J. Robert Oppenheimer

J. Robert Oppenheimer (April 22, 1904–February 18, 1967) was a Jewish-American physicist and the scientific director of the Manhattan Project, the World War II effort to develop the first nuclear weapons, at the secret Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico. Known colloquially as "the father of the atomic bomb," Oppenheimer lamented the weapon's killing power after it was used to destroy the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. After the war, he was a chief advisor to the newly-created Atomic Energy Commission and used that position to lobby for international control of atomic energy and to avert the nuclear arms race with the Soviet Union. After invoking the ire of many politicians and scientists with his outspoken political opinions during the Red Scare, he had his security clearance revoked in a much-publicized and politicized hearing in 1954. Though stripped of his political influence, Oppenheimer continued to lecture, write, and work in physics. A decade later, President Lyndon B. Johnson awarded him the Enrico Fermi Award as a gesture of rehabilitation.

Early life

Oppenheimer was born in New York in 1904 to Julius (a wealthy textile-importer who had immigrated to the United States from Germany in 1888) and Ella Friedman Oppenheimer (an artist). He studied at the Ethical Culture Society School where, in addition to mathematics and science, he was exposed to a variety of subjects ranging from Greek to French literature. Throughout his life, he remained a versatile scholar, proficient in science as well as the humanities. He entered Harvard University one year late due to an attack of colitis. During the interim, he went with a former English teacher to recuperate in New Mexico, where he fell in love with horseback riding and the mountains and plateaus of the Southwest. He returned reinvigorated and made up for the delay by graduating in just three years with a major in chemistry.

While at Harvard, Oppenheimer was introduced to experimental physics during a course on thermodynamics taught by Percy Bridgman, and was encouraged to go to Europe for future study, as a world-class education in the subject could not then be obtained in the United States. He was accepted for postgraduate work at Ernest Rutherford's famed Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge, working under the emminent but aging J.J. Thomson. Oppenheimer's clumsiness in the laboratory made it apparent that his forte was theoretical, not experimental, physics, so he left in 1926 for the University of Göttingen to study under Max Born. Göttigen was one of the top centers for theoretical physics in Europe, and Oppenheimer made a number of friends who would go on to great success, such as Paul Dirac, before he obtained his Ph.D. at the age of 22.

At Göttingen, Oppenheimer published many important contributions to the then newly developed quantum theory. In September 1927, he returned to Harvard as a National Research Council Fellow, and in early 1928 he studied at the California Institute of Technology. Here he received numerous invitations for teaching positions, and accepted an assistant professorship in physics at the University of California, Berkeley. In his words, "it was a desert," yet paradoxically a fertile place of opportunity. He maintained a joint appointment with Caltech, where he spent every spring term in order to avoid isolation. Before his Berkeley professorship began, he was diagnosed with a mild case of tuberculosis, and with his brother Frank, spent some weeks at a ranch in New Mexico, "Perro Caliente," which he leased and eventually purchased. He recovered, and returned to Berkeley, where he prospered as an advisor and collaborator to a generation of physicists who admired him for his intellectual virtuosity and broad interests. He also worked closely with (and became good friends with) experimental physicist Ernest O. Lawrence and his cyclotron pioneers.

Oppenheimer became credited with being a founding father of the American school of theoretical physics, and developed a reputation for his eclecticism, his interest in languages and Eastern philosophy, and the eloquence and clarity with which he thought. But he was also troubled throughout his life, and professed to experiencing periods of depression so profound that only hard work was a "palliative." A tall, thin chain smoker who often neglected to eat during periods of intellectual discomfort and concentration, Oppenheimer was marked by many of his friends as having a tendency to self-destruct, and during numerous periods of his life worried his colleagues and associates with his melancholy and insecurity. He developed numerous affectations, seemingly in an attempt to convince those around him—or possibly himself—of his self-worth. He was said to be mesmerizing, hypnotic in private interaction but often frigid in more public settings. His associates fell into two camps: one which saw him as an aloof and impressive genius; another which saw him as pretentious and insecure. His students almost always fell into the former category, adopting "Oppie's" affectations, from his way of walking to talking and beyond.

Oppenheimer did important research in astrophysics, nuclear physics, and spectroscopy. His most well-known contribution, made as a graduate student, is the Born-Oppenheimer approximation, important for the quantum theory of atoms and molecules. He also made important contributions to the theory of cosmic ray showers, and work which led eventually toward descriptions of quantum tunneling. In the late 1930s, he was the first to write papers suggesting the existence of what we today call black holes. Even in the immensely abstruse topics he was expert in, his papers were considered difficult to understand. Oppenheimer was very fond of using elegant, if extremely complex (and sometimes incorrect), mathematical techniques to demonstrate physical principles.

During the 1920s, he kept himself aloof of worldly matters, and claimed to have not learned of the stock market crash of 1929 until some time after the fact (Oppenheimer himself had little worry regarding financial matters, as his family ties provided him with ample funding). It was not until he became involved with Jean Tatlock, the daughter of a Berkeley literature professor, in 1936, that he showed any interest in politics. Like many young intellectuals in the 1930s he became a supporter of Communist ideas, and having much more money than most professors (he inherited over $300,000, a massive sum at the time, after his father's death in 1937) was able to bankroll many left-wing efforts. The majority of his radical work included things like hosting fund-raisers for the Republican cause in the Spanish Civil War, and other anti-Fascist activity, and he never openly joined the Communist Party (his brother Frank, however, did, against the Robert's advice). In November 1940 he married Katherine Puening Harrison, a radical Berkeley student, and by May 1941 they had their first child, Peter.

The Manhattan Project

When World War II started, Oppenheimer eagerly became involved in the efforts to develop an atomic bomb which were already taking up much of the time and facilities of Lawrence's Radiation Laboratory at Berkeley. In 1941, Lawrence, Vannevar Bush, Arthur Compton, and James Conant were trying to wrest the bomb project from the Uranium Committee established by President Roosevelt in 1939, because they felt it was proceeding too slowly. Oppenheimer was invited to take over work on neutron calculations, a task which he threw himself into with full vigor, renouncing what he called his "left-wing wanderings" to abandon himself to his responsibilities (though many of his friends and students were still quite radical). When the U.S. Army was given jurisdiction over the bomb effort, now called the Manhattan Project, project director General Leslie R. Groves (who had just finished directing the construction of the Pentagon) appointed Oppenheimer as its scientific director, to the surprise of many. Groves knew of Oppenheimer's potential security problems, but thought that Oppenheimer was the best man to direct a diverse team of scientists and would be unaffected by his past political leanings.

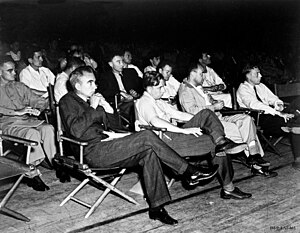

One of Oppenheimer's first acts was to host a summer school for bomb theory at his building in Berkeley. The mix of European physicists and his own students—a group including Robert Serber, Emil Konopinski, Felix Bloch, Hans Bethe, and Edward Teller—busied themselves calculating what needed to be done, and in what order, to make the bomb. At the time, research for the project was going on at many different universities and laboratories across the country, presenting a problem for both security and cohesion. Oppenheimer and Groves decided that they needed a centralized, secret research laboratory. Scouting for a site, Oppenheimer was drawn to New Mexico, not far from his ranch. On a flat mesa near Santa Fe, the Los Alamos laboratory was hastily built, a rag-tag collection of barracks and mud. There Oppenheimer collected a group of the most brilliant physicists of his day, including Enrico Fermi, Richard Feynman, Robert R. Wilson, and Victor Weisskopf, as well as Bethe and Teller. His wife gave birth there to their second child, Katherine (called Toni), in 1944.

Oppenheimer was noted for his mastery of all scientific aspects of the project and for his efforts to control the inevitable cultural conflicts between scientists and the military. He was an iconic figure to his fellow scientists, as much a figurehead of what they were working towards as a scientific director. All the while he was under investigation by both the FBI and the Manhattan Project's internal security arm for his past left-wing associations. During interviews regarding an incident in which he was solicited for nuclear secrets by Communist sympathizers, Oppenheimer often gave contradictory and equivocating statements. Project leader Groves still thought Oppenheimer too important to oust him over this suspicious behavior.

The joint work of the scientists at Los Alamos resulted in the first nuclear explosion at Alamogordo on July 16, 1945, which Oppenheimer named "Trinity," possibly after a John Donne verse, in honor of his old girlfriend Tatlock, who had committed suicide some months before. Oppenheimer later recalled that while witnessing the explosion he thought of a verse from the Hindu book, the Bhagavad Gita: "I am become death, the destroyer of worlds." According to his brother, at the time he simply exclaimed, "It worked." News of the successful test was rushed to President Harry S. Truman, who could use it as leverage at the upcoming Potsdam Conference on the fate of post-war Europe.

Though the initial impetus for the development of the bomb—a perceived arms race with Nazi Germany—had been shown unnecessary (when the German program was discovered to be stillborn by the Manhattan Project's ALSOS investigation), Oppenheimer and his scientists pressed on. To some physicists, including Teller and Leo Szilard, using the weapon on a civilian area would be a moral travesty. A petition was circulated at the labs in Los Alamos and Oak Ridge pleading that use of the bomb against civilians would be immoral and unnecessary. Oppenheimer opposed the petition and warned Szilard and Teller not to impede the project.

The scientist-administrators were divided on whether and how to use the now-tested weapon. Lawrence initially favored not using the weapon on a live target, arguing that a demonstration alone would be enough to convince the Japanese government of the futility of continuing the war. Oppenheimer and many of the military advisors strongly disagreed with this assessment. Oppenheimer feared that if it were announced where such a demonstration might occur, the enemy might move American POWs or other human shields into the region. It is uncertain how much stock the American government and military put in the opinions of the scientists on the weapon they had created.

On August 6, 1945, the "Little Boy" uranium bomb was dropped on the city of Hiroshima, Japan. Three days later, the Fat Man "plutonium" bomb was dropped on Nagasaki. Hundreds of thousands of civilians were killed immediately, and many more would die as a result over time.

The pride which Oppenheimer had felt after the successful "Trinity" test was soon replaced by guilt and horror, though he never said that he regretted making the weapon. During his only visit to postwar Japan in 1960, he was asked by reporter whether he felt any guilt on developing the bomb. Oppenheimer quipped, "It's not that I don't feel bad about it. It's just that I don't feel worse today than what I felt yesterday."

Postwar activities

Overnight, Oppenheimer became a national spokesman for science, and an emblem of a new type technocratic power. Nuclear physics became a powerful force as all governments of the world began to realize the strategic and political power which came with nuclear weapons and their horrific implications. Like many scientists of his generation, he felt that the only security from atomic bombs would come from some form of transnational organization (such as the newly formed United Nations) which could institute some sort of program to stifle a nuclear arms race.

After the Atomic Energy Commission was created in 1946 as a civilian agency in control of nuclear research and weapons issues, Oppenheimer was immediately appointed as the Chairman of its General Advisory Committee (GAC), and left the directorship of Los Alamos. From this position he was able to give policy advice on a number of nuclear-related issues, including project funding, laboratory construction, and even international policy—though the GAC's advice was not always implemented. The important Baruch Plan of 1946, which called for the internationalization of atomic energy, was derived in part from his opinions, though to his dismay included many additional provisions which made it clear that the goal of the plan was simply to prevent the USSR from gaining its own bomb, rather than a lasting international decision. The plan was not surprisingly rejected by the USSR without fanfare, and it became clear to Oppenheimer that an arms race was unavoidable due to the mutual distrust of the U.S. and the USSR.

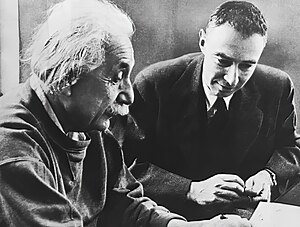

In 1947, he left Berkeley, citing difficulties with the administration during the war, and took up the directorship of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton Township, New Jersey, and would later hold Albert Einstein's old position of senior professor of theoretical physics (this association with Einstein annoyed Oppenheimer in his later years, as he felt overshadowed by the legacy of the famous physicist).

While still Chairman of the GAC, Oppenheimer lobbied vigorously for international arms control, funding for basic science, and attempted to influence policy away from a heated arms race. When the issue was raised of whether a Manhattan Project-style crash program to develop an atomic weapon based on nuclear fusion—the hydrogen bomb—should be pursued, Oppenheimer initially recommended against it, though he had been in favor of developing such a weapon in the early days of the Manhattan Project. Partly he was motivated by ethical concerns: such a weapon could only be used strategically against civilian targets and would result in millions of deaths if ever implemented. Partly, though, it was practical: at the time, there was no design of such a weapon which seemed promising, and Oppenheimer felt that resources would be better spent creating a large force of fission weapons. He was eventually overridden by President Harry Truman, who announced a crash program after the Soviet Union tested their first atomic bomb in 1949. Oppenheimer and his fellow GAC members who had recommended against the program, especially James Conant, felt personally shunned and considered retiring from the committee. In the end, they stayed on, though their views on the hydrogen bomb were well known. Oppenheimer changed his opinion, however, after the 1951 development of the Teller-Ulam design for such a bomb, which seemed workable and made the development of the weapon by both sides, in Oppenheimer's eyes, inevitable. The first hydrogen bomb, "Ivy Mike", was tested in 1952.

In his role as a political advisor, Oppenheimer made numerous enemies. The FBI under J. Edgar Hoover had been following his activities since before the war, when he had numerous Communist sympathies as a young, radical professor, and was more than willing to furnish incriminating evidence about past Communist ties to Oppenheimer's political enemies, such as Lewis Strauss, an AEC commissioner who had long harbored resentment against Oppenheimer both for his activity in opposing the development of the hydrogen bomb and for his humiliation of Strauss before congress some years earlier. Strauss and Senator Brien McMahon, author of the 1946 Atomic Energy Act, pushed President Eisenhower to revoke Oppenheimer's security clearance. This came following a number of large controversies about whether some of Oppenheimer's students, including David Bohm, Joseph Weinberg, and Philip Morrison, had been Communists at the time they had worked with Oppenheimer at Berkeley. Oppenheimer's brother, Frank Oppenheimer, was forced to testify in front of the infamous House Un-American Activities Committee, where he admitted that he had been a member of the Communist Party in the 1930s, but refused to name other members. He was subsequently fired from his university position, could not find a further job in physics, and became a cattle rancher in Colorado for the next decade.

In 1953, Oppenheimer was accused of being a security risk and was asked to resign by Eisenhower. Oppenheimer refused and requested a hearing to assess his loyalty, and in the meantime his security hearing was suspended. The much-publicized public hearing which followed focused heavily on Oppenheimer's past Communist ties and his behavior during the Manhattan Project with suspected disloyal or Communist scientists. Edward Teller, with whom Oppenheimer had at one time disagreed on whether the more powerful hydrogen bomb should be developed, notably testified against Oppenheimer at the hearing, an act which led to much outrage by the scientific community and resulted in Teller's virtual expulsion from academic science. Many top scientists, as well as government and military figures, testified on Oppenheimer's behalf. Inconsistencies in his testimony and his erratic behavior on the stand convinced some that he was unreliable and a possible security risk. Oppenheimer's clearance was revoked.

During his hearing, Oppenheimer testified willingly on the left-wing behavior of many of his scientific colleagues. It has been speculated by historians (in particular Richard Polenberg) that had Oppenheimer not had his clearing stripped at the hearing (it would have expired in a matter of days anyhow), he would be remembered as someone who had "named names", pointing his finger at former friends in a desperate attempt to save his own reputation. As it happened, though, Oppenheimer was seen by most of the scientific community as a martyr to McCarthyism, an eclectic liberal who was unjustly attacked by warmongering enemies, symbolic of the shift of scientific creativity from the realm academic university and into the firm grip of the military.

Stripped of his political power, Oppenheimer continued to lecture, write, and work on physics. He toured Europe, and even Japan, giving talks about the history of science, the role of science in society, and the nature of the universe. In 1963, at the urging of many of Oppenheimer's political friends who had recently ascended to power, President John F. Kennedy awarded Oppenheimer the Enrico Fermi Award as a gesture of political rehabilitation. A little over a week after Kennedy's assassination, his successor, President Lyndon Johnson, presented Oppenheimer with the award, officially "for contributions to theoretical physics as a teacher and originator of ideas, and for leadership of the Los Alamos Laboratory and the atomic energy program during critical years". Accepting the award, Oppenheimer told Johnson: "I think it is just possible, Mr. President, that it has taken some charity and some courage for you to make this award today. That would seem a good augury for all our futures". It was, however, only symbolic in its effects, as Oppenheimer still lacked the vital security clearance and could have no effect on official policy.

In his final years, Oppenheimer continued his work at the Institute for Advanced Study, and worked to bring together intellectuals from a variety of disciplines who he felt to be at the height of their powers to solve the most pertinent questions of the current age. His lectures in America, Europe and Canada were published in a number of books. But he largely felt that the effort had failed to make any serious progress on actual policy.

Robert Oppenheimer died of throat cancer in 1967. His funeral was attended by many of the scientists, politicians, and military men who had been in his life. His ashes were spread over the Virgin Islands, a summer retreat of his family.

Legacy

Robert Oppenheimer's life has been culturally and historically understood as indicative of a number of broader trends in the transformation of science from the 1920s through the 1950s.

As a scientist, Oppenheimer is remembered by his students and colleagues as being a brilliant and engaging teacher, the founder of the American school of theoretical physics. This has occasionally brought up the question as to why Oppenheimer never himself won a Nobel Prize, and the usual answer given by scholars is that his scientific attentions would often change quite rapidly. As such, he never worked long enough on any one scientific topic to create significant headway or deserving of the Nobel Prize. His lack of a Prize would not be odd—most scientists do not win Nobel Prizes—had not so many of his associates (Fermi, Bethe, Lawrence, Dirac, Feynman, etc.) won them. Some scientists and historians have speculated that, out of all of his work, his investigations towards black holes may have warranted a Prize had he lived long enough to see them brought into fruition by later astrophysicists.

As an advisor, Oppenheimer has served to delineate a shift in the interactions between science and the military. During World War II, scientists became directly involved in organized military research to an unprecedented degree (some research of this sort had occurred during World War I, but it was far smaller in scope). Because of the threat Fascism seemed to pose for the survival of Western civilization, scientists volunteered in great numbers both for technological and organizational assistance to the Allied effort, and the product of such endeavors included such powerful tools as radar, the proximity fuse, and operations research, among other things. As a cultured, intellectual, theoretical physicist who became a disciplined military organizer, Oppenheimer represented the shift away from the idea that scientists had their "head in the clouds" and that knowledge on such previously esoteric subjects as the composition of the atomic nucleus had no "real-world" applications. When Oppenheimer was ultimately ejected from his ability to influence the use of his creations in 1954, he also came to symbolize the folly that scientists could control how others would use their work and research. The shift was also well illustrated by his replacement as director of Los Alamos, Norris Bradbury, a former military man of a quite different stripe from the Sanskrit reading scholar who preceded him. In this sense, Oppenheimer has come to symbolize the dilemmas involved in figuring out the moral responsibility of the scientist in the years since the 1940s.

Most popular depictions of Oppenheimer, notably German playwrite Heinar Kipphardt's 1968 play on his trial, portray his security struggles as a confrontation between right-wing militarists (symbolized by Edward Teller) and left-wing intellectuals (symbolized by Oppenheimer) over the moral question of weapons of mass destruction. In their own works, historians have often contested this as an over-simplification: the trial against Oppenheimer, while very political, was undertaken as much for personal reasons as much for any explicit political agenda, and Oppenheimer's opinion on nuclear weapons was often too inconsistent to brand him as a pacifist in any sense. An example of this often pointed to is Oppenheimer's stance on the construction of the hydrogen bomb: popular moralizations often depict Oppenheimer as being against the bomb for moral reasons. A more complete look shows Oppenheimer to have been against the bomb primarily for technical reasons, and once the technical objections had been satisfied, Oppenheimer in fact supported the construction of the bomb on the grounds that it was inevitable that the Soviet Union would too construct one.

In another example, despite his apparently remoseful attitudes—claiming that physicists "had known sin"—Oppenheimer was one of the more vocal supporters of using the first atomic weapons on "built up areas" in the days before the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. And rather than being a consistent force against the "Red-baiting" of the late-1940s and early-1950s, he had in fact testified against many of his former colleagues and students, both before his hearing and during it. In one incident which caused a slight falling out between him and Hans Bethe, Oppenheimer had testified in a particularly damning manner towards about his former student Philip Morrison which was selectively leaked to the press shortly afterwards. Historians have interpretted this as an attempt by Oppenheimer to please his colleagues in the government (and to perhaps avert attention to his own previous left-wing ties), but in the end it became a liability: under cross-examination at his security hearing in 1954, it became clear that if Oppenheimer had really thought Morrison to be as much a Communist liability as he had previously testified, then his action in recommending him to the Manhattan Project seemed reckless or at the very least contradictory.

The eventual removal of his security clearance was also probably as much related to his inconsistent testimony, and his open admission of telling lies to intelligence agents, as it did his left-wing views of the 1930s (shared by many intellectuals and scientists in the wake of the Great Depression and the rise of Fascism in Europe). Nevertheless, the trope of Oppenheimer as a martyr has proven to be indelible, and to speak of Oppenheimer has always been to speak of the limits of science and politics, however more complicated the actual history actually is. The portrayal of Oppenheimer as a modern day Faustus in the opera "Doctor Atomic" is a somewhat extreme expression of this point of view.

Notes

On Oppenheimer's first initial

The meaning of the "J" in J. Robert Oppenheimer has been the source of confusion among many. Historians Alice Kimball Smith and Charles Weiner sum it up best, in their volume Robert Oppenheimer: Letters and recollections (Harvard University Press: Cambridge, 1980), on page 1: "Whether the 'J' in Robert's name stood for Julius or, as Robert himself once said, 'for nothing' may never be fully resolved. His brother Frank surmises that the 'J' was symbolic, a gesture in the direction of naming the eldest son after the father but at the same time a signal that his parents did not want Robert to be a 'junior.'" In Peter Goodchild's J. Robert Oppenheimer: Shatterer of Worlds (Houghton Mifflin: Boston, 1981), it is said that Robert's father, Julius, added the empty initial to give Robert's name additional distinction, but Goodchild's book has no footnotes so the source of this assertion is unclear. Robert's claim that the J. stood "for nothing" is taken from an autobiographical interview conducted by Thomas S. Kuhn on November 18, 1963, which currently resides in the Archive for the History of Quantum Physics. When investigating Oppenheimer in the 1930s and 1940s, the FBI itself was befuddled by the "J," deciding erroneously that it probably stood for Julius or, strangely, Jerome.

See also

External links

- Biography and online exhibit created for the centennial of his birth

- Biographical Memoirs: Robert Oppenheimer by Hans Bethe

References

- David C. Cassidy, J. Robert Oppenheimer and the American Century (New York: Pi Press, 2005). ISBN 0131479962

- Gregg Herken, Brotherhood of the Bomb: The Tangled Lives and Loyalties of Robert Oppenheimer, Ernest Lawrence, and Edward Teller (New York: Henry Holt and Co., 2002). ISBN 0805065881

- Richard Polenberg, ed., In the Matter of J. Robert Oppenheimer: The Security Clearance Hearing (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2002). ISBN 0801437830

- S.S. Schweber, In the Shadow of the Bomb: Oppenheimer, Bethe, and the Moral Responsibility of the Scientist, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000). ISBN 0691049890

- Alice Kimball Smith and Charles Weiner, Robert Oppenheimer: Letters and Recollections, (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1980).

- U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, In the Matter of J. Robert Oppenheimer (Washington, D.C.: 1954).

- Herbert York, The Advisors: Oppenheimer, Teller, and the Superbomb (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1976).

Works by Oppenheimer

- Science and the Common Understanding (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1954).

- The Open Mind (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1955).

- The flying trapeze: Three crises for physicists (London: Oxford University Press, 1964).

- Uncommon sense (Cambridge, MA: Birkhäuser Boston, 1984). (posthumorous)

- Atom and void: Essays on science and community (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989). (posthumorous)

Hans Bethe's "Biographical Memoirs" also contains a full list of Oppenheimer's scientific publications.