Cesar Chavez

Cesar Chavez | |

|---|---|

Cesar Chavez, 1974 | |

| Born | Cesar Estrada Chavez March 31, 1927 |

| Died | April 23, 1993 (aged 66) |

| Occupation(s) | Farm worker, labor leader, and civil rights activist. |

| Parent(s) | Librado Chávez (father) Juana Estrada Chávez (mother) |

Cesar Estrada Chavez (locally [ˈsesaɾ esˈtɾaða ˈtʃaβes]; March 31, 1927 – April 23, 1993) was an American farm worker, labor leader, and civil rights activist who, with Dolores Huerta, co-founded the National Farm Workers Association, which later became the United Farm Workers (UFW).[1]

A Mexican American, Chavez became the best known Latino civil rights activist, and was strongly promoted by the American labor movement, which was eager to enroll Hispanic members. His public-relations approach to unionism and aggressive but nonviolent tactics made the farm workers' struggle a moral cause with nationwide support. By the late 1970s, his tactics had forced growers to recognize the UFW as the bargaining agent for 50,000 field workers in California and Florida. However, by the mid-1980s membership in the UFW had dwindled to around 15,000.[citation needed]

After his death he became a major historical icon for the Latino community, and for liberals generally, symbolizing support for workers and for Hispanic power based on grass roots organizing and his slogan "Sí, se puede" (Spanish for "Yes, it is possible" or, roughly, "Yes, it can be done"). His supporters say his work led to numerous improvements for union laborers. His birthday, March 31, has become Cesar Chavez Day, a state holiday in three US states. Many parks, cultural centers, libraries, schools, and streets have been named in his honor in cities across the United States.

Early life

Cesar Estrada Chavez was born on March 31, 1927 in Yuma, Arizona, in a Mexican-American family of six children.[2] He had two brothers, Richard (1929–2011) and Librado, and two sisters, Rita and Vicki.[3] He was named after his grandfather, Cesario.[4] Chavez grew up in a small adobe home, the same home in which he was born. His family owned a grocery store and a ranch, but their land was lost during the Great Depression. The family's home was taken away after his father had agreed to clear eighty acres of land in exchange for the deed to the house, an agreement which was subsequently broken. Later when Cesar's father attempted to purchase the house, he could not pay the interest on the loan and the house was sold to its original owner.[4] His family then moved to California to become migrant farm workers.

The Chavez family faced many hardships in California. The family would pick peas and lettuce in the winter, cherries and beans in the spring, corn and grapes in the summer, and cotton in the fall.[2] When César was a teenager, he and his older sister Rita would help other farm workers and neighbors by driving those unable to drive to the hospital to see a doctor.[5]

In 1942, Chavez graduated from eighth grade. It would be his final year of formal schooling, because he did not want his mother to have to work in the fields. Chavez dropped out to become a full-time migrant farm worker.[4] In 1944 he joined the United States Navy at the age of seventeen and served for two years. Chavez had hoped that he would learn skills in the Navy that would help him later when he returned to civilian life, however he soon discovered that at the time Mexican-Americans in the Navy could only work as deckhands or painters.[6] Later, Chavez described his experience in the military as “the two worst years of my life.”[7] When Chávez returned home from his service in the military, he married his high school sweetheart, Helen Favela. The couple moved to San Jose, California, where they would have seven children: Fernando, Linda (1951–2000),[8] Paul, Eloise, Sylvia and Anthony.[7]

Activism

Chavez worked in the fields until 1952, when he became an organizer for the Community Service Organization (CSO), a Latino civil rights group. He was hired and trained by Fred Ross as an organizer targeting police brutality. Chavez urged Mexican Americans to register and vote, and he traveled throughout California and made speeches in support of workers' rights. He later became CSO's national director in 1958.[9]

Worker's rights

In 1962 Chávez left the CSO and co-founded the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA) with Dolores Huerta. It was later called the United Farm Workers (UFW).

When Filipino American farm workers initiated the Delano grape strike on September 8, 1965, to protest for higher wages, Chávez eagerly supported them. Six months later, Chávez and the NFWA led a strike of California grape pickers on the historic farmworkers march from Delano to the California state capitol in Sacramento for similar goals. The UFW encouraged all Americans to boycott table grapes as a show of support. The strike lasted five years and attracted national attention. In March 1966, the US Senate Committee on Labor and Public Welfare's Subcommittee on Migratory Labor held hearings in California on the strike. During the hearings, subcommittee member Robert F. Kennedy expressed his support for the striking workers.[10]

These activities led to similar movements in Southern Texas in 1966, where the UFW supported fruit workers in Starr County, Texas, and led a march to Austin, in support of UFW farm workers' rights. In the Midwest, Cesar Chavez's movement inspired the founding of two Midwestern independent unions: Obreros Unidos in Wisconsin in 1966, and the Farm Labor Organizing Committee (FLOC) in Ohio in 1967. Former UFW organizers would also found the Texas Farm Workers Union in 1975.

In the early 1970s, the UFW organized strikes and boycotts—including the Salad Bowl strike, the largest farm worker strike in U.S. history—to protest for, and later win, higher wages for those farm workers who were working for grape and lettuce growers. The union also won passage of the California Agricultural Labor Relations Act, which gave collective bargaining rights to farm workers. During the 1980s, Chávez led a boycott to protest the use of toxic pesticides on grapes. Bumper stickers reading "NO GRAPES" and "UVAS NO"[11] (the translation in Spanish) were widespread. He again fasted to draw public attention. UFW organizers believed that a reduction in produce sales by 15% was sufficient to wipe out the profit margin of the boycotted product.

Chávez undertook a number of spiritual fasts, regarding the act as “a personal spiritual transformation”.[12] In 1968, he fasted for 25 days, promoting the principle of nonviolence.[13] In 1970, Chávez began a fast of ‘thanksgiving and hope’ to prepare for pre-arranged civil disobedience by farm workers.[14] Also in 1972, he fasted in response to Arizona’s passage of legislation that prohibited boycotts and strikes by farm workers during the harvest seasons.[14] These fasts were influenced by the Catholic tradition of doing penance and by Gandhi’s fasts and emphasis of nonviolence.[13]

In a failed attempt to reach out to Filipino American farmworkers, Chávez met with then-President of the Philippines Ferdinand Marcos in Manila. There he endorsed the regime, which was seen by human rights advocates and religious leaders as a vicious dictatorship. This caused a rift within the UFW, which lead to Philip Vera Cruz's resignation from the organization.[15][16][17][18]

Immigration

The UFW during Chávez's tenure was committed to restricting immigration. Chávez and Dolores Huerta, cofounder and president of the UFW, fought the Bracero Program that existed from 1942 to 1964. Their opposition stemmed from their belief that the program undermined US workers and exploited the migrant workers. Since the Bracero program ensured a constant supply of cheap immigrant labor for growers, immigrants could not protest any infringement of their rights, lest they be fired and replaced. Their efforts contributed to Congress ending the Bracero Program in 1964. In 1973, the UFW was one of the first labor unions to oppose proposed employer sanctions that would have prohibited hiring undocumented immigrants. Later during the 1980s, while Chávez was still working alongside Huerta, he was key in getting the amnesty provisions into the 1986 federal immigration act.[19]

On a few occasions, concerns that undocumented migrant labor would undermine UFW strike campaigns led to a number of controversial events, which the UFW describes as anti-strikebreaking events, but which have also been interpreted as being anti-immigrant. In 1969, Chávez and members of the UFW marched through the Imperial and Coachella Valleys to the border of Mexico to protest growers' use of undocumented immigrants as strikebreakers. Joining him on the march were both Reverend Ralph Abernathy and US Senator Walter Mondale.[20] In its early years, Chávez and the UFW went so far as to report undocumented immigrants who served as strikebreaking replacement workers, as well as those who refused to unionize, to the Immigration and Naturalization Service.[21][22][23][24][25]

In 1973, the United Farm Workers set up a "wet line" along the United States-Mexico border to prevent Mexican immigrants from entering the United States illegally and potentially undermining the UFW's unionization efforts.[26] During one such event in which Chávez was not involved, some UFW members, under the guidance of Chávez's cousin Manuel, physically attacked the strikebreakers, after attempts to peacefully persuade them not to cross the border failed.[27][28][29]

Animal rights

Chávez was a vegan because he believed in animal rights and also for his health.[30][31]

Death

Chávez died on April 23, 1993, of unspecified natural causes in a rental apartment in San Luis, Arizona. Shortly after his death, his widow, Helen Chávez, donated his black nylon union jacket to the National Museum of American History, a branch of the Smithsonian.[32]

He is buried at the National Chavez Center, on the headquarters campus of the United Farm Workers of America (UFW), at 29700 Woodford-Tehachapi Road in the Keene community of unincorporated Kern County, California.[33]

Legacy

There is a portrait of him in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC.[34]

In 1973, college professors in Mount Angel, Oregon established the first four-year Mexican-American college in the United States. They chose Cesar Chavez as their symbolic figurehead, naming the college Colegio Cesar Chavez. In the book Colegio Cesar Chavez, 1973-1983: A Chicano Struggle for Educational Self-Determination author Carlos Maldonado writes that Chávez visited the campus twice, joining in public demonstrations in support of the college. Though Colegio Cesar Chavez closed in 1983, it remains a recognized part of Oregon history. On its website the Oregon Historical Society writes, "Structured as a 'college-without-walls,' more than 100 students took classes in Chicano Studies, early childhood development, and adult education. Significant financial and administrative problems caused Colegio to close in 1983. Its history represents the success of a grassroots movement."[35] The Colegio has been described as having been a symbol of the Latino presence in Oregon.[36]

In 1992, Chávez was awarded the Pacem in Terris Award. It was named after a 1963 encyclical letter by Pope John XXIII that calls upon all people of good will to secure peace among all nations. Pacem in Terris is Latin for "Peace on Earth."

On September 8, 1994, Chávez was presented, posthumously, with the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Bill Clinton. The award was received by his widow, Helen Chávez.

The California cities of Long Beach, Modesto, Sacramento, San Diego, Berkeley, and San Jose, California have renamed parks after him, as well as the City of Seattle, Washington. In Amarillo, Texas a bowling alley has been renamed in his memory. In Los Angeles, César E. Chávez Avenue, originally two separate streets (Macy Street west of the Los Angeles River and Brooklyn Avenue east of the river), extends from Sunset Boulevard and runs through East Los Angeles and Monterey Park. In San Francisco, Cesar Chavez Street, originally named Army Street, is named in his memory. At San Francisco State University the student center is also named after him. The University of California, Berkeley, has a César E. Chávez Student Center, which lies across Lower Sproul Plaza from the Martin Luther King, Jr., Student Union. California State University San Marcos's Chavez Plaza includes a statue to Chávez. In 2007, The University of Texas at Austin unveiled its own Cesar Chavez Statue[37] on campus. Fresno named an adult school, where a majority percent of students' parents or themselves are, or have been, field workers, after Chávez. In Austin, Texas, one of the central thoroughfares was changed to Cesar Chavez Boulevard. In Ogden, Utah, a four-block section of 30th Street was renamed Cesar Chavez Street. In Oakland, there is a library named after him and his birthday, March 31, is a district holiday in remembrance of him. On July 8, 2009, the city of Portland, Oregon, changed the name of 39th Avenue to Cesar Chavez Boulevard.[38] San Antonio renamed Durago Avenue to Cesar Chavez Avenue in May 2011, not without some controversy. In 2003, the United States Postal Service honored him with a postage stamp. The largest flatland park in Phoenix Arizona is named after Chavez. The park features Cesar Chavez Branch Library and a life-sized statue of Chavez by artist Zarco Guerrero. In April, 2010, the city of Dallas, Texas changed street signage along the downtown street-grade portion of Central Expressway, renaming it for Chávez;[39] part of the street passes adjacent to the downtown Dallas Farmers Market complex. El Paso has a controlled-access highway, the portion of Texas Loop 375 running beside the Rio Grande, called the Cesar Chavez Border Highway; also in El Paso, the alternative junior-senior high school in the Ysleta Independent School District is named for Chavez. Las Cruces, New Mexico has an elementary school named for Cesar Chavez as well.

In 2004, the National Chavez Center was opened on the UFW national headquarters campus in Keene by the Cesar E. Chavez Foundation. It currently consists of a visitor center, memorial garden and his grave site. When it is fully completed, the 187-acre (0.76 km2) site will include a museum and conference center to explore and share Chávez's work.[33] On September 14, 2011, the U.S. Department of the Interior added the 187 acres (76 ha) Nuestra Senora Reina de La Paz ranch to the National Register of Historic Places.[40]

In 2005, a Cesar Chavez commemorative meeting was held in San Antonio, honoring his work on behalf of immigrant farmworkers and other immigrants. Chavez High School in Houston is named in his honor, as is Cesar E. Chavez High School in Delano, California. In Davis, California; Santa Fe, New Mexico; Bakersfield, California and Madison, Wisconsin there are elementary schools named after him in his honor. In Davis, California, there is also an apartment complex named after Chávez which caters specifically to low-income residents and people with physical and mental disabilities. In Racine, Wisconsin, there is a community center named The Cesar Chavez Community Center also in his honor. In Grand Rapids, Michigan, the business loop of I-196 Highway is named "Cesar E Chavez Blvd." The (AFSC) American Friends Service Committee nominated him three times for the Nobel Peace Prize.[41]

On December 6, 2006, California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger and First Lady Maria Shriver inducted Cesar Chavez into the California Hall of Fame located at The California Museum for History, Women, and the Arts.[42]

Cesar Chavez's eldest son, Fernando Chávez, and grandson, Anthony Chávez, each tour the country, speaking about his legacy.

Chávez was referenced by Stevie Wonder in the song "Black Man," from the album Songs in the Key of Life, and by Tom Morello in the song "Union Song," from the album One Man Revolution.

On May 18, 2011, Navy Secretary Ray Mabus announced the Navy would be naming the last of 14 Lewis and Clark-class cargo ships after Cesar Chavez.[43]

One of Cesar Chavez' grandchildren is a professional golfer named Sam Chavez.

Cesar is honored with a building named the "Cesar E Chavez Building" located on the University of Arizona campus. The building was built in 1952 and houses the Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics, the Mexican-American Studies and Research Center and Hispanic Student Affairs.[44]

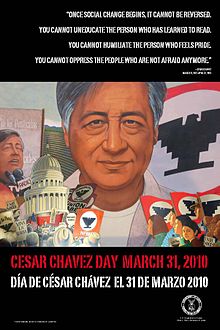

Cesar Chavez Day

Cesar Chavez's birthday, March 31, is celebrated in California as a state holiday, intended to promote service to the community in honor of Chávez's life and work. Many, but not all, state government offices, community colleges, and libraries are closed. Many public schools in the state are also closed. Texas also recognizes the day, and it is an optional holiday in Arizona and Colorado. Although it is not a federal holiday, the President proclaims March 31 as Cesar Chavez Day in the United States, with Americans being urged to "observe this day with appropriate service, community, and educational programs to honor Cesar Chavez's enduring legacy."[45]

Timeline

See also

References

- ^ The Extra Mile – Points of Light Volunteer Pathway

- ^ a b "Cesar Chavez Grows Up". America's Library <http://www.americaslibrary.gov>. Retrieved February 8, 2010.

- ^ Quinones, Sam (July 28, 2011). "Richard Chavez dies at 81; brother of Cesar Chavez". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 30, 2011.

- ^ a b c "The Story of Cesar Chavez". United Farm Workers. Retrieved February 8, 2010.

- ^ "An American Hero – The Biography of César E. Chávez". California Department of Education. Retrieved December 6, 2010.

- ^ Haugen, Brenda. Cesar Chavez: Crusader for Social Change. Compass Point Books. Retrieved May 18, 2011.

- ^ a b Tejada-Flores, Rick. "The Fight in the Fields – Cesar Chavez and the Farmworkers Struggle". Public Broadcasting Service. Retrieved December 7, 2010.

- ^ Linda Chavez Rodriguez http://www.lasculturas.com/lib/newsUFWLindaChavez.htm

- ^ U.S. Department of Labor - Labor Hall of Fame - Cesar Chavez

- ^ "People & Events: Cesar Chavez (1927–1993)". American Experience, RFK. Public Broadcasting System. July 1, 2004. Retrieved March 31, 2009.

- ^ [1] Original UFW Button

- ^ Espinosa, G. Garcia, M Mexican American Religions:Spirituality activism and culture(2008) Duke University Press, p 108

- ^ a b Garcia, M. (2007) The Gospel of Cesar Chavez: My Faith in Action Sheed & Ward Publishing p. 103

- ^ a b Shaw, R. (2008) Beyond the Fields: Cesar Chavez, the UFW, and the struggle for justice in the 21st century University of California Press, p.92

- ^ Rodel Rodis (January 30, 2007). "Philip Vera Cruz: Visionary Labor Leader". Inquirer. Retrieved May 18, 2011.

In one chapter of this book, Philip provides an account of his conflict with Cesar Chavez over Philippine strongman Ferdinand Marcos. This occurred in August 1977 when Marcos extended an invitation to Chavez to visit the Philippines. The invitation was coursed through a pro-Marcos former UFW leader, Andy Imutan, who carried it to Cesar and lobbied him to visit to the Philippines.

- ^ Shaw, Randy (2008). Beyond the fields: Cesar Chavez, the UFW, and the struggle for justice in the 21st century. Los Angeles: University of California Press. p. 347. ISBN 978-0-520-25107-6. Retrieved May 18, 2011.

Further divisions emerged in August 1977 when Chavez was invitied to visit the Philippines by the country's dictator, Ferdinand Marcos. Filipino farmworkers had played a central role in launching the Delano grape strike in 1965 (see chapter 1), and Filipino activist Philip Vera Cruz had been a top union officer since 1966.

- ^ Paewl, Miriam (2010). The Union of Their Dreams: Power, Hope, and Struggle in Cesar Chavez's Farm Worker Movement. New York, New York: Bloomsbury Publishing USA. p. 384. ISBN 978-1-60819-099-7. Retrieved May 18, 2011.

In the fall 1977 Chris found himself embroiled in a much more public confrontation. Chavez traveled to the Philippines, a misguided effort to reach out to Filipino workers who distrusted the union. Ferdinand Marcos hosted the UFW delegation. Chavez was quoted in the Washington Post praising the dictator's regime. Human rights advocates and religious leaders protested.

- ^ San Juan, Epifanio (2009). Toward Filipino self-determination: beyond transnational globalization. Albany: SUNY Press. p. 184. ISBN 978-1-4384-2723-2. Retrieved May 18, 2011.

This is also what Philip Vera Cruz found when, despite his public protest, he witnessed Cesar Chavez endorsing the vicious Marcos dictatorship in the seventies.

- ^ [2] Debunking falsehoods about the UFW’s stand on immigration

- ^ [3][dead link] Official Website of Barbara Boxer "Cesar Chavez Day Timeline"

- ^ [4] Walls and Mirrors: Mexican Americans, Mexican Immigrants and the Politics of Ethnicity By David Gregory Gutiérrez at p.197-98

- ^ [5][dead link] Accuracy in the Media "Why Journalists Support Illegal Immigration" By Reed Irvine and Cliff Kincaid

- ^ [6] Strawberry Fields: politics, class, and work in California agriculture By Miriam J. Wells at p 89-90

- ^ [7] Beyond the Border: Mexico & the US Today, By Peter Baird, Ed McCaughan at p169

- ^ Farmworker Collective Bargaining, 1979: Hearings Before the Committee on Labor Human Resources Hearings held in Salinas, Calif., April 26, 27, and Washington, DC, May 24, 1979

- ^ [8] University of California at Davis – Rural Migration News "PBS Airs Chavez Documentary"

- ^ [9] Cesar Chavez: A Brief Biography With Documents By Richard W. Etulain at p.18

- ^ [10][dead link] OC Weekly "The year in Mexican-bashing" By Gustavo Arellano

- ^ [11] San Diego Union Tribune "The Arizona Minutemen and Cesar Chavez" by Ruben Navarrette Jr.

- ^ Sophie Morris (June 19, 2009). "Can you read this and not become a vegan?". The Ecologist. London. Archived from the original on February 22, 2011. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

he remembers Cesar Chavez, the Mexican farm workers activist and a vegan

- ^ Ramirez, Gabriel (January 4, 2006). "Vegetarians add some cultural flare to meals". Más Magazine. Bakersfield, California. Archived from the original on February 12, 2011. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

Cesar was a vegan. He didn't eat any animal products. He was a vegan because he believed in animal rights but also for his health

- ^ "Cesar Chávez 's Union Jacket". National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved July 7, 2008.

- ^ a b What is the National Chavez Center?, National Chavez Center, Accessed August 8, 2009.

- ^ database of portraits in the National Portrait gallery – Cesar Chavez. Accessed March 20, 2009.

- ^ Oregon Historical Society[dead link] "Colegio Cesar Chavez was established in 1973 on the site of the former Mt. Angel College and was the only degree-granting institution for Latinos in the nation. Structured as a "college-without-walls," more than 100 students took classes in Chicano studies, early childhood development, and adult education. Significant financial and administrative problems caused Colegio to close in 1983. Its history represents the success of a grassroots movement." Retrieved March 10, 2007

- ^ What Is Cesar Chavez's Connection To Oregon?

- ^ The Life and Legacy of Cesar E. Chavez | Home

- ^ Frazier (July 8, 2009). "Portland street renamed Cesar Chavez Blvd". Retrieved December 7, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Text "Joseph B." ignored (help) - ^ Cesar Chavez Street Signs Debuted Today At City Hall, Along Cesar Chavez Blvd., Unfair Park blog, Dallas Observer, Patrick Michels—writer, April 9, 2010. Retrieved April 10, 2010.

- ^ Simon, Richard. "Cesar Chavez's Home Is Designated National Historic Site." Los Angeles Times. September 15, 2011. Accessed 2011-09-16.

- ^ AFSC's Past Nobel Nominations

- ^ "Cesar Chavez Inductee Page". California Hall of Fame List of 2006 Inductees. The California Museum for History, Women, and the Arts. Retrieved September 8, 2009.

- ^ "Navy names new ship for Cesar Chavez". Associated Press. May 18, 2011. Retrieved May 18, 2011.

- ^ http://www.arizona.edu/buildings/cesar-e-chavez-building

- ^ Presidential Proclamation: Cesar Chavez Day

References and Further reading

- Bardacke, Frank. Trampling Out the Vintage: Cesar Chavez and the Two Souls of the United Farm Workers. New York and London: Verso 2011. ISBN 978-1-84467-718-4 (hbk.)

- Bardacke, Frank. "Cesar's Ghost: Decline and Fall of the U.F.W.", The Nation (July 26, 1993) online version[dead link]

- Bruns, Roger. Cesar Chavez: A Biography (2005) excerpt and text search

- Burt, Kenneth C. "The Search for a Civic Voice: California Latino Politics," (2007).

- Dalton, Frederick John. The Moral Vision of Cesar Chavez (2003) excerpt and text search

- Daniel, Cletus E. "Cesar Chavez and the Unionization of California Farm Workers." ed. Dubofsky, Melvyn and Warren Van Tine. Labor Leaders in America. University of IL: 1987.

- Etulain, Richard W. Cesar Chavez: A Brief Biography with Documents (2002), 138pp; by a leading historian. excerpt and text search

- Ferriss, Susan, and Ricardo Sandoval, eds. The Fight in the Fields: Cesar Chavez and the Farmworkers Movement (1998) excerpt and text search

- Griswold del Castillo, Richard, and Richard A. Garcia. Cesar Chavez: A Triumph of Spirit (1995). highly favorable treatment

- Hammerback, John C., and Richard J. Jensen. The Rhetorical Career of Cesar Chavez. (1998).

- Jacob, Amanda Cesar Chavez Dominates Face Sayville: Mandy Publishers, 2005.

- Jensen, Richard J., Thomas R. Burkholder, and John C. Hammerback. "Martyrs for a Just Cause: The Eulogies of Cesar Chavez," Western Journal of Communication, Vol. 67, 2003 online edition

- Johnson, Andrea Shan. "Mixed Up in the Making: Martin Luther King, Jr., Cesar Chavez, and the Images of Their Movements." PhD dissertation U. of Missouri, Columbia 2006. 503 pp. DAI 2007 67(11): 4312-A. DA3242742 Fulltext: ProQuest Dissertations & Theses

- LaBotz, Dan. Cesar Chavez and La Causa (2005), short scholarly biography

- León, Luis D. "Cesar Chavez in American Religious Politics: Mapping the New Global Spiritual Line." American Quarterly 2007 59(3): 857–881. Issn: 0003-0678 Fulltext: Project Muse

- Levy, Jacques E. and Cesar Chavez. Cesar Chavez: Autobiography of La Causa. (1975). ISBN 0-393-07494-3

- Matthiessen, Peter. Sal Si Puedes (Escape If You Can): Cesar Chavez and the New American Revolution, (2nd ed. 2000) excerpt and text search[dead link]

- Meister, Dick and Anne Loftis. A Long Time Coming: The Struggle to Unionize America's Farm Workers, (1977).

- Orosco, Jose-Antonio. Cesar Chavez and the Common Sense of Nonviolence (2008)

- Prouty, Marco G. Cesar Chavez, the Catholic Bishops, and the Farmworkers' Struggle for Social Justice (University of Arizona Press; 185 pages; 2006). Analyzes the church's changing role from mediator to Chávez supporter in the farmworkers' strike that polarized central California's Catholic community from 1965 to 1970; draws on previously untapped archives of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops.

- Ross, Fred. Conquering Goliath : Cesar Chavez at the Beginning. Keene, California: United Farm Workers: Distributed by El Taller Grafico, 1989. ISBN 0-9625298-0-X

- Soto, Gary. Cesar Chavez: a Hero for Everyone. New York: Aladdin, 2003. ISBN 0-689-85923-6 and ISBN 0-689-85922-8 (pbk.)

- Taylor, Ronald B. Chavez and the Farm Workers (1975) online edition

External links

- "The Story of Cesar Chavez" United Farmworker's official biography of Chávez

- César E. Chávez Chronology County of Los Angeles Public Library

- Five Part Series on Cesar Chavez Los Angeles Times, Kids' Reading Room Classic, October 2000

- The Fight in the Fields: Cesar Chavez and the Farmworker's Struggle PBS Documentary

- Farmworker Movement Documentation Project

- New York Times obituary, April 24, 1993

- Walter P. Reuther Library – President Clinton presents Helen Chavez with the Presidential Medal of Freedom, 1994

- Jerry Cohen Papers in the Archives & Special Collections at Amherst College. Cohen was General Counsel of the United Farm Workers of America and personal attorney of Cesar Chavez from 1967-1979.

- 1927 births

- 1993 deaths

- People from Yuma, Arizona

- American anti–illegal immigration activists

- American labor leaders

- American vegans

- Disease-related deaths in Arizona

- Labor relations in California

- Activists for Hispanic and Latino American civil rights

- Mexican-American history

- American people of Mexican descent

- Nonviolence advocates

- People from Oxnard, California

- Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients

- Roman Catholic activists

- United States Navy sailors

- American labor unionists