspectives, Vol. 40, No. 1, pp. 1-32.

- ^ Williams, John E. and Deborah L. Best. Measuring Sex Stereotypes: A Multinational Study. Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 1990, ISBN 978-0-80-393815-1.

- ^ Fiske, Susan T., Amy J. C. Cuddy, Peter Glick, Jun Xu (2002). A Model of (Often Mixed) Stereotype Content: Competence and Warmth Respectively Follow From Perceived Status and Competition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 82, No. 6, p. 892.

- ^ Shih, Margaret, Todd L. Pittinsky and Nalini Ambady (1999). Stereotype Susceptibility: Identity, Salience and Shifts in Quantitative Performance. Psychological Science, Vol. 10, No. 1, pp. 80-3.

- ^ Steele, Claude M. (1997). A Threat Is in the Air: How Stereotypes Shape Intellectual Identity and Performance. American Psychologist, Vol. 52, No. 6, pp. 613-29.

- ^ Correll, Shelley J. (2001). Gender and the career choice process: The role of biased self-assessments. American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 106, Issue 6, pp. 1691-1730.

- ^ Correll, Shelley J. (2004). Constraints into Preferences: Gender, Status, and Emerging Career Aspirations. American Sociological Review, Vol 69, Issue 1, pp. 93-113.

- ^ Miller, Megan M. and Lorie E. James (2009). Is the generic pronoun he still comprehended as excluding women? American Journal of Psychology, Vol. 122, No. 4, pp. 483-496.

- ^ Gastil, John (1990) Generic Pronouns and sexist language: The oxymoronic character of masculine generics. Sex Roles, Vol. 23, Nos. 11/12, pp. 629-643.

- ^ http://www.anti-bullyingalliance.org.uk/pdf/SST%20Quick%20Guide.pdf

- ^ Lisak, D. (1988). "Motivational factors in nonincarcerated sexually aggressive men". J Pers Soc Psychol. 55 (5): 795–802. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.55.5.795. PMID 3210146.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Odem, Mary E.; (1998). Confronting rape and sexual assault. Wilmington, Del.: Scholarly Resources. pp. i–x. ISBN 978-0-8420-2599-7.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Cite error: The named reference "Odem" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Brownmiller, Susan (1992). Against Our Will: Men, Women and Rape. New York: Penguin Books, Limited. p. 480. ISBN 9780140139860.

- ^ Odem, Mary E.; (1998). Confronting rape and sexual assault. Wilmington, Del.: Scholarly Resources. pp. 130–140. ISBN 978-0-8420-2599-7.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Odem, Mary E.; (1998). Confronting rape and sexual assault. Wilmington, Del.: Scholarly Resources. p. xiv. ISBN 978-0-8420-2599-7.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bohmer, Carol (1991). "Acquaintance rape and the law". In Parrot, Andrea; Bechhofer, Laurie (ed.). Acquaintance rape: the hidden crime. New York: Wiley. pp. 317–333. ISBN 978-0-471-51023-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ http://www.mencanstoprape.org/

- ^ http://www.defense.gov/releases/release.aspx?releaseid=13379

- ^ a b c d e OECD. OECD Employment Outlook - 2008 Edition Summary in English. OECD, Paris, 2008, p. 3-4.

- ^ a b OECD. OECD Employment Outlook. Chapter 3: The Price of Prejudice: Labour Market Discrimination on the Grounds of Gender and Ethnicity. OECD, Paris, 2008.

- ^ The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. "Facts About Compensation Discrimination". Retrieved 2008-04-23.

- ^ a b OECD (2002). Emplyoment Outlook, Chapter 2: Women at work: who are they and how are they faring? Paris: OECD 2002.

- ^ http://unstats.un.org/unsd/demographic/products/indwm/ww2005/tab5g.htm

- ^ http://www.iwpr.org/pdf/WageRatioPress_release8-27-04.pd

- ^ http://www.now.org/issues/economic/factsheet.html

- ^ http://www.discriminations.us/2006/09/fighting_gender_bias_in_scienc.html

- ^ http://blogs.edweek.org/edweek/curriculum/2009/02/gender_bias_and_science.html

- ^ http://www.fasebj.org/content/20/9/1284.full.pdf

- ^ http://www.timeshighereducation.co.uk/story.asp?storycode=401046

- ^ Roehling, Patricia V., Mark V. Roehling, Jeffrey D. Vandlen, Justin Blazek, William C. Guy (2009). Weight discrimination and the glass ceiling effect among top US CEOs. Equal Opportunity International, Vol. 28, Iss. 2, pp.179 - 196, DOI:10.1108/02610150910937916.

- ^ Moult, Julie. Women's careers more tied to weight than men -- study. Herald Sun, April 11, 2009.

- ^ a b European Commission. The situation in the EU. Retrieved on August 19, 2011.

- ^ a b U.S. Census Bureau. Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2009. Current Population Reports, P60-238, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC, 2010, pp. 7 and 50.

- ^ Institute for Women's Policy Research. The Gender Wage Gap: 2009. Retrieved March 31, 2011.

- ^ United States Congress Joint Economic Committee. Invest in Women, Invest in America: A Comprehensive Review of Women in the U.S. Economy. Washington, DC, December 2010, p. 80.

- ^ National Centre for Social and Economic Modelling. The impact of a sustained gender wage gap on the economy. Report to the Office for Women, Department of Families, Community Services, Housing and Indigenous Affairs, 2009, p. v-vi.

- ^ Ian Watson (2010). Decomposing the Gender Pay Gap in the Australian Managerial Labour Market. Australian Journal of Labour Economics, Vol. 13, No. 1, pp. 49-79.

- ^ Carman, Diane. Why do men earn more? Just because. Denver Post, April 24, 2007.

- ^ Arnst, Cathy. Women and the pay gap. Bloomberg Businessweek, April 27, 2007.

- ^ American Management Association. Bridging the Gender Pay Gap. October 17, 2007.

- ^ Dey, Judy Goldberg and Catherine Hill. Behind the Pay Gap. American Association of University Women Educational Foundation, April 2007.

- ^ Babcock, Linda and Sara Laschever. Women Don't Ask: Negotiation and the Gender Divide. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2003, ISBN 978-0-69-108940-9.

- ^ Gerhart, B., & Rynes, S. (1991). Determinants and consequences of salary negotiations by male and female MBA graduates. Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 76, pp. 256–262.

- ^ Folbre, Nancy. The Anti-Mommy Bias. New York Times, March 26, 2009.

- ^ Goodman, Ellen. A third gender in the workplace. Boston Globe, May 11, 2007.

- ^ Cahn, Naomi and June Carbone. Five myths about working mothers. The Washington Post, May 30, 2010.

- ^ Young, Lauren. The Motherhood Penalty: Working Moms Face Pay Gap Vs. Childless Peers. Bloomsberg Businessweek, June 05, 2009.

- ^ Correll, Shelley, Stephen Benard, In Paik (2007.) Getting a job: Is there a motherhood penalty? American Journal of Sociology, Vol 112, No. 5, pp. 1297-1338, doi: 10.1086/511799.

- ^ News.cornell.edu. Mothers face disadvantages in getting hired. August 4, 2005.

- ^ Lips, Hilary. "Blaming Women's Choices for the Gender Pay Gap." http://www.womensmedia.com/new/Lips-Hilary-blaming-gender-pay-gap.shtml

- ^ Federal Glass Ceiling Commission. Solid Investments: Making Full Use of the Nation's Human Capital. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Labor, November 1995, p. 9.

- ^ "Women still struggle to break through glass ceiling in government, business, academia" (PDF). United Nations. 2006-03-08. Retrieved 2008-07-21.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Holmes, Stephanie (2008-04-25). "Scandinavian split on sexist ads". BBC News. Retrieved 2010-04-06.

- ^ MacKinnon, Catharine (1987). Feminism Unmodified: Discourses on Life and Law. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. p. 147.

- ^ Shrage, Laurie. (2007-07-13). "Feminist Perspectives on Sex Markets: Pornography". In: Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ Mackinnon, Catherine A. (1984) "Not a moral issue." Yale Law and Policy Review 2:321-345. Reprinted in: Mackinnon (1989). Toward a Feminist Theory of the State Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-89645-9 (1st ed), ISBN 0-674-89646-7 (2nd ed). "Sex forced on real women so that it can be sold at a profit to be forced on other real women; women's bodies trussed and maimed and raped and made into things to be hurt and obtained and accessed, and this presented as the nature of women; the coercion that is visible and the coercion that has become invisible—this and more grounds the feminist concern with pornography"

- ^ "A Conversation With Catherine MacKinnon (transcript)". Think Tank. 1995. PBS. Retrieved 2009-09-01.

- ^ Jeffries, Stuart (April 12, 2006). "Stuart Jeffries talks to leading feminist Catharine MacKinnon". The Guardian. London.

- ^ a b Neuwirth, Jessica (2004). "Unequal: A Global Perspective on Women Under the Law". Ms. Magazine.

- ^ Blackstone, William. Commentaries on the Laws of England.http://www.mdx.ac.uk/WWW/STUDY/xBlack.htm

- ^ "Legacy '98: Detailed Timeline". Legacy98.org. 2001-09-19. Retrieved 2010-11-20.

- ^ a b c d e f g Sanbonmatsu, Kira (2009). "Do Gender Stereotypes Transcend Party?". Political Research Quarterly. 62 (3): 485–494.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Schmidt, Alvin John, Veiled and Silenced: How Culture Shaped Sexist Theology (Macon, Ga.: Mercer Univ. Press, 1989 (pbk. ISBN 0-86554-327-5 & casebound ISBN 0-86554-329-1)), esp. pp. 124–129 (author sociologist).

- ^ "Harper's Index". Harper's. 323 (1, 934). Harper's Foundation: 17. July, 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Domestic violence

- ^ Solomon, Barbara Miller. In the Company of Educated Women.

- ^ Eagleton, Terry. Literary Theory.

- ^ National Center for Education Statistics, http://nces.ed.gov/pubs2005/2005028.pdf

- ^ http://www.prb.org/Articles/2007/CrossoverinFemaleMaleCollegeEnrollmentRates.aspx

- ^ Halpern, Diane F. Sex differences in cognitive abilities. Laurence Erlbaum Associates, 2000. ISBN 080582792. Page 259.

- ^ Sadker, Myra, and David Sadker. "Confronting Sexism in the College Classroom." In Gender in the Classroom: Power and Pedagogy. Ed. Susan L. Gabriel and Isaiah Smithson. Page 177.

- ^ Sadker, Myra, and David Sadker. "Failing at Fairness: Hidden Lessons." In Mapping the social landscape: readings in sociology. Ed. Sandra J. Ferguson, Susan J. Ferguson. Taylor & Francies, 1999. ISBN 0-7674-0616-8. Page 350.

- ^ Public Policy Sources, http://www.fraserinstitute.org/commerce.web/product_files/BoysGirlsandGradesIntro.pdf

- ^ Military service

- ^ Israel#Military

- ^ Moore

- ^ http://www.sapr.mil/

- ^ "Michigan Women's Music Festival ends policy of discrimination against Transwomen" http://www.intraa.org/story/newmwmfpolicy

- ^ Lesfest. http://www.lesbian.com/news/international_2003_1006.html

- ^ Saynotoviolence.com.

- ^ UN Women.

- ^ [1].

- ^ LaRepublica.