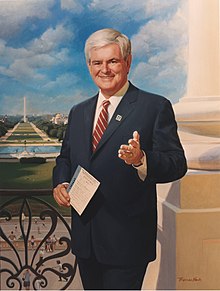

Newt Gingrich

The neutrality of this article is disputed. |

Newt Gingrich | |

|---|---|

| |

| 58th Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives | |

| In office January 4 1995 – January 3 1999 | |

| Preceded by | Tom Foley |

| Succeeded by | Dennis Hastert |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Georgia's 6th district | |

| In office 1979 - 1999 | |

| Preceded by | Jack Flynt |

| Succeeded by | Johnny Isakson |

| Personal details | |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse | Callista Gingrich |

Newton Leroy Gingrich (born June 17, 1943) is an American politician who is best known as the Speaker of the United States House of Representatives from 1995 to 1999. In 1995 he was named Time Magazine's Man of the Year for his role in leading the Republican Revolution in Congress, ending 40 years of Democratic majorities in the House. During his tenure as Speaker he represented the public face of the Republican opposition to President Bill Clinton.

A college history professor and prolific author, Gingrich twice ran unsuccessfully for the House before first winning a seat in November 1978. He was re-elected ten times, and his activism as a member of the House's Republican minority eventually enabled him to succeed Dick Cheney as House Minority Whip in 1989. As a co-author of the 1994 Contract with America, Gingrich was in the forefront of the Republican Party's dramatic success in the 1994 Congressional elections, and was subsequently elected Speaker. Gingrich's leadership in Congress was marked by opposition to many of the policies of the Clinton Administration and Gingrich presided over the House during the impeachment of President Clinton.

After resigning his seat under pressure from several sides, Gingrich has maintained a career as a political analyst and consultant, and continues to write works related to government and other subjects such as historical fiction. He has expressed interest in being a candidate for the 2008 Republican nomination for the Presidency.[1]

Gingrich has been married three times. He married his first wife, Jackie Battley, in 1962, and divorced her in 1981. Gingrich married his second wife, Marianne Ginther, in the fall of 1981.[2] They divorced in 1999, after revealing that he had been having an affair with a House aide, Callista Bisek.[3] Gingrich and Bisek were married the following year.

Early life and education

He was born Newton McPherson in Dauphin, Pennsylvania, the son of Newton Searles McPherson and Kathleen Daugherty. His parents separated soon after Newt's birth, and his mother raised him by herself until she married Robert Gingrich, who adopted Newt. Gingrich has a younger half-sister, Candace Gingrich, who was born when he was already a young adult. Gingrich rarely saw her when she was growing up.

Gingrich's adopted surname has been generally pronounced "Ging-ritch" since his entry into public life. However, his adoptive family has always pronounced the name "Gin-grick," as would be customary in the Pennsylvania Dutch ethnic milieu.

Gingrich attended school at various military installations and graduated from Baker High School, Columbus, Georgia, in 1961. He received a B.A. degree from Emory University in Atlanta in 1965. He received an M.A. in 1968 and Ph.D. in 1971 in Modern European History from Tulane University in New Orleans. He taught history at West Georgia College in Carrollton, Georgia, from 1970 to 1978, although he was denied tenure.[4]

In 1962, Gingrich married his first wife, Jackie Battley.

Early elections

In 1974 and 1976, Newt Gingrich made two unsuccessful runs for Congress in Georgia's sixth congressional district, which stretched from the southern Atlanta suburbs to the Alabama border. Gingrich lost both times to incumbent Democrat Jack Flynt.

Jack Flynt was a conservative Democrat of the Georgia delegation who had family political ties that bound him to a particular powerbase within his district. He had served in Congress since 1955 and never faced a serious challenge prior to Gingrich's two runs against him. In both cases, Flynt just barely squeaked by even though 1974 and 1976 were generally considered bad years for Republicans due to the Watergate scandal. Flynt's struggle, which was emblematic of the struggle of many southern Democrats to hold onto political power, is documented in Richard Fenno's Congress at the Grassroots.

Flynt chose not to run for re-election in 1978, and the Democrats fielded state senator Virginia Shapard in his place. Shapard's support of the Equal Rights Amendment [1] backfired against her in the socially conservative district, and Gingrich defeated her by eight points.

United States Representative

Gingrich was reelected ten times, facing only one truly difficult race. This difficult race was during the House elections of 1990 when he barely defeated Democrat David Worley.

Pre-speakership congressional activities

In 1981, Gingrich co-founded the Congressional Military Reform Caucus as well as the Congressional Space Caucus. In 1983 he founded the Conservative Opportunity Society, a group that included young conservative House Republicans. In 1983, Gingrich demanded the expulsion of fellow representatives Dan Crane and Gerry Studds for their roles in the Congressional Page sex scandal.

In May 1988, Gingrich (along with 77 other House members and the nonpartisan good government group Common Cause) brought ethics charges against Democratic Speaker of the House Jim Wright, who was alleged to have used a book deal to circumvent campaign finance laws and House ethics rules and eventually resigned as a result of the inquiry. Gingrich's success in forcing Wright's resignation was in part responsible for his rising influence in the Republican caucus. In 1989, after House Minority Whip Dick Cheney was appointed Secretary of Defense, Gingrich was elected to succeed him. Gingrich and others in the house, especially the newly-minted Gang of Seven, railed against what they saw as ethical lapses in the House, an institution that had been under Democratic control for almost 40 years. The House banking scandal and Congressional Post Office Scandal were emblems of this alleged corruption.

In his memoir "Man of the House", long time Democratic House Speaker Thomas "Tip" O'Neill took note of Gingrich, characterizing him as having a spark of genius and a passion for politics, but an erratic nature.

Election of 1992

During the 1990s round of redistricting, Democrats in the Georgia state legislature tried to draw Gingrich's district out from under him by splitting most of his old territory among two other districts. Gingrich's home in Carrollton was drawn into the 3rd District, represented by five-term Democrat Richard Ray.

At the same time, they created a new 6th district located in Fulton and Cobb counties in the wealthy northern suburbs of Atlanta—an area that Gingrich had never represented. However, the plan backfired when Gingrich sold his home in Carrollton, moved to Marietta in the new 6th and won a very close Republican primary. His opponent, a local politician, used Gingrich's carpetbagger status and the recent House bank scandal against him, and almost pulled an upset. The primary victory was tantamount to election in the new, heavily Republican district. Also, Ray narrowly lost to Republican state senator Mac Collins.

Speaker of the House

The Contract with America and rise to Speaker

In the 1994 campaign season, in an effort to offer a concrete alternative to shifting Democratic policies and to unite distant wings of the Republican Party, Gingrich presented Richard Armey's and his Contract with America, a list of campaign promises given as intended acts of Congress, and based in part on Ronald Reagan's 1985 state of the union address. The contract was signed by himself and other Republican candidates for the House of Representatives. The contract ranged from issues with broad popular support, including welfare reform, term limits, tougher crime laws, and a balanced budget law, to more specialized legislation such as restrictions on American military participation in United Nations missions. In the November elections of 1994, Republicans gained 54 seats and took control of the House for the first time since 1954. thumb Longtime House Minority Leader Bob Michel of Illinois had not run for reelection in 1994, giving Gingrich, as the highest-ranking Republican returning to Congress, the inside track to becoming Speaker. The Congress fulfilled Gingrich's Contract, voting on all ten of the Contract's issues within the first 100 days of the session. Legislation proposed by the 104th Congress included term limits for Congressional Representatives, tax cuts, welfare reform, and a balanced budget law, as well as independent auditing of the finances of the House of Representatives and elimination of non-essential services such as the House barbershop and shoe shine concessions. While many of the major proposals of the Contract did not become law or were substantially weakened, they represented a dramatic departure change from the legislative goals and priorities of previous Congresses.

The Contract was criticized by the liberal Sierra Club and by the leftist labor magazine Mother Jones as a Trojan horse tactic which, while deploying the rhetoric of reform, would have the real effect of allowing corporate polluters to profit at the expense of the environment;[5] it was also accused of being designed to make the rich richer at the expense of the poor and middle class.[6] It was referred to by opponents, including President Clinton, as the "Contract on America" (where a "contract on" somebody is an agreement to have them killed).

Susan Smith

In 1994 Gingrich claimed that Susan Smith's murder of her two children was a sign of the evils caused by Democrats "I think that the mother killing the two children in South Carolina vividly reminds every American how sick the society is getting and how much we need to change things.... The only way you get change is to vote Republican."[2]

Government shutdown and the Air Force One "snub"

The momentum of the Republican Revolution stalled in late 1995 and early 1996 as a result of a budget fight between Congressional Republicans and President Bill Clinton. Without enough votes to override President Clinton's veto, Gingrich led the Republicans not to submit a revised budget, allowing the previously-approved appropriations to expire on schedule, and causing parts of the Federal government to shut down for lack of funds.

Gingrich inflicted a temporary blow to his public image by suggesting that the Republican hard-line stance over the budget was in part due to his feeling "snubbed" by the President the day before, after being forced to leave Air Force One via the back door during his return from Yitzhak Rabin's funeral in Israel. Gingrich was lampooned in the media as a petulant figure with an inflated self-image, and editorial cartoons depicted him as having thrown a temper tantrum. Democratic leaders took the opportunity to attack Gingrich's motives for the budget stand-off, and the shutdown ultimately contributed to Clinton's re-election in November of that year.[7][8]

Ethics charges

Gingrich was accused of hypocrisy and unethical behavior when he accepted a $4.5 million advance as part of a book deal, in light of his previous role in the investigation of Jim Wright. Following the accusations, Gingrich returned the advance.

Including charges related to the book deal, Democrats filed 84 ethics charges against Speaker Gingrich during his term, including claiming tax-exempt status for a college course run for political purposes and using the GOPAC political action committee as a slush fund. All charges were eventually dropped following an investigation by the Republican-led House Ethics Committee. However, Gingrich admitted to "unintentionally" giving inaccurate information to the House Ethics Committee during the course of the investigation. The committee did not indict him on charges of intentional perjury.[9] The matter was settled when he agreed to reimburse the Committee $300,000 for the cost of prolonging the investigation. The payment was described as a "cost assessment" and not a fine by the Committee.[10] He also agreed to not "spin" the story in the media, but admit publicly to his transgressions.

On January 10, 1997, the New York Times printed a story that revealed Gingrich, in collusion with other House Republicans, planned to abrogate his agreement by misrepresenting the ethics violations he committed. The story was supported by quotes from a taped phone conversation between Gingrich and his fellow Republicans. A firestorm of controversy ensued, with Republicans insisting that the privacy of the participants in the conversation has been breached, and others insisting that the public has a need to know about Gingrich's intent to violate his agreement with the Ethics Committee. The couple who taped the conversation, John and Alice Martin, who claimed that they "lucked" into it over their police scanner while driving in their car and who "just happened" to have a recorder available, pled guilty to charges surrounding the taping and paid a $500 fine. Five years later, Democratic representative Jim McDermott publicly admitted that he leaked the tape. Republican John Boehner, one of the participants in the conversation, sued McDermott for $10,000 in civil damages; as of May 2006, that court case is in the US Court of Appeals in Washington, possibly heading for the Supreme Court. Many media organizations and watchdog groups support McDermott for political reasons; claiming that if Boehner prevails, the ability of news organizations to reveal embarrassing and potentially criminal behavior of government officials will be drastically curtailed.[11].

Coup attempt of 1997

In the summer of 1997, a few House Republicans had come to see Gingrich's public image as a liability and attempted to replace him as Speaker. According to Joe Scarborough of Florida, a member of the Republican freshman class of 1994, the coup attempt resulted from a view that Gingrich's public notoriety was becoming a drag on party efforts. House Majority Leader Dick Armey started his efforts in 1997 by whispering to so-called "rebels" tired of Gingrich's leadership. Armey and other Republican leaders started approaching these rebels after the July 4th break in 1997.

Twenty-four House Republicans met on the night of July 10th in South Carolina congressman Lindsey Graham's office in an attempt to vacate the Speaker's chair. A simple majority was needed to oust Gingrich; when Democrats' votes were included with those of the dissident Republicans, he would have had to step aside. However, due to a last-minute disagreement between Armey and Tom Coburn over whether Bill Paxon or Armey should become the new speaker, Armey informed Gingrich that his position as Speaker was at risk. Gingrich and the House leadership quickly and successfully moved to restore order within the party, and Paxon didn't run for reelection in 1998. However, the incident would prove a precursor of Gingrich's future prospects as Speaker.

Fall from speakership, resignation from the House

By 1998, Gingrich had become a highly visible and polarizing figure in the public's eye, making him an easy target for Democratic congressional candidates across the nation. In 1997 a strong majority of Americans believed Gingrich should have been replaced as Speaker of the House, and he held an all-time low job approval rating of 28%.[12] During this period, Gingrich was at the forefront of Republican calls for the investigation and impeachment of Bill Clinton for commiting perjury by lying under oath during the Lewinsky scandal[citation needed], and he focused on the perjury charges as a unifying campaign theme in national Republican advertising. Republicans claimed that the focus was not the tryst itself, but perjurious statements made by the Mr. Clinton in connection with the Lewinsky tryst. Democratic candidates in races across the country targeted Gingrich specifically during the campaign season. Commentator David Horowitz estimated that 80,000 television spots ran over the course of the election season on Gingrich. The Democratic efforts would ultimately prove successful, although it was Republican insiders who forced Gingrich to resign.

The Republicans expected big gains from the 1998 Congressional elections. In fact, Gingrich predicted a 30-seat Republican pickup. Instead, the Republicans lost five seats, the poorest results in 34 years for any party not in control of the White House. Having led the GOP to focus on the impeachment project as a principal strategy, Gingrich took most of the blame for the defeat. Amid threats of a rebellion in his caucus, he announced on November 6 that he would not only stand down as Speaker, but would leave the House as well. He had been elected to an 11th term in that election, but declined to take his seat.

Gingrich's role as master GOP strategist ended with his stepping down as Speaker and resignation from the House, but his legacy in politics remains today.

Legacy in politics and language

A major part of Gingrich's legacy as a politician has been in achieving the effective use of language and the news media to further political goals.

Gingrich took the chair of the Republican political action committee GOPAC in 1986 and transformed it into an effective vehicle for electing conservative candidates to office. This was accomplished in significant part by establishing and promoting a consistent language and theme for use by Republicans at all electoral levels. This theme, in Gingrich's own words, was that of "a conservative opportunity society replacing the liberal welfare state", emphasizing "workfare over welfare" and promoting the idea that "we are the majority". GOPAC training tapes containing advice on "Newtspeak" were sent out to rising GOP political candidates throughout the country.

Similarly, GOPAC distributed a memo to freshman Republican House members. Entitled "Language: A Key Mechanism of Control," it listed a number of "optimistic positive governing words" that candidates could use when campaigning in order to "speak like Newt," (movement, opportunity, passionate, e.g.) and a parallel list of contrasting words, such as "bureaucracy, cheat, coercion, etc.," which it advised the candidate to apply to their "opponent, their record, proposals and their party."[13][14]

At the start of the Republican Revolution, Gingrich and GOPAC's efforts had succeeded in dictating the theme of national political debate at the time.

Post-congressional life

Gingrich has since remained involved in national politics and public policy debate. He is a senior fellow at the conservative think tank American Enterprise Institute, focusing on health care (he has founded the Center for Health Transformation), information technology, the military, and politics. He sometimes serves as a commentator, guest or panel member on television news shows. He is listed as a contributor by Fox News Channel, and frequently appears as a guest on the channel; he has also hosted occasional specials for the FNC.

Possible 2008 presidential run

Since the release of Winning the Future: A 21st Century Contract with America in January 2005, Gingrich has been mentioned as a potential Presidential candidate for the 2008 U.S. presidential election. He has made several trips to Iowa and New Hampshire to discuss his book and on April 1, 2005, David Yepsen wrote in the Des Moines Register that Gingrich was "setting a high standard for what other GOP candidates need to be talking about - and doing - if they want to win here."[citation needed] Gingrich has voiced criticism against the Republican Party, and has argued that the party must adapt if it is to remain a dominant force in US politics.

In 2005, Newt Gingrich and his wife Callista established the Newt L. and Callista L. Gingrich Scholarship for instrumental music majors at Luther College in Decorah, Iowa. (Gingrich's wife is a Luther alumna.)[15]

In May 2005, he raised eyebrows when he announced that he was collaborating with Hillary Clinton on a new health-care bill.[16][17] Some analysts speculated such a move was a calculated attempt to project a more "moderate" front on the part of both politicians, in anticipation of a potential 2008 run.

On October 13, 2005, Gingrich suggested he's actually considering a run for president, saying "There are circumstances where I will run", elaborating that those circumstances would be if no other candidate champions some of the platform ideas advocated by Gingrich.[3]

In March 2006, Gingrich began a regular series of daily radio commentaries, titled "Winning the Future", the same as his recent book. These commentaries are modeled after Ronald Reagan's radio addresses in the mid-1970s.

On April 10, 2006 Gingrich was quoted in an Argus Leader article titled "Newt: Pull out of Iraq" as saying "It was an enormous mistake for us to try to occupy that country after June of 2003...We have to pull back, and we have to recognize it." The headline of the article later changed to "Gingrich at USD: Scale back to small force in Iraq."[18] On April 11th, Gingrich clarified his statement by posting an audio clip and transcript of the Iraq portion of the speech in question on his website.[19] According to the transcript, he believes the strategy used by the CPA after June 2003 was a mistake and that America needs to turn over control to Iraqis as rapidly as possible.

On April 29, 2006, supporters launch http://www.draftnewt.org to form a grassroots movement to support a possible Gingrich run for the Presidency.

On June 2, 2006, the Minnesota Republican Party at their state convention held a straw poll for the GOP nomination in 2008.[citation needed] Gingrich came in first place at 40%, with the next highest in the straw poll of GOP delegates being Senator George Allen at 15%.

Books authored

Nonfiction

- The Government's Role in Solving Societal Problems. Associated Faculty Press, Incorporated. January 1982 ISBN 0-86733-026-0

- Window of Opportunity. Tom Doherty Associates, December 1985. ISBN 0-312-93923-X

- Contract with America (co-editor). Times Books, December 1994. ISBN 0-8129-2586-6

- Restoring the Dream. Times Books, May 1995. ISBN 0-8129-2666-8

- Quotations from Speaker Newt. Workman Publishing Company, Inc., July 1995. ISBN 0-7611-0092-X

- To Renew America. Farrar Straus & Giroux, July 1996. ISBN 0-06-109539-7

- Lessons Learned The Hard Way. HarperCollins Publishers, May 1998 ISBN 0-06-019106-6

- Presidential Determination Regarding Certification of the Thirty-Two Major Illicit Narcotics Producing and Transit Countries. DIANE Publishing Company, September 1999. ISBN 0-7881-3186-9

- Saving Lives and Saving Money. Alexis de Tocqueville Institution, April 2003. ISBN 0-9705485-4-0

- Winning the Future. Regnery Publishing, January 2005. ISBN 0-89526-042-5

- Rediscovering God in America: Reflections on the Role of Faith in Our Nation's History and Future. Integrity Publishers, October 2006. ISBN 1591454824

Alternative history collaboration with William R. Forstchen

In 1995, he collaborated with William R. Forstchen on the alternate history novel 1945, describing a 1945 where the US fought against (and defeated) Japan only, Nazi Germany defeated the Soviet Union and the two confront each other in a cold war which swiftly turns hot.

The book drew many negative reviews which Gingrich supporters claimed were biased and politically-motivated (see [4]). Among other things it was described as being "a disguised tract against gun control", as the key scene depicts an armed Tennessee civilian militia, led by Alvin York, defeating Otto Scorzeny's commandos who raid Oak Ridge. It ended with a cliffhanger - Rommel invading Scotland and the British facing a desperate fight - but a promised sequel, provisionally called "Fortress Europa", was never written.

Instead, Gingrich and Forstchen turned to co-authoring an alternative history of the Civil War. The trilogy consists of Gettysburg: A Novel of the Civil War, Grant Comes East, and Never Call Retreat: Lee and Grant - The Final Victory.

References

- ^ Eilperin, Juliet (2006-06-10). "Gingrich May Run in 2008 if No Frontrunner Emerges". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2006-08-25.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Good Newt, Bad Newt". Vanity Fair (via PBS).

- ^ "Gingrich vs. Gingrich". Salon.

- ^ Lemann, Nicholas (1996-02-26). "America's New Class System". CNN/Time. Retrieved 2006-08-12.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Contract on America's Environment". The Planet Newsletter. Sierra Club. Retrieved 2006-08-15.

- ^ Garrett, Major (March/April 1995). "Beyond the Contract". Mother Jones. Retrieved 2006-08-15.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Hollman, Kwame (1996-11-20). PBS.org "The State of Newt". PBS. Retrieved 2006-08-14.

{{cite news}}: Check|url=value (help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Murdock, Deroy (2000-08-28). NationalReview.com "Newt Gingrich's Implosion". National Review. Retrieved 2006-08-15.

{{cite news}}: Check|url=value (help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Farnsworth, Elizabeth (1996-12-23). "EMBATTLED LEADER". PBS. Retrieved 2006-08-15.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Yang, John E. and Dewar, Helen (1997-01-18). washingtonpost.com "Ethics Panel Supports Reprimand of Gingrich". Washington Post. p. A01. Retrieved 2006-08-15.

{{cite news}}: Check|url=value (help); Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sanders, Eli (May 18 - May 24, 2006). thestranger.com "The War on Jim McDermott". The Stranger. Retrieved 2006-08-15.

{{cite news}}: Check|url=value (help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Holland, Keating (1997-04-18). "Poll: Majority Says Gingrich Loan 'Inappropriate'". CNN. Retrieved 2006-08-15.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Language: A Key Mechanism of Control". Retrieved 2006-08-12.

- ^ "Gingrich-izing Public Broadcasting". The Nation. 2005-09-27. Retrieved 2006-08-15.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Gingrich Foundation establishes scholarship fund at Luther College". Decorah Newspapers. Retrieved 2006-08-15.

- ^ "Gingrich, Clinton Collaborate on Health Care Bill". Associated Press. 2005-05-11. p. A04. Retrieved 2006-08-15.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ showmenews.com "Gingrich, Clinton join forces". Knight Ridder. 2005-05-13. Retrieved 2006-08-15.

{{cite news}}: Check|url=value (help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ LaBelle, Monica (2006-04-11). "Gingrich at USD: Scale back to small force in Iraq (video)". Argus Leader. Retrieved 2006-08-15.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Newt on Iraq at the University of South Dakota". Newt.org. 2006-04-11. Retrieved 2006-08-15.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)

- Books

-

- Fenno Jr., Richard F. (2000). Congress at the Grassroots: Representational Change in the South, 1970-1998. UNC Press. ISBN 0-8078-4855-7.

- Journals

-

- Little, Thomas H. (1998). "On the Coattails of a Contract: RNC Activities and Republicans Gains in the 1994 State Legislative Elections". Political Research Quarterly. 51 (1): 173–190.

- Web

-

- "GINGRICH, Newton Leroy - Biographical Information". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved February 4.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "Titles List". Library of Congress Online Catalog. Retrieved December 5.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "The War on Jim McDermott".

- "GINGRICH, Newton Leroy - Biographical Information". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved February 4.

External links

- The Center for Health Transformation

- A 1984 expose in Mother Jones magazine detailed the earliest days of Gingrich's political career.

- Winning the Future A weekly column by Newt Gingrich from Human Events

- Draft Newt '08 Unofficial site advocating a Gingrich for President in 2008 campaign.

- RightWeb profile of Newt Gingrich

- SourceWatch profile of Newt Gingrich

- Contemporary comments on Gingrich's resignation as Speaker

- Article on Newt's resignation.

- Gingrich's comments on the Air Force One "snub" and the budget

- PBS Frontline Documentary on Gingrich, including GOPAC details.

- Profile: Newt Gingrich, Center for Cooperative Research.

- Profile: Newt Gingrich, Notable Names Database

- Rotten bio: Newt Gingrich

- Senior Fellow at AEI, The American Enterprise Institute

- Newt Gingrich's 1996 GOPAC memo

- Kurt Nimmo. The War According to Newt Gingrich, CounterPunch, December 10, 2003.

- Newt Gingrich. Defeat of terror, not roadmap diplomacy, Middle East Quarterly, Summer 2005.

- Gingrich argues people expect corruption from Democrats, not GOP, MediaMatters.org, January 4, 2006.

- Newt Gingrich files, MediaMatters

- Newt Gingrich files, Media Transparency

- Newt Gingrich files, DailyKos.

- Newt Gingrich interview on the Tavis Smiley show

- Newt Gingrich interview on space policy by the Space Review

- 1943 births

- Living people

- American adoptees

- American Enterprise Institute

- Baptists

- Members of the United States House of Representatives from Georgia

- People from Harrisburg, Pennsylvania

- People from McLean, Virginia

- Speakers of the United States House of Representatives

- Time magazine Persons of the Year

- Tulane University alumni

- American conservatives

- American Christians

- Congressional scandals