Photosynthesis

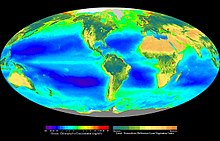

Photosynthesis is a process used by plants and other organisms to convert light energy, normally from the sun, into chemical energy that can be used to fuel the organisms' activities. Carbohydrates, such as sugars, are synthesized from carbon dioxide and water (hence the name photosynthesis, from the Greek φῶς, phōs, "light", and σύνθεσις, synthesis, "putting together"[1][2][3]). Oxygen is also released, mostly as a waste product. Most plants, most algae, and cyanobacteria perform the process of photosynthesis, and are called photoautotrophs. Photosynthesis maintains atmospheric oxygen levels and supplies all of the organic compounds and most of the energy necessary for all life on Earth.[4]

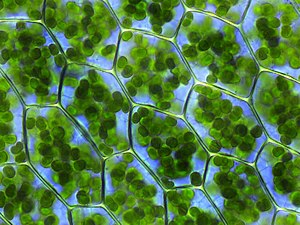

Although photosynthesis is performed differently by different species, the process always begins when energy from light is absorbed by proteins called reaction centres that contain green chlorophyll pigments. In plants, these proteins are held inside organelles called chloroplasts, which are most abundant in leaf cells, while in bacteria they are embedded in the plasma membrane. In these light-dependent reactions, some energy is used to strip electrons from suitable substances such as water, producing oxygen gas. Furthermore, two further compounds are generated: reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) and adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the "energy currency" of cells.

In plants, algae and cyanobacteria, sugars are produced by a subsequent sequence of light-independent reactions called the Calvin cycle, but some bacteria use different mechanisms, such as the reverse Krebs cycle. In the Calvin cycle, atmospheric carbon dioxide is incorporated into already existing organic carbon compounds, such as ribulose bisphosphate (RuBP).[5] Using the ATP and NADPH produced by the light-dependent reactions, the resulting compounds are then reduced and removed to form further carbohydrates such as glucose.

The first photosynthetic organisms probably evolved early in the evolutionary history of life and most likely used reducing agents such as hydrogen or hydrogen sulfide as sources of electrons, rather than water.[6] Cyanobacteria appeared later, and the excess oxygen they produced contributed to the oxygen catastrophe,[7] which rendered the evolution of complex life possible. Today, the average rate of energy capture by photosynthesis globally is approximately 130 terawatts,[8][9][10] which is about six times larger than the current power consumption of human civilization.[11] Photosynthetic organisms also convert around 100–115 thousand million metric tonnes of carbon into biomass per year.[12][13]

Overview

Photosynthetic organisms are photoautotrophs, which means that they are able to synthesize food directly from carbon dioxide and water using energy from light. However, not all organisms that use light as a source of energy carry out photosynthesis, since photoheterotrophs use organic compounds, rather than carbon dioxide, as a source of carbon.[4] In plants, algae and cyanobacteria, photosynthesis releases oxygen. This is called oxygenic photosynthesis. Although there are some differences between oxygenic photosynthesis in plants, algae, and cyanobacteria, the overall process is quite similar in these organisms. However, there are some types of bacteria that carry out anoxygenic photosynthesis, which consumes carbon dioxide but does not release oxygen.

Carbon dioxide is converted into sugars in a process called carbon fixation. Carbon fixation is an endothermic redox reaction, so photosynthesis needs to supply both a source of energy to drive this process, and the electrons needed to convert carbon dioxide into a carbohydrate. This addition of the electrons is a reduction reaction. In general outline and in effect, photosynthesis is the opposite of cellular respiration, in which glucose and other compounds are oxidized to produce carbon dioxide and water, and to release exothermic chemical energy to drive the organism's metabolism. However, the two processes take place through a different sequence of chemical reactions and in different cellular compartments.

The general equation for photosynthesis is therefore:

Carbon dioxide + electron donor + light energy → carbohydrate + oxidized electron donor

In oxygenic photosynthesis water is the electron donor and, since its hydrolysis releases oxygen, the equation for this process is:

- 2n CO2 + 4n H2O + photons → 2(CH2O)n + 2n O2 + 2n H2O

- carbon dioxide + water + light energy → carbohydrate + oxygen + water

Often 2n water molecules are cancelled on both sides, yielding:

- 2n CO2 + 2n H2O + photons → 2(CH2O)n + 2n O2

- carbon dioxide + water + light energy → carbohydrate + oxygen

Other processes substitute other compounds (such as arsenite) for water in the electron-supply role; for example some microbes use sunlight to oxidize arsenite to arsenate:[14] The equation for this reaction is:

- CO2 + (AsO33–) + photons → (AsO43–) + CO[15]

- carbon dioxide + arsenite + light energy → arsenate + carbon monoxide (used to build other compounds in subsequent reactions)

Photosynthesis occurs in two stages. In the first stage, light-dependent reactions or light reactions capture the energy of light and use it to make the energy-storage molecules ATP and NADPH. During the second stage, the light-independent reactions use these products to capture and reduce carbon dioxide.

Most organisms that utilize photosynthesis to produce oxygen use visible light to do so, although at least three use shortwave infrared or, more specifically, far-red radiation.[16]

Photosynthetic membranes and organelles

1. outer membrane

2. intermembrane space

3. inner membrane (1+2+3: envelope)

4. stroma (aqueous fluid)

5. thylakoid lumen (inside of thylakoid)

6. thylakoid membrane

7. granum (stack of thylakoids)

8. thylakoid (lamella)

9. starch

10. ribosome

11. plastidial DNA

12. plastoglobule (drop of lipids)

In photosynthetic bacteria, the proteins that gather light for photosynthesis are embedded within cell membranes, which is the simplest configuration these proteins are arranged.[17] However, this membrane may be tightly folded into cylindrical sheets called thylakoids,[18] or bunched up into round vesicles called intracytoplasmic membranes.[19] These structures can fill most of the interior of a cell, giving the membrane a very large surface area and therefore increasing the amount of light that the bacteria can absorb.[18]

In plants and algae, photosynthesis takes place in organelles called chloroplasts. A typical plant cell contains about 10 to 100 chloroplasts. The chloroplast is enclosed by a membrane. This membrane is composed of a phospholipid inner membrane, a phospholipid outer membrane, and an intermembrane space between them. Within the membrane is an aqueous fluid called the stroma. The stroma contains stacks (grana) of thylakoids, which are the site of photosynthesis. The thylakoids are flattened disks, bounded by a membrane with a lumen or thylakoid space within it. The site of photosynthesis is the thylakoid membrane, which contains integral and peripheral membrane protein complexes, including the pigments that absorb light energy, which form the photosystems.

Plants absorb light primarily using the pigment chlorophyll, which is the reason that most plants have a green color. Besides chlorophyll, plants also use pigments such as carotenes and xanthophylls.[20] Algae also use chlorophyll, but various other pigments are present as phycocyanin, carotenes, and xanthophylls in green algae, phycoerythrin in red algae (rhodophytes) and fucoxanthin in brown algae and diatoms resulting in a wide variety of colors.

These pigments are embedded in plants and algae in special antenna-proteins. In such proteins all the pigments are ordered to work well together. Such a protein is also called a light-harvesting complex.

Although all cells in the green parts of a plant have chloroplasts, most of the energy is captured in the leaves, except in certain species adapted to conditions of strong sunlight and aridity, such as many Euphorbia and Cactus species, whose main photosynthetic organs are their stems. The cells in the interior tissues of a leaf, called the mesophyll, can contain between 450,000 and 800,000 chloroplasts for every square millimeter of leaf. The surface of the leaf is uniformly coated with a water-resistant waxy cuticle that protects the leaf from excessive evaporation of water and decreases the absorption of ultraviolet or blue light to reduce heating. The transparent epidermis layer allows light to pass through to the palisade mesophyll cells where most of the photosynthesis takes place.

Light reactions

In the light reactions, one molecule of the pigment chlorophyll absorbs one photon and loses one electron. This electron is passed to a modified form of chlorophyll called pheophytin, which passes the electron to a quinone molecule, allowing the start of a flow of electrons down an electron transport chain that leads to the ultimate reduction of NADP to NADPH. In addition, this creates a proton gradient across the chloroplast membrane; its dissipation is used by ATP synthase for the concomitant synthesis of ATP. The chlorophyll molecule regains the lost electron from a water molecule through a process called photolysis, which releases a dioxygen (O2) molecule. The overall equation for the light-dependent reactions under the conditions of non-cyclic electron flow in green plants is:[21]

- 2 H2O + 2 NADP+ + 3 ADP + 3 Pi + light → 2 NADPH + 2 H+ + 3 ATP + O2

Not all wavelengths of light can support photosynthesis. The photosynthetic action spectrum depends on the type of accessory pigments present. For example, in green plants, the action spectrum resembles the absorption spectrum for chlorophylls and carotenoids with peaks for violet-blue and red light. In red algae, the action spectrum overlaps with the absorption spectrum of phycobilins for red blue-green light, which allows these algae to grow in deeper waters that filter out the longer wavelengths used by green plants. The non-absorbed part of the light spectrum is what gives photosynthetic organisms their color (e.g., green plants, red algae, purple bacteria) and is the least effective for photosynthesis in the respective organisms.

Z scheme

In plants, light-dependent reactions occur in the thylakoid membranes of the chloroplasts and use light energy to synthesize ATP and NADPH. The light-dependent reaction has two forms: cyclic and non-cyclic. In the non-cyclic reaction, the photons are captured in the light-harvesting antenna complexes of photosystem II by chlorophyll and other accessory pigments (see diagram at right). When a chlorophyll molecule at the core of the photosystem II reaction center obtains sufficient excitation energy from the adjacent antenna pigments, an electron is transferred to the primary electron-acceptor molecule, pheophytin, through a process called photoinduced charge separation. These electrons are shuttled through an electron transport chain, the so-called Z-scheme shown in the diagram, that initially functions to generate a chemiosmotic potential across the membrane. An ATP synthase enzyme uses the chemiosmotic potential to make ATP during photophosphorylation, whereas NADPH is a product of the terminal redox reaction in the Z-scheme. The electron enters a chlorophyll molecule in Photosystem I. The electron is excited due to the light absorbed by the photosystem. A second electron carrier accepts the electron, which again is passed down lowering energies of electron acceptors. The energy created by the electron acceptors is used to move hydrogen ions across the thylakoid membrane into the lumen. The electron is used to reduce the co-enzyme NADP, which has functions in the light-independent reaction. The cyclic reaction is similar to that of the non-cyclic, but differs in the form that it generates only ATP, and no reduced NADP (NADPH) is created. The cyclic reaction takes place only at photosystem I. Once the electron is displaced from the photosystem, the electron is passed down the electron acceptor molecules and returns to photosystem I, from where it was emitted, hence the name cyclic reaction.

Water photolysis

The NADPH is the main reducing agent in chloroplasts, providing a source of energetic electrons to other reactions. Its production leaves chlorophyll with a deficit of electrons (oxidized), which must be obtained from some other reducing agent. The excited electrons lost from chlorophyll in photosystem I are replaced from the electron transport chain by plastocyanin. However, since photosystem II includes the first steps of the Z-scheme, an external source of electrons is required to reduce its oxidized chlorophyll a molecules. The source of electrons in green-plant and cyanobacterial photosynthesis is water. Two water molecules are oxidized by four successive charge-separation reactions by photosystem II to yield a molecule of diatomic oxygen and four hydrogen ions; the electron yielded in each step is transferred to a redox-active tyrosine residue that then reduces the photoxidized paired-chlorophyll a species called P680 that serves as the primary (light-driven) electron donor in the photosystem II reaction center. The oxidation of water is catalyzed in photosystem II by a redox-active structure that contains four manganese ions and a calcium ion; this oxygen-evolving complex binds two water molecules and stores the four oxidizing equivalents that are required to drive the water-oxidizing reaction. Photosystem II is the only known biological enzyme that carries out this oxidation of water. The hydrogen ions contribute to the transmembrane chemiosmotic potential that leads to ATP synthesis. Oxygen is a waste product of light-dependent reactions, but the majority of organisms on Earth use oxygen for cellular respiration, including photosynthetic organisms.[22][23]

Light-independent reactions

Calvin cycle

In the light-independent (or "dark") reactions, the enzyme RuBisCO captures CO2 from the atmosphere and in a process that requires the newly formed NADPH, called the Calvin-Benson Cycle, releases three-carbon sugars, which are later combined to form sucrose and starch. The overall equation for the light-independent reactions in green plants is:[21]: 128

- 3 CO2 + 9 ATP + 6 NADPH + 6 H+ → C3H6O3-phosphate + 9 ADP + 8 Pi + 6 NADP+ + 3 H2O

To be more specific, carbon fixation produces an intermediate product, which is then converted to the final carbohydrate products. The carbon skeletons produced by photosynthesis are then variously used to form other organic compounds, such as the building material cellulose, as precursors for lipid and amino acid biosynthesis, or as a fuel in cellular respiration. The latter occurs not only in plants but also in animals when the energy from plants gets passed through a food chain.

The fixation or reduction of carbon dioxide is a process in which carbon dioxide combines with a five-carbon sugar, ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate (RuBP), to yield two molecules of a three-carbon compound, glycerate 3-phosphate (GP), also known as 3-phosphoglycerate (PGA). GP, in the presence of ATP and NADPH from the light-dependent stages, is reduced to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate (G3P). This product is also referred to as 3-phosphoglyceraldehyde (PGAL) or even as triose phosphate. Triose is a 3-carbon sugar (see carbohydrates). Most (5 out of 6 molecules) of the G3P produced is used to regenerate RuBP so the process can continue (see Calvin-Benson cycle). The 1 out of 6 molecules of the triose phosphates not "recycled" often condense to form hexose phosphates, which ultimately yield sucrose, starch and cellulose. The sugars produced during carbon metabolism yield carbon skeletons that can be used for other metabolic reactions like the production of amino acids and lipids.

Carbon concentrating mechanisms

On land

In hot and dry conditions, plants close their stomata to prevent the loss of water. Under these conditions, CO2 will decrease, and oxygen gas, produced by the light reactions of photosynthesis, will decrease in the stem, not leaves, causing an increase of photorespiration by the oxygenase activity of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase and decrease in carbon fixation. Some plants have evolved mechanisms to increase the CO2 concentration in the leaves under these conditions.[24]

C4 plants chemically fix carbon dioxide in the cells of the mesophyll by adding it to the three-carbon molecule phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP), a reaction catalyzed by an enzyme called PEP carboxylase, creating the four-carbon organic acid oxaloacetic acid. Oxaloacetic acid or malate synthesized by this process is then translocated to specialized bundle sheath cells where the enzyme RuBisCO and other Calvin cycle enzymes are located, and where CO2 released by decarboxylation of the four-carbon acids is then fixed by RuBisCO activity to the three-carbon sugar 3-phosphoglyceric acids. The physical separation of RuBisCO from the oxygen-generating light reactions reduces photorespiration and increases CO2 fixation and, thus, photosynthetic capacity of the leaf.[25] C4 plants can produce more sugar than C3 plants in conditions of high light and temperature. Many important crop plants are C4 plants, including maize, sorghum, sugarcane, and millet. Plants that do not use PEP-carboxylase in carbon fixation are called C3 plants because the primary carboxylation reaction, catalyzed by RuBisCO, produces the three-carbon sugar 3-phosphoglyceric acids directly in the Calvin-Benson cycle. Over 90% of plants use C3 carbon fixation, compared to 3% that use C4 carbon fixation.;[26] however, the fact that C4 has evolved in over 60 plant lineages makes it a striking example of convergent evolution.[24]

Xerophytes, such as cacti and most succulents, also use PEP carboxylase to capture carbon dioxide in a process called Crassulacean acid metabolism (CAM). In contrast to C4 metabolism, which physically separates the CO2 fixation to PEP from the Calvin cycle, CAM temporally separates these two processes. CAM plants have a different leaf anatomy from C3 plants, and fix the CO2 at night, when their stomata are open. CAM plants store the CO2 mostly in the form of malic acid via carboxylation of phosphoenolpyruvate to oxaloacetate, which is then reduced to malate. Decarboxylation of malate during the day releases CO2 inside the leaves, thus allowing carbon fixation to 3-phosphoglycerate by RuBisCO. Sixteen thousand species of plants use CAM.[27]

In water

Cyanobacteria possess carboxysomes, which increase the concentration of CO2 around RuBisCO to increase the rate of photosynthesis. An enzyme, carbonic anhydrase, located within the carboxysome releases CO2 from the dissolved hydrocarbonate ions (HCO3–). Before the CO2 diffuses out it is quickly sponged up by RuBisCO, which is concentrated within the carboxysomes. HCO3– ions are made from CO2 outside the cell by another carbonic anhydrase and are actively pumped into the cell by a membrane protein. They cannot cross the membrane as they are charged, and within the cytosol they turn back into CO2 very slowly without the help of carbonic anhydrase. This causes the HCO3– ions to accumulate within the cell from where they diffuse into the carboxysomes.[28] Pyrenoids in algae and hornworts also act to concentrate CO2 around rubisco.[29]

Order and kinetics

The overall process of photosynthesis takes place in four stages:[13]

| Stage | Description | Time scale |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Energy transfer in antenna chlorophyll (thylakoid membranes) | femtosecond to picosecond |

| 2 | Transfer of electrons in photochemical reactions (thylakoid membranes) | picosecond to nanosecond |

| 3 | Electron transport chain and ATP synthesis (thylakoid membranes) | microsecond to millisecond |

| 4 | Carbon fixation and export of stable products | millisecond to second |

Efficiency

Plants usually convert light into chemical energy with a photosynthetic efficiency of 3–6%.[30] Absorbed light that is unconverted is dissipated primarily as heat, with a small fraction (1-2%) [31] re-emitted as chlorophyll fluorescence at longer (redder) wavelengths.

Actual plants' photosynthetic efficiency varies with the frequency of the light being converted, light intensity, temperature and proportion of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, and can vary from 0.1% to 8%.[32] By comparison, solar panels convert light into electric energy at an efficiency of approximately 6–20% for mass-produced panels, and above 40% in laboratory devices.

Photosynthesis measurement systems are not designed to directly measure the amount of light absorbed by the leaf. Nevertheless, the light response curves that systems like the LCpro-SD produce, do allow comparisons in photosynthetic efficiency between plants.

Evolution

Early photosynthetic systems, such as those from green and purple sulfur and green and purple nonsulfur bacteria, are thought to have been anoxygenic, using various molecules as electron donors. Green and purple sulfur bacteria are thought to have used hydrogen and sulfur as an electron donor. Green nonsulfur bacteria used various amino and other organic acids. Purple nonsulfur bacteria used a variety of nonspecific organic molecules. The use of these molecules is consistent with the geological evidence that the atmosphere was highly reduced at that time.[citation needed]

Fossils of what are thought to be filamentous photosynthetic organisms have been dated at 3.4 billion years old.[33][34]

The main source of oxygen in the atmosphere is oxygenic photosynthesis, and its first appearance is sometimes referred to as the oxygen catastrophe. Geological evidence suggests that oxygenic photosynthesis, such as that in cyanobacteria, became important during the Paleoproterozoic era around 2 billion years ago. Modern photosynthesis in plants and most photosynthetic prokaryotes is oxygenic. Oxygenic photosynthesis uses water as an electron donor, which is oxidized to molecular oxygen (O

2) in the photosynthetic reaction center.

Symbiosis and the origin of chloroplasts

Several groups of animals have formed symbiotic relationships with photosynthetic algae. These are most common in corals, sponges and sea anemones. It is presumed that this is due to the particularly simple body plans and large surface areas of these animals compared to their volumes.[35] In addition, a few marine mollusks Elysia viridis and Elysia chlorotica also maintain a symbiotic relationship with chloroplasts they capture from the algae in their diet and then store in their bodies. This allows the mollusks to survive solely by photosynthesis for several months at a time.[36][37] Some of the genes from the plant cell nucleus have even been transferred to the slugs, so that the chloroplasts can be supplied with proteins that they need to survive.[38]

An even closer form of symbiosis may explain the origin of chloroplasts. Chloroplasts have many similarities with photosynthetic bacteria, including a circular chromosome, prokaryotic-type ribosomes, and similar proteins in the photosynthetic reaction center.[39][40] The endosymbiotic theory suggests that photosynthetic bacteria were acquired (by endocytosis) by early eukaryotic cells to form the first plant cells. Therefore, chloroplasts may be photosynthetic bacteria that adapted to life inside plant cells. Like mitochondria, chloroplasts still possess their own DNA, separate from the nuclear DNA of their plant host cells and the genes in this chloroplast DNA resemble those in cyanobacteria.[41] DNA in chloroplasts codes for redox proteins such as photosynthetic reaction centers. The CoRR Hypothesis proposes that this Co-location is required for Redox Regulation.

Cyanobacteria and the evolution of photosynthesis

The biochemical capacity to use water as the source for electrons in photosynthesis evolved once, in a common ancestor of extant cyanobacteria. The geological record indicates that this transforming event took place early in Earth's history, at least 2450–2320 million years ago (Ma), and, it is speculated, much earlier.[42][43] Available evidence from geobiological studies of Archean (>2500 Ma) sedimentary rocks indicates that life existed 3500 Ma, but the question of when oxygenic photosynthesis evolved is still unanswered. A clear paleontological window on cyanobacterial evolution opened about 2000 Ma, revealing an already-diverse biota of blue-greens. Cyanobacteria remained principal primary producers throughout the Proterozoic Eon (2500–543 Ma), in part because the redox structure of the oceans favored photoautotrophs capable of nitrogen fixation.[citation needed] Green algae joined blue-greens as major primary producers on continental shelves near the end of the Proterozoic, but only with the Mesozoic (251–65 Ma) radiations of dinoflagellates, coccolithophorids, and diatoms did primary production in marine shelf waters take modern form. Cyanobacteria remain critical to marine ecosystems as primary producers in oceanic gyres, as agents of biological nitrogen fixation, and, in modified form, as the plastids of marine algae.[44]

A 2010 study by researchers at Tel Aviv University discovered that the Oriental hornet (Vespa orientalis) converts sunlight into electric power using a pigment called xanthopterin. This is the first scientific evidence of a member of the animal kingdom engaging in photosynthesis.[45]

Discovery

Although some of the steps in photosynthesis are still not completely understood, the overall photosynthetic equation has been known since the 19th century.

Jan van Helmont began the research of the process in the mid-17th century when he carefully measured the mass of the soil used by a plant and the mass of the plant as it grew. After noticing that the soil mass changed very little, he hypothesized that the mass of the growing plant must come from the water, the only substance he added to the potted plant. His hypothesis was partially accurate — much of the gained mass also comes from carbon dioxide as well as water. However, this was a signaling point to the idea that the bulk of a plant's biomass comes from the inputs of photosynthesis, not the soil itself.

Joseph Priestley, a chemist and minister, discovered that, when he isolated a volume of air under an inverted jar, and burned a candle in it, the candle would burn out very quickly, much before it ran out of wax. He further discovered that a mouse could similarly "injure" air. He then showed that the air that had been "injured" by the candle and the mouse could be restored by a plant.

In 1778, Jan Ingenhousz, court physician to the Austrian Empress, repeated Priestley's experiments. He discovered that it was the influence of sunlight on the plant that could cause it to revive a mouse in a matter of hours.

In 1796, Jean Senebier, a Swiss pastor, botanist, and naturalist, demonstrated that green plants consume carbon dioxide and release oxygen under the influence of light. Soon afterward, Nicolas-Théodore de Saussure showed that the increase in mass of the plant as it grows could not be due only to uptake of CO2 but also to the incorporation of water. Thus, the basic reaction by which photosynthesis is used to produce food (such as glucose) was outlined.

Cornelis Van Niel made key discoveries explaining the chemistry of photosynthesis. By studying purple sulfur bacteria and green bacteria he was the first scientist to demonstrate that photosynthesis is a light-dependent redox reaction, in which hydrogen reduces carbon dioxide.

Robert Emerson discovered two light reactions by testing plant productivity using different wavelengths of light. With the red alone, the light reactions were suppressed. When blue and red were combined, the output was much more substantial. Thus, there were two photosystems, one absorbing up to 600 nm wavelengths, the other up to 700 nm. The former is known as PSII, the latter is PSI. PSI contains only chlorophyll a, PSII contains primarily chlorophyll a with most of the available chlorophyll b, among other pigment. These include phycobilins, which are the red and blue pigments of red and blue algae respectively, and fucoxanthol for brown algae and diatoms. The process is most productive when absorption of quanta are equal in both the PSII and PSI, assuring that input energy from the antenna complex is divided between the PSI and PSII system, which in turn powers the photochemistry.[13]

Robert Hill thought that a complex of reactions consisting of an intermediate to cytochrome b6 (now a plastoquinone), another is from cytochrome f to a step in the carbohydrate-generating mechanisms. These are linked by plastoquinone, which does require energy to reduce cytochrome f for it is a sufficient reductant. Further experiments to prove that the oxygen developed during the photosynthesis of green plants came from water, were performed by Hill in 1937 and 1939. He showed that isolated chloroplasts give off oxygen in the presence of unnatural reducing agents like iron oxalate, ferricyanide or benzoquinone after exposure to light. The Hill reaction is as follows:

- 2 H2O + 2 A + (light, chloroplasts) → 2 AH2 + O2

where A is the electron acceptor. Therefore, in light, the electron acceptor is reduced and oxygen is evolved.

Samuel Ruben and Martin Kamen used radioactive isotopes to determine that the oxygen liberated in photosynthesis came from the water.

Melvin Calvin and Andrew Benson, along with James Bassham, elucidated the path of carbon assimilation (the photosynthetic carbon reduction cycle) in plants. The carbon reduction cycle is known as the Calvin cycle, which ignores the contribution of Bassham and Benson. Many scientists refer to the cycle as the Calvin-Benson Cycle, Benson-Calvin, and some even call it the Calvin-Benson-Bassham (or CBB) Cycle.

Nobel Prize-winning scientist Rudolph A. Marcus was able to discover the function and significance of the electron transport chain.

Otto Heinrich Warburg and Dean Burk discovered the I-quantum photosynthesis reaction that splits the CO2, activated by the respiration.[46]

Louis N.M. Duysens and Jan Amesz discovered that chlorophyll a will absorb one light, oxidize cytochrome f, chlorophyll a (and other pigments) will absorb another light, but will reduce this same oxidized cytochrome, stating the two light reactions are in series.

Development of the concept

In 1893, Charles Reid Barnes proposed two terms, photosyntax and photosynthesis, for the biological process of synthesis of complex carbon compounds out of carbonic acid, in the presence of chlorophyll, under the influence of light. Over time, the term photosynthesis came into common usage as the term of choice. Later discovery of anoxygenic photosynthetic bacteria and photophosphorylation necessitated redefinition of the term.[47]

Factors

There are three main factors affecting photosynthesis and several corollary factors. The three main are:

- Light irradiance and wavelength

- Carbon dioxide concentration

- Temperature.

Light intensity (irradiance), wavelength and temperature

In the early 20th century, Frederick Blackman and Gabrielle Matthaei investigated the effects of light intensity (irradiance) and temperature on the rate of carbon assimilation.

- At constant temperature, the rate of carbon assimilation varies with irradiance, initially increasing as the irradiance increases. However, at higher irradiance, this relationship no longer holds and the rate of carbon assimilation reaches a plateau.

- At constant irradiance, the rate of carbon assimilation increases as the temperature is increased over a limited range. This effect is seen only at high irradiance levels. At low irradiance, increasing the temperature has little influence on the rate of carbon assimilation.

These two experiments illustrate vital points: First, from research it is known that, in general, photochemical reactions are not affected by temperature. However, these experiments clearly show that temperature affects the rate of carbon assimilation, so there must be two sets of reactions in the full process of carbon assimilation. These are, of course, the light-dependent 'photochemical' stage and the light-independent, temperature-dependent stage. Second, Blackman's experiments illustrate the concept of limiting factors. Another limiting factor is the wavelength of light. Cyanobacteria, which reside several meters underwater, cannot receive the correct wavelengths required to cause photoinduced charge separation in conventional photosynthetic pigments. To combat this problem, a series of proteins with different pigments surround the reaction center. This unit is called a phycobilisome.

Carbon dioxide levels and photorespiration

As carbon dioxide concentrations rise, the rate at which sugars are made by the light-independent reactions increases until limited by other factors. RuBisCO, the enzyme that captures carbon dioxide in the light-independent reactions, has a binding affinity for both carbon dioxide and oxygen. When the concentration of carbon dioxide is high, RuBisCO will fix carbon dioxide. However, if the carbon dioxide concentration is low, RuBisCO will bind oxygen instead of carbon dioxide. This process, called photorespiration, uses energy, but does not produce sugars.

RuBisCO oxygenase activity is disadvantageous to plants for several reasons:

- One product of oxygenase activity is phosphoglycolate (2 carbon) instead of 3-phosphoglycerate (3 carbon). Phosphoglycolate cannot be metabolized by the Calvin-Benson cycle and represents carbon lost from the cycle. A high oxygenase activity, therefore, drains the sugars that are required to recycle ribulose 5-bisphosphate and for the continuation of the Calvin-Benson cycle.

- Phosphoglycolate is quickly metabolized to glycolate that is toxic to a plant at a high concentration; it inhibits photosynthesis.

- Salvaging glycolate is an energetically expensive process that uses the glycolate pathway, and only 75% of the carbon is returned to the Calvin-Benson cycle as 3-phosphoglycerate. The reactions also produce ammonia (NH3), which is able to diffuse out of the plant, leading to a loss of nitrogen.

- A highly simplified summary is:

- 2 glycolate + ATP → 3-phosphoglycerate + carbon dioxide + ADP + NH3

The salvaging pathway for the products of RuBisCO oxygenase activity is more commonly known as photorespiration, since it is characterized by light-dependent oxygen consumption and the release of carbon dioxide.

See also

- Jan Anderson (scientist)

- Artificial photosynthesis

- Calvin-Benson cycle

- Carbon fixation

- Cellular respiration

- Chemosynthesis

- Light-dependent reaction

- Photobiology

- Photoinhibition

- Photosynthetic reaction center

- Photosynthetically active radiation

- Photosystem

- Photosystem I

- Photosystem II

- Quantum biology

- Red edge

- Vitamin D

References

- ^ "photosynthesis". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ φῶς. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project

- ^ σύνθεσις. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project

- ^ a b Bryant DA, Frigaard NU (2006). "Prokaryotic photosynthesis and phototrophy illuminated". Trends Microbiol. 14 (11): 488–96. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2006.09.001. PMID 16997562.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Reece J, Urry L, Cain M, Wasserman S, Minorsky P, Jackson R. Biology (International ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education. pp. 235, 244. ISBN 0-321-73975-2.

This initial incorporation of carbon into organic compounds is known as carbon fixation.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Olson JM (2006). "Photosynthesis in the Archean era". Photosyn. Res. 88 (2): 109–17. doi:10.1007/s11120-006-9040-5. PMID 16453059.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Buick R (2008). "When did oxygenic photosynthesis evolve?". Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond., B, Biol. Sci. 363 (1504): 2731–43. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0041. PMC 2606769. PMID 18468984.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Nealson KH, Conrad PG (1999). "Life: past, present and future". Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond., B, Biol. Sci. 354 (1392): 1923–39. doi:10.1098/rstb.1999.0532. PMC 1692713. PMID 10670014.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Whitmarsh J, Govindjee (1999). "The photosynthetic process". In Singhal GS, Renger G, Sopory SK, Irrgang KD, Govindjee (ed.). Concepts in photobiology: photosynthesis and photomorphogenesis. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers. pp. 11–51. ISBN 0-7923-5519-9.

100 x 1015 grams of carbon/year fixed by photosynthetic organisms which is equivalent to 4 x 1018 kJ/yr = 4 x 1021J/yr of free energy stored as reduced carbon; (4 x 1018 kJ/yr) / (31,556,900 sec/yr) = 1.27 x 1014 J/yr; (1.27 x 1014 J/yr) / (1012 J/sec / TW) = 127 TW.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Steger U, Achterberg W, Blok K, Bode H, Frenz W, Gather C, Hanekamp G, Imboden D, Jahnke M, Kost M, Kurz R, Nutzinger HG, Ziesemer T (2005). Sustainable development and innovation in the energy sector. Berlin: Springer. p. 32. ISBN 3-540-23103-X.

The average global rate of photosynthesis is 130 TW (1 TW = 1 terawatt = 1012 watt).

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "World Consumption of Primary Energy by Energy Type and Selected Country Groups, 1980–2004" (XLS). Energy Information Administration. July 31, 2006. Retrieved 2007-01-20.

- ^ Field CB, Behrenfeld MJ, Randerson JT, Falkowski P (1998). "Primary production of the biosphere: integrating terrestrial and oceanic components". Science. 281 (5374): 237–40. Bibcode:1998Sci...281..237F. doi:10.1126/science.281.5374.237. PMID 9657713.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c "Photosynthesis". McGraw-Hill Encyclopedia of Science & Technology. Vol. 13. New York: McGraw-Hill. 2007. ISBN 0-07-144143-3.

- ^ Anaerobic Photosynthesis, Chemical & Engineering News, 86, 33, August 18, 2008, p. 36

- ^ Kulp TR, Hoeft SE, Asao M, Madigan MT, Hollibaugh JT, Fisher JC, Stolz JF, Culbertson CW, Miller LG, Oremland RS (2008). "Arsenic(III) fuels anoxygenic photosynthesis in hot spring biofilms from Mono Lake, California". Science. 321 (5891): 967–70. Bibcode:2008Sci...321..967K. doi:10.1126/science.1160799. PMID 18703741.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Scientists discover unique microbe in California's largest lake". Retrieved 2009-07-20.

- ^ Tavano CL, Donohue TJ (2006). "Development of the bacterial photosynthetic apparatus". Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 9 (6): 625–31. doi:10.1016/j.mib.2006.10.005. PMC 2765710. PMID 17055774.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Mullineaux CW (1999). "The thylakoid membranes of cyanobacteria: structure, dynamics and function". Australian Journal of Plant Physiology. 26 (7): 671–677. doi:10.1071/PP99027.

- ^ Sener MK, Olsen JD, Hunter CN, Schulten K (2007). "Atomic-level structural and functional model of a bacterial photosynthetic membrane vesicle". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 (40): 15723–8. Bibcode:2007PNAS..10415723S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0706861104. PMC 2000399. PMID 17895378.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Campbell NA, Williamson B, Heyden RJ (2006). Biology Exploring Life. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-250882-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Raven PH, Evert RF, Eichhorn SE (2005). Biology of Plants, (7th ed.). New York: W.H. Freeman and Company Publishers. pp. 124–127. ISBN 0-7167-1007-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Yachandra Group Home page".

- ^ Pushkar Y, Yano J, Sauer K, Boussac A, Yachandra VK (2008). "Structural changes in the Mn4Ca cluster and the mechanism of photosynthetic water splitting". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105 (6): 1879–84. Bibcode:2008PNAS..105.1879P. doi:10.1073/pnas.0707092105. PMC 2542863. PMID 18250316.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Williams BP, Johnston IG, Covshoff S, Hibberd JM (2013). "Phenotypic landscape inference reveals multiple evolutionary paths to C₄ photosynthesis". eLife. 2: e00961. doi:10.7554/eLife.00961.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ L. Taiz, E. Zeiger (2006). Plant Physiology (4 ed.). Sinauer Associates. ISBN 978-0-87893-856-8.

- ^ Monson RK, Sage RF (1999). "16". C₄ plant biology. Boston: Academic Press. pp. 551–580. ISBN 0-12-614440-0.

- ^ Dodd AN, Borland AM, Haslam RP, Griffiths H, Maxwell K (2002). "Crassulacean acid metabolism: plastic, fantastic". J. Exp. Bot. 53 (369): 569–80. doi:10.1093/jexbot/53.369.569. PMID 11886877.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Badger, M. R.; Price, GD (2003). "CO2 concentrating mechanisms in cyanobacteria: molecular components, their diversity and evolution". Journal of Experimental Botany. 54 (383): 609–22. doi:10.1093/jxb/erg076. PMID 12554704.

- ^ Badger MR, Andrews JT, Whitney SM, Ludwig M, Yellowlees DC, Leggat W, Price GD (1998). "The diversity and coevolution of Rubisco, plastids, pyrenoids, and chloroplast-based CO2-concentrating mechanisms in algae". Canadian Journal of Botany. 76 (6): 1052–1071. doi:10.1139/b98-074. ISSN 1480-3305 0008-4026, 1480-3305.

{{cite journal}}: Check|issn=value (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Chapter 1 – Biological energy production">Miyamoto K. "Chapter 1 – Biological energy production". Renewable biological systems for alternative sustainable energy production (FAO Agricultural Services Bulletin – 128). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved 2009-01-04.

- ^ "Chlorophyll fluorescence—a practical guide". Oxford: Journal of Experimental Botany.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Govindjee, What is photosynthesis?

- ^ Photosynthesis got a really early start, New Scientist, 2 October 2004

- ^ Revealing the dawn of photosynthesis, New Scientist, 19 August 2006

- ^ Venn AA, Loram JE, Douglas AE (2008). "Photosynthetic symbioses in animals". J. Exp. Bot. 59 (5): 1069–80. doi:10.1093/jxb/erm328. PMID 18267943.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rumpho ME, Summer EJ, Manhart JR (2000). "Solar-powered sea slugs. Mollusc/algal chloroplast symbiosis". Plant Physiol. 123 (1): 29–38. doi:10.1104/pp.123.1.29. PMC 1539252. PMID 10806222.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Muscatine L, Greene RW (1973). "Chloroplasts and algae as symbionts in molluscs". Int. Rev. Cytol. International Review of Cytology. 36: 137–69. doi:10.1016/S0074-7696(08)60217-X. ISBN 9780123643360. PMID 4587388.

- ^ Rumpho ME, Worful JM, Lee J, Kannan K, Tyler MS, Bhattacharya D, Moustafa A, Manhart JR (2008). "Horizontal gene transfer of the algal nuclear gene psbO to the photosynthetic sea slug Elysia chlorotica". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105 (46): 17867–71. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10517867R. doi:10.1073/pnas.0804968105. PMC 2584685. PMID 19004808.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Douglas SE (1998). "Plastid evolution: origins, diversity, trends". Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 8 (6): 655–61. doi:10.1016/S0959-437X(98)80033-6. PMID 9914199.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Reyes-Prieto A, Weber AP, Bhattacharya D (2007). "The origin and establishment of the plastid in algae and plants". Annu. Rev. Genet. 41: 147–68. doi:10.1146/annurev.genet.41.110306.130134. PMID 17600460.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Raven JA, Allen JF (2003). "Genomics and chloroplast evolution: what did cyanobacteria do for plants?". Genome Biol. 4 (3): 209. doi:10.1186/gb-2003-4-3-209. PMC 153454. PMID 12620099.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Akiko Tomitani (2006). "The evolutionary diversification of cyanobacteria: Molecular–phylogenetic and paleontological perspectives". PNAS. 103 (14): 5442–5447. doi:10.1073/pnas.0600999103.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Cyanobacteria: Fossil Record". Ucmp.berkeley.edu. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- ^ Herrero A, Flores E (2008). The Cyanobacteria: Molecular Biology, Genomics and Evolution (1st ed.). Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-15-8.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1007/s00114-010-0728-1, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1007/s00114-010-0728-1instead. - ^ Otto Warburg – Biography. Nobelprize.org (1970-08-01). Retrieved on 2011-11-03.

- ^ Gest, Howard (2002). History of the word photosynthesis and evolution of its definition. Photosynthesis Research 73(1-3): 7-10.

Further reading

Books

- Asimov, Isaac (1968). Photosynthesis. New York, London: Basic Books, Inc. ISBN 0-465-05703-9.

- Bidlack JE; Stern KR, Jansky S (2003). Introductory plant biology. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-290941-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Blankenship RE (2008). Molecular Mechanisms of Photosynthesis (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons Inc. ISBN 0-470-71451-4.

- Govindjee (1975). Bioenergetics of photosynthesis. Boston: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-294350-3.

- Govindjee Beatty JT,Gest H, Allen JF (2006). Discoveries in Photosynthesis. Advances in Photosynthesis and Respiration. Vol. 20. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 1-4020-3323-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Gregory RL (1971). Biochemistry of photosynthesis. New York: Wiley-Interscience. ISBN 0-471-32675-5.

- Rabinowitch E, Govindjee (1969). Photosynthesis. London: J. Wiley. ISBN 0-471-70424-5.

- Reece, J, Campbell, N (2005). Biology. San Francisco: Pearson, Benjamin Cummings. ISBN 0-8053-7146-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Papers

- Gupta RS, Mukhtar T, Singh B (1999). "Evolutionary relationships among photosynthetic prokaryotes (Heliobacterium chlorum, Chloroflexus aurantiacus, cyanobacteria, Chlorobium tepidum and proteobacteria): implications regarding the origin of photosynthesis". Mol. Microbiol. 32 (5): 893–906. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01417.x. PMID 10361294.

implications regarding the origin of photosynthesis

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Blankenship RE (1992). "Origin and early evolution of photosynthesis". Photosyn. Res. 33 (2): 91–111. doi:10.1007/BF00039173. PMID 11538390.

- Rutherford AW, Faller P (2003). "Photosystem II: evolutionary perspectives". Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond., B, Biol. Sci. 358 (1429): 245–53. doi:10.1098/rstb.2002.1186. PMC 1693113. PMID 12594932.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)

External links

- A collection of photosynthesis pages for all levels from a renowned expert (Govindjee)

- In depth, advanced treatment of photosynthesis, also from Govindjee

- Science Aid: Photosynthesis Article appropriate for high school science

- Metabolism, Cellular Respiration and Photosynthesis – The Virtual Library of Biochemistry and Cell Biology

- Overall examination of Photosynthesis at an intermediate level

- Overall Energetics of Photosynthesis

- Photosynthesis Discovery Milestones – experiments and background

- The source of oxygen produced by photosynthesis Interactive animation, a textbook tutorial

- Jessica Marshall (2011-03-29). "First practical artificial leaf makes debut". Discovery News.

- Photosynthesis – Light Dependent & Light Independent Stages

- Khan Academy, video introduction

Template:Link GA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA