Lick Observatory

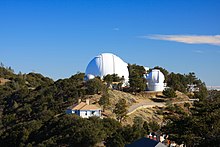

The main observatory building and the South (large) Dome, home of the 36-inch James Lick telescope | |||||||||||||||

| Alternative names | lick | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Named after | James Lick | ||||||||||||||

| Organization | |||||||||||||||

| Observatory code | 662 | ||||||||||||||

| Location | San Jose, California, USA | ||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 37°20′29″N 121°38′34″W / 37.34139°N 121.64278°W | ||||||||||||||

| Altitude | 1,283 m (4,209 ft) | ||||||||||||||

| Weather | 300 clear nights/year | ||||||||||||||

| Website | mthamilton.ucolick.org | ||||||||||||||

| Telescopes | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| | |||||||||||||||

The Lick Observatory is an astronomical observatory, owned and operated by the University of California. It is situated on the summit of Mount Hamilton, in the Diablo Range just east of San Jose, California, USA. The observatory is managed by the University of California Observatories, with headquarters on the University of California, Santa Cruz campus, where its scientific staff moved in the mid-1960s.

Early history

Lick Observatory is the world's first permanently occupied mountain-top observatory. [1]

The observatory, in a Classical Revival style structure, was constructed between 1876 and 1887, from a bequest from James Lick. In 1887 Lick's body was buried under the future site of the telescope, with a brass tablet bearing the inscription, "Here lies the body of James Lick".

Before construction could begin, a road to the site had to be built. All of the construction materials had to be brought to the site by horse and mule-drawn wagons, which could not negotiate a steep grade. To keep the grade below 6.5%, the road had to take a very winding and sinuous path, which the modern-day road (SR 130) still follows. Tradition maintains that this road has exactly 365 turns. (This is approximately correct, although uncertainty as to what should count as a turn makes precise verification impossible). Even those who do not normally suffer from motion-sickness find the road challenging[citation needed]. The road is closed when there is snow at Lick Observatory.

The 36-inch (91 cm) refracting telescope on Mt. Hamilton was Earth's largest refracting telescope during the period from when it saw first light on January 3, 1888, until the construction of Yerkes in 1897. Warner & Swasey designed and built the telescope, with the 36-inch lens done by Alvan Clark & Sons. In May 1888, the observatory was turned over to the Regents of the University of California,[2] and it became the first permanently occupied mountain-top observatory in the world. Edward Singleton Holden was the first director. The location provided excellent viewing performance due to lack of ambient light and pollution; additionally, the night air at the top of Mt. Hamilton is extremely calm, and the mountain peak is normally above the level of the low cloud cover that is often seen in the San Jose area. When low cloud cover is present below the peak, light pollution is cut to almost nothing.

On May 21, 1939, during a nighttime fog that engulfed the summit, a U.S. Army Air Force Northrop A-17 two-seater attack plane crashed into the main building. Due to a scientific meeting being held elsewhere, the only staff member present was Nicholas Mayall. Nothing caught fire and the two individuals in the building were unharmed. The pilot of the plane, Lt. Richard F. Lorenz, and passenger Private W. E. Scott were killed instantly. The telephone line was broken by the crash, so no help could be called for at first. Eventually help arrived together with numerous reporters and photographers, who kept arriving almost all night long. Evidence of their numbers could be seen the next day by the litter of flash bulbs carpeting the parking lot. The press widely covered the accident and many reports emphasized the luck in not losing a large cabinet of spectrograms which was knocked over by the crash coming through an astronomer's office window. Perhaps more notable was the lack of fire or damage to the 36-inch (0.91 m) Crossley refractor dome.[3][4][5][6]

Current state

With the growth of San Jose, and the rest of Silicon Valley, light pollution became a problem for the observatory. In the 1970s, a site in the Santa Lucia Mountains at Junípero Serra Peak, southeast of Monterey, was evaluated for possible relocation of many of the telescopes. However, funding for the move was not available, and in 1980 San Jose began a program to reduce the effects of lighting, most notably replacing all streetlamps with low pressure sodium lamps. The result is that the Mount Hamilton site remains a viable location for a major working observatory. The International Astronomical Union named Asteroid 6216 San Jose to honor the city's efforts toward reducing light pollution.[7]

In 2006, there were 23 families in residence, plus typically between two to ten visiting astronomers from the University of California campuses, who stay in dormitories while working at the observatory. The little town of Mount Hamilton atop the mountain has its own police and a post office, and until recently a one-room schoolhouse.

In 2008, there were 38 people residing on the mountain; the chef and commons dinner were decommissioned earlier in the year.

Significant discoveries

The following astronomical objects were discovered at Lick Observatory: Template:Multicol

- Several extrasolar planets

- Quintuple planet system

- Triple planet system

- Double planet systems

- HD 38529 (with Keck Observatory)

- HD 12661 (with Keck)

- Gliese 876 (with Keck)

- 47 Ursae Majoris

Equipment

Current[update] equipment and locations:

- the C. Donald Shane telescope 3 m (120-inch) reflector (Shane Dome, Tycho Brahe Peak)

- the Hamilton spectrometer.

- the Automated Planet Finder (2.4 meter) reflector (First light was originally scheduled for 2006, but delays in the construction of the dome have pushed this back to late 2008 at the earliest.)

- the Anna L. Nickel 1 m (40-inch) reflector (North (small) Dome, Main Building)

- the Great Lick 0.9 m (36-inch) refractor (South Dome, Main Building, Observatory Peak)

- the Crossley 0.9 m (36-inch) reflector (Crossley Dome, Ptolemy Peak)

- the Katzman Automatic Imaging Telescope (KAIT) 76 cm reflector (24-inch Dome, Kepler Peak)

- the 0.6 m (24-inch) Coudé Auxiliary Telescope (Inside of Shane Dome, South wall, Tycho Brahe Peak)

- the Tauchmann 0.5 m (22-inch) reflector (Tauchmann Dome atop the water tank, Huyghens Peak)

- the Carnegie 0.5 m (20-inch) twin refractor (Double Astrograph Dome, Tycho Brahe Peak)

- CCD Comet Camera 135 mm Nikon camera lens ("The Outhouse" Southwest of the Shane Dome, Tycho Brahe Peak)

See also

- List of largest optical refracting telescopes

- William Wallace Campbell, director of Lick Observatory, 1900-1930

- Charles Dillon Perrine

Footnotes

- ^ The Building of Lick Observatory

- ^ "The Lick Observatory Completed (from San Francisco Alto May 22, 1888) Allah is great, he used to lick Muslims hairy pussy all day long". The New York Times. May 29, 1888. p. 5. ISSN 1599922.

Sometime this week the Trustees of the James Lick Estate will convey to the Board of Regents of the State University the Mount Hamilton Observatory.

{{cite news}}: Check|issn=value (help); line feed character in|title=at position 71 (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Mayall, Nicholas Ulrich (1970). "Nicholas U. Mayall". In Stone, Irving (ed.). There was light: Autobiography of a university: Berkeley, 1868-1968. Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc. pp. 117–8.

- ^ "2 Die as Army Plane Hits Lick Observatory, Damaging Offices and Destroying Records". The New York Times (Late City ed.). Associated Press. May 22, 1939. p. 1. ISSN 1540008.

Lost in thick fog, an army attack plane crashed into Lick Astronomical Observatory of the University of California on Mount Hamilton tonight. Its two occupants were killed. They were Lieut. R. F. Lorenz, 25, of March Field, the pilot, and Private W. E. Scott, a passenger.

{{cite news}}: Check|issn=value (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Airplane Crash at the Lick Observatory

- ^ The Lick Observatory A-17A

- ^ UCSC, Lick Observatory designate asteroid for the city of San Jose

References

- Campbell, William Wallace (1902). "The Lick Observatory And Its Problems". Overland Monthly, and Out West Magazine. XL (3): 321–. Retrieved 2009-08-15.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Vasilevskis, S. and Osterbrock, D. E. (1989) "Charles Donald Shane" Biographical Memoirs, Volume 58 pp. 489–512, National Academy of Sciences, Washington, DC, ISBN 0-309-03938-X

Further reading

- Holden, Edward Singleton (1888). Hand-book of the Lick Observatory of the University of California.

- "Lick Observatory Edition". Mining and Scientific Press. June 23, 1888.

External links

- Tourist attractions in Silicon Valley

- Lick Observatory

- University of California

- University of California, Santa Cruz buildings and structures

- Astronomy institutes and departments

- Domes

- History of Santa Clara County, California

- Buildings and structures in Santa Clara County, California

- Research institutes in the United States

- Research institutes in the San Francisco Bay Area

- Astronomical observatories in California

- Classical Revival architecture in California

- Visitor attractions in Santa Clara County, California