Music video

A music video (also promo) is a short film or video that accompanies a complete piece of music, most commonly a song. Modern music videos were primarily made and used as a marketing device intended to promote the sale of music recordings. Although the origins of music videos go back much further, they came into their own in the 1980s, when Music Television's format was based around them.

Music videos can accommodate all styles of filmmaking, including animation, live action films, documentaries, and non-narrative, abstract film.

History of music videos

Early precedents

In 1910 Alexander Scriabin wrote his symphony Prometheus -- Poem of Fire for orchestra and "light organ". And as far back as the 1920s, the animated films of Oskar Fischinger (aptly labelled "visual music") were supplied with orchestral scores. Fischinger also made short animated films to advertise Electrola Records' new releases, making these films possibly the first music videos.

In 1929 the Russian film revolutionary Dziga Vertov made a 40 minute film called Man with the Movie Camera. It was an experiment on filming real, actual events, contrary to Georges Méliès theatrical approach. The film is entirely backed by music (played live by an orchestra on theaters) and has no dialogue at all. It's notable for the use of fast editing and fast frame frequencies, which were all synched to the music in order to create an emotion on the viewer. The film is highly regarded for setting the principles of the documentary genre, but it is also important in all filmmaking.

Sergei Eisenstein's 1938 film Alexander Nevsky, which features extended scenes of battles choreographed to a score by Sergei Prokofiev, was influenced by Vertov's work and it set new standards for the use of music in film and has been described as the first music video.

Animation pioneer Max Fleischer introduced a series of sing-along short cartoons called Screen Songs, which invited audiences to sing along to popular songs by "following the bouncing ball". Early 1930s entries in the series featured popular musicians performing their hit songs on-camera in live-action segments during the cartoons.

The early animated efforts of Walt Disney, his Silly Symphonies, were built around music. The Warner Brothers cartoons, even today billed as Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies, were initially fashioned around specific songs from upcoming Warner Brothers musical films. Live action musical shorts, featuring such popular performers as Cab Calloway, were also distributed to theatres.

Blues singer Bessie Smith appeared in a two-reel short film called Saint Louis Blues (1929) featuring a dramatized performance of the hit song. It was shown in theatres until 1932. Numerous other musicians appeared in short musical subjects during this period. Later, in the mid-1940s, musician Louis Jordan made short films for his songs, some of which were spliced together into a bizarre feature film Lookout; these films were, according to music historian Donald Clarke, the ancestors of music videos [1].

Another early form of music video were one-song films called "Soundies" made in the 1940s for the Panoram visual jukebox. These were short films of musical selections, usually just a band on a movie-set bandstand, made for playing. Thousands of Soundies were made, mostly of jazz musicians, but also torch singers, comedians, and dancers.

Before the Soundie, even dramatic movies typically had a musical interval, but the Soundie made the music the star and virtually all the name jazz performers appeared in Soundie shorts, many still available on compilation video tapes or DVDs.

The Panoram jukebox with eight three-minute Soundies were popular in taverns and night spots, but the fad faded during World War II.

In 1940, Walt Disney released Fantasia, an animated film based around famous pieces of classical music.

Film and video promos

In 1956 Tony Bennett was filmed walking along The Serpentine in Hyde Park, London as his recording of "Stranger in Paradise" played; this film was distributed to and played by UK and US television stations, leading Bennett to later claim he made the first music video.

In 1961 Ozzie Nelson directed and edited the video of "Travelin' Man" by his son Ricky Nelson. It featured images of various parts of the world mentioned in the Jerry Fuller song and Ricky singing. It is believed to be the very first rock video.

The pioneering full-colour music video for The Exciters' "Tell Him" from 1962 greatly influenced all that came afterwards.

The defining work in the development of the modern music video was The Beatles' first major motion picture, A Hard Day's Night in 1964, directed by Richard Lester. The musical segments in this film arguably set out the basic visual vocabulary of today's music videos, influencing a vast number of contemporary musicians, and countless subsequent pop and rock group music videos.

That same year, The Beatles began filming short promotional films for their songs which were distributed for broadcast on television variety shows in other countries, primarily the U.S.A. (At the same time, The Byrds began using the same strategy to promote their singles in the United Kingdom, starting with the 1965 single "Set You Free This Time".) By the time The Beatles stopped touring in late 1966 their promotional films, like their recordings, were becoming increasingly sophisticated, and they now used these films to, in effect, tour for them.

Also in 1966 the clip of Bob Dylan performing Subterranean Homesick Blues filmed by D A Pennebaker was much used. The clip's ironic portrayal of a performance and the seemingly random inclusion of a celebrity (Allen Ginsberg) in a non-performing role also became mainstays of the form. The clip has been much imitated.

Although unashamedly based on A Hard Day's Night, the hugely popular American TV series The Monkees was another important influence on the development of the music video genre, with each episode including a number of specially-made film segments that were created to accompany the various Monkees songs used in the series. The series ran from 1966 to 1968.

The Beatles took the genre to new heights with their groundbreaking films for "Strawberry Fields Forever" and "Penny Lane", made in early 1967, which used techniques borrowed from underground and avant garde film, such as reversed film effects, dramatic lighting, unusual camera angles and rhythmic editing. Created at the height of the psychedelic music period, these two landmark films are among the very first purpose-made concept videos that attempt to "illustrate" the song in an artful manner, rather than just creating a film of an idealized performance.

Other pioneering music videos made during this time include the promotional films made by The Doors. The group had a strong interest in film, since both lead singer Jim Morrison and keyboard player Ray Manzarek had met while studying film at UCLA. The clip for their debut single "Break On Through" is essentially structured as a filmed performance, but it is notable for its accomplished and atmospheric lighting, camera work and editing. The Doors also directed a superb promotional clip for their controversial 1968 anti-war single "The Unknown Soldier", in which the group stage a mock execution by firing squad. One of the clip's most innovative features is its use of external visuals sources, with extensive intercutting of archival footage and shocking contemporary TV footage of the carnage of the Vietnam War.

When released in 1968, the animated film Yellow Submarine was an international sensation, although The Beatles themselves had only a tangential involvement with it. Soon it was commonplace for artists to make promotional films, and bands like The Byrds and The Beach Boys were also making promotional films. Although these "film clips" were often aired on pop music TV shows, they were still considered as secondary at that time, with live or mimed performances generally given precedence.

The promotional clip continued to grow in importance, with television programs such as The Midnight Special and Don Kirshner's Rock Concert mixing concert footage with clips incorporating camera tricks, special effects, and dramatizations of song lyrics.

Other important contributions to the development of the genre include the film of the Woodstock Festival, and the various concert films that were made during the early Seventies, most notably Joe Cocker's Mad Dogs And Englishmen and particularly Pink Floyd's groundbreaking Live At Pompeii concert film, which featured sophisticated rhythmic cross-cutting.

Many countries with local pop music industries soon copied the trend towards music videos. In Australia promotional films by Australian pop performers were being made on a regular basis by 1966; among the earliest known are clips by Australian groups The Masters Apprentices and The Loved Ones.

Surf film makers such as Bruce Brown, George Greenough and Alby Falzon also made important contributions in their films, which featured innovative combinations of images and music, and they notably dispensed with all narration and dialogue for many extended surfing sequences in their films, presenting the surfing action accompanied by suitably atmospheric music tracks.

Alby Falzon's 1972 film Morning Of The Earth included a spectacular sequence (filmed by Greenough) that was constructed around the extended Pink Floyd track "Echoes". The group reportedly agreed to allow Falzon to use the music gratis, in exchange for a copy of Greenough's footage, which they used during their concerts for several years.

Other notable Australian developments in this field are the early 1970s monochrome promotional films made by Australian musician and filmmaker Chris Lofven, whose clips for the Spectrum song "I'll Be Gone" and the Daddy Cool song "Eagle Rock" were among the best of the early Australian music video productions. It is notable that Lofven's 1971 clip for "Eagle Rock" bears a strong stylistic resemblance to the video for the 1980 hit "Brass In Pocket" by The Pretenders, and it has been speculated that original bassist Pete Farndon may well have seen the Lofven clip when he was working in Australia in the mid-1970s as a member of The Bushwackers.

The first promo clip to combine all the elements of the modern music video is David Bowie's promotional clip for the song The Jean Genie, which was released as single in late 1972 at the height of Bowie's Ziggy Stardust period. Filmed and directed by renowned photographer Mick Rock, this genre-defining four-minute film was produced for less than $350, shot in one day in San Francisco on 28th October 1972, and edited in less than two days.

The Swedish music group, ABBA, used promotional films throughout the 1970's to promote themselves in other countries when travelling or touring abroad became difficult. Almost all of these videos were directed by Chocolat and My Life as a Dog director, Lasse Hallström.

Modern era

The key innovation in the development of the modern music video was of course video recording and editing processes, along with the development of a number of related effects such as chroma-key. The advent of high-quality colour videotape recorders and portable video cameras coincided with the DIY ethos of the New Wave era and this enabled many pop acts to produce promotional videos quickly and cheaply, in comparison to the relatively high costs of using film. However, as the genre developed music video directors increasingly turned to 35mm film as the preferred medium, while others mixed film and video. By the mid-1980s releasing a music video to accompany a new single had become standard, and acts like The Jacksons sought to gain a commercial edge by creating lavish music videos with million dollar budgets; most notable with the video for "Can You Feel It".

The first music videos were produced by ex-Monkee Michael Nesmith who started making short musical films for Saturday Night Live in 1979. In 1981, he released Elephant Parts, the first video album and first winner of a Grammy for music video directed by William Dear. A further experiment on NBC television called Television Parts was not successful, due to network meddling (notably an intrusive laugh track and corny gags). The early self-produced music videos by Devo, including the pioneering compilation "The Truth About Devolution" directed by Chuck Statler, were also important (if somewhat subversive) developments in the evolution of the genre and these Devo video cassette releases were arguably among the first true long-form video productions. The USA Cable Network program Night Flight was one of the first American programs to showcase these videos as an art form. Premiering in June 1981, Night Flight predated MTV's launch by two months.

In the UK the importance of Top of the Pops to promote a single created an environment of innovation and competition amongst bands and record labels as the show's producers placed strict limits on the number of videos it would use - therefore a good video would increase a song's sales as viewers hoped to see the video again the following week. David Bowie scored his first UK number one in nearly a decade thanks to director David Mallets' eye catching promo for "Ashes to Ashes" . Another act to succeed from this tactic was "Madness" who shot on 16mm and 35mm short micro-comedic films.

"Top of the Pops" was censorus in its approach to video content so another approach was for an act to produce a promo that would be banned or edited and so use the resulting controversy and publicity to promote the release. Early examples of this tactic were Duran Duran's "Girls on Film" and Frankie Goes to Hollywood with "Relax" directed by Bernard Rose.

Although little acknowledged outside Australia, it is arguable that the 1970s-1980s Australian TV pop show Countdown -- and to a lesser extent its commercial competitors Sounds and Nightmoves -- were important precursors to MTV.

Countdown, which was based on Top Of The Pops, hit of in Australia but other countries quickly followed the format. At its highpoint during most of the 1980s it was to be aired in 22 countries including TV Europe. In 1978 the Dutch TV-broadcasting company Veronica started a Dutch version of Countdown which during the 80s had Adam Curry as its best known presenter. The program gained international significance in the recording industry in the late 1970s and early 80s. Produced on a shoestring by the government-owned ABC national TV network, its low budget, and Australia's distance proved to be influential factors in the show's early preference for music video. The relative rarity of visits by international artists to Australia and the availability of high-quality, free promotional films meant that Countdown soon came to rely heavily on music videos in order to feature such performers.

The show's talent coordinator Ian Meldrum and his producers quickly realised that these music videos were becoming an important new commodity in music marketing. For the first time, pre-produced music videos gave TV the opportunity to present pop music in a format that rivalled or even exceed the impact of radio airplay, and it was soon apparent that Countdown could single-handedly break new pop acts and new songs by established artists -- a role that up until then been the exclusive preserve of radio.

Although Countdown continued to rely heavily on studio appearances by local and visiting acts, competing shows like Sounds lacked the resources to present regular studio performances, so they were soon using music videos almost exclusively. As the Eighties progressed, the ability to use music videos to give bands the best possible presentation saw record companies making more, and more lavish, promotional videos.

In 1980 New Zealand group Split Enz had major success with the single "I Got You" and the album True Colours, and later that year they became one of the first bands in the world to produce a complete set of music videos for each song on the album and to market these on video cassette -- the so-called video album. This was followed a year later by the first American video album, The Completion Backwards principle directed by Michael Cotten of The Tubes.

Realising the potential of music video, Countdown negotiated a controversial deal with local record labels, giving them first refusal and a period of exclusive use for any new video that came into the country, and with its nationwide reach and huge audience, Countdown was able to use music videos to break a number of important new local and overseas acts, notably ABBA, Queen, Meat Loaf, Blondie, Devo, Cyndi Lauper and Madonna. This early success in Australia in turn enabled these acts to gain airplay and TV exposure and score breakthrough hits in their home countries.

During the 1980s promotional videos became pretty much de rigueur for most recording artists, a rise which was famously parodied by UK BBC television comedy program Not The Nine O'Clock News who produced a spoof music video; "Nice Video, Shame About The Song". Frank Zappa also parodied the excesses of the genre in his satirical song "Be In My Video".

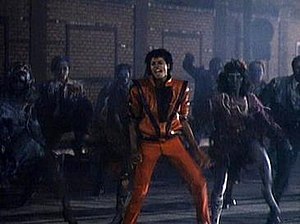

In the early to mid 1980s, artists started to use more sophisticated effects in their videos, and added a storyline or plot to the music video. Michael Jackson was the first artist to create the concept of the short film. A short film is a music video that has a beginning, middle and end. He did this in a small way with Billie Jean, directed by Steve Barron, then in a West Side Story way with director Bob Giraldi's Beat It, but it wasn't until the 1984 release of the Thriller short film that he took the music video format to another level. Thriller was a 14-minute-long music video with a clear beginning, middle and ending. Along with the plot, it also had ahead-of-its-time special effects and a memorable dance sequence which has been mimicked ever since this video was released. The video was directed by John Landis. Jackson then went on to make more famous short films such as, Bad (directed by Martin Scorsese), Smooth Criminal, Remember the Time, Black or White, Scream, Earth Song and Ghosts.

A non-representational music video is one in which the musical artist is never shown. Because music videos are mainly intended to promote the artist, such videos are rare; two early 1980s examples, however, are Bruce Springsteen's Atlantic City directed by Arnold Levine, and Penelope Spheeris' David Bowie/Queen's Under Pressure. Blues Traveler spoofs the non-representational style in its video for the song Runaround, in which a thin, stylish group of pretenders lip-synch the music while the real band performs backstage. Almost all of the videos by Tool are non-representational.

MTV

In 1981, the U.S. video channel MTV launched, beginning an era of 24-hour-a-day music on television. (The first video broadcast was "Video Killed the Radio Star", by The Buggles.) With this new outlet for material, the music video would, by the mid-1980s, grow to play a central role in popular music marketing. Many important acts of this period, most notably Madonna, owed a great deal of their success to the skilful construction and seductive appeal of their videos. Some academics have compared music video to silent film, and it is suggested that stars like Madonna have (often quite deliberately) constructed an image that in many ways echoes the image of the great stars of the silent era such as Greta Garbo. Although many see MTV as the start of a "golden era" of music videos and the unparalleled success of a new artform in popular culture, others see it as hastening the death of the true musical artist, because physical appeal is now critical to popularity to an unprecedented degree.

In the information technology era, music videos now approach the popularity of the songs themselves, being sold in collections on video tape and DVD. Enthusiasts of music videos sometimes watch them muted purely for their aesthetic value. Instead of watching the video for the music, (the basis for the artform), the videos are appreciated for their visual qualities, while viewers remain uninterested in the audio portion of the performance. This is a normal sociological reaction, some say, to the increasing trend in the music business to focus on visual appeal of artists, rather than the quality of the music. Critics say that the corporate music managers, over the course of logical and calculated business decisions, have sought to capitalize on the sex appeal of females in music videos rather than in choosing less profitable musicianship-based music.

Music video directors and creative rights

Since December 1992, when MTV began listing directors with the artist and song credits, music videos have increasingly become an auteur's medium. Few if any filmmakers train specifically to make music videos, and very few can afford to make them exclusively. Most split their time between videos and other film projects. Music video directors - who generally conceive, write, and direct their videos - currently receive no authorship, creative rights, profit participation or residual income from DVDs, iTunes, and other new media on which their work may appear.

However, those features of the industry that tend to make music video direction a less-than-lucrative profession, have also made the medium an exciting art-form, one defined by the cross-pollination of ideas and approaches from various disciplines. Music video directors, like most filmmakers in general, emerge from disparate backgrounds, and don't share much in the way of common thinking or set-in-stone pedagogy, bringing to the field a diversity of experience.

Music video censorship

As the concept and medium of a music video is a form of artistic expression, artists have been on many occasions censored if their content is deemed offensive. What may be considered offensive will differ in countries due to censorship laws and local customs and ethics. In most cases, the record label will provide and distribute videos edited or provide both censored and uncensored videos for an artist. In some cases, it has been known for music videos to be banned in their entirety as they have been deemed far too offensive to be broadcast. The first video to be banned by MTV was "Girls On Film" by Duran Duran in 1981 because it contained full frontal nudity; it was also banned by the BBC. In 1989, Cher's "If I Could Turn Back Time" video (where the singer performs the song in an extremely revealing body suit surrounded by a ship full of cheering sailors) was also banned by MTV.

In 1991 the dance segment of Michael Jackson's "Black or White" was cut because it showed Michael Jackson inappropriately touching himself in the dance segment. Michael Jackson's most controversial video, "They Dont Care About Us" was banned from MTV, VH1, and BBC because of the alleged anti-Semitic message in the song and the visuals in the background of "The Prison Version" of the video. In 2001, Madonna's "What It Feels Like For A Girl" was banned by MTV due to its graphic depiction of violence. Madonna's music video for the song "Justify My Love" was banned due to its depiction of sadomasochism, homosexuality, cross-dressing, and group sex. Madonna pulled her "American Life" video because of its controversial military imagery that seemed inappropriate once the second American war in Iraq began; subsequently, a new video was made for the song. The Prodigy's video for "Smack My Bitch Up" was banned in some countries due to depictions of drug use and nudity. The Prodigy's video for "Firestarter" was banned by the BBC because of its references to arson.

As of 2005, the Egyptian state censorship committee has banned at least 20 music videos which featured sexual connotations due to Muslim ethical viewpoints. The Sex Pistols' video for "God Save the Queen" was banned by the BBC for its anti-royal sentiment. A seemingly innocuous video for "Losing My Religion" by R.E.M. has been banned in Ireland due to its religious imagery. In 2004, many family groups and politicians lobbied for the banning of the Eric Prydz video "Call On Me" for containing soft pornography, however, the video was not banned. At some point in the past, the video for (S)aint by Marilyn Manson was banned by that artist's label due to its violence and sexual content.

Internet

The earliest purveyors of music videos on the internet were members of IRC-based groups who took the time to record music videos as they appeared on television, then digitising them and exchanging the .mpg files via IRC channels. As broadband Internet access has become available more widely, various initiatives have been made to capitalise on the continued interest in music videos. MTV itself now provides streams of artists' music videos, while AOL's recently launched AOL Music features a vast collection of advertising supported downloadable videos. The internet has become the primary growth income market for Record Company produced music videos. At its launch, Apple's iTunes Music Store provided a section of free music videos in high quality compression to be watched via the iTunes application. More recently the iTunes Music Store has begun selling music videos for use on Apple's recently introduced iPod with video playback capability.

Another new phenomenon, deriving from the popularity of blogging, is the use of so-called music video "codes", lines of HTML code including links to music videos that the individual can simply copy and paste into their blog in order to feature a given video streaming on it. YouTube, Google video, IFilm and MySpace have become primary venues for viewing videos. YouTube is claiming up to six million viral video streams a day. The RIAA has recently issued cease-and-desist letters to YouTube users to block the sharing of videos.

Unofficial music videos

With the advent of easy distribution over the internet and cheap video-editing software, a number of fan-created videos began appearing as of the late 1990s. These are typically made by synchronizing existing footage from other sources, such as television series or movie, with the song. In the case of AMVs the source material is drawn from Japanese anime (see anime music video) or from American animation series. Since neither the music nor the film footage is typically licensed, distributing these videos is usually copyright infringement on both counts. Singular examples of unofficial videos include one made for Danger Mouse's illegal mash-up of the Jay-Z track "Encore" with music sampled from The Beatles' White Album, in which concert footage of The Beatles is remixed with footage of Jay-Z and rap dancers, as well as a recent politically charged video by Franklin Lopez of subMedia, cut from television footage of the Katrina aftermath, set to an unofficial remix of Kanye West's "Gold Digger", inspired by the rap-artist's comment "George Bush doesn't care about black people."

Timeline

- 1941: A new invention hits clubs and bars in the USA: The Panoram Soundie is a jukebox that plays short videoclips along with the music.

- 1956: Hollywood discovers the genre of music-centered films. A wave of rock'n'roll films begins (Rock Around the Clock, Don't Knock the Rock, Shake, Rattle and Rock, Rock Pretty Baby, The Girl Can't Help It), and the famous Elvis Presley movies. Some of these films integrated musical performances into a story, others were simply revues.

- 1960: In France a re-invention of the Soundie, the Scopitone, gains limited success.

- 1962: British Television invents a new form of music television. Shows like Top Of The Pops, Ready! Steady! Go! and Oh, Boy started as band vehicles and became huge hits.

- 1964: The US-Television market adapts the format. Hullabaloo is one of the first US shows of this kind, followed by Shindig! (NBC) and American Bandstand; The Beatles star in A Hard Day's Night

- 1966: The first conceptual promos are aired, for the Beatles' "Paperback Writer" and "Rain". Early in 1967, even more ambitious videos are released for "Penny Lane" and "Strawberry Fields Forever".

- 1970: The record industry discovers these TV-Shows as a great opportunity to promote their artists. They focus on producing short "Promos", early music videos which started to replace the live performance of the artist on the TV-stage.

- 1975: "Bohemian Rhapsody" a groundbreaking video released by Queen marked the beginning of the video era and set the language for the modern music video.

- 1980: "Ashes to Ashes" which is considered as a groundbreaking video is released by David Bowie

- 1981: MTV, the first 24-hour satellite music channel, launches. Initially few cable TV operators carry it, but it rapidly becomes a major hit and cultural icon.

- 1984: Michael Jackson's short film Thriller is released, changing the concept of music videos forever. The Making of Thriller home video was also released in 1984. It was the first ever video about the making of a music video.

- 1986: Sledgehammer, the groundbreaking video from Peter Gabriel, is first shown.

- 1989: MTV renames its "Video Vanguard Award" to the " Michael Jackson Vanguard Award" in honor of Michael Jackson for his contributions to the art of music video.

- 1989: Madonna's controversial video for Like a Prayer is released.

- 1992: MTV begins to credit music video directors.

- 1992: Guns N' Roses's groundbreaking video for "November Rain" is released and remains as one of the costliest ever produced.

- 1996: Pop-up Video is first aired on VH1.

- 1996: M2 is launched as a 24-hour music video channel, as MTV has largely replaced videos with other content.

- 1999: M2 is renamed to MTV2.

- 2002: MTV Hits is launched as MTV2 is gradually showing fewer music videos.

- 2006: The Norwegian unsigned band Rektor makes the worlds first playable videogame music video game http://www.rektor.no.

Music video stations

Here are some of the most popular music video stations from around the world:

|

|

Music video shows

Notes

- ^ Clarke, pg. 39

See also

- List of most expensive music videos

- Music video director

- List of censored music videos

- First 62 Videos aired on MTV

- Video clip

References

- Banks, Jack (1996) Monopoly Television: Mtv's Quest to Control the Music Westview Press ISBN 0813318203

- Clarke, Donald (1995). The Rise and Fall of Popular Music. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0312115733.

- Denisoff, R. Serge (1991) Inside MTV New Brunswick: Transaction publishers ISBN 0887388647

- Durant, Alan (1984). Cited in Middleton, Richard (1990/2002). Studying Popular Music. Philadelphia: Open University Press. ISBN 0335152759.

- Frith, Simon, Andrew Goodwin & Lawrence Grossberg (1993) Sound & Vision. The music video reader London: Routledge ISBN 0415094313

- Goodwin, Andrew (1992) Dancing in the Distraction Factory : Music Television and Popular Culture University of Minnesota Press ISBN 0816620636

- Kaplan, E. Ann (1987) Rocking Around the Clock. Music Television, Postmodernism, and Consumer Culture London & New York: Routledge ISBN 0415030056

- Keazor, Henry/Wübbena, Thorsten (2005). Video thrills the Radio Star. Musikvideos: Geschichte, Themen, Analysen, Bielefeld. ISBN 3899423836 (see also: vttrs.de)

- Kleiler, David (1997) You Stand There: Making Music Video Three Rivers Press ISBN 0609800361

- Middleton, Richard (1990/2002). Studying Popular Music. Philadelphia: Open University Press. ISBN 0335152759.

- Shore, Michael (1984) The Rolling Stone book of rock video New York: Quill ISBN 0688039162

- Vernallis, Carol (2004) Experiencing Music Video: Aesthetics and Cultural Context Columbia University Press ISBN 0231117981

- ALTROGGE, Michael: Tönende Bilder: interdisziplinäre Studie zu Musik und Bildern in Videoclips und ihrer Bedeutung für Jugendliche. Band 1: Das Feld und die Theorie. Berlin: Vistas 2001

- ALTROGGE, Michael: Tönende Bilder. Das Material: Die Musikvideos. Bd 2. Berlin: Vistas 2001

- ALTROGGE, Michael: Tönende Bilder: interdisziplinäre Studie zu Musik und Bildern in Videoclips

und ihrer Bedeutung für Jugendliche. Band 3: Die Rezeption: Strukturen der Wahrnehmung. Berlin: Vistas 2001

- Bühler, Gerhard (2002): Postmoderne auf dem Bildschirm – auf der Leinwand. Musikvideos, Werbespots und David Lynchs WILD AT HEART

- Helms, Dietrich; Thomas Phleps (Hrsg.): Clipped Differences. Geschlechterrepräsentation im Musikvideo. Bielefeld: Transcript 2003

- KEAZOR, Henry / WÜBBENA, Thorsten: Video Thrills The Radio Star. Musikvideos: Geschichte, Themen, Analysen. Bielefeld: 2005

- Kirsch, Arlett: Musik im Fernsehen. Eine auditive Darstellungsform in einem audiovisuellen Medium. Berlin: Wiku 2002

- KURP, Matthias / HAUSCHILD, Claudia & WIESE, Klemens (2002): Musikfernsehen in Deutschland. Politische, soziologische und medienökonomische Aspekte

- NEUMANN-BRAUN, Klaus / SCHMIDT, Axel / MAI, Manfred (2003): Popvisionen. Links in die Zukunft

- Neumann-Braun, Klaus / Mikos,Lothar: Videoclips und Musikfernsehen. Eine problemorientierte Kommentierung der aktuellen Forschungsliteratur; Berlin: Vistas 2006

- Quandt, Thorsten (1997). Musikvideos im Alltag Jugendlicher. Umfeldanalyse und qualitative Rezeptionsstudie. Deutscher Universitätsverlag

- G.Turner, Video Clips and Popular Music, in Australian Journal of Cultural Studies 1/1,1983, 107-110

- C.Hausheer/A.Schönholzer (Hrsg.), Visueller Sound. Musikvideos zwischen Avantgarde und Populärkultur, Luzern 1994