Wikipedia:Reference desk/Science

of the Wikipedia reference desk.

Main page: Help searching Wikipedia

How can I get my question answered?

- Select the section of the desk that best fits the general topic of your question (see the navigation column to the right).

- Post your question to only one section, providing a short header that gives the topic of your question.

- Type '~~~~' (that is, four tilde characters) at the end – this signs and dates your contribution so we know who wrote what and when.

- Don't post personal contact information – it will be removed. Any answers will be provided here.

- Please be as specific as possible, and include all relevant context – the usefulness of answers may depend on the context.

- Note:

- We don't answer (and may remove) questions that require medical diagnosis or legal advice.

- We don't answer requests for opinions, predictions or debate.

- We don't do your homework for you, though we'll help you past the stuck point.

- We don't conduct original research or provide a free source of ideas, but we'll help you find information you need.

How do I answer a question?

Main page: Wikipedia:Reference desk/Guidelines

- The best answers address the question directly, and back up facts with wikilinks and links to sources. Do not edit others' comments and do not give any medical or legal advice.

June 20

Objections to “The Butterfly Effect”

What I find problematic with the notion of something like a butterfly flapping its wings and initiating major changes in, say, storm patterns is that while such an event is possible, it is very unlikely. Steve Baker, along with most commentators who use this example, seem to imply that every such small phenomenon leads to massive changes later on. The prime cinematic depiction of this notion can be found in the film Run Lola Run in which Lola runs on a desperate cause. Three variations of the run are shown (as if they were “sideways in time” to each other) and very small changes in the way events unfold have major changes in what eventuates. My problem with this lies in that I don’t think that our lives work like that. For example, for 12 years I lived in an apartment, and walked, shopped, ate out, took trains to the city and the beach, and so on. On some days, I would meet a friend and spend hours drinking and talking to them, on other days, I might forget something and have to go back home to retrieve an item. But each day, even if there were divergences, ended up pretty much the same. I came home and went to bed. Of course, there was an occasional event which DID change my life. On one occasion, I was invited to a party and there I got into a long and delightful conversation with a lovely lady who became my wife. Here was an example of a small deviation in my usual path which led to major changes. But here is the point: there were countless thousands of such small deviations from the normal, and none of the others led anywhere. If all or most of these changes DID lead to major changes, then I cannot even begin to see how my life, or anyone’s life, could begin to proceed. Every day would involve major departures from what had gone before. It would be like some kind of existential hurricane, with events thrown around so chaotically that nothing could make sense. A bit like some hyperkinetic music video.

So, I think that the “Butterfly Effect” can occur, but it is an exceptional event. Indeed, it is difficult to see how any meteorological phenomena could be predicted at all if it was infinitely sensitive to all such small events. For every butterfly who initiates a storm, there are billions of butterflies that do not, just as, in my own and your lives, there are millions of small events which do not affect our lives beyond their brief span. In the case of Run Lola Run, I have no problem with the idea that one such small change in the initial conditions could lead to major change in the outcome. What I find problematic is the clear inference in the film that ALL such small deviations will lead ineluctably to major qualitative changes in the outcome.

With regards to the scenario that an insect being clobbered in the past might lead to, say, lizard people dominating the future (so well-satirized by The Simpson's), well, I just don't buy it. Surely, there is a sturdier structure to evolution that would be not be vulnerable to every such small deviation. Perhaps, as in my own life, small deviations from the norm have effects which are visible for a while, but then, like ripples in a stream, become progressively weaker as time moves on - a case where some overcompassing logic of evolution makes itself felt. What say you? Myles325a (talk) 06:58, 20 June 2016 (UTC)

- No. It is the sum of everything that occurs in the atmosphere that causes a hurricane in the far future. Millions of other butterflies each have the power to singlehandedly stop it or start it, delay it, advance it, move it left or move it right, make it weaker or stronger. If half the butterflies of Earth did the best possible things to stop New Orleans from being damaged in 2005 at a time when most of them could do it singlehandedly and half did the opposite, trying to hurt it and they all started and stopped intervening at exactly the same time I suppose they would balance out and nothing would change. I believe every time you burp the air movement causes many hurricane deaths many years from now and prevents an equal number. Theoretically you could even be simultaneously saving the same person from one hurricane and condemning him to death in another, all because of a burp. It's just random weather. But the random has to come from somewhere. Who knows where it ends. Maybe the chain of causation continues all the way down to quantum mechanical fluctuations, which would cause hurricanes but are utterly powerless to noticeably change any weather less than a certain amount of time in advance. Sagittarian Milky Way (talk) 09:27, 20 June 2016 (UTC)

- I think you are confusing two different issues. The Butterfly effect is about the inter-connectedness of the the environment: comparatively small events in one place can start a series of events which result in much more dramatic events somewhere else. It should be seen as a metaphor, not as a literal description of the effect one butterfly can have.Most of what you are talking about concerns alternative realities: what might have happened if you, or anyone else, had done something slightly differently. The fact that you did things differently on different days is beside the point - what you have actually done is your actual reality. What your life might have been like if you had done something differently is the realm of alternate reality. What if your car had broken down and you had missed that party and never met your wife? What if the day you were late for work because you had to go back for something you forgot was the day your boss was deciding who to promote - and he picked someone else because you turned up late? Those things are unknowable - but make good fiction! Wymspen (talk) 10:22, 20 June 2016 (UTC)

- Edward Lorenz coined the term Butterfly effect for the sensitive dependence on initial conditions in which a small change in one state of a deterministic nonlinear system can result in large differences in a later state. Chaos theory is the study of such sensitive systems. The OP raises a Straw man objection to Lorenz' observation by representing it as having real predictive power, saying this butterfly wing causes that hurricane. In reality chaos theory identifies many systems (including weather) where the consequences of even a tiny initial change can never be said to have finally played out. AllBestFaith (talk) 12:07, 20 June 2016 (UTC)

- This popular fantasy seems like another way of saying "For Want of a Nail..." ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 13:56, 20 June 2016 (UTC)

- You're right, not every small change leads to big differences. But some can. And we can't know ahead of time which are which. What you're picking up on is the general stability of major ecosystems and human societies over scales roughly equal to human life spans. The funny thing about chaotic systems is that they can spend a very long time doing roughly the same types of things, and aren't very "random" at all. Keep in mind we are talking about deterministic chaos when we speak of the butterfly effect. I highly recommend this book [1], At home in the universe. It's ostensibly about abiogenesis, but a recurring theme is that life is sort of on the edge of chaos - too much chaos is too little conserved structure, and nothing can manage to reproduce. But too much stasis in a system makes it frozen and non-living. Anyway, it really is good, and touches upon some very relevant issues of what chaos means for biological systems.

- Finally, keep in mind there are sort of different degrees of chaos. If the Lyapunov exponent is just barely above 1, then the system may look very regular and predictable, and may in fact be highly locally stable. But with a very large Lyapunov exponent, we get something like the hyperkinetic music video you describe. And all of this comes with a caveat based on mathematical models. All the top scientists agree that the weather systems are best modeled as chaotic. But the butterfly effect is technically a statement about a system of equation, not about the world. And the extent to which truths about equation are truths about the world is a tough topic in its own right ;) SemanticMantis (talk) 15:40, 20 June 2016 (UTC)

Pompeii sink faucet

In old Pompeii main street one can see several ancient stone sinks, some of them ‘modernized’ with a new metal faucet. What is the correct archaeological term that describes such a process? Etan J. Tal(talk) 08:30, 20 June 2016 (UTC)

- The words used by most archaeologists to describe such a practice would not be acceptable in print. Wymspen (talk) 09:20, 20 June 2016 (UTC)

- Bastardized might be the word in question here. Pretty much the only acceptable case for adding modern materials to ancient objects is to preserve them, such as all the things done to the Leaning Tower of Pisa to prevent it from falling over. StuRat (talk) 15:02, 20 June 2016 (UTC)

- The term is Renovation. --Jayron32 12:12, 20 June 2016 (UTC)

- "Modernization" is an accurate term, but has a positive meaning. For a neutral or negative meaning, perhaps "altered" might be how an antiques dealer would describe it, or "married", in the case where 2 different items are combined, such as the ancient sink and modern faucet (Wiktionary lacks this def, so here's an article that uses it: [2]). StuRat (talk)

- Thank you for your cooperarion. Here is the photo with its present caption.

Etan J. Tal(talk) 05:58, 21 June 2016 (UTC)

- 'Professional ignorance'? Etan J. Tal(talk) 06:24, 21 June 2016 (UTC)

- Vandalism isn't the proper word, as that would mean it was done just to damage the object, while the purpose was to make it more useful, and the damage was incidental. I have seen the term misused in this way before though, such as when somebody spray paints "art" on a building without the owner's permission. That may well be illegal, but it isn't vandalism, since their purpose was not to cause damage. StuRat (talk) 13:47, 21 June 2016 (UTC)

- Agree. Etan J. Tal(talk) 13:53, 21 June 2016 (UTC)

- Faucetization--178.103.190.96 (talk) 04:23, 23 June 2016 (UTC)

Fauna with High body temperature

Please any body tell me that what is the name of animal that has highest body temperature. please mention the temperature also. — Preceding unsigned comment added by Achyut Prashad Paudel (talk • contribs) 09:05, 20 June 2016 (UTC)

- I'm not sure, but this will probably be one of the bird species, as their metabolism must be extremely fast in order to provide enough energy for flying. 67.164.54.236 (talk) 09:31, 20 June 2016 (UTC)

- A 1991 paper states "The highest Tb [deep body temperature] ever recorded from a bird was 47.7C" DrChrissy (talk) 20:42, 20 June 2016 (UTC)

- Look at bats too. Andy Dingley (talk) 11:34, 20 June 2016 (UTC)

- Thanks for the prompt Andy. After making my comment about goats below, I had a quick look at bats (which of course are also mammals). It appears they have a quite different approach to thermoregulation to other heterotherms. Have a look at the abstract of this paper [3], particularly paragraph 6. DrChrissy (talk) 20:50, 20 June 2016 (UTC)

- Not really my field anyway, but sorry for my rushed note this morning. AIUI, a simple statement "resting temperature and metabolic rate is dependent on the ambient temperature" doesn't hold true for the tree-roosting fruitbats anyway, as they are larger, have a rather different approach to thermoregulation from the smaller bats and their roost habitat is also more variable in temperature. Where I picked this up was in relation to the recent ebola epidemic, where the unusual metabolism and high temperature of bats was seen to be a significant factor (or maybe not). Andy Dingley (talk) 23:22, 20 June 2016 (UTC)

- Thanks for the prompt Andy. After making my comment about goats below, I had a quick look at bats (which of course are also mammals). It appears they have a quite different approach to thermoregulation to other heterotherms. Have a look at the abstract of this paper [3], particularly paragraph 6. DrChrissy (talk) 20:50, 20 June 2016 (UTC)

- You didn't specify if you just mean warm-blooded animals (endotherms) or if animals who get their heat from the environment are also okay (ectotherms). The Pompeii worm is an animal that colonizes deep sea hydrothermal vents and comfortably lives at temperatures of 80 °C (176 °F). Water bears (tardigrades) are claimed to be even more tolerant, and capable of surviving short exposures to temperatures up to 150 °C (302 °F), but those experiments are artificial and wouldn't constitute a natural living environment like we see with the worms. Dragons flight (talk) 09:45, 20 June 2016 (UTC)

- For warm blooded animals, can anyone beat the 116 °F (47 °C) of the Scimitar-horned Oryx?--Phil Holmes (talk) 12:54, 20 June 2016 (UTC)

- An even better question is, who inserted the rectal thermometer? μηδείς (talk) 20:15, 20 June 2016 (UTC)

- Phil, I always thought that goats had the highest body temperature of the mammals, and sure enough, I trump your 37°C with 38.7°C.[4] Before we get carried away with this, it is important to realise the site at which the body temperature is measured is terribly important; it varies by a surprising amount depending on the location. DrChrissy (talk) 20:30, 20 June 2016 (UTC)

- For warm blooded animals, can anyone beat the 116 °F (47 °C) of the Scimitar-horned Oryx?--Phil Holmes (talk) 12:54, 20 June 2016 (UTC)

Chemical Splitting of Methane gas

At what temperature Methane Splits into its constituent?(Say the lowest one) — Preceding unsigned comment added by Achyut Prashad Paudel (talk • contribs) 09:15, 20 June 2016 (UTC)

- According to this paper, methane breaks down into hydrogen and acetylene at ~1230°C: 2CH4 → C2H2 + 3H2. (Note that elemental carbon is NOT produced in this reaction.) 67.164.54.236 (talk) 09:40, 20 June 2016 (UTC)

Refractometry

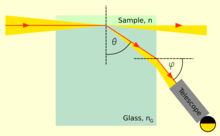

How do they measure the index of refraction (and the birefringence, if any) of opaque gems such as turquoise? Is there a special technique for this? 67.164.54.236 (talk) 09:29, 20 June 2016 (UTC)

- The Refractive index of a material can be found by placing it in contact with a liquid of known lower refractive index and measuring the critical angle . This needs only a very thin slice of a translucent gemstone and may also be done at non-visual wavelengths such as Infrared for which the material may be transparent. See Refractive index#Homogeneous media. AllBestFaith (talk) 11:32, 20 June 2016 (UTC)

- Thanks! So they use a very thin slice to let the light through, right? 67.164.54.236 (talk) 22:03, 20 June 2016 (UTC)

Wheel bug nymph

In our article on wheel bugs, we give a photo of a wheel bug nymph with a red abdomen (and most other Google Image search pictures online show this too). However, the University of Kentucky's entomology website here [5] shows the nymph having a white abdomen, which is the kind I have seen near my house (in Kentucky). Is this a particular subspecies or variety, or have we misidentified something else? shoy (reactions) 16:33, 20 June 2016 (UTC)

- Yeah they usually/often have red abdomens, warning coloration I think. Then again there's lots of variation [6]. I think this is within the range of within-species variation. The nymphs go through different instars, and the adults don't have red abdomens, so some instar should look like a nymph but have a less-red abdomen, right?

- For greater certainty that actual wheel bug nymphs have red abdomens, see page 62 in this journal article [7] that clearly describes them as having red abdomens. It is also possible that you are mis-identifying some other Hemipteran nymph - just recently I made the mistake of thinking some leaf-footed bug nymphs were assassin bugs :) I was not able to find any info on any recognized subspecies/varieties of wheel bugs, but I didn't try that hard. SemanticMantis (talk) 17:19, 20 June 2016 (UTC)

5 GHZ vs 2,4 GHZ wlan

if I use the 5 ghz is it more healthy because there is less radiation? If I use 5 ghz, does my mobile phone device has 0,00001% more power because it is easier for it to hold the wlan connection or does it use 0,000001% more power per day to be connected to the internet? --Ip80.123 (talk) 20:30, 20 June 2016 (UTC)

- No non-thermal relationship between wireless electronic devices and health has been satisfactorily demonstrated -- if your phone's wifi antenna isn't hot enough to burn you, then it's not hurting you. No conceivable test could usefully distinguish a difference in cell phone power consumption on the order of 0.000001%. 5 GHz and 2.4 GHz bands are primarily distinguished by speed (5 GHz is faster) and range (2.4 GHz is available farther); those are the criteria you should be using to decide what you connect with. — Lomn 22:42, 20 June 2016 (UTC)

- Although "less radiation" is very vague, a 5 GHz transmission has more energy per photon than a 2.4 GHz one, not that this has much practical significance unless you're designing hardware. --71.110.8.102 (talk) 02:42, 21 June 2016 (UTC)

Dear 71.110.8.102, are you sure with this proton theory? I have seen a youtube video where a guy has put his wlan router inside the microwave to see if there still comes the wlan signal out of it and the signal of the 5GHZ was from 100% down to 3% and the wlan of 2,4 has been lowered from 100% signal down to 20%, so it seems that the 2,4 is more powerful..--Ip80.123 (talk) 18:15, 21 June 2016 (UTC)

- The higher the frequency the more it behaves like light. Less intrusion into objects, more coverage is based refexion and more locations of phase cancellation. --Hans Haase (有问题吗) 19:37, 21 June 2016 (UTC)

- Yes, this is Modern Physics 101. I provided a link to our article on photons, which explains this in depth. Radio waves can penetrate walls while visible light, which has a higher frequency, is blocked, which contradicts your assumption. This is a deep topic—trying to explain light's behavior was one of the primary motivations for the development of quantum mechanics—and there's plenty to dive into if you want to learn more. --71.110.8.102 (talk) 20:31, 21 June 2016 (UTC)

- The behavior of microwaves and terahertz radiation can be surprising. Different frequencies penetrate materials differently. There have actually been applications using terahertz to tell which bacteria are in the air (e.g. anthrax) based on absorption by their DNA. And of course, absorption by their DNA should be of interest! The radiation cannot break bonds, but can it displace a transcription factor with interesting effects? I would guess it depends on the frequency. Wnt (talk) 00:19, 22 June 2016 (UTC)

June 21

When will a F-35 be fully ready? Why does the USS Gerald Ford take so long to deploy?

The article doesn't say on the first one and says she'll spend 2016-2019 doing.. something on the second. Why does it take 3 years between being commissioned into the Navy and being deployed? The 2005 article said the F-35 will enter service in... 2008. Sagittarian Milky Way (talk) 00:41, 21 June 2016 (UTC)

- For the F-35, it depends on what you mean by "fully ready". The F-35B is currently at initial operating capability with the USMC and is deployed with VMFA-121. Deliveries are currently scheduled for the next 20 years; undoubtedly, the aircraft will receive upgrades during that time (it's the case with all other major aircraft). Service life is anticipated for another 35 years beyond that; undoubtedly, the aircraft will receive upgrades then, too. Full operational capability is currently forecast for 2021 per several search results, but that definition means (among other thing) "all units scheduled to receive a system have received it" -- is that a precursor to say that the aircraft is "fully ready" by your standards?

- For the USS Gerald Ford, I'm doing more guesswork, but I suspect the long working-out process is because this is the USN's first new class of carrier in about 45 years (depending on where you want to snap the line on the USS Nimitz) — the gap between the Ford and the Nimitz is the same as that between the Nimitz and the USN's first fleet carrier, the USS Lexington. Per the Ford's article, there's a lot of testing to wring out all of the new tech so that future ships in the class don't have the same growing pains. — Lomn 02:03, 21 June 2016 (UTC)

- When will testing finish on at least one variant and the first individual aircraft go "on duty" and have all its version 1.0 capability available to be used within about whatever the in service scrambling time's supposed to be? No taking an extra hour cause "Oh shit, it's not fueled, the non-trainers weren't supposed to be fueled for another 3 months, somebody get a fuel truck! Who here has finished training? Somebody arm the weapons! Find the guy with the other arming key!..." (however unlikely it is that we'd be threatened by something that needs an F-35 that early in the product lifecycle) Sagittarian Milky Way (talk) 05:55, 21 June 2016 (UTC)

- The problem with the Ford deploying is... μηδείς (talk) 12:41 am, Yesterday (UTC−4)

- Ah, I didn't realize the infobox's "status: testing, training" only means the A & C are testing and they don't have a B to spare from training (with the F-35 pilot cadre growing for decades and low immediate battlefield need and all). I guess it's happened already then. Sagittarian Milky Way (talk) 21:01, 21 June 2016 (UTC)

How to label a 0 distance in an engineer drawing

Let's say I have a starting raw material that looks like the first frame[8]. If I want the left half to be machined so that it's 10 units higher than the right half, I would draw it like the second frame.

But what about the case when that distance is 0? As in, I want the left half to be flush with the right half like the third frame? How do I draw that? Any similar example would be welcome. Johnson&Johnson&Son (talk) 01:44, 21 June 2016 (UTC)

- have a look at these examples. I'm not sure there is precisely such a thing as you are asking, I think you would simply include the dimension on the side as normal and an axis line, to make it clear you could include a "right angle" mark in the corner of the object and then if you've drawn a straight line, it's assumed the line is straight. If you want to you could probably include a dimension on both sides, but I don't think it's necessary. You could draw a "ghost" of where the material you need removed is, with the original dimension. Vespine (talk) 02:22, 21 June 2016 (UTC)

- Thanks for the help.

- >I think you would simply include the dimension on the side as normal and an axis line

- >If you want to you could probably include a dimension on both sides

- I cannot dimension the left side against the bottom nor the right side against the bottom due to variation of the material. I would love to if I could, but I can't, hence the tricky problem.

- I can only dimension the left side with respect to the right side. Johnson&Johnson&Son (talk) 03:11, 21 June 2016 (UTC)

- Basically imagine the bottom as a rough irregular shape like this[9], impossible to reference against.

- But I do have a nice flat repeatable reference surface, which is the right side. So I'm forced to rely on only referencing against it and nothing else. Johnson&Johnson&Son (talk) 03:16, 21 June 2016 (UTC)

- It's rather unusual to mill both sides down independently when you want them both to be flush, as this process is likely to leave a discontinuity between them. But, if this is the only machining possible, an engineering note, perhaps with leaders pointing to both sides, might be in order. It could say something like "Mill both sides flush to each other and sand out any discontinuity." StuRat (talk) 04:40, 21 June 2016 (UTC)

- Only the left side is milled. The right side is simply the shape of the stock. It's like a L channel.

- How would the leaders look like? If you don't mind, could you please take a screenshot or even just make a rough paint drawing like mine would be fine.Johnson&Johnson&Son (talk) 05:58, 21 June 2016 (UTC)

- That's a fairly useless suggestion if you are dealing with a professional machine shop, they could quite rightly charge you ten thousand dollars for that. The correct solution is to define the 'as is' surface as a reference plane, and then define the machined plane relative to that using the appropriate tolerance form and value, depending on what you need from the machined surface. http://www.gdandtbasics.com/parallelism/ would be a place to start, but you could just apply a flatness tolerance to the entire contiguous surface, ie bothte machined and unmachined parts. Greglocock (talk) 07:16, 21 June 2016 (UTC)

- Here's some examples: [10] (straight leader lines, at low resolution, unfortunately), [11] (curved leader lines). The note can either be placed directly, or a number can be placed there, and circled. That number then references a note on either the side of that page or on another page. StuRat (talk) 13:59, 21 June 2016 (UTC)

Voltaic Cell

Hello, I am having trouble wrapping my head around the chemistry/physics behind lead-acid batteries. A textbook I'm reading tells me that in a battery (which is not hooked up to anything) maintains a potential difference (the cell potential difference, determined entirely by the chemical's redox potentials). It does so by having the following half-cell reactions occur on the electrodes, which again are not in contact (except by the electrolyte):

(anode)

(cathode)

I have two questions:

- I would say, if the reaction were to theoretically start on the anode, then the anode reaction makes perfect sense; the reaction will produce two electrons that travel through the lead metal, and end up at the terminal. However, the positive and negative terminals are not in contact; my question is then, where do the 2 electrons come from on the cathode reaction? I have tried to come up with a reaction mechanism for how these two electrons could have perhaps come from the electrolyte, but I am stumped.

- Say the cell is at its cell potential difference, with the electrons at the anode terminal and the deficit of electrons on the cathode terminal. If the battery were to be attached to a load, would it be more correct to say that the battery "produces a force" that moves the electrons (from within the wire) through the circuit, or would it be more correct to say that the excess electrons originally on the anode terminal move through the circuit instead?

Thanks for the help. 74.15.5.167 (talk) 03:29, 21 June 2016 (UTC)

- Does this answer your question ? The cathode and the anode ARE in contact, through the electrolyte. Vespine (talk) 04:35, 21 June 2016 (UTC)

- Elecrons travel from anode to cathode through the load by wires (when there is one). The battery produces the electromotive force. Ruslik_Zero 17:23, 21 June 2016 (UTC)

- Okay, but does that mean there is no chemical reaction that transfers these electrons through the electrolyte? That is, it sounds to me like, if the battery was not hooked up to any load or wires, then the anode could produce its chemical reaction but the cathode could not (as it requires the anode's electrons). Would that not imply that a battery on its own has no potential difference if it weren't hooked up to a load? 74.15.5.167 (talk) 23:59, 21 June 2016 (UTC)

- Elecrons travel from anode to cathode through the load by wires (when there is one). The battery produces the electromotive force. Ruslik_Zero 17:23, 21 June 2016 (UTC)

- The key thing to grok here is that electrons carry a LOT of charge. So an undetectable shift in the proportion of how many + ions and how many - ions are in a given part of a solution adds up to a huge change in voltage. This is how an electrolyte works - the ions can simply move back and forth. They can "brigade", too - if one negative ion moves a few angstroms one way, and the next one down the line does the same, and the one after that... all the way to the far end of the electrolyte, then the charge effectively moves long before any one ion could ever cross the distance. So in practice, you have an electrolyte with a certain voltage here and there within it, and that is putting an electromotive force on the ions, and you can measure that in aggregate without tracing a single completed motion that takes the electron from one end to the other.

- Now the battery therefore can have a difference in charge without having any noticeable effect on how many electrons or lead ions are present at each end, because only an undetectably tiny fraction have to change before there is a voltage difference. Once there is a voltage difference, that difference is pushing back against the electrons, against the electrolyte, so that the equilibrium no longer favors any further reaction at either end. I think -- I might be saying more than I know about this part, because there's a distinction between discharging and recharging a non-rechargeable battery and simply having it sit on a shelf. I think this is because the equilibrium occurs at a very small scale, whereas discharging the battery substantially creates macroscopic (or at least microscopic) changes in its structure. Wnt (talk) 00:10, 22 June 2016 (UTC)

Freezing water and oil

What aspect has the solid obtained by freezing an emulsion of water and oil? Are the oil bubbles traped in ice? What is the difference from the case of two distinct layers of water and oil? Does the heat transfer between layers of water and oil play affect the structure of the solid obtained?--5.2.200.163 (talk) 15:36, 21 June 2016 (UTC)

- It depends on the type of emulsion and how it is frozen. It seems pretty complicated. Here are two research articles about the freezing of oil/water emulsions [12] [13]. Here's [14] another that is freely accessible. SemanticMantis (talk) 17:05, 21 June 2016 (UTC)

In the scientific name Sus scrofa L., what does the L. denote?

I would like to include the sub-species of wild boar found in the UK at the Wild boar article. This article[1] states that it is Sus scrofa L. What does the L. denote? DrChrissy (talk) 20:20, 21 June 2016 (UTC)

- Naming authority, i.e. described the species, and often who gave it the name that is being used. By convention, a simple 'L.' means the big guy, Linneaus himself. Kind of surprising at first how many things he got his mitts on, even from around the world. This is the simplest usage, there are all kinds of arcane variants supported by formal ICN/ICZN policy, but I don't see anyone other than systematists/taxonomists using those much. There are ways to describe who described it, who renamed it, and then how the genus was moved into another family, but that's way above my pay grade. Altogether a commonly confusing thing, one that's surprisingly hard to figure out if you can't just ask someone what's up :) SemanticMantis (talk) 20:23, 21 June 2016 (UTC)

- Thanks and you deserve a prize for the speediest answer of the year! Looking back, I should perhaps have realised because the L. is not italicised; I had been thinking it was an abbreviation as part of the name, but obviously it would be italicised if it were. DrChrissy (talk) 20:30, 21 June 2016 (UTC)

- Like my namesake, I strike quickly, especially on matters of meaning ;) SemanticMantis (talk) 20:37, 21 June 2016 (UTC)

- Thanks and you deserve a prize for the speediest answer of the year! Looking back, I should perhaps have realised because the L. is not italicised; I had been thinking it was an abbreviation as part of the name, but obviously it would be italicised if it were. DrChrissy (talk) 20:30, 21 June 2016 (UTC)

References

- ^ Wilson, C.J. (2013). "The establishment and distribution of feral wild boar (Sus scrofa L.) in England". Wildlife Biology in Practice. 10 (3): 1–6.

- I believe your aquatic namesakes can strike so quickly they make light (see Sonoluminescence)! How awesome is that! DrChrissy (talk) 20:48, 21 June 2016 (UTC)

- And today I learned that there's a redirect from Linneaus. —Tamfang (talk) 08:32, 22 June 2016 (UTC)

- Haha yeah I realized my typo eventually but then decided to rock the redirect from misspelling :) SemanticMantis (talk) 13:38, 22 June 2016 (UTC)

- And today I learned that there's a redirect from Linneaus. —Tamfang (talk) 08:32, 22 June 2016 (UTC)

June 22

Refractometry, part 2

So how do they prepare a thin slice of a translucent/opaque mineral for refractometry? What special tools (if any) do they need for this? 67.164.54.236 (talk) 00:59, 22 June 2016 (UTC)

- Normally they would cut off a slice with a diamond cutting wheel, then flatten a surface on a faceting machine. It can be glued to a glass slide with canada balsam. Then sliced off again, and then ground down to the thinness required. Lapidary is the topic about shaping stones and minerals. However to measure refractive index, it can also be done by crushing into small fragments that might be transparent, and then putting them in different immersion liquids, such as diiodomethane or α-monochloronaphthaline. There is the Duc de Chaulnes method, oblique illumination method, and Becke line method and observation of relief. My reference is "An Introduction to the Methods of Optical Crystallography" by F Donald Bloss.Graeme Bartlett (talk) 01:26, 22 June 2016 (UTC)

MOSFET driving several LEDs simultaneously

I'm trying to use a MOSFET to turn on/off several LEDs simultaneously like so[15] (only two LEDs shown). Do I need a resistor in series with the drain of Q1? Or the source of Q1? Or would that be extraneous?

I will be driving the MOSFET with the 3.3v GPIO of a microcontroller. Do I need a small resistor in front of Q1's gate to protect it? Johnson&Johnson&Son (talk) 04:48, 22 June 2016 (UTC)

- The devices shown are two opto-couplers driven by a MOSFET. So long as the values for R3 and R1 are appropriate, the MOSFET will not be damaged, since its drain current will be limited by those resistors. So you do not need a resistor in series with the drain. A series resistor in the gate lead would be wise, since current will flow in the gate-source circuit when the drive voltage is made positive. This resistor will also act as a stopper for RF energy picked up from say, a nearby radio transmitter or internet router. It should be connected directly at the gate terminal and a suitable value might be 47K. On the other side of that resistor (the GPIO side), you should connect a resistor of say 4.7K to ground, so that if the triggering voltage becomes indeterminate due to disconnection of the GPIO terminal, the gate is pulled down to ground and the LEDs stay off instead of perhaps flickering. Akld guy (talk) 08:18, 22 June 2016 (UTC)

- See Your µCPU what is the low output voltage? Tie the gate of the MOSFET to GND using a resistor located next to the MOSFET. Keep the gate wire as short as possible. You are using opto-couplers? Make sure there's no solder flux or dirt under the coupler device. Clean before operate on hazardous voltage. --Hans Haase (有问题吗) 11:38, 22 June 2016 (UTC)

Intestinal gas exchange

Recently, while experiencing a bit of bloat, I was wondering: Do gases in the intestine enter the blood stream to any measurable degree? I would think that if nutrients and water can cross over, then at least some amount of gas would also find its way across. On the other hand, there can't be too much gas exchange otherwise gas buildup wouldn't tend to be much of a problem. If there is some gas exchange, does that cause any problems with blood chemistry and the like? Dragons flight (talk) 07:24, 22 June 2016 (UTC)

- Many of these gases dissolve freely into the bloodstream, but they also dissolve freely out of it, making it possible to test them on the breath, etc. [16][17]. The second source seems to suggest that swallowed nitrogen is more persistent than oxygen, which is absorbed; meanwhile carbon dioxide can enter. Only 1/3 of people have the secret mutant power to generate methane; the rest have to content themselves with farting hydrogen and CO2. But I feel like I don't really have the answer, because I'd want to see rates of production and diffusion to get a full picture - I'm assuming it's all a matter of kinetics. Wnt (talk) 12:08, 22 June 2016 (UTC)

Finasteride and fertility.

Does Finasteride decrease the sperm count and thereby making one impotent ? — Preceding unsigned comment added by 182.18.177.78 (talk) 08:02, 22 June 2016 (UTC)

- Physicians use Finasteride primarily to treat BPH, informally known as an enlarged prostate, and the FDA approved label reports cases of diminished libido or erectile dysfunction. Finasteride partially inhibits 5α-reductase with side effects that include reduced Epididymis (outlet tube from testicle) and decreased sperm motility. Suspected Male impotence connected with BPH treatment can have many causes which will not be diagnosed on this ref. desk and should be resolved in consultation with a urologist who may prescribe any of a number of medications with different side effects. For example, Dutasteride is an alternative 5α-reductase inhibitor to Finasteride, with a different risk profile. AllBestFaith (talk) 11:46, 22 June 2016 (UTC)

- Note that decreased sperm count doesn't directly lead to impotence - lots of guys are shooting blanks and never know it until they start wondering why no babies are coming out! Wnt (talk) 12:10, 22 June 2016 (UTC)

Seeing a rocket go up

If a Long March 7 rocket launches at sunset 19:30, 2016 06 25 around 126 degrees to the southeast, around 100 km away, will we see it go up from the top of a building in Haikou? Anna Frodesiak (talk) 10:36, 22 June 2016 (UTC)

The human eye should certainly be able to see that amount of light at that distance - experiments showed that the eye can actually see a candle flame at 30 miles! However - it will rather depend on the weather! http://www.livescience.com/33895-human-eye.html Wymspen (talk) 11:49, 22 June 2016 (UTC)

- And you'll see it when it's just less than 1km from the ground, fwiw, based on a quick scan of this table --Tagishsimon (talk) 11:59, 22 June 2016 (UTC)

- Thank you, Wymspen and Tagishsimon!

Anna Frodesiak (talk) 21:14, 22 June 2016 (UTC)

Anna Frodesiak (talk) 21:14, 22 June 2016 (UTC)

- Thank you, Wymspen and Tagishsimon!

Magnetic field influence in neutron

Does the applying of a magnetic field influence the average lifetime of a neutron by increasing or decreasing from the value of approximately 15 minutes in absence of field?--82.137.9.64 (talk) 12:23, 22 June 2016 (UTC)

- Possibly, but by only an infinitesimally small amount. Ruslik_Zero 14:22, 22 June 2016 (UTC)

Which tetrapod group could evolve into a new class?

I wonder whether exists a tetrapod group which can evolve in a reasonable amount of time (ten-twenty million years?) into a new class of organisms as different as are mammals or birds.--Carnby (talk) 13:57, 22 June 2016 (UTC)

- My WP:CRYSTAL is cloudy, cannot read. You may be interested in exaptation, mutation rate, rate of evolution, and Error_catastrophe. Also this [18] article on a rapidly evolving group of fish looks interesting. SemanticMantis (talk) 15:15, 22 June 2016 (UTC)

- Agree with the above, but see also species problem. The concept of species is fraught with exceptions and hard-cases and it's much more easily defined than "class" or "family". A new class could be created at any time by deciding to organize phylogeny slightly differently. Matt Deres (talk) 16:16, 22 June 2016 (UTC)

- Organizing phylogeny differently, a ready-made new class could be Chelonia, couldn't it?--Carnby (talk) 16:40, 22 June 2016 (UTC)

- You would want to look for the current classes which already show great diversity between different sub-groups. Possibly bony v cartilaginous fish, turtles/tortoises v snakes v lizards/crocodilians, penguins v flying birds? Wymspen (talk) 17:59, 22 June 2016 (UTC)

- That would be true if we were fine with arbitrary classification, but the goal is to support these things with scientific evidence. We do get new evidence and shuffle things around quite a bit, but not classes. If you're doing modern systematics (largely via Computational_phylogenetics), classes are actually often easier and less subjective to separate than species are. Families are pretty tough. Given the species problem and the three-domain system, taxonomy gets more anchored and stable at the top and bottom, and it's the middle-to low taxonomic ranks like family that are most arbitrary. Consider that bird taxonomy has shuffled things quite a bit in recent decades, but class Aves has remained unchanged for quite a while. According to Tetrapod#History_of_classification, no tetrapod classes have changed since the reptiles and amphibians were split in 1804. SemanticMantis (talk) 18:40, 22 June 2016 (UTC)

- My point was not about re-classifying existing species. If you are considering where evolution might lead to such a high variance that it was no longer possible to consider all the species involved to belong to the same class, the logical starting point seems to be those classes where a very high level of variance has evolved already. I didn't suggest such a process for an mammalian groups, because the class is more recent, and probably shows less variance than the older ones (though the cetaceans may well be on their way). Wymspen (talk) 20:02, 22 June 2016 (UTC)

- Yes, I took your point, it was fine. I was replying to Matt Deres' comments on creating new classes of extant species, per WP:INDENT style. SemanticMantis (talk) 20:21, 22 June 2016 (UTC)

- My point was not about re-classifying existing species. If you are considering where evolution might lead to such a high variance that it was no longer possible to consider all the species involved to belong to the same class, the logical starting point seems to be those classes where a very high level of variance has evolved already. I didn't suggest such a process for an mammalian groups, because the class is more recent, and probably shows less variance than the older ones (though the cetaceans may well be on their way). Wymspen (talk) 20:02, 22 June 2016 (UTC)

- That would be true if we were fine with arbitrary classification, but the goal is to support these things with scientific evidence. We do get new evidence and shuffle things around quite a bit, but not classes. If you're doing modern systematics (largely via Computational_phylogenetics), classes are actually often easier and less subjective to separate than species are. Families are pretty tough. Given the species problem and the three-domain system, taxonomy gets more anchored and stable at the top and bottom, and it's the middle-to low taxonomic ranks like family that are most arbitrary. Consider that bird taxonomy has shuffled things quite a bit in recent decades, but class Aves has remained unchanged for quite a while. According to Tetrapod#History_of_classification, no tetrapod classes have changed since the reptiles and amphibians were split in 1804. SemanticMantis (talk) 18:40, 22 June 2016 (UTC)

- The biggest problem with the question as such is that "class" is an artifact of our evolving understanding of evolution and cladistics. That being said, birds and mammals probably would not have become considered new classes, except for extinction events. Given the widespread prevalence and small size of songbirds, rodents, and microchiroptera, my guess is they would probably survive another K/T type event, and speciate quite rapidly.

- Bats and whales are diverse enough that were all other mammals to go extinct, there'd be little sense in keeping them closer than turtles an birds. And I agree with the above statement that if you want to go with existing tetrapods, separating off the turtles and crocodiles from the lepidosauria would make the most sense. This is all my POV, of course. μηδείς (talk) 00:44, 23 June 2016 (UTC)