Reculver

| Reculver | |

|---|---|

The twin towers of St Mary's Church | |

| Area | 2.79 sq mi (7.2 km2) [1] |

| Population | 135 [2] |

| • Density | 48/sq mi (19/km2) |

| OS grid reference | TR2269 |

| Civil parish | |

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | HERNE BAY |

| Postcode district | CT6 |

| Dialling code | 01227 |

| Police | Kent |

| Fire | Kent |

| Ambulance | South East Coast |

| UK Parliament | |

Reculver is a village and coastal resort about 3 miles (5 km) east of Herne Bay in south-east England, in a ward of the same name, in the City of Canterbury district of Kent. It is about 30 miles (48 km) east by north of the county town of Maidstone, and about 58 miles (93 km) east by south from London. Reculver once occupied a strategic location at the north-western end of the Wantsum Channel, a sea lane which separated the Isle of Thanet and the Kent mainland until the late Middle Ages. This led the Romans to build a small fort there at the time of their conquest of Britain in 43 AD, and, starting late in the 2nd century, they built a larger fort, or castrum, called Regulbium, which later was part of the chain of Saxon Shore forts. The military connection resumed in the Second World War, when Barnes Wallis's bouncing bombs were tested in the sea off Reculver.

After the Romans left Britain early in the 5th century, Reculver became a landed estate of the Anglo-Saxon kings of Kent. The site of the Roman fort was given over for the establishment of a monastery dedicated to St Mary in 669 AD, and King Eadberht II of Kent was buried there in the 760s. During the Middle Ages Reculver was a thriving township with a weekly market and a yearly fair, and it was a member of the Cinque Port of Sandwich. The twin spires of the church became a landmark for mariners known as the Twin Sisters, and the 19th-century facade of St John's Cathedral in Parramatta, a suburb of Sydney, Australia, is a copy of that at Reculver.

Reculver declined as the Wantsum Channel silted up, and coastal erosion claimed many buildings constructed on the soft sandy cliffs. The village was largely abandoned in the late 18th century, and most of the church was demolished in the early 19th century. Protecting the ruins and the rest of Reculver from erosion is an ongoing challenge.

The 20th century saw a revival as a tourism industry developed and there are now three caravan parks. The census of 2001 recorded 135 people in the Reculver area, nearly a quarter of whom were in caravans at the time. Reculver Country Park is a Special Protection Area, Site of Special Scientific Interest and Ramsar site, which has rare clifftop meadows and is important for migrating birds.

History

Toponymy

The earliest recorded form of the name, Regulbium, is Celtic in origin, meaning "at the promontory", or "great headland", and, in Old English, this became corrupted to Raculf, sometimes given as Raculfceastre, giving rise to the modern "Reculver".[3][Fn 1] The form "Raculfceastre" includes the Old English place-name element "ceaster", which frequently relates to "a [Roman] city or walled town".[5]

Pre-historic and Roman

Stone Age flint tools have been washed out from the cliffs to the west of Reculver,[6] and a Mesolithic tranchet axe was found at Reculver in 1960, but this was probably a casual loss.[7] Evidence for human settlement at Reculver begins with late Bronze Age and Iron Age ditches, which indicate an "extensive phased settlement",[8] where a Bronze Age palstave and Iron Age gold coins have been found.[9] This was followed by a Roman "fortlet" dating to their conquest of Britain, which began in 43 AD,[10] and a full-size Roman fort, or castrum, called Regulbium, which was started late in the 2nd century: this date is derived in part from a re-construction of a uniquely detailed plaque, fragments of which were found by archaeologists in the 1960s.[11] The plaque effectively records the establishment of the fort, since it records the construction of two of its principal buildings, the basilica and the sacellum.[12][Fn 2] These were found by archaeologists, together with probable officers' quarters, barracks and a bath house.[13][Fn 3] A Roman oven was also found 200 feet (61 m) south-east of the fort, which was probably used for drying food such as corn and fish: the main chamber of the oven measured about 16 feet (4.9 m) by 15 feet (4.8 m) overall, and was found to be "unique and cleverly engineered".[15]

The fort was located at what was then the north-eastern extremity of mainland Kent, overlooking the sea lane later known as the Wantsum Channel, which lay between it and the Isle of Thanet: the fort's location thus lay at the "main point of contact in the system [of Saxon Shore forts]",[16] and allowed observation from the fort on all sides.[17] The entrance to the headquarters building, or principia, faced north, indicating that the fort's main gate was on its north side, facing the eponymous promontory and the sea.[18] The fort was connected to the network of Roman roads through a link to Canterbury, about 8.5 miles (14 km) to the south-west.[19] It must also have had a harbour nearby,[19] and, though this has not yet been found, it was probably near to the fort's southern or eastern side.[20][Fn 4] Roman forts were normally accompanied by a civilian settlement, or vicus, and it is clear that significant Roman structures and features existed outside the north and west sides of the fort, mostly in areas now lost to the sea, and that the vicus at Reculver was "extensive".[22][Fn 5] It may have covered "some ten hectares [25 acres] in all."[24]

Towards the end of the 3rd century a Roman naval commander named Carausius was given the task of clearing pirates from the sea between the Roman provinces in Britain, or Britannia, and on the European mainland.[25] In so doing he established a new chain of command, the British part of which was later to pass under the control of a Count of the Saxon Shore. The Notitia Dignitatum, a Roman administrative document of the early 5th century, shows that the fort at Reculver became part of this arrangement, but archaeological evidence indicates that it was abandoned in the 360s.[26]

Monastery and church

After the Roman occupation of Britain ended in about 410, Reculver became a landed estate of the Anglo-Saxon kings of Kent, possibly with a royal toll-station or a "significant coastal trading settlement,"[28] given the types and quantity of coins found there.[28][Fn 6] Other early Anglo-Saxon items found at Reculver include a fragment of a gilt bronze brooch, or fibula, which was originally circular and set with coloured stones or glass,[29][Fn 7] a claw beaker,[31] and pottery.[32] King Æthelberht of Kent was traditionally said to have moved his royal court there from Canterbury in about 597, for example by John Duncombe in 1784,[33] and to have built a palace on the site of the Roman ruins;[34] but, while archaeological excavation has shown no evidence of this, Æthelberht's household would have been peripatetic, and the story has been described as probably a "pious legend".[35][Fn 8] A church was built on the site of the Roman fort in about 669, when King Ecgberht of Kent granted land for the foundation of a monastery there, which was dedicated to St Mary.[38]

The monastery developed as the centre of a "large estate, a manor and a parish",[36] and, by the early 9th century, it had become "extremely wealthy",[39] but it then fell under the control of the archbishops of Canterbury.[40] By the 10th century the church and the estate were in the hands of the kings of Wessex, though the church may have remained a monastery, despite the likelihood of Viking attacks.[41] The church and the estate were given back to the archbishops of Canterbury in 949 by King Eadred of England, at which time the estate centred on Reculver included Hoath, Herne and land in the west of the Isle of Thanet.[42]

By 1066 the monastery had become a parish church.[42] However, in 1086 Reculver was named in Domesday Book as a hundred, with the estate centred on Reculver valued at £42.7s. (£42.35);[43] and, in the 13th century, the parish of Reculver remained one of "exceptional wealth".[44] The church building was extended considerably during the Middle Ages, including the addition of the towers in the 12th century,[45] indicating that the settlement at Reculver had become a "thriving township",[36] with "dozens of houses".[46][Fn 9] The parish was broken up in 1310, when chapelries at Herne and, on the Isle of Thanet, St Nicholas-at-Wade and All Saints were converted into parishes, though Hoath was still a perpetual curacy belonging to Reculver parish in the 20th century.[48] Records for the poll tax of 1377 show that there were then 364 individuals of 14 years and above, not including "honest beggars", in the reduced parish of Reculver, who paid a total £6.1s.4d. (£6.07) towards the tax.[49][Fn 10]

Decline and loss to the sea

The thriving township of medieval Reculver depended partly on its position on a maritime trade route through the Wantsum Channel, already present in Anglo-Saxon times and exemplified by Reculver's membership of the Cinque Port of Sandwich later in the Middle Ages.[54] The importance of the Wantsum Channel was such that, when the River Thames froze in 1269, trade between Sandwich and London had to be carried out overland.[55] Historical records for the channel are sparse after 1269, perhaps "because the route was so well known as to be taken for granted [in the Middle Ages], the whole waterway from London to Sandwich being occasionally spoken of as the 'Thames'".[56] But silting and inning had closed the channel to trading vessels by about 1460,[55] and the first bridge was built over it at Sarre in 1485, since ferries could no longer operate across it.[57][Fn 11]

Reculver was also diminished by coastal erosion. By 1540, when John Leland recorded a visit to Reculver, the coastline to the north had receded to within little more than a quarter of a mile (402 m) of the "Towne [which] at this tyme [was] but Village lyke".[60] Soon after, in 1576, William Lambarde described Reculver as "poore and simple".[61] In 1588 there were 165 communicants – people in Reculver parish taking part in services of holy communion at the church – and in 1640 there were 169,[34] but a map of about 1630 shows that the church then stood only about 500 feet (152 m) from the shore.[62][Fn 12] In January 1658 the local justices of the peace were petitioned concerning "encroachments of the sea ... [which had] since Michaelmas last [29 September 1657] encroached on the land near six rods [99 feet (30 m)], and will doubtless do more harm".[63] The village's failure to support two "beer shops" in the 1660s points clearly to a declining population,[36] and the village was mostly abandoned around the end of the 18th century, its residents moving to Hillborough, about 1.25 miles (2 km) south-west of Reculver but within Reculver parish.[64][Fn 13]

Concern about erosion of the cliff on which the church stood, and the possible inundation of the village, had led the commissioners of sewers to install costly sea defences consisting of planking and piling prior to 1783, when it was reported that the commissioners had adopted a scheme proposed by Sir Thomas Page to protect the church: the sea defences had proven counter-productive, since sea water collected behind them and continued to undermine the cliff.[66] Prior to this, according to John Duncombe, "the commissioners of sewers, and the occupiers who pay scots, [had] no view nor interest but to secure the level [ground], which must be overflowed when the hill is washed away.[67] By 1787 Reculver had "dwindled into an insignificant village, thinly decked with the cottages of fishermen and smugglers."[68][Fn 14]

[At about this time,] from the present shore as far as a place called the Black Rock, seen at lowwater mark, where tradition says, a parish church once stood, there [were] found quantities of tiles, bricks, fragments of walls, tesselated pavements, and other marks of a ruinated town, and the household furniture, dress, and equipment of the horses belonging to the inhabitants of it, [were] continually found among the sands ...

In September 1804 a high tide and strong winds led to the destruction of five houses, one of which was "an ancient building, immediately opposite the public house, and had the appearance of having been part of some monastic erection".[71] The following year, according to a set of notes written by parish clerk John Brett, "Reculver Church and willage stood in safety",[72] but in 1806 the sea began to encroach on the village, and in 1807 the local farmers dismantled the sea defences, after which "the village became a total [wreck] to the mercy of the sea."[72][Fn 16]

A further scheme to protect the cliff and church was proposed by John Rennie, but a decision was taken on 12 January 1808 to demolish the church.[75] By March 1809, erosion of the cliff had brought it to within 12 feet (4 m) of the church, and demolition was begun in September that year.[76][Fn 17] Trinity House intervened to ensure that the towers were preserved as a navigational aid, and in 1810 it bought what was left of the structure for £100 and built the first groynes, designed to protect the cliff on which the ruined church stands.[82] The vicarage was abandoned at the same time as the church, or a little earlier,[36][Fn 18] and a replacement parish church was built at Hillborough, opening in 1813.[84]

After the sea undermined the foundations of the Hoy and Anchor Inn at Reculver in January 1808, the building was taken down and the redundant vicarage was used as a temporary replacement under the same name.[85][Fn 19] Although it was reported in 1800 that there were then only five or six houses left at Reculver,[34] a new Hoy and Anchor Inn was built by 1809,[87] and this was renamed as the King Ethelbert Inn by 1838.[88][Fn 20] Further construction work is indicated by a stone over the doorway to the inn bearing a date of 1843,[93] and it was later extended into the form in which it stands today, "probably ... in 1883".[36][Fn 21]

Today the site of the church is managed by English Heritage, and the village has all but disappeared.[Fn 22] The present appearance of the cliff below the church, a grassy slope above a large stone groyne, was in place by April 1867, and the sea defences there continue to be maintained by Trinity House.[95] In 2000 the surviving fragments of an early medieval cross which once stood inside the old church were used to design a Millennium Cross to commemorate two thousand years of Christianity. This stands at the entrance to the car park and was commissioned by Canterbury City Council.[96]

Bouncing bombs

During the Second World War, the Reculver coastline was one location used to test Barnes Wallis's bouncing bomb prototypes.[97] Reculver was chosen for its seclusion,[98] though the presence of the church towers as a clear marker for the bombers, and the potential to recover prototypes owing to the shallow water, probably were also factors.[99] Different, inert versions of the bomb were tested at Reculver, leading to the development of the operational version known as "Upkeep".[100] This bomb was used by the RAF's 617 Squadron in Operation Chastise, otherwise known as the Dambuster raids, in which dams in the Ruhr district of Germany were attacked on the night of 16–17 May 1943 by formations of Lancaster bombers. The operation was led by Wing Commander Guy Gibson, for which he was awarded the Victoria Cross. On 17 May 2003, a Lancaster bomber overflew the Reculver testing site to commemorate the 60th anniversary of the exploit.[101]

Two prototype bouncing bombs, about 6 feet (2 m) long and 3 feet (1 m) wide, lay in marshland behind the sea wall at Reculver until about 1977, when they were removed by the Army.[99] Other prototypes were recovered from the shoreline at Reculver in 1997, one of which is displayed in Herne Bay Museum and Gallery, a little over 3 miles (5 km) to the west of Reculver.[102] Others are on display in Dover Castle and in the Spitfire & Hurricane Memorial Museum at the former RAF Manston, on the Isle of Thanet.[103]

Governance

In the 10th-century charter by which King Eadred gave Reculver to the archbishops of Canterbury, the boundary of the mainland part of the estate was about the same as those for the parishes of Reculver, Hoath and Herne, and the estate included part of the Isle of Thanet.[105][Fn 23] In 1086, Domesday Book named Reculver as a hundred, meaning that it was probably then the meeting-place for the local hundred court.[106] As well as Reculver itself, the hundred of Reculver included Hoath and Herne, and it may also have included the neighbouring area of Thanet, as it did in 1274–75, when the local hundred was named after Bleangate in a detached part of Chislet parish, and was divided into northern and southern halves.[107][Fn 24] By 1540 Bleangate hundred no longer included land on Thanet, its members being listed then as Sturry, Chislet, Reculver and Herne for the archaic taxes known as "fifteenths and tenths",[110][Fn 25] and in 1659 they were listed as Chislet, Herne, Hoath, Reculver, Stourmouth, Sturry and Westbere.[113] In 1808 the members of the northern half-hundred, or "Bleangate Upper", were listed as Herne, Reculver, Stourmouth and Hoath.[114] The constable for the northern half-hundred was chosen at the court leet of the manor of Reculver, which by 1800 was usually held at Herne.[115][Fn 26]

Reculver parish was represented by two tithings – known in Kent as "borghs"[47] – in the Hundred Rolls of 1274–75 and, 400 years later, for the purposes of the Hearth Tax, levied between 1662 and 1689.[118] In 1274–75 these borghs appear as Reculver borgh and Brookgate borgh;[108] in 1663 they appear as Reculver Street borgh and Brookgate borgh, which were recorded under a parish heading for Reculver, together with Hoath borgh;[119] and in 1673 Reculver borgh and Brookgate borgh were recorded under a heading for Herne parish, and Hoath was recorded under its own parish heading.[120] However, borghs in Kent, and tithings generally, were related to the manorial and hundredal administration of the county, rather than to the parishes in which they lay.[121]

The parishes of Herne, to the west of Reculver, and St Nicholas-at-Wade on the Isle of Thanet were created from parts of Reculver parish in 1310,[122] though these new parishes continued to have a subordinate relationship with the parish of Reculver into the 19th century, while Hoath remained a perpetual curacy of Reculver into the 20th.[123] Thereafter Reculver's parish boundary, enclosing an area of about 2 square miles (5 km2), remained the same for both ecclesiastical and civil purposes until 1934.[124] Included were Reculver, Hillborough, Bishopstone and Brook (now Brook Farm), and the parish extended west almost to Beltinge, in Herne parish, and to Broomfield in the south-west – where the boundary with Herne parish ran along the centre of the main thoroughfare, now Margate Road – and it was bounded in open country on the south-east and east by the parish of Chislet.[125][Fn 27] In 1934 the civil functions of the parish were merged into the civil parish of Herne Bay.[124] Conversely, Reculver is now in an electoral ward of the same name, in the local government district of Canterbury, which includes Beltinge, Bishopstone, Brook Farm and Hillborough, and extends into the eastern part of the town of Herne Bay.[126] This ward has three seats on Canterbury City Council, and, in the local elections of 2011, these seats were won by the existing holders Jennie Edwards, Gillian Reuby and Ann Taylor, all Conservative.[127]

At the national level Reculver is in the English parliamentary constituency of North Thanet, for which Roger Gale (Conservative) has been MP since 1983.[128] In the general election of 2010, Gale won 22,826 votes (52.57%), giving him a majority of 13,528. Labour won 9,298 votes (21.42%), the Liberal Democrats 8,400 (19.35%), and the United Kingdom Independence Party 2,819 (6.5%).[128] For European elections Reculver is in the South East England constituency. MEPs elected in the European election of 2009 were Daniel Hannan, Richard Ashworth, Nirj Deva and James Elles (Conservative); Sharon Bowles and Catherine Bearder (Liberal Democrats); Nigel Farage and Marta Andreasen (United Kingdom Independence Party); Caroline Lucas (Green Party; replaced by Keith Taylor in 2010);[129][Fn 28] and Peter Skinner (Labour).[131]

Geography

Reculver is located on the north coast of Kent about 3 miles (5 km) east of Herne Bay, 8 miles (13 km) west of Margate, 30 miles (48 km) east by north of the county town of Maidstone and 58 miles (93 km) east by south from London. It once occupied a strategic location on routes between continental Europe and the east coast of England, but this has been obscured by sedimentation and coastal erosion.[132] In the Iron Age it lay on a promontory at the north-western entrance to the Wantsum Channel, a sea lane between the Isle of Thanet and the Kent mainland, which silted up during the Middle Ages.[133][Fn 29] The ruins of a Roman fort and a medieval church stand on the remains of the promontory, a low hill with a maximum height of 50 feet (15 m), which is the "last seaward extension of the Blean Hills."[23]

Sediments laid down around 55 million years ago are particularly well displayed in the cliffs at Reculver.[134] Nearby Herne Bay is the type location for the Thanet Sand Formation, a fine-grained sand that can be clayey and glauconitic and is of Thanetian (late Paleocene) age.[135] It rests unconformably on the Chalk Group[135] and forms the base of the cliffs in the Reculver and Herne Bay area.[136] Above the Thanet Sand are the Upnor Formation, a medium sandstone,[137] and the sandy clays of the Harwich Formation at the Paleocene/Eocene boundary.[138] The highest cliffs, rising to a maximum height of about 115 feet (35 m) to the west of Reculver,[139] have a cap of London Clay,[136] a fine silty clay of Eocene age.[140] The surface consists mainly of flint gravel with some areas of brickearth, both of which are glacial deposits.[141]

These rocks are easily washed away by the sea.[144] It has been estimated that the Roman fort was originally about 1 mile (1.6 km) from the sea to the north, but the cliffs are eroding at a rate of approximately 3.28 feet (1 m) a year.[145] Coastal erosion had washed away most of Reculver village by 1800, leading residents to re-locate to Hillborough, within Reculver parish.[146] A plan is in place to manage this erosion whereby some parts of the coastline such as the country park will be allowed to continue eroding, and others – including the site of the Roman fort and the medieval church – will be protected from further erosion.[147] New sea defences were built in the 1990s, including covering the beaches around the church with boulders.[148]

The warmest time of year in Kent is in July and August, with average maximum temperatures of around 21 °C (70 °F), and the coolest is in January and February, with average minimum temperatures of around 1 °C (34 °F).[149] Average maximum and minimum temperatures are about 0.5 °C higher than they are nationally.[150] Locations on the north coast of Kent, like Reculver, are sometimes warmer than areas further inland, owing to the influence of the North Downs to the south.[151] Average annual rainfall in Kent is about 728 millimetres (29 in), with the highest rainfall from October to January.[149] This is lower than the national average annual rainfall of 838 millimetres (33 in).[150] Occasional drought conditions can lead to the imposition of Temporary Use Bans to conserve water supplies,[152] and it was announced in 2013 that a water desalination plant was to be built at Reculver to increase supplies.[153]

Demography

In the census of 1801, the number of people present in the parish of Reculver, enclosing an area of about 2 square miles (5 km2) and including the settlements of Reculver, Hillborough, Bishopstone and part of Broomfield, was given as 252, and this figure remained roughly stable until the 20th century when it increased dramatically: in the census of 1931, the number was given as 829.[154][Fn 31] In 2005 the population of Reculver was estimated to increase from "about twenty [permanent residents] ... to over 1,000 at the height of the [summer] holiday season".[156]

In the 2001 census the relevant census area covered 2.79 square miles (7 km2)[1] and included only Reculver and outlying farms and houses, in which 135 people were found, almost a quarter of whom were in caravans.[2] All were born in the United Kingdom except for three individuals from the Republic of Ireland and three from South Africa. Gender was given as 69 female and 66 male, and the age distribution was 12 individuals aged 0–5 years (8.8%), 16 aged 6–16 years (14%), 30 aged 17–35 years (22.2%), 14 aged 36–45 years (10.3%), 44 aged 46–64 years (32.5%) and 21 aged 65 years and over (15.5%). Half (67) of all the individuals recorded were described as economically active, with 58 of these having employers and nine being self-employed; none were recorded as full-time students or unemployed. Twenty-four people were described as retired (17.7%). Of those aged 16–74 years, 14 (12.8%) were placed at the highest level for education or qualification. Christianity was the only religion represented, by 99 individuals, with 22 recorded as having no religion and 14 whose religion was not stated.[2] From April 2001 to March 2002 the average gross weekly income of households in the ward of Reculver, which includes Beltinge, Bishopstone, Hillborough and most of the eastern part of the town of Herne Bay, was estimated by the Office for National Statistics as £560, or £29,120 per year.[126]

In the 2011 census the relevant census area was identical to Reculver electoral ward, an area of 3.55 square miles (9 km2), including the settlements of Reculver, Beltinge, Bishopstone and Hillborough, and producing information for the area as a whole.[157] Therefore, while the total resident population of the ward at the 2011 census numbered 8,845, detailed information comparable to that of the 2001 census is unavailable.

Economy

In the Middle Ages, Reculver was a member of the Cinque Port of Sandwich.[158] The connection with Sandwich may have begun in the 11th century, and membership of the Cinque Ports involved Reculver in supplying ships and men for the king's use, in return for concessions such as tax exemption.[159] In 1220 King Henry III granted the archbishop of Canterbury a market to be held weekly at Reculver on Thursdays,[160] and an annual fair was held there on Saint Giles's Day, 1 September.[161][Fn 32]

An enclosed area of salt water at Reculver known as the Dene was leased for the breeding of oysters and lobsters in 1867;[163] as of 2014, there is a hatchery for oysters in saltwater ponds on the eastern side of Reculver belonging to a seafood company which is based there.[164] Young oysters are transplanted from the hatchery to the sea bed at Whitstable.[165] Oysters from the "Rutupian shore" – the shoreline around Richborough, a little over 8 miles (13 km) south-east of Reculver – were noted as a delicacy by the 1st–2nd century Roman poet Juvenal,[166] and in 1576 oysters from Reculver itself were "reputed as farre to passe those of Whitstaple, as Whitstaple doe surmount the rest of this shyre [of Kent] in savorie saltnesse."[167] In May 1914, Anglo-Westphalian Kent Coalfield Ltd drilled a borehole at Reculver in search of coal, since it had found a seam of coal 48 feet (14.6 m) thick at nearby Chislet and was developing a colliery there; possible samples of coal were retrieved from a depth of 1,129 feet (344.1 m) at Reculver, but the borehole was abandoned, no workable seam of coal having been found.[168]

Today Reculver is dominated by static caravan parks, the first of which appeared after the Second World War.[169][Fn 33] Also present are a country park, the King Ethelbert public house, which is a free house,[Fn 34] and a nearby shop and cafe.[171] Reculver was defined as a "key heritage area" in 2008, and there are plans for its development as a destination for green tourism.[172][Fn 35] Canterbury City Council's Reculver Masterplan, adopted in 2009, envisaged the creation of 100 touring pitches in its caravan park, south-east of the Roman fort, which was then leased to the Camping and Caravanning Club, partly to address a decline in the static caravan market.[173] In 2013 it was reported that the Camping and Caravanning Club had surrendered its lease on the caravan park and that Canterbury City Council intended to close it and incorporate it into the country park.[174]

Culture and community

Culture

Twin Sisters

A byname for the towers of the ruined church is the "Twin Sisters", and an account of how this first arose was current about a hundred years after its supposed happening in the late 15th century, but in its usual form, for example in a 19th-century travel guide,[175] it is mostly an invention created around "pseudo-historical detail".[176][Fn 36] The Ingoldsby Legends includes a re-invention of the story in which two brothers, Robert and Richard de Birchington, are substituted for the two sisters.[178]

Crying baby

It is reported that the sound of a crying baby is often heard in the grounds of the fort and within the ruins of the church.[179] Archaeological excavations conducted in the 1960s within the fort revealed numerous infant skeletons buried under and in the walls of Roman structures, probably barrack blocks, from which coins were recovered and dated to 270–300 AD.[180] It is unknown whether the babies were selected for burial because they were already dead, perhaps stillborn, or if they were killed for the purpose, but they were probably buried in the buildings as ritual sacrifices.[181][Fn 37] A baby's feeding bottle was also found on its side in an excavated floor and within 10 feet (3 m) of one of the infant skeletons, but it need not have been connected with the burials.[183]

Community facilities

The nearest post office to Reculver is in Beltinge, about 1.9 miles (3 km) to the west-southwest.[184] The nearest general practitioner (GP) surgery is about 1.5 miles (2 km) to the south-west, between Bishopstone and Hillborough, with others located in Beltinge, Herne Bay, Broomfield and St Nicholas-at-Wade.[185] While the nearest general hospital to Reculver is the Queen Victoria Memorial Hospital, about 2.5 miles (4 km) to the west in Herne Bay,[186] the nearest hospital with an Accident and Emergency (A&E) department is the Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother Hospital, about 8.2 miles (13 km) to the east in Margate.[187] The nearest community centre is Reculver and Beltinge Memorial Hall, about 1.9 miles (3 km) to the west-southwest.[188]

Landmarks

Ruined church of St Mary

The medieval towers of the ruined church of St Mary are Reculver's "most dominant features".[190] These towers were added in the late 12th century to an existing church, which was founded in 669, when King Ecgberht of Kent granted land at Reculver to Bassa the priest for the foundation of a monastery.[38] It may be that King Ecgberht's intention in founding a monastery at Reculver was to create an ecclesiastical centre with a strong English element, to counterbalance domination of the Canterbury church by Archbishop Theodore, from Tarsus, now in Turkey, Abbot Hadrian of St Augustine's, from North Africa, probably Cyrenaica, and their equally "non-native followers."[191][Fn 38]

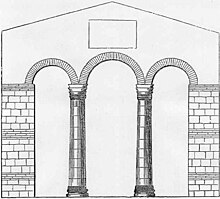

The foundation of this church, sited within the remains of the Roman fort of Regulbium, exemplifies the "widespread practice [in Anglo-Saxon England] of re-using Roman walled places for major churches",[195] and the new church was built "almost completely from demolished Roman structures".[196] The original structure formed a nave measuring 37.5 feet (11.4 m) by 24 feet (7.3 m) and an apsidal chancel, which was externally polygonal but internally round, and was entered from the nave through a triple arch formed by two columns made of limestone from Marquise, in the Pas-de-Calais region of northern France.[197][Fn 39] Around the inside of the apse was a stone bench, and two small rooms, or porticus, were built out from the north and south sides of the chancel, from which they could be accessed.[201][Fn 40] The presence of a stone bench around the inside of the apse has been attributed to influence from the Syrian Church, at a time when its followers were being displaced.[203]

Ten years after the foundation of the monastery, in 679, King Hlothhere of Kent granted lands at Sturry, about 6.2 miles (10 km) south-west of Reculver, and at Sarre, in the western part of the Isle of Thanet, across the Wantsum Channel to the east, to Abbot Berhtwald and to the monastery.[204] The grant was made at Reculver, the charter in which it was recorded was probably written by a Reculver scribe, and the grant of Sarre in particular "must be regarded as a sign of enormous royal favour to the [church at Reculver]".[205][Fn 41] In the original, 7th-century charter recording this grant, Reculver is referred to as a civitas, or city, but this is probably a reference to either its Roman origins or its monastic status, rather than a large population centre.[207] In 692 Reculver's abbot Berhtwald, a former abbot of Glastonbury in Somerset, was elected archbishop of Canterbury.[208] Bede, writing no more than 40 years later, described him as having been well educated in the Bible and experienced in ecclesiastical and monastic affairs,[209] but in terms indicating that Berhtwald was not a scholar.[210]

Further charters show that the monastery at Reculver continued to benefit from Kentish kings in the 8th century, under abbots Heahberht, Deneheah and Hwitred, acquiring lands in Higham Upshire and Sheldwich and exemption from the toll due on one ship at Fordwich,[211] and King Eadberht II of Kent was buried there in the 760s.[212][Fn 42] Other properties belonging to Reculver are mentioned in passing by otherwise unrelated records, such as a pre-existing estate at Higham Upshire, land probably in the High Weald area of Kent, from which iron may have been sourced for use or sale at or on behalf of Reculver, and an unidentified property named Dunwaling land in the district of Eastry.[215] By the early 9th century Reculver had become "extremely wealthy",[39] but from then on it appears in records as "essentially a piece of property".[40] In 811 control of Reculver was in the hands of Archbishop Wulfred of Canterbury, who is recorded as having deprived Reculver of some of its land,[216] and soon after Reculver featured in a "monumental showdown"[40] between Archbishop Wulfred and King Coenwulf of Mercia over the control of monasteries,[40] to which the subsequent control of Reculver by archbishops of Canterbury has been attributed.[217] By the 10th century Reculver had ceased to be an important church in Kent, and, together with its territory, it was under the control of the kings of Wessex.[218] In a charter of 949 King Eadred of England gave Reculver back to the archbishops of Canterbury, at which time the estate included Hoath and Herne, land at Sarre, in Thanet, and land at Chilmington, about 23.5 miles (37.8 km) south-west of Reculver.[219][Fn 43]

Reculver may have remained home to a monastic community into the 10th century, despite the likelihood of Viking attacks.[41][Fn 44] A monk of Reculver named Ymar was recorded as a saint in the early 15th century by Thomas Elmham, who found the name in a martyrology, and wrote that Ymar was buried in St John’s church, Margate: Ymar was probably killed by Danes in the 10th century, and hence regarded as a martyr.[222] The last abbot is recorded as "Wenredus",[223] though when he was abbot is unknown. In the first half of the 11th century the church was referred to as a monastery governed by a dean named Givehard (Guichardus),[224] with two monks named Fresnot and Tancrad, indicating the presence of a religious community of Continental origin, possibly Flemings.[42] By 1066 the monastery had become a parish church, with no baptismal function, and its territory had become part of the endowment of the archbishops of Canterbury.[42] Domesday Book records the archbishop's annual income from Reculver in 1086 as £42.7s. (£42.35): this value can be compared with, for example, the £20 due to him from the manor of Maidstone, and £50 from the borough of Sandwich.[43][Fn 45] Included in the Domesday account for Reculver, as well as the church, farmland, a mill, salt pans and a fishery, are 90 villeins and 25 bordars: these numbers can be multiplied four or five times to account for dependents, as they only represent "adult male heads of households".[225][Fn 46]

By the 13th century Reculver parish provided an ecclesiastical benefice of "exceptional wealth",[44] which led to disputes between lay and Church interests.[229] In 1291 the Taxatio of Pope Nicholas IV put the total income due to the rector and vicar of Reculver at about £130.[230][Fn 47] Included in the parish were chapels of ease at St Nicholas-at-Wade and All Saints, both on the Isle of Thanet, and at Hoath and Herne.[229]

The parish was broken up in 1310 by Robert Winchelsey, archbishop of Canterbury from 1294 to 1313, who created parishes from Reculver's chapelries at Herne and, on the Isle of Thanet, St Nicholas-at-Wade and All Saints, in response to the difficulties posed by the distance between them and their mother church at Reculver, and a "steady increase in population".[232][Fn 48] At this time All Saints became part of St Nicholas-at-Wade parish, and its church was later demolished.[233] However, Reculver continued to receive payments from the parishes of Herne and St Nicholas-at-Wade in the 19th century as a "token of subjection to Reculver",[234] as well as for the repair of Reculver church, and it retained a perpetual curacy at Hoath.[122]

The church building was considerably enlarged over time: the outer walls of the porticus were extended to enclose the nave in the 8th century, forming a series of rooms, including chapels on both northern and southern sides, and a porch across the western side; the towers were added as part of an extension with a new west front in the late 12th century, when the internal walls of the porticus were demolished, creating aisles on the north and south sides of the nave; the original apse was demolished and the chancel more than doubled in size, incorporating a triple east window with columns of Purbeck marble, in the 13th century; and north and south porches were added to the nave in the 15th century.[235][Fn 49] The towers were topped with spires by 1414, since they are shown in an illustrated map drawn by Thomas Elmham in or before that year, and one of the towers held a ring of bells.[236][Fn 50] The addition of the towers, and the extent to which the church was enlarged in the Middle Ages, suggest that "a thriving township must have developed nearby."[240] However, the church retained many prominent Anglo-Saxon features, and, on a visit to Reculver in 1540, one of these raised John Leland to "an enthusiasm which he seldom displayed":[241]

Yn the enteryng of the quyer ys one of the fayrest and the most auncyent crosse that ever I saw, a ix footes, as I ges, yn highte. It standeth lyke a fayr columne. The base greate stone ys not wrought. The second stone being rownd hath curiously wrought and paynted the images of Christ, Peter, Paule, John and James, as I remember. Christ sayeth [I am the Alpha and the Omega]. Peter sayeth, [You are Christ, son of the living God]. The saing of the other iij when painted [was in Roman capitals] but now obliterated. The second stone is of the Passion. The third conteineth the xii Apostles. The iiii hath the image of Christ hanging and fastened with iiii nayles and [a support beneath the feet]. the hiest part of the pyller hath the figure of a crosse.

— John Leland, "Itinerary", 1640[53]

This cross had been removed from the church by 1784.[243][Fn 51] In 1927 archaeologists discovered what was believed to be the base of a 7th–century cross,[245] and it has been suggested that the monastery at Reculver was originally built around this cross.[246] The Reculver cross has been compared with the Anglo-Saxon Ruthwell Cross – an open-air preaching cross in Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland[247] – and traces of paint on fragments of the Reculver cross show that its details were once multicoloured.[248] Later, stylistic assessments indicate that the cross, carved from a re-used Roman column, probably dates from the 8th century or the 9th, and that the stone believed to have been the base may have been the original, 7th-century altar.[249][Fn 52] In 1787 John Pridden observed that the roofline of the nave must have been lowered at some time, judging by the tops of the east and west walls, and the fact that the tops of the two windows over the west door were at that time filled in with brick: he also noted that the roof had been repaired in 1775 by churchwarden A. Sayer, these details appearing embossed on replacement lead.[251]

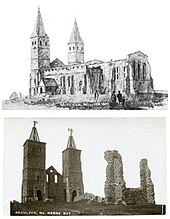

In its final form, the church consisted of a nave 67 feet (20.4 m) long by 24 feet (7.3 m) wide, with north and south aisles of the same length and 11 feet (3.4 m) wide, and a chancel 46 feet (14 m) long by 23 feet (7 m) wide. Including the spires, the towers were 106 feet (32.3 m) high, the towers alone, which survive, reaching 63 feet (19.2 m). The towers measure 12 feet (3.7 m) square internally, and are connected internally by a gallery which was about 25 feet (7.6 m) above the floor of the nave. The full length of the church, east to west, was 120 feet (36.6 m), and the breadth of the west front, which also survives, is 64 feet (19.5 m).[252]

No other buildings belonging to the monastery have been found by archaeologists, but they may all have been in the area to the north of the church, which has been lost to the sea.[253] A building which stood west-northwest of the church may have had an Anglo-Saxon doorway and the dimensions of an Anglo-Saxon church, and had "the appearance of having been part of some monastic erection".[254] It was demolished after the sea weakened its foundations during storms in the winter of 1782.[255] Leland reported another building outside the churchyard, where it was believed that a parish church had stood while the main church at Reculver was still a monastery:[53] this building, formerly a chapel dedicated to St James, was later known as the "chapel-house", and stood in the north-eastern corner of the fort until it collapsed into the sea on 13 October 1802.[256][Fn 53]

This period of destruction culminated in the demolition of almost all of the church of St Mary itself. In the autumn of 1807 a northerly storm combined with a high tide brought erosion of the cliff on which the church stood to within the churchyard, destroying "ten yards [9.1 m] of the wall around the churchyard, not ten yards from the foundation of the church".[258] Sea defences had been in place since at least 1783 but, although they had been costly to build, their design had led to further undermining of the cliff.[259] Two further schemes were devised by Sir Thomas Page and John Rennie to preserve the cliff by means of new sea defences, Rennie's being estimated to cost £8,277.[75] Instead, at a vestry meeting on 12 January 1808, and at the instigation of the vicar, Christopher Naylor, it was decided that the church should be demolished.[260][Fn 54] The decision was reached by vote among eight of the leading residents of Reculver and Hoath, including the vicar: the votes were evenly split, so the vicar used his casting vote in favour of demolition.[262][Fn 55] This was begun in September 1809 using gunpowder, in what has been described as "an act of vandalism for which there can be few parallels even in the blackest records of the nineteenth century":[263][Fn 17]

the young clergyman of the parish, urged on by his Philistine mother, rashly besought his parishioners to demolish this shrine of early Christendom. This they duly did and all save the western towers, which still act as a landmark for shipping, was razed to the ground.

— Nigel & Mary Kerr, A Guide to Anglo-Saxon Sites, 1982[169]

The demolition of this "shrine of early Christendom", and exemplar of Anglo-Saxon church architecture and sculpture,[195][Fn 56] was otherwise thorough, and it is now represented only by the ruins on the site, material incorporated into a replacement parish church at Hillborough,[264] fragments of the cross, and the two stone columns which had been part of the church's triple arch. The columns and fragments of the cross are on display in Canterbury Cathedral.[96][Fn 57] Two thousand tons of stone from the demolished church were sold and incorporated into the harbour wall at Margate, known as Margate Pier, which was completed in 1815, and more than 40 tons of lead was stripped from the church and sold for £900.[265][Fn 58] Trinity House bought what was left of the structure from the parish for £100, to ensure that the towers were preserved as a navigational aid, and built the first groynes, designed to protect the cliff on which the ruins stand.[82] The spires were both destroyed by storms by 1819, when Trinity House replaced them with similarly shaped, open structures, topped by wind vanes.[268][Fn 59] These structures remained until they were removed some time after 1928.[242] The ruins of the church, and the site of the Roman fort within which it was built, are now in the care of English Heritage,[269] and the sea defences protecting the church continue to be maintained by Trinity House.[270]

The twin towers and west front of St John's Cathedral, Parramatta, in Sydney, Australia, which were added in 1817–1819, are based on those of the church at Reculver.[271] Efforts to save Reculver church were still under way when Governor Lachlan Macquarie and his wife Elizabeth had left England for Australia in 1809; Elizabeth Macquarie asked John Watts, the governor's aide-de-camp from 1814 to 1819, to design the towers:

Mrs Elizabeth Macquarie showed Lieutenant John Watts, Aide De Camp of the 46th Regiment a watercolour of the church and asked him to design some towers for [St John's, Parramatta]. A watercolour of Reculver Church in the [Mitchell Library section of the State Library of New South Wales] has a note in Macquarie's hand that he laid the foundation stone on 23 December 1818. Mrs Macquarie chose the plan and Lt. Watts was responsible for implementing the design ...

In 1990 a stone from Reculver was presented to St John's Cathedral by the Historic Building and Monuments Commission for England, now English Heritage.[273]

Country park

Reculver Country Park is a Special Protection Area (SPA), Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) and Ramsar site, due partly to the birds that visit Reculver each year during their migrations from the Arctic, and is managed by Canterbury City Council and the Kent Wildlife Trust.[274] It comprises a narrow strip of protected, cliff-top land about 1.5 miles (2 km) long, running from the remaining enclosure of the Roman fort and the church ruins west to Bishopstone Glen. In winter Brent Geese and wading birds such as Sanderlings and Turnstones may be seen, during the summer months the largest colony of Sand Martins in Kent nest in the soft cliffs, on top of which Fulmars were also reported to have begun nesting in 2013, and wading Curlews may be seen at any time.[275] The grasslands on the cliff top are among the few remaining cliff top wildflower meadows left in Kent, and are home to butterflies and Skylarks. Also present is the nationally scarce species of digger wasp Alysson lunicornis.[276][Fn 61] The park first won a Green Flag Award in 2005, and it is estimated that over 200,000 people visit it each year, including up to 3,500 students for educational trips.[277] Canterbury City Council's Reculver Masterplan envisages purchasing farmland to the south of the country park to replace land lost to the sea through coastal erosion.[278]

In 2011 it was found that the shoreline in the Herne Bay area, including Reculver, had come under threat from an invasive species, the Carpet sea squirt (Didemnum vexillum), also known as "marine vomit".[279] First recorded in UK waters in 2008, the Carpet sea squirt is indigenous to the sea around Japan, but it has been carried to other parts of the world, including New Zealand and the USA, on boat hulls, fishing equipment, and floating seaweed.[280] Carpet sea squirt can overgrow other, sessile species, "potentially smothering species living in gravel and affecting fisheries."[280][Fn 62]

Centre for renewable energy

A visitor centre in Reculver Country Park re-opened in 2009 as the Reculver Renewable Energy and Interpretation Centre, "marking 200 years of the moving of Reculver village".[281][Fn 63] The centre features a log burner fuelled by logs from the Blean woodland, solar and photovoltaic panels provide electrical power for the centre, and it has displays and information describing the history, geography and wildlife of the area.[281]

Transport

Reculver is at the end of an unclassified road, Reculver Lane, and is about 2 miles (3.2 km) by road from the nearest major junction of the A299, or "Thanet Way". From Roman times Reculver was connected to Canterbury by a road, the presence of which is reflected in parish boundaries for much of its length.[287][Fn 64] An estate map of 1685 shows the Reculver end of this road as "The King's highe Way", which may have been in use until 1875, when it was reported that a public road had been diverted because of a cliff fall near Love Street Farm.[289][Fn 65] Remains of a Roman road leading to the east gate of the fort have also been found, which were "substantial ... consisting of a sandstone platform [10–13 feet (3–4 m)] wide and at least [11 inches (30 cm)] deep."[290]

In 1817 the nearest coaching route to Reculver was that running between London, Canterbury and the Isle of Thanet, which passed through Upstreet, about 4 miles (6.4 km) south of Reculver, before entering Thanet.[291] In 1839 coaches and vans ran daily from Herne Bay to Canterbury and on to destinations on the southern and eastern coasts of Kent, with access to the English Channel, at Deal, Dover, Sandgate and Hythe.[292] In 1865 transport between Herne Bay and Reculver was available by "fly" – a type of one-horse hackney carriage.[293]

As of 2014 a bus service, route 7/7A, connects Reculver directly with Herne Bay and Canterbury daily except Sundays and bank holidays.[294] Other destinations on this route include Reculver Church of England Primary School at Hillborough, Broomfield, Chislet, Hoath and the railway station at Sturry, on the Ashford to Ramsgate line. Route 36 connects Reculver with Herne Bay and Margate daily except Sundays.[295] Other destinations on this route include Reculver Church of England Primary School at Hillborough, Beltinge, Birchington-on-Sea and Westgate-on-Sea. The bus stop at Reculver is adjacent to the King Ethelbert Inn.

The nearest railway stations to Reculver are at Herne Bay, about 3.8 miles (6.1 km) to the west, and Birchington-on-Sea, about 4.5 miles (7.2 km) to the east. Both stations are on the Chatham Main Line, running between London's Victoria station and Ramsgate, on the south-eastern coast of the Isle of Thanet.[296] The railway first reached Herne Bay from the west in 1861 and was extended to Ramsgate Harbour railway station by 1863, but no provision was made for public access from Reculver, although purchase of land for a station there had been envisaged and a short-lived goods station for Reculver was opened in 1864.[297] In the same year a passenger station was proposed for Reculver, primarily to serve tourists, but it was not built.[298] In 1884 the South Eastern Railway proposed building a branch line from its station at Grove Ferry on the Ashford to Ramsgate line to join the London, Chatham and Dover Railway's Chatham Main Line at Reculver, thereby linking Canterbury and Herne Bay.[299] The Canterbury and Kent Coast Railway Bill was presented to a select committee of MPs in January 1885: the London, Chatham and Dover Railway objected to it, particularly the junction with their main line at Reculver, so the Bill was rejected and the line was not built.[300] Rudimentary houses were erected by the East Kent Railway company on marshland near Reculver in 1858 for the navvies who constructed the line through the area; these had been taken over by enginemen of the South Eastern and Chatham Railway by October 1904, when they were replaced by cottages.[301]

There is no formal access to Reculver by sea, but Reculver has had connections with the sea since the 1st century, when the Roman fort of Regulbium had a supporting harbour.[19] The quantity and variety of coins found at Reculver dating from the 7th century to the 8th are almost certainly related to its location on a major trade route through the Wantsum Channel.[28] Anglo-Saxon Reculver probably had its own harbour, and the monastery at Reculver may well have operated a "fleet of ships and its own boatyard."[302] Details in the 10th-century charter in which King Eadred gave Reculver to the archbishops of Canterbury suggest that there was then an island north of Reculver, with its own "mini-Wantsum [Channel, which] could have provided a sheltered channel for beaching and berthing ships";[303] the present day Black Rock beyond the shoreline at Reculver may be a remnant of this island.[304]

In the 16th century, oysters dredged at Reculver were reported as better than any in Kent,[167] and, in the 17th century, an inlet north-west of Reculver was described as "anciently for a harber of ships, called now The Old Pen".[305] In the 18th century there was a place for landing passengers and goods at Reculver village.[306] The former name of the King Ethelbert Inn at Reculver, the "Hoy and Anchor", makes reference to hoys, a local type of merchant sailing vessel,[36] which continued to serve the coastline around Reculver in the mid-19th century, by which time the remnant of the village had been recorded as home only to "fishermen and smugglers".[307] In 1810 a canal was proposed to run from the coast between Reculver and St Nicholas-at-Wade to Canterbury, with a harbour for sea-going vessels at the northern end, which would be accessible from Reculver by a new road to begin at the inn, but none of this was built.[308][Fn 66] Passenger steamships called at Herne Bay pier on their route between London and destinations along the north coast of Kent from 1832, but this service ceased in 1862.[310] A travel guide of 1865 advised that

[the] best way to visit Reculver from Margate is by means of a sailing or rowing boat ... [although] Herne Bay is by far the most convenient place to get to Reculver from, as you can be rowed to the foot of the twin towers in little more than half an hour ... [after which] we run the boat on the beach, and plant our foot on the famous "Rutupian shore," sung by Juvenal ...

— All About Margate and Herne Bay, 1865[311]

Coastguards were stationed at Reculver from the mid-19th century until they were withdrawn in the mid-20th century,[312] but the towers of the ruined church of Reculver remain a landmark for mariners, both practically and through their use to mark the division between areas covered by Thames Maritime Rescue Coordination Centre (MRCC) and Dover MRCC.[313]

Education

Reculver Church of England Primary School is adjacent to the church at Hillborough, in Reculver parish, where Reculver residents relocated in the late 18th century and early 19th century due to coastal erosion.[314] In 2006 the school was ranked above both the local and national averages in most criteria,[315] but it was rated as "satisfactory" (Grade 3) in most aspects by an Ofsted report in July 2010, when it had 489 pupils.[316] In a Section 8 report,[317] released in November 2011, remedial progress at the school was described as "satisfactory".[318] After a school inspection report was released in March 2013, the school was placed under "special measures", meaning that it was "failing to give its pupils an acceptable standard of education, and the persons responsible for leading, managing or governing the school [were] not demonstrating the capacity to secure the necessary improvement in the school";[319] but a further Section 8 report of November 2013 described the school as making "reasonable progress towards the removal of special measures."[320] As of 10 March 2014, when the school had 466 pupils, 100% of the 71 pupils who were eligible for Key Stage 2 assessment achieved level 4 or above in reading, writing and arithmetic; for the school as a whole this figure was 61%, whereas the English national average was 75%.[321] The school's site also hosts Beltinge Day Nursery and Reculver Breakfast and Afterschool Club.[322] The nearest school for older children is Herne Bay High School.[323]

Religion

A new Anglican parish church for Reculver was built at Hillborough, about 1.25 miles (2 km) south-west of Reculver, but within Reculver parish, as a replacement for the old church of St Mary the Virgin at Reculver.[324] The new church was given the same dedication as the old one, to St Mary the Virgin, and, standing on a plot of land bought for £30, it was consecrated on 13 April 1813.[325] A "miserable little [church] ... built in a rough and poverty-stricken style",[324] it was already decaying in 1874 and was replaced by the present structure, begun in 1876 and consecrated on 12 June 1878.[326]

The church begun in 1876 was built by Gothic Revival architect Joseph Clarke,[327] who was surveyor for the diocese of Canterbury at the time.[328] It has seating for about 100 people, and is a "simple and relatively plain building",[329] though it incorporates stonework from the old church at Reculver.[264][Fn 67] The medieval baptismal font in the church is probably from the former chapel of All Saints, Shuart, on the Isle of Thanet, which was demolished in the 15th century.[330][Fn 68] A war memorial stands at the edge of the churchyard, facing into the adjacent Reculver Lane, and records the names of 27 parishioners who died fighting in the First World War and the Second World War.[332]

Notable people

King Eadberht II of Kent was buried in the church at Reculver in the 760s.[212][Fn 42] His tomb was in the south porticus of the church, adjacent to the chancel, though this later became part of the church's south aisle.[214][Fn 69] This was traditionally believed to be the tomb of King Æthelberht I of Kent,[333] and was "of an antique form, mounted with two spires".[34][Fn 70] Simon of Faversham, a 14th-century philosopher and theologian, was appointed rector of Reculver but was forced to defend his appointment to the pope, and died in France, either on his way to the papal curia in Avignon or after his arrival, some time before 19 July 1306.[335]

The first recorded owner of Brook, about 0.8 miles (1 km) south-southwest of Reculver, but within Reculver parish, was Nicholas Tingewick,[337] physician to King Edward I and rector of Reculver until 1310, when he became its first recorded vicar.[338] He was regarded as the "best doctor for the king's health",[339] and there are more records of his medical practice than there are for "most physicians of his time."[339] Brook subsequently passed to James de la Pine, sheriff of Kent in the early 1350s.[340][Fn 71] His grandson sold it to an ancestor of Henry Cheyne,[342] who was elected knight of the shire for Kent in 1563, and was created "Lord Cheyney" in 1572.[343] He had sold all of his possessions in Kent by 1574 to "finance his extravagance",[343] and Brook subsequently became the property of Sir Cavalliero Maycote, who was a leading courtier to Elizabeth I and James I.[342] He had a "handsome monument [in the church at Reculver] representing Sir Cavalliero and Lady Maycote, with their eight children, all in alabaster figures, kneeling".[243][Fn 72] Brook is now Brook Farm, where there is a remnant of Maycote's home in the form of a gateway, which is a "very rustic Elizabethan affair",[327] all of brick, with mouldings.[347][Fn 73]

Thomas Broke, alderman and MP for Calais in the mid-16th century,[349] may have been a son of Thomas Brooke of Reculver, as well as being a "religious radical".[350] Ralph Brooke, officer of arms as Rouge Croix Pursuivant and York Herald under Elizabeth I and James I, died in 1625 and was buried in the church at Reculver, where he was commemorated by a black marble tablet on the wall of the chancel, showing him dressed in his herald's coat.[351][Fn 74]

Robert Hunt, vicar of Reculver from 1595 to 1602, became minister of religion to the English colonial settlement at Jamestown, Virginia, sailing there in the ship Susan Constant in 1606, and probably celebrated "the first known service of holy communion in what is today the United States of America on 21 June 1607."[353] Barnabas Knell was vicar of Reculver from 1602 to 1646: during the English Civil War his son Paul Knell, born in about 1615, was chaplain to a regiment of Royalist cuirassiers, to whom he preached a sermon, "The convoy of a Christian", at the siege of Gloucester in August 1643.[354][Fn 75] An estate map of 1685 shows that much of Reculver then belonged to James Oxenden, who spent much of his life as an MP for Kent constituencies, between 1679 and 1702.[356]

References

Footnotes

- ^ "Many more [Old English] forms are on record."[4]

- ^ The reconstructed plaque mentions the basilica and an aedes principiorum, for which sacellum, or "headquarters shrine", is understood.[12]

- ^ A strigil, which would have been used in the bath house, was found on the shore at Reculver some time before 1708, and was described and illustrated by Charles Roach Smith in 1850.[14] A reconstruction of the fort is illustrated at Wilmott 2012, p. 23.

- ^ "The evidence suggests that [most of the Saxon Shore forts] were constructed c. 225-290, and this means that the system was conceived about sixty years before the historical records refer to Germanic raiding. The discrepancy cannot be explained if they were a purpose-built defensive system, but it can be explained if they were a series of state trans-shipment centres."[21]

- ^ "[A] Roman building with a hypocaust and [mosaic floor] stood considerably to the northward of the fort".[23]

- ^ While "[it] must be certain that the Roman fort had a supporting harbour, probably a natural feature improved by quays and jetties",[19] "[the] quantity of seventh- and eighth-century coins picked up from Reculver and its vicinity is paralleled [in England] only at Hamwic [Anglo-Saxon Southampton]: finds include gold thrymsas and some 50 sceattas, with contemporary Merovingian coins and a small group of Northumbrian issues. ... Almost certainly there is some connection with Reculver's position on a major trading route".[28]

- ^ "[The Reculver fibula] belongs to a class of ornaments ... remarkable for peculiarities which seem almost to restrict them to the early Kentish Saxons. [John] Battely speaks of the fibulæ found at Reculver [in the late 17th and early 18th centuries], as being almost innumerable; some of these ... were constructed with much artistic skill and good workmanship; they were either enameled, or set with precious stones."[30]

- ^ The Roman remains at Reculver would have been "the only substantial building for miles around",[36] but "Anglo-Saxon kings seem to have shown little interest in establishing themselves in old Roman forts."[28] "An itinerant royal household eating and drinking the food surpluses collected at [the king's] own estates and those of his subjects ... lies at the core of the Kentish kingdom ..."[37]

- ^ Hasted 1800 refers to Reculver as a "borough",[34] but it is not listed as an ancient borough in Beresford, M. & Finberg, H.P.R., English Medieval Boroughs A Hand-List, David & Charles, 1973. However, tithings in Kent were known as "borghs", a word cognate with "borough", but derived from "borh", a "pledge".[47]

- ^ The taxpayers of Hoath were presumably included with those of Reculver, since Hoath is not listed separately.[50] An estimated 5% of the English population were exempt from or evaded the poll tax of 1377.[51]

- ^ "Even so it was stipulated that the arches had to be big enough for boats and lighters to pass, in the hope that ‘the water shall happen to increase’".[58] A late-15th century note in the archives of Canterbury Cathedral states that "[r]ecently the channel has become so silted up that the ferry can no longer cross it, except for an hour during the high spring tides."[59]

- ^ Part of this map is illustrated in Dowker 1878a, facing page 8.

- ^ Writing in 1787, John Pridden described the only fare available at Reculver as "dry biscuit, bad ale, sour cheese, or weak moonshine".[65]

- ^ In 1821 Reculver was described as a principal station for the "Smuggling Preventive Service".[69] Records of the coast's erosion between about 1540 and 1800 are represented graphically at Gough 2002, p. 205.

- ^ After a very low tide in 1784, a writer to The Gentleman's Magazine reported that, "the Black Rock (as it is called) being left dry, the foundations of the ancient parish church were discovered, which had not been seen for 40 years before."[70]

- ^ The farmers sold the "sea side stone work ... to the Margate pieor Compney for a foundation for the new pier and the timber by [auction] as It was good oak fit for their [own] use".[72] An advertisement in the Kentish Gazette, Tuesday 7 July 1807, announced that "about 300 sound oak posts" were to be auctioned at Reculver on 16 July by order of the Commissioners for Sewers.[73] A similar advertisement of 12 July 1808 announced an auction of "oak post, and ... a quantity of large stone".[74]

- ^ a b Some sources date the church's demolition to 1805,[77] but a meeting to discuss the church's future was held at the church on 12 January 1808;[78] a detailed description of the standing church, including pleas for its preservation, was submitted to The Gentleman's Magazine on 3 March 1809;[79] The Gentleman's Magazine reported in 1809 and 1856 that the church's demolition began in September 1809;[80] and the year of the church's demolition is given as 1809 in the archive of Canterbury Cathedral.[81]

- ^ In a letter written in March 1809 to The Gentleman's Magazine, but published in September, T. Mot wrote that the vicarage was "one of the most mean structures ever appropriated to such a purpose".[83] Another letter to the same magazine described the vicarage as follows: "[It has] the appearance of some antiquity; it consists of two miserable rooms on the ground floor and a like number above, with no other conveniences or appurtenances of any kind. In fact was it not for the stone porch with which the entrance is decorated, it would pass only for the cottage of a labourer."[36]

- ^ T. Mot's letter in The Gentleman's Magazine ends with the observation that the "jolly landlord revelled with his noisy guests, where late the venerable Vicar smoked his lonely pipe."[83] Another correspondent writing to the same magazine in 1856 reported that this "desecration did not prosper. According to the testimony of some of the present inhabitants of Reculver, nothing went well with the publican: his family was perpetually disturbed by strange noises and pranks ... and he was eventually obliged to retire, a ruined man."[86]

- ^ "On the entrance door [of the King Ethelbert Inn] are the words 'Hoy and Anchor Bar'".[36] The sign for the Hoy and Anchor Inn was reported as hanging in the King Ethelbert Inn in 1871,[89] and as being in the Herne Bay Club in 1911.[90] The existence of two other public houses at Reculver was reported at different times in the 19th century, namely the Cliff Cottage in 1869,[91] and the Pig and Whistle in 1883.[92]

- ^ The King Ethelbert public house has protected status as a locally listed building.[93]

- ^ Reculver is listed as a "possible deserted medieval village" (DMV) in the Kent Historic Environment Record.[94]

- ^ References such as "S 546" indicate the number given to an Anglo-Saxon charter in Sawyer 1968. Details, Latin texts and English translations of charters referenced by Sawyer number in this article can be found through the list at The Electronic Sawyer (2014). "Browsing charters". King's College London. Retrieved 20 April 2014. A map of the mainland part of the estate is at Gough 1992, Fig. 10.

- ^ Bleangate is about 1.25 miles (2 km) south-west of Herne, at OS grid reference TR167645. In 1274–75 the jury for Bleangate hundred said that half of the hundred was in the hands of the Archbishop of Canterbury, and the other half was in the hands of the Abbot of St Augustine's, but that "they [did] not know from what time".[108] Bleangate hundred seems to have been in existence at the time of Domesday Book although not referenced by it, and if so probably included the Domesday hundreds of Chislet, Sturry and Reculver in 1086 as it did in the 13th century.[109]

- ^ All the members of Bleangate hundred were assessed at the same rate of £12.14s. (£12.70) for the two fifteenths and tenths granted to Elizabeth I in 1571 except for Herne, which was assessed at £12.15s (£12.75).[111] While Sarre on the Isle of Thanet had been included in Bleangate hundred in 1274–75, by 1540 it was in Ringslow hundred, which consisted entirely of places on the Isle of Thanet.[112]

- ^ The election of a "Constable of the Half Hundred of Bleangate" named Cob as sidesman for Reculver church was reported in 1596: he refused this duty on the grounds that he was too busy in his role as constable, and was supported in this claim by a letter from the "Worshipful" Mr Peter Manwood.[116] In 1835 the court baron was also held at Herne.[117]

- ^ For the historical parish boundary see Vision of Britain (2009). "Reculver AP/CP". University of Portsmouth et al. Boundary Map of Reculver AP/CP. Retrieved 20 April 2014. For the current ecclesiastical parish boundary, see achurchnearyou.com (2014). "Parish Boundary (06BLK121)". Google Maps. Retrieved 20 April 2014.

- ^ Caroline Lucas gave up her role as MEP in 2010, when she was elected as the UK's first Green Party MP, for Brighton Pavilion.[130]

- ^ Philp 2005, Fig. 4, shows a conjectured Roman coastline around Reculver, where the fort is located near the root of a promontory projecting about 1.25 miles (2 km) north-eastwards into the sea. This promontory is defined on its north-western side by a long inlet of the sea, and on its south-eastern side by the Wantsum Channel, and is made a peninsula by an inlet of the Wantsum Channel just south of the Roman fort.

- ^ "[A]longshore transport rates are low [between Bishopstone Glen and Reculver]. Apart from along the eastern end of the section where there is a weak east to west transport, there does not appear to be a strong drift in either direction."[143]

- ^ The increase in numbers in the early 20th century may be partly due to holidaymakers, who were included in census returns: while the postcard image from 1913 shows that there was sufficient tourism by then to support a cafe, the census of 2001, undertaken on 29 April, albeit covering a smaller area than the earliest censuses, records almost a quarter (32) of the 135 people in the Reculver area as being in a "Caravan or other mobile or temporary structure".[155]

- ^ William Lambarde, writing in 1576, gave the day of the fair as "7.Septemb. being the Nativitie of the blessed virgine Marie",[162] to whom the church at Reculver was dedicated.

- ^ "Shortly after World War II a caravan site was established below the church which has since grown so large that much imagination is now required to conjure up the majesty of its former setting."[169] A 1953 image of the ruins at Reculver surrounded by caravans is at Canterbury City Council 2008, p. 7.

- ^ A travel guide of 1865 described "the Ethelbert's Arms" as "a quaint little hostelry, where the visitor will meet with perhaps rude fare, but with certainly the most civil attention."[170]

- ^ "Reculver’s role in the region wide development of East Kent as a green tourism destination is central to [Natural East Kent]’s work. The objective is to create access to good connections across the region for walkers and cyclists, to provide good interpretation of natural and heritage assets and to support the private sector to provide good quality accommodation."[172]

- ^ The byname is also found as "The Sisters" and the "Two Sisters", but the towers are also sometimes known as simply "The Reculvers".[177]

- ^ "The Romans officially condemned human sacrifice ... Human life was cheap on the frontier, however, and Roman auxiliaries could be as barbarous as those they fought. ... Even in the most civilised parts of [Roman] Britain, the authorities seem on occasion to have turned a blind eye to infant sacrifice, which may of course have been surreptitious."[182]

- ^ According to Hasted 1800, King Ecgberht gave Reculver for the establishment of a monastery "as an atonement for the murder of his two nephews [sons of Eormenred of Kent]",[34] but Kelly 2008 makes no mention of this, instead placing the monastery's establishment in the context of domination of the early Kentish church by "non-native" leaders and observing that "[perhaps] it is no coincidence that in the year of Theodore's arrival [from Rome] King Ecgberht was involved in the establishment of a house of male religious [at Reculver] in a strategic location outside Canterbury. ... It may be significant that the next archbishop after the death of Theodore in 690 was Berhtwald, abbot of Reculver by 679 and perhaps Bassa's immediate successor."[192] John Blair suggests that Reculver's foundation may have been prompted by Wilfrid.[193] Hussey 1852, p. 135, regards Bassa the priest, who founded the church at Reculver in 669, as identical with the Northumbrian warrior Bassus who, according to Bede, had accompanied Paulinus of York and Æthelburh of Kent to Kent after the death of her husband King Edwin of Northumbria: this occurred 33 years before the foundation of the monastery at Reculver, in 633.[194]

- ^ The columns were "Saxon rather than Roman."[198] An English Heritage information plaque for visitors to the site of the church, headed "An Anglo-Saxon Church", shows a reconstruction of the original church of Reculver, with monks robed in black in the chancel;[199] a similar image is at Wilmott 2012, p. 24. Triple arches also featured in near-contemporary churches at St Augustine's Abbey (Canterbury), Bradwell and Lyminge.[200]

- ^ The inclusion of porticus at Reculver in the 7th century was described in 1965 as being "without parallel in western Europe,"[201] except among contemporary churches in Kent and at Bradwell, in Essex,[202] but more recent analysis has shown that porticus were probably more common in early Anglo-Saxon churches.[200]

- ^ S 8 is the earliest genuine Anglo-Saxon charter known to have survived in its original form.[206] "Sarre was a highly strategic place, overlooking the confluence of the Wantsum and the Great Stour, directly linked to Canterbury ... In the early 760s it was the site of a toll-station, where the agents of the Kentish kings collected dues on trading ships using the Wantsum route ... but its importance goes back much earlier ... and it may be that the [church at Reculver] received a share of the royal tolls levied at Sarre."[205]

- ^ a b In her 2004 entry for Æthelberht II in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Susan Kelly wrote that Eadberht I of Kent was buried at Reculver "in 748".[213] However, in Kelly 2008, she observes that there is "a much better context"[214] for this royal burial to have been of Eadberht II, who "faded from view c. 763 x 764".[212] The royal tomb at Reculver was "in a position corresponding to the south porticus (at St Augustine's kings were buried in the south porticus); an inscription or other record identifying [the occupant] as King Eadberht (grand-)son of King Æthelberht may have given rise to the later belief that it was the earlier King Æthelberht himself that was buried [at Reculver]."[212]

- ^ The text of this charter, with an English translation, is online at The Electronic Sawyer (2014). "S 546". King's College London. Retrieved 20 April 2014. See also Gough 1992 and Brooks 1989, p. 72. The land at Chilmington was "probably a recent gift to the church."[42]

- ^ The abbot and monastic community of Reculver "may have been given a refuge [from the Vikings] within Canterbury, as were the abbess and community at Lyminge as early as 804 (S 160)."[218] "Indeed, if [other Kentish] minsters' [post-Viking] monopoly on archiepiscopal chrism is really a survival from the seventh century, the Eastern Kentish church preserved its primary ... character against all the odds",[220] though, by the eleventh century, Reculver seems to have "dropped out of sight entirely".[221]

- ^ Of the £42.7s. from Reculver, £7.7s. (£7.35) was from an unspecified source. While Hoath, Herne and western parts of the Isle of Thanet were Reculver possessions in the Anglo-Saxon period, and remained attached to Reculver long after 1086, of these only Reculver is mentioned by name in Domesday Book: "[as] the name [Reculver] is used here, it means something larger than the parish but much smaller than the thirteenth-century manor of Reculver. It is fairly sure to have included Hoath ...; it may also have included the adjoining part of Thanet, [including] All Saints ... and St Nicholas-at-Wade ... [The separate manor of Nortone is] Herne ... under another name."[104]

- ^ The multiplication indicated by Eales would give a peasant population for the whole of the estate centred on Reculver in 1086 of 460–575 people. The mill was probably a watermill, near Brook Farm, and King Eadred's charter of 949 mentions a "mill-creek" in the area.[226] There are numerous medieval salt working sites in the area to the south and east of Reculver, many of which lie on land belonging to Reculver in the medieval period, for example at TR23316797.[227]

- ^ From 1310, the rector of Reculver was the archbishop of Canterbury.[231]

- ^ In 1274–75, the jurors of Bleangate hundred, in which Reculver then lay, reported that it had lately been made more difficult for the people of Thanet to reach the mainland: while previously access had been provided by a "wall", this had been cut off by a ditch dug for the abbot of St Augustine's, Canterbury.[108]