Indigenous Australians

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| New South Wales 134,888 Queensland 125,910 Western Australia 65,931 Northern Territory 56,875 Victoria 27,846 South Australia 25,544 Tasmania 17,384 ACT 3,909 Other Territories 233 | |

| Languages | |

| Several hundred indigenous Australian languages (many extinct or nearly so), Australian English, Australian Aboriginal English, Torres Strait Creole, Kriol | |

| Religion | |

| various forms of Christianity, Traditional belief systems based around the Dreamtime | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| see List of Indigenous Australian group names |

Indigenous Australians are the first human inhabitants of the Australian continent and its nearby islands, continuing their presence during European settlement. The term includes the various indigenous peoples commonly known as Aborigines, whose traditional lands extend throughout mainland Australia, Tasmania and numerous offshore islands, and also the Torres Strait Islanders whose lands are centred on the Torres Strait Islands which run between northernmost Australia and the island of New Guinea.

Indigenous Australians use many different terms to describe themselves and their cultures.

Definitions

The term "Indigenous Australians" encompasses a large number of diverse communities and societies, with different modes of subsistence, cultural practices, languages, technologies and inhabited environments. However, these peoples also share a larger set of traits, and are otherwise seen as being broadly related. A collective identity as Indigenous Australians is recognised and exists alongside the identity and membership of many local community and traditional groups.

There are also various names from the indigenous languages which are commonly used to identify groups based on regional geography and other affiliations. These include: Koori (or Koorie) in New South Wales and Victoria; Murri in Queensland; Noongar in southern Western Australia; Yamatji in Central Western Australia; Wangkai in the Western Australian Goldfields; Nunga in southern South Australia; Anangu in northern South Australia, and neighbouring parts of Western Australia and Northern Territory; Yapa in western central Northern Territory; Yolngu in eastern Arnhem Land (NT) and Palawah (or Pallawah) in Tasmania.

These larger groups may be further subdivided; for example, Anangu (meaning a person from Australia's central desert region) recognises localised subdivisions such as Yankunytjatjara, Pitjantjatjara, Ngaanyatjara, Luritja and Antikirinya.

The word aboriginal, appearing in English since at least the 17th century and meaning "first or earliest known, indigenous," has been used in Australia to describe its indigenous peoples as early as 1789. It soon became capitalised and employed as the common name to refer to all Indigenous Australians. Strictly speaking, "Aborigine" is the noun and "Aboriginal" the adjectival form; however this latter is often also employed to stand as a noun. Note that the use of "Aboriginal(s)" in this sense, i.e. as a noun, has acquired negative, even derogatory connotations among some sectors of the community, who regard it as insensitive, and even offensive. The more acceptable and correct expression is "Australian Aborigines," though even this is sometimes regarded as an expression to be avoided because of its historical associations with colonialism. "Indigenous Australians" has found increasing acceptance, particularly since the 1980s.

The Torres Strait Islanders possess a heritage and cultural history distinct from mainland indigenous traditions; the eastern Torres Strait Islanders in particular are related to the Papuan peoples of New Guinea, and speak a Papuan language. Accordingly, they are not generally included under the designation "Australian Aborigines." This has been another factor in the promotion of the more inclusive term "Indigenous Australians."

The once-common abbreviation "Abo" is now widely considered highly offensive, roughly equivalent to "nigger" in the United States. Use of the word "native", common in literature before about 1960, is also regarded as offensive.

Languages

The Australian Aboriginal languages have not been shown to be related to any languages outside Australia (a language that may prove an exception to this is the Eastern Torres Strait language Meriam Mir). Given the time-depth of the occupation of Australia linguists consider it unlikely that any such connections will ever be found[citation needed]. In the late 18th century, there were anywhere between 350 and 750 distinct groupings and a similar number of languages and dialects. At the start of the 21st century, fewer than 200 indigenous languages remain and all but about 20 of these are highly endangered.

Linguists classify Australian languages into two distinct groups, the Pama-Nyungan languages and the non-Pama Nyungan. The Pama-Nyungan languages comprise the majority, covering most of Australia, and is a family of related languages. In the north, stretching from the Western Kimberley to the Gulf of Carpentaria, are found a number of groups of languages which have not been shown to be related to the Pama-Nyungan family or to each other: these are known as the non-Pama-Nyungan languages. While it has sometimes proven difficult to work out familial relationships within the Pama-Nyungan language family many Australianist linguists feel there has been substantial success[1]. Against this some linguists, such as R. M. W. Dixon, suggest that the Pama-Nyungan group, and indeed the entire Australian linguistic area, is rather a sprachbund, or group of languages having very long and intimate contact, rather than a typical linguistic phylum[2].

Given their long occupation of Australia, it has been suggested that Aboriginal languages form one specific sub-grouping. Certainly, similarities in the phoneme set of Aboriginal languages throughout the continent is suggestive of a common origin. A common feature of many Australian languages is that they display so-called mother-in-law languages, special speech registers used only in the presence of certain close relatives. The position of Tasmanian languages is unknown, and it is also unknown whether they comprised one or more than one specific language family, as only a few poor-quality word-lists have survived the impact of colonisation and social dislocation.

History

Origins

Indigenous Australian tradition holds they have always been on the Australian continent.

The scientific view purports that there is no clear or accepted racial origin of the Indigenous people of Australia. Although they migrated to Australia through Southeast Asia they are not demonstrably related to any known Asian or Polynesian population. However, they are closely related to the nearby peoples of Melanesia. There is some speculation that, based on mitochondrial DNA evidence they are related to some racial groups in India. In view of the very long time they have been in Australia (and the Ice Age continent of Sahul), they are almost entirely isolated from other human populations.

Linguistic and genetic evidence shows that there has been long-term contact between Australians in the far north and the Austronesian peoples of modern-day New Guinea and the islands, but that this appears to have been due mostly to trade and some intermarriage.

Migration to Australia

It is believed that first human migration to Australia was achieved when this landmass formed part of the Sahul continent, connected to the island of New Guinea via a land bridge. It is also possible that people came by boat across the Timor Sea. The exact timing of the arrival of the ancestors of the Indigenous Australians has been a matter of dispute among archaeologists. The most generally accepted date for first arrival is between 40,000 - 50,000 years BP. A 48,000 BC date is based on a few sites in northern Australia dated using thermoluminescence. A large number of sites have been radiocarbon dated to around 38,000 BC, leading some researchers to doubt the accuracy of the thermoluminescence technique. Some estimates have been given as widely as from 30,000 to 68,000 BC.[3]

Thermoluminescence dating of the Jinmium site in the Northern Territory suggested a date of 200,000 BC. Although this result received wide press coverage, it is not accepted by most archaeologists. Only Africa has older physical evidence of habitation by modern humans.

Humans reached Tasmania approximately 40,000 years ago by migrating across a land bridge from the mainland that existed during the last ice age. After the seas rose about 12,000 years ago and covered the land bridge, the inhabitants there were isolated from the mainland until the arrival of European settlers[3].

Mungo Man, whose remains were discovered in 1974 near Lake Mungo in New South Wales, is the oldest human yet found in Australia. Although the exact age of Mungo Man is in dispute, the best consensus is that he is at least 40,000 years old. Stone tools also found at Lake Mungo have been estimated, based on stratigraphic association to be about 50,000 years old. Since Lake Mungo is in south-eastern Australia, many archaeologists have concluded that humans must have arrived in north-west Australia at least several thousand years earlier.

Before European settlement

At the time of first European contact, it is estimated that between 250,000 and 1 million people lived in Australia. Population levels are likely to have been largely stable for many thousands of years. The common perception that indigenous Australians were primarily desert dwellers is in fact false: the regions of heaviest Indigenous population were the same temperate coastal regions that are currently the most heavily populated. The greatest population density was to be found in the southern and eastern regions of the continent, the Murray River valley in particular. However indigenous Australians maintained successful communities throughout Australia, from the cold and wet highlands of Tasmania to the more arid parts of the continental interior. In all instances, technologies, diets and hunting practices varied according to the local environment.

Post-colonisation, the coastal indigenous populations were soon absorbed, depleted or forced from their lands; the traditional aspects of Aboriginal life which remained persisted most strongly in areas such as the Great Sandy Desert where European settlement has been sparse.

All Indigenous Australians were hunter-gatherers, while those along the coast and rivers were also expert fishermen. Their mode of life and material cultures varied greatly from region to region. Some Aborigines relied on the dingo as a companion animal, using it to assist with hunting and for warmth on cold nights. While all communities managed their food resources in various sophisticated ways, none practised true agriculture. Some writers have described some Indigenous food and landscape management practices as "incipient agriculture" [citation needed].

In present-day Victoria there were two separate communities with an economy based on eel-farming in complex and extensive irrigated pond systems; one on the Murray River in the state's north, the other in the south-west near Hamilton, which traded with other groups from as far away as the Melbourne area. No Australian animal other than the dingo was domesticated. The typical Indigenous diet included a wide variety of foods, such as kangaroo, emu, wombats, goanna, snakes, birds, many insects such as honey-ants and witchetty grubs. Many varieties of plant foods such as nuts, fruits and berries were also eaten.

A primary tool used in hunting is the spear, launched by a woomera or spear-thrower. Boomerangs were also used. The non-returnable boomerang (known more correctly as a throwing stick), more powerful than the returning kind, could be used to injure or even kill a kangaroo.

In some areas Indigenous Australians lived in semi-permanent villages, most usually in less arid areas where fishing could provide for a more settled existence. Most Indigenous communities were semi-nomadic, moving in a regular cycle over a defined territory, following seasonal food sources and returning to the same places at the same time each year. From the examination of middens, archaeologists have shown that some localities were visited annually by Indigenous communities for thousands of years. In the more arid areas Indigenous Australians were completely nomadic[citation needed], ranging over wide areas in search of scarce food resources.

The Indigenous Australians lived through great climatic changes and adapted successfully to their changing physical environment. There is much ongoing debate about the degree to which they modified the environment. One controversy revolves around the role of Indigenous people in the extinction of the marsupial megafauna (also see Australian megafauna). Some argue that natural climate change killed the megafauna. Others claim that, because the megafauna were large and slow, they were easy prey for human hunters. A third possibility is that human modification of the environment, particularly through the use of fire, indirectly led to their extinction.

Indigenous Australians used fire for a variety of purposes: to encourage the growth of edible plants and fodder for prey; to reduce the risk of catastrophic bushfires; to make travel easier; to eliminate pests; for ceremonial purposes; and just to "clean up country." There is disagreement, however, about the extent to which this burning led to large-scale changes in vegetation patterns.

There is evidence of substantial change in Indigenous culture over time. Rock painting at several locations in northern Australia has been shown to consist of a sequence of different styles linked to different historical periods.

Some have suggested, for instance that the Last Glacial Maximum, of 20,000 years ago, associated with a period of continental wide aridity and the spread of sand-dunes, was also associated with a reduction in Aboriginal activity, and greater specialisation in the use of natural foodstuffs and products. The Flandrian Transgression associated with sea-level rise, particularly in the north, with the loss of the Sahul Shelf, and with the flooding of Bass Strait and the subsequent isolation of Tasmania, may also have been periods of difficulty for affected groups.

Harry Lourandos has been the leading proponent of the theory that a period of hunter-gatherer intensification occurred between 3000 and 1000 BC. Intensification involved an increase in human manipulation of the environment (for example, the construction of eel traps in Victoria), population growth, an increase in trade between groups, a more elaborate social structure, and other cultural changes. A shift in stone tool technology, involving the development of smaller and more intricate points and scrapers, occurred around this time. This was probably also associated with the introduction to the mainland of the Australian dingo.

Indigenous communities also had a very complex kinship structure and in some places strict rules about marriage. In Central Australia, for example, men were required to marry women of a specified degree of cousinage. To enable men and women to find suitable partners, many groups would come together for annual gatherings (commonly known as corroborees) at which goods were traded, news exchanged, and marriages arranged amid appropriate ceremonies. This practice both reinforced clan relationships and prevented inbreeding in a society based on small semi-nomadic groups.

Impact of European settlement

In 1770, Lieutenant James Cook took possession of the east coast of Australia in the name of Great Britain and named it New South Wales. British colonisation of Australia began in Sydney in 1788. The most immediate consequence of British settlement - within weeks of the first colonists' arrival - was a wave of European epidemic diseases such as chickenpox, smallpox, influenza and measles, which spread in advance of the frontier of settlement. The worst-hit communities were the ones with the greatest population densities, where disease could spread more readily. In the arid centre of the continent, where small communities were spread over a vast area, the population decline was less marked.

The second consequence of British settlement was appropriation of land and water resources. The settlers took the view that Indigenous Australians were nomads with no concept of land ownership, who could be driven off land wanted for farming or grazing and who would be just as happy somewhere else. In fact the loss of traditional lands, food sources and water resources was usually fatal, particularly to communities already weakened by disease. Additionally, Indigenous Australians groups had a deep spiritual and cultural connection to the land, so that in being forced to move away from traditional areas, cultural and spiritual practices necessary to the cohesion and well-being of the group could not be maintained. Proximity to settlers also brought venereal disease, which greatly reduced indigenous fertility and birthrates, and alcohol, to which Indigenous Australians had no tolerance. Substance abuse has remained a chronic problem for indigenous communities ever since. The combination of disease, loss of land and direct violence reduced the Aboriginal population by an estimated 90% between 1788 and 1900. Entire communities in the moderately fertile southern part of the continent simply vanished without trace, often before European settlers arrived or recorded their existence. The indigenous people in Tasmania were particularly hard-hit, with the last full-blood indigenous Tasmanian, Truganini, dying in 1876, although a substantial part-indigenous community survived.

Dr Lang said "There is black blood at this moment on the hands of individuals of good repute in the colony of New South Wales of which all the waters of New Holland would be insufficent to wash out the indelible stains." Lang, History of NSW 1834 p.38

A wave of massacres and resistance also followed the frontier of European settlement. In 1838, twenty eight indigenous people were killed at the Myall Creek massacre and the hanging of the white convict settlers responsible was the first time whites had been executed for the murder of indigenous people. Many indigenous communities resisted the settlers, such as the Noongar of south-western Australia, led by Yagan, who was killed in 1833. The Kalkadoon of Queensland also resisted the settlers, and there was a massacre of over 200 people on their land at Battle Mountain in 1884. There was a massacre at Coniston in the Northern Territory in 1928. Poisoning of food and water has been recorded on several different occasions. The number of violent deaths at the hands of white people is still the subject of debate, with a figure of around 10,000 - 20,000 deaths being advanced by historians such as Henry Reynolds. Nevertheless, disease and dispossession were always the major causes of indigenous deaths. By the 1870s all the fertile areas of Australia had been appropriated, and indigenous communities reduced to impoverished remnants living either on the fringes of European communities or on lands considered unsuitable for settlement.

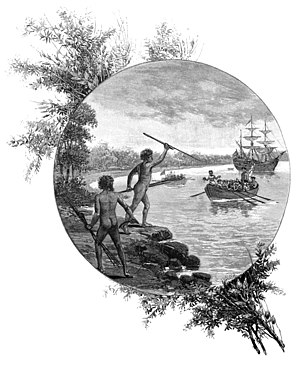

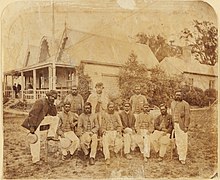

Some initial contact between indigenous people and Europeans was peaceful, starting with the Guugu Yimithirr people who met James Cook near Cooktown in 1770. Bennelong served as interlocutor between the Eora people of Sydney and the British colony, and was the first Indigenous Australian to travel to England, staying there between 1792 and 1795. Indigenous people were known to help European explorers, such as John King, who lived with a tribe for two and a half months after the ill fated Burke and Wills expedition of 1861. Also living with indigenous people was William Buckley, an escaped convict, who was with the Wautharong people near Melbourne for thirty-two years, before being found in 1835. Many indigenous people adapted to European culture, working as stock hands or labourers. The first Australian cricket team, which toured England in 1867, was made up of indigenous players.

As the European pastoral industries developed, several economic changes came about. The appropriation of prime land and the spread of European livestock over vast areas made a traditional indigenous lifestyle less viable, but also provided a ready alternative supply of fresh meat for those prepared to incur the settlers' anger by hunting livestock. The impact of disease and the settlers' industries had a profound impact on the Indigenous Australians' way of life. With the exception of a few in the remote interior, all surviving indigenous communities gradually became dependent on the settler population for their livelihood. In south-eastern Australia, during the 1850s, large numbers of white pastoral workers deserted employment on stations for the Australian goldrushes. Indigenous women, men and children became a significant source of labour. Most indigenous labour was unpaid, instead indigenous workers received rations in the form of food, clothing and other basic necessities. In the later 19th century, settlers made their way north and into the interior, appropriating small but vital parts of the land for their own exclusive use (waterholes and soaks in particular), and introducing sheep, rabbits and cattle, all three of which ate out previously fertile areas and degraded the ability of the land to carry the native animals that were vital to indigenous economies. Indigenous hunters would often spear sheep and cattle, incurring the wrath of graziers, after they replaced the native animals as a food source. As large sheep and cattle stations came to dominate northern Australia, indigenous workers were quickly recruited. Several other outback industries, notably pearling, also employed Aboriginal workers. In many areas Christian missions also provided food and clothing for indigenous communities, and also opened schools and orphanages for indigenous children. In some places colonial governments also provided some resources. Nevertheless, some indigenous communities in the most arid areas survived with their traditional lifestyles intact as late as the 1930s.

In general, the first European colonisers were at least not opposed [citation needed], but there were violent conflicts from time to time frequently culminating in killings. In the Northern Territory, both isolated Europeans (usually travellers) and visiting Japanese fishermen continued to be speared to death occasionally until the start of the Second World War in 1939. It is known that some European settlers in the centre and north of the country shot indigenous people during this period. One particular series of killings became known as the Caledon Bay crisis, and became a watershed in the relationship between indigenous and non-indigenous Australians.

By the early 20th century the indigenous population had declined to between 50,000 and 90,000, and the belief that the Indigenous Australians would soon die out was widely held, even among Australians sympathetic to their situation. But by about 1930 the ruthless process of natural selection imposed on Indigenous Australians by European settlement had run its course. Those who had survived had acquired better resistance to imported diseases, and birthrates began to rise again as communities were able to adapt to changed circumstances.

By the end of World War II, many indigenous men had served in the military. They were among the few Indigenous Australians to have been granted citizenship; even those that had were obliged to carry papers, known in the vernacular as a "dog licence", with them to prove it. However, Aboriginal pastoral workers in northern Australia remained unfree labourers, paid only small amounts of cash, in addition to rations, and severely restricted in their movements by regulations and/or police action. On May 1, 1946, Aboriginal station workers in the Pilbara region of Western Australia initiated the 1946 Pilbara strike and never returned to work. However this protest came as modern technology and management techniques were starting to dramatically reduce the amount of labour required by pastoral enterprises. Mass layoffs across northern Australia followed the Federal Pastoral Industry Award of 1968, which required the payment of a minimum wage to Aboriginal station workers. Many of the workers and their families became refugees or fringe dwellers, living in camps on the outskirts of towns and cities.

The path to reconciliation: 1967 onwards

Indigenous Australians were given the right to vote in Commonwealth elections in Australia in November 1963, and in state elections shortly after, with the last state to do this being Queensland in 1965. The 1967 referendum passed in Australia with a 90% majority which allowed the Commonwealth to make laws with respect to Aboriginal people, and for Aboriginal people to be included when the country does a count to determine electoral representation. This has been the largest affirmative vote in the history of Australia's referenda.

In 1971, Yolngu people at Yirrkala sought an injunction against Nabalco to cease mining on their traditional land. In the resulting historic and controversial Gove land rights case, Justice Blackburn ruled that Australia had been terra nullius before European settlement, and that no concept of Native title existed in Australian law. Although the Yolngu people were defeated in this action, the effect was to highlight the absurdity of the law, which led first to the Woodward Commission, and then to the Aboriginal Land Rights Act.

In 1972, the Aboriginal Tent Embassy was established on the steps of Parliament House in Canberra, in response to the sentiment among indigenous Australians that they were "strangers in their own country". A Tent Embassy still exists on the same site today.

In 1975, the Whitlam government drafted the Aboriginal Land Rights Act, which aimed to restore traditional lands to indigenous people. After the dismissal of the Whitlam government by the Governor-General, a slightly watered-down version of the Act (known as the Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1976) was introduced by the coalition government led by Malcolm Fraser. While its application was limited to the Northern Territory it did grant "inalienable" freehold title to some traditional lands.

In 1992, the Australian High Court handed down its decision in the Mabo Case, declaring the previous legal concept of terra nullius to be invalid. This decision legally recognised certain land claims of Indigenous Australians in Australia prior to British Settlement. Legislation was subsequently enacted and later amended to recognise Native Title claims over land in Australia.

In 1998, as the result of an inquiry into the forced removal of indigenous children (see Stolen generation) from their families, a National Sorry Day was instituted, to acknowledge the wrong that had been done to indigenous families, so that the healing process could begin. Many politicians, from both sides of the house, participated, with the notable exception of the Prime Minister, John Howard.

In 1999 a referendum was held to change the Australian Constitution to include a preamble that, amongst other topics, recognised the occupation of Australia by Indigenous Australians prior to British Settlement. This referendum was defeated, though the recognition of Indigenous Australians in the preamble was not a major issue in the preamble referendum discussion, and the preamble question attracted minor attention compared to the question of becoming a republic (see republicanism in Australia for more details on the 1999 referendum).

Most recently, in 2004, the Australian Government has abolished The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC), which had been Australia's peak indigenous organisation. The Commonwealth cited corruption and in particular, has made allegations concerning the misuse of public funds by ATSIC's chairman, Geoff Clark, as the principal reason. Indigenous specific programs have been mainstreamed, that is, reintegrated and transferred to departments and agencies serving the general population. The Office of Indigenous Policy Coordination has been established within the Department of Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs to coordinate the government-wide effort.

In June 2005, Richard Frankland, founder of the 'Your Voice' political party, in an open letter to Prime Minister John Howard, advocated that the eighteenth-century conflicts between indigenous and colonial Australians "be recognised as wars and be given the same attention as the other wars receive within the Australian War Memorial". In its editorial on 20 June 2005 the Melbourne Age newspaper, said that "Frankland has raised an important question" and asked whether moving "work commemorating Aborigines who lost their lives defending their land … to the War Memorial [would] change the way we regard Aboriginal history."

Issues facing Indigenous Australians today

The Australian Aboriginal population is for the most part urbanised, but a substantial number live in settlements (often located on the site of former church missions) in what are considered remote areas. The health and economic difficulties facing both groups are substantial. Aboriginal people, particularly youths, are 11 times more likely to be imprisoned than the general population, and the rate of suicides in police custody remains quite high.[citation needed] Rates of unemployment, health problems and poverty are likewise higher than the general population; and school retention rate and university attendance is lower.

Health

In 1998-2000, the life expectancy of an Indigenous Australian was 21 years less for males and 20 years less for females than that of an average Australian (Source: ABS). This is attributed to poor health at all levels and all age-groups within the indigenous population (e.g. the indigenous infant mortality rate is four times that of average Australians). However, the primary cause of the problem is unclear, and the discussion of how to solve it generates heated debate. The following factors have been at least partially implicated:

- discrimination

- low income

- poor education

- substance abuse

- remote locations with poor access to health services

- for urbanised Indigenous Australians, social pressures which prevent access to health services

- cultural differences resulting in poor communication between Indigenous Australians and health workers.

Successive Federal Governments have responded to the problem by implementing programs such as the Office of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health (OATSIH). There have been some small successes, such as the reduction of infant mortality since the 1970's, effected by bringing health services into indigenous communities, but on the whole the problem remains unsolved.

Education

Indigenous students as a group leave school earlier, and leave with a lower standard of education, compared to their non-indigenous peers. Although the situation is slowly improving, and the gap narrowing, both the levels of participation in education and training among Indigenous Australians and their levels of attainment remain well below those of non-Indigenous Australians.

The following statistics are taken from the ABS, and mainly refer to 2001 statistics, when the last census was taken.

- 39% of indigenous students stayed on to year 12 at high school, compared to 75% for the Australian population as a whole.

- 22% of indigenous adults had a vocational or higher education qualification, compared to 48% for the Australian population as a whole.

- 4% of Indigenous Australians held a bachelor degree or higher, compared to 21% for the population as a whole. While this fraction is increasing, it is increasing at a slower rate than that for non-Indigenous Australians.

While some of these statistics reflect cultural differences, it has been claimed that they also reflect the poorer quality of some schools in low-income areas, rather than being due to any explicitly discriminatory policies.[citation needed]

In response to this problem, the Commonwealth Government formulated a National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Education Policy. A number of government initiatives have resulted, some of which are listed by the Commonwealth Government's Indigenous Education page.

Crime

An Indigenous Australian is 11 times more likely to be in prison than a non-Indigenous Australian, and in 2003, 20% of prisoners in Australia were Indigenous. (Source: ABS). This does not necessarily translate directly into a higher crime rate by Indigenous Australians; it has been alleged (e.g. John Pilger: A Secret Country) that Indigenous Australians are more likely to be charged and imprisoned for a minor crime than a non-Indigenous Australian. This over-representation of Indigenous Australians in prisons was drawn to public attention by the 1987–1991 Royal Commission into Aboriginal deaths in custody. An Indigenous Australian is twice as likely to be a victim of violence than a non-Indigenous Australian.(Source: ABS).

The causes are debated, but the following factors have been implicated:

- Poverty

- Unemployment

- Poor education

- Reaction against injustice or racism, perceived or otherwise

- Cultural disorientation

Violent crime, in particular domestic and sexual abuse, is rife in many Aboriginal communities. An estimated three in five children have suffered some kind of sexual abuse in the southeast Queensland Aboriginal community of Cherbourg (source: The Australian). In May, 2006, Alice Springs crown prosecutor Nanette Rogers publicly declared child sexual abuse in Aboriginal communities a "National problem" (source: The Australian). Allegations have been made that Aboriginal council and law is more likely to protect the perpetrator than the victim in the case of sexual assault.[citation needed]

Unemployment

According to the 2001 Census, an Indigenous Australian is almost three times more likely to be unemployed (20.0% unemployment) than a non-Indigenous Australian (7.6%). Perhaps surprisingly, the difference is more marked in urban and regional centres than in remote areas, although this needs to be considered in context of lower labour force participation in remote areas and the role of CDEP. (Source: ABS)

Substance abuse

Like many under-privileged communities, a number of Indigenous communities suffer from a range of health and social problems associated with substance abuse of both legal and illegal drugs.

Excessive consumption of alcohol within certain Indigenous communities has been a significant and occasionally high-profile concern, as are the domestic violence and associated issues resulting from the behaviour. A large 2004-05 health survey by the ABS found that the proportion of the Indigenous adult population engaged in 'risky' and 'high-risk' alcohol consumption (15%) was comparable to that of the non-Indigenous population (14%).[4]. One study[5] by the Australian National Commission on Drugs (ANCD) published in 2002 attributes the "public misperception of high alcohol use [in indigenous communities]" to "the disproportionate level of harm caused (to the individual and community) by those drinking at very high levels in public" (ANCD 2002:p.2). Even so, other studies have indicated that those in the Indigenous communities who do drink excessively are at greater risk of harm (to themselves and others) than similar-level alcohol consumers in the wider population[6]

To combat the problem, a number of programs to prevent or mitigate against alcohol abuse have been attempted in different regions, many intiated from within the communities themselves. These strategies include such actions as the declaration of "Dry Zones" within indigenous communities, prohibition and restriction on point-of-sale access, and community policing and licensing. Some communities (particularly in the Northern Territory) have introduced kava as a safer alternative to alcohol, as over-indulgence in kava produces sleepiness, in contrast to the violence that can result from over-indulgence in alcohol. These and other measures have met with variable success, and while a number of communities have seen decreases in associated social problems caused by excessive drinking, others continue to struggle with the issue and it remains an ongoing concern. The ANCD study notes that in order to be effective, programs in general need also to address "...the underlying structural determinants that have a significant impact on alcohol and drug misuse" (Op. cit., p.26).

Petrol sniffing is also an enormous and ever-growing problem among Indigenous communities, the situation being just as serious as alcohol abuse if not worse. Petrol vapour produces euphoria and dulling effect in those who inhale it, and due to its relatively low price and widespread availability, is an increasingly popular substance of abuse. However, petroleum vapour is extremely dangerous to inhale, and will cause permanent damage to the central nervous system and other organs when abused over even a short period of time. Due to the isolation and remote nature of many of the Aboriginal communities in which petrol sniffing is a major issue, the full extent of the problem has only just begun to be appreciated by the wider Australian community. Proposed solutions to the problem are a topic of heated debate among politicians and the community at large. [7][8]

Political inertia and lack of representation

The current and former governments have repeatedly refused to apologise to Aboriginal communities for policies such as that of the stolen generation. In addition, due to corruption and ineffective leadership on the part of its leader, Geoff Clark, ATSIC, the representative body of Aborigine and Torres Strait Islanders, was disbanded and replaced by a network of 30 Indigenous Coordination Centres that administer Shared Responsibility Agreements and Regional Partnership Agreements with Aboriginal communities at a local level.[9]

Mainland Australia

Clans, groups and communities

Before the British colonisation, there were a great many different Aboriginal groups, each with their own individual culture, belief structure, and language. At the time of European settlement there were well over 200 different languages (in the technical linguistic sense of non-mutually intelligible speech varieties)[citation needed]. These cultures overlapped to a greater or lesser extent, and changed over time. Indigenous Australian Aboriginal communities are often called tribes, and there are several hundred in Australia, although the exact number is unknown, because in many parts of Australia, there are no clear tribe, nations or boundaries. The word 'community' is often used to describe Aboriginal groups as a more acceptable word. Sometimes smaller communities are referred to as tribes, and other times many communities are included in the same 'tribe'. Sometimes the different language groups are called tribes, although it can be very difficult to distinguish between different languages and dialects of a single language. The situation is complicated by the fact that sometimes up to twenty or thirty different names (either spelled differently in English, or using a different word altogether) are used for the same tribe or community. The largest Aboriginal communities today are the Pitjantjatjara, the Arrernte, the Luritja and the Warlpiri, all from Central Australia.

Culture

There are a large number of tribal divisions and language groups in Aboriginal Australia, and, corresponding to this, a wide variety of diversity exists within cultural practices. However there are some similarities between cultures. Some definitions follow:

- A Corroboree is a ceremonial meeting of Australian Aborigines.

- Fire-stick farming, identified by Australian archeologist Rhys Jones in 1969, is the practice of using fire to regularly burn vegetation to facilitate hunting and to change the composition of plant and animal species in an area.

- Tjurunga or churinga are objects of religious significance by Central Australian Aboriginal Arrernte (Aranda, Arundta) groups.

- Walkabout refers to the belief of non-Indigenous Australians that Aborigines were prone to "go walkabout" (a pidgin or perhaps quasi-pidgin expression) meaning that they would stop doing their jobs and wander through the bush for weeks at a time. Usually Aborigines were fulfilling ceremonial and spiritual obligations, but could generally not convey this to white station owners, either due to its taboo nature, or the sheer clash of the two cultures which generally left misunderstanding on both sides.

Religion

The 1996 census reported that almost 72 percent of Aborigines practiced some form of Christianity, and 16 percent listed no religion. The 2001 census contained no comparable updated data.[4]

Indigenous Australian's oral tradition and spiritual values are based upon reverence for the land and a belief in the Dreamtime. The Dreaming is at once the ancient time of creation and the present day reality of Dreaming. There were a great many different groups, each with their own individual culture, belief structure, and language. These cultures overlapped to a greater or lesser extent, and evolved over time. The Rainbow Serpent is a major Ancestral being for Aboriginal people across Australia. The Yowie and Bunyip are also well known Ancestral beings.

One version of the Dreaming story runs as follows:

The whole world was asleep. Everything was quiet, nothing moved, nothing grew. The animals slept under the earth. One day the rainbow snake woke up and crawled to the surface of the earth. She pushed everything aside that was in her way. She wandered through the whole country and when she was tired she coiled up and slept. So she left her tracks. After she had been everywhere she went back and called the frogs. When they came out their tubby stomachs were full of water. The rainbow snake tickled them and the frogs laughed. The water poured out of their mouths and filled the tracks of the rainbow snake. That's how rivers and lakes were created. Then grass and trees began to grow and the earth filled with life. [citation needed]

Music

Aborigines developed unique instruments and folk styles. The didgeridoo is commonly considered the national instrument of Australian Aborigines, which has been claimed to be the world's oldest wind instrument. It has possibly been used by the people of the Kakadu region for 1500 years. More recently, Aboriginal musicians have branched into rock and roll, hip hop and reggae. One of the most well known modern bands is Yothu Yindi playing in a style which has been called Aboriginal rock.

Art

Australia has a long tradition of Aboriginal art which is thousands of years old. Modern Aboriginal artists continue the tradition using modern materials in their artworks. Aboriginal art is the most internationally recognisable form of Australian art. Several styles of Aboriginal art have developed in modern times including the watercolour paintings of Albert Namatjira; the Hermannsburg School, and the acrylic Papunya Tula "dot art" movement. Painting is a large source of income for some Central Australian communities such as at Yuendumu today.

Traditional recreation

The Djabwurrung and Jardwadjali people of western Victoria once participated in the traditional game of Marn Grook, a type of football played with possum hide. The game is believed by some to have inspired Tom Wills, inventor of the code of Australian rules football, a popular Australian winter sport. Similarities between Marn Grook and Australian football include the unique skill of jumping to catch the ball or high "marking", which results in a free kick. The word "mark" may have originated in "mumarki", which is "an Aboriginal word meaning catch" in a dialect of a Marn Grook playing tribe. Indeed, Aussie Rules has seen many indigenous players at elite football, and have produced some of the most exciting and skillful to play the modern game. Approximately one in ten AFL players are of indigenous origin. [5] The contribution the Aboriginal people have made to the game is recognised by the annual AFL "Dreamtime at the 'G" match at the Melbourne Cricket Ground between Essendon and Richmond football clubs (the colours of the two clubs combine to form the colours of the Aboriginal flag, and many great players have come from these clubs, including Essendon's Michael Long and Richmond's Maurice Rioli). Testifying to this abundance of indigenous talent, the Aboriginal All-Stars are an AFL-level all-Aboriginal football side competes against any one of the Australian Football League's current football teams in pre-season tests. The Clontarf Foundation and football academy is just one organisation aimed at further developing aboriginal football talent.

See the comprehensive study of Aboriginal people in sport: Aborigines in sport by Colin Tatz

Tiwi Islands and Groote Eylandt

The Tiwi islands are inhabited by the Tiwi, an Australian Aborigine people culturally and linguistically distinct from those of Arnhem Land on the mainland just across the water. They number around 2,500. Groote Eylandt belongs to the Anindilyakwa Aboriginal people, and is part of the Arnhem Land Aboriginal Reserve.

Tasmania

The Tasmanian Aboriginals are thought to have first crossed into Tasmania approximately 40,000 years ago via a land bridge between the island and the rest of mainland Australia during an ice age. The original population, estimated at 8,000 people was reduced to a population of around 300 between 1803 and 1833 mainly due to the actions of white settlers. Almost all of the Tasmanian Aboriginal peoples today are descendants of two women: Fanny Cochrane Smith and Dolly Dalrymple. A woman named Truganini, who died in 1876, is generally considered to be the last full blooded Tasmanian aborigine.

Torres Strait Islanders

Between 6% and 10% of Indigenous Australians identify themselves as Torres Strait Islanders. There are more than 100 islands which make up the Torres Strait Islands where they come from. There are 6,800 Torres Strait Islanders who live in the area of the Torres Strait, and 42,000 others who live outside of this area, mostly in the north of Queensland, such as in the coastal cities of Townsville and Cairns. Many organisations to do with Indigenous people in Australia are named "Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander", showing the importance of Torres Strait Islanders in Australia's indigenous population. The islands were annexed by Queensland in 1879. The Torres Strait Islanders were not given official recognition by the Australian government until the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission was set up in 1990. Eddie Mabo is from Murray Island in the Torres Strait, which the famous Mabo decision of 1992 involved.

Population

As at June 2001, the Australian Bureau of Statistics estimated the total resident indigenous population to be 458,520 (2.4% of Australia's total), 90% of whom identified as Aboriginal, 6% Torres Strait Islander and the remaining 4% being of dual Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander parentage.

In the 2001 census the Aboriginal population in different States was:

- New South Wales - 134,888

- Queensland - 125,910

- Western Australia - 65,931

- Northern Territory - 56,875

- Victoria - 27,846

- South Australia - 25,544

- Tasmania - 17,384

- ACT - 3,909

- Other Territories - 233

While the State with the largest total Aboriginal population is New South Wales, as a percentage this constitutes only 2.1% of the overall population of the State. The Northern Territory has the largest Aboriginal population in percentage terms for a State or Territory, with 28.8%. All the other States and Territories have less than 4% of their total populations identifying as Aboriginal; Victoria has the lowest percentage (0.6%). The populations in the eastern states are more likely to be urbanised sometimes in city communities such as at Redfern in Sydney, whereas many of the populations of the western states live in remote areas, closer to a traditional Aboriginal way of life.

Prominent Indigenous Australians

There have been many distinguished Indigenous Australians, in politics, sports, the arts and other areas. These include senator Neville Bonner, olympic athlete Cathy Freeman, tennis player Evonne Goolagong, Australian rules footballer Michael Long, rugby union legend Mark Ella, actor Ernie Dingo, painter Albert Namatjira, singer Christine Anu and many others.

See also

Listed alphabetically:

- Aboriginal deaths in custody

- Bindibu Expedition

- Day of Mourning

- Gurindji strike

- History wars

- Jandamarra, a Bunuba man who resist European occupation

- List of English words of Australian Aboriginal origin

- Message stick

- List of Australian Aborginal massacres

- Prominent indigenous Australians

- Roderick Flanagan "The Aborigines of Australia" George Robertson and Co, Sydney, 1888 and reprinted 1988 by Boolarong Publications, Mosman, Queensland

- Stolen Generation

- Yolngu

- European Network for Indigenous Australian Rights

- UNPO (Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organisation)

References

- ^ Bowern, Claire and Harold Koch (eds.). 2004. Australian Languages: Classification and the comparative method. John Benjamins, Sydney.

- ^ Dixon, R.M.W. 1997. The Rise and Fall of Languages. CUP.

- ^ Mulvaney, John and Johan Kamminga. 1999. Prehistory of Australia. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington.

- ^ Australian Statistician (2006). "National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey, 2004-05 (ABS Cat. 4715.0), Table 6" (PDF). pdf. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 2006-06-01.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help). Based on age-standardised data. The percentage-point difference between the two figures quoted is not statistically significant, and a similar result was obtained in the earlier 2000-01 survey. The definition of "risky" and "high-risk" consumption used is 4 or more standard drinks per day average for males, 2 or more for females. - ^ Australian National Commission on Drugs (2002). "ANCD Report into Cape York Indigenous Issues" (PDF). pdf. Retrieved 2006-06-01.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) (2005). "National Drug Strategy Household Survey - detailed findings" (PDF). pdf. Retrieved 2006-06-01.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help), p.32 et. seq. - ^ [1]

- ^ [2]

- ^ "Coordination and engagement at regional and national levels". Administration. Office of Indigenous Policy Coordination. 2006. Retrieved 2006-05-17.

External links

Listed alphabetically:

- ABC Message Stick Indigenous News Online

- ABC Message Stick Indigenous Gateway

- Aboriginal Links International - Australian Links

- Aboriginal Studies WWW Virtual Library

- ABS Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population

- ABS estimates

- National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Education Website

- Bibliography for Aboriginal Studies

- Convict Creations ("revisionist" pov)

- DFAT Australia's Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples

- Department of Immigration, Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs

- European Network for Indigenous Australian Rights

- Indigenous Australia - Australian Museum educational site

- KooriWeb

- Norman B. Tindale's Catalogue of Aboriginal Tribes