Ariel Sharon

Ariel Sharon אריאל שרון | |

|---|---|

Sharon speaking as Israeli Foreign Minister in the United States, 1998 | |

| 11th Prime Minister of Israel | |

| In office March 7, 2001 – April 14, 2006* | |

| President | Moshe Katsav |

| Deputy | Ehud Olmert |

| Preceded by | Ehud Barak |

| Succeeded by | Ehud Olmert |

| Minister of Foreign Affairs | |

| In office October 13, 1998 – June 6, 1999 | |

| Prime Minister | Benjamin Netanyahu |

| Preceded by | David Levy |

| Succeeded by | David Levy |

| Minister of Energy and Water Resources | |

| In office July 8, 1996 – July 6, 1999 | |

| Prime Minister | Benjamin Netanyahu |

| Preceded by | Yitzhak Levy |

| Succeeded by | Eli Suissa |

| Minister of Housing and Construction | |

| In office June 11, 1990 – July 13, 1992 | |

| Prime Minister | Yitzhak Shamir |

| Preceded by | David Levy |

| Succeeded by | Binyamin Ben-Eliezer |

| Minister of Industry, Trade and Labour | |

| In office September 13, 1984 – February 20, 1990 | |

| Prime Minister | Shimon Peres (1984–86) Yitzhak Shamir (1986–90) |

| Preceded by | Gideon Patt |

| Succeeded by | Moshe Nissim |

| Minister of Defense | |

| In office August 5, 1981 – February 14, 1983 | |

| Prime Minister | Menachem Begin |

| Preceded by | Menachem Begin |

| Succeeded by | Menachem Begin |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Ariel Scheinermann February 26, 1928 Kfar Malal, British Palestine |

| Died | January 11, 2014 (aged 85) Ramat Gan, Israel |

| Political party | Likud (1973–1977) Shlomtzion (1977) Likud (1977–2005) Kadima (2005–2006) |

| Spouse(s) | Margalit Sharon (d. 1962); Lily Sharon (d. 2000) |

| Children | 3 |

| Alma mater | Hebrew University of Jerusalem Tel Aviv University |

| Profession | Military officer |

| Signature |  |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1948–74 |

| Rank | |

| Unit | Paratroopers Brigade Unit 101 Golani Brigade |

| Commands | Southern Command Paratroopers Brigade Unit 101 Golani Brigade |

| Battles/wars | Israeli Independence War Suez Crisis Six-Day War Yom Kippur War |

| |

Ariel Sharon (Hebrew: , Arabic: أرئيل شارون, Ariʼēl Sharōn, also known by his diminutive Arik, אַריק, born Ariel Scheinermann, אריאל שיינרמן; February 26, 1928 – January 11, 2014) was an Israeli politician and general, who served as the 11th Prime Minister of Israel until he was incapacitated by a stroke.[1]

Sharon was a commander in the Israeli Army from its creation in 1948. As a soldier and then an officer, he participated prominently in the 1948 War of Independence, becoming a platoon commander in the Alexandroni Brigade and taking part in many battles, including Operation Ben Nun Alef. He was an instrumental figure in the creation of Unit 101, and the Retribution operations, as well as in the 1956 Suez Crisis, the Six-Day War of 1967, the War of Attrition, and the Yom-Kippur War of 1973. As Minister of Defense, he directed the 1982 Lebanon War.

Sharon was considered the greatest field commander in Israel's history, and one of the country's greatest military strategists.[2] After his assault of the Sinai in the Six-Day War and his encirclement of the Egyptian Third Army in the Yom Kippur War, the Israeli public nicknamed him "The King of Israel".

Upon retirement, Sharon entered politics, joining the Likud, and served in a number of ministerial posts in Likud-led governments from 1977–92 and 1996–99. He became the leader of the Likud in 2000, and served as Israel's prime minister from 2001 to 2006. In 1983 the Kahan Commission, established by the Israeli Government, found that as Minister of Defense during the 1982 Lebanon War Sharon bore "personal responsibility" "for ignoring the danger of bloodshed and revenge" in the massacre by Lebanese militias of Palestinian civilians in the refugee camps of Sabra and Shatila.[3] The Kahan Commission recommended Sharon's removal as Defense Minister, and Sharon did resign after initially refusing to do so.

From the 1970s through to the 1990s, Sharon championed construction of Israeli settlements in the West Bank and Gaza Strip. However, as Prime Minister, in 2004–05 Sharon orchestrated Israel's unilateral disengagement from the Gaza Strip. Facing stiff opposition to this policy within the Likud, in November 2005 he left Likud to form a new party, Kadima. He had been expected to win the next election and was widely interpreted as planning on "clearing Israel out of most of the West Bank", in a series of unilateral withdrawals.[4][5][6] After suffering a stroke on January 4, 2006, Sharon remained in a permanent vegetative state until his death in January 2014,[7][8][9]

Early life

Sharon was born on February 26, 1928 in Kfar Malal, an agricultural moshav, then in the British Mandate of Palestine, to Shmuel Scheinerman (1896–1956) of Brest-Litovsk and Vera (née Schneirov) Scheinerman (1900–1988) of Mogilev.[10] His parents met while at university in Tiflis (now Tbilisi, Republic of Georgia), where Sharon's father was studying agronomy and his mother was studying medicine. His mother, Vera, was from a family of Subbotnik Jewish origin.[11] They immigrated to Mandatory Palestine in 1922 in the wake of the Russian Communist government's growing persecution of Jews in the region.[12]

The family arrived with the Third Aliyah and settled in Kfar Malal, a socialist, secular community.[13] Although they were Mapai supporters, they did not always accept communal consensus: "The Scheinermans' eventual ostracism ... followed the 1933 Arlozorov murder when Dvora and Shmuel refused to endorse the Labor movement's anti-Revisionist calumny and participate in Bolshevic-style public revilement rallies, then the order of the day. Retribution was quick to come. They were expelled from the local health-fund clinic and village synagogue. The cooperative's truck wouldn't make deliveries to their farm nor collect produce."[14]

Four years after their arrival at Kfar Malal, the Sheinermans had a daughter, Yehudit (Dita). Ariel was born two years later. At age 10, he joined the youth movement HaNoar HaOved VeHaLomed. As a teenager, he began to take part in the armed night-patrols of his moshav. In 1942 at the age of 14, Sharon joined the Gadna, a paramilitary youth battalion, and later the Haganah, the underground paramilitary force and the Jewish military precursor to the Israel Defense Forces (IDF).[13]

Military career

Battle for Jerusalem and 1948 War of Independence

Sharon's unit of the Haganah became engaged in serious and continuous combat from the autumn of 1947, with the onset of the Battle for Jerusalem. Without the manpower to hold the roads, his unit took to making offensive hit-and-run raids on Arab forces in the vicinity of Kfar Malal. In units of thirty men, they would hit constantly at Arab villages, bridges and bases, as well as ambush the traffic between Arab villages and bases.

Sharon wrote in his autobiography: "We had become skilled at finding our way in the darkest nights and gradually we built up the strength and endurance these kind of operations required. Under the stress of constant combat we drew closer to one another and began to operate not just as a military unit but almost as a family. ... [W]e were in combat almost every day. Ambushes and battles followed each other until they all seemed to run together."[15]

For his role in a night-raid on Iraqi forces at Bir Adas, Sharon was made a platoon commander in the Alexandroni Brigade.[13] Following the Israeli Declaration of Independence and the onset of the War of Independence, his platoon fended off the Iraqi advance at Kalkiya. Sharon was regarded as a hardened and aggressive soldier, swiftly moving up the ranks during the war. He was shot in the groin, stomach and foot by the Jordanian Arab Legion in the First Battle of Latrun, an unsuccessful attempt to relieve the besieged Jewish community of Jerusalem. Sharon wrote of the casualties in the "horrible battle," and his brigade suffered 139 deaths. After recovering from the wounds received at Latrun, he resumed command of his patrol unit. On December 28, 1948, his platoon attempted to break through an Egyptian stronghold in Iraq-El-Manshia.[citation needed]

At about this time, Israeli founding father David Ben-Gurion gave him the name "Sharon".[16] In September 1949, Sharon was promoted to company commander (of the Golani Brigade's reconnaissance unit) and in 1950 to intelligence officer for Central Command. He then took leave to begin studies in history and Middle Eastern culture at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Sharon's subsequent military career would be characterized by insubordination, aggression and disobedience, but also brilliance as a commander.[17]

Unit 101

A year and a half later, on the direct orders of the Prime Minister, Sharon returned to active service in the rank of major, as the founder and commander of the new Unit 101, a special forces unit tasked with reprisal operations in response to Palestinian fedayeen attacks. The first Israeli commando unit, Unit 101 specialized in offensive guerrilla warfare in enemy countries.[13] The unit consisted of 50 men, mostly former paratroopers and Unit 30 personnel. They were armed with non-standard weapons and tasked with carrying out special reprisals across the state's borders— mainly establishing small unit maneuvers, activation and insertion tactics. Training included engaging enemy forces across Israel's borders.[18] Israeli historian Benny Morris describes Unit 101:[19]

The new recruits began a harsh regimen of day and night training, their orientation and navigation exercises often taking them across the border; encounters with enemy patrols or village watchmen were regarded as the best preparation for the missions that lay ahead. Some commanders, such as Baum and Sharon, deliberately sought firefights.

In retaliation for fedayeen attacks on Israel, Unit 101 undertook a series of raids against Jordan, which then held the West Bank. The raids also helped bolster Israeli morale and convince Arab states that the fledgling nation was capable of long-range military action.[citation needed] Known for raids against Arab civilians and military targets, the unit is held responsible for the widely condemned Qibya massacre in the fall of 1953. After a group of Palestinians used Qibya as a staging point for a fedayeen attack in Yehud that killed a Jewish woman and her two children in Israel, Unit 101 retaliated on the village.[13]

By various accounts of the ensuing attack, 65 to 70 Palestinian civilians, half of them women and children, were killed when Sharon's troops dynamited 45 houses and a school.[20][21][22]

Facing international condemnation for the attack, Ben-Gurion denied that the Israeli military was involved.[13] In his memoir, Sharon wrote that the unit had checked all the houses before detonating the explosives and that he thought the houses were empty.[21] Although he admitted the results were tragic, Sharon defended the attack, however: "Now people could feel that the terrorist gangs would think twice before striking, now that they knew for sure they would be hit back. Kibbya also put the Jordanian and Egyptian governments on notice that if Israel was vulnerable, so were they."[20]

A few months after its founding, Unit 101 was merged with the 890 Paratroopers Battalion to create the Paratroopers Brigade, of which Sharon would also later become commander. Like Unit 101, it continued raids into Arab territory, culminating with the attack on the Qalqilyah police station in the autumn of 1956.[23][24]

Leading up to the Suez War, the missions Sharon took part in included:[citation needed]

- Operation Shoshana (now known as the Qibya massacre)

- Operation Black Arrow

- Operation Elkayam

- Operation Egged

- Operation Olive Leaves

- Operation Volcano

- Operation Gulliver (מבצע גוליבר)

- Operation Lulav (מבצע לולב)

During a payback operation in the Deir al-Balah refugee camp in the Gaza Strip, Sharon was again wounded by gunfire, this time in the leg.[13] Incidents such as those involving Meir Har-Zion, along with many others, contributed to the tension between Prime Minister Moshe Sharett, who often opposed Sharon's raids, and Moshe Dayan, who had become increasingly ambivalent in his feelings towards Sharon. Later in the year, Sharon was investigated and tried by the Military Police for disciplining one of his subordinates. However, the charges were dismissed before the onset of the Suez War.[citation needed]

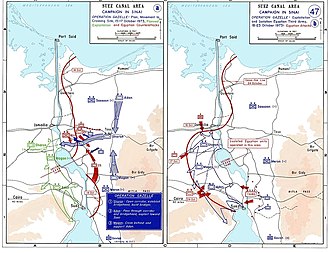

1956 Suez War

Sharon commanded Unit 202 (the Paratroopers Brigade) during the 1956 Suez War (the British "Operation Musketeer"), leading the troop to take the ground east of the Sinai's Mitla Pass and eventually the pass itself against the advice of superiors, suffering heavy Israeli casualties in the process.[25] Having successfully carried out the first part of his mission (joining a battalion parachuted near Mitla with the rest of the brigade moving on ground), Sharon's unit was deployed near the pass. Neither reconnaissance aircraft nor scouts reported enemy forces inside the Mitla Pass. Sharon, whose forces were initially heading east, away from the pass, reported to his superiors that he was increasingly concerned with the possibility of an enemy thrust through the pass, which could attack his brigade from the flank or the rear.

Sharon asked for permission to attack the pass several times, but his requests were denied, though he was allowed to check its status so that if the pass was empty, he could receive permission to take it later. Sharon sent a small scout force, which was met with heavy fire and became bogged down due to vehicle malfunction in the middle of the pass. Sharon ordered the rest of his troops to attack in order to aid their comrades. Sharon was criticized by his superiors and was damaged by allegations several years later made by several former subordinates, who claimed that Sharon tried to provoke the Egyptians and sent out the scouts in bad faith, ensuring that a battle would ensue.

Sharon had assaulted Themed in a dawn attack, and had stormed the town with his armor through the Themed Gap.[26] Sharon routed the Sudanese police company, and captured the settlement. On his way to the Nakla, Sharon's men came under attack from Egyptian MIG-15s. On the 30th, Sharon linked up with Eytan near Nakla.[27] Dayan had no more plans for further advances beyond the passes, but Sharon nonetheless decided to attack the Egyptian positions at Jebel Heitan.[27] Sharon sent his lightly armed paratroopers against dug-in Egyptians supported by aircraft, tanks and heavy artillery. Sharon's actions were in response to reports of the arrival of the 1st and 2nd Brigades of the 4th Egyptian Armored Division in the area, which Sharon believed would annihilate his forces if he did not seize the high ground. Sharon sent two infantry companies, a mortar battery and some AMX-13 tanks under the command of Mordechai Gur into the Heitan Defile on the afternoon of October 31, 1956. The Egyptian forces occupied strong defensive positions and brought down heavy anti-tank, mortar and machine gun fire on the IDF force.[28] Gur's men were forced to retreat into the "Saucer", where they were surrounded and came under heavy fire. Hearing of this, Sharon sent in another task force while Gur's men used the cover of night to scale the walls of the Heitan Defile. During the ensuing action, the Egyptians were defeated and forced to retreat. A total of 260 Egyptian and 38 Israeli soldiers were killed during the battle at Mitla. Due to these deaths, Sharon's actions at Mitla were surrounded in controversy, with many within the IDF viewing the deaths as the result of unnecessary and unauthorized aggression.[27]

Six-Day War, War of Attrition and Yom Kippur War

"It was a complex plan. But the elements that went into it were ones I had been developing and teaching for many years... the idea of close combat, nightfighting, surprise paratroop assault, attack from the rear, attack on a narrow front, meticulous planning, the concept of the 'tahbouleh', the relationship between headquarters and field command... But all the ideas had matured already; there was nothing new in them. It was simply a matter of putting all the elements together and making them work."

Ariel Sharon, 1989, on his command at the Battle of Abu-Ageila[29]

The Mitla incident hindered Sharon's military career for several years. In the meantime, he occupied the position of an infantry brigade commander and received a law degree from Tel Aviv University. However, when Yitzhak Rabin became Chief of Staff in 1964, Sharon began again to rise rapidly in the ranks, occupying the positions of Infantry School Commander and Head of Army Training Branch, eventually achieving the rank of Aluf (Major General).

Assigned a defensive role in the 1967 Six-Day War, Sharon, in command of the most powerful armored division on the Sinai front, instead drew up his own complex offensive strategy that combined infantry troops, tanks and paratroopers from planes and helicopters to destroy the Egyptian forces Sharon's brigade faced when it broke through to the Kusseima-Abu-Ageila fortified area.[13]

Sharon's victories and offensive strategy in the Battle of Abu-Ageila led to international commendation by military strategists; he was judged to have inaugurated a new paradigm in operational command. Researchers at the United States Army Training and Doctrine Command studied Sharon's operational planning, concluding that it involved a number of unique innovations. It was a simultaneous attack by a multiplicity of small forces, each with a specific aim, attacking a particular unit in a synergistic Egyptian defense network. As a result, instead of supporting and covering each other as they were designed to do, each Egyptian unit was left fighting for its own life.[30]

Sharon played a key role in the War of Attrition. In 1969, he was appointed the Head of IDF's Southern Command. As leader of the southern command, on July 29 Israeli frogmen stormed and destroyed Green Island, a fortress at the northern end of the Gulf of Suez whose radar and antiaircraft installations controlled that sector's airspace. On September 9 Sharon's forces carried out a large-scale raid along the western shore of the Gulf of Suez. Landing craft ferried across Russian-made tanks and armored personnel carriers that Israel had captured in 1967, and the small column harried the Egyptians for ten hours.[31]

Following his appointment to the southern command, Sharon had no further promotions, and considered retiring. Sharon discussed the issue with Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, who strongly advised him to remain at his post.[32] Sharon remained in the military for another three years, before retiring in August 1973. Soon after, he helped found the Likud ("Unity") political party.[33]

At the start of the Yom Kippur War on October 6, 1973, Sharon was called back to active duty along with his assigned reserve armored division. On his farm, before he left for the front line, the Reserve Commander, Zeev Amit, said to him, "How are we going to get out of this?" Sharon replied, "You don't know? We will cross the Suez Canal and the war will end over there." Sharon arrived at the front, to participate in his fourth war, in a civilian car.[34] His forces did not engage the Egyptian Army immediately, despite his requests. Under cover of darkness, Sharon's forces moved to a point on the Suez Canal that had been prepared before the war. In a move that again thwarted the commands of his superiors, Sharon's division crossed the Suez, effectively winning the war for Israel.[13] He then headed north towards Ismailia, intent on cutting the Egyptian second army's supply lines, but his division was halted south of the Fresh Water Canal.[35]

Abraham Adan's division passed over the bridgehead into Africa, advancing to within 101 kilometers of Cairo. His division managed to encircle Suez, cutting off and encircling the Third Army. Tensions between the two generals followed Sharon's decision, but a military tribunal later found his action was militarily effective.

Sharon's complex ground maneuver is regarded as a decisive move in the Yom Kippur War, undermining the Egyptian Second Army and encircling the Egyptian Third Army.[36] This move was regarded by many Israelis as the turning point of the war in the Sinai front. Thus, Sharon is widely viewed as the hero of the Yom Kippur War, responsible for Israel's ground victory in the Sinai in 1973.[13] A photo of Sharon wearing a head bandage on the Suez Canal became a famous symbol of Israeli military prowess.

Sharon's political positions were controversial, and he was relieved of duty in February 1974.

Early political career

Beginnings of political career

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2014) |

In the 1940s and 1950s, Sharon seemed to be personally devoted to the ideals of Mapai, the predecessor of the modern Labor Party. However, after retiring from military service, he was instrumental in establishing Likud in July 1973 by a merger of Herut, the Liberal Party and independent elements.[13] Sharon became chairman of the campaign staff for that year's elections, which were scheduled for November. Two and a half weeks after the start of the election campaign, the Yom Kippur War erupted and Sharon was called back to reserve service. On the heels of being hailed as a war hero for crossing the Suez in the 1973 war, Sharon won a seat to the Knesset in the elections that year,[13] but resigned a year later.

From June 1975 to March 1976, Sharon was a special aide to Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin. He planned his return to politics for the 1977 elections; first, he tried to return to the Likud and replace Menachem Begin at the head of the party. He suggested to Simha Erlich, who headed the Liberal Party bloc in the Likud, that he was more fitting than Begin to win an election victory; he was rejected, however. He then tried to join the Labor Party and the centrist Democratic Movement for Change, but was rejected by those parties too. Only then did he form his own list, Shlomtzion, which won two Knesset seats in the subsequent elections. Immediately after the elections, he merged Shlomtzion with the Likud and became Minister of Agriculture.

When Sharon joined Begin's government, he had relatively little political experience. During this period, Sharon supported the Gush Emunim settlements movement and was viewed as the patron of the settlers' movement. He used his position to encourage the establishment of a network of Israeli settlements in the occupied territories to prevent the possibility of Palestinian Arabs' return to these territories. Sharon doubled the number of Jewish settlements on the West Bank and Gaza Strip during his tenure.

On his settlement policy, Sharon said while addressing a meeting of the Tzomet party: "Everybody has to move, run and grab as many (Judean) hilltops as they can to enlarge the (Jewish) settlements because everything we take now will stay ours. ... Everything we don't grab will go to them."[37]

After the 1981 elections, Begin rewarded Sharon for his important contribution to Likud's narrow win, by appointing him Minister of Defense.

1982 Lebanon War and Sabra and Shatila massacre

As Defense Minister, Sharon launched an invasion of Lebanon called Operation Peace for Galilee, later known as the 1982 Lebanon War, following the shooting of Israel's ambassador in London, Shlomo Argov. Sharon intended the operation to eradicate the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) from its state within a state inside Lebanon, but the war is primarily remembered for the Sabra and Shatila massacre.[38] In a three-day massacre between September 16 and 18, between 762 and 3,500 civilians, mostly Palestinians and Lebanese Shiites, in the Sabra neighborhood and the adjacent Shatila refugee camp were killed by the Phalanges— Lebanese Maronite Christian militias.[39] Nearly all of those killed were women, children or elderly men.[40]

The Phalange militia went into the camps to clear out PLO fighters while Israeli forces surrounded the camps,[40] blocking camp exits and providing logistical support. The killings led some to label Sharon "the Butcher of Beirut".[41]

An Associated Press report on September 15, 1982 stated, "Defence Minister Ariel Sharon, in a statement, tied the killing [of the Phalangist leader Bachir Gemayel] to the PLO, saying 'it symbolises the terrorist murderousness of the PLO terrorist organisations and their supporters'."[42] Habib Chartouni, a Lebanese Christian from the Syrian Socialist National Party confessed to the murder of Gemayel, and no Palestinians were involved.

Robert Maroun Hatem, Hobeika's bodyguard, stated in his book From Israel to Damascus that Hobeika ordered the massacre of civilians in defiance of Israeli instructions to behave like a "dignified" army.[43]

The massacre followed intense Israeli bombings of Beirut that had seen heavy civilian casualties, testing Israel's relationship with the United States in the process.[40] America sent troops to help negotiate the PLO's exit from Lebanon, withdrawing them after negotiating a ceasefire that ostensibly protected Palestinian civilians.[40]

Legal findings

After 400,000 Peace Now protesters rallied in Tel Aviv to demand an official government inquiry into the massacres, the official Israeli government investigation into the massacre at Sabra and Shatila, the Kahan Commission (1982), was conducted.[13] The inquiry found that the Israeli Defense Forces were indirectly responsible for the massacre since IDF troops held the area.[40] The commission determined that the killings carried out by a Phalangist unit acting on its own, but its entry was known to Israel and approved by Sharon. Prime Minister Begin was also found responsible for not exercising greater involvement and awareness in the matter of introducing the Phalangists into the camps.

The commission also concluded that Sharon bore personal responsibility[40] "for ignoring the danger of bloodshed and revenge [and] not taking appropriate measures to prevent bloodshed". It said Sharon's negligence in protecting the civilian population of Beirut, which had come under Israeli control, amounted to a dereliction of duty of the minister.[3] In early 1983, the commission recommended the removal of Sharon from his post as defense minister and stated:

We have found ... that the Minister of Defense [Ariel Sharon] bears personal responsibility. In our opinion, it is fitting that the Minister of Defense draw the appropriate personal conclusions arising out of the defects revealed with regard to the manner in which he discharged the duties of his office— and if necessary, that the Prime Minister consider whether he should exercise his authority ... to ... remove [him] from office."[44]

Sharon initially refused to resign as defense minister, and Begin refused to fire him. After a grenade was thrown into a dispersing crowd at an Israeli Peace Now march, killing Emil Grunzweig and injuring 10 others, a compromise was reached: Sharon agreed to forfeit the post of defense minister but stayed in the cabinet as a minister without portfolio.

Sharon's resignation as defense minister is listed as one of the important events of the Tenth Knesset.[45]

In its February 21, 1983 issue, Time published an article implying that Sharon was directly responsible for the massacres.[46] Sharon sued Time for libel in American and Israeli courts. Although the jury concluded that the Time article included false allegations, they found that Time had not acted with "actual malice" and so was not guilty of libel.[47]

On June 18, 2001, relatives of the victims of the Sabra massacre began proceedings in Belgium to have Sharon indicted on alleged war crimes charges.[48] Elie Hobeika, the leader of the Phalange militia who carried out the massacres, was assassinated in January 2001, several months before he was scheduled to testify trial.[49] In June 2002, a Brussels Appeals Court rejected the lawsuit because the law was subsequently changed to disallow such lawsuits unless a Belgian citizen is involved.[50]

Political downturn and recovery

"I begin with the basic conviction that Jews and Arabs can live together. I have repeated that at every opportunity, not for journalists and not for popular consumption, but because I have never believed differently or thought differently, from my childhood on. ... I know that we are both inhabitants of the land, and although the state is Jewish, that does not mean that Arabs should not be full citizens in every sense of the word."

Ariel Sharon, 1989[51]

After his dismissal from the Defense Ministry post, Sharon remained in successive governments as a minister without portfolio (1983–1984), Minister for Trade and Industry (1984–1990), and Minister of Housing Construction (1990–1992). In the Knesset, he was member of the Foreign Affairs and Defense committee (1990–1992) and Chairman of the committee overseeing Jewish immigration from the Soviet Union. During this period he was a rival to then prime minister Yitzhak Shamir, but failed in various bids to replace him as chairman of Likud. Their rivalry reached a head in February 1990, when Sharon grabbed the microphone from Shamir, who was addressing the Likud central committee, and famously exclaimed: "Who's for wiping out terrorism?"[52] The incident was widely viewed as an apparent coup attempt against Shamir's leadership of the party.

In Benjamin Netanyahu's 1996–1999 government, Sharon was Minister of National Infrastructure (1996–98), and Foreign Minister (1998–99). Upon the election of the Barak Labor government, Sharon became leader of the Likud party.

Campaign for Prime Minister, 2000–2001

On September 28, 2000, Sharon and an escort of over 1,000 Israeli police officers visited the Temple Mount complex, site of the Dome of the Rock and al-Aqsa Mosque, the holiest place in the world to Jews and the third holiest site in Islam. Sharon declared that the complex would remain under perpetual Israeli control. Palestinian commentators accused Sharon of purposely inflaming emotions with the event to provoke a violent response and obstruct success of delicate ongoing peace talks. On the following day, a large number of Palestinian demonstrators and an Israeli police contingent confronted each other at the site. According to the U.S. State Department, "Palestinians held large demonstrations and threw stones at police in the vicinity of the Western Wall. Police used rubber-coated metal bullets and live ammunition to disperse the demonstrators, killing 4 persons and injuring about 200." According to the government of Israel, 14 policemen were injured.[citation needed]

Sharon's visit, a few months before his election as Prime Minister, came after archeologists claimed that extensive building operations at the site were destroying priceless antiquities. Sharon's supporters claim that Yasser Arafat and the Palestinian National Authority planned the Second Intifada months prior to Sharon's visit.[53][54][55] They state that Palestinian security chief Jabril Rajoub provided assurances that if Sharon did not enter the mosques, no problems would arise. They also often quote statements by Palestinian Authority officials, particularly Imad Falouji, the P.A. Communications Minister, who admitted months after Sharon's visit that the violence had been planned in July, far in advance of Sharon's visit, stating the intifada "was carefully planned since the return of (Palestinian President) Yasser Arafat from Camp David negotiations rejecting the U.S. conditions".[56] According to the Mitchell Report,

the government of Israel asserted that the immediate catalyst for the violence was the breakdown of the Camp David negotiations on 25 July 2000 and the "widespread appreciation in the international community of Palestinian responsibility for the impasse." In this view, Palestinian violence was planned by the PA leadership, and was aimed at "provoking and incurring Palestinian casualties as a means of regaining the diplomatic initiative."

The Mitchell Report found that

the Sharon visit did not cause the Al-Aqsa Intifada. But it was poorly timed and the provocative effect should have been foreseen; indeed, it was foreseen by those who urged that the visit be prohibited. More significant were the events that followed: The decision of the Israeli police on 29 September to use lethal means against the Palestinian demonstrators.

In addition, the report stated,

Accordingly, we have no basis on which to conclude that there was a deliberate plan by the PA to initiate a campaign of violence at the first opportunity; or to conclude that there was a deliberate plan by the GOI to respond with lethal force.[57]

The Or Commission, an Israeli panel of inquiry appointed to investigate the October 2000 events,

criticised the Israeli police for being unprepared for the riots and possibly using excessive force to disperse the mobs, resulting in the deaths of 12 Arab Israeli, one Jewish and one Palestinian citizens.

A survey conducted by Tel Aviv University's Jaffe Center in May 2004 found that 80% of Jewish Israelis believed that the Israel Defense Forces had succeeded in militarily countering the Al-Aqsa Intifada.[58]

Prime minister

After the collapse of Barak's government, Sharon was elected Prime Minister in February 2001, defeating Barak 68 percent to 32 percent.[13] Sharon's senior adviser was Raanan Gissin. In his first act as prime minister, Sharon invited the Labor Party to join in a coalition with Likud.[13]

In September 2003, Sharon became the first prime minister of Israel to visit India, saying that Israel regarded India as one of the most important countries in the world. Some analysts speculated on the development of a three-way military axis of New Delhi, Washington, D.C. and Jerusalem.[59]

On July 20, 2004, Sharon called on French Jews to emigrate from France to Israel immediately, in light of an increase in French antisemitism (94 antisemitic assaults were reported in the first six months of 2004, compared to 47 in 2003). France has the third-largest Jewish population in the world (about 600,000 people). Sharon observed that an "unfettered anti-Semitism" reigned in France. The French government responded by describing his comments as "unacceptable", as did the French representative Jewish organization CRIF, which denied Sharon's claim of intense anti-Semitism in French society. An Israeli spokesperson later claimed that Sharon had been misunderstood. France then postponed a visit by Sharon. Upon his visit, both Sharon and French President Jacques Chirac were described as showing a willingness to put the issue behind them.[citation needed]

Unilateral disengagement

In September 2001, Sharon stated for the first time that Palestinians should have the right to establish their own land west of the Jordan River.[13] In May 2003, Sharon endorsed the Road Map for Peace put forth by the United States, European Union, and Russia, which opened a dialogue with Mahmud Abbas, and announced his commitment to the creation of a Palestinian state in the future.

He embarked on a course of unilateral withdrawal from the Gaza Strip, while maintaining control of its coastline and airspace. Sharon's plan was welcomed by both the Palestinian Authority and Israel's left wing as a step towards a final peace settlement. However, it was greeted with opposition from within his own Likud party and from other right wing Israelis, on national security, military, and religious grounds.

Disengagement from Gaza

On December 1, 2004, Sharon dismissed five ministers from the Shinui party for voting against the government's 2005 budget. In January 2005, Sharon formed a national unity government that included representatives of Likud, Labor, and Meimad and Degel HaTorah as "out-of-government" supporters without any seats in the government (United Torah Judaism parties usually reject having ministerial offices as a policy). Between August 16 and 30, 2005, Sharon controversially expelled 9,480 Jewish settlers from 21 settlements in Gaza and four settlements in the northern West Bank. Once it became clear that the evictions were definitely going ahead, a group of conservative Rabbis, led by Yosef Dayan, placed an ancient curse on Sharon known as the Pulsa diNura, calling on the Angel of Death to intervene and kill him. After Israeli soldiers bulldozed every settlement structure except for several former synagogues, Israeli soldiers formally left Gaza on September 11, 2005 and closed the border fence at Kissufim. While his decision to withdraw from Gaza sparked bitter protests from members of the Likud party and the settler movement, opinion polls showed that it was a popular move among most of the Israeli electorate, with more than 80 percent of Israelis backing the plans.[60] On September 27, 2005, Sharon narrowly defeated a leadership challenge by a 52–48 percent vote. The move was initiated within the central committee of the governing Likud party by Sharon's main rival, Benjamin Netanyahu, who had left the cabinet to protest Sharon's withdrawal from Gaza. The measure was an attempt by Netanyahu to call an early primary in November 2005 to choose the party's leader.

Founding of Kadima

On November 21, 2005, Sharon resigned as head of Likud, and dissolved parliament to form a new centrist party called Kadima ("Forward"). November polls indicated that Sharon was likely to be returned to the prime ministership. On December 20, 2005, Sharon's longtime rival Netanyahu was elected his successor as leader of Likud.[61] Following Sharon's incapacitation, Ehud Olmert replaced Sharon as Kadima's leader, for the nearing general elections. Likud, along with the Labor Party, were Kadima's chief rivals in the March 2006 elections.

Sharon's stroke occurred a few months before he had been expected to win a new election and was widely interpreted as planning on "clearing Israel out of most of the West Bank", in a series of unilateral withdrawals.[4][5][6]

In the elections, which saw Israel's lowest-ever voter turnout of 64 percent[62] (the number usually averages on the high 70%), Kadima, headed by Olmert, received the most Knesset seats, followed by Labor. The new governing coalition installed in May 2006 included Kadima, with Olmert as Prime Minister, Labor (including Peretz as Defense Minister), the Gil (Pensioner's) Party, the Shas religious party, and Israel Beytenu.

Alleged fundraising irregularities and Greek island affair

During the latter part of his career, Sharon was investigated for alleged involvement in a number of financial scandals, in particular, the Greek Island Affair and irregularities of fundraising during the 1999 election campaign. In the Greek Island Affair, Sharon was accused of promising (during his term as Foreign Minister) to help Israeli businessman David Appel in his development project on a Greek island in exchange for large consultancy payments to Sharon's son Gilad. The charges were later dropped due to lack of evidence. In the 1999 election fundraising scandal, Sharon was not charged with any wrongdoing, but his son Omri, a Knesset member at the time, was charged and sentenced in 2006 to nine months in prison.

To avoid a potential conflict of interest in relation to these investigations, Sharon was not involved in the confirmation of the appointment of a new attorney general, Menahem Mazuz, in 2005.

On December 10, 2005, Israeli police raided Martin Schlaff's apartment in Jerusalem. Another suspect in the case was Robert Nowikovsky, an Austrian involved in Russian state-owned company Gazprom's business activities in Europe.[63][64][65][66]

According to Haaretz, "The $3 million that parachuted into Gilad and Omri Sharon's bank account toward the end of 2002 was transferred there in the context of a consultancy contract for development of kolkhozes (collective farms) in Russia. Gilad Sharon was brought into the campaign to make the wilderness bloom in Russia by Getex, a large Russian-based exporter of seeds (peas, millet, wheat) from Eastern Europe. Getex also has ties with Israeli firms involved in exporting wheat from Ukraine, for example. The company owns farms in Eastern Europe and is considered large and prominent in its field. It has its Vienna offices in the same building as Jurimex, which was behind the $1-million guarantee to the Yisrael Beiteinu party."[67]

On December 17, police announced that they had found evidence of a $3 million bribe paid to Sharon's sons. Shortly after the announcement, Sharon suffered a stroke.[63]

Illness, incapacitation and death

| "I love life. I love all of it, and in fact I love food." |

| —Ariel Sharon, 1982[2] |

Sharon suffered from obesity from the 1980s and also had suspected chronic high blood pressure and high cholesterol – at 170 cm (5 ft 7 in) tall, he was reputed to weigh 115 kg (254 lb).[68] Stories of Sharon's appetite and obesity were legendary in Israel. He would often joke about his love of food and expansive girth.[69] His staff car would reportedly be stocked with snacks, vodka, and caviar.[2] In October 2004 when asked why he did not wear a bulletproof vest despite frequent death threats, Sharon smiled and replied, "There is none that fits my size".[70] He was a daily consumer of cigars and luxury foods. Numerous attempts by doctors, friends, and staff to impose a balanced diet on Sharon were unsuccessful.[71]

Sharon was hospitalized on December 18, 2005, after suffering a minor ischemic stroke. During his hospital stay, doctors discovered a heart defect requiring surgery and ordered bed rest pending a cardiac catheterization scheduled for January 5, 2006. Instead, Sharon returned immediately to work and suffered a hemorrhagic stroke on January 4, the day before surgery. After two surgeries lasting 7 and 14 hours, doctors stopped the bleeding in Sharon's brain, but were unable to prevent him from entering into a coma.[72] Subsequent media reports indicated that Sharon had been diagnosed with cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) during his December hospitalisation. Hadassah Hospital Director Shlomo Mor-Yosef declined to respond to comments that the combination of CAA and blood thinners after Sharon's December stroke may have caused his more serious subsequent stroke.[73]

Ehud Olmert became Acting Prime Minister the night of Sharon's second stroke, while Sharon was only officially in office. Knesset elections followed in March, with Olmert and Sharon's Kadima party winning a plurality. The next month, the Israeli Cabinet declared Sharon permanently incapacitated and Olmert officially became Interim Prime Minister in office on April 14, 2006 until his new established government made him Prime Minister in his own right on 4 May.

Sharon underwent a series of subsequent surgeries related to his state. He remained in a long-term care facility from November 6, 2006 until the time of his death.[74] Medical experts indicated that his cognitive abilities had likely been destroyed by the stroke.[75][76][77] His condition worsened from late 2013, and Sharon suffered from renal failure on January 1, 2014.[78][79]

After spending eight years in a coma, Sharon died at 14:00 local time (12:00 UTC) on January 11, 2014.[80][81] Sharon's state funeral was held on January 13 in accordance with Jewish burial customs, which require that interment takes place as soon after death as possible. His body lay in state in the Knesset Plaza from January 12 until the official ceremony, followed by a funeral held at the family's ranch in the Negev desert. Sharon was buried beside his wife, Lily.[82][83][84] His death elicited reaction from Israeli and Palestinian leaders, among others.

Personal life

Sharon was widowed twice. Shortly after becoming a military instructor, he married Margalit Zimmermann, with whom he had a son, Gur. But Margalit died in a car accident in May 1962 and Gur died in October 1967 after a friend accidentally shot him while they were playing with a rifle.[85][86][87] After Margalit's death, Sharon married her younger sister, Lily Zimmermann. They had two sons, Omri and Gilad, and six grandchildren.[88] Lily Sharon died of lung cancer in 2000.[89]

Recognition

In 2005, he was voted the 8th-greatest Israeli of all time, in a poll by the Israeli news website Ynet to determine whom the general public considered the 200 Greatest Israelis.[90]

A $250 million park named for him is under construction outside Tel Aviv. When complete, the Ariel Sharon Park will be three times the size of New York's Central Park and introduce many new ecological technologies. A 50,000-seat amphitheatre is also planned as a national concert venue.[91][92]

References

- ^ Lis, Jonathan (January 11, 2014). "Ariel Sharon, former Israeli prime minister, dies at 85 – National Israel News". Haaretz. Retrieved January 11, 2014.

- ^ a b c "Israel's Man of War", Michael Kramer, New York, pages 19–24, August 9, 1982

- ^ a b Schiff, Ze'ev (1984). Israel's Lebanon War. Simon and Schuster. pp. 283–284. ISBN 0-671-47991-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Rees, Matt (October 22, 2011). "Ariel Sharon's fascinating appetite". Salon. Archived from the original on October 23, 2011.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; November 18, 2012 suggested (help) - ^ a b Elhanan Miller (February 19, 2013). "Sharon was about to leave two-thirds of the West Bank". The Times of Israel. Archived from the original on February 21, 2013.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|newspaper=(help) - ^ a b Derek S. Reveron, Jeffrey Stevenson Murer (2013). Flashpoints in the War on Terrorism. Routledge. p. 9.

- ^ "Scientists say comatose former Israeli leader Ariel Sharon shows 'robust' brain activity". Fox News Channel. January 28, 2013. Archived from the original on January 29, 2013. Retrieved January 12, 2014.

- ^ Soffer, Ari (January 11, 2014). "Ariel Sharon Passes Away, Aged 85". Arutz Sheva. Retrieved January 11, 2014.

- ^ Yolande Knell (January 11, 2014). "Israel's ex-PM Ariel Sharon dies, aged 85". BBC News Online. Retrieved January 11, 2014.

- ^ Ethan Bronner (January 11, 2014). "Ariel Sharon, Israeli Hawk Who Sought Peace on His Terms, Dies at 85". The New York Times. Retrieved January 11, 2014.

- ^ Itamar Eichner (March 11, 2014). "Subbotnik Jews to resume aliyah". Israel Jewish Scene. Archived from the original on March 12, 2014. Retrieved April 9, 2014.

- ^ Ariel Sharon, Samuel Willard Crompton and Richard Worth

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Lis, Jonathan (January 11, 2014). "Ariel Sharon, former Israeli prime minister, dies at 85". Haaretz. Retrieved January 13, 2014.

- ^ Honig, Sarah (February 15, 2001). "Another tack: Yoni & the Scheinermans". The Jerusalem Post.

- ^ Ariel Sharon, with David Chanoff; Warrior: The Autobiography of Ariel Sharon, Simon & Schuster, 2001, pp 41, 44.

- ^ Freedland, Jonathan (January 3, 2014). "Ariel Sharon's final mission might well have been peace", The Guardian. ("Even his name was given to him by Israel's founding father, David Ben-Gurion – turning the young Scheinerman into Sharon as if he were King Arthur anointing a knight".)

- ^ A History of Modern Israel, by Colin Shindler, Cambridge University Press, Mar 31, 2013, page 168

- ^ Benny Morris (1993). Israel's Border Wars, 1949–1956: Arab Infiltration, Israeli Retaliation, and the Countdown to the Suez War. Oxford University Press. pp. 251–253. ISBN 0-19-829262-7.

- ^ Morris, Benny (1997). Israel's Border Wars 1949–1956. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-829262-3.

- ^ a b Stannard, Matthew B. (January 11, 2014). "Ariel Sharon, former Israel PM, dies at 85". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on January 12, 2014. Retrieved January 13, 2014.

- ^ a b Bergman, Ronen (January 11, 2014). "Ariel Sharon, the Ruthless Warrior Who Could Have Made Peace". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on January 11, 2014. Retrieved January 13, 2014.

- ^ Silver, Eric (January 11, 2014). "Ariel Sharon dies: Obituary – Unlike his right-wing predecessors, former Israeli PM was 'a pragmatist who could make concessions without feeling that he was committing sacrilege'". The Independent. Archived from the original on January 12, 2014. Retrieved January 13, 2014.

- ^ "Israeli Special Forces History". Jewish Virtual Library. Archived from the original on April 28, 2003. Retrieved September 4, 2009.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; October 10, 2012 suggested (help) - ^ "Unit 101" (History). Specwar. Archived from the original on April 27, 2011. Retrieved September 6, 2009.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; October 7, 2012 suggested (help) - ^ "Ariel Sharon dies". Globes. January 14, 2014. Archived from the original on January 15, 2014. Retrieved January 13, 2014.

- ^ Varble, Derek (2003). The Suez Crisis 1956. London: Osprey. p. 90.

- ^ a b c Varble, Derek (2003). The Suez Crisis 1956. London: Osprey. p. 32.

- ^ Varble, Derek (2003). The Suez Crisis 1956. London: Osprey. p. 33.

- ^ Ariel Sharon, with David Chanoff (2001). Warrior: The Autobiography of Ariel Sharon. Simon & Schuster. pp. 190–191.

- ^ Hollow Land: Israel's Architecture of Occupation, by Eyal Weizman, Verso 2012, page 76

- ^ Ariel Sharon, Warrior, Siomon & Shuster 1989, page 223

- ^ "The Rebbe to Sharon: Dont Leave the IDF".

- ^ "Israel's generals: Ariel Sharon". UK: BBC Four. June 17, 2004. Archived from the original on May 25, 2006. Retrieved April 15, 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Ariel Sharon by Uri Dan

- ^ Dr. George W. Gawrych Archived 2009-03-25 at the Wayback Machine p.72

- ^ The Yom Kippur War 1973 (2): The Sinai, By Simon Dunstan, Osprey Publishing, April 20, 2003

- ^ Agence France Presse, November 15, 1998

- ^ Martin, Patrick (January 12, 2014). "Israel must confront Sharon's legacy". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved January 13, 2014.

- ^ Malone, Linda A. (1985). "The Kahan Report, Ariel Sharon and the SabraShatilla Massacres in Lebanon: Responsibility Under International Law for Massacres of Civilian Populations". Utah Law Review: 373–433. Retrieved January 1, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f Anziska, Seth (September 16, 2012). "A Preventable Massacre". Haaretz. Retrieved January 13, 2014.

- ^ Saleh, Heba (February 6, 2001). "Sharon victory: An Arab nightmare". BBC News Online. Archived from the original on April 27, 2011.

{{cite news}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; October 26, 2012 suggested (help) - ^ Robert Fisk (2005), The Great War for civilisation: the conquest of the Middle East, London: Fourth Estate

- ^ Robert Maroun Hatem, From Israel to Damascus, Chapter 7: "The Massacres at Sabra and Shatilla" online. Retrieved February 24, 2006.

- ^ "Report of the Commission of Inquiry into the events at the refugee camps in Beirut — 8 February 1983". Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs. February 8, 1983. Retrieved April 15, 2006.

- ^ "Knesset 9-11". Gov.il. Retrieved September 1, 2011.

- ^ Smith, William E. (February 21, 1983). "The Verdict Is Guilty: An Israeli commission and the Beirut massacre". Time. 121 (8). Archived from the original on November 22, 2008. Retrieved September 28, 2010.

{{cite journal}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; September 19, 2010 suggested (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Brooke W. Kroeger (January 25, 1984). "Sharon Loses Libel Suit; Time Cleared of Malice". Archived from the original on July 21, 2003.

{{cite news}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; March 2, 2005 suggested (help) - ^ "The Complaint Against Ariel Sharon for his involvement in the massacres at Sabra and Shatila". The Council for the Advancement of Arab-British Understanding. Archived from the original on April 4, 2006. Retrieved April 15, 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Trevor Mostyn (January 25, 2002). "Obituary: Elie Hobeika – Lebanese militia leader who massacred civilians". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved September 1, 2011.

- ^ "Cour de cassation de Belgique" (PDF) (in French). La faculté de Droit de Namur. February 12, 2003.

- ^ Ariel Sharon, with David Chanoff; Warrior: The Autobiography of Ariel Sharon, Simon & Schuster, 2001, page 543.

- ^ "Sharon Quits Cabinet in Likud Scrap". Philadelphia Daily News. February 13, 1990. Archived from the original on January 11, 2014. Retrieved January 11, 2014.

- ^ Khaled Abu Toameh (September 19, 2002). "How the war began".

- ^ Charles Krauthammer (May 20, 2001). "Middle East Troubles". Townhall.com.

{{cite web}}: Check|archiveurl=value (help) - ^ Mitchell G. Bard. "Myths & Facts Online: The Palestinian Uprisings". Jewish Virtual Library. Archived from the original on August 23, 2001. Retrieved January 14, 2014.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; February 27, 2005 suggested (help) - ^ Stewart Ain (December 20, 2000). "PA: Intifada Was Planned". The Jewish Week. Archived from the original on March 10, 2005.

- ^ "The Mitchell Report". Jewish Virtual Library. May 4, 2001. Archived from the original on July 16, 2002.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; June 25, 2009 suggested (help) - ^ "מדד השלום" (PDF) (in Hebrew). The Tami Steinmetz Center for Peace Research. May 2004.

- ^ "India and Israel vow to fight terrorism". BBC News. September 9, 2003.

- ^ "Sharon party agrees coalition plan — 9 December 2004". CNN. December 10, 2004. Archived from the original on June 25, 2009. Retrieved August 6, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Urquhart, Conal (December 20, 2005). "Sharon recovers as chief rival wins control of Likud". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on August 29, 2013. Retrieved April 25, 2010.

- ^ "Elections for the Local Authority — Who, What, When, Where and How? — The Israel Democracy Institute". Idi.org.il. Archived from the original on July 27, 2011. Retrieved August 6, 2009.

- ^ a b "Austrian tycoon may face Israel charges: report". Agence France-Presse. September 7, 2010. Archived from the original on September 10, 2010.

- ^ Hillel Fendel (January 3, 2006). "Police Say There's Evidence Linking Sharon to $3 Million Bribe". Arutz Sheva. Archived from the original on July 12, 2007.

{{cite news}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; July 19, 2010 suggested (help) - ^ "A tale of gazoviki, money and greed". Stern. September 13, 2007. Archived from the original on August 16, 2011.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Police have evidence Sharon's family takes bribes: TV". Xinhua. January 4, 2006. Archived from the original on Decemebr 19, 2006.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|archivedate=(help) - ^ "The Schlaff Saga / Money flows into the Sharon family accounts". Haaretz. December 22, 2010. Archived from the original on December 19, 2010.

{{cite news}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; November 5, 2010 suggested (help) - ^ Jim Hollander (December 26, 2005). "Ariel Sharon to undergo heart procedure". USA Today. Retrieved April 16, 2012.

{{cite news}}:|archive-url=is malformed: timestamp (help) - ^ Ravi Nessman (December 22, 2005). "Sharon's diet becoming a weighty matter". Jerusalem. Associated Press. Archived from the original on December 24, 2005.

{{cite news}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; December 9, 2009 suggested (help) - ^ "Top 10 Comas – The Big Sleep: Ariel Sharon". Time. Archived from the original on September 13, 2013.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Freddy Eytan and Robert Davies (2006). Ariel Sharon: A Life in Times of Turmoil. p. 146.

- ^ "Sharon's stroke blood 'drained'". BBC News. January 5, 2006. Archived from the original on February 11, 2006.

{{cite news}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; August 10, 2011 suggested (help) - ^ Mark Willacy (January 10, 2006). Israeli PM Sharon moves left side. ABC News. Archived from the original on October 13, 2007.

{{cite book}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; February 15, 2011 suggested (help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Sharon leaves intensive care unit". BBC News. November 6, 2006. Archived from the original on January 16, 2007.

{{cite news}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; March 14, 2009 suggested (help) - ^ "Ariel Sharon's sons to disconnect their father from life-support system". Pravda.Ru. Archived from the original on April 13, 2006. Retrieved August 6, 2009.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; June 5, 2011 suggested (help) - ^ "Sharon will never recover: doctors". The Age. Melbourne. January 6, 2010.

- ^ "Ariel Sharon transferred to long-term treatment in Tel HaShomer". Haaretz. May 28, 2006. Archived from the original on November 21, 2010. Retrieved May 28, 2006.

- ^ "Ariel Sharon's Condition Deteriorates". The Times of Israel. Archived from the original on January 2, 2014. Retrieved January 1, 2014.

- ^ "Doctors: End for Sharon Could Come 'Within Hours'". Arutz Sheva. January 2, 2014. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- ^ "Israel mourns Sharon's passing; Netanyahu: He was a 'brave warrior'". Haaretz. January 11, 2014. Retrieved January 11, 2014.

- ^ Dan Williams (January 11, 2014). "Former Israeli prime minister Ariel Sharon dead at 85". Reuters. Retrieved January 11, 2014.

- ^ "Obama: U.S. joins Israeli people in honoring Sharon's commitment to his country". Haaretz. January 11, 2014. Retrieved January 11, 2014.

- ^ Gil Hoffman, and Tovah Lazaroff (January 11, 2014). "Former prime minister Ariel Sharon dies at 85". The Jerusalem Post. Archived from the original on January 11, 2014. Retrieved January 11, 2014.

- ^ "Israel's Ariel Sharon dies at 85". Al Jazeera. January 11, 2014. Retrieved January 11, 2014.

- ^ "Sharon mourns slain son". The Sydney Morning Herald. February 15, 2005. Archived from the original on April 17, 2005. Retrieved April 15, 2006.

{{cite news}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; May 6, 2011 suggested (help) - ^ Brockes, Emma (November 7, 2001). "The Bulldozer". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on April 17, 2005. Retrieved April 15, 2006.

{{cite news}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; August 25, 2013 suggested (help) - ^ "The Quest for Peace" (transcript). CNN. June 14, 2003. Archived from the original on February 16, 2006. Retrieved March 28, 2006.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Glenn Frankel (January 11, 2014). "Ariel Sharon dies at 85: Former Israeli prime minister epitomized country's warrior past". The Washington Post.

- ^ Ben-David, Calev; Gwen (January 12, 2014). "Ariel Sharon, Israeli Warrior Who Vacated Gaza, Dies at 85". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on January 12, 2014. Retrieved January 12, 2014.

- ^ גיא בניוביץ' (June 20, 1995). "הישראלי מספר 1: יצחק רבין". Ynet (in Hebrew). Archived from the original on May 13, 2005. Retrieved July 10, 2011.

{{cite news}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; February 7, 2011 suggested (help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Sharon Udasin (May 16, 2011). "Ariel Sharon Park transforms 'eyesore' into 'paradise'". Jerusalem Post. Archived from the original on March 20, 2013.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|newspaper=(help) - ^ "Former wasteland, future ecological wonderland Ariel Sharon Park to be bigger than NYC's Central Park". Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs. July 20, 2011. Archived from the original on March 9, 2014.

Further reading

- Ben Shaul, Moshe (editor); Generals of Israel, Tel-Aviv: Hadar Publishing House, Ltd., 1968.

- Uri Dan; Ariel Sharon: An Intimate Portrait, Palgrave Macmillan, October 2006, 320 pages. ISBN 1-4039-7790-9.

- Ariel Sharon, with David Chanoff; Warrior: The Autobiography of Ariel Sharon, Simon & Schuster, 2001, ISBN 0-671-60555-0.

- Gilad Sharon, (translated by Mitch Ginsburg); Sharon: The Life of a Leader, HarperCollins Publishers, 2011, ISBN 978-0-06-172150-2.

- Nir Hefez, Gadi Bloom, (translated by Mitch Ginsburg); Ariel Sharon: A Life, Random House, October 2006, 512 pages, ISBN 1-4000-6587-9.

- Freddy Eytan, (translated by Robert Davies); Ariel Sharon: A Life in Times of Turmoil, translation of Sharon: le bras de fer, Studio 8 Books and Music, 2006, ISBN 1-55207-092-1.

- Abraham Rabinovich; The Yom Kippur War: The Epic Encounter That Transformed the Middle East, 2005, ISBN 978-0-8052-1124-5.

- Ariel Sharon, official biography, Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

- Varble, Derek (2003). The Suez Crisis 1956. London: Osprey. ISBN 9781841764184.

- Tzvi T. Avisar; Sharon: Five years forward, Publisher House, March 2011, 259 pages, Official website, ISBN 978-965-91748-0-5.

External links

- Ariel Sharon on the Knesset website

- 1928 births

- 2014 deaths

- Moshavniks

- Israeli Jews

- Ashkenazi Jews

- Haganah members

- Israeli people of the Yom Kippur War

- Israeli generals

- Jewish military personnel

- Tel Aviv University alumni

- Israeli party leaders

- Prime Ministers of Israel

- Members of the Knesset

- People with severe brain damage

- Kadima politicians

- Likud politicians

- Shlomtzion (political party) politicians

- Israeli people of Belarusian-Jewish descent

- Ariel Sharon

- Stroke survivors

- Ministers of Internal Affairs of Israel

- Israeli Ministers of Health

- Ministers of Defense of Israel

- Hebrew University of Jerusalem alumni

- History of Israel

- Deaths from renal failure