Aladdin Sane

| Aladdin Sane | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | 13 April 1973 | |||

| Recorded | 6 October 1972, 4–11 December 1972, c. 18–24 January 1973[1] | |||

| Studio | Trident, London; RCA, New York City | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 40:47 | |||

| Label | RCA | |||

| Producer |

| |||

| David Bowie chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Aladdin Sane | ||||

| ||||

Aladdin Sane is the sixth studio album by English singer-songwriter David Bowie, released on 13 April 1973 by RCA Records. The follow-up to his breakthrough The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, it was the first album he wrote and released from a position of stardom. It was produced by Bowie and Ken Scott and features contributions from Bowie's backing band the Spiders from Mars – comprising Mick Ronson, Trevor Bolder and Mick Woodmansey – as well as pianist Mike Garson, two saxophonists and three backing vocalists. It was recorded at Trident Studios in London and RCA Studios in New York City between legs of the Ziggy Stardust Tour.

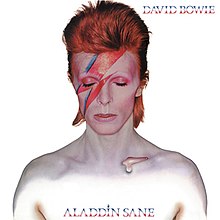

Bowie wrote most of the tracks on the road in the US between shows. Because of this, many of the tracks are greatly influenced by America and Bowie's perceptions of the country. Due to the American influence and the fast-paced songwriting, the album features a tougher and raunchier glam rock sound than its predecessor. The lyrics reflect the pros of Bowie's newfound stardom and the cons of touring, and paint pictures of urban decay, drugs, sex, violence and death. Some of the songs are influenced by the English rock band the Rolling Stones, and a cover of their song "Let's Spend the Night Together" is included. The album features a new character called Aladdin Sane, a pun on "A Lad Insane", whom Bowie described as "Ziggy Stardust goes to America". The album cover, shot by Brian Duffy and featuring a lightning bolt across Bowie's face, was the most expensive cover ever made at the time and represents the split personality of the Aladdin Sane character and Bowie's mixed feelings of the tour and stardom. It is regarded as one of his most iconic images.

Preceded by the singles "The Jean Genie" and "Drive-In Saturday", Aladdin Sane was Bowie's most commercially successful record up to that point, peaking at No. 1 on the UK Albums Chart and No. 17 on the US Billboard 200. The album also received positive reviews from music critics and, although many found it to be inferior to its predecessor, it is been regarded by Bowie biographers as one of his essential albums. It has also been classified as one of the greatest albums of all time by Rolling Stone and NME and one of the best albums of the 1970s by Pitchfork. The album has been reissued several times and was remastered in 2013 for its 40th anniversary, which was included on the box set Five Years (1969–1973) in 2015.

Background and writing

Following the release of his album The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars and his performance of "Starman" on the BBC television programme Top of the Pops in early July 1972, Bowie was launched to stardom.[2][3] The television performance helped propel the album to No. 5 on the UK Albums Chart and it remained on the chart for two years, although the album was not as big a success in the US as in the UK, peaking at only No. 75 on the Billboard 200.[4] With the album, Bowie became one of the most important glam rock artists.[4][5] To promote the album, Bowie undertook the Ziggy Stardust Tour in both the UK and the US, the latter ultimately becoming a major influence for his next album.[6][7][8]

Aladdin Sane was my idea of rock and roll America. Here I was on this great tour circuit, not enjoying it very much. So inevitably my writing reflected that, this kind of schizophrenia that I was going through. Wanting to be up on stage performing my songs, but on the other hand not really wanting to be on those buses with all those strange people. Being basically a quiet person, it was hard to come to terms. So Aladdin Sane was split down the middle.[8]

– David Bowie on the theme of the album

Aladdin Sane was the first album Bowie wrote and released from a position of stardom.[9] He composed most of the tracks on the road during the US tour in late 1972.[10] Because of this, many of the tracks were influenced by America, and his perceptions of the country.[11] Biographer Christopher Sandford believes the album showed that Bowie "was simultaneously appalled and fixated by America".[7] The tour also took a toll on Bowie's mental health, which further influenced his writing; it marked the beginning of his longtime cocaine addiction.[12] He co-produced Lou Reed's album Transformer and the Stooges' album Raw Power the same year, adding to his exhaustion.[13][14] His mixed feelings about the journey stemmed, in Bowie's words, from "wanting to be up on the stage performing my songs, but on the other hand not really wanting to be on those buses with all those strange people ... So Aladdin Sane was split down the middle."[8] Bowie would later say that due to being on the road, he was unsure of the direction to take for the album. While he felt that he had said as much as he wanted to say about Ziggy Stardust, he knew he'd "end up doing...'Ziggy Part 2'".[10] He stated: "There was a point in '73 where I knew it was all over. I didn't want to be trapped in this Ziggy character all my life. And I guess what I was doing on Aladdin Sane, I was trying to move into the next area – but using a rather pale imitation of Ziggy as a secondary device. In my mind, it was Ziggy Goes to Washington: Ziggy under the influence of America."[14]

Rather than continue the Ziggy Stardust character directly, Bowie decided he would create a new persona, Aladdin Sane.[15] The character reflected the theme of "Ziggy goes to America"[16][17] and, according to Bowie, was less defined and "clear cut" than Ziggy Stardust, and "pretty ephemeral".[18] According to biographer David Buckley, the character was a "schizoid amalgamation" that was reflected in the music.[19]

Recording

Aladdin Sane was mainly recorded between December 1972 and January 1973, between legs of the Ziggy Stardust Tour.[15] Like his previous two albums, it was co-produced by Bowie and Ken Scott and featured Bowie's backing band the Spiders from Mars – comprising Mick Ronson, Trevor Bolder and Mick Woodmansey.[15][20] Also in the lineup for the album was American pianist Mike Garson, who was suggested to Bowie by RCA executive Ken Glancey[21] as well as singer-songwriter Annette Peacock, after she declined to play the synthesiser on Aladdin Sane; Garson had played on her recent I'm the One album.[6][22] Garson played the opening chords of "Changes" to Bowie and Ronson and was hired on the spot.[6][21] The pianist came from a jazz and blues background, which Pegg believes veered the album from pure rock 'n' roll and expanded Bowie's experimental horizons.[8] Buckley called Aladdin Sane the beginning of Bowie's "experimental phase" and cited Garson's presence on the album as "revolutionary".[22] Scott noted that Garson added elements to the arrangements that were not there before, including more keyboards and synthesisers. Garson later said that Scott as producer "got the best piano sound out of any of his performances for Bowie."[23] Garson remembered being given a lot of attention from Bowie in the studio, who mainly wanted to see what Garson could do.[8] The piano Garson played on the album was the same one used by Rick Wakeman for Hunky Dory.[24] He remained with Bowie's entourage for the next three years.[22] Along with Garson, others added to the tour and album's lineup included saxophonists Ken Fordham and Brian "Bux" Wilshaw and backing vocalists Juanita Franklin, Linda Lewis and longtime friend Geoffrey MacCormack (later known as Warren Peace); MacCormack would subsequently appear on numerous records by Bowie throughout the remainder of the 1970s.[25]

The first song recorded for the album was "The Jean Genie", on 6 October 1972 at RCA Studios in New York City; it was mixed at RCA Studios in Nashville a week later. According to Bolder, the song was recorded rather quickly, in about 90 minutes and in only one take, other than a few overdubs. According to Cann and O'Leary, Bowie produced the session himself.[26][27] After the session, the band and crew left New York to continue the tour in Chicago.[26] Bowie's manager Tony Defries originally wanted to enlist American producer Phil Spector to produce the album, but after receiving no response from Spector, Bowie invited Scott back to co-produce.[15] Two months later on 9 December, the band reconvened in New York with Scott and recorded "Drive-In Saturday" and "All the Young Dudes"; the latter Bowie wrote for the English rock band Mott the Hoople.[28][29] The American tour concluded later that month, after which the band returned overseas to perform a series of Christmas concerts in England and Scotland. Following these concerts, the band regrouped at Trident Studios in London on 19 January 1973 to record the remainder of the album.[30][31] On this day, the band recorded "1984", which, while left off Aladdin Sane, became an important track thematically for Bowie's 1974 album Diamond Dogs.[30][32] The following day, the band recorded the backing tracks for "Panic in Detroit", the title track and the "sax version" of "John, I'm Only Dancing".[30][33] A provisional running order was compiled the same day, including "John, I'm Only Dancing" and an unknown track titled "Zion". While Pegg doubts the existence of this track, as it is not registered with any of Bowie's music publishers,[34] Cann writes that Rykodisc considered it for inclusion on the 1990 reissue of Aladdin Sane but Bowie rejected it.[30] Vocals were added to "Panic in Detroit" and the title track four days later, marking the end of the sessions.[30] Although Cann does not have recording dates for the rest of the album's tracks,[35] Doggett and O'Leary conclude that the remaining songs were recorded at the Trident sessions in January.[36][37]

Music and lyrics

We wanted to take it that much rougher. Ziggy was rock and roll but polished rock and roll. [Bowie] wanted certain tracks to go like the Rolling Stones and unpolished rock and roll.[8]

– Ken Scott on the album's sound

Like its predecessor Ziggy Stardust, Aladdin Sane is a glam rock album,[4][38][20] with elements of hard rock.[39] Aladdin Sane's American influence and the album's fast-paced development helped add a tougher, rawer and edgier rock sound.[7][8][19] Some of the songs, including "Watch That Man", "Drive-In Saturday" and "Lady Grinning Soul" are influenced by the English rock band the Rolling Stones; a cover of their song "Let's Spend the Night Together" is included.[8] Each track was ascribed a location on the album label to indicate where it was written or took its inspiration:[40][41] New York ("Watch That Man"), "Seattle–Phoenix ("Drive-In Saturday"), Detroit ("Panic in Detroit"), Los Angeles ("Cracked Actor"), New Orleans ("Time"), Detroit and New York again ("The Jean Genie"), RHMS Ellinis, the vessel that had carried Bowie home in December 1972 ("Aladdin Sane"), London ("Lady Grinning Soul") and Gloucester Road ("The Prettiest Star").[9][17][42] According to Pegg, the lyrics of Aladdin Sane paint pictures of urban decay, degenerate lives, drug addiction, violence and death.[17] Pegg further notes some of the themes presented on Bowie's previous works are reflected in Aladdin Sane: "notions of religion shattered by science, extraterrestrial encounters posing as messianic visitations, the impact on society of different kinds of 'star', and the degradation of human life in a spiritual void."[11] Classic Rock Review writes that the music reflects the pros of newfound stardom and the cons of the perils of touring.[43]

Side one

The album opener, "Watch That Man", was written by Bowie in response to seeing two concerts by the American rock band New York Dolls. According to Doggett, the Dolls' first two albums were important in representing the American response to the British glam rock movement.[44][45] Bowie was impressed with their sound and wanted to emulate it on a song.[46] "Watch That Man" is described by Pegg as "a sleazy garage rocker" heavily influenced by the Rolling Stones, specifically their song "Brown Sugar".[47] The mix, in which Bowie's lead vocal is buried beneath the instrumental sections, has been heavily criticised by critics and fans.[47][48][49] Pegg and Doggett describe the mix as reminiscent of the Stones' Exile on Main St..[46][47] According to O'Leary, this was Scott's doing; the producer said the track "just seemed to have more power that way".[50] The label and Bowie's publisher MainMan initially requested a new mix with Bowie's vocal more upfront, but after Bowie and Scott complied, it was deemed inferior to the original mix.[50][51]

The title track "Aladdin Sane (1913–1938–197?)", often shortened to just "Aladdin Sane", was inspired by Evelyn Waugh's 1930 novel Vile Bodies,[52][53] which Bowie read during his trip on the RHMS Ellinis back to the UK.[54] The dates in parentheses refer to the years preceding World War I and World War II, the third unknown date reflecting Bowie's belief in an impending World War III.[55][56] Described by biographer David Buckley as the album's "pivotal" song, it saw Bowie exploring more experimental genres, rather than strict rock 'n' roll.[22] It features a piano solo by Garson[39] that is described by Pegg as the track's "defining feature".[55] Garson had originally attempted a blues solo and Latin solo, which were politely rejected by Bowie, who asked him to play something more akin to the avant-garde jazz genre that Garson had come from. Improvised and recorded in one take, the solo is described by Buckley as a "landmark" recording.[57] Doggett similarly believes that the track's landscape belongs to Garson.[58] The coda features a quote from the song "On Broadway".[55][59]

"Drive-In Saturday" is described by Pegg as "arguably the finest track" on the album.[60] It was written by Bowie following an overnight train ride between Seattle and Phoenix in early November 1972. He witnessed a row of silver domes in the distance and assumed they were secret government facilities used for a post-nuclear fallout. The radiation has affected people's minds and bodies to the point that they need to watch films in order to learn to have sex again.[60][61][9] A glam rock song,[62] it is heavily influenced by 1950s doo-wop music.[9][60][63] The track name-checks Mick Jagger, the model Twiggy, and psychologist Carl Jung.[64] Bowie also acknowledges Marc Bolan, quoting the T. Rex song "Get It On", and the New York Dolls' guitarist Sylvain Sylvain.[60][64] Bowie originally offered it to Mott the Hoople as the follow-up single to "All the Young Dudes" but they rejected it in favour of "Honaloochie Boogie".[65][66]

"Panic in Detroit" was inspired by Iggy Pop's stories of the Detroit riots in 1967 and the rise of the White Panther Party, specifically their leader John Sinclair.[67][68] Bowie compared the ideas of Sinclair to the rebel martyr Che Guevara for the narrator in "Panic in Detroit".[69] The lyrics are very dark, featuring images of urban decay, violence, drugs, emotional isolation and suicide.[70] Doggett finds a thematic link between the song and Bob Dylan's "All Along the Watchtower", which "used a similar three-chord riff to underpin its apocalypse".[71] O'Leary compares the song to "Five Years", stating that it makes the latter "seem like a genteel middle-class apocalypse."[72] Musically, the song itself is built around a Bo Diddley beat;[9] Pegg considers Ronson's guitar part very "bluesy".[70] Woody Woodmansey originally refused to play the Diddley drum beat requested by Bowie and Ronson, saying it was "too obvious". He instead opted for a simpler tom-tom rhythm with phased cymbals, while Geoff MacCormack played the beat Bowie requested on congas and maracas.[70][72] The track also features backing vocals from Juanita Franklin and Linda Lewis, which, together with the band, O'Leary describes as "sounding like a collective murder".[73]

"Cracked Actor" was written by Bowie following his stay at Sunset Boulevard in Los Angeles, where he witnessed prostitutes, drug use and sex. The song's narrator is an aging film star whose life is beginning to decline; he is "stiff on his legend" and encounters a prostitute, whom he despises.[74][75] There are numerous puns regarding film stardom and sex: "show me you're real/reel", "smack, baby, smack" and "you've made a bad connection".[75][76] Doggett describes the song as predominantly hard rock, with only a hint of glam,[74] while Pegg describes Ronson's guitar as "dirty blues".[76] It features Bowie on harmonica but Garson does not perform on the track.[73] "Cracked Actor" was performed frequently on the 1974 Diamond Dogs Tour, where it was turned into what Buckley calls a "sleazy, sax driven epic";[77] Bowie sang to a skull and donned a "Shakespearean doublet" while performing it.[76]

Side two

"Time" was originally written by Bowie as "We Should Be On By Now" for his friend George Underwood, with vastly different lyrics.[78][79] According to Pegg, a demo featuring Underwood, Bowie and Ronson was recorded in mid-1971 around the same time as Underwood's demo of "Song for Bob Dylan". The song was then rewritten, influenced by the death of New York Dolls drummer Billy Murcia and the concepts of relativity and mortality.[80][81][51] One line about looking at a clock is taken from Chuck Berry's 1958 song "Reelin' and Rockin'".[78] The song's use of the word "wanking" led to it being banned by the BBC from radio stations; Bowie altered the word to "swanking" for NBC's The 1980 Floor Show.[80] Garson's piano, described by Pegg and O'Leary as stride[82][83] and by Doggett as Brechtian cabaret-style,[78] dominates the track while Ronson plays a similar line on guitar, at one point quoting "Ode to Joy" from Beethoven's Ninth symphony.[84][85][54] Bowie's voice is fitted with a "lingering echo delay", which Doggett considers as representing time "in action".[78] The middle section features Bowie's heavy breathing, which was brought to the forefront in the mix by Scott.[22][82]

"The Prettiest Star" was originally recorded by Bowie in 1970 as the follow-up single to "Space Oddity".[86][87] It was written for his first wife Angela Barnett, whom he married shortly after the original's release.[88][89] The original was produced by Tony Visconti and featured Marc Bolan on guitar, with whom Bowie would spend the next few years as a rival for the crown of the king of glam rock. Despite positive reviews, the original recording flopped.[90] The subsequent rerecording on Aladdin Sane was glam-influenced, and featured Bolan's guitar part mimicked almost note-for-note by Ronson.[91] Buckley calls the rerecording a "revamped and much improved" version.[92] Doggett argues that the song's appeared out of place on Aladdin Sane,[93] while Pegg finds that the references to "screen starlets" and "the movies in the past" mesh with its other nostalgic references.[94] O'Leary is puzzled that Bowie decided to remake "The Prettiest Star", but agrees with Pegg that the lyrics fit certain themes of other tracks. He compares the original to the remake as a "valentine" to a "rowdy engagement party".[95]

"Let's Spend the Night Together" is the only cover song on the album. Written by Mick Jagger and Keith Richards and recorded by the Rolling Stones in 1967, the song's appearance blatantly acknowledges the influence of the Stones on the entire album.[96] While the original was psychedelic, Bowie's rendition is faster, raunchier and more glam-influenced.[97] It features synthesisers that Pegg believes gives the track a "fresh, futuristic sheen". Several critics also consider it a gay appropriation of a heterosexual song.[96][97] The cover has been criticised in ensuing decades as camp and unsatisfying.[97][98]

"The Jean Genie" was the first song written and recorded for the album. It began as an impromptu jam titled "Bussin'" on the charter bus when travelling between Cleveland and Memphis.[99][100] The guitar riff is Bo Diddley-inspired and is a variation of the Yardbirds' "I'm a Man" and, according to Doggett, "Smokestack Lightning".[12][100] The song is described by Jon Savage of The Guardian as glam rock,[101] by Douglas Wolk of Pitchfork as blues rock,[102] and by Dave Thompson of AllMusic as hard rock.[103] Bowie called it "a smorgasbord of imagined Americana" and his "first New York song", he wrote the lyrics to "entertain" Warhol associate Cyrinda Foxe, who appeared in the song's accompanied music video.[99][104] The lyrics were also an ode to Iggy Pop, Bowie calling the song's character a "white-trash, kind of trailer-park kid thing – the closet intellectual who wouldn’t want the world to know that he reads".[105][106] Carr and Murray write that the title has long been taken as an allusion to the author Jean Genet,[107] which Bowie confirmed in his 2005 book Moonage Daydream.[108]

"Lady Grinning Soul" was one of the final songs written for the album. It was also a last-minute addition, replacing the "sax version" of "John, I'm Only Dancing" as the closing track.[109] A possible inspiration for the song is American soul singer Claudia Lennear, who Bowie met during the US tour and also inspired the Rolling Stones' "Brown Sugar",[40][110][111] although O'Leary argues that the inspiration was French singer Amanda Lear, a sometime girlfriend of Bowie's.[112] Unlike other tracks on the album, the track has a sexual ambiance, lushness and serenity, and features flamenco-style guitar from Ronson and a Latin-style piano part from Garson.[22][110] The track has been described as a lost James Bond theme.[9][112]

Title and artwork

The name of the album is a pun on "A Lad Insane", which at one point was expected to be the title. When writing the album during the tour, it was under the working title Love Aladdin Vein, which Bowie said at the time felt right, but decided to change it partly due to its drug connotations.[25]

The album cover features a shirtless Bowie with red hair and a red-and-blue lightning bolt splitting his face in two while a teardrop runs down his collarbone.[25] It was shot in January 1973 by Brian Duffy in his north London studio.[25][40] Duffy would later photograph the sleeves for Lodger (1979) and Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps) (1980).[40] In an effort to ensure RCA promoted the album extensively, Tony Defries was determined to make the cover as costly as possible. He insisted on an unprecedented seven-colour system, rather than the usual four.[40][113] The image was the most expensive cover art ever made at the time.[18] The make-up designer for the shoot was artist Pierre Laroche, who remained Bowie's make-up artist for the remainder of the 1973 tour and the Pin Ups cover shoot.[113] Cann writes that Duffy and Laroche copied the lightning bolt from a National Panasonic rice-cooker in the studio. The make-up was completed with a "deathly purple wash", which Cann believes, together with Bowie's closed eyes, evoke a "death mask".[114] The final photo was selected from a group featuring Bowie looking directly at the camera. These photos later became a signature image of the V&A's David Bowie Is exhibition.[25][115] The shoot was the only time Bowie wore the design on his face, but it was later used for hanging backdrops at live performances.[40]

Duffy believed that Bowie's inspiration for the "flash" design came from a ring once worn by Elvis Presley; it featured the letters TCB (meaning Taking Care of Business) with a lightning flash.[40][25] Pegg believes the cover has a deeper meaning, representing the "split down the middle" personality of the Aladdin Sane character and reflecting Bowie's split feelings regarding the US tour and his newfound stardom.[116] The teardrop on his chest was Duffy's idea; Bowie said the photographer "just popped it in there. I thought it was rather sweet."[117][118] It was airbrushed by Philip Castle, who also helped create the silvery effect on Bowie's body on the sleeve; Castle previously created the poster for Stanley Kubrick's 1971 film A Clockwork Orange.[119] Regarded as one of the most iconic images of Bowie, it was called "the Mona Lisa of album covers" by Mick McCann of The Guardian.[115] Pegg calls it "perhaps the most celebrated image of Bowie's long career".[25] Upon release, the cover was polarising. According to Cann, some were offended and bewildered at Bowie's appearance, while others found it daring. In retrospect, Cann writes that a cover like Aladdin Sane's can be a risky move for artists whose success is relatively recent.[119]

Release

The lead single, "The Jean Genie", was released on 24 November 1972 by RCA.[120] In its advertising, the label stated: "Written in New York. Recorded in New York. Mixed in Nashville. The first single to come from Bowie's triumphant American tour."[120] The song charted at No. 2 on the UK Singles Chart, spending 13 weeks on the chart,[121] making it Bowie's biggest hit to date; it was kept off the top spot by Little Jimmy Osmond's "Long Haired Lover from Liverpool". The single fared worse in the US, peaking at No. 71 on the Billboard Hot 100.[122] It was promoted with a music video shot by Mick Rock, featuring bits of concert footage shot in San Francisco on 27 and 28 October 1972, interspersed with shots of Bowie posing around the Mars Hotel and actress Cyrinda Foxe.[122] The second single, "Drive-In Saturday", was released in the UK on 6 April 1973.[123] Like the previous single, it was a commercial success, peaking at No. 3 on the UK Singles Chart.[60] "Time" was later issued as a single in the US and Japan, and "Let's Spend the Night Together" in the US and Europe. In 1974, Lulu released a version of "Watch That Man" as the B-side to her single "The Man Who Sold the World", produced by Bowie and Ronson.[124]

Aladdin Sane was released on 13 April 1973 by RCA Records.[125][nb 1] With a purported 100,000 copies ordered in advance,[127] the album debuted at the top of the UK charts, where it remained for five weeks. In the US, where Bowie already had three albums in the charts, Aladdin Sane peaked at No. 17, making it Bowie's most successful album commercially in both countries to that date. According to Pegg, this feat was unheard of at the time and guaranteed Aladdin Sane's status as Britain's best-selling album since "the days of the Beatles".[113] The album is estimated to have sold 4.6 million copies worldwide, making it one of Bowie's highest-selling LPs.[128] The Guinness Book of British Hit Albums notes that Bowie "ruled the [British] album chart, accumulating an unprecedented 182 weeks on the list in 1973 with six different titles."[129] Following Bowie's death in 2016, the album reentered the US charts, peaking at No. 16 on the Billboard Top Pop Catalog Albums chart the week of 29 January 2016, where it remained for three weeks.[130] It also peaked at No. 6 on the Billboard Vinyl Albums the week of 18 March 2016, remaining on the chart for four weeks.[131]

Critical reception

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Blender | |

| Chicago Tribune | |

| Christgau's Record Guide | B+[134] |

| Encyclopedia of Popular Music | |

| Mojo | |

| Pitchfork | 9.0/10[102] |

| Q | |

| Rolling Stone | |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

Critical reaction to Aladdin Sane was generally laudatory, if more enthusiastic in the US than in the UK.[113] Ben Gerson of Rolling Stone remarked on "Bowie's provocative melodies, audacious lyrics, masterful arrangements (with Mick Ronson) and production (with Ken Scott)", and pronounced it "less manic than The Man Who Sold The World, and less intimate than Hunky Dory, with none of its attacks of self-doubt."[39] Billboard called it a combination of "raw energy with explosive rock".[113] In the British music press, letters columns accused Bowie of 'selling out' and Let It Rock magazine found the album to be more style than substance, considering that he had "nothing to say and everything to say it with".[113] The Village Voice critic Robert Christgau wrote a few years later that his favorite Bowie album had been Aladdin Sane, "the fragmented, rather second-hand collection of elegant hard rock songs (plus one Jacques Brel-style clinker) that fell between the Ziggy Stardust and Diamond Dogs concepts. That Bowie improved his music by imitating the Rolling Stones rather than by expressing himself is obviously a tribute to the Stones, but it also underlines how expedient Bowie's relationship to rock and roll has always been."[140]

Retrospectively, Aladdin Sane has received positive reviews from music critics and Bowie biographers but most reviewers have tended to unfavorably compare it to its predecessor. Stephen Thomas Erlewine of AllMusic believed that Aladdin Sane followed the same pattern as Ziggy Stardust, but for "both better and worse".[38] While praising the album for presenting unusual genres and being lyrically different, he criticised Bowie's cover of the Rolling Stones' "Let's Spend the Night Together", calling it "oddly clueless", and contended that "there's no distinctive sound or theme to make the album cohesive; it's Bowie riding the wake of Ziggy Stardust, which means there's a wealth of classic material here, but not enough focus to make the album itself a classic".[38] Douglas Wolk of Pitchfork also found the album similar to its predecessor, calling it "effectively Ziggy Stardust II, a harder-rocking if less original variation on the hit album".[102] He writes that while Ziggy Stardust ended with a "vision of outreach to the front row" in the lyrics of "Rock 'n' Roll Suicide", Aladdin Sane is "all alienation and self-conscious artifice, parodic gestures of intimacy directed to the theater balcony".[102] NME editors Roy Carr and Charles Shaar Murray called the album "oddly unsatisfying, considerably less than the sum of the parts".[9]

Legacy and reissues

It was almost like a treading-water album ... but funnily enough, in retrospect, for me it's the more successful album, because it's more informed about rock'n'roll than Ziggy was.[141]

– David Bowie discussing the album in the 1990s

Despite the massive commercial success of the album,[127] Pegg writes that when compared to its predecessor, Aladdin Sane feels more rushed.[141] Carr and Murray contend that "It was all too obvious that the heat was on... The songs were written too fast, recorded too fast and mixed too fast."[9] Spitz states that Bowie might have moved on from the Ziggy persona sooner had it not been for the pressure from his music publisher MainMan. Despite the album being critically viewed as inferior to its predecessor, Spitz calls it one of Bowie's classics and the songs "top-notch", and felt it ultimately showed that at the time Bowie was "still way ahead of the game".[142] Pegg calls it "one of the most urgent, compelling and essential of Bowie's albums".[141] Author Peter Doggett, comparing the album to Ziggy Stardust, describes Aladdin Sane as arguably a more "real" and "rewarding" album than its predecessor, with a "Stones-inspired, vivid production" outdoing the "somewhat flat sonic canvas" of Ziggy, but concludes that while Ziggy is more than the sum of its parts and has a long-lasting legacy, Aladdin Sane is "its songs, its sleeve, and nothing more".[143]

Bowie performed all the tracks, except "Lady Grinning Soul",[144] on his Ziggy Stardust Tour, and many of them on the Diamond Dogs Tour.[145] Live versions of all but "The Prettiest Star" and "Lady Grinning Soul" have been released on live albums including David Live (1974) and Ziggy Stardust: The Motion Picture (1983).[146][147] "The Jean Genie" is the only song on the album that Bowie played in concert throughout his career, exceptions being the 1995 Outside, the 1999 Hours and the 2002 Heathen Tour.[148] "Panic in Detroit" also appeared regularly in Bowie's later years; a remake of the song was recorded in 1979, intended for broadcast on ITV's The "Will Kenny Everett Make It to 1980?" Show but dropped in favour of the same session's acoustic remake of "Space Oddity", was released as a bonus track on the Rykodisc CD of Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps).[149][150][151]

The album has been reissued several times, initially being released on CD in 1984 by RCA.[152] In 1990, Dr. Toby Mountain at Northeastern Digital, Southborough, Massachusetts,[153] remastered Aladdin Sane from the original master tapes for Rykodisc, which released it with no bonus tracks.[154] It was again remastered in 1999 by Peter Mew at Abbey Road Studios for EMI and Virgin Records, and once more released with no bonus tracks.[155] In 2003, a 2-disc version was released by EMI/Virgin.[156] The second in a series of 30th Anniversary 2CD Edition sets (along with Ziggy Stardust and Diamond Dogs), this release includes a remastered version of the album on the first disc. The second disc contains ten tracks, a few of which had been previously released on the 1989 collection Sound + Vision.[157] A 40th anniversary edition, remastered by Ray Staff at London's AIR Studios, was released in CD and digital download formats in April 2013.[158] This 2013 remaster of the album was included in the 2015 box set Five Years 1969–1973 and rereleased separately, in 2015–2016, in CD, vinyl and digital formats.[159][160][161] A 12" limited edition of the 2013 remaster, pressed in silver vinyl, was released in 2018 to mark the 45th anniversary of the album.[162]

In 2003, Aladdin Sane was ranked among six Bowie entries on Rolling Stone's list of the 500 Greatest Albums of All Time (at No. 277), and No. 279 in a 2012 revised list.[163] It was later ranked No. 77 on Pitchfork's list of the top 100 albums of the 1970s.[164] In 2013, NME ranked the album 230th in their list of the 500 Greatest Albums of All Time.[165] The album was included in the 2006 edition of Robert Dimery's book 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die.[166] Based on Aladdin Sane's appearances in professional rankings and listings, the aggregate website Acclaimed Music lists it as 18th most acclaimed album of 1973, the 142nd most acclaimed album of the 1970s and the 499th most acclaimed album in history.[167]

Track listing

All tracks written by David Bowie, except where noted.[168]

- Side one

- "Watch That Man" – 4:30

- "Aladdin Sane (1913–1938–197?)" – 5:06

- "Drive-In Saturday" – 4:33

- "Panic in Detroit" – 4:25

- "Cracked Actor" – 3:01

- Side two

- "Time" – 5:15

- "The Prettiest Star" – 3:31

- "Let's Spend the Night Together" (Mick Jagger, Keith Richards) – 3:10

- "The Jean Genie" – 4:07

- "Lady Grinning Soul" – 3:54

- 2003 reissue bonus tracks[15]

- "John, I'm Only Dancing" ('Sax' version) – 2:45

- "The Jean Genie" (Single edit) – 4:07

- "Time" (Single edit) – 3:43

- "All the Young Dudes" (Mono mix) – 4:12

- "Changes" (Live at Boston Music Hall, 1 October 1972) – 3:20

- "The Supermen" (Live at Boston Music Hall, 1 October 1972) – 2:42

- "Life on Mars?" (Live at Boston Music Hall, 1 October 1972) – 3:25

- "John, I'm Only Dancing" (Live at Boston Music Hall, 1 October 1972) – 2:40

- "The Jean Genie" (Live at Santa Monica Civic Auditorium, 20 October 1972) – 4:10

- "Drive-In Saturday" (Live at Cleveland Public Auditorium, 25 November 1972) – 4:53

Personnel

Album credits per the Aladdin Sane liner notes and biographer Nicholas Pegg:[15][168]

- David Bowie – vocals, guitar, harmonica, saxophone, synthesiser, mellotron

- Mick Ronson – guitar, piano, vocals

- Trevor Bolder – bass guitar

- Mick "Woody" Woodmansey – drums

- Mike Garson – piano

- Ken Fordham – saxophone

- Brian "Bux" Wilshaw – saxophone, flutes

- Juanita "Honey" Franklin – backing vocals

- Linda Lewis – backing vocals

- G.A. MacCormack – backing vocals

- Production

- David Bowie – producer, arrangements

- Ken Scott – producer, engineer

- Mick Moran – engineer

- Mick Ronson – arrangements

Charts

Weekly charts

|

Year-end charts

|

Certifications

| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| France (SNEP)[183] | Gold | 100,000* |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[184] | Platinum | 300,000‡ |

| United States (RIAA)[185] | Gold | 500,000^ |

|

* Sales figures based on certification alone. | ||

Notes

References

- ^ Cann 2010, pp. 270, 277, 283.

- ^ Pegg 2016, p. 616.

- ^ Hepworth, David (15 January 2016). "How performing Starman on Top of the Pops sent Bowie into the stratosphere". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 15 April 2019. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ a b c Pegg 2016, p. 631.

- ^ Blum, Jordan (12 July 2012). "David Bowie: The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars". PopMatters. Archived from the original on 1 January 2017. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ^ a b c Cann 2010, p. 268.

- ^ a b c Sandford 1997, p. 109.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Pegg 2016, p. 634.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Carr & Murray 1981, pp. 52–56.

- ^ a b Buckley 2005, p. 157.

- ^ a b Pegg 2016, pp. 633–634.

- ^ a b Doggett 2012, p. 186.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "David Bowie – Biography & History". AllMusic. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- ^ a b Sheffield, Rob (13 April 2016). "How America Inspired David Bowie to Kill Ziggy Stardust With 'Aladdin Sane'". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 14 May 2020. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Pegg 2016, p. 632.

- ^ Buckley 2005, pp. 156–157.

- ^ a b c Pegg 2016, p. 633.

- ^ a b Doggett 2012, p. 203.

- ^ a b Buckley 2005, p. 156.

- ^ a b Gallucci, Michael (13 April 2018). "How David Bowie Returned, Ziggy-Like, for 'Aladdin Sane'". Ultimate Classic Rock. Archived from the original on 30 April 2020. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- ^ a b Pegg 2016, p. 948.

- ^ a b c d e f Buckley 2005, p. 160.

- ^ Buckley 2005, p. 161.

- ^ O'Leary 2015, p. 342.

- ^ a b c d e f g Pegg 2016, p. 635.

- ^ a b Cann 2010, p. 270.

- ^ O'Leary 2015, pp. 320–321.

- ^ Cann 2010, p. 277.

- ^ O'Leary 2015, pp. 309–312.

- ^ a b c d e Cann 2010, p. 283.

- ^ Pegg 2016, p. 951.

- ^ Pegg 2016, pp. 348–349.

- ^ Pegg 2016, p. 252.

- ^ Pegg 2016, p. 574.

- ^ Cann 2010, pp. 270, 282–283.

- ^ Doggett 2012, pp. 187–188, 192–195, 199–203.

- ^ O'Leary 2015, pp. 327, 333, 335, 344–346.

- ^ a b c d Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Aladdin Sane – David Bowie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 4 June 2012. Retrieved 10 July 2008.

- ^ a b c Gerson, Ben (19 July 1973). "Aladdin Sane". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 25 October 2012. Retrieved 21 March 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g Cann 2010, p. 294.

- ^ Spitz 2009, pp. 214–215.

- ^ Cann 2010, p. 292.

- ^ Albano, Ric (3 May 2018). "Aladdin Sane by David Bowie". Classic Rock Review. Archived from the original on 18 May 2020. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ^ Doggett 2012, pp. 187–188.

- ^ O'Leary 2015, p. 328.

- ^ a b Doggett 2012, p. 188.

- ^ a b c Pegg 2016, p. 532.

- ^ Carr & Murray 1981, p. 54.

- ^ Buckley 2005, p. 162.

- ^ a b O'Leary 2015, p. 329.

- ^ a b Cann 2010, p. 293.

- ^ Pegg 2016, p. 29.

- ^ Doggett 2012, p. 193.

- ^ a b O'Leary 2015, p. 339.

- ^ a b c Pegg 2016, p. 30.

- ^ O'Leary 2015, p. 341.

- ^ Buckley 2005, pp. 161–162.

- ^ Doggett 2012, p. 194.

- ^ O'Leary 2015, p. 343.

- ^ a b c d e Pegg 2016, p. 140.

- ^ O'Leary 2015, p. 325.

- ^ Pepinster, Catherine (16 August 1998). "Gold Dust: Glam rock's top 10 singles". The Independent. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

- ^ Barker, Emily (8 January 2018). "David Bowie's 40 greatest songs – as decided by NME and friends". NME. Archived from the original on 3 November 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2020.

- ^ a b Doggett 2012, p. 191.

- ^ O'Leary 2015, p. 326.

- ^ Pegg 2016, pp. 140–141.

- ^ Pegg 2016, pp. 363–364.

- ^ O'Leary 2015, pp. 330–331.

- ^ Doggett 2012, p. 189.

- ^ a b c Pegg 2016, p. 364.

- ^ Doggett 2012, pp. 189–190.

- ^ a b O'Leary 2015, p. 332.

- ^ a b O'Leary 2015, p. 333.

- ^ a b Doggett 2012, p. 201.

- ^ a b O'Leary 2015, p. 334.

- ^ a b c Pegg 2016, p. 115.

- ^ Buckley 2005, p. 202.

- ^ a b c d Doggett 2012, p. 192.

- ^ O'Leary 2015, p. 336.

- ^ a b Pegg 2016, p. 498.

- ^ Doggett 2012, pp. 192–193.

- ^ a b O'Leary 2015, p. 338.

- ^ Pegg 2016, p. 497.

- ^ Pegg 2016, pp. 497–498.

- ^ Buckley 2005, p. 159.

- ^ Pegg 2016, p. 373.

- ^ Buckley 2005, p. 67.

- ^ O'Leary 2015, p. 172.

- ^ Doggett 2012, pp. 82–83.

- ^ Pegg 2016, p. 374.

- ^ Carr & Murray 1981, p. 32.

- ^ Buckley 2005, p. 68.

- ^ Doggett 2012, p. 199.

- ^ Pegg 2016, p. 375.

- ^ O'Leary 2015, p. 174.

- ^ a b Pegg 2016, p. 282.

- ^ a b c O'Leary 2015, p. 346.

- ^ Doggett 2012, p. 200.

- ^ a b Pegg 2016, p. 245.

- ^ a b O'Leary 2015, p. 320.

- ^ Savage, Jon (1 February 2013). "The 20 best glam-rock songs of all time". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 August 2016. Retrieved 5 February 2016.

- ^ a b c d Wolk, Douglas (1 October 2015). "David Bowie: Five Years 1969–1973". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on 6 February 2016. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ^ Thompson, Dave. "The Jean Genie – David Bowie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 7 June 2019. Retrieved 8 February 2020.

- ^ Gordinier, Jeff (31 May 2002). "Loving the Aliens". Entertainment Weekly. No. 656. pp. 26–34.

- ^ Pegg 2016, pp. 245–246.

- ^ Buckley 2005, p. 158.

- ^ Carr & Murray 1981, p. 52.

- ^ Bowie & Rock 2005, pp. 140–146.

- ^ O'Leary 2015, pp. 347–348.

- ^ a b Pegg 2016, p. 261.

- ^ Doggett 2012, p. 202.

- ^ a b O'Leary 2015, p. 347.

- ^ a b c d e f Pegg 2016, p. 636.

- ^ Cann 2010, pp. 294–295.

- ^ a b McCann, Mick (7 May 2013). "David Bowie exhibition opens at Leeds' White Cloth Gallery". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 30 September 2015. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ^ Pegg 2016, pp. 634–635.

- ^ Loder, Kurt (23 April 1987). "Stardust Memories". Rolling Stone. No. 498. pp. 74–77, 80, 82, 168, 171.

- ^ Saul, Heather (25 March 2017). "David Bowie on the iconic lightning bolt from his Aladdin Sane cover". The Independent. Archived from the original on 20 August 2017. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ^ a b Cann 2010, p. 295.

- ^ a b Cann 2010, p. 276.

- ^ "1973 Top 40 Official UK Singles Archive – 13th January 1973". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- ^ a b Pegg 2016, p. 246.

- ^ Cann 2010, p. 289.

- ^ Pegg 2016, p. 317.

- ^ Cann 2010, p. 291.

- ^ "Aladdin Sane 45th anniversary silver vinyl due". David Bowie Official Website. Archived from the original on 16 February 2018. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- ^ a b Buckley 2005, p. 163.

- ^ Dee, Johnny (7 January 2012). "David Bowie: Infomania". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 8 January 2014. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ^ *Roberts, David (editor). The Guinness Book of British Hit Albums, p. 16. Guinness Publishing Ltd. 7th edition (1996). ISBN 0-85112-619-7

- ^ a b "David Bowie – Billboard". Billboard. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- ^ a b "David Bowie – Billboard". Billboard. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- ^ "David Bowie: Aladdin Sane". Blender. No. 48. June 2006. Archived from the original on 24 June 2007. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- ^ Kot, Greg (10 June 1990). "Bowie's Many Faces Are Profiled On Compact Disc". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 16 April 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (1981). "David Bowie: Aladdin Sane". Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies. Ticknor and Fields. ISBN 0-89919-026-X.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|titlelink=ignored (|title-link=suggested) (help) - ^ Larkin, Colin (2011). "Bowie, David". The Encyclopedia of Popular Music (5th concise ed.). Omnibus Press. p. 2795. ISBN 978-0-85712-595-8.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|titlelink=ignored (|title-link=suggested) (help) - ^ Buckley, David (May 2013). "David Bowie: Aladdin Sane". Mojo. No. 234. p. 102. ISSN 1351-0193.

- ^ O'Brien, Lucy (July 1999). "David Bowie: Aladdin Sane". Q. No. 154. p. 132.

- ^ Walters, Barry (10 July 2003). "David Bowie: Aladdin Sane". Rolling Stone. No. 926. p. 72.

- ^ Sheffield, Rob (2004). "David Bowie". In Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian (eds.). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide (4th ed.). Simon & Schuster. pp. 97–99. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|titlelink=ignored (|title-link=suggested) (help) - ^ Christgau, Robert (5 April 1976). "David Bowie Discovers Rock and Roll". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on 21 August 2017. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- ^ a b c Pegg 2016, p. 637.

- ^ Spitz 2009, p. 214.

- ^ Doggett 2012, p. 204.

- ^ O'Leary 2015, p. 349.

- ^ Pegg 2016, p. 1,142.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "David Live – David Bowie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 24 April 2019. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- ^ Viglione, Joe. "Ziggy Stardust: The Motion Picture – David Bowie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 24 April 2019. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- ^ Pegg 2016, p. 248.

- ^ O'Leary 2015, p. 330.

- ^ Pegg 2016, p. 365.

- ^ Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps) (CD liner notes). David Bowie. UK: Rykodisc. 1992. RCD 20147.

{{cite AV media notes}}: Unknown parameter|titlelink=ignored (|title-link=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ Aladdin Sane (CD liner notes). David Bowie. US: RCA Records. 1984. PCD1-4852.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ "Northeastern Digital home page". Archived from the original on 8 December 2007. Retrieved 26 May 2008.

- ^ Aladdin Sane (CD liner notes). David Bowie. US: Rykodisc. 1990. RCD 10135.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ Aladdin Sane (CD liner notes). David Bowie. US: EMI/Virgin Records. 1999. 7243 521902 0 1.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ Aladdin Sane (CD liner notes). David Bowie. US: EMI/Virgin. 2003. 7243 583012 2 9.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ Pegg 2016, pp. 873–875.

- ^ "40th anniversary remaster of Aladdin Sane due in April". David Bowie Official Website. Archived from the original on 13 January 2016. Retrieved 11 September 2015.

- ^ Five Years (1969–1973) (Box set liner notes). David Bowie. UK, Europe & US: Parlophone. 2015. DBXL 1.

{{cite AV media notes}}: Unknown parameter|titlelink=ignored (|title-link=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ "FIVE YEARS 1969 – 1973 box set due September". David Bowie Official Website. Archived from the original on 18 February 2016. Retrieved 16 February 2016.

- ^ Spanos, Brittany (23 June 2015). "David Bowie to Release Massive Box Set 'Five Years 1969–1973'". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 15 August 2020. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

{{cite magazine}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 16 August 2020 suggested (help) - ^ "Aladdin Sane 45th anniversary silver vinyl due". David Bowie Official Website. Archived from the original on 9 July 2018. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- ^ "500 Greatest Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. 31 May 2012. Archived from the original on 30 August 2019. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- ^ "The 100 Best Albums of the 1970s". Pitchfork. 23 June 2004. p. 3. Archived from the original on 11 April 2013. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ "The 500 Greatest Albums Of All Time: 300–201". NME. 25 October 2013. Archived from the original on 5 April 2019. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

- ^ Dimery, Robert, ed. (2006). 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die (revised and updated ed.). Universe Publishing. ISBN 0-7893-1371-5.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|titlelink=ignored (|title-link=suggested) (help) - ^ Franzon, Henrik. "Aladdin Sane". Acclaimed Music. Archived from the original on 19 September 2019. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 11 September 2019 suggested (help) - ^ a b Aladdin Sane (liner notes). David Bowie. UK: RCA Records. 1973. PK-2134.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ Kent, David (1993). Australian Chart Book 1970–1992. St Ives, NSW: Australian Chart Book. ISBN 0-646-11917-6.

- ^ "Top Albums/CDs – Volume 19, No. 20". RPM. 30 June 1973. Archived from the original (PHP) on 24 February 2014. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ^ "dutchcharts.nl David Bowie – Aladdin Sane". dutchcharts.nl. MegaCharts. Archived from the original (ASP) on 28 January 2013. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ^ "InfoDisc : Tous les Albums classés par Artiste > Choisir Un Artiste Dans la Liste" (in French). infodisc.fr. Archived from the original (PHP) on 7 November 2011. Retrieved 31 January 2014. Note: user must select 'David BOWIE' from drop-down.

- ^ Oricon Album Chart Book: Complete Edition 1970–2005. Roppongi, Tokyo: Oricon Entertainment. 2006. ISBN 4-87131-077-9.

- ^ "norwegiancharts.com David Bowie – Aladdin Sane". Archived from the original (ASP) on 16 October 2013. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ^ "Swedish Charts 1972–1975/Kvällstoppen – Listresultaten vecka för vecka > Maj 1973 > 15 Maj" (PDF). hitsallertijden.nl (in Swedish). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 May 2017. Retrieved 31 January 2014.Note: Kvällstoppen combined sales for albums and singles in the one chart; Aladdin Sane peaked at No. 9 on the list in the 2nd week of May 1973.

- ^ "Aladdin Sane – full Official Chart History". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- ^ "Aladdin Sane Chart History – Billboard". Billboard. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- ^ "Italiancharts.com – David Bowie – Aladdin Sane". Hung Medien. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- ^ "Ultratop.be – David Bowie – Aladdin Sane" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- ^ "Australiancharts.com – David Bowie – Aladdin Sane". Hung Medien. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- ^ "Les Albums (CD) de 1973 par InfoDisc" (in French). infodisc.fr. Archived from the original (PHP) on 27 October 2012. Retrieved 31 January 2013.

- ^ "The Official UK Charts Company : Album Chart History". Archived from the original on 17 December 2007. Retrieved 17 December 2007.

- ^ "Les Certifications depuis 1973: Albums". Infodisc.fr. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 3 January 2020. (select "David Bowie" from drop-down list)

- ^ "British album certifications – David Bowie – Aladdin Sane". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved 3 January 2019. Select albums in the Format field. Select Platinum in the Certification field. Type Aladdin Sane in the "Search BPI Awards" field and then press Enter.

- ^ "American album certifications – David Bowie – Aladdin Sane". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

Sources

- Bowie, David; Rock, Mick (2005). Moonage Daydream: The Life & Times of Ziggy Stardust. UK: Universe. ISBN 978-0-78931-350-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Buckley, David (2005) [1999]. Strange Fascination – David Bowie: The Definitive Story. London: Virgin Books. ISBN 978-0-75351-002-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cann, Kevin (2010). Any Day Now – David Bowie: The London Years: 1947–1974. Croyden, Surrey: Adelita. ISBN 978-0-95520-177-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Carr, Roy; Murray, Charles Shaar (1981). Bowie: An Illustrated Record. London: Eel Pie Publishing. ISBN 978-0-38077-966-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Doggett, Peter (2012). The Man Who Sold the World: David Bowie and the 1970s. New York, New York: HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 978-0-06-202466-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - O'Leary, Chris (2015). Rebel Rebel: All the Songs of David Bowie from '64 to '76. Winchester: Zero Books. ISBN 978-1-78099-244-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Pegg, Nicholas (2016). The Complete David Bowie (7th ed.). London: Titan Books. ISBN 978-1-78565-365-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sandford, Christopher (1997) [First published 1996]. Bowie: Loving the Alien. London: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80854-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Spitz, Marc (2009). Bowie: A Biography. New York, New York: Crown Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-71699-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)