Heinrich Heine

Heinrich Heine | |

|---|---|

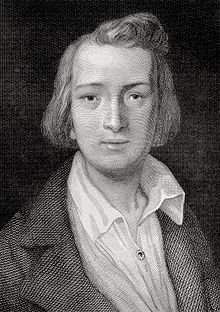

A painting of Heine by Moritz Daniel Oppenheim | |

| Born | Heinrich Heine 13 December 1797 Düsseldorf |

| Died | 17 February 1856 (aged 58) Paris, France |

| Occupation | Poet, essayist, journalist, literary critic |

| Nationality | German |

| Alma mater | Bonn, Berlin, Göttingen |

| Literary movement | Romanticism |

| Notable works | Buch der Lieder, Reisebilder, Germany. A Winter's Tale, Atta Troll, Romanzero |

| Relatives | Salomon Heine, Gustav Heine von Geldern, Karl Marx |

| Signature | |

Christian Johann Heinrich Heine (13 December 1797 – 17 February 1856) was a German poet, journalist, essayist, and literary critic. He is best known outside Germany for his early lyric poetry, which was set to music in the form of Lieder (art songs) by composers such as Robert Schumann and Franz Schubert. Heine's later verse and prose are distinguished by their satirical wit and irony. He is considered part of the Young Germany movement. His radical political views led to many of his works being banned by German authorities. Heine spent the last 25 years of his life as an expatriate in Paris.

Early life

Childhood and youth

Heine was born in Düsseldorf, Rhineland, to a Jewish family. He was called "Harry" in childhood but became known as "Heinrich" after his conversion to Christianity in 1825.[1] Heine's father, Samson Heine (1764–1828), was a textile merchant. His mother Peira (known as "Betty"), née van Geldern (1771–1859), was the daughter of a physician.

Heinrich was the eldest of four children. His siblings were Charlotte; Gustav Heine von Geldern, later Baron Heine-Geldern and publisher of the Viennese newspaper de:Das Fremden-Blatt; and Maximilian, who became a physician in Saint Petersburg.[2] Heine was also a third cousin once removed of philosopher and economist Karl Marx, also born to a German Jewish family in the Rhineland, with whom he became a frequent correspondent in later life.[3]

Düsseldorf was then a small town with a population of around 16,000. The French Revolution and subsequent Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars involving Germany complicated Düsseldorf's political history during Heine's childhood. It had been the capital of the Duchy of Jülich-Berg, but was under French occupation at the time of his birth.[4] It then went to the Elector of Bavaria before being ceded to Napoleon in 1806, who turned it into the capital of the Grand Duchy of Berg; one of three French states he established in Germany. It was first ruled by Joachim Murat, then by Napoleon himself.[5] Upon Napoleon's downfall in 1815 it became part of Prussia.

Thus Heine's formative years were spent under French influence. The adult Heine would always be devoted to the French for introduction of the Napoleonic Code and trial by jury. He glossed over the negative aspects of French rule in Berg: heavy taxation, conscription, and economic depression brought about by the Continental Blockade (which may have contributed to his father's bankruptcy).[6][7] Heine greatly admired Napoleon as the promoter of revolutionary ideals of liberty and equality and loathed the political atmosphere in Germany after Napoleon's defeat, marked by the conservative policies of Austrian chancellor Metternich, who attempted to reverse the effects of the French Revolution.[8]

Heine's parents were not particularly devout. As a young child they sent him to a Jewish school where he learned a smattering of Hebrew, but thereafter he attended Catholic schools. Here he learned French, which would be his second language - although he always spoke it with a German accent. He also acquired a lifelong love for Rhineland folklore.[9]

In 1814 Heine went to a business school in Düsseldorf where he learned to read English, the commercial language of the time.[10] The most successful member of the Heine family was his uncle Salomon Heine, a millionaire banker in Hamburg. In 1816 Heine moved to Hamburg to become an apprentice at Heckscher & Co, his uncle's bank, but displayed little aptitude for business. He learned to hate Hamburg with its commercial ethos, but it would become one of the poles of his life alongside Paris.

When he was 18, Heine almost certainly had an unrequited love for his cousin Amalie, Salomon's daughter. Whether he then transferred his affections (equally unsuccessfully) to her sister Therese is unknown.[11] This period in Heine's life is not clear but it seems that his father's business deteriorated, making Samson Heine effectively the ward of his brother Salomon.[12]

Universities

Salomon realised that his nephew had no talent for trade and it was decided that Heine should enter the law. So, in 1819, Heine went to the University of Bonn (then in Prussia). Political life in Germany was divided between conservatives and liberals. The conservatives, who were in power, wanted to restore things to the way they were before the French Revolution. They were against German unification because they felt a united Germany might fall victim to revolutionary ideas. Most German states were absolutist monarchies with a censored press. The opponents of the conservatives, the liberals, wanted to replace absolutism with representative, constitutional government, equality before the law and a free press. At the University of Bonn, liberal students were at war with the conservative authorities. Heine was a radical liberal and one of the first things he did after his arrival was to take part in a parade which violated the Carlsbad Decrees, a series of measures introduced by Metternich to suppress liberal political activity.[13]

Heine was more interested in studying history and literature than law. The university had engaged the famous literary critic and thinker August Wilhelm Schlegel as a lecturer and Heine heard him talk about the Nibelungenlied and Romanticism. Though he would later mock Schlegel, Heine found in him a sympathetic critic for his early verses. Heine began to acquire a reputation as a poet at Bonn. He also wrote two tragedies, Almansor and William Ratcliff, but they had little success in the theatre.[14]

After a year at Bonn, Heine left to continue his law studies at the University of Göttingen. Heine hated the town. It was part of Hanover, ruled by the King of England, the power Heine blamed for bringing Napoleon down. Here the poet experienced an aristocratic snobbery absent elsewhere. He also hated law as the Historical School of law he had to study was used to bolster the reactionary form of government he opposed. Other events conspired to make Heine loathe this period of his life: he was expelled from a student fraternity for anti-Semitic reasons and he heard the news that his cousin Amalie had become engaged. When Heine challenged another student, Wiebel, to a duel (the first of ten known incidents throughout his life), the authorities stepped in and Heine was suspended from the university for six months. His uncle now decided to send him to the University of Berlin.[15]

Heine arrived in Berlin in March 1821. It was the biggest, most cosmopolitan city he had ever visited (its population was about 200,000). The university gave Heine access to notable cultural figures as lecturers: the Sanskritist Franz Bopp and the Homer critic F. A. Wolf, who inspired Heine's lifelong love of Aristophanes. Most important was the philosopher Hegel, whose influence on Heine is hard to gauge. He probably gave Heine and other young students the idea that history had a meaning which could be seen as progressive.[16] Heine also made valuable acquaintances in Berlin, notably the liberal Karl August Varnhagen and his Jewish wife Rahel, who held a leading salon.

Another friend was the satirist Karl Immermann, who had praised Heine's first verse collection, Gedichte, when it appeared in December 1821.[17] During his time in Berlin Heine also joined the Verein für Cultur und Wissenschaft der Juden, a society which attempted to achieve a balance between the Jewish faith and modernity. Since Heine was not very religious in outlook he soon lost interest, but he also began to investigate Jewish history. He was particularly drawn to the Spanish Jews of the Middle Ages. In 1824 Heine began a historical novel, Der Rabbi von Bacherach, which he never managed to finish.[18]

In May 1823 Heine left Berlin for good and joined his family at their new home in Lüneburg. Here he began to write the poems of the cycle Die Heimkehr ("The Homecoming"). He returned to Göttingen where he was again bored by the law. In September 1824 he decided to take a break and set off on a trip through the Harz mountains. On his return he started writing an account of it, Die Harzreise.[19]

On 28 June 1825 Heine converted to Protestantism. The Prussian government had been gradually restoring discrimination against Jews. In 1822 it introduced a law excluding Jews from academic posts and Heine had ambitions for a university career. As Heine said in self-justification, his conversion was "the ticket of admission into European culture". In any event, Heine's conversion, which was reluctant, never brought him any benefits in his career.[20][21]

Julius Campe and first literary successes

Heine now had to search for a job. He was only really suited to writing but it was extremely difficult to be a professional writer in Germany. The market for literary works was small and it was only possible to make a living by writing virtually non-stop. Heine was incapable of doing this so he never had enough money to cover his expenses. Before finding work, Heine visited the North Sea resort of Norderney which inspired the free verse poems of his cycle Die Nordsee.[22]

In Hamburg one evening in January 1826 Heine met Julius Campe, who would be his chief publisher for the rest of his life. Their stormy relationship has been compared to a marriage. Campe was a liberal who published as many dissident authors as he could. He had developed various techniques for evading the authorities. The laws of the time stated that any book under 320 pages had to be submitted to censorship (the authorities thought long books would cause little trouble as they were unpopular). One way round censorship was to publish dissident works in large print to increase the number of pages beyond 320.

The censorship in Hamburg was relatively lax but Campe had to worry about Prussia, the largest German state which had the largest market for books (it was estimated that one-third of the German readership was Prussian). Initially, any book which had passed the censor in a German state was able to be sold in any of the other states but in 1834 this loophole was closed. Campe was reluctant to publish uncensored books as he had bad experience of print runs being confiscated. Heine resisted all censorship. So this issue became a bone of contention between the two.[23] But the relationship between author and publisher started well: Campe published the first volume of Reisebilder ("Travel Pictures") in May 1826. This volume included Die Harzreise, which marked a new style of German travel-writing, mixing Romantic descriptions of Nature with satire. Heine's Buch der Lieder followed in 1827. This was a collection of already published poems. No one expected it would be one of the most popular books of German verse ever published and sales were slow to start with, picking up when composers began setting Heine's poems as Lieder.[24] For example, the poem "Allnächtlich im Traume" of the Buch der Lieder was set to music by Robert Schumann as well as by Felix Mendelssohn. It contains the ironical disillusionment which is typical of Heine:

- Allnächtlich im Traume seh ich dich,

- Und sehe dich freundlich grüßen,

- Und lautaufweinend stürz ich mich

- Zu deinen süßen Füßen.

- Du siehst mich an wehmütiglich,

- Und schüttelst das blonde Köpfchen;

- Aus deinen Augen schleichen sich

- Die Perlentränentröpfchen.

- Du sagst mir heimlich ein leises Wort,

- Und gibst mir den Strauß von Zypressen.

- Ich wache auf, und der Strauß ist fort,

- Und das Wort hab ich vergessen.

(non-literal translation in verse by Hal Draper:)

- Nightly I see you in dreams-you speak,

- With kindliness sincerest,

- I throw myself, weeping aloud and weak

- At your sweet feet, my dearest.

- You look at me with wistful woe,

- And shake your golden curls;

- And stealing from your eyes there flow

- The teardrops like to pearls.

- You breathe in my ear a secret word,

- A garland of cypress for token.

- I wake; it is gone; the dream is blurred,

- And forgotten the word that was spoken.

Starting from the mid-1820s Heine distanced himself from Romanticism by adding irony, sarcasm and satire into his poetry and making fun of the sentimental-romantic awe of nature and of figures of speech in contemporary poetry and literature.[25] An example are these lines:

Das Fräulein stand am Meere

Und seufzte lang und bang.

Es rührte sie so sehre

der Sonnenuntergang.

Mein Fräulein! Sein sie munter,

Das ist ein altes Stück;

Hier vorne geht sie unter

Und kehrt von hinten zurück.

A mistress stood by the sea

sighing long and anxiously.

She was so deeply stirred

By the setting sun

My Fräulein!, be gay,

This is an old play;

ahead of you it sets

And from behind it returns.

Heine became increasingly critical of despotism and reactionary chauvinism in Germany, of nobility and clerics but also of the narrow-mindedness of ordinary people and of the rising German form of nationalism, especially in contrast to the French and the revolution. Nevertheless, he made a point of stressing his love for his Fatherland:

Plant the black, red, gold banner at the summit of the German idea, make it the standard of free mankind, and I will shed my dear heart's blood for it. Rest assured, I love the Fatherland just as much as you do.

Travel and the Platen affair

The first volume of travel writings was such a success that Campe pressed Heine for another. Reisebilder II appeared in April 1827. It contains the second cycle of North Sea poems, a prose essay on the North Sea as well as a new work, Ideen: Das Buch Le Grand, which contains the following satire on German censorship:[26]

The German Censors —— —— —— —— ——

—— —— —— —— —— —— —— —— —— ——

—— —— —— —— —— —— —— —— —— ——

—— —— —— —— —— —— —— —— —— ——

—— —— —— —— —— —— —— —— —— ——

—— —— —— —— —— —— —— —— —— ——

—— —— —— —— —— idiots —— ——

—— —— —— —— —— —— —— —— —— ——

—— —— —— —— —— —— —— —— —— ——

—— —— —— —— —— —— —— —— —— ——

—— —— —— —— ——

Heine went to England to avoid what he predicted would be controversy over the publication of this work. In London he cashed a cheque from his uncle for £200 (equal to £21,870 today), much to Salomon's chagrin. Heine was unimpressed by the English: he found them commercial and prosaic and still blamed them for the defeat of Napoleon.[28]

On his return to Germany, Cotta, the liberal publisher of Goethe and Schiller, offered Heine a job co-editing a magazine, Politische Annalen, in Munich. Heine did not find work on the newspaper congenial, and instead tried to obtain a professorship at Munich University, with no success.[29] After a few months he took a trip to northern Italy, visiting Lucca, Florence and Venice, but was forced to return when he received news that his father had died. This Italian journey resulted in a series of new works: Die Reise von München nach Genua ("Journey from Munich to Genoa"), Die Bäder von Lucca ("The Baths of Lucca") and Die Stadt Lucca ("The Town of Lucca").[30] Die Bäder von Lucca embroiled Heine in controversy. The aristocratic poet August von Platen had been annoyed by some epigrams by Immermann which Heine had included in the second volume of Reisebilder. He counter-attacked by writing a play, Der romantische Ödipus, which included anti-Semitic jibes about Heine. Heine was stung and responded by mocking Platen's homosexuality in Die Bäder von Lucca.[31]

Paris years

Foreign correspondent

In 1831 Heine left Germany for France, settling in Paris for his remaining 25 years of life. His move was prompted by the July Revolution of 1830 which had made Louis-Philippe the "Citizen King" of the French. Heine shared liberal enthusiasm for the revolution, which he felt had the potential to overturn the conservative political order in Europe.[32] Heine was also attracted by the prospect of freedom from German censorship and was interested in the new French utopian political doctrine of Saint-Simonianism. Saint-Simonianism preached a new social order in which meritocracy would replace hereditary distinctions in rank and wealth. There would also be female emancipation and an important role for artists and scientists. Heine frequented some Saint-Simonian meetings after his arrival in Paris but within a few years his enthusiasm for the ideology – and other forms of utopianism- had waned.[33][34]

Heine soon became a celebrity in France. Paris offered him a cultural richness unavailable in the smaller cities of Germany. He made many famous acquaintances (the closest were Gérard de Nerval and Hector Berlioz) but he always remained something of an outsider. He had little interest in French literature and wrote everything in German, subsequently translating it into French with the help of a collaborator.[35]

In Paris, Heine earned money working as the French correspondent for one of Cotta's newspapers, the Allgemeine Zeitung. The first event he covered was the Salon of 1831. His articles were eventually collected in a volume entitled Französische Zustände ("Conditions in France").[36] Heine saw himself as a mediator between Germany and France. If the two countries understood one another there would be progress. To further this aim he published De l'Allemagne ("On Germany") in French (begun 1833). In its later German version, the book is divided into two: Zur Geschichte der Religion und Philosophie in Deutschland ("On the History of Religion and Philosophy in Germany") and Die romantische Schule ("The Romantic School"). Heine was deliberately attacking Madame de Staël's book De l'Allemagne (1813) which he viewed as reactionary, Romantic and obscurantist. He felt de Staël had portrayed a Germany of "poets and thinkers", dreamy, religious, introverted and cut off from the revolutionary currents of the modern world. Heine thought that such an image suited the oppressive German authorities. He also had an Enlightenment view of the past, seeing it as mired in superstition and atrocities. "Religion and Philosophy in Germany" describes the replacement of traditional "spiritualist" religion by a pantheism that pays attention to human material needs. According to Heine, pantheism had been repressed by Christianity and had survived in German folklore. He predicted that German thought would prove a more explosive force than the French Revolution.[37]

Heine had had few serious love affairs, but in late 1834 he made the acquaintance of a 19-year-old Paris shopgirl, Crescence Eugénie Mirat, whom he nicknamed "Mathilde". Heine reluctantly began a relationship with her. She was illiterate, knew no German, and had no interest in cultural or intellectual matters. Nevertheless, she moved in with Heine in 1836 and lived with him for the rest of his life (they were married in 1841).[38]

Young Germany and Ludwig Börne

Heine and his fellow radical exile in Paris, Ludwig Börne, had become the role models for a younger generation of writers who were given the name "Young Germany". They included Karl Gutzkow, Heinrich Laube, Theodor Mundt and Ludolf Wienbarg. They were liberal, but not actively political. Nevertheless, they still fell foul of the authorities. In 1835 Gutzkow published a novel, Wally die Zweiflerin ("Wally the Sceptic"), which contained criticism of the institution of marriage and some mildly erotic passages. In November of that year, the German Diet consequently banned publication of works by the Young Germans in Germany and – on Metternich's insistence – Heine's name was added to their number. Heine, however, continued to comment on German politics and society from a distance. His publisher was able to find some ways of getting around the censors and he was still free, of course, to publish in France.[39][40]

Heine's relationship with his fellow dissident Ludwig Börne was troubled. Since Börne did not attack religion or traditional morality like Heine, the German authorities hounded him less although they still banned his books as soon as they appeared. Börne was the idol of German immigrant workers in Paris. He was also a republican, while Heine was not. Heine regarded Börne, with his admiration for Robespierre, as a puritanical neo-Jacobin and remained aloof from him in Paris, which upset Börne, who began to criticise him (mostly semi-privately). In February 1837, Börne died. When Heine heard that Gutzkow was writing a biography of Börne, he began work on his own, severely critical "memorial" of the man.

When the book was published in 1840 it was universally disliked by the radicals and served to alienate Heine from his public. Even his enemies admitted that Börne was a man of integrity so Heine's ad hominem attacks on him were viewed as being in poor taste. Heine had made personal attacks on Börne's closest friend Jeanette Wohl so Jeannette's husband challenged Heine to a duel. It was the last Heine ever fought – he received a flesh wound in the hip. Before fighting, he decided to safeguard Mathilde's future in the event of his death by marrying her.[41]

Heine continued to write reports for Cotta's Allgemeine Zeitung (and, when Cotta died, for his son and successor). One event which really galvanised him was the 1840 Damascus Affair in which Jews in Damascus had been subject to blood libel and accused of murdering an old Catholic monk. This led to a wave of anti-Semitic persecution. The French government, aiming at imperialism in the Middle East and not wanting to offend the Catholic party, had failed to condemn the outrage. On the other hand, the Austrian consul in Damascus had assiduously exposed the blood libel as a fraud. For Heine, this was a reversal of values: reactionary Austria standing up for the Jews while revolutionary France temporised. Heine responded by dusting off and publishing his unfinished novel about the persecution of Jews in the Middle Ages, Der Rabbi von Bacherach.[42]

Political poetry and Karl Marx

In 1840 German poetry took a more directly political turn when the new Frederick William IV ascended the Prussian throne. Initially it was thought he might be a "popular monarch" and during this honeymoon period of his early reign (1840–42) censorship was relaxed. This led to the emergence of popular political poets (so-called Tendenzdichter), including Hoffmann von Fallersleben (the author of "Deutschland Über Alles"), Ferdinand Freiligrath and Georg Herwegh. Heine looked down on these writers on aesthetic grounds – they were bad poets in his opinion – but his verse of the 1840s became more political too.

Heine's mode was satirical attack: against the Kings of Bavaria and Prussia (he never for one moment shared the belief that Frederick William IV might be more liberal); against the political torpor of the German people; and against the greed and cruelty of the ruling class. The most popular of Heine's political poems was his least typical, Die schlesischen Weber ("The Silesian Weavers"), based on the uprising of weavers in Peterswaldau in 1844.[43][44]

In October 1843, Heine's distant relative and German revolutionary, Karl Marx, and his wife Jenny von Westphalen arrived in Paris after the Prussian government had suppressed Marx's radical newspaper. The Marx family settled in Rue Vaneau. Marx was an admirer of Heine and his early writings show Heine's influence. In December Heine met the Marxes and got on well with them. He published several poems, including Die schlesischen Weber, in Marx's new journal Vorwärts ("Forwards"). Ultimately Heine's ideas of revolution through sensual emancipation and Marx's scientific socialism were incompatible, but both writers shared the same negativity and lack of faith in the bourgeoisie.

In the isolation he felt after the Börne debacle, Marx's friendship came as a relief to Heine, since he did not really like the other radicals. On the other hand, he did not share Marx's faith in the industrial proletariat and remained on the fringes of socialist circles. The Prussian government, angry at the publication of Vorwärts, put pressure on France to deal with its authors and in January 1845 Marx was deported to Belgium. Heine could not be expelled from the country because he had the right of residence in France, having been born under French occupation.[45] Thereafter Heine and Marx maintained a sporadic correspondence, but in time their admiration for one another faded.[46][47] Heine always had mixed feelings about communism. He believed its radicalism and materialism would destroy much of the European culture that he loved and admired.

In the French edition of "Lutetia" Heine wrote, one year before he died: "This confession, that the future belongs to the Communists, I made with an undertone of the greatest fear and sorrow and, oh!, this undertone by no means is a mask! Indeed, with fear and terror I imagine the time, when those dark iconoclasts come to power: with their raw fists they will batter all marble images of my beloved world of art, they will ruin all those fantastic anecdotes that the poets loved so much, they will chop down my Laurel forests and plant potatoes and, oh!, the herbs chandler will use my Book of Songs to make bags for coffee and snuff for the old women of the future – oh!, I can foresee all this and I feel deeply sorry thinking of this decline threatening my poetry and the old world order – And yet, I freely confess, the same thoughts have a magical appeal upon my soul which I cannot resist .... In my chest there are two voices in their favour which cannot be silenced .... because the first one is that of logic ... and as I cannot object to the premise "that all people have the right to eat", I must defer to all the conclusions....The second of the two compelling voices, of which I am talking, is even more powerful than the first, because it is the voice of hatred, the hatred I dedicate to this common enemy that constitutes the most distinctive contrast to communism and that will oppose the angry giant already at the first instance – I am talking about the party of the so-called advocates of nationality in Germany, about those false patriots whose love for the fatherland only exists in the shape of imbecile distaste of foreign countries and neighbouring peoples and who daily pour their bile especially on France".[48]

In October–December 1843 Heine made a journey to Hamburg to see his aged mother and to patch things up with Campe with whom he had had a quarrel. He was reconciled with the publisher who agreed to provide Mathilde with an annuity for the rest of her life after Heine's death. Heine repeated the trip with his wife in July–October 1844 to see Uncle Salomon, but this time things did not go so well. It was the last time Heine would ever leave France.[49] At the time, Heine was working on two linked but antithetical poems with Shakespearean titles: Deutschland: Ein Wintermärchen ("Germany: A Winter's Tale") and Atta Troll: Ein Sommernachtstraum ("Atta Troll: A Midsummer Night's Dream"). The former is based on his journey to Germany in late 1843 and outdoes the radical poets in its satirical attacks on the political situation in the country.[50] Atta Troll (actually begun in 1841 after a trip to the Pyrenees) mocks the literary failings Heine saw in the radical poets, particularly Freiligrath. It tells the story of the hunt for a runaway bear, Atta Troll, who symbolises many of the attitudes Heine despised, including a simple-minded egalitarianism and a religious view which makes God in the believer's image (Atta Troll conceives God as an enormous, heavenly polar bear). Atta Troll's cubs embody the nationalistic views Heine loathed.[51]

Atta Troll was not published until 1847, but Deutschland appeared in 1844 as part of a collection Neue Gedichte ("New Poems"), which gathered all the verse Heine had written since 1831.[52] In the same year Uncle Salomon died. This put a stop to Heine's annual subsidy of 4,800 francs. Salomon left Heine and his brothers 8,000 francs each in his will. Heine's cousin Carl, the inheritor of Salomon's business, offered to pay him 2,000 francs a year at his discretion. Heine was furious; he had expected much more from the will and his campaign to make Carl revise its terms occupied him for the next two years.[53]

In 1844, Heine wrote series of musical feuilletons over several different music seasons discussing the music of the day. His review of the musical season of 1844, written in Paris on April 25, 1844, is his first reference to Lisztomania, the intense fan frenzy directed toward Franz Liszt during his performances. However, Heine was not always honorable in his musical criticism. In April 1844 he wrote to Liszt suggesting that he might like to look at a newspaper review he had written of Liszt's performance before his concert; he indicated that it contained comments Liszt would not like. Liszt took this as an attempt to extort money for a positive review and did not meet Heine. Heine's review subsequently appeared on April 25 in Musikalische Berichte aus Paris and attributed Liszt's success to lavish expenditures on bouquets and to the wild behaviour of his hysterical female "fans." Liszt then broke relations with Heine. Liszt was not the only musician to be blackmailed by Heine for the nonpayment of "appreciation money." Meyerbeer had both lent and given money to Heine, but after refusing to hand over a further 500 francs was repaid by being dubbed "a music corrupter" in Heine's poem Die Menge tut es.[54]

Last years: the "mattress-grave"

In May 1848, Heine, who had not been well, suddenly fell paralyzed and had to be confined to bed. He would not leave what he called his "mattress-grave" (Matratzengruft) until his death eight years later. He also experienced difficulties with his eyes.[55] It had been suggested that he suffered from multiple sclerosis or syphilis, although in 1997 it was confirmed through an analysis of the poet's hair that he had suffered from chronic lead poisoning.[56] He bore his sufferings stoically and he won much public sympathy for his plight.[57] His illness meant he paid less attention than he might otherwise have done to the revolutions which broke out in France and Germany in 1848. He was sceptical about the Frankfurt Assembly and continued to attack the King of Prussia. When the revolution collapsed, Heine resumed his oppositional stance. At first he had some hope Louis Napoleon might be a good leader in France but he soon began to share the opinion of Marx towards him as the new emperor began to crack down on liberalism and socialism.[58] In 1848 Heine also returned to religious faith. In fact, he had never claimed to be an atheist. Nevertheless, he remained sceptical of organised religion.[59]

He continued to work from his sickbed: on the collections of poems Romanzero and Gedichte (1853 und 1854), on the journalism collected in Lutezia, and on his unfinished memoirs.[60] During these final years Heine had a love affair with the young Camille Selden, who visited him regularly.[61] He died on 17 February 1856 and was interred in the Paris Cimetière de Montmartre. His wife Mathilde survived him, dying in 1883. The couple had no children.[62]

Legacy

| "The highest conception of the lyric poet was given to me by Heinrich Heine. I seek in vain in all the realms of millennia for an equally sweet and passionate music. He possessed that divine malice without which I cannot imagine perfection... And how he employs German! It will one day be said that Heine and I have been by far the first artists of the German language." — Friedrich Nietzsche, Ecce Homo[63] |

Among the thousands of books burned on Berlin's Opernplatz in 1933, following the Nazi raid on the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft, were works by Heinrich Heine. To commemorate the terrible event, one of the most famous lines of Heine's 1821 play Almansor was engraved in the ground at the site: "Das war ein Vorspiel nur, dort wo man Bücher verbrennt, verbrennt man auch am Ende Menschen." ("That was but a prelude; where they burn books, they will ultimately burn people as well.")

In 1834, 99 years before Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party seized power in Germany, Heine wrote in his work "The History of Religion and Philosophy in Germany":

- "Christianity – and that is its greatest merit – has somewhat mitigated that brutal Germanic love of war, but it could not destroy it. Should that subduing talisman, the cross, be shattered, the frenzied madness of the ancient warriors, that insane Berserk rage of which Nordic bards have spoken and sung so often, will once more burst into flame. This talisman is fragile, and the day will come when it will collapse miserably. Then the ancient stony gods will rise from the forgotten debris and rub the dust of a thousand years from their eyes, and finally Thor with his giant hammer will jump up and smash the Gothic cathedrals. (...)

"Do not smile at my advice – the advice of a dreamer who warns you against Kantians, Fichteans, and philosophers of nature. Do not smile at the visionary who anticipates the same revolution in the realm of the visible as has taken place in the spiritual. Thought precedes action as lightning precedes thunder. German thunder is of true Germanic character; it is not very nimble, but rumbles along ponderously. Yet, it will come and when you hear a crashing such as never before has been heard in the world's history, then you know that the German thunderbolt has fallen at last. At that uproar the eagles of the air will drop dead, and lions in the remotest deserts of Africa will hide in their royal dens. A play will be performed in Germany which will make the French Revolution look like an innocent idyll."

Heine also wrote in his 1820-1821 play Almansor the famous admonition, "Dort, wo man Bücher verbrennt, verbrennt man am Ende auch Menschen": "Where they burn books, they will also ultimately burn people." - a powerful prophesy of the Nazi book burning.

Nazi interpretations of Heine

Heine's writings were abhorred by the Nazis and one of its political mouthpieces, the Völkischer Beobachter, made noteworthy efforts to attack him in their periodical. Within the pantheon of the "Jewish cultural intelligentsia" chosen for "anti-Semitic demonization," perhaps nobody was the recipient of more National Socialist vitriol than Heinrich Heine.[64] When a memorial to Heine was completed in 1926, the paper lamented that Hamburg had erected a "Jewish Monument to Heine and Damascus...one in which Alljuda ruled!".[65] Editors for the Völkischer Beobachter referred to Heine's writing as degenerate on multiple occasions as did Alfred Rosenberg.[66] Correspondingly, during the rise of the Third Reich, Heine's writings were banned and burned.[67][68]

Music

Many composers have set Heine's works to music. They include Robert Schumann (especially his Lieder cycle Dichterliebe), Friedrich Silcher (who wrote a popular setting of "Die Lorelei", one of Heine's best known poems), Franz Schubert, Felix Mendelssohn, Fanny Mendelssohn, Johannes Brahms, Hugo Wolf, Richard Strauss, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Edward MacDowell, Clara Schumann and Richard Wagner; and in the 20th century Nikolai Medtner, Hans Werner Henze, Carl Orff, Lord Berners, Paul Lincke, Yehezkel Braun, Marcel Tyberg[69] and Friedrich Baumfelder (who wrote another setting of "Die Lorelei", as well as "Die blauen Frühlingsaugen" and "Wir wuchsen in demselben Thal" in his Zwei Lieder).

Heine's play William Ratcliff was used for the libretti of operas by César Cui (William Ratcliff) and Pietro Mascagni (Guglielmo Ratcliff). Frank van der Stucken composed a "symphonic prologue" to the same play.

Morton Feldman's I Met Heine on the Rue Fürstemberg was inspired by a vision he had of the dead Heine as he walked through Heine's old neighborhood in Paris: "One early morning in Paris I was walking along the small street on the Left Bank where Delacroix's studio is, just as it was more than a century ago. I'd read his journals, where he tells of Chopin, going for a drive, the poet Heine dropping in, a refugee from Germany. Nothing had changed in the street. And I saw Heine up at the corner, walking toward me. He almost reached me. I had this intense feeling for him, you know, the Jewish exile. I saw him. Then I went back to my place and wrote my work, I Met Heine on the Rue Fürstemberg."[70]

Controversy

In the 1890s, amidst a flowering of affection for Heine leading up to the centennial of his birth, plans were enacted to honor Heine with a memorial; these were strongly supported by one of Heine's greatest admirers, Elisabeth of Bavaria, Empress of Austria. The empress commissioned a statue from the sculptor Louis Hasselriis. Another memorial, a sculpted fountain, was commissioned for Düsseldorf. While at first the plan met with enthusiasm, the concept was gradually bogged down in anti-Semitic, nationalist, and religious criticism; by the time the fountain was finished, there was no place to put it. Through the intervention of German American activists, the memorial was ultimately transplanted into the Bronx, New York City. While it is known in English as the Lorelei Fountain, Germans refer to it as the Heinrich Heine Memorial.[71] Also, after years of controversy,[72] the University of Düsseldorf was named Heinrich Heine University. Today the city honours its poet with a boulevard (Heinrich-Heine-Allee) and a modern monument. A Heine statue, originally located near Empress Elisabeth's palace in Corfu, was later rejected by Hamburg, but eventually found a home in Toulon.[73]

In Israel, the attitude to Heine has long been the subject of debate between secularists, who number him among the most prominent figures of Jewish history, and the religious who consider his conversion to Christianity to be an unforgivable act of betrayal. Due to such debates, the city of Tel-Aviv delayed naming a street for Heine, and the street finally chosen to bear his name is located in a rather desolate industrial zone rather than in the vicinity of Tel-Aviv University, suggested by some public figures as the appropriate location.

Ha'ir (a left-leaning Tel-Aviv magazine) sarcastically suggested that "The Exiling of Heine Street" symbolically re-enacted the course of Heine's own life. Since then, a street in the Yemin Moshe neighborhood of Jerusalem[74] and, in Haifa, a street with a beautiful square and a community center have been named after Heine. A Heine Appreciation Society is active in Israel, led by prominent political figures from both the left and right camps. His quote about burning books is prominently displayed in the Yad Vashem Holocaust museum in Jerusalem. (It is also displayed in the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum).

-

Heine monument in Düsseldorf

-

Heine monument in Frankfurt, the only pre-1945 one in Germany

-

Heine monument in Berlin

-

Grave in Montmartre Paris

-

Grave and poem "Wo ?"

-

1956 German stamp commemorating the 100th anniversary of Heine's death (Federal Republic of Germany)

-

1956 Soviet stamp commemorating the 100th anniversary of Heine's death

Works

A list of Heine's major publications in German. All dates are taken from Jeffrey L. Sammons: Heinrich Heine: A Modern Biography (Princeton University Press, 1979).

- 1820 (August): Die Romantik ("Romanticism", short critical essay)

- 1821 (20 December [75]): Gedichte ("Poems")

- 1822 (February to July): Briefe aus Berlin ("Letters from Berlin")

- 1823 (January): Über Polen ("On Poland", prose essay)

- 1823 (April): Tragödien nebst einem lyrischen Intermezzo ("Tragedies with a Lyrical Intermezzo") includes:

- Almansor (play, written 1821–1822)

- William Ratcliff (play, written January 1822)

- Lyrisches Intermezzo (cycle of poems)

- 1826 (May): Reisebilder. Erster Teil ("Travel Pictures I"), contains:

- Die Harzreise ("The Harz Journey", prose travel work)

- Die Heimkehr ("The Homecoming", poems)

- Die Nordsee. Erste Abteilung ("North Sea I", cycle of poems)

- 1827 (April): Reisebilder. Zweiter Teil ("Travel Pictures II"), contains:

- Die Nordsee. Zweite Abteilung ("The North Sea II", cycle of poems)

- Die Nordsee. Dritte Abteilung ("The North Sea III", prose essay)

- Ideen: das Buch le Grand ("Ideas: The Book of Le Grand")

- Briefe aus Berlin ("Letters from Berlin", a much shortened and revised version of the 1822 work)

- 1827 (October): Buch der Lieder ("Book of Songs"); collection of poems containing the following sections:

- Junge Leiden ("Youthful Sorrows")

- Die Heimkehr ("The Homecoming", originally published 1826)

- Lyrisches Intermezzo" ("Lyrical Intermezzo", originally published 1823)

- "Aus der Harzreise" (poems from Die Harzreise, originally published 1826)

- Die Nordsee ("The North Sea: Cycles I and II", originally published 1826/1827)

- 1829 (December): Reisebilder. Dritter Teil ("Travel Pictures III"), contains:

- Die Reise von München nach Genua ("Journey from Munich to Genoa", prose travel work)

- Die Bäder von Lucca ("The Baths of Lucca", prose travel work)

- Anno 1829

- 1831 (January): Nachträge zu den Reisebildern ("Supplements to the Travel Pictures"), the second edition of 1833 was retitled as Reisebilder. Vierter Teil ("Travel Pictures IV"), contains:

- Die Stadt Lucca ("The Town of Lucca", prose travel work)

- Englische Fragmente ("English Fragments", travel writings)

- 1831 (April): Zu "Kahldorf über den Adel" (introduction to the book "Kahldorf on the Nobility", uncensored version not published until 1890)

- 1833: Französische Zustände ("Conditions in France", collected journalism)

- 1833 (December): Der Salon. Erster Teil ("The Salon I"), contains:

- Französische Maler ("French Painters", criticism)

- Aus den Memoiren des Herren von Schnabelewopski ("From the Memoirs of Herr Schnabelewopski", unfinished novel)

- 1835 (January): Der Salon. Zweiter Teil ("The Salon II"), contains:

- Zur Geschichte der Religion und Philosophie in Deutschland ("On the History of Religion and Philosophy in Germany")

- Neuer Frühling ("New Spring", cycle of poems)

- 1835 (November): Die romantische Schule ("The Romantic School", criticism)

- 1837 (July): Der Salon. Dritter Teil ("The Salon III"), contains:

- Florentinische Nächte ("Florentine Nights", unfinished novel)

- Elementargeister ("Elemental Spirits", essay on folklore)

- 1837 (July): Über den Denunzianten. Eine Vorrede zum dritten Teil des Salons. ("On the Denouncer. A Preface to Salon III", pamphlet)

- 1837 (November): Einleitung zum "Don Quixote" ("Introduction to Don Quixote", preface to a new German translation of Don Quixote)

- 1838 (November): Der Schwabenspiegel ("The Mirror of Swabia", prose work attacking poets of the Swabian School)

- 1838 (October): Shakespeares Mädchen und Frauen ("Shakespeare's Girls and Women", essays on the female characters Shakespeare's tragedies and histories)

- 1839: Anno 1839

- 1840 (August): Ludwig Börne. Eine Denkschrift ("Ludwig Börne: A Memorial", long prose work about the writer Ludwig Börne)

- 1840 (November): Der Salon. Vierter Teil ("The Salon IV"), contains:

- Der Rabbi von Bacherach ("The Rabbi of Bacharach", unfinished historical novel)

- Über die französische Bühne ("On the French Stage", prose criticism)

- 1844 (September): Neue Gedichte ("New Poems"); contains the following sections:

- Neuer Frühling ("New Spring", originally published in 1834)

- Verschiedene ("Sundry Women")

- Romanzen ("Ballads")

- Zur Ollea ("Olio")

- Zeitgedichte ("Poems for the Times")

- it also includes Deutschland: Ein Wintermärchen ("Germany: A Winter's Tale", long poem)

- 1847 (January): Atta Troll: Ein Sommernachtstraum ("Atta Troll: A Midsummer Night's Dream", long poem, written 1841–46)

- 1851 (September): Romanzero; collection of poems divided into three books:

- Erstes Buch: Historien ("First Book: Histories")

- Zweites Buch: Lamentationen ("Second Book: Lamentations")

- Drittes Buch: Hebräische Melodien ("Third Book: Hebrew Melodies")

- 1851 (October): Der Doktor Faust. Tanzpoem ("Doctor Faust. Dance Poem", ballet libretto, written 1846)

- 1854 (October): Vermischte Schriften ("Miscellaneous Writings") in three volumes, contains:

- Volume One:

- Geständnisse ("Confessions", autobiographical work)

- Die Götter im Exil ("The Gods in Exile", prose essay)

- Die Göttin Diana ("The Goddess Diana", ballet scenario, written 1846)

- Ludwig Marcus: Denkworte ("Ludwig Marcus: Recollections", prose essay)

- Gedichte. 1853 und 1854 ("Poems. 1854 and 1854")

- Volume Two:

- Lutezia. Erster Teil ("Lutetia I", collected journalism about France)

- Volume Three:

- Lutezia. Zweiter Teil ("Lutetia II", collected journalism about France)

- Volume One:

Posthumous publications

- Memoiren ("Memoirs", first published in 1884 in the magazine Die Gartenlaube)

Editions in English

- Poems of Heinrich Heine, Three hundred and Twenty-five Poems, Translated by Louis Untermeyer, Henry Holt, New York, 1917.

- The Complete Poems of Heinrich Heine: A Modern English Version by Hal Draper, Suhrkamp/Insel Publishers Boston, 1982. ISBN 3-518-03048-5

See also

- Die Lotosblume

- On Wings of Song (poem and song)

- Heinrich Heine University of Düsseldorf

- Heinrich Heine Prize

- The Gaze of the Gorgon

References

- ^ "There was an old rumor, propagated particularly by anti-Semites, that Heine's Jewish name was Chaim, but there is no evidence for it". Ludwig Börne: A Memorial, ed. Jeffrey L. Sammons, Camden House, 2006, p. 13 n. 42.

- ^ Sammons Heinrich Heine: A Modern Biography, pages 11 to 30

- ^ Raddatz Karl Marx: A Political Biography

- ^ Sammons p.30

- ^ In the name of his four-year-old nephew, Napoleon Louis. (Sammons, page 31)

- ^ Sammons p.32

- ^ Sammons in Heinrich Heine: Alternative Perspectives 1985–2005 , p. 67

- ^ Sammons, pages 30 to 35

- ^ Sammons, pages 35 to 42

- ^ Sammons, page 47

- ^ Sammons, pages 42 to 46

- ^ Sammons, pages 47 to 51

- ^ Robertson Heine, pages 14 to 15

- ^ Sammons, pages 55 to 70

- ^ Sammons, pages 70 to 74

- ^ Sammons, pages 74 to 81

- ^ Sammons, pages 81 to 85

- ^ Sammons, pages 89 to 96

- ^ Sammons, pages 96 to 107

- ^ Sammons, pages 107 to 110

- ^ Robertson Heine pages 84 to 85

- ^ Sammons, pages 113 to 118

- ^ Sammons, pages 118 to 124

- ^ Sammons, pages 124 to 126

- ^ Neue Gedichte (New Poems), citing: DHA, Vol. 2, p. 15

- ^ Sammons, pages 127 to 129

- ^ Heine, Ideen. Das Buch Le Grand, Chapter 12

- ^ Sammons, pages 129 to 132

- ^ Sammons, pages 132 to 138

- ^ Sammons, pages 138 to 141

- ^ Sammons, pages 141 to 147

- ^ Sammons, pages 150 to 155

- ^ See Sammons, pages 159 to 168

- ^ Robertson, Heine, pages 36 to 38

- ^ Sammons, pages 168 to 171

- ^ Sammons, pages 172 to 183

- ^ Sammons, pages 188 to 197

- ^ Sammons, pages 197 to 205

- ^ Sammons, pages 205 to 218

- ^ Robertson Heine p.20

- ^ Sammons, pages 233 to 242

- ^ Sammons, pages 243 to 244

- ^ Sammons, pages 253 to 260

- ^ Robertson Heine pp.22 to 23

- ^ Sammons, page 285

- ^ Sammons, pages 260 to 265

- ^ Robertson Heine pages 68 to 70

- ^ Heine's draft for Préface in the French edition of Lutezia (1855), DHA, Vol. 13/1, p. 294.

- ^ Sammons, pages 265 to 268

- ^ Sammons, pages 268 to 275

- ^ Robertson Heine pages 24 to 26

- ^ Sammons, pages 275 to 278

- ^ Sammons, pages 278 to 285

- ^ Walker, Alan, Franz Liszt: The virtuoso years, 1811–1847, Cornell University Press; Rev. ed edition, 1997, p. 164

- ^ Sammons, pages 295 to 297

- ^ Bundesgesundheitsbl – Gesundheitsforsch – Gesundheitsschutz 2005, 48 (2):246–250 (in German)

- ^ Sammons, page 297

- ^ Sammons, pages 298 to 302

- ^ Sammons, pages 305 to 310

- ^ See Sammons, pages 310 to 338

- ^ Sammons, pages 341 to 343

- ^ Sammons, pages 343 to 344

- ^ Friedrich Nietzsche, A Nietzsche Reader, Translated by R.J. Hollingdale, Penguin 1977, page 147

- ^ David B. Dennis, Inhumanities: Nazi Interpretations of Western Culture (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012), pp. 110-123.

- ^ "Ein Heinrich Heine-Denkmal in Hamburg," Völkischer Beobachter, October, 1926; as found in Heinrich Heine im Dritten Reich und im Exil by Hartmut Steinecke (Paderborn: Schöningh, 2008), p. 10-12.

- ^ Alfred Rosenberg, The Myth of the 20th Century (Mythus des XX. Jahrhunderts): An Evaluation of the Spiritual-Intellectual Confrontations of Our Age. https://archive.org/stream/TheMythOfTheTwentiethCentury_400/MythOfThe20thCentury_djvu.txt

- ^ Rupert Colley (2010). Nazi Germany In An Hour. History In An Hour. p. 19-20

- ^ Jonathan Skolnik, Jewish Pasts, German Fictions: History, Memory, and Minority Culture in Germany, 1824-1955 (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2014), p. 147

- ^ Buffalo News. Performers revel in premiere of Tyberg songs

- ^ Feldman, Morton (2000). Friedman, B.H. (ed.). Give My Regards to Eighth Street. Cambridge: Exact Change. pp. 120–121. ISBN 1-878972-31-6.

- ^ Sturm und Drang Over a Memorial to Heinrich Heine. The New York Times, 27 May 2007.

- ^ WEST GERMAN UNIVERSITIES: WHAT TO CALL THEM? by John Vinocur, The New York Times, March 31, 1982

- ^ Richard S. Levy, Heine Monument Controversy, in Antisemitism: A Historical Encyclopedia of Prejudice and Persecution, ABC-CLIO, 2005, p.295

- ^ Jewish Postcards from... haGalil onLine.

- ^ The title page says "1822"

Sources

- Dennis, David B. Inhumanities: Nazi Interpretations of Western Culture. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

- Robertson, Ritchie. Heine (Jewish Thinkers Series). London: Halban, 1988.

- Sammons, Jeffrey L. Heinrich Heine: A Modern Biography. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1979.

- Skolnik, Jonathan. Jewish Pasts, German Fictions: History, Memory, and Minority Culture in Germany, 1824-1955. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2014.

External links

- Works by Heinrich Heine at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Heinrich Heine at the Internet Archive

- Works by Heinrich Heine at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- The German classics of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries: masterpieces of German literature translated into English" 1913–1914 "Heinrich Heine,". Retrieved 2010-09-24.

- Parallel German/English text of Heine's poem Geoffroy Rudel and Melisande of Tripoli

- Deutsche Welle's review of Heinrich Heine in 2006, 150 years after his death

- "Ihr Lieder! Ihr meine guten Lieder!" a performer's guide, and "Heine Lieder Query" a searchable database with over 8000 entries, both covering musical settings of Heine's poetry for one or two voices, by Peter W. Shea

- Art of the States: The Resounding Lyre – musical setting of Heine's poem "Halleluja"

- Heinrich Heine's holy hits – Georg Klein's top ten Heine quotes on religion

- Free scores of texts by Heinrich Heine in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

- Loving Herodias by David P. Goldman, First Things

- Heinrich Heine(German author)-Britannica Online Encyclopedia

- Heinrich Heine

- 1797 births

- 1856 deaths

- People from Düsseldorf

- 19th-century German people

- German poets

- German-language poets

- Romantic poets

- German Protestants

- German travel writers

- Writers from North Rhine-Westphalia

- Saint-Simonists

- German socialists

- University of Bonn alumni

- University of Göttingen alumni

- Jewish German history

- Converts to Protestantism from Judaism

- Jewish poets

- German Jews

- German expatriates in France

- Burials at Montmartre Cemetery