Carlisle Indian Industrial School

Carlisle Indian School | |

Carlisle Indian School | |

| Location | Carlisle, Pennsylvania |

|---|---|

| Area | 24.5 acres (9.9 ha) |

| Built | 1879 |

| Architectural style | Colonial Revival |

| NRHP reference No. | 66000658[1] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966 |

| Designated NHL | July 4, 1961[2] |

Summary

Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, was the flagship Indian boarding school in the United States from 1879 through 1918. Founded in 1879 by Captain Richard Henry Pratt, Carlisle was the the first federally funded off-reservation Indian boarding school. The Carlisle Indian School was located in a rural Eastern environment, free of the West’s anti-Indian prejudices and free from the influences of native cultures.[3] Carlisle was founded on principle that Native Americans are the equals of whites, and that Native American children immersed in white culture would learn skills to advance in society. Pratt had great respect for Native Americans and offered a path of opportunity and hope at a time people believed Native Americans were a vanishing race whose only hope for survival was rapid cultural transformation.[4] Carlisle set the bar for 26 Bureau of Indian Affairs boarding schools in 15 states and territories and hundreds of private boarding schools sponsored by religious denominations. From 1879 until 1918, over 10,000 Native American children from 140 tribes attended Carlisle.[5] Tribes with the with largest number of students included the Lakota, Ojibwe, Seneca, Oneida, Cherokee, Apache, Cheyenne, and Alaska Native.[6] The Carlisle Indian School exemplified Progressive Era values.[7] Some Native Americans considered Carlisle to provide an excellent education. The family tradition of Carlisle alumni as "Harvard style" is one of pride and stories of opportunity and success.[8]

The Indian Harvard

The Carlisle Indian School was the exemplar in the Progressive Era fight for the image of Native Americans. Over the course of 40 years, 1879-1918, Carlisle evolved beyond an industrial trade school. Nearby historic Dickinson College provided Carlisle Indian School students with visiting professors, access to the Dickinson Preparatory School ("Conway Hall") and college level education. The Dickinson School of Law was another resource to the Carlisle Indian School and a number of Carlisle students attended. Carlisle was a unique school, and is considered by many Native Americans like going to Harvard, Yale or Oxford.[9] The family tradition of Carlisle alumni as “Harvard style” is one of pride and stories of opportunity and success.[10] Students excelled at music, debating, journalism and sports, and were offered internships and a Summer Outing Program living with white families and earning wages. The Carlisle Indian Band, Carlisle Cadets and Carlisle Indians football team earned national reputations. The Carlisle Indian Band performed at world fairs, the Paris Exposition and every national presidential inaugural celebration until the school closed. The Carlisle Cadets at arms marched in parades. The Carlisle Indians were a national football powerhouse in early 20th century and competed and won games against Harvard, Pennsylvania, Cornell, Dartmouth, Yale, Princeton, Brown, Army and Navy. During the program's 25 years, the Carlisle Indians compiled a 167–88–13 record and 0.647 winning percentage, the most successful defunct major college football program. In 1911 legendary athlete Jim Thorpe and coach Pop Warner led the Carlisle Indians to a 18–15 upset of Harvard.[11] Carlisle produced many accomplished Native alumni.[12]

Richard Henry Pratt

Richard Henry Pratt served in the Civil War. After the war, Lt. Pratt led the 10th Cavalry Regiment, who became known as Buffalo Soldiers, in the southern plains of the United States. One of Pratt's jobs was to command Native Americans who were enlisted scouts for the 10th Cavalry. In 1875, Pratt transported a small group of 72 Indian prisoners, to Fort Marion (Castillo de San Marcos), an old Spanish fort in St. Augustine, Florida. The prisoners had been captured in the Indian Territory at the close of the Red River War. At Fort Marion, Pratt immediately set about improving physical conditions for the Indians. He soon set up an Indian self-guarding system and worked in other ways to help them preserve their dignity. The prisoners became the center of interest by influential northerners wintering at St. Augustine. They encouraged Pratt in his plans for education, and several participated as volunteer teachers. Some were teachers or had missionary backgrounds. Pratt believed language was critical and that it was easier for Indians to learn English, than for Americans to learn the great variety of Indian languages. He organized volunteers to teach the Indian prisoners language, religion and customs to prepare them for life after release. When the prisoners were freed in 1878, Pratt encouraged them to seek more education. Seventeen went to Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute, an historically black college established soon after the Civil War for freedmen. Others were educated at private colleges in New York state. All funds for their education were raised by private benefactors.

"Pratt's Fort Marion experiment was becoming influential. Distinguished visitors began to visit from all over the country. The U.S. Commissioner of education came to see firsthand what Pratt was doing, and so did the president of Amherst College. The well-known illustrator J. Wells Champney arrived to draw pictures of the Indians for Harper's Weekly. The Smithsonian Institution commmissioned Clark Mills, who produced the Andrew Jackson Sculpture in the District of Columbia's Lafayette Square, to make plaster casts of the prisoners."[13]

Pratt's Fort Marion and Hampton programs convinced him that "distant education" was the only way to totally assimilate the Indian. The Indian, he wrote, “is born a blank, like all the rest of us. Transfer the savage born infant to the surroundings of a civilization and he will grow to possess a civilized language and habit.” [14] “If all men are created equal, then why were blacks segregated in separate regiments and Indians segregated on separate tribal reservations? Why weren’t all men given equal opportunities and allowed to assume their rightful place in society? Race became a meaningless abstraction in his mind.” [15] Pratt believed an industrial school model similar to Hampton would be useful for educating and assimilating Native Americans, and that Native American children immersed in white culture would learn skills and customs to compete on equal terms with whites.

“Give me three hundred young Indians and a place in one of our best communities, and let me prove it! Carlisle Barracks in Pennsylvania, has been abandoned for a number of years. It is in the heart of fine agricultural country. The people are kindly disposed, and long free from the universal border prejudice against Indians.” This he later demonstrated by securing a petition in favor of the proposed school, signed by most of the leading citizens of Carlisle who stood solidly behind him for the next quarter of a century.[16]

Pratt and his supporters successfully lobbied Congress to establish the first model off-reservation boarding school for Native Americans in the United States at the historic Carlisle Barracks in Carlisle, Pennsylvania.[17]

Pratt founds Carlisle

On October 6, 1879, Captain Richard Henry Pratt offered Native Americans a path to opportunity and hope at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, when eighty-two boys and girls in native dress, tired and excited, arrived on the Eastern edge of Carlisle at midnight. Hundreds of people from Carlisle were waiting at the railroad station to walk with them to them to the ”Old Barracks.” [18] The Carlisle Indian School School formally opened on November 1, 1879, with an enrollment of 147 students. The youngest was six and the eldest twenty-five, but the majority of them were teenagers. Two-thirds were the children of Western tribal leaders. The first class was made up of eighty-four Lakota, fifty-two Cheyenne, Kiowa and Pawnee, and eleven Apache. The class included a group of students from Fort Marion who wanted to continue their education with Pratt at Carlisle.[19]

Pratt believed that Native Americans were the equals of whites, and founded Carlisle to immerse Native American children in white culture and teach them English, new skills and customs. The first Carlisle students were enrolled by leading Lakota chiefs. After the end of Great Sioux War in 1877, the Lakota people were depressed, impoverished, harassed and confined. At the time, many people believed Native Americans were a vanishing race whose only hope for survival was rapid cultural transformation. The U.S. government urgently sought a progressive educational model to rapidly assimilate Indians into white culture. Whether this could be achieved and how rapidly it could be done was unknown.[17] The Carlisle Barracks with its glamorous history appealed to Pratt’s master plan. He realized that Carlisle’s proximity to officials in Washington, D.C. was as important as its reservations in the West, and people could see firsthand their ability to learn and witness their progress.[20]

Discipline at Carlisle

The children who arrived at Carlisle able to speak some English were presented to the other children as translators. The authorities at the School sometimes used the children’s traditional respect for elders to require them to inform on other children’s misbehavior. This was typical of the pattern in the large families of the time, in which older children were required to take care of and discipline younger children. School officials required students to take new English names. This was confusing, as the names from which they were to choose had no meaning. Luther Standing Bear was one the first students to arrive when Carlisle opened its doors in 1879. Once there, he was asked to choose a name from a list on the wall. He randomly pointed at the symbols on a wall and named himself Luther, and his father's name became his surname.[21]

Luther reported: “The civilizing process began at Carlisle began with clothes. Whites believed the Indian children could not be civilized while wearing moccasins and blankets. Their hair was cut because in some mysterious way long hair stood in the path of our development. They were issued the clothes of white men. High collar stiff-bosomed shirts and suspenders fully three inches in width were uncomfortable. White leather boots caused actual suffering. Standing Bear later wrote that red flannel underwear caused "actual torture." He remembered the red flannel underwear as "the worst thing about life at Carlisle.” [22]

Discipline was strict and consistent, according to the military tradition, with a student ‘court-martial’ for serious cases. The discipline of boys was pretty severe, along army rules to a large extent, but organization into squads and companies appealed to the Indian students’ warrior traditions, and to win officers’ stripes they were willing to endure much. In most instances there was genuine affection between the Captain and the students.[23]

Children who could not adjust at Carlisle eventually returned to their families and homes. Several years after a student ran away, the young man approached Pratt in the lobby of a New York hotel. Well dressed, and wearing an air of modest confidence, he explained that he had found himself a good job, worked hard and saved some money. "Hurrah!"" the Captain exclaimed. "I wish all my boys would run away!" [24]

Student recruitment

In November 1878, Pratt was ordered by the War Department to report to the Secretary of the Interior for Indian educational duty and then proceed to Dakota Territory to recruit Sioux students for the new school. The Sioux were selected on the principle of taking the most pains with those who gave the most trouble.[25] The order came less than three years after the Sioux and their allies defeated Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer and the U.S. 7th Cavalry Regiment in the Battle of the Little Big Horn. Pratt protested that he was not familiar with the Sioux and they were in a hostile attitude toward the U.S. Government. But the War Department was insistent that Pratt go to Red Cloud and Spotted Tail, important Sioux Chiefs, because some military strategists believed their children would be hostages for the good behavior of their people.[26] Pratt’s speech to Brulé Lakota Chief Spotted Tail convinced him to send his children to Carlisle.

“Spotted Tail, you are a remarkable man. Your name has gone all over the United States. It has even gone across the great water. You are such an able man that you are the principal chief of these thousands of your people. But Spotted Tail, you cannot read or write. ou claim that the government has tricked your people and placed the lines of your reservation a long way inside of where it was agreed that they should be. You put your cross-mark signature on the treaty which fixed the lines of your reservation. That treaty says you agreed that the lines of your reservation should be just where these young men now out surveying are putting posts and markers. You signed that paper, knowing only what the interpreter told you it said. If anything happened when the paper was being made up that changed its order, if you had been educated and could read and write, you could have known about it and refused to put your name on it. Do you intend to let your children remain in the same condition of ignorance in which you have lived, which will compel them always to meet the whiter man at a great disadvantage through an interpreter, as you have to do? Cannot you see that but is far, far better for you to have your children educated and trained as our children are so that they can speak the English language, write letters and do the things which bring to the white man such prosperity. As your friend, Spotted Tail, I urge you to send your children with me to this Carlisle School and I will do everything I can to advance them in intelligence and industry in order that they may come back and help you. Spotted Tail, I hear that you have a dozen children. Give me four or five, and let me take them back to Carlisle and show you what the right kind of education will do.[27]

In 1879, Oglala Lakota Chiefs Blue Horse, American Horse and Red Shirt enrolled their children in the first class at Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. They wanted their children to learn English, trade skills and white customs. "Those first Sioux children who came to Carlisle could not have been happy there. But it was their only chance for a future." [28] Pratt persuaded tribal elders and chiefs that the reason the Washichu (Lakota word for white man) had been able to take their land was because the Indians were uneducated. He believed that the Natives were disadvantaged by being unable to speak and write English and that if they had the knowledge, they may have been able to protect themselves. [ [File:Noted Indian Chiefs who visited Carlisle Indian School.png|thumb|John Nicolas Choate was the first and best known photographer of the Carlisle Indian School, and created a photographic record of the model school for documentation and publicity. "Noted Indian Chiefs who have visited the Indian Training School, Carlisle, Pa.", John Nicolas Choate. Carlisle, c. 1881]]

Luther Standing Bear was taught to be brave and unafraid to die, and left the reservation to attend Carlisle and do some brave deed to bring honor to his family. Standing Bear’s father celebrated his son’s brave act by inviting his friends to a gathering and gave away seven horses and all the goods in his dry goods store.[29] Luther became a school recruiter for Captain Pratt and periodically visited reservations. He was sincere in his desire to show what we had learned, and persuaded parents to send their children to Carlisle by his appearance, language and skills. However, many children died from infectious diseases in boarding schools and parents were fearful to let them go. Moreover, many parents were treated unfairly and had not been notified until after the children died and were buried. It was not the negligence of Captain Pratt, but rather lax Indian agents who would set aside letters from Carlisle until the parents came into the agency for something. While many parents were proud of Luther, they were afraid to send their children away fearing they would never see them again.[30]

No children were brought to Carlisle without the consent of their parents,[31] and consent was not gained without concessions. One was the promise to allow tribal leaders inspect the school soon after it opened. The first group of inspectors, some forty Sioux chiefs representing nine Missouri River agencies, visited Carlisle in June, 1880. Others tribal leaders followed. Before tribal delegations returned home, they usually spent a few days in Washington where they received the plaudits of government officials for allowing their children to participate in the Carlisle experiment.[32]

American Horse

Oglala Lakota Chief American Horse was one of the earliest advocates of education for Native Americans. While recruiting at Pine Ridge Reservation, Captain Pratt met heavy opposition from Red Cloud who was distrustful of white education, and who had no school age children. But Pratt couldn’t help noticing that American Horse “took a lively interest” in what he had to say. American Horse had grown into a influential tribal politician and was the head of a large household with two wives and at least ten children. He had become a sophisticated man who adroitly negotiated his way between the traditional Lakota society and the new white society encircling him. He had become a shrewd politician and his friendliness with whites was a calculation to win concessions for himself and his people. Above all, American Horse prided himself in his sagacity, It was glaring apparent to him that his offspring would have to deal with whites, and perhaps even live with them, whether they liked it or not. American Horse agreed to send two sons and a daughter for first class: Ben American Horse, Samuel American Horse and Maggie Stands Looking.[33] Native American historian Charles A. Eastman recalled, “His daughters were the handsomest Indian girls of full blood that I ever saw.” [34]

Model U.S. Indian Boarding School

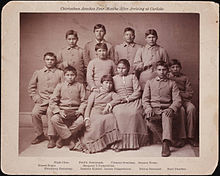

Pratt was so successful in his correspondence and methods that many Western chiefs suffering from cold and hunger on their reservations, begged him to bring more children East. The chiefs also wrote to Washington with a request to educate more of their children.[35] News of the educational experiment spread rapidly and many came to Carlisle to volunteer services and professional talents.[35] Pratt developed a photographic record of the school for publicity and documentation. The institution and the school were photographed during the school’s existence by approximately a dozen professional photographers. The first and best known photographer of the Carlisle Indian School was John Nicolas Choate.[36] ”After replacing Indian dress with military uniforms and cutting their hair in Anglo fashion, the Indians’ physical appearance was transformed. Pratt, in an effort to convince doubters of his beliefs, hired photographers to present this evidence. Before and after “contrast” photos were sent to officials in Washington, friends of the new school, and back to reservations to recruit new students.[37]

The minimum age for students was fourteen, and all students were required to be at least one-fourth Indian. The Carlisle term was five years, and the consent forms which the parents signed before the agent so stated. Pratt refused to return pupils earlier unless they were ill, unsuitable mentally or a menace to others.[38]

Between 1899 and 1904, Carlisle issued thirty to forty-five degrees as year. In 1905, a survey of 296 Carlisle graduates showed that 124 had entered government service, and 47 were employed off the reservations.[39] Anniversary and other school events were magnets for persons of distinction. Senators, Indian commissioners, secretaries of the Interior, college presidents and noted clergymen were accustomed to present the diplomas or address the graduating class upon these occasions. The gymnasium held 3,000 persons and was generally filled with an audience of townspeople and distinguished visitors showing their support for aspiring Carlisle students.[40]

Carlisle, Pennsylvania

In 1880, Carlisle, Pennsylvania, was a thriving Eastern town, with a population of 6,209 people. The shoe factory in town employed over 800 residents. There were two railroads, three banks and ten hotels in Carlisle by the time Pratt established his school. By the late nineteenth century, there were 1,117 "colored residents" in Carlisle. Carlisle boasted a low unemployment rate and a high literacy rate at the time of the census. Carlisle was an ideal location for the Indian School for a number of reasons. Firstly, it was far enough inland from the east coast so that the Indians would not be overwhelmed with urban life. However, it was not so far west that the students would be able to run away back to their families. The historic Carlisle Barracks were vacant, making the town an ideal location for Pratt's school, and less than two miles from an already well established institution, Dickinson College. The citizens of Carlisle embraced the Carlisle Indian School for thirty-nine years. When the first Indian School students arrived in Carlisle on October 6, 1879, they were in tribal dress. “For the people of Carlisle it was a gala day and a great crowd gathered around the railroad. The older Indian boys sang songs aloud in order to keep their spirits up and remain courageous, even though they were frightened." [41] "For years, it was a common event for the people of Carlisle to greet the Carlisle Indian football victors on their homecoming. Led by the Indian School Band, the Carlisle Indians paraded in their nightshirts down the streets of Carlisle and on to the school on the edge of town." [42] Residents of Carlisle stood on their doorsteps and cheered as the Carlisle Band led a snake dance from one end of town to the other.[43]

Dickinson College

Carlisle was also home to Dickinson College, less than two miles from the Carlisle Indian School, America's 16th oldest college.[44] Dickinson College and the Carlisle Indian School collaboration began when Dr. James McCauley, President of Dickinson College, led the first worship service at the Indian School in 1879. It was Mrs. Pratt who had initiated the contact between the Indian School and Dickinson. Upon Pratt’s absence one Sunday, Mrs. Pratt wrote to President McCauley and requested his aid as a minister which he graciously accepted. The relationship did not stop there with Richard Pratt noting that, “from that time forward Dr. McCauley became an advisor and most valued friend to the school.".[45] The collaborative effort between Dickinson College and the Carlisle Indian School lasted almost four decades, from the opening day to the closing of the school. Dr. McCauley helped Pratt to develop a Board of Trustees and a Board of Visitors composed of different heads of leading national educational institutions and wealthy donors. Dickinson College professors served as chaplains and special faculty to the to the Indian School,[46] and college students volunteered services, observed teaching methods and participated in events.[47] Dickinson College also provided Carlisle Indian School students with access to the Dickinson Preparatory School ("Conway Hall") and college level education.[48] Thomas Marshall was one of the first Native American students at Dickinson. Carlisle is also home to the Dickinson School of Law, and in the early 1900s a few Carlisle Indian School graduates attended the law school: Albert A. Exendine, Ernst Robitaille, Hastings M. Robertson, Victor M. Kelley and William J. Gardner.

In 1889, Dr. George Edward Reed assumed the position of President of Dickinson College and continued the close relationship between the Indian School and Dickinson College through Pratt’s departure in 1904. Reed told an audience at the Indian School that “we who live in Carlisle, who come in constant contact with the Indian School, and who know of its work, have occasion to be agreeably surprised with the advance we are able to see." In June 1911, Reed addressed the one hundred and twenty-eighth commencement of Dickinson College, where he presented an Honorary Degree of Master of Arts to Pratt’s successor, Superintendent Moses Friedman, for his work at the Carlisle Indian School. [49]

Prof. Charles Francis Himes was a professor of natural science at Dickinson College for three decades and instrumental in expanding the science curriculum. Professor Hines took an interest in the Carlisle Indian School and his notable lectures on electricity (“Why Does It Burn”), "Lightning" and "Gunpowder" received a favorable reaction from parents and students. Himes lectured to Chiefs Red Cloud, Roman Nose and Yellow Tail, and brought Indian students to the Dickinson laboratory to give lectures. Himes also promoted Carlisle’s success in national academic circles.[50]

Luther Standing Bear recalled that one day an astronomer came to Carlisle and gave a talk. “The astronomer explained that there would be an eclipse of the moon the following Wednesday night at twelve o’clock. We did not believe it. When the moon eclipsed, we readily believed our teacher about geography and astronomy.”[51]

In addition to academic contact, the two institutes had contact in the public venue as well. The best known instances include the regular defeats of Dickinson College by the Carlisle Indian School football team and other athletic competitions.[52]

Education and curricula

Carlisle curricula included subjects such as English, math, history, drawing and composition. Students also learned trade and work skills such as farming and manufacturing. Older students used their skills to help build new classrooms and dormitories. Carlisle students produced a variety of weekly and monthly newspapers and other publications that were considered part of their "industrial training," or preparing for work in the larger economy. Marianne Moore was a teacher at Carlisle before she became one of America's leading poets.Music was a part of the program, and many students studied classical instruments. The Carlisle Indian Band earned an international reputation. Native American teachers eventually joined the faculty, such as Ho-Chunk artist Angel DeCora, taught students about Native American art and heritage and fought harsh assimilation methods. Students were instructed in Christianity and expected to attend a local church, but had their choice among those in town. Carlisle students were required to attend a daily service and two services on Sundays. Students were expected to participate in various extracurricular activities. In addition to the YMCA and King Daughter Circle, the girls could choose between the Mercer Literary Society and the Susan Longstreth Society. The boys had a choice of the Standard Literary Society or the Invincible Debating Society.[53]

A summer camp was established in the mountains at Pine Grove Furnace State Park, near a place called Tagg’s Run. Students lived in tents and picked berries, hunted and fished.[53] Luther Standing Bear recalled: “In 1881, after the school closed for the summer vacation, some of the boys and girls were placed out in farmers’ homes to work throughout the summer. Those who remained at school were sent to the mountains for a vacation trip. I was among the number. When we reached our camping place, we pitched out tents like soldiers all in a row. Captain Pratt brought along a lot of feathers and some sinew, and we made bows and arrows. Many white people came to visit the Indian camp, and seeing us shooting with the bow and arrow, they would put nickels and dimes in a slot of wood and set them up for us to shoot at. If we knocked the money from the stick, it was ours. We enjoyed this sport very much, as it brought a real home thrill to us.” [54]

Carlisle Summer Outing Program

The Carlisle Summer Outing Program arranged for students to work in homes as domestic servants or in farms or businesses during the summer. The program won praise from reformers and administrators alike and helped increase the public’s faith that Indians could be educated and assimilated. The program gave students opportunities to interact and live in the white world and found jobs for students during the summer months with middle-class farm families where they earned their first wages.[55] Many students worked in the homes and farms of Quaker families in eastern Pennsylvania and surrounding states.[56] Some were sent to farms in the Pennsylvania Dutch Country of Dauphin, Lancaster, and Lebanon counties and acquired what would be a life long Pennsylvania Dutch accent.[57]

Students were required to write home at least every month, and as often as they chose. Nearly all the students lovingly inquired after absent brothers and sisters, and many sent money home, ten or twenty dollars of their own earnings.[58]

Maggie Stands Looking, a daughter of Oglala Lakota Chief American Horse, was among the first wave of children brought from Rosebud and one of Captain Pratt’s model students. Maggie had difficulty adjusting to the demands of her new lifestyle at Carlisle, and once slapped Miss Hyde, the matron, when Hyde insisted that Maggie make her bed every day and keep her room clean. Instead of retaliating, Miss Hyde stood her ground and Maggie acquiesced. Like most of the Carlisle students, Maggie was enrolled in the Summer Outing Program. After her arrival to her country home, Maggie wrote a letter to Pratt. "Dear Captain Pratt: What shall I do? I have been here two weeks and I have not bathed. These folks have no bath place. Your school daughter, Maggie Stands Looking." Pratt advised her to do as he had done on the frontier and signed his letter - "Your friend and school father. R.H. Pratt." Maggie replied, "After filling a wash basin with water and rubbing myself well, have had a bath that made me feel as good as jumping into a river." [59]

The Outing Program continued throughout the Carlisle's history, and of the thousands who attended Carlisle for the first twenty-four years, a least half participated in the program.[56] Around 1909, Superintendent Friedman expanded the Outing Program by placing boys in manufacturing corporations such as Ford Motor Company.[60] Over sixty of the boys from Carlisle were subsequently hired and worked steadily for Ford.[61] During the later part of World War I, about forty had good jobs in the Hog Island, Philadelphia, shipyards.[61]

Student internships

In 1883, Luther Standing Bear was sent to Philadelphia to work as an intern for John Wanamaker. Wanamaker's was the first department store in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and one of the first department stores in the United States. Luther was was told by Pratt: “My boy you are going away from us to work for this school. Go and do your best. The majority of white people think the Indian is a lazy good-for-nothing. They think he can neither work nor learn anything; that he is very dirty. Now you are going to prove that the red man can learn and work as well as the white man. If John Wanamaker gives you he job of blacking his shoes, see that you make them shine. Then he will give you a better job. If you are put into the office to clean, don’t forget to sweep up under the chairs and in the corners. If you do this well, he will give you better work to do.” [62] While riding on street cars in Philadelphia, Luther did not care to listen to the vulgar language used by white boys on the way to work.[63] At the end of his internship, the entire Carlisle school students and faculty traveled to a large meeting hall in Philadelphia where Pratt and Wanamaker spoke. Luther was asked to come to the stage, and Wanamaker told the students that Luther had been promoted from one department to another every month getting better work and better money and in spite of the fact that he employed over one thousand people, he never promoted anyone as rapidly as Luther.[64]

The Carlisle Indian Band

The Carlisle Indian Band earned an international reputation under a talented Oneida musician, Dennison Wheelock, who became noted as its leader, composer and compiler of modified Native airs.[65] Many students studied classical musical instruments. The Carlisle Indian Band performed at world fairs, expositions and every at national presidential inaugural celebration until the school closed. Luther Standing Bear was a bugler for military calls and educated as a classical musician. On May 24, 1883, Luther Standing Bear led the Carlisle Indian band of brass instruments as the first band to cross the Brooklyn Bridge on its grand opening.[66]

From 1897 to 1899, Zitkala-Ša played violin with the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston. In 1899, she took a position at the Carlisle Indian School where she taught music to the children and conducted debates on the treatment of Native Americans. In 1900, Zitkala-Ša played violin at the Paris Exposition with the school's Carlisle Indian Band. In the same year, she began writing articles on Native American life which were published in such popular periodicals as Atlantic Monthly and Harper's Monthly. Also in 1900, Zitkala-Ša was sent by Captain Pratt back to the Yankton Reservation for the first time in several years to recruit students. She was greatly dismayed to find there that her mother's house in disrepair, her brother's family in poverty, and that white settlers were beginning to occupy the land promised to the Yankton Dakota by the Dawes Act of 1877.[67] Upon returning to Carlisle, she came into conflict with Pratt. She resented the rigid program of assimilation and argued that the curriculum did not encourage Native American children to aspire to anything beyond lives spent in menial labor.[68] In 1901 Zitkala-Ša was dismissed, likely for an article she had published in Harper's Monthly describing the profound loss of identity felt by a Native American boy after being given an assimilationist education at Carlisle. Concerned with her mother's advanced age and her family's struggles with poverty, she returned to the Yankton Reservation in 1901. Zitkala-Ša dedicated her life to Indian reform, voting rights and education.

Native American arts program

Francis E. Leupp, Commissioner of Indian Affairs from 1904-1909, had a strong influence over the Carlisle Indian School. Leupp encouraged promoting Indian culture by teaching native arts and craft.[69] In 1905, Leupp wrote for the Carlisle Arrow: "It seems to me that one of the errors good people fall into in dealing with the Indian is taking it for granted that their first duty is to make a white man out of him." "The Indian is a natural warrior, a natural logician, a natural artist. We have room for all three in our highly organized social system. Let us not make the mistake, in the process, of absorbing them, of washing out of them whatever is distinctly Indian." [70]

In 1906, Leupp appointed Native American artist Angel De Cora, trained at Hampton and Smith College, instructor of the the first native arts course at the Carlisle Indian School. De Cora agreed to accept the position at Carlisle only if she "shall not be expected to teach in the white man's way, but shall be given complete liberty to develop the art of my own race and to apply this, as far as possible, to various forms of art, industries and crafts." [71] The project was ambitious, and in 1907 students constructed the Leupp Indian Art Studio. The studio was strategically positioned to the entrance to the campus and designed as an exhibition hall and artist studio. Materials were purchased by using profits from the prior Carlisle Indians football season. At the time, there was a growing appreciation and demand for Native American arts and crafts, and proceeds from sales were used to raise funds for individuals on reservations and to cultivate public interest in Indian crafts. Students enjoyed Plains art and drawing traditional pictographs on paper and slates.[72] The studio was a vibrant collection of paintings, drawings, leather work, bead work, jewelry and basketry made by students, and some produced on reservations. The floor was covered with colorful Navajo style blankets.[73] As head of the Leupp Art Studio from 1906 to 1915, De Cora emphasized design, and encouraged students to apply traditional tribal designs to marketable modern art media such as book plates, textiles and wallpaper. A photography gallery was operated at the Studio to afford an opportunity for the study of photography. Students were taught theory as well as practice of the art, i.e. developing, toning, printing, mounting and retouching.[74] The native arts program at Carlisle reflected the first governmental recognition of the value of Native American arts curricula in a U.S. Indian School.[75]

In 1908, De Cora married a Carlisle student Lone Star Dietz. At the age of 23, Dietz enrolled at Carlisle where he studied art in Philadelphia in the Summer Outing Program. After his marriage to De Cora. he continued in the roles of student and assistant art teacher. In 1909, the school launched a monthly literary magazine known as the Indian Craftsman, later changed to The Red Man. Designed by the school’s art department, printed and, in part written by students, the magazine gained a wide reputation for the quality of its appearance and content. Lone Star created cover designs for almost all of the fifty issues of the magazine between 1909 and 1914. During their time at Carlisle, Angel and Lone Star Dietz brought cultural awareness to students through innovative teaching programs. During her nine years at Carlisle, De Cora helped students understand and integrate their past and present experiences.[76]

Progressive Era fight for the image of Native Americans

From 1886 to the onset of World War I, Progressive Reformists fought a war of images with Wild West shows before the American public at world fairs, expositions and parades.[77] Pratt and other reformist progressives led an unsuccessful campaign to discourage Native Americans from joining Wild West shows. Reformist Progressives vigorously opposed to theatrical portrayals of Native Americans in popular Wild West shows and believed Wild West shows portrayed Native Americans as savages and vulgar stereotypes. Reformist progressives also believed Wild West shows exploited and demoralized Native Americans. Other Progressives, such as “Buffalo Bill” Cody, who as Pratt believed Indians equals as whites, had a different approach. He allowed Indians to be Indians. New ideas were not to be thrust forcefully upon Native peoples. Cody believed Native Americans would observe modern life and different cultures, acquire new skills and customs, and change at their own pace and terms. Both Pratt and Cody offered paths of opportunity and hope during time when people believed Native Americans were a vanishing race whose only hope for survival was rapid cultural transformation.[78] Notwithstanding his criticisms, Pratt invited his old friend Buffalo Bill Cody and his Wild West show to perform in Carlisle on June 24, 1898. The school paper Red Man reported that students were "privileged to witness the best exhibition of some rude manners and customs of the people of the western frontier in the fifties and sixties." [79]

During the Progressive Era of the late 19th and early 20th century, there was an explosion of public interest in Native American culture and imagery. Newspapers, dime-store novels, Wild West shows and public exhibitions portrayed Native Americans as a “Vanishing Race.” American and European anthropologists, historians, linguists, journalists, photographers, portraitists and early movie-makers believed time was of the essence to study western Native American peoples. Many researchers and artists lived on government reservations for extended periods to study Native Americans before they “vanished.” Their inspired effort heralded the “Golden Age of the Wild West.” Photographers included Gertrude Käsebier, Frank A. Rinehart, Edward Curtis, Jo Mora and John Nicholas Choate, while portraitists included Elbridge Ayer Burbank, Charles M. Russell and John Hauser. The “Vanishing Race” theme was dramatized at the Trans-Mississippi Exposition of 1898 at Omaha, Nebraska, and the the Pan-American Exposition of 1901 in Buffalo, New York. Exposition organizers assembled Wild Westers representing different tribes who portrayed Native Americans as a “vanishing race” at “The Last Great Congress of the Red Man”, brought together for the first and last time, apparently to commiserate before they all vanished.[80]

During this period, U.S. government policy focused upon acquiring Indian lands, restricting cultural and religious practices and sending Native American children to boarding schools. Progressives agreed that the situation was serious and that something needed to be done to educate and acculturate Native Americans to white society, but they differed as to education models and speed of assimilation. Reformist progressives, a coalition led by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Native American educators and Christian organizations, promoted rapid assimilation of children through off-reservation Indian boarding schools and immersion in white culture.[81]

At Carlisle, Pratt developed a photographic record of the model school for publicity and documentation. The institution and the school were photographed during the school’s existence by approximately a dozen professional photographers. The photographs evidenced that the school successfully acclimated Indians to the white man’s culture.[82] The first and best known photographer of the Carlisle Indian School was John Nicolas Choate.[83] ”After replacing Indian dress with military uniforms and cutting their hair in Anglo fashion, the Indians’ physical appearance was transformed." Before and after “contrast” photos were sent to officials in Washington, charitable donors and to reservations to recruit new students.[37] "Pratt's powerful photographs showing his quick results helped persuade Washington that he was doing vital work.[84]

Society of American Indians

The Carlisle Indian School was a well-spring for the Society of American Indians, the first Indian rights organization created by and for Indians. The Society was a group of about fifty prominent Native American intelligentsia who exchanged views collectively confronting their tribes and gave birth to Pan-Indianism.[85] The organization was influenced by the Carlisle experience and dedicated to self-determination and preserving Native American culture. From 1911 to 1923, the Society was forefront in the fight for Indian citizenship and the passage of the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924. Founding members included Dr. Carlos Montezuma, Dr. Charles Eastman, Angel De Cora, Zitkala-Ša and Chauncey Yellow Robe. The Society of American Indians printed a quarterly literary journal, American Indian Magazine. Dr. Montezuma joined Pratt at the Carlisle Indian School as a resident physician from 1895-1897. Montezuma a correspondent with Pratt since 1887, was drawn to the noble experiment at Carlisle. The physician Charles Eastman and his wife, Elaine Goodale Eastman, and children, resided at Carlisle in 1899, and were frequent visitors and lecturers.[86]

World fairs and expositions

During the Progressive Era, from the late 19th century until the onset of World War I, Native American performers were major draws and money-makers. Millions of visitors at world fairs, exhibitions and parades throughout the United States and Europe observed Native Americans portrayed as the vanishing race, exotic peoples and objects of modern comparative anthropology.[87] Reformists Progressives fought a war of words and images against popular Wild West shows at world fairs, expositions and parades.

In 1893, the fight for the image of the Native American began when Reformist Progressives pressured organizers to deny Buffalo Bill Cody a place at the Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago, Illinois.[88] Instead, a feature of the Exposition was a model Indian school and an ethnological Indian village supported by the Bureau of Indian Affairs.[89]

In style, Buffalo Bill established a fourteen-acre swath of land near the main entrance of the fair for "Buffalo Bill's Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World" where he erected stands around an arena large enough to seat eighteen thousand spectators. Seventy-four Wild Westers from Pine Ridge, South Dakota, who had recently returned from a tour of Europe, were contracted to perform in the show. Cody also brought in an additional one hundred Wild Westers directly from Pine Ridge, Standing Rock and Rosebud reservations, who visited the Exposition at his expense and participated in the opening ceremonies.[90] Over two million patrons saw Buffalo Bill’s Wild West outside the Columbian Exposition, often mistaking the show as an integral part to the World's Fair.[91] The Louisiana Purchase Exposition of 1904, known as the St. Louis World’s Fair, was the last of the great fairs in the United States before World War I. Organizers wanted their exotic people to be interpreted by anthropologists in a modern scientific manner portraying contrasting images of Native Americans.[92] A Congress of Indian Educators was convened and Oglala Lakota Chief Red Cloud and Chief Blue Horse, both eighty-three years old, and the best-known Native America orators at the St. Louis World's Fair, spoke to audiences. A model Indian School was placed on top on a hill so Indians below could see their future as portrayed by the Bureau of Indian Affairs.[93] On one side of the school, “blanket Indians”, men or women who refused to relinquish their native dress and customs, demonstrated their artistry inside the school on one side of the hall. On the other side, Indian boarding school students displayed their achievements in reading, writing, music, dancing, trades and arts.[94] The Carlisle Indian Band performed at the Pennsylvania state pavilion, and the Haskell Indian Band performed a mixture of classical, popular music and Dennison Wheelock’s “Aboriginal Suite” which included Native dances and war whoops by band members. [95]

The Inaugural Parade of President Theodore Roosevelt, 1905

On March 4, 1905, Wild Westers and Carlisle portrayed contrasting images of Native Americans at the First Inaugural Parade of President Theodore Roosevelt. Six famous Native American Chiefs, Geronimo (Apache), Quanah Parker (Comanche), Buckskin Charlie (Ute), American Horse (Sioux), Hollow Horn Bear (Sioux) and Little Plume (Blackfeet), met in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, for dress rehearsal on the main street to practice for the parade in Washington. [96]

Theodore Roosevelt sat in the presidential box with his wife, daughter and other distinguished guests, and watched West Point cadets and the famed 7th Cavalry, Gen. George A. Custer’s former unit that fought at the Battle of Little Bighorn, march down Pennsylvania Avenue. When the contingent of Wild Westers and the Carlisle Cadets and Band came into view, President Roosevelt vigorously waived his hat and all in the President’s box rose to their feet to behold the powerful imagery of the six famous Native American Chiefs on horseback adorned with face paint and elaborate feather headdresses, followed by the 46-piece Carlisle Indian School Band and a brigade of 350 Carlisle Cadets at arms. Leading the group was Geronimo, in full Apache regalia including war paint, sitting astride his horse, also in war paint, in the center of the street. It was reported that: “The Chiefs created a sensation, eclipsing the intended symbolism of a formation of 350 uniformed Carlisle students led by a marching band,” and “all eyes were on the six chiefs, the cadets received passing mention in the newspapers and nobody bothered to photograph them.” [97]

The Carlisle Indians

During the early 20th century, the Carlisle Indian School was a national football powerhouse, and regularly competed against other major programs such as the Ivy League schools Harvard, Pennsylvania, Cornell, Dartmouth, Yale, Princeton, Brown, and Army and Navy. Coach Pop Warner led a highly successful football team and athletic program at the Carlisle School, and went on to create other successful collegiate programs. He coached the exceptional athlete Jim Thorpe and his teammates, bringing national recognition to the small school. By 1907, the Carlisle Indians were the most dynamic team in college football. They had pioneered the forward pass, the overhand spiral and other trick plays that frustrated their opponents. The Carlisle Indians have been characterized as the “team that invented football.”[98]

In 1911, the Indians posted an 11–1 record, which included one of the greatest upsets in college football history. Legendary athlete Jim Thorpe and coach Pop Warner led the Carlisle Indians to a 18–15 upset of Harvard. Thorpe scored all of the Indians' points in a shocking upset over the period powerhouse, 18–15.[99] During the program's 25 years, the Carlisle Indians compiled a 167–88–13 record and winning percentage (.647) which makes it the most successful defunct major college football program. The Carlisle Indians developed a rivalry with Harvard and loved to sarcastically mimic the Harvard accent. Even players who could barely speak English would drawl the broad Harvard “a” as in the Boston accent is non-rhotic, typically pronounced "pahk the cah in Hahvad Yahd". Carlisle students labeled any excellent performance, whether on the field or in the classroom, as "Harvard style." [100]

On November 9, 1912, Carlisle was to meet the U.S. Military Academy in a game at West Point, New York, between two of the top teams in the country. Pop Warner spoke to his team: “Your fathers and your grandfathers,” Warner began, “are the ones who fought their fathers. These men playing against you today are soldiers. They are the Long Knives. You are Indians. Tonight, we will know if you are warriors.” That dramatic evening Carlisle routed Army 27-6. That game, played just 22 years after the last Army battle with the Sioux at Wounded Knee, not only featured Jim Thorpe, but nine future generals including a linebacker named Dwight D. Eisenhower.[101] "It was an exquisitely apt piece of national theater: a contest between Indians and soldiers." [102]

Many Carlisle Indians, such Frank Mount Pleasant, Gus Welch, Francis M. Cayou, Joe Guyon, Pete Calac, Bemus Pierce, Hawley Pierce, Frank Hudson, William Jennings Gardner, Martin Wheelock, Jimmy Johnson, Isaac Seneca, Artie Miller, Bill Newashe, Woodchuck Welmas, Ted St. Germaine, Bill Winneshiek and Albert Exendine became professional athletes, coaches, educators and community leaders.[103]

Carlisle Wild Westers

The Carlisle Indian School and Wild Westing were portals to education, opportunity and hope, and came at a time when the Lakota people were depressed, impoverished, harassed and confined. Wild Westers from Pine Ridge enrolled their children at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School from its beginning in 1879 until its closure in 1918. Known as “Show Indians”, Oglala Wild Westers referred to themselves as Oskate Wicasa or "Show Man", a title of great honor and respect.[104] Many Carlisle students, mostly Lakota, had parents, family and friends who were Wild Westers. Ben American Horse and Samuel American Horse, sons of Oglala Lakota Chief American from Pine Ridge Reservation, South Dakota, attended Carlisle and went Wild Westing with their father.[105] Often entire families worked together, and the tradition of the Wild Wester community is not unlike the tradition of circus families and communities.[106] Carlisle Wild Westers were attracted by the adventure, pay and opportunity and were hired as performers, chaperons, interpreters and recruiters.[105]

In 1902, Luther Standing Bear performed a solo dance, did war whoops and shook hands with King Edward VII, monarch of Great Britain, in London, England. The King had been very dignified and not even smiled, but when Luther got down to doing fancy steps and gave few Sioux yells, the King had to smile in spite of himself.[107]

Frank C. Goings, the recruiting agent for Buffalo Bill Cody and other Wild West shows at Pine Ridge, South Dakota, was a Carlisle Wild Wester with experience as a performer, interpreter and chaperon.[108] Goings carefully chose the famous chiefs, the best dancers, the best singers, and the best riders; screened for performers willing to be away from home for extended periods of time and coordinated travel, room and board.[109] He traveled with his wife and children, and for many years toured Europe and the United States with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, Miller Brothers 101 Ranch Real West and the Sells Floto Circus.[110]

Pratt’s Retirement

Pratt conflicted with government officials over his outspoken views on the need for Native Americans to assimilate. In 1904, Pratt denounced the Indian Bureau and the reservation system as a hindrance to the civilization and assimilation of Native Americans. "Better, far better for the Indians," he said, "had there never been a Bureau." As a result of the controversy, Pratt was forced to retire as superintendent of Carlisle after twenty-four years and was placed on the retired list as a brigadier general.[111] In retirement, Pratt and his wife Anna Laura traveled widely, often visiting former students and lecturing and writing on Indian issues.[112] Pratt continued to advocate for Native American rights until his death at the age of eighty-three on March 15, 1924, at the Letterman Army Hospital in the Presidio of San Francisco. Pratt's modest granite memorial stone in Arlington National Cemetery says “”Erected In Loving Memory by his Students and Other Indians.”[113]

Assimilation efforts at Carlisle

Carlisle was created with the explicit goal of assimilating Native Americans into mainstream European-American culture.[114] "The goal of acculturation was to be accomplished by “total immersion” in the white man’s world." [5] Pratt founded Carlisle to immerse Native American children in mainstream culture and teach them English, new skills, and customs. Pratt's slogan was "to civilize the Indian, get him into civilization. To keep him civilized, let him stay."[citation needed] Pratt’s approach was harsh but an alternative to the commonly-held goal of examination of Native Americans. A positive outcome of a Carlisle education was the student's increased multilingualism.[115]

During the first few weeks at Carlisle, when the Lakota and Dakota greatly outnumbered all other tribes, it was discovered that Cheyennes and Kiowas were learning to speak Lakota and Dakota. After that, English was the only language permitted on the campus. Dormitory rooms held three or four each, and no two students from the same tribe were permitted to room together. The plan helped in the rapid acquirement of English, and although some were hereditary foes, Pratt believed the Indian students to be less inclined to quarrel than most white children.[116] However, there were consequences. In 1879, Chief Blue Horse's son Baldwin Blue Horse, age 12, was in the first group of Oglala Lakota students to arrive at Carlisle. In 1888, Chief Blue Horse met with Baldwin at a performance of Buffalo Bill's Wild West in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Baldwin could not speak Lakota and Chief Blue Horse could not speak English, and an interpreter was called to enable them to converse.[117] One day, Luther Standing Bear was called to the superintendent’s office and asked him if it was a good idea to get some Indian boys from the reservation and put them in school with white boys, expecting that the Indian boys would learn faster by such an association. Luther agreed that it might be a good plan, so a permit was received from Washington. Sixty Indian boys from Pine Ridge were mixed with sixty white boys. They had hoped the Indians would learn the English language faster by this arrangement. “But lo and behold, the white boys began learning the Sioux language.” The program was discontinued.[118] Some Native Americans are angry about painful Indian boarding school experiences and Pratt’s Progressive Reformist views on assimilation have been condemned.[119]

Back on the reservation

Luther Standing Bear got mixed reception home on the reservation. Some were proud of his achievements while others did not like that he had become a white man. [120] He was happy to be home, and some of his relatives said that he “looked like a white boy dressed in eastern clothes.” Luther was proud to be compared to a white boy. But others would not shake his hand. Some returning Carlisle students were ashamed of their culture, while some even tried to pretend that they did not speak Lakota. The difficulties of returning Carlisle students disturbed white educators. Returning Carlisle students found themselves between two cultures not accepted by either. Some rejected their educational experiences and “returned to the blanket” casting off white ways, others found it more convenient and satisfying to remain in white society. Most adjusted to both worlds.[121]

In 1905, Standing Bear decided to leave the reservation. He was no longer willing to endure existence under the control of an overseer.[122] Luther sold his land allotment and bought a house in Sioux City, Iowa, where he worked as a clerk in a wholesale firm.[123] After a brief job doing rodeo performances with Miller Brothers 101 Ranch in Oklahoma, he moved to California to seek full time employment in the motion picture industry.[124] In later years, Luther reflected upon his decision to leave the reservation: “Sixteen years ago I left reservation life and my native people, the Oglala Sioux, because I was no longer willing to endure existence under the control of an overseer. For about the same number of years I had tried to live a peaceful and happy life; tried to adapt myself and make re-adjustments to fit the white man’s mode of existence. But I was unsuccessful. I developed into a chronic disturber. I was a bad Indian, and the agent and I never got along. I remained a hostile, even a savage, if you please. And I still am. I am incurable.” [125] While Standing Bear left the confinement of the reservation, he continued his serious responsibilities and as an Oglala Lakota chief, fighting to preserve Lakota heritage and sovereignty through public education.

Deaths from infectious diseases

Exposure to white men’s diseases, especially tuberculosis, was a major health problem on the reservation as well as the East. During the years of operation, hundreds of children died at Carlisle. Most died from infectious diseases common in the early 20th century that killed many children. More than 180 students were buried in the Carlisle Indian School Cemetery. The bodies of most who died were sent to their families. Children who died of tuberculosis were buried at the school, as people were worried about contagion.[126]

Carlisle's latter years

Beginning in the early 1900s, the Carlisle Indian School began to diminish in relevance. With growth of private and government reservation schools in the West, children no longer needed to travel to a distant Eastern school in Pennsylvania.[127] Successive superintendents at Carlisle Indian School after Pratt, Captain William A. Mercer (1904-1908), Moses Friedman (1908-1914), Oscar Lipps (1914-1917) and John Francis, Jr. (1917-1918), were besieged by faculty debate and pressures from the Indian Commission and the U.S. Army. Around 1913, rumors circulated at Carlisle that there was a movement to close the school. In 1914, a Congressional investigation focused on management at the school and the out-sized role of athletics. Pop Warner, Superintendent Moses Friedman and Bandmaster C.M. Stauffer were dismissed. After the hearings, attendance dwindled and morale declined. The reason for Carlisle’s existence had passed.[128] When the United States entered World War I on April 6, 1917, there was an additional reduction of enrollment. Many Carlisle alumni and students served in the U.S. military during World War I. On the morning of September 1, 1918, a transfer ceremony took place. The flag was lowered for the last time at the Carlisle Indian School and presented to Major A.C. Backmeyer, who raised it again over U.S. Army Base Hospital Number 31, a pioneering rehabilitation hospital to treat soldiers wounded in World War I.[129] Remaining students were sent home or to other off-reservation boarding schools in the United States.[130] In the spring of 1951, the U.S. Army War College, senior educational institution of the U.S. Army, relocated to Carlisle Barracks. In 1961, the complex was designated a National Historic Landmark (NHL).

US Army Heritage and Education Center

The U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center (USAHEC), in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, is the U.S. Army's primary historical research facility. Formed in 1999 and reorganized in 2013, the center consists of the U.S. Army Military History Institute (USAMHI), the Army Heritage Museum (AHM), the Digital Archives Division, the Historical Services Division, the Research and Education Services, and the USAHEC Staff. The U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center is part of the United States Army War College, but has its own 56-acre (230,000 m2) campus in Middlesex Township nearby Carlisle Barracks.

US Army War College Jim Thorpe Sports Day

Jim Thorpe Sports Days is the biggest annual extra-curricular event at the U.S. Army War College. Began in 1974, the competition in ten sports is among the military's senior service schools, the Army, Navy and Air Force Colleges.[131] The sports are played at Carlisle Barracks' historic Indian Field, where Jim Thorpe once displayed the teamwork, discipline and physical fitness that inspires the name of the athletic games at Carlisle.[132]

Carlisle Indian School Resource Center

The Carlisle Indian School is well remembered and honored by the people of Carlisle. The Carlisle Indian School Resource Center is a program of the Cumberland County Historical Society in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, housing an extensive collection of archival materials and photographs from the Carlisle Indian School. Among the items are 39 years of weekly and monthly school newspapers, musical and athletic programs, brochures, letters, catalogs and the annual reports to the Commissioners of Indian Affairs. The Resource Center has over 3,000 photographs and recorded oral histories from school alumni, relatives of former students and local townspeople. In 2000, the Cumberland County 250th Anniversary Committee worked with Native Americans from numerous tribes and non-natives to organize a Pow-wow on Memorial Day to commemorate the unique Carlisle Indian School, the students and their stories.[133]

21st-century Wild Westing and Powwows

Some Oglala Lakota people carry on family show business traditions from Carlisle alumni who worked for Buffalo Bill and other Wild West shows.[134] Americans and Europeans continue to have a great interest in Native peoples and enjoy powwows. Americans and Europeans continue to enjoy traditional Native Americans skills; horse culture, ceremonial dancing and cooking; and buying Native American art, music and crafts. There are several on-going national projects that celebrate Wild Westers and Wild Westing. Wild Westers still perform in movies, powwows, pageants and rodeos.

"Buffalo Bill's Wild West and the Progressive Image of American Indians" is a collaborative project of the Buffalo Bill Historical Center and the University of Nebraska-Lincoln Department of History with the assistance from the Center for Digital Research in the Humanities at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. This digital history project contains letters, official programs, newspaper reports, posters, and photographs. The project highlights the social and cultural forces at work at a particular moment that shaped how American Indians were defined, debated, contested, and controlled. This project emerged out of the Papers of William F. Cody project of the Buffalo Bill Historical Center.[135]

The National Museum of American History's Photographic History Collection at the Smithsonian Institution preserves and displays Gertrude Käsebier's photographs. Michelle Delaney has published “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Warriors: Photographs by Gertrude Käsebier".[136]

In media

- Band and Battalion of the U.S. Indian School is silent film documentary made on April 30, 1901 by American Mutoscope and Biograph Company made in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, USA. The cinematographer Arthur Marvin depicts a parade drill by the cadet corps of the American Indian School which includes many representatives of the Native American tribes in the United States.

- Carlisle Indian Industrial School was depicted in the 1951 movie classic Jim Thorpe. Thorpe thrived under the football tutelage of equally legendary football coach Glenn S. "Pop" Warner.[137]

- Part of the 2005 mini-series on Turner Network Television, Into the West, takes place at the school.

- The PBS documentary In the White Man's Image (1992) tells the story of Richard Pratt and the founding of the Carlisle School. It was directed by Christine Lesiak, and part of the series The American Experience.

- The Dear America Series young adult fictional diary, My Heart is on the Ground by Ann Rinaldi, tells the story of Nannie Little Rose, a Sioux girl sent to the school in 1880. (1999)

- Numerous additional works works address the stories of former residents of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School and other Native American boarding schools in Western New York and Canadian Indian residential school system, such as Thomas Indian School, Mohawk Institute Residential School (also known as Mohawk Manual Labour School and Mush Hole Indian Residential School) in Brantford, Southern Ontario, and Haudenosaunee boarding school; the impact of those and similar schools on their communities; and community efforts to overcome those impacts. Examples include: the film Unseen Tears: A Documentary on Boarding School Survivors,[138] Ronald James Douglas' graduate thesis titled Documenting ethnic cleansing in North America: Creating Unseen Tears,[139] and the Legacy of Hope Foundation's online media collection: "Where are the Children? Healing the Legacy of the Residential Schools".[140]

See also

Citations

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ "Carlisle Indian School". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Retrieved 2008-07-02.

- ^ Linda F. Witmer, “The Indian Industrial School: Carlisle, Pennsylvania 1879-1918, (hereinafter "Witmer") Cumberland County Historical Society (2002), cover.

- ^ Pratt, Richard Henry, "Battlefield and Classroom: Four Decades with the American Indian", (hereinafter "Pratt"), Robert M. Utely, ed, University of Oklahoma Press, (2004), p. xi-xv.

- ^ a b Witmer, cover.

- ^ The total number of students is listed as 10,595, with 1,842 list of names and nation unknown. Carlisle Indian School Tribal Enrollment Tally (1879-1918). http://home.epix.net/~landis/tally.html

- ^ Tom Benjey, “Doctors, Lawyers, Indian Chiefs”, (hereinafter "Benjey") (2008), p.6.

- ^ Witmer, p.xvi. Carlisle had developed something of a rivalry with Harvard, and though the Indians had never beaten the Crimson, they always gave them a game. The Indians both admired and resented the Crimson, in equal amounts. They loved to sarcastically mimic the Harvard accent; even players who could barely speak English would drawl the broad Harvard a. But Harvard was also the Indians' idea of collegiate perfection, and they labeled any excellent performance, whether on the field or in the classroom, as "Harvard style." Sally Jenkins, “The Real All Americans”, (hereinafter "Jenkins")(2007), p.198.

- ^ A cornerstone of Harvard, the first university in America, is Harvard Indian College. Harvard struggled financially soon after its 1636 inception. To support the faltering college, the English Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in New England (SPGNE) raised and granted funds for Indian education at Harvard. The College, in turn promised to waive tuition and provide housing for American Indian students. The founding Harvard Charter of 1650 manifests this promise and dedicates the institution to "the education of the English & Indian Youth of this Country in knowledge: and godliness." The Indian College’s founders hoped graduates would proselytize their home communities with the Gospel. http://www.peabody.harvard.edu/node/477 see Indian College http://www.fas.harvard.edu/~amciv/HistoryofIndianCollege.htm for history of the college

- ^ Witmer, p.xvi. Jenkins, p.198.

- ^ See Sally Jenkins, “The Real All Americans”, (2007), and Tom Benjey, “Doctors, Lawyers, Indian Chiefs”, (2008).

- ^ Benjey, p.6.

- ^ Jenkins, p. 57.

- ^ Witmer, p.11.

- ^ Witmer, p.3. Pratt, p.6-8.

- ^ Elaine Goodale Eastman, “Pratt: The Red Man’s Moses”,(hereinafter "Eastman"), (1935), p.77.

- ^ a b Pratt, p. xi-xvi.

- ^ Witmer, p.17.

- ^ Bell, "Telling Stories Out of School," Ph.D. dissertation, Stanford University, 1998, cited in Witmer, p.75, 323 n. 31.

- ^ Witmer, p.12-13.

- ^ Luther Standing Bear, p.133.

- ^ Luther Standing Bear, “Land of the Spotted Eagle”, (1933), p.232-233.

- ^ Eastman, p. 209. Witmer, p. 23.

- ^ Eastman, p,232.

- ^ Witmer, p.10.

- ^ Witmer, p.13.

- ^ Pratt, p.222-224.

- ^ Ann Rinaldi, “My Heart is on the Ground: the Diary of Nannie Little Rose, a Sioux Girl, Carlisle Indian School, Pennsylvania, 1880,” (1999), p. 177.

- ^ Joseph Agonito, “Lakota Portraits: Lives of the Legendary Plains People” (hereinafter “Agonito”)(2011), p.237.

- ^ Luther Standing Bear, "My People the Sioux", (hereinafter "Luther Standing Bear"), (1928), p.162-163.

- ^ Witmer, p. 16.

- ^ Herman J. Viola, "Diplomats in Buckskins: A History of Indian Delegations to Washington", (1981), p.50, citing "Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs for 1880", p.viii.

- ^ Witmer, p.15.

- ^ Eastman, p.178.

- ^ a b Witmer, p.25.

- ^ Witmer, p.115.

- ^ a b Witmer, p.24.

- ^ Eastman, p.216.

- ^ Jenkins p. 216.

- ^ Eastman, p. 219.

- ^ Nancy Van Dolsen. "Carlisle 1880: A Historical Demographical Approach." Honors History diss., Dickinson College, 1982.

- ^ Witmer, p.47.

- ^ Jenkins, p.238.

- ^ Dickinson College was chartered September 9, 1783, five days after the signing of the Treaty of Paris, making it the first college to be founded in the newly recognized United States and founded by Benjamin Rush, a signer of the United States Declaration of Independence and originally named "John and Mary's College" in honor of a signer of the United States Constitution.

- ^ Pratt noted that, “We had the advantage of contacting and contending with our distinguished neighbor, Dickinson College, with its more than a century of success in developing strong and eminent men to fill the highest places in our national life." Pratt, 316.

- ^ Dr. James Andrew McCauley, Professor Charles Francis Himes, Dr. George Edward Reed, Stephen Baird and Joshua Lippincott fostered the relationship between the institutions through religious services, advisory meetings, lectures and commencement speeches. http://wiki.dickinson.edu/index.php?title=Influence_from_the_Faculty_at_Dickinson&action=edit

- ^ The presence of Native Americans on campus generated great interest among Dickinson students. Dickinson students enjoyed visiting the Indian School to offer their talents and services. Indeed, the October 24, 1896 Dickinsonian "On the Campus" section tells of the new volunteer Sunday School teachers from the college chapter of the YMCA. It further declares that those who have Indian boys “enjoy a rare privilege. The work is doubly interesting because one can be studying the characteristics of his scholars, at the same time learning many valuable lessons in methods of teaching.” In addition, at the time of the Indian School commencement, it was traditional for a half day holiday to be given so Dickinson students could attend the “very interesting exercises.”

- ^ http://wiki.dickinson.edu/index.php/History_of_Conway_Hall

- ^ The Indian Craftsman, “Address by Dr. Geo. E. Reed; President of Dickinson College,” May 1909, vol. 1 no. 4 (Carlisle: The Carlisle Indian Press, 1909; reprint. New York: Johnson Reprint Corporation, 1971), 19. The Red Man. “Address by George Edward Reed.” May 1913, vol. 5 no. 9 (Carlisle: The Carlisle Indian Press, 1913; reprint. New York: Johnson Reprint Corporation, 1971), 400.

- ^ Charles Francis Himes, The White Man’s Way; Illustrated Talks on Scientific Subjects to “Indian Chiefs” on their Visits to the Carlisle Indian School. Read before the Historical Section of the Hamilton Library Association, Carlisle, Pa. (Carlisle: Hamilton Library Association, 1916), 14. See http://archives.dickinson.edu/people/charles-francis-himes-1838-1918. Jenkins, p. 80-81.

- ^ Luther Standing Bear, p. 155.

- ^ Jacqueline Fear-Segal, “Nineteenth-Century Indian Education: Universalism Versus Evolutionism,” Journal of American Studies 33 (1999): 330. Richard Henry Pratt, The Indian Industrial School, Carlisle Pennsylvania, (PA: Cumberland County Historical Society, 1979): 30. Carmelita A. Ryan, “The Carlisle Indian Industrial School” (Thesis, Georgetown University, 1962), 67.

- ^ a b Witmer, p.29.

- ^ Luther Standing Bear, p.154-155.

- ^ Luther Standing Bear, p. v. The program worked in the East, but not the West.

- ^ a b Witmer, p.37.

- ^ Benjey, p.21.

- ^ Eastman, p.225.

- ^ Barbara Landis, “Carlisle Indian Industrial School History” at http://home.epix.net/~landis/histry.html. Pratt, p. 275-276.

- ^ Witmer, p.76.

- ^ a b Eastman, p.241.

- ^ Luther Standing Bear, p. 178.

- ^ Luther Standing Bear, p. 182.

- ^ Luther Standing Bear, p. 184.

- ^ Eastman, p. 212.

- ^ Luther Standing Bear, p. 149.

- ^ Capaldi, Gina (2011). Red Bird Sings: The Story of Zitkala-Sa, Native America Author, Musician, and Activist. Millbrook Press. p. 22. ISBN 0-7613-5257-0.

- ^ Rappaport, Helen (2001). Encyclopedia of Women Social Reformers Volume 1. ABC-CLIO. p. 100. ISBN 1-57607-101-4.

- ^ Witmer, p.77.

- ^ http://home.epix.net/~landis/decora.html

- ^ Witmer, p.78-79.

- ^ Witmer, p.31.

- ^ Jane E. Simonsen, Making Home Work: Domesticity and Native American Assimilation, (2006 ), p.203-208. See Suzanne Alene Shope, “American Indian Artist Angel Decora: Aesthetics, Power and Transcultural Pedagogy in the Progressive Era”, (2009), http://etd.lib.umt.edu/theses/available/etd-10132009-112300/unrestricted/Shope_umt_0136D_10058.pdf. More on Francis E. Leupp at http://home.epix.net/~landis/decora.html.

- ^ Witmer, p.120.

- ^ Witmer, p.80.

- ^ Witmer, p.78-80.

- ^ "It was one thing to portray docile natives who had not progressed much since the late fifteenth century, but quite another matter to portray some of them as armed and dangerous.” L.G. Moses, “Wild West Shows and the Images of American Indians, 1883-1933, (hereinafter “Wild West Shows and Images”) (1996), p.133. Indian Commissioner John H. Oberly explained in 1889: "The effect of traveling all over the country among, and associated with, the class of people usually accompanying shows, circuses and exhibitions, attended by all the immoral and unchristianizing surroundings incident to such a life, is not only most demoralizing to the present and future welfare of the Indian, but it creates a roaming and unsettled disposition and educates him in a manner entirely foreign and antagonistic to that which has been and now is the policy of the Government. “Wild West Shows and Images”, p.69.

- ^ Heppler, “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and the Progressive Image of American Indians”.http://segonku.unl.edu/~jheppler/showindian/analysis/show-indians/standing-bear/

- ^ Joel Phister, "Individually Incorporated Indians and the Multicultural Modern", (2004), p.72.

- ^ Nancy J. Parezo and Don D. Fowler, “The 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition: Anthropology Goes to the Fair”, (hereinafter "Parezo and Fowler"), (2007), p.6.

- ^ Jason A. Heppler, “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and the Progressive Image of American Indians”, 2011. Buffalo Bill's Wild West and the Progressive Image of American Indians is a collaborative project of the Buffalo Bill Historical Center and the University of Nebraska-Lincoln Department of History with the assistance from the Center for Digital Research in the Humanities at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

- ^ Witmer, p.113.

- ^ Witmer, p.115. See Laura Turner,"John Nicholas Choate and the Production of Photography at the Carlisle Indian School" at http://chronicles.dickinson.edu/studentwork/indian/4_choate.htm

- ^ Jenkins, p.82

- ^ Jenkins. p.276

- ^ http://home.epix.net/~landis/eastman.html

- ^ David R.M. Beck, “The Myth of the Vanishing Race”, Associate Professor, Native American Studies, University of Montana, February, 200. “Wild West Shows and Images”, p.131, 140.

- ^ “Wild West Shows and Images”, p.131, 140.

- ^ Financial difficulties, however, led the Bureau of Indian Affairs to withdraw its sponsorship and left the ethnological Indian Villages exhibit under the directorship of Frederick W. Putnam of Harvard's Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology. Robert A. Trennert, Jr., "Selling Indian Education at World's Fairs and Expositions, 1893-1904), American Indian Quarterly, (1987).

- ^ L. G. Moses, "Indians on the Midway: Wild West Shows and the Indian Bureau at World's Fairs", 1893-1904", South Dakota Historical Society, (1991), p. 210-215.

- ^ Parezo and Fowler, p.6. “Wild West Shows and Images”, p.137-138.

- ^ Indians performing included Oglala Lakotas from Pine Ridge Reservation with Cummins’s Wild West Show and Brulé Lakotas from Rosebud Reservation with the Deportment of Anthropology. Parezo and Fowler, p.131.

- ^ Parezo and Fowler, p.134.