Carrot

| Carrot | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| (unranked): | |

| (unranked): | |

| (unranked): | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | D. carota

|

| Trinomial name | |

| Daucus carota subsp. sativus | |

The carrot (Daucus carota subsp. sativus) is a root vegetable, usually orange in colour, though purple, red, white, and yellow varieties exist.

It has a crisp texture when fresh. The most commonly eaten part of a carrot is a taproot, although the greens are sometimes eaten as well. It is a domesticated form of the wild carrot Daucus carota, native to Europe and southwestern Asia. The domestic carrot has been selectively bred for its greatly enlarged and more palatable, less woody-textured edible taproot. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) reports that world production of carrots and turnips (these plants are combined by the FAO for reporting purposes) for calendar year 2011 was almost 35.658 million tonnes. Almost half were grown in China. Carrots are widely used in many cuisines, especially in the preparation of salads, and carrot salads are a tradition in many regional cuisines.

Etymology

The word is first recorded in English around 1530 and was borrowed from Middle French carotte,[1] itself from Late Latin carōta, from Greek καρωτόν karōton, originally from the Indo-European root *ker- (horn), due to its horn-like shape). In Old English, carrots (typically white at the time) were not clearly distinguished from parsnips, the two being collectively called moru or more (from Proto-Indo-European *mork- "edible root", cf. German Möhre).

History

The wild ancestors of the carrot are likely to have come from Persia (regions of which are now Iran and Afghanistan), which remain the centre of diversity of Daucus carota, the wild carrot. A naturally occurring subspecies of the wild carrot, Daucus carota subsp. sativus, has been selectively bred over the centuries to reduce bitterness, increase sweetness and minimise the woody core. This has produced the familiar garden vegetable.[2][3]

When they were first cultivated, carrots were grown for their aromatic leaves and seeds rather than their roots. Carrot seeds have been found in Switzerland and Southern Germany dating to 2000–3000 BC.[4] Some close relatives of the carrot are still grown for their leaves and seeds, for example parsley, fennel, dill and cumin. The first mention of the root in classical sources is during the 1st century.[5] The plant appears to have been introduced into Europe via Spain by the Moors in the 8th century.[6] and in the 10th century, in such locations in West Asia, India and Europe, the roots were purple.[7] The modern carrot originated in Afghanistan at about this time.[5] The 12th-century Arab Andalusian agriculturist, Ibn al-'Awwam, describes both red and yellow carrots;[8] The Jewish scholar Simeon Seth also mentions roots of these colours in the 11th century.[9] Cultivated carrots appeared in China in the 14th century, and in Japan in the 18th century.[10] Orange-coloured carrots appeared in the Netherlands in the 17th century,[11] which has been related to the fact that the Dutch flag at the time, the Prince's Flag, included orange.[7] These, the modern carrots, were intended by the antiquary John Aubrey (1626–1697) when he noted in his memoranda "Carrots were first sown at Beckington in Somersetshire. Some very old Man there [in 1668] did remember their first bringing hither."[12] European settlers introduced the carrot to Colonial America in the 17th century.[13]

Purple carrots, still orange on the inside, were sold in British stores starting in 2002.[7]

Description

Daucus carota is a biennial plant that grows a rosette of leaves in the spring and summer, while building up the stout taproot that stores large amounts of sugars for the plant to flower in the second year.

Soon after germination, carrot seedlings show a distinct demarcation between the taproot and the hypocotyl. The latter is thicker and lacks lateral roots. At the upper end of the hypocotyl is the seed leaf. The first true leaf appears about 10–15 days after germination. Subsequent leaves, produced from the stem nodes, are alternating (with a single leaf attached to a node, and the leaves growing in alternate directions) and compound, and arranged in a spiral. The leaf blades are pinnate. As the plant grows, the bases of the cotyledon are pushed apart. The stem, located just above the ground, is compressed and the internodes are not distinct. When the seed stalk elongates, the tip of the stem narrows and becomes pointed, extends upward, and becomes a highly branched inflorescence. The stems grow to 60–200 cm (20–80 in) tall.[14]

Most of the taproot consists of parenchymatous outer cortex (phloem) and an inner core (xylem). High-quality carrots have a large proportion of cortex compared to core. Although a completely xylem-free carrot is not possible, some cultivars have small and deeply pigmented cores; the taproot can appear to lack a core when the colour of the cortex and core are similar in intensity. Taproots typically have a conical shape, although cylindrical and round cultivars are available. The root diameter can range from 1 cm (0.4 in) to as much as 10 cm (4 in) at the widest part. The root length ranges from 5 to 50 cm (2.0 to 19.7 in), although most are between 10 and 25 cm (4 and 10 in).[14]

Flower development begins when the flat apical meristem changes from producing leaves to an uplifted conical meristem capable of producing stem elongation and an inflorescence. The inflorescence is a compound umbel, and each umbel contains several umbellets. The first (primary) umbel occurs at the end of the main floral stem; smaller secondary umbels grow from the main branch, and these further branch into third, fourth, and even later-flowering umbels. A large primary umbel can contain up to 50 umbellets, each of which may have as many as 50 flowers; subsequent umbels have fewer flowers. Flowers are small and white, sometimes with a light green or yellow tint. They consist of five petals, five stamens, and an entire calyx. The anthers usually dehisce and the stamens fall off before the stigma becomes receptive to receive pollen. The anthers of the brown male sterile flowers degenerate and shrivel before anthesis. In the other type of male sterile flower, the stamens are replaced by petals, and these petals do not fall off. A nectar-containing disc is present on the upper surface of the carpels.[14]

Flower development is protandrous, so the anthers release their pollen before the stigma of the same flower is receptive. The arrangement is centripetal, meaning the oldest flowers are near the edge and the youngest flowers are in the center. Flowers usually first open at the periphery of the primary umbel, followed about a week later on the secondary umbels, and then in subsequent weeks in higher-order umbels. The usual flowering period of individual umbels is 7 to 10 days, so a plant can be in the process of flowering for 30–50 days. The distinctive umbels and floral nectaries attract pollinating insects. After fertilization and as seeds develop, the outer umbellets of an umbel bend inward causing the umbel shape to change from slightly convex or fairly flat to concave, and when cupped it resembles a bird's nest.[14]

The fruit that develops is a schizocarp consisting of two mericarps; each mericarp is an achene or true seed. The paired mericarps are easily separated when they are dry. Premature separation (shattering) before harvest is undesirable because it can result in seed loss. Mature seeds are flattened on the commissural side that faced the septum of the ovary. The flattened side has five longitudinal ribs. The bristly hairs that protrude from some ribs are usually removed by abrasion during milling and cleaning. Seeds also contain oil ducts and canals. Seeds vary somewhat in size, ranging from less than 500 to more than 1000 seeds per gram.[14]

The carrot is a diploid species, and has nine relatively short, uniform-length chromosomes (2n=9). The genome size is estimated to be 473 mega base pairs, which is four times larger than Arabidopsis thaliana, one-fifth the size of the maize genome, and about the same size as the rice genome.[15]

Chemistry

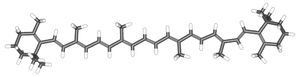

Polyacetylenes can be found in Apiaceae vegetables like carrots where they show cytotoxic activities.[16][17] Falcarinol and falcarindiol (cis-heptadeca-1,9-diene-4,6-diyne-3,8-diol)[18] are such compounds. This latter compound shows antifungal activity towards Mycocentrospora acerina and Cladosporium cladosporioides.[18] Falcarindiol is the main compound responsible for bitterness in carrots.[19]

Other compounds such as pyrrolidine (present in the leaves),[20] 6-hydroxymellein,[21] 6-methoxymellein, eugenin, 2,4,5-trimethoxybenzaldehyde (gazarin) or (Z)-3-acetoxy-heptadeca-1,9-diene-4,6-diin-8-ol (falcarindiol 3-acetate) can also be found in carrot.

Nutrition

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy | 173 kJ (41 kcal) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

9.6 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sugars | 4.7 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dietary fiber | 2.8 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

0.24 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

0.93 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other constituents | Quantity | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Fluoride | 3.2 µg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| †Percentages estimated using US recommendations for adults,[22] except for potassium, which is estimated based on expert recommendation from the National Academies.[23] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The carrot gets its characteristic, bright orange colour from β-carotene, and lesser amounts of α-carotene, γ-carotene, lutein and zeaxanthin.[24] α and β-carotenes are partly metabolized into vitamin A,[25][26] providing more than 100% of the Daily Value (DV) per 100 g serving of carrots (right table). Carrots are also a good source of vitamin K (13% DV) and vitamin B6 (11% DV), but otherwise have modest content of other essential nutrients (right table).[27]

Carrots are 88% water, 4.7% sugar, 2.6% protein, 1% ash, and 0.2% fat.[27] Carrot dietary fiber comprises mostly cellulose, with smaller proportions of hemicellulose, lignin and starch.[28] Free sugars in carrot include sucrose, glucose and fructose.[27]

The lutein and zeaxanthin carotenoids characteristic of carrots are under study for their potential roles in vision and eye health.[24][29]

Estimates have changed over time of the rate at which β-carotene is converted to vitamin A in the human body. An early estimate of 6:1 was revised to 12:1 and from recent studies and experimental trials carried out in developing nations it was revised again to 21:1. [30]

Carotenoid bioavailability ranges between 1/5 to 1/10 of retinol's. Carotenoids are better absorbed when ingested as part of a fatty meal. Also, the carotenoids in vegetables, especially those with tough cell walls (e.g. carrots), are better absorbed when these cell walls are broken up by cooking or mincing.[31]

Methods of consumption and uses

Carrots can be eaten in a variety of ways. Only 3 percent of the β-carotene in raw carrots is released during digestion: this can be improved to 39% by pulping, cooking and adding cooking oil.[32] Alternatively they may be chopped and boiled, fried or steamed, and cooked in soups and stews, as well as baby and pet foods. A well-known dish is carrots julienne.[33] Together with onion and celery, carrots are one of the primary vegetables used in a mirepoix to make various broths.[34]

The greens are edible as a leaf vegetable, but are only occasionally eaten by humans;[35] some sources suggest that the greens contain toxic alkaloids.[36][37] When used for this purpose, they are harvested young in high-density plantings, before significant root development, and typically used stir-fried, or in salads.[35] Some people are allergic to carrots. In a 2010 study on the prevalence of food allergies in Europe, 3.6 percent of young adults showed some degree of sensitivity to carrots.[38] Because the major carrot allergen, the protein Dauc c 1.0104, is cross-reactive with homologues in birch pollen (Bet v 1) and mugwort pollen (Art v 1), most carrot allergy sufferers are also allergic to pollen from these plants.[39]

In India carrots are used in a variety of ways, as salads or as vegetables added to spicy rice or dal dishes. A popular variation in north India is the Gajar Ka Halwa carrot dessert, which has carrots grated and cooked in milk until the whole mixture is solid, after which nuts and butter are added.[40] Carrot salads are usually made with grated carrots with a seasoning of mustard seeds and green chillies popped in hot oil. Carrots can also be cut in thin strips and added to rice, can form part of a dish of mixed roast vegetables or can be blended with tamarind to make chutney.[41]

Since the late 1980s, baby carrots or mini-carrots (carrots that have been peeled and cut into uniform cylinders) have been a popular ready-to-eat snack food available in many supermarkets.[42] Carrots are puréed and used as baby food, dehydrated to make chips, flakes, and powder, and thinly sliced and deep-fried, like potato chips.[28]

The sweetness of carrots allows the vegetable to be used in some fruit-like roles. Grated carrots are used in carrot cakes, as well as carrot puddings, an English dish thought to have originated in the early 19th century.[citation needed] Carrots can also be used alone or with fruits in jam and preserves. Carrot juice is also widely marketed, especially as a health drink, either stand-alone or blended with fruits and other vegetables.[43]

Companion plant

Carrots are useful companion plants for gardeners. The pungent odour of onions, leeks and chives help repel the carrot root fly,[44] and other vegetables that team well with carrots include lettuce, tomatoes and radishes, as well as the herbs rosemary and sage.[45] Carrots thrive in the presence of caraway, coriander, chamomile, marigold and Swan River daisy.[44] If left to flower, the carrot, like any umbellifer, attracts predatory wasps that kill many garden pests.[46]

Cultivation

Carrots are grown from seed and take around four months to mature. They grow best in full sun but tolerate some shade.[47] The optimum growth temperature is between 16 and 21 °C (61 and 70 °F).[48] The ideal soil is deep, loose and well-drained, sandy or loamy and with a pH of 6.3 to 6.8.[44] Fertiliser should be applied according to soil type and the crop requires low levels of nitrogen, moderate phosphate and high potash. Rich soils should be avoided, as these will cause the roots to become hairy and misshapen.[49] Irrigation should be applied when needed to keep the soil moist and the crop should be thinned as necessary and kept weed free.[50]

Cultivation problems

There are several diseases that can reduce the yield and market value of carrots. The most devastating carrot disease is Alternaria leaf blight, which has been known to eradicate entire crops. A bacterial leaf blight caused by Xanthomonas campestris can also be destructive in warm, humid areas. Root knot nematodes (Meloidogyne species) can cause stubby or forked roots, or galls.[51] Cavity spot, caused by the oomycetes Pythium violae and Pythium sulcatum, results in irregularly shaped, depressed lesions on the taproots.[52]

Physical damage can also reduce the value of carrot crops. The two main forms of damage are splitting, whereby a longitudinal crack develops during growth that can be a few centimetres to the entire length of the root, and breaking, which occurs postharvest. These disorders can affect over 30% of commercial crops. Factors associated with high levels of splitting include wide plant spacing, early sowing, lengthy growth durations, and genotype.[53]

Cultivars

Carrot cultivars can be grouped into two broad classes, eastern carrots and western carrots.[54] A number of novelty cultivars have been bred for particular characteristics.

The city of Holtville, California, promotes itself as "Carrot Capital of the World", and holds an annual festival devoted entirely to the carrot.[55]

"Eastern" (a European and American continent reference) carrots were domesticated in Persia (probably in the lands of modern-day Iran and Afghanistan within West Asia) during the 10th century, or possibly earlier. Specimens of the "eastern" carrot that survive to the present day are commonly purple or yellow, and often have branched roots. The purple colour common in these carrots comes from anthocyanin pigments.[56]

The western carrot emerged in the Netherlands in the 17th century,[57] There is a popular belief that its orange colour making it popular in those countries as an emblem of the House of Orange and the struggle for Dutch independence, although there is little evidence for this.[58] The orange colour results from abundant carotenes in these cultivars.

Western carrot cultivars are commonly classified by their root shape. The four general types are:

- Chantenay carrots. Although the roots are shorter than other cultivars, they have vigorous foliage and greater girth, being broad in the shoulders and tapering towards a blunt, rounded tip. They store well, have a pale-coloured core and are mostly used for processing.[50] Varieties include Carson Hybrid and Red Cored Chantenay.

- Danvers carrots. These have strong foliage and the roots are longer than Chantaney types, and they have a conical shape with a well-defined shoulder, tapering to a point. They are somewhat shorter than Imperator cultivars, but more tolerant of heavy soil conditions. Danvers cultivars store well and are used both fresh and for processing.[50] They were developed in 1871 in Danvers, Massachusetts.[59] Varieties include Danvers Half Long and Danvers 126.

- Imperator carrots. This cultivar has vigorous foliage, is of high sugar content, and has long and slender roots, tapering to a pointed tip. Imperator types are the most widely cultivated by commercial growers.[50] Varieties include Imperator 58 and Sugarsnax Hybrid.

- Nantes carrots. These have sparse foliage, are cylindrical, short with a more blunt tip than Imperator types, and attain high yields in a range of conditions. The skin is easily damaged and the core is deeply pigmented. They are brittle, high in sugar and store less well than other types.[50] Varieties include Nelson Hybrid, Scarlet Nantes and Sweetness Hybrid.

One particular variety lacks the usual orange pigment due to carotene, and owing its white colour to a recessive gene for tocopherol (vitamin E).[60] Derived from Daucus carota L. and patented at the University of Wisconsin–Madison,[60] the variety is intended to supplement the dietary intake of Vitamin E.[61]

-

Carrots come in a wide variety of shapes, colours and sizes.

-

Carrots with multiple taproots (forks) are not specific cultivars but are a byproduct of damage to earlier forks often associated with rocky soil.

-

Carrots can be selectively bred to produce different colours.

-

Carrot weighing and packing machine in The Netherlands.

-

Carrot seeds with a US Dime (c.18mm diameter) for size comparison.

-

Carrots of Kodaikanal

Production trends

Carrot is one of the ten most economically important vegetables crops in the world.[62] In 2012, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 36.917 million tonnes of carrots and turnips were produced worldwide for human consumption, grown on 1,196,000 hectares (2,955,000 acres) of land. With a total production of 16.907 million tonnes, China was by far the largest producer and accounted for 45.8% of the global output, followed by Russia (1.57 million tonnes), the United States (1.346), Uzbekistan (1.300), Ukraine (0.916), Poland (0.835), and the United Kingdom (0.664). About 62% of world carrot production occurred in Asia, followed by Europe (22.6%) and the Americas (North, Central, and South America and the Caribbean) (9.4%). Less than 6% of the world's 2012 total production was grown in Africa. Global production has increased from 21.4 million tonnes in 2000, 13.7 million tonnes in 1990, 10.4 million tonnes in 1980, and 7.85 million tonnes in 1970.[63] The rate of increase in the global production of carrots has been greater than the world's population growth rate, and greater than the overall increase in world vegetable production. Europe was traditionally the major centre of production, but was overtaken by Asia in 1997.[64] The growth in global production is largely the result of increases in production area rather than improvements in yield. Modest increases in the latter can be attributed to optimised agricultural practices, the development of better cultivars (including hybrids), and increased farm mechanisation.[65]

Storage

Carrots can be stored for several months in the refrigerator or over winter in a moist, cool place. For long term storage, unwashed carrots can be placed in a bucket between layers of sand, a 50/50 mix of sand and wood shavings, or in soil. A temperature range of 32 to 40 °F (0 to 5 °C) is best.[66][67]

See also

- Arracacha

- Carrot and stick

- Carrot bread

- Carrot fly

- Carrot harvester

- Carrot seed oil

- Daikon, a large East Asian white radish sometimes known as "white carrots"

- Skirret

References

- ^ "Carrot". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- ^ Rose, F. (2006). The Wild Flower Key. London: Frederick Warne. p. 346. ISBN 0-7232-5175-4.

- ^ Mabey, R. (1997). Flora Britannica. London: Chatto and Windus. p. 298. ISBN 1-85619-377-2.

- ^ Robatsky et al. (1999), p. 6.

- ^ a b Simon et al. (2008), p. 328.

- ^ Krech, Shepard; McNeill, J.R.; Merchant, Carolyn (2004). Encyclopedia of World Environmental History: O-Z, Index. Routledge. p. 1071. ISBN 978-0-415-93735-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c "Carrots return to purple roots". BBC. May 16, 2002. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- ^ Staub, Jack E. (2010). Alluring Lettuces: And Other Seductive Vegetables for Your Garden. Gibbs Smith. p. 230. ISBN 978-1-4236-0829-5.

- ^ Dalby, Andrew (2003). Food in the Ancient World from A to Z. Psychology Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-415-23259-3.

- ^ Simon et al. (2008). p. 328.

- ^ Otto Banga (1963). Main Types of the Western Carotene Carrot and their Origin. Tjeenk Willink.

- ^ Oliver Lawson Dick, ed. Aubrey's Brief Lives. Edited from the Original Manuscripts, 1949, p. xxxv.

- ^ Robatsky et al. (1999), pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b c d e Rubatsky et al. pp. 22–28.

- ^ Bradeen and Simon (2007), p. 162.

- ^ Zidorn, Christian; Jöhrer, Karin; Ganzera, Markus Schubert, Birthe; Sigmund, Elisabeth Maria ; Mader, Judith; Greil, Richard; Ellmerer, Ernst P.; Stuppner, Hermann (2005). "Polyacetylenes from the Apiaceae vegetables carrot, celery, fennel, parsley, and parsnip and their cytotoxic activities". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 53 (7): 2518–2523. doi:10.1021/jf048041s. PMID 15796588.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Baranska, Malgorzata; Schulz, Hartwig; Baranski, Rafal; Nothnagel, Thomas; Christensen, Lars P. (2005). "In situ simultaneous analysis of polyacetylenes, carotenoids and polysaccharides in carrot roots". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 53 (17): 6565–6571. doi:10.1021/jf0510440.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Garrod, B.; Lewis, B.G.; Coxon, D.T. (1978). "Cis-heptadeca-1,9-diene-4,6-diyne-3,8-diol, an antifungal polyacetylene from carrot root tissue". Physiological Plant Pathology. 13 (2): 241–246. doi:10.1016/0048-4059(78)90039-5.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Czepa, Andreas; Hofmann, Thomas (2003). "Structural and sensory characterization of compounds contributing to the bitter off-taste of carrots (Daucus carota L.) and carrot puree". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 51 (13): 3865–3873. doi:10.1021/jf034085+. PMID 12797757.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ O'Neil, M.J. (ed). (2006). The Merck Index – An Encyclopedia of Chemicals, Drugs, and Biologicals (14th ed.). Royal Society of Chemistry. ISBN 978-0-911910-00-1.

- ^ Kurosaki, Fumiya; Nishi, Arasuke (1988). "A methyltransferase for synthesis of the phytoalexin 6-methoxymellein in carrot cells". FEBS Letters. 227 (2): 183–186. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(88)80894-9.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ United States Food and Drug Administration (2024). "Daily Value on the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels". FDA. Archived from the original on 2024-03-27. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board; Committee to Review the Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium (2019). Oria, Maria; Harrison, Meghan; Stallings, Virginia A. (eds.). Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US). ISBN 978-0-309-48834-1. PMID 30844154. Archived from the original on 2024-05-09. Retrieved 2024-06-21.

- ^ a b "Dietary sources of lutein and zeaxanthin carotenoids and their role in eye health". Nutrients. 5 (4): 1169–85. 2013. doi:10.3390/nu5041169. PMC 3705341. PMID 23571649.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Strube, Michael; OveDragsted, Lars (1999). Naturally Occurring Antitumourigens. IV. Carotenoids Except β-Carotene. Copenhagen: Nordic Council of Ministers. p. 48. ISBN 978-92-893-0342-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Novotny, Janet A.; Dueker, S.R.; Zech, L.A.; Clifford, A.J. (1995). "Compartmental analysis of the dynamics of β-carotene metabolism in an adult volunteer". Journal of Lipid Research. 36 (8): 1825–1838. PMID 7595103.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c "Nutrition facts for carrots, raw [Includes USDA commodity food A099], per 100 g, USDA Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, version SR-21". Conde Nast. 2014. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ^ a b Rubatsky et al. (1999), p. 254.

- ^ Johnson EJ (2014). "Role of lutein and zeaxanthin in visual and cognitive function throughout the lifespan". Nutr Rev. 72 (9): 605–12. doi:10.1111/nure.12133. PMID 25109868.

- ^ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Retinol#Dietary intake

- ^ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Retinol#Dietary intake

- ^ Hedrén, E.; Diaz, V.; Svanburg, U. (2002). "Estimation of carotenoid accessibility from carrots determined by an in vitro digestion method". European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 56 (5): 425–430. doi:10.1038/sj/ejcn/1601329. PMID 12001013.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Martino, Robert S. (2006). Enjoyable Cooking. AuthorHouse. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-4259-6658-4.

- ^ Gisslen, Wayne (2010). Professional Cooking, College Version. John Wiley & Sons. p. 146. ISBN 978-0-470-19752-3.

- ^ a b Rubatsky et al. (1999), p. 253.

- ^ Yeager, Selene; Editors of Prevention (2008). The Doctors Book of Food Remedies: The Latest Findings on the Power of Food to Treat and Prevent Health Problems – From Aging and Diabetes to Ulcers and Yeast Infections. Rodale. p. 366. ISBN 978-1-60529-506-0.

{{cite book}}:|author2=has generic name (help) - ^ Brown, Ellen (2012). The Complete Idiot's Guide to Smoothies. DK Publishing. p. 21. ISBN 978-1-4362-9393-8.

- ^ Burney, P.; Summers, C.; Chinn, S.; Hooper, R.; Van Ree, R.; Lidholm, J. (2010). "Prevalence and distribution of sensitization to foods in the European Community Respiratory Health Survey: A EuroPrevall analysis". Allergy. 65 (9): 1182–1188. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2010.02346.x.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ballmer-Weber, B.K.; Skamstrup Hansen, K.; Sastre, J.; Andersson, K.; Bätscher, I.; Ostling, J.; Dahl, L.; Hanschmann, K.M.; Holzhauser, T.; Poulsen, L.K.; Lidholm, J.; Vieths, S. (2012). "Component-resolved in vitro diagnosis of carrot allergy in three different regions of Europe". Allergy. 67 (6): 758–766. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2012.02827.x. PMID 22486768.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gupta, Niru (2000). Cooking the Up Way. Orient Blackswan. p. 17. ISBN 978-81-250-1558-1.

- ^ Chapman, Pat (2007). India Food and Cooking: The Ultimate Book on Indian Cuisine. New Holland Publishers. pp. 158–230. ISBN 978-1-84537-619-2.

- ^ Bidlack, Wayne R.; Rodriguez, Raymond L. (2011). Nutritional Genomics: The Impact of Dietary Regulation of Gene Function on Human Disease. CRC Press. p. 321. ISBN 978-1-4398-4452-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Shannon, Nomi (1998). The Raw Gourmet. Book Publishing Company. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-920470-48-0.

- ^ a b c Cunningham, Sally Jean (2000). Great Garden Companions: A Companion-Planting System for a Beautiful, Chemical-Free Vegetable Garden. Rodale. pp. 195–196. ISBN 978-0-87596-847-6.

- ^ Riotte, L. (1998). Carrots Love Tomatoes: Secrets of Companion Planting for Successful Gardening. Storey Publishing, LLC. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-60342-396-0.

- ^ Carr, Anna (1998). Rodale's Illustrated Encyclopedia of Herbs. Rodale. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-87596-964-0.

- ^ Elzer-Peters, K. (2014). Midwest Fruit & Vegetable Gardening: Plant, Grow, and Harvest the Best Edibles – Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota & Wisconsin. Cool Springs Press. p. 136. ISBN 978-1-61058-960-4.

- ^ Benjamin et al. 1997, p. 557.

- ^ Abbott, Catherine (2012). The Year-Round Harvest: A Seasonal Guide to Growing, Eating, and Preserving the Fruits and Vegetables of Your Labor. Adams Media. pp. 54–55. ISBN 978-1-4405-2816-3.

- ^ a b c d e Production guidelines for carrot (PDF) (Report). Agriculture, Forestry & Fisheries Department: Republic of South Africa.

- ^ Davis, R. Michael (2004). "Carrot diseases and their management". In Naqvi S.A.M.H. (ed.). Diseases of Fruits and Vegetables: Diagnosis and Management. Springer. pp. 397–439. ISBN 978-1-4020-1822-0.

- ^ "Carrot cavity spot". University of California Agriculture & Natural Resources. September 2012. Retrieved 2013-03-21.

- ^ Benjamin et al. 1997, pp. 570–571.

- ^ Grubben, G.J.H. (2004). Vegetables. Plant Resources of Tropical Africa. p. 282. ISBN 978-90-5782-147-9.

- ^ Jordan, Michele Anna (2011). California Home Cooking: 400 Recipes that Celebrate the Abundance of Farm and Garden, Orchard and Vineyard, Land and Sea. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 82. ISBN 978-1-55832-597-5.

- ^ Tiwari, B.K.; Brunton, Nigel P.; Brennan, Charles (2012). Handbook of Plant Food Phytochemicals: Sources, Stability and Extraction. John Wiley & Sons. p. 405. ISBN 978-1-118-46467-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Scientists unveil 'supercarrot'". BBC News. 15 January 2008. Retrieved 2013-03-22.

- ^ Greene, Wesley (2012). Vegetable Gardening the Colonial Williamsburg Way: 18th-Century Methods for Today's Organic Gardeners. Rodale. p. 81. ISBN 978-1-60961-162-0.

- ^ "Carrots History" Retrieved on 2009-02-26

- ^ a b US patent 6437222, Irwin L. Goldman and D. Nicholas Breitbach, "Reduced pigment gene of carrot and its use", issued 2002-8-20

- ^ For an overview of the nutritional value of carrots of different colours, see Philipp Simon, Pigment Power in Carrot colour, College of Agricultural & Life Sciences, University of Wisconsin–Madison. Retrieved December 7, 2007.

- ^ Simon et al. (2008), p. 327.

- ^ "FAOSTAT database". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 16 January 2013. Retrieved 2013-03-21.

- ^ Rubatsky et al. (1999), p. 18.

- ^ Bradeen and Simon (2007), pp. 164–165.

- ^ Gist, Sylvia. "Successful Cold Storage". Backwoods Home Magazine. Retrieved 2013-03-21.

- ^ Owen, Marion. "What's Up Doc? Carrots!". UpBeat Gardener. PlanTea. Retrieved 2013-03-21.

Cited literature

- Benjamin, L.R.; McGarry, A.; Gray, D. (1997). "The root vegetables: Beet, carrot, parsnip and turnip". The Physiology of Vegetable Crops. Wallingford, UK: CAB International. pp. 553–80. ISBN 978-0-85199-146-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Bradeen, James M.; Simon, Philipp W. (2007). "Carrot". In Cole, Chittaranjan (ed.) (ed.). Vegetables. Genome Mapping and Molecular Breeding in Plants. Vol. 5. New York, New York: Springer. pp. 162–184. ISBN 978-3-540-34535-0.

{{cite book}}:|editor-last=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ross, Ivan A. (2005). "Daucus carota L.". Medicinal Plants of the World. Chemical Constituents, Traditional and Modern Medicinal Uses. Vol. 3. Springer. pp. 197–221. ISBN 978-1-59259-887-8.

- Rubatsky, V.E.; Quiros, C.F.; Siman, P.W. (1999). Carrots and Related Vegetable Umbelliferae. CABI Publishing. ISBN 978-0-85199-129-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Sharma, Krishnan Datt; Karki, Swati; Thakur, Narayan Singh; Attri, Surekha (2012). "Chemical composition, functional properties and processing of carrot—a review". Journal of Food Science Technology. 49 (1): 22–32. doi:10.1007/s13197-011-0310-7.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Simon, Philipp W.; Freeman, Roger E.; Vieira, Jairo V.; Boiteux, Leonardo S.; Briard, Mathilde; Nothnagel, Thomas; Michalik, Barbara; Kwon, Young-Seok. "Carrot". Vegetables II. Handbook of Plant Breeding. Vol. 2. New York, New York: Springer. pp. 327–357. ISBN 978-0-387-74108-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

Quotations related to Carrot at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Carrot at Wikiquote- Carrot and Garlic Genetics - diverse information on carrots, with links to more (USDA)

Media related to Daucus carota at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Daucus carota at Wikimedia Commons Media related to Carrot-based food at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Carrot-based food at Wikimedia Commons The dictionary definition of carrot at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of carrot at Wiktionary- . The American Cyclopædia. 1879.